User login

For MD-IQ use only

Regular vitamin D supplements may lower melanoma risk

. They also found a trend for benefit with occasional use.

The study, published in Melanoma Research, involved almost 500 individuals attending a dermatology clinic who reported on their use of vitamin D supplements.

Regular users had a significant 55% reduction in the odds of having a past or present melanoma diagnosis, while occasional use was associated with a nonsignificant 46% reduction. The reduction was similar for all skin cancer types.

However, senior author Ilkka T. Harvima, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio (Finland) University Hospital, warned there are limitations to the study.

Despite adjustment for several possible confounding factors, “it is still possible that some other, yet unidentified or untested, factors can still confound the present result,” he said.

Consequently, “the causal link between vitamin D and melanoma cannot be confirmed by the present results,” Dr. Harvima said in a statement.

Even if the link were to be proven, “the question about the optimal dose of oral vitamin D in order to for it to have beneficial effects remains to be answered,” he said.

“Until we know more, national intake recommendations should be followed.”

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers has been increasing steadily in Western populations, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals, the authors pointed out, and they attributed the rise to an increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

While ultraviolet radiation exposure is a well-known risk factor, “the other side of the coin is that public sun protection campaigns have led to alerts that insufficient sun exposure is a significant public health problem, resulting in insufficient vitamin D status.”

For their study, the team reviewed the records of 498 patients aged 21-79 years at a dermatology outpatient clinic who were deemed by an experienced dermatologist to be at risk of any type of skin cancer.

Among these patients, 295 individuals had a history of past or present cutaneous malignancy, with 100 diagnosed with melanoma, 213 with basal cell carcinoma, and 41 with squamous cell carcinoma. A further 70 subjects had cancer elsewhere, including breast, prostate, kidney, bladder, intestine, and blood cancers.

A subgroup of 96 patients were immunocompromised and were considered separately.

The 402 remaining patients were categorized, based on their self-reported use of oral vitamin D preparations, as nonusers (n = 99), occasional users (n = 126), and regular users (n = 177).

Regular use of vitamin D was associated with being more educated (P = .032), less frequent outdoor working (P = .003), lower tobacco pack years (P = .001), and more frequent solarium exposure (P = .002).

There was no significant association between vitamin D use and photoaging, actinic keratoses, nevi, basal or squamous cell carcinoma, body mass index, or self-estimated lifetime exposure to sunlight or sunburns.

However, there were significant associations between regular use of vitamin D and a lower incidence of melanoma and other cancer types.

There were significantly fewer individuals in the regular vitamin D use group with a past or present history of melanoma when compared with the nonuse group, at 18.1% vs. 32.3% (P = .021), or any type of skin cancer, at 62.1% vs. 74.7% (P = .027).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that regular vitamin D use was significantly associated with a reduced melanoma risk, at an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.447 (P = .016).

Occasional use was associated with a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk, with an odds ratio versus nonuse of 0.540 (P = .08).

For any type of skin cancers, regular vitamin D use was associated with an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.478 (P = .032), while that for occasional vitamin D use was 0.543 (P = .061).

“Somewhat similar” results were obtained when the investigators looked at the subgroup of immunocompromised individuals, although they note that “the number of subjects was low.”

The study was supported by the Cancer Center of Eastern Finland of the University of Eastern Finland, the Finnish Cancer Research Foundation, and the VTR-funding of Kuopio University Hospital. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. They also found a trend for benefit with occasional use.

The study, published in Melanoma Research, involved almost 500 individuals attending a dermatology clinic who reported on their use of vitamin D supplements.

Regular users had a significant 55% reduction in the odds of having a past or present melanoma diagnosis, while occasional use was associated with a nonsignificant 46% reduction. The reduction was similar for all skin cancer types.

However, senior author Ilkka T. Harvima, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio (Finland) University Hospital, warned there are limitations to the study.

Despite adjustment for several possible confounding factors, “it is still possible that some other, yet unidentified or untested, factors can still confound the present result,” he said.

Consequently, “the causal link between vitamin D and melanoma cannot be confirmed by the present results,” Dr. Harvima said in a statement.

Even if the link were to be proven, “the question about the optimal dose of oral vitamin D in order to for it to have beneficial effects remains to be answered,” he said.

“Until we know more, national intake recommendations should be followed.”

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers has been increasing steadily in Western populations, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals, the authors pointed out, and they attributed the rise to an increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

While ultraviolet radiation exposure is a well-known risk factor, “the other side of the coin is that public sun protection campaigns have led to alerts that insufficient sun exposure is a significant public health problem, resulting in insufficient vitamin D status.”

For their study, the team reviewed the records of 498 patients aged 21-79 years at a dermatology outpatient clinic who were deemed by an experienced dermatologist to be at risk of any type of skin cancer.

Among these patients, 295 individuals had a history of past or present cutaneous malignancy, with 100 diagnosed with melanoma, 213 with basal cell carcinoma, and 41 with squamous cell carcinoma. A further 70 subjects had cancer elsewhere, including breast, prostate, kidney, bladder, intestine, and blood cancers.

A subgroup of 96 patients were immunocompromised and were considered separately.

The 402 remaining patients were categorized, based on their self-reported use of oral vitamin D preparations, as nonusers (n = 99), occasional users (n = 126), and regular users (n = 177).

Regular use of vitamin D was associated with being more educated (P = .032), less frequent outdoor working (P = .003), lower tobacco pack years (P = .001), and more frequent solarium exposure (P = .002).

There was no significant association between vitamin D use and photoaging, actinic keratoses, nevi, basal or squamous cell carcinoma, body mass index, or self-estimated lifetime exposure to sunlight or sunburns.

However, there were significant associations between regular use of vitamin D and a lower incidence of melanoma and other cancer types.

There were significantly fewer individuals in the regular vitamin D use group with a past or present history of melanoma when compared with the nonuse group, at 18.1% vs. 32.3% (P = .021), or any type of skin cancer, at 62.1% vs. 74.7% (P = .027).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that regular vitamin D use was significantly associated with a reduced melanoma risk, at an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.447 (P = .016).

Occasional use was associated with a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk, with an odds ratio versus nonuse of 0.540 (P = .08).

For any type of skin cancers, regular vitamin D use was associated with an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.478 (P = .032), while that for occasional vitamin D use was 0.543 (P = .061).

“Somewhat similar” results were obtained when the investigators looked at the subgroup of immunocompromised individuals, although they note that “the number of subjects was low.”

The study was supported by the Cancer Center of Eastern Finland of the University of Eastern Finland, the Finnish Cancer Research Foundation, and the VTR-funding of Kuopio University Hospital. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. They also found a trend for benefit with occasional use.

The study, published in Melanoma Research, involved almost 500 individuals attending a dermatology clinic who reported on their use of vitamin D supplements.

Regular users had a significant 55% reduction in the odds of having a past or present melanoma diagnosis, while occasional use was associated with a nonsignificant 46% reduction. The reduction was similar for all skin cancer types.

However, senior author Ilkka T. Harvima, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio (Finland) University Hospital, warned there are limitations to the study.

Despite adjustment for several possible confounding factors, “it is still possible that some other, yet unidentified or untested, factors can still confound the present result,” he said.

Consequently, “the causal link between vitamin D and melanoma cannot be confirmed by the present results,” Dr. Harvima said in a statement.

Even if the link were to be proven, “the question about the optimal dose of oral vitamin D in order to for it to have beneficial effects remains to be answered,” he said.

“Until we know more, national intake recommendations should be followed.”

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers has been increasing steadily in Western populations, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals, the authors pointed out, and they attributed the rise to an increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

While ultraviolet radiation exposure is a well-known risk factor, “the other side of the coin is that public sun protection campaigns have led to alerts that insufficient sun exposure is a significant public health problem, resulting in insufficient vitamin D status.”

For their study, the team reviewed the records of 498 patients aged 21-79 years at a dermatology outpatient clinic who were deemed by an experienced dermatologist to be at risk of any type of skin cancer.

Among these patients, 295 individuals had a history of past or present cutaneous malignancy, with 100 diagnosed with melanoma, 213 with basal cell carcinoma, and 41 with squamous cell carcinoma. A further 70 subjects had cancer elsewhere, including breast, prostate, kidney, bladder, intestine, and blood cancers.

A subgroup of 96 patients were immunocompromised and were considered separately.

The 402 remaining patients were categorized, based on their self-reported use of oral vitamin D preparations, as nonusers (n = 99), occasional users (n = 126), and regular users (n = 177).

Regular use of vitamin D was associated with being more educated (P = .032), less frequent outdoor working (P = .003), lower tobacco pack years (P = .001), and more frequent solarium exposure (P = .002).

There was no significant association between vitamin D use and photoaging, actinic keratoses, nevi, basal or squamous cell carcinoma, body mass index, or self-estimated lifetime exposure to sunlight or sunburns.

However, there were significant associations between regular use of vitamin D and a lower incidence of melanoma and other cancer types.

There were significantly fewer individuals in the regular vitamin D use group with a past or present history of melanoma when compared with the nonuse group, at 18.1% vs. 32.3% (P = .021), or any type of skin cancer, at 62.1% vs. 74.7% (P = .027).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that regular vitamin D use was significantly associated with a reduced melanoma risk, at an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.447 (P = .016).

Occasional use was associated with a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk, with an odds ratio versus nonuse of 0.540 (P = .08).

For any type of skin cancers, regular vitamin D use was associated with an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.478 (P = .032), while that for occasional vitamin D use was 0.543 (P = .061).

“Somewhat similar” results were obtained when the investigators looked at the subgroup of immunocompromised individuals, although they note that “the number of subjects was low.”

The study was supported by the Cancer Center of Eastern Finland of the University of Eastern Finland, the Finnish Cancer Research Foundation, and the VTR-funding of Kuopio University Hospital. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MELANOMA RESEARCH

Early retirement and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad cognitive decline

The ‘scheme’ in the name should have been a clue

Retirement. The shiny reward to a lifetime’s worth of working and saving. We’re all literally working to get there, some of us more to get there early, but current research reveals that early retirement isn’t the relaxing finish line we dream about, cognitively speaking.

Researchers at Binghamton (N.Y.) University set out to examine just how retirement plans affect cognitive performance. They started off with China’s New Rural Pension Scheme (scheme probably has a less negative connotation in Chinese), a plan that financially aids the growing rural retirement-age population in the country. Then they looked at data from the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey, which tests cognition with a focus on episodic memory and parts of intact mental status.

What they found was the opposite of what you would expect out of retirees with nothing but time on their hands.

The pension program, which had been in place for almost a decade, led to delayed recall, especially among women, supporting “the mental retirement hypothesis that decreased mental activity results in worsening cognitive skills,” the investigators said in a written statement.

There also was a drop in social engagement, with lower rates of volunteering and social interaction than people who didn’t receive the pension. Some behaviors, like regular alcohol consumption, did improve over the previous year, as did total health in general, but “the adverse effects of early retirement on mental and social engagement significantly outweigh the program’s protective effect on various health behaviors,” Plamen Nikolov, PhD, said about his research.

So if you’re looking to retire early, don’t skimp on the crosswords and the bingo nights. Stay busy in a good way. Your brain will thank you.

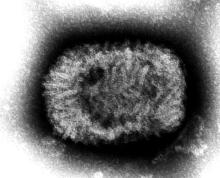

Indiana Jones and the First Smallpox Ancestor

Smallpox was, not that long ago, one of the most devastating diseases known to humanity, killing 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Eradicating it has to be one of medicine’s crowning achievements. Now it can only be found in museums, which is where it belongs.

Here’s the thing with smallpox though: For all it did to us, we know frustratingly little about where it came from. Until very recently, the best available genetic evidence placed its emergence in the 17th century, which clashes with historical data. You know what that means, right? It’s time to dig out the fedora and whip, cue the music, and dig into a recently published study spanning continents in search of the mythical smallpox origin story.

We pick up in 2020, when genetic evidence definitively showed smallpox in a Viking burial site, moving the disease’s emergence a thousand years earlier. Which is all well and good, but there’s solid visual evidence that Egyptian pharaohs were dying of smallpox, as their bodies show the signature scarring. Historians were pretty sure smallpox went back about 4,000 years, but there was no genetic material to prove it.

Since there aren’t any 4,000-year-old smallpox germs laying around, the researchers chose to attack the problem another way – by burning down a Venetian catacomb, er, conducting a analysis of historical smallpox genetics to find the virus’s origin. By analyzing the genomes of various strains at different periods of time, they were able to determine that the variola virus had a definitive common ancestor. Some of the genetic components in the Viking-age sample, for example, persisted until the 18th century.

Armed with this information, the scientists determined that the first smallpox ancestor emerged about 3,800 years ago. That’s very close to the historians’ estimate for the disease’s emergence. Proof at last of smallpox’s truly ancient origin. One might even say the researchers chose wisely.

The only hall of fame that really matters

LOTME loves the holiday season – the food, the gifts, the radio stations that play nothing but Christmas music – but for us the most wonderful time of the year comes just a bit later. No, it’s not our annual Golden Globes slap bet. Nope, not even the “excitement” of the College Football Playoff National Championship. It’s time for the National Inventors Hall of Fame to announce its latest inductees, and we could hardly sleep last night after putting cookies out for Thomas Edison. Fasten your seatbelts!

- Robert G. Bryant is a NASA chemist who developed Langley Research Center-Soluble Imide (yes, that’s the actual name) a polymer used as an insulation material for leads in implantable cardiac resynchronization therapy devices.

- Rory Cooper is a biomedical engineer who was paralyzed in a bicycle accident. His work has improved manual and electric wheelchairs and advanced the health, mobility, and social inclusion of people with disabilities and older adults. He is also the first NIHF inductee named Rory.

- Katalin Karikó, a biochemist, and Drew Weissman, an immunologist, “discovered how to enable messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) to enter cells without triggering the body’s immune system,” NIHF said, and that laid the foundation for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. That, of course, led to the antivax movement, which has provided so much LOTME fodder over the years.

- Angela Hartley Brodie was a biochemist who discovered and developed a class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors, which can stop the production of hormones that fuel cancer cell growth and are used to treat breast cancer in 500,000 women worldwide each year.

We can’t mention all of the inductees for 2023 (our editor made that very clear), but we would like to offer a special shout-out to brothers Cyril (the first Cyril in the NIHF, by the way) and Louis Keller, who invented the world’s first compact loader, which eventually became the Bobcat skid-steer loader. Not really medical, you’re probably thinking, but we’re sure that someone, somewhere, at some time, used one to build a hospital, landscape a hospital, or clean up after the demolition of a hospital.

The ‘scheme’ in the name should have been a clue

Retirement. The shiny reward to a lifetime’s worth of working and saving. We’re all literally working to get there, some of us more to get there early, but current research reveals that early retirement isn’t the relaxing finish line we dream about, cognitively speaking.

Researchers at Binghamton (N.Y.) University set out to examine just how retirement plans affect cognitive performance. They started off with China’s New Rural Pension Scheme (scheme probably has a less negative connotation in Chinese), a plan that financially aids the growing rural retirement-age population in the country. Then they looked at data from the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey, which tests cognition with a focus on episodic memory and parts of intact mental status.

What they found was the opposite of what you would expect out of retirees with nothing but time on their hands.

The pension program, which had been in place for almost a decade, led to delayed recall, especially among women, supporting “the mental retirement hypothesis that decreased mental activity results in worsening cognitive skills,” the investigators said in a written statement.

There also was a drop in social engagement, with lower rates of volunteering and social interaction than people who didn’t receive the pension. Some behaviors, like regular alcohol consumption, did improve over the previous year, as did total health in general, but “the adverse effects of early retirement on mental and social engagement significantly outweigh the program’s protective effect on various health behaviors,” Plamen Nikolov, PhD, said about his research.

So if you’re looking to retire early, don’t skimp on the crosswords and the bingo nights. Stay busy in a good way. Your brain will thank you.

Indiana Jones and the First Smallpox Ancestor

Smallpox was, not that long ago, one of the most devastating diseases known to humanity, killing 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Eradicating it has to be one of medicine’s crowning achievements. Now it can only be found in museums, which is where it belongs.

Here’s the thing with smallpox though: For all it did to us, we know frustratingly little about where it came from. Until very recently, the best available genetic evidence placed its emergence in the 17th century, which clashes with historical data. You know what that means, right? It’s time to dig out the fedora and whip, cue the music, and dig into a recently published study spanning continents in search of the mythical smallpox origin story.

We pick up in 2020, when genetic evidence definitively showed smallpox in a Viking burial site, moving the disease’s emergence a thousand years earlier. Which is all well and good, but there’s solid visual evidence that Egyptian pharaohs were dying of smallpox, as their bodies show the signature scarring. Historians were pretty sure smallpox went back about 4,000 years, but there was no genetic material to prove it.

Since there aren’t any 4,000-year-old smallpox germs laying around, the researchers chose to attack the problem another way – by burning down a Venetian catacomb, er, conducting a analysis of historical smallpox genetics to find the virus’s origin. By analyzing the genomes of various strains at different periods of time, they were able to determine that the variola virus had a definitive common ancestor. Some of the genetic components in the Viking-age sample, for example, persisted until the 18th century.

Armed with this information, the scientists determined that the first smallpox ancestor emerged about 3,800 years ago. That’s very close to the historians’ estimate for the disease’s emergence. Proof at last of smallpox’s truly ancient origin. One might even say the researchers chose wisely.

The only hall of fame that really matters

LOTME loves the holiday season – the food, the gifts, the radio stations that play nothing but Christmas music – but for us the most wonderful time of the year comes just a bit later. No, it’s not our annual Golden Globes slap bet. Nope, not even the “excitement” of the College Football Playoff National Championship. It’s time for the National Inventors Hall of Fame to announce its latest inductees, and we could hardly sleep last night after putting cookies out for Thomas Edison. Fasten your seatbelts!

- Robert G. Bryant is a NASA chemist who developed Langley Research Center-Soluble Imide (yes, that’s the actual name) a polymer used as an insulation material for leads in implantable cardiac resynchronization therapy devices.

- Rory Cooper is a biomedical engineer who was paralyzed in a bicycle accident. His work has improved manual and electric wheelchairs and advanced the health, mobility, and social inclusion of people with disabilities and older adults. He is also the first NIHF inductee named Rory.

- Katalin Karikó, a biochemist, and Drew Weissman, an immunologist, “discovered how to enable messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) to enter cells without triggering the body’s immune system,” NIHF said, and that laid the foundation for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. That, of course, led to the antivax movement, which has provided so much LOTME fodder over the years.

- Angela Hartley Brodie was a biochemist who discovered and developed a class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors, which can stop the production of hormones that fuel cancer cell growth and are used to treat breast cancer in 500,000 women worldwide each year.

We can’t mention all of the inductees for 2023 (our editor made that very clear), but we would like to offer a special shout-out to brothers Cyril (the first Cyril in the NIHF, by the way) and Louis Keller, who invented the world’s first compact loader, which eventually became the Bobcat skid-steer loader. Not really medical, you’re probably thinking, but we’re sure that someone, somewhere, at some time, used one to build a hospital, landscape a hospital, or clean up after the demolition of a hospital.

The ‘scheme’ in the name should have been a clue

Retirement. The shiny reward to a lifetime’s worth of working and saving. We’re all literally working to get there, some of us more to get there early, but current research reveals that early retirement isn’t the relaxing finish line we dream about, cognitively speaking.

Researchers at Binghamton (N.Y.) University set out to examine just how retirement plans affect cognitive performance. They started off with China’s New Rural Pension Scheme (scheme probably has a less negative connotation in Chinese), a plan that financially aids the growing rural retirement-age population in the country. Then they looked at data from the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey, which tests cognition with a focus on episodic memory and parts of intact mental status.

What they found was the opposite of what you would expect out of retirees with nothing but time on their hands.

The pension program, which had been in place for almost a decade, led to delayed recall, especially among women, supporting “the mental retirement hypothesis that decreased mental activity results in worsening cognitive skills,” the investigators said in a written statement.

There also was a drop in social engagement, with lower rates of volunteering and social interaction than people who didn’t receive the pension. Some behaviors, like regular alcohol consumption, did improve over the previous year, as did total health in general, but “the adverse effects of early retirement on mental and social engagement significantly outweigh the program’s protective effect on various health behaviors,” Plamen Nikolov, PhD, said about his research.

So if you’re looking to retire early, don’t skimp on the crosswords and the bingo nights. Stay busy in a good way. Your brain will thank you.

Indiana Jones and the First Smallpox Ancestor

Smallpox was, not that long ago, one of the most devastating diseases known to humanity, killing 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Eradicating it has to be one of medicine’s crowning achievements. Now it can only be found in museums, which is where it belongs.

Here’s the thing with smallpox though: For all it did to us, we know frustratingly little about where it came from. Until very recently, the best available genetic evidence placed its emergence in the 17th century, which clashes with historical data. You know what that means, right? It’s time to dig out the fedora and whip, cue the music, and dig into a recently published study spanning continents in search of the mythical smallpox origin story.

We pick up in 2020, when genetic evidence definitively showed smallpox in a Viking burial site, moving the disease’s emergence a thousand years earlier. Which is all well and good, but there’s solid visual evidence that Egyptian pharaohs were dying of smallpox, as their bodies show the signature scarring. Historians were pretty sure smallpox went back about 4,000 years, but there was no genetic material to prove it.

Since there aren’t any 4,000-year-old smallpox germs laying around, the researchers chose to attack the problem another way – by burning down a Venetian catacomb, er, conducting a analysis of historical smallpox genetics to find the virus’s origin. By analyzing the genomes of various strains at different periods of time, they were able to determine that the variola virus had a definitive common ancestor. Some of the genetic components in the Viking-age sample, for example, persisted until the 18th century.

Armed with this information, the scientists determined that the first smallpox ancestor emerged about 3,800 years ago. That’s very close to the historians’ estimate for the disease’s emergence. Proof at last of smallpox’s truly ancient origin. One might even say the researchers chose wisely.

The only hall of fame that really matters

LOTME loves the holiday season – the food, the gifts, the radio stations that play nothing but Christmas music – but for us the most wonderful time of the year comes just a bit later. No, it’s not our annual Golden Globes slap bet. Nope, not even the “excitement” of the College Football Playoff National Championship. It’s time for the National Inventors Hall of Fame to announce its latest inductees, and we could hardly sleep last night after putting cookies out for Thomas Edison. Fasten your seatbelts!

- Robert G. Bryant is a NASA chemist who developed Langley Research Center-Soluble Imide (yes, that’s the actual name) a polymer used as an insulation material for leads in implantable cardiac resynchronization therapy devices.

- Rory Cooper is a biomedical engineer who was paralyzed in a bicycle accident. His work has improved manual and electric wheelchairs and advanced the health, mobility, and social inclusion of people with disabilities and older adults. He is also the first NIHF inductee named Rory.

- Katalin Karikó, a biochemist, and Drew Weissman, an immunologist, “discovered how to enable messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) to enter cells without triggering the body’s immune system,” NIHF said, and that laid the foundation for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. That, of course, led to the antivax movement, which has provided so much LOTME fodder over the years.

- Angela Hartley Brodie was a biochemist who discovered and developed a class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors, which can stop the production of hormones that fuel cancer cell growth and are used to treat breast cancer in 500,000 women worldwide each year.

We can’t mention all of the inductees for 2023 (our editor made that very clear), but we would like to offer a special shout-out to brothers Cyril (the first Cyril in the NIHF, by the way) and Louis Keller, who invented the world’s first compact loader, which eventually became the Bobcat skid-steer loader. Not really medical, you’re probably thinking, but we’re sure that someone, somewhere, at some time, used one to build a hospital, landscape a hospital, or clean up after the demolition of a hospital.

When Patients Make Unexpected Medical Choices

Due to advances in medicine, people are living longer with the aid of increased options for life-prolonging treatments. These treatment options may improve the quantity but not necessarily the quality of life.1

Kidney failure can be treated with renal replacement therapy (dialysis or renal transplantation) or supportive care.2 In 2017, the global prevalence of kidney failure was about 5.3 to 9.7 million.3 In the United States, about 500,000 patients are receiving maintenance dialysis for end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and about 1 in 4 will stop dialysis before death, coupled with hospice enrollment.4 ESRD is 2 times more prevalent among veterans than in nonveterans, which can be due in part to high rates of comorbid predisposing conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and advanced age, among others.5 The decision to discontinue dialysis and receive hospice care tends to be more difficult than choosing to withhold or forego dialysis.6

A study conducted among patients who were taken off hemodialysis before death reported that the 2 most common reasons for the withdrawal were acute medical complications and frailty.7 A retrospective study among patients with ESRD receiving hemodialysis highlighted the underutilization of hospice care in this patient population.8 The study also found that those patients who were aged > 75 years, had poor functional status, and had dialysis-related complications, such as sepsis and anemia, were more likely to elect withdrawal of hemodialysis. There was no difference in overall survival or quality of life among patients who were aged ≥ 75 years with multiple comorbidities and functional impairment who elected conservative management vs those who started dialysis.8 Long-term continuous dialysis has been associated with a lower quality of life, increased dependence on others, and a variety of symptoms, such as pain, nausea, insomnia, anxiety, or depression.9

Conservative Care vs Medical Paternalism

In the United States, it is unusual for patients with ESRD to choose conservative care, and supportive services are less available for those who do compared with patients with ESRD in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Canada.10 A study looking at a small number of US nephrologists has shown they may have limited experience in caring for patients who forego dialysis and they are not comfortable offering conservative management over dialysis.10 Another small study from Sweden also showed that many nephrologists do not feel prepared for end-of-life care and conversations.11

Patients often rely on knowledgeable recommendations from medical experts. However, medical paternalism occurs when a physician makes decisions deemed to be in the patient’s best interest but are against the patient’s wishes or when the patient is unable to give their consent.12 Hard paternalism occurs when the patient is competent to make their own medical decisions, while soft paternalism occurs when a patient is not competent to make their own medical decisions.13

Patient autonomy is widely recognized as an ethical principle in medicine. It recognizes patients as well-informed decision makers who may act without excessive influence to make intentional determinations on their own behalf.14 Autonomy can be exercised at any point during the health care process.12 Although ethical and legal guidelines encourage physicians to recommend appropriate treatment, medical opinion cannot overrule the wishes of a competent patient who refuses treatment.12

Case Presentation

Mr. S presented to the emergency department at a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center with abdominal pain from recurrent pancreatitis. The patient aged > 65 years had a history of depression, ESRD, and was receiving hemodialysis. A computed tomography scan revealed a new pancreatic mass, and he was referred to the palliative care (PC) department nurse practitioner (NP) for a goals-of-care discussion. PC was informed to assist with hospice care initiation: The patient elected a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) code status and hospice care.

At the consultation, Mr. S stated that he had decided to forego life-prolonging treatments, including hemodialysis, and declined further evaluation for his pancreatic mass. He shared a good understanding of concerns for malignancy with his mass but did not wish to pursue further diagnostics as he knew his life expectancy was very limited without dialysis. He had been dependent on hemodialysis for the past 10 years. He had briefly received hospice care 5 years before but changed his mind and decided to pursue standard care, including life-prolonging dialysis treatments. He reported no depression, suicidal ideation, or intentions of hastening his death. He stated that he was just physically tired from his ongoing dialysis, recurrent hospitalizations, and being repeatedly subjected to diagnostic tests. Mr. S added that he had discussed his plan with his family, including his son and sister-in-law who is married to his brother. Mr. S previously identified his brother as his surrogate decision maker.

Mr. S shared that his brother had sustained a traumatic brain injury and was now unable to engage in a meaningful conversation. He shared that his family supported his decision. He also recognized that with his debility, he would need inpatient hospice care. On finding out that Mr. S’s brother was no longer able to act as the surrogate decision maker, the PC NP asked whether he wanted her to contact his son to share the outcome of their visit. The patient declined, adding that he had discussed his care plans with his family and did not feel that his health care team needed to have additional discussions with them.

Mr. S also reported chronic, recurrent right upper quadrant pain. He was prescribed oxycodone 10 mg every 4 hours as needed; however, it did little to control his pain. He also reported generalized pruritus, a complication of his renal failure.

After 1 week, Mr. S was transferred to the inpatient hospice unit. At that time, he allowed the hospice team to contact his son for medical updates and identified him as the primary point of contact for the hospice team if the need arose to reach his family. Due to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, Mr. S had virtual video visits with his family. Mr. S developed intermittent confusion and worsening fatigue over time. His son was informed of his deteriorating condition and visited his father. Mr. S died peacefully 2 days later with his family present.

Multidisciplinary Inputs on the Case

Medicine. In discussing the case with medicine, the PC NP was informed that the goals the patient had for his care, which included stopping dialysis, having a DNR code status and pursuing hospice care, along with the patient’s pain symptoms prompted the PC consultation. The resident also shared concerns about the patient’s refusal to have his surrogate decision maker and family contacted regarding his decisions for his care.

Palliative care. After meeting with the patient and assisting in identifying goals for care, the PC NP recommended initiation of hospice care in the hospital while the patient awaited transfer to the inpatient hospice unit. The PC NP also recommended a psychiatric evaluation to rule out untreated depression that might influence the patient’s decision making. A follow-up visit with nephrology was also recommended. Optimal management of his distressing physical symptoms was recommended, including prescribing hydromorphone instead of oxycodone for his pain and starting a topical emollient for pruritus.

Nephrology. The patient’s electronic health records (EHR) showed that he informed nephrology of his desire to pursue hospice care and that he decided against further dialysis, including as-needed dialysis for comfort. The records also indicated that the patient understood the consequences of discontinuing dialysis.

Psychiatry. The patient’s EHR also showed that during his psychiatric visits, Mr. S reported he had no thoughts of suicide, and it was against his spiritual beliefs. He said he made his own medical decisions and expressed that his health care team should not attempt to change his mind. He also said he understood that stopping dialysis could lead to early death. He stated he had a close relationship with his family and discussed his medical decisions with them. He was tearful at times when he talked about his family. Mr. S shared his frustration about repeatedly being asked the same questions on succeeding visits.

After evaluation, psychiatry diagnosed Mr. S with mood disorder with depressive features and he was prescribed methylphenidate 5 mg daily and sertraline 25 mg daily. They also recommended continuing to offer dialysis in a supportive manner since the patient had changed his mind about hospice in the past. However, psychiatry followed the patient daily for 5 days and concluded that his medical decisions were not clouded by mood symptoms.

Discussion

Patients who are aged > 65 years and on dialysis are more likely to experience higher rates of hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, procedures, and death in the hospital compared with patients who have cancer or heart failure. They also use hospice services less.15 Often this is not consistent with a patient’s wishes but may occur due to limited discussion of goals, values, and preferences between physician and patient.15 Many nephrologists do not engage in these conversations for fear of upsetting patients, their perceived lack of skill in prognostication and discussing the topic, or the lack of time to have the conversation.15 It is important to have an honest and open communication with patients that allows them to be fully informed as they make their medical decisions and exercise their autonomy.

Medicare hospice guidelines also are used to help determine hospice appropriateness among veterans in the VA. Medicare requires enrollees to discontinue disease-modifying treatment for the medical condition leading to their hospice diagnosis, which can result in late hospice referrals and shorter hospice stays.16 Even though hospice referrals for patients with ESRD have increased over time, they are still happening close to the time of death, and patients’ health care utilization near the end of life remains unchanged.16 According to Medicare, patients qualify for hospice care if they are terminally ill (defined as having a life expectancy of ≤ 6 months), choose comfort care over curative care for their terminal illness, and sign a statement electing hospice care over treatments for their terminal illness.17 A DNR order is not a condition for hospice admission.18

The VA defines hospice care as comfort care provided to patients with a terminal condition, a life expectancy of ≤ 6 months, and who are no longer seeking treatment other than those that are palliative.19 Based on his ESRD, Mr. S was qualified for hospice care, and his goals for care were consistent with the hospice philosophy. Most families of patients who elected to withdraw dialysis reported a good death, using the criteria of the duration of dying, discomfort, and psychosocial circumstances.20

Role of HCPs

Health care practitioners (HCPs) are expected to help patients understand the risks and benefits of their choices and its alternative, align patients’ goals with those risks and benefits, and assist patients in making choices that promote their goals and autonomy.21 Family members are often not involved in medical decision making when patients have the capacity to make their own decisions.22 Patients will also have to give permission for protected health information to be shared with their family members.22 On the other hand, families have been shown to provide valuable emotional support to patients and are considered second patients themselves in the sense that they can be impacted by patients’ clinical situation.22 Families may also need care, time, and attention from HCPs.22

Mr. S was found capable of making his own decisions, and part of that decision was that his family not to be present for the goals-of-care discussion. He added that he would discuss the care decisions with his family. At the time of registering for VA health care services, Mr. S had provided his health care team with his brother and sister-in-law’s emergency contact information as well as named his brother surrogate decision maker. As Mr. S’s condition was expected to rapidly decline wthout dialysis, the HCPs would be able to notify family members once his condition changed, including death.

Neuroplasticity changes can contribute to chronic pain that may also lead to depression.23 Chronic pain and depression may involve the same brain structures, neurotransmitters, and signaling pathway.23 Factors leading to chronic pain and depression include decreased availability of monoamine neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the central nervous system, decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor, inflammatory response, and increased glutamate activity.23 Depression and hopelessness have been associated with the desire to hasten death among patients with a terminal illness.24 Worse mental health has been associated with the desire to hasten death among patients who are older and functionally impaired.25 It was important to optimize Mr. S’s treatment for pain and depression to ensure that these factors were not influencing his medical decisions.

With increasing recognition of the need to improve quality of life, health care utilization, and provide care consistent with patients’ goals in nephrology, the concept of renal PC is emerging but remains limited.26 The need to improve supportive care or PC for patients starting on dialysis for ESRD is high as these patients tend to be older (aged > 75 years), have high rates of cardiovascular comorbidities, can have coexisting cognitive impairment and functional debility, and have an adjusted mortality rate of up to 32.5% within 1 year of starting dialysis.26 Some ways to enhance renal PC programs include incorporating PC skill development and training within nephrology fellowships, educating patients with chronic and ESRD about PC and options for medical management without dialysis, and increasing the collaboration between nephrology and PC.26

Outcomes and Implications

Respect for the ethical principle of autonomy is paramount in health care. Patients should be able to give informed consent for treatment decisions without undue influence from their HCPs and should be able to withdraw that consent at any point during treatment. Factors that may influence patients’ ability to make medical decisions should be considered, including untreated or poorly treated symptoms. The involvement of PC helps optimize symptom management, provide support, and assist in goals-of-care discussions. Advanced practice PC nurses can offer other members of the health care team additional information and support in end-of-life care. Family involvement should be encouraged even for patients who can make their own medical decisions for emotional support and to assist families in what could be a traumatic event, such as the loss of a loved one.

The desire to pursue a comfort-focused approach to terminal illness and stop disease-modifying treatments are criteria for hospice care. An interdisciplinary approach to end-of-life care is beneficial, and every specialty should be equipped to engage in honest communication and skillful prognostication. These conversations should start early in the course of a terminal illness. Multiple factors contribute to poor clinical outcomes among patients with ESRD even with renal replacement therapy, such as dialysis. There is a need to improve PC training in the field of nephrology.

Conclusions

Mr. S was able to choose to withdraw potentially life-prolonging treatments with the support of his family and HCPs. He was able to continue receiving high-quality care and treatment in accordance with his wishes and goals for his care. The provision of interdisciplinary care that focused on supporting him allowed for his peaceful and comfortable death.

1. Carr D, Luth EA. Well-being at the end of life. Annu Rev Sociol. 2019;45:515-534. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022524

2. Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, et al. Site of death, place of care, and health care transitions among US Medicare beneficiaries, 2000-2015. JAMA. 2018;320(3):264-271. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8981

3. Himmelfarb J, Vanholder R, Mehrotra R, Tonelli M. The current and future landscape of dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(10):573-585. doi:10.1038/s41581-020-0315-4

4. Richards CA, Hebert PL, Liu CF, et al. Association of family ratings of quality of end-of-life care with stopping dialysis treatment and receipt of hospice services. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913115. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13115

5. Fischer MJ, Kourany WM, Sovern K, Forrester K, Griffin C, Lightner N, Loftus S, Murphy K, Roth G, Palevsky PM, Crowley ST. Development, implementation and user experience of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) dialysis dashboard. BMC Nephrol. 2020 Apr 16;21(1):136. doi:10.1186/s12882-020-01798-6

6. Schwarze ML, Schueller K, Jhagroo RA. Hospice use and end-of-life care for patients with end-stage renal disease: too little, too late. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):799-801.doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1078

7. Chen JC, Thorsteinsdottir B, Vaughan LE, et al. End of life, withdrawal, and palliative care utilization among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(8):1172-1179. doi:10.2215/CJN.00590118

8. Chen HC, Wu CY, Hsieh HY, He JS, Hwang SJ, Hsieh HM. Predictors and assessment of hospice use for end-stage renal disease patients in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19(1):85. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010085

9. Rak A, Raina R, Suh TT, et al. Palliative care for patients with end-stage renal disease: approach to treatment that aims to improve quality of life and relieve suffering for patients (and families) with chronic illnesses. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10(1):68-73. doi.10.1093/ckj/sfw10510. Wong SPY, Boyapati S, Engelberg RA, Thorsteinsdottir B, Taylor JS, O’Hare AM. Experiences of US nephrologists in the delivery of conservative care to patients with advanced kidney disease: a national qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(2):167-176. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.07.006

11. Axelsson L, Benzein E, Lindberg J, Persson C. End-of-life and palliative care of patients on maintenance hemodialysis treatment: a focus group study. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(1):89. doi:10.1186/s12904-019-0481-y

12. Tweeddale MG. Grasping the nettle—what to do when patients withdraw their consent for treatment: (a clinical perspective on the case of Ms B). J Med Ethics. 2002;28(4):236-237. doi:10.1136/jme.28.4.236

13. Lynøe N, Engström I, Juth N. How to reveal disguised paternalism: version 2.0. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):170. doi:10.1186/s12910-021-00739-8

14. Murgic L, Hébert PC, Sovic S, Pavlekovic G. Paternalism and autonomy: views of patients and providers in a transitional (post-communist) country. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16(1):65. doi:10.1186/s12910-015-0059-z

15. Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD. Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(5):854-863. doi:10.2215/CJN.05760516

16. Wachterman MW, Hailpern SM, Keating NL, Kurella Tamura M, O’Hare AM. Association between hospice length of stay, health care utilization, and Medicare costs at the end of life among patients who received maintenance hemodialysis. JAMA Int Med. 2018;178(6):792-799. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0256

17. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospice care. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/hospice-care

18. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Ethical behavior and consumer rights. Standards of Practice for Hospice Programs Professional Development and Resource Series. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Standards_Hospice_2018.pdf

19. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Geriatrics and extended care. Updated October 5, 2022. Accessed August 29, 2022. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/Hospice_Care.asp

20. Cohen LM, McCue JD, Germain M, Kjellstrand CM. Dialysis discontinuation. A ‘good’ death? Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(1):42-47.

21. Ubel PA, Scherr KA, Fagerlin A. Autonomy: What’s shared decision making have to do with it? Am J Bioeth. 2018;18(2):W11-W12.doi:10.1080/15265161.2017.1409844

22. Laryionava, K, Pfeil TA, Dietrich M. et al. The second patient? Family members of cancer patients and their role in end-of-life decision making. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):29. doi:10.1186/s12904-018-0288-2

23. Sheng J, Liu S, Wang Y, Cui R, Zhang X. The link between depression and chronic pain: neural mechanisms in the brain. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:9724371. doi:10.1155/2017/9724371

24. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2907-2911. doi:10.1001/jama.284.22.2907

25. Sullivan M, Ormel J, Kempen GIJM, Tymstra T. Beliefs concerning death, dying, and hastening death among older, functionally impaired Dutch adults: a one-year longitudinal study. J Am Gec Soc. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04541.x26. Gelfand SL, Schell J, Eneanya ND. Palliative care in nephrology: the work and the workforce. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27(4):350-355.e1. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2020.02.007

Due to advances in medicine, people are living longer with the aid of increased options for life-prolonging treatments. These treatment options may improve the quantity but not necessarily the quality of life.1

Kidney failure can be treated with renal replacement therapy (dialysis or renal transplantation) or supportive care.2 In 2017, the global prevalence of kidney failure was about 5.3 to 9.7 million.3 In the United States, about 500,000 patients are receiving maintenance dialysis for end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and about 1 in 4 will stop dialysis before death, coupled with hospice enrollment.4 ESRD is 2 times more prevalent among veterans than in nonveterans, which can be due in part to high rates of comorbid predisposing conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and advanced age, among others.5 The decision to discontinue dialysis and receive hospice care tends to be more difficult than choosing to withhold or forego dialysis.6

A study conducted among patients who were taken off hemodialysis before death reported that the 2 most common reasons for the withdrawal were acute medical complications and frailty.7 A retrospective study among patients with ESRD receiving hemodialysis highlighted the underutilization of hospice care in this patient population.8 The study also found that those patients who were aged > 75 years, had poor functional status, and had dialysis-related complications, such as sepsis and anemia, were more likely to elect withdrawal of hemodialysis. There was no difference in overall survival or quality of life among patients who were aged ≥ 75 years with multiple comorbidities and functional impairment who elected conservative management vs those who started dialysis.8 Long-term continuous dialysis has been associated with a lower quality of life, increased dependence on others, and a variety of symptoms, such as pain, nausea, insomnia, anxiety, or depression.9

Conservative Care vs Medical Paternalism

In the United States, it is unusual for patients with ESRD to choose conservative care, and supportive services are less available for those who do compared with patients with ESRD in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Canada.10 A study looking at a small number of US nephrologists has shown they may have limited experience in caring for patients who forego dialysis and they are not comfortable offering conservative management over dialysis.10 Another small study from Sweden also showed that many nephrologists do not feel prepared for end-of-life care and conversations.11

Patients often rely on knowledgeable recommendations from medical experts. However, medical paternalism occurs when a physician makes decisions deemed to be in the patient’s best interest but are against the patient’s wishes or when the patient is unable to give their consent.12 Hard paternalism occurs when the patient is competent to make their own medical decisions, while soft paternalism occurs when a patient is not competent to make their own medical decisions.13

Patient autonomy is widely recognized as an ethical principle in medicine. It recognizes patients as well-informed decision makers who may act without excessive influence to make intentional determinations on their own behalf.14 Autonomy can be exercised at any point during the health care process.12 Although ethical and legal guidelines encourage physicians to recommend appropriate treatment, medical opinion cannot overrule the wishes of a competent patient who refuses treatment.12

Case Presentation

Mr. S presented to the emergency department at a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center with abdominal pain from recurrent pancreatitis. The patient aged > 65 years had a history of depression, ESRD, and was receiving hemodialysis. A computed tomography scan revealed a new pancreatic mass, and he was referred to the palliative care (PC) department nurse practitioner (NP) for a goals-of-care discussion. PC was informed to assist with hospice care initiation: The patient elected a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) code status and hospice care.

At the consultation, Mr. S stated that he had decided to forego life-prolonging treatments, including hemodialysis, and declined further evaluation for his pancreatic mass. He shared a good understanding of concerns for malignancy with his mass but did not wish to pursue further diagnostics as he knew his life expectancy was very limited without dialysis. He had been dependent on hemodialysis for the past 10 years. He had briefly received hospice care 5 years before but changed his mind and decided to pursue standard care, including life-prolonging dialysis treatments. He reported no depression, suicidal ideation, or intentions of hastening his death. He stated that he was just physically tired from his ongoing dialysis, recurrent hospitalizations, and being repeatedly subjected to diagnostic tests. Mr. S added that he had discussed his plan with his family, including his son and sister-in-law who is married to his brother. Mr. S previously identified his brother as his surrogate decision maker.

Mr. S shared that his brother had sustained a traumatic brain injury and was now unable to engage in a meaningful conversation. He shared that his family supported his decision. He also recognized that with his debility, he would need inpatient hospice care. On finding out that Mr. S’s brother was no longer able to act as the surrogate decision maker, the PC NP asked whether he wanted her to contact his son to share the outcome of their visit. The patient declined, adding that he had discussed his care plans with his family and did not feel that his health care team needed to have additional discussions with them.

Mr. S also reported chronic, recurrent right upper quadrant pain. He was prescribed oxycodone 10 mg every 4 hours as needed; however, it did little to control his pain. He also reported generalized pruritus, a complication of his renal failure.

After 1 week, Mr. S was transferred to the inpatient hospice unit. At that time, he allowed the hospice team to contact his son for medical updates and identified him as the primary point of contact for the hospice team if the need arose to reach his family. Due to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, Mr. S had virtual video visits with his family. Mr. S developed intermittent confusion and worsening fatigue over time. His son was informed of his deteriorating condition and visited his father. Mr. S died peacefully 2 days later with his family present.

Multidisciplinary Inputs on the Case

Medicine. In discussing the case with medicine, the PC NP was informed that the goals the patient had for his care, which included stopping dialysis, having a DNR code status and pursuing hospice care, along with the patient’s pain symptoms prompted the PC consultation. The resident also shared concerns about the patient’s refusal to have his surrogate decision maker and family contacted regarding his decisions for his care.

Palliative care. After meeting with the patient and assisting in identifying goals for care, the PC NP recommended initiation of hospice care in the hospital while the patient awaited transfer to the inpatient hospice unit. The PC NP also recommended a psychiatric evaluation to rule out untreated depression that might influence the patient’s decision making. A follow-up visit with nephrology was also recommended. Optimal management of his distressing physical symptoms was recommended, including prescribing hydromorphone instead of oxycodone for his pain and starting a topical emollient for pruritus.

Nephrology. The patient’s electronic health records (EHR) showed that he informed nephrology of his desire to pursue hospice care and that he decided against further dialysis, including as-needed dialysis for comfort. The records also indicated that the patient understood the consequences of discontinuing dialysis.

Psychiatry. The patient’s EHR also showed that during his psychiatric visits, Mr. S reported he had no thoughts of suicide, and it was against his spiritual beliefs. He said he made his own medical decisions and expressed that his health care team should not attempt to change his mind. He also said he understood that stopping dialysis could lead to early death. He stated he had a close relationship with his family and discussed his medical decisions with them. He was tearful at times when he talked about his family. Mr. S shared his frustration about repeatedly being asked the same questions on succeeding visits.

After evaluation, psychiatry diagnosed Mr. S with mood disorder with depressive features and he was prescribed methylphenidate 5 mg daily and sertraline 25 mg daily. They also recommended continuing to offer dialysis in a supportive manner since the patient had changed his mind about hospice in the past. However, psychiatry followed the patient daily for 5 days and concluded that his medical decisions were not clouded by mood symptoms.

Discussion

Patients who are aged > 65 years and on dialysis are more likely to experience higher rates of hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, procedures, and death in the hospital compared with patients who have cancer or heart failure. They also use hospice services less.15 Often this is not consistent with a patient’s wishes but may occur due to limited discussion of goals, values, and preferences between physician and patient.15 Many nephrologists do not engage in these conversations for fear of upsetting patients, their perceived lack of skill in prognostication and discussing the topic, or the lack of time to have the conversation.15 It is important to have an honest and open communication with patients that allows them to be fully informed as they make their medical decisions and exercise their autonomy.

Medicare hospice guidelines also are used to help determine hospice appropriateness among veterans in the VA. Medicare requires enrollees to discontinue disease-modifying treatment for the medical condition leading to their hospice diagnosis, which can result in late hospice referrals and shorter hospice stays.16 Even though hospice referrals for patients with ESRD have increased over time, they are still happening close to the time of death, and patients’ health care utilization near the end of life remains unchanged.16 According to Medicare, patients qualify for hospice care if they are terminally ill (defined as having a life expectancy of ≤ 6 months), choose comfort care over curative care for their terminal illness, and sign a statement electing hospice care over treatments for their terminal illness.17 A DNR order is not a condition for hospice admission.18

The VA defines hospice care as comfort care provided to patients with a terminal condition, a life expectancy of ≤ 6 months, and who are no longer seeking treatment other than those that are palliative.19 Based on his ESRD, Mr. S was qualified for hospice care, and his goals for care were consistent with the hospice philosophy. Most families of patients who elected to withdraw dialysis reported a good death, using the criteria of the duration of dying, discomfort, and psychosocial circumstances.20

Role of HCPs

Health care practitioners (HCPs) are expected to help patients understand the risks and benefits of their choices and its alternative, align patients’ goals with those risks and benefits, and assist patients in making choices that promote their goals and autonomy.21 Family members are often not involved in medical decision making when patients have the capacity to make their own decisions.22 Patients will also have to give permission for protected health information to be shared with their family members.22 On the other hand, families have been shown to provide valuable emotional support to patients and are considered second patients themselves in the sense that they can be impacted by patients’ clinical situation.22 Families may also need care, time, and attention from HCPs.22

Mr. S was found capable of making his own decisions, and part of that decision was that his family not to be present for the goals-of-care discussion. He added that he would discuss the care decisions with his family. At the time of registering for VA health care services, Mr. S had provided his health care team with his brother and sister-in-law’s emergency contact information as well as named his brother surrogate decision maker. As Mr. S’s condition was expected to rapidly decline wthout dialysis, the HCPs would be able to notify family members once his condition changed, including death.

Neuroplasticity changes can contribute to chronic pain that may also lead to depression.23 Chronic pain and depression may involve the same brain structures, neurotransmitters, and signaling pathway.23 Factors leading to chronic pain and depression include decreased availability of monoamine neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the central nervous system, decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor, inflammatory response, and increased glutamate activity.23 Depression and hopelessness have been associated with the desire to hasten death among patients with a terminal illness.24 Worse mental health has been associated with the desire to hasten death among patients who are older and functionally impaired.25 It was important to optimize Mr. S’s treatment for pain and depression to ensure that these factors were not influencing his medical decisions.

With increasing recognition of the need to improve quality of life, health care utilization, and provide care consistent with patients’ goals in nephrology, the concept of renal PC is emerging but remains limited.26 The need to improve supportive care or PC for patients starting on dialysis for ESRD is high as these patients tend to be older (aged > 75 years), have high rates of cardiovascular comorbidities, can have coexisting cognitive impairment and functional debility, and have an adjusted mortality rate of up to 32.5% within 1 year of starting dialysis.26 Some ways to enhance renal PC programs include incorporating PC skill development and training within nephrology fellowships, educating patients with chronic and ESRD about PC and options for medical management without dialysis, and increasing the collaboration between nephrology and PC.26

Outcomes and Implications

Respect for the ethical principle of autonomy is paramount in health care. Patients should be able to give informed consent for treatment decisions without undue influence from their HCPs and should be able to withdraw that consent at any point during treatment. Factors that may influence patients’ ability to make medical decisions should be considered, including untreated or poorly treated symptoms. The involvement of PC helps optimize symptom management, provide support, and assist in goals-of-care discussions. Advanced practice PC nurses can offer other members of the health care team additional information and support in end-of-life care. Family involvement should be encouraged even for patients who can make their own medical decisions for emotional support and to assist families in what could be a traumatic event, such as the loss of a loved one.

The desire to pursue a comfort-focused approach to terminal illness and stop disease-modifying treatments are criteria for hospice care. An interdisciplinary approach to end-of-life care is beneficial, and every specialty should be equipped to engage in honest communication and skillful prognostication. These conversations should start early in the course of a terminal illness. Multiple factors contribute to poor clinical outcomes among patients with ESRD even with renal replacement therapy, such as dialysis. There is a need to improve PC training in the field of nephrology.

Conclusions

Mr. S was able to choose to withdraw potentially life-prolonging treatments with the support of his family and HCPs. He was able to continue receiving high-quality care and treatment in accordance with his wishes and goals for his care. The provision of interdisciplinary care that focused on supporting him allowed for his peaceful and comfortable death.

Due to advances in medicine, people are living longer with the aid of increased options for life-prolonging treatments. These treatment options may improve the quantity but not necessarily the quality of life.1

Kidney failure can be treated with renal replacement therapy (dialysis or renal transplantation) or supportive care.2 In 2017, the global prevalence of kidney failure was about 5.3 to 9.7 million.3 In the United States, about 500,000 patients are receiving maintenance dialysis for end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and about 1 in 4 will stop dialysis before death, coupled with hospice enrollment.4 ESRD is 2 times more prevalent among veterans than in nonveterans, which can be due in part to high rates of comorbid predisposing conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and advanced age, among others.5 The decision to discontinue dialysis and receive hospice care tends to be more difficult than choosing to withhold or forego dialysis.6

A study conducted among patients who were taken off hemodialysis before death reported that the 2 most common reasons for the withdrawal were acute medical complications and frailty.7 A retrospective study among patients with ESRD receiving hemodialysis highlighted the underutilization of hospice care in this patient population.8 The study also found that those patients who were aged > 75 years, had poor functional status, and had dialysis-related complications, such as sepsis and anemia, were more likely to elect withdrawal of hemodialysis. There was no difference in overall survival or quality of life among patients who were aged ≥ 75 years with multiple comorbidities and functional impairment who elected conservative management vs those who started dialysis.8 Long-term continuous dialysis has been associated with a lower quality of life, increased dependence on others, and a variety of symptoms, such as pain, nausea, insomnia, anxiety, or depression.9

Conservative Care vs Medical Paternalism

In the United States, it is unusual for patients with ESRD to choose conservative care, and supportive services are less available for those who do compared with patients with ESRD in Europe, Asia, Australia, and Canada.10 A study looking at a small number of US nephrologists has shown they may have limited experience in caring for patients who forego dialysis and they are not comfortable offering conservative management over dialysis.10 Another small study from Sweden also showed that many nephrologists do not feel prepared for end-of-life care and conversations.11

Patients often rely on knowledgeable recommendations from medical experts. However, medical paternalism occurs when a physician makes decisions deemed to be in the patient’s best interest but are against the patient’s wishes or when the patient is unable to give their consent.12 Hard paternalism occurs when the patient is competent to make their own medical decisions, while soft paternalism occurs when a patient is not competent to make their own medical decisions.13

Patient autonomy is widely recognized as an ethical principle in medicine. It recognizes patients as well-informed decision makers who may act without excessive influence to make intentional determinations on their own behalf.14 Autonomy can be exercised at any point during the health care process.12 Although ethical and legal guidelines encourage physicians to recommend appropriate treatment, medical opinion cannot overrule the wishes of a competent patient who refuses treatment.12

Case Presentation

Mr. S presented to the emergency department at a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center with abdominal pain from recurrent pancreatitis. The patient aged > 65 years had a history of depression, ESRD, and was receiving hemodialysis. A computed tomography scan revealed a new pancreatic mass, and he was referred to the palliative care (PC) department nurse practitioner (NP) for a goals-of-care discussion. PC was informed to assist with hospice care initiation: The patient elected a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) code status and hospice care.

At the consultation, Mr. S stated that he had decided to forego life-prolonging treatments, including hemodialysis, and declined further evaluation for his pancreatic mass. He shared a good understanding of concerns for malignancy with his mass but did not wish to pursue further diagnostics as he knew his life expectancy was very limited without dialysis. He had been dependent on hemodialysis for the past 10 years. He had briefly received hospice care 5 years before but changed his mind and decided to pursue standard care, including life-prolonging dialysis treatments. He reported no depression, suicidal ideation, or intentions of hastening his death. He stated that he was just physically tired from his ongoing dialysis, recurrent hospitalizations, and being repeatedly subjected to diagnostic tests. Mr. S added that he had discussed his plan with his family, including his son and sister-in-law who is married to his brother. Mr. S previously identified his brother as his surrogate decision maker.

Mr. S shared that his brother had sustained a traumatic brain injury and was now unable to engage in a meaningful conversation. He shared that his family supported his decision. He also recognized that with his debility, he would need inpatient hospice care. On finding out that Mr. S’s brother was no longer able to act as the surrogate decision maker, the PC NP asked whether he wanted her to contact his son to share the outcome of their visit. The patient declined, adding that he had discussed his care plans with his family and did not feel that his health care team needed to have additional discussions with them.

Mr. S also reported chronic, recurrent right upper quadrant pain. He was prescribed oxycodone 10 mg every 4 hours as needed; however, it did little to control his pain. He also reported generalized pruritus, a complication of his renal failure.

After 1 week, Mr. S was transferred to the inpatient hospice unit. At that time, he allowed the hospice team to contact his son for medical updates and identified him as the primary point of contact for the hospice team if the need arose to reach his family. Due to the restrictions imposed by the pandemic, Mr. S had virtual video visits with his family. Mr. S developed intermittent confusion and worsening fatigue over time. His son was informed of his deteriorating condition and visited his father. Mr. S died peacefully 2 days later with his family present.

Multidisciplinary Inputs on the Case

Medicine. In discussing the case with medicine, the PC NP was informed that the goals the patient had for his care, which included stopping dialysis, having a DNR code status and pursuing hospice care, along with the patient’s pain symptoms prompted the PC consultation. The resident also shared concerns about the patient’s refusal to have his surrogate decision maker and family contacted regarding his decisions for his care.

Palliative care. After meeting with the patient and assisting in identifying goals for care, the PC NP recommended initiation of hospice care in the hospital while the patient awaited transfer to the inpatient hospice unit. The PC NP also recommended a psychiatric evaluation to rule out untreated depression that might influence the patient’s decision making. A follow-up visit with nephrology was also recommended. Optimal management of his distressing physical symptoms was recommended, including prescribing hydromorphone instead of oxycodone for his pain and starting a topical emollient for pruritus.

Nephrology. The patient’s electronic health records (EHR) showed that he informed nephrology of his desire to pursue hospice care and that he decided against further dialysis, including as-needed dialysis for comfort. The records also indicated that the patient understood the consequences of discontinuing dialysis.

Psychiatry. The patient’s EHR also showed that during his psychiatric visits, Mr. S reported he had no thoughts of suicide, and it was against his spiritual beliefs. He said he made his own medical decisions and expressed that his health care team should not attempt to change his mind. He also said he understood that stopping dialysis could lead to early death. He stated he had a close relationship with his family and discussed his medical decisions with them. He was tearful at times when he talked about his family. Mr. S shared his frustration about repeatedly being asked the same questions on succeeding visits.

After evaluation, psychiatry diagnosed Mr. S with mood disorder with depressive features and he was prescribed methylphenidate 5 mg daily and sertraline 25 mg daily. They also recommended continuing to offer dialysis in a supportive manner since the patient had changed his mind about hospice in the past. However, psychiatry followed the patient daily for 5 days and concluded that his medical decisions were not clouded by mood symptoms.

Discussion