User login

For MD-IQ use only

Lack of food for thought: Starve a bacterium, feed an infection

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

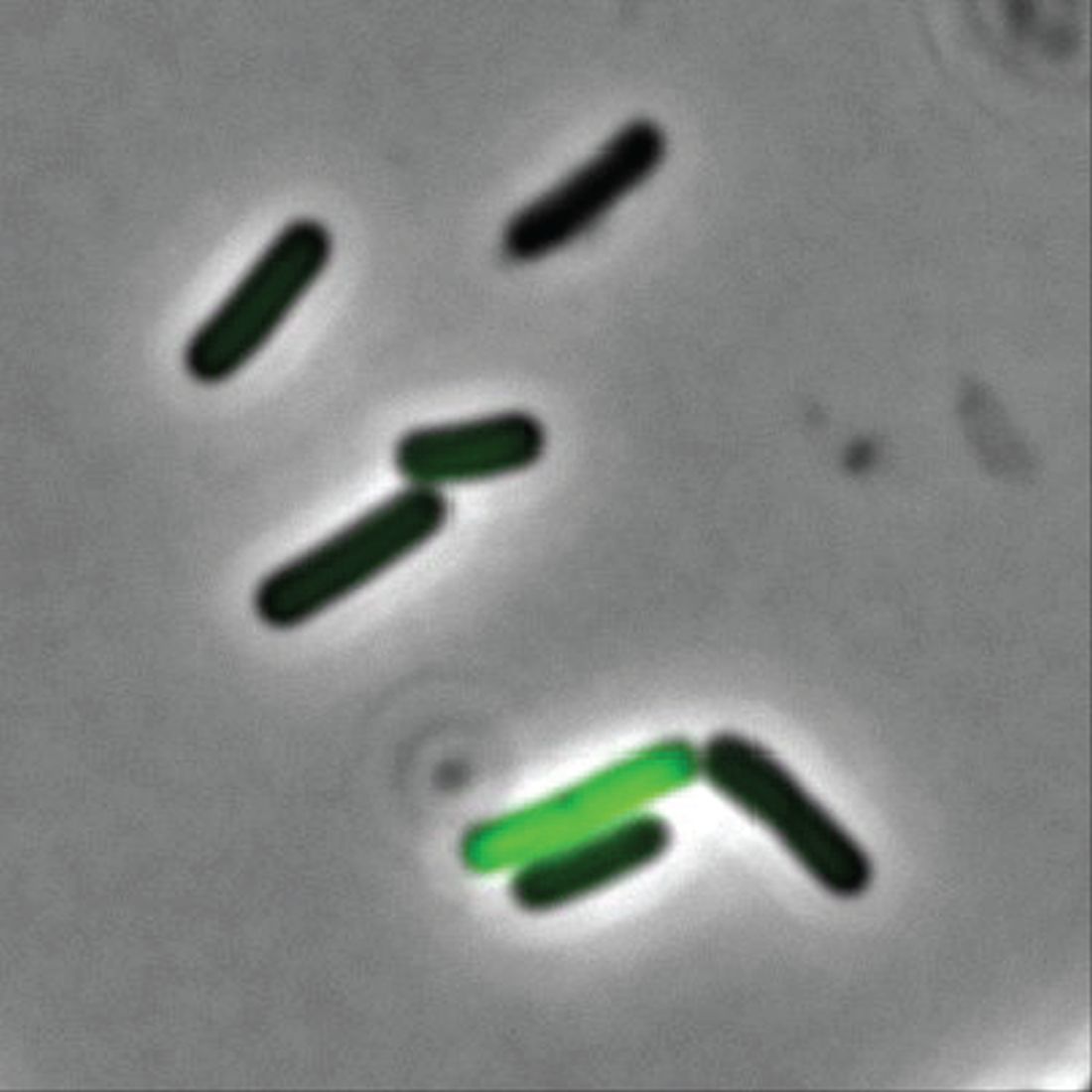

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

A whole new, tiny level of hangry

Ever been so hungry that everything just got on your nerves? Maybe you feel a little snappy right now? Like you’ll just lash out unless you get something to eat? Been there. And so have bacteria.

New research shows that some bacteria go into a full-on Hulk smash if they’re not getting the nutrients they need by releasing toxins into the body. Sounds like a bacterial temper tantrum.

Even though two cells may be genetically identical, they don’t always behave the same in a bacterial community. Some do their job and stay in line, but some evil twins rage out and make people sick by releasing toxins into the environment, Adam Rosenthal, PhD, of the University of North Carolina and his colleagues discovered.

To figure out why some cells were all business as usual while others were not, the investigators looked at Clostridium perfringens, a bacterium found in the intestines of humans and other vertebrates. When the C. perfringens cells were fed a little acetate to munch on, the hangry cells calmed down faster than a kid with a bag of fruit snacks, reducing toxin levels. Some cells even disappeared, falling in line with their model-citizen counterparts.

So what does this really mean? More research, duh. Now that we know nutrients play a role in toxicity, it may open the door to finding a way to fight against antibiotic resistance in humans and reduce antibiotic use in the food industry.

So think to yourself. Are you bothered for no reason? Getting a little testy with your friends and coworkers? Maybe you just haven’t eaten in a while. You’re literally not alone. Even a single-cell organism can behave based on its hunger levels.

Now go have a snack. Your bacteria are getting restless.

The very hangry iguana?

Imagine yourself on a warm, sunny tropical beach. You are enjoying a piece of cake as you take in the slow beat of the waves lapping against the shore. Life is as good as it could be.

Then you feel a presence nearby. Hostility. Hunger. A set of feral, covetous eyes in the nearby jungle. A reptilian beast stalks you, and its all-encompassing sweet tooth desires your cake.

Wait, hold on, what?

As an unfortunate 3-year-old on vacation in Costa Rica found out, there’s at least one iguana in the world out there with a taste for sugar (better than a taste for blood, we suppose).

While out on the beach, the lizard darted out of nowhere, bit the girl on the back of the hand, and stole her cake. Still not the worst party guest ever. The child was taken to a local clinic, where the wound was cleaned and a 5-day antibiotic treatment (lizards carry salmonella) was provided. Things seemed fine, and the girl returned home without incident.

But of course, that’s not the end of the story. Five months later, the girl’s parents noticed a red bump at the wound site. Over the next 3 months, the surrounding skin grew red and painful. A trip to the hospital in California revealed that she had a ganglion cyst and a discharge of pus. Turns out our cake-obsessed lizard friend did give the little girl a gift: the first known human case of Mycobacterium marinum infection following an iguana bite on record.

M. marinum, which causes a disease similar to tuberculosis, typically infects fish but can infect humans if skin wounds are exposed to contaminated water. It’s also resistant to most antibiotics, which is why the first round didn’t clear up the infection. A second round of more-potent antibiotics seems to be working well.

So, to sum up, this poor child got bitten by a lizard, had her cake stolen, and contracted a rare illness in exchange. For a 3-year-old, that’s gotta be in the top-10 worst days ever. Unless, of course, we’re actually living in the Marvel universe (sorry, multiverse at this point). Then we’re totally going to see the emergence of the new superhero Iguana Girl in 15 years or so. Keep your eyes open.

No allergies? Let them give up cake

Allergy season is already here – starting earlier every year, it seems – and many people are not happy about it. So unhappy, actually, that there’s a list of things they would be willing to give up for a year to get rid of their of allergies, according to a survey conducted by OnePoll on behalf of Flonase.

Nearly 40% of 2,000 respondents with allergies would go a year without eating cake or chocolate or playing video games in exchange for allergy-free status, the survey results show. Almost as many would forgo coffee (38%) or pizza (37%) for a year, while 36% would stay off social media and 31% would take a pay cut or give up their smartphones, the Independent reported.

More than half of the allergic Americans – 54%, to be exact – who were polled this past winter – Feb. 24 to March 1, to be exact – consider allergy symptoms to be the most frustrating part of the spring. Annoying things that were less frustrating to the group included mosquitoes (41%), filing tax returns (38%), and daylight savings time (37%).

The Trump arraignment circus, of course, occurred too late to make the list, as did the big “We’re going back to the office! No wait, we’re closing the office forever!” email extravaganza and emotional roller coaster. That second one, however, did not get nearly as much media coverage.

The sacrifice of orthodoxy: Maintaining collegiality in psychiatry

Psychiatrists practice in a wide array of ways. We approach our work and our patients with beliefs and preconceptions that develop over time. Our training has significant influence, though our own personalities and biases also affect our understanding.

Psychiatrists have philosophical lenses through which they see patients. We can reflect and see some standard archetypes. We are familiar with the reductionistic pharmacologist, the somatic treatment specialist, the psychodynamic ‘guru,’ and the medicolegally paralyzed practitioner. It is without judgment that we lay these out, for our very point is that we have these constituent parts within our own clinical identities. The intensity with which we subscribe to these clinical sensibilities could contribute to a biased orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy can be defined as an accepted theory that stems from an authoritative entity. This is a well-known phenomenon that continues to be visible. For example, one can quickly peruse psychodynamic literature to find one school of thought criticizing another. It is not without some confrontation and even interpersonal rifts that the lineage of psychoanalytic theory has evolved. This has always been of interest to us. A core facet of psychoanalysis is empathy, truly knowing the inner state of a different person. And yet, the very bastions of this clinical sensibility frequently resort to veiled attacks on those in their field who have opposing views. It then begs the question: If even enlightened institutions fail at a nonjudgmental approach toward their colleagues, what hope is there for the rest of us clinicians, mired in the thick of day-to-day clinical practice?

It is our contention that the odds are against us. Even the aforementioned critique of psychoanalytic orthodoxy is just another example of how we humans organize our experience. Even as we write an article in argument against unbridled critique, we find it difficult to do so without engaging in it. For to criticize another is to help shore up our own personal identities. This is especially the case when clinicians deal with issues that we feel strongly about. The human psyche has a need to organize its experience, as “our experience of ourselves is fundamental to how we operate in the world. Our subjective experience is the phenomenology of all that one might be aware of.”1

In this vein, we would like to cite attribution theory. This is a view of human behavior within social psychology. The Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider, PhD, investigated “the domain of social interactions, wondering how people perceive each other in interaction and especially how they make sense of each other’s behavior.”2 Attribution theory suggests that as humans organize our social interactions, we may make two basic assumptions. One is that our own behavior is highly affected by an environment that is beyond our control. The second is that when judging the behavior of others, we are more likely to attribute it to internal traits that they have. A classic example is automobile traffic. When we see someone driving erratically, we are more likely to blame them for being an inherently bad driver. However, if attention is called to our own driving, we are more likely to cite external factors such as rush hour, a bad driver around us, or a faulty vehicle.

We would like to reference one last model of human behavior. It has become customary within the field of neuroscience to view the brain as a predictive organ: “Theories of prediction in perception, action, and learning suggest that the brain serves to reduce the discrepancies between expectation and actual experience, i.e., by reducing the prediction error.”3 Perception itself has recently been described as a controlled hallucination, where the brain makes predictions of what it thinks it is about to see based on past experiences. Visual stimulus ultimately takes time to enter our eyes and be processed in the brain – “predictions would need to preactivate neural representations that would typically be driven by sensory input, before the actual arrival of that input.”4 It thus seems to be an inherent method of the brain to anticipate visual and even social events to help human beings sustain themselves.

Having spoken of a psychoanalytic conceptualization of self-organization, the theory of attribution, and research into social neuroscience, we turn our attention back to the central question that this article would like to address.

When we find ourselves busy in rote clinical practice, we believe the likelihood of intercollegiate mentalization is low; our ability to relate to our peers becomes strained. We ultimately do not practice in a vacuum. Psychiatrists, even those in a solo private practice, are ultimately part of a community of providers who, more or less, follow some emergent ‘standard of care.’ This can be a vague concept; but one that takes on a concrete form in the minds of certain clinicians and certainly in the setting of a medicolegal court. Yet, the psychiatrists that we know all have very stereotyped ways of practice. And at the heart of it, we all think that we are right.

We can use polypharmacy as an example. Imagine that you have a new patient intake, who tells you that they are transferring care from another psychiatrist. They inform you of their medication regimen. This patient presents on eight or more psychotropics. Many of us may have a visceral reaction at this point and, following the aforementioned attribution theory, we may ask ourselves what ‘quack’ of a doctor would do this. Yet some among us would think that a very competent psychopharmacologist was daring enough to use the full armamentarium of psychopharmacology to help this patient, who must be treatment refractory.

When speaking with such a patient, we would be quick to reflect on our own parsimonious use of medications. We would tell ourselves that we are responsible providers and would be quick to recommend discontinuation of medications. This would help us feel better about ourselves, and would of course assuage the ever-present medicolegal ‘big brother’ in our minds. It is through this very process that we affirm our self-identities. For if this patient’s previous physician was a bad psychiatrist, then we are a good psychiatrist. It is through this process that our clinical selves find confirmation.

We do not mean to reduce the complexities of human behavior to quick stereotypes. However, it is our belief that when confronted with clinical or philosophical disputes with our colleagues, the basic rules of human behavior will attempt to dissolve and override efforts at mentalization, collegiality, or interpersonal sensitivity. For to accept a clinical practice view that is different from ours would be akin to giving up the essence of our clinical identities. It could be compared to the fragmentation process of a vulnerable psyche when confronted with a reality that is at odds with preconceived notions and experiences.

While we may be able to appreciate the nuances and sensibilities of another provider, we believe it would be particularly difficult for most of us to actually attempt to practice in a fashion that is not congruent with our own organizers of experience. Whether or not our practice style is ‘perfect,’ it has worked for us. Social neuroscience and our understanding of the organization of the self would predict that we would hold onto our way of practice with all the mind’s defenses. Externalization, denial, and projection could all be called into action in this battle against existential fragmentation.

Do we seek to portray a clinical world where there is no hope for genuine modeling of clinical sensibilities to other psychiatrists? That is not our intention. Yet it seems that many of the theoretical frameworks that we subscribe to argue against this possibility. We would be hypocritical if we did not here state that our own theoretical frameworks are yet other examples of “organizers of experience.” Attribution theory, intersubjectivity, and social neuroscience are simply our ways of organizing the chaos of perceptions, ideas, and intricacies of human behavior.

If we accept that psychiatrists, like all human beings, are trapped in a subjective experience, then we can be more playful and flexible when interacting with our colleagues. We do not have to be as defensive of our practices and accusatory of others. If we practice daily according to some orthodoxy, then we color our experiences of the patient and of our colleagues’ ways of practice. We automatically start off on the wrong foot. And yet, to give up this orthodoxy would, by definition, be disorganizing and fragmenting to us. For as Nietzsche said, “truth is an illusion without which a certain species could not survive.”5

Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Buirski P and Haglund P. Making sense together: The intersubjective approach to psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2001.

2. Malle BF. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee D (ed.), Theories in social psychology. pp. 72-95. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

3. Brown EC and Brune M. The role of prediction in social neuroscience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 May 24;6:147. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00147.

4. Blom T et al. Predictions drive neural representations of visual events ahead of incoming sensory information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020 Mar 31;117(13):7510-7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917777117.

5. Yalom I. The Gift of Therapy. Harper Perennial; 2002.

Psychiatrists practice in a wide array of ways. We approach our work and our patients with beliefs and preconceptions that develop over time. Our training has significant influence, though our own personalities and biases also affect our understanding.

Psychiatrists have philosophical lenses through which they see patients. We can reflect and see some standard archetypes. We are familiar with the reductionistic pharmacologist, the somatic treatment specialist, the psychodynamic ‘guru,’ and the medicolegally paralyzed practitioner. It is without judgment that we lay these out, for our very point is that we have these constituent parts within our own clinical identities. The intensity with which we subscribe to these clinical sensibilities could contribute to a biased orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy can be defined as an accepted theory that stems from an authoritative entity. This is a well-known phenomenon that continues to be visible. For example, one can quickly peruse psychodynamic literature to find one school of thought criticizing another. It is not without some confrontation and even interpersonal rifts that the lineage of psychoanalytic theory has evolved. This has always been of interest to us. A core facet of psychoanalysis is empathy, truly knowing the inner state of a different person. And yet, the very bastions of this clinical sensibility frequently resort to veiled attacks on those in their field who have opposing views. It then begs the question: If even enlightened institutions fail at a nonjudgmental approach toward their colleagues, what hope is there for the rest of us clinicians, mired in the thick of day-to-day clinical practice?

It is our contention that the odds are against us. Even the aforementioned critique of psychoanalytic orthodoxy is just another example of how we humans organize our experience. Even as we write an article in argument against unbridled critique, we find it difficult to do so without engaging in it. For to criticize another is to help shore up our own personal identities. This is especially the case when clinicians deal with issues that we feel strongly about. The human psyche has a need to organize its experience, as “our experience of ourselves is fundamental to how we operate in the world. Our subjective experience is the phenomenology of all that one might be aware of.”1

In this vein, we would like to cite attribution theory. This is a view of human behavior within social psychology. The Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider, PhD, investigated “the domain of social interactions, wondering how people perceive each other in interaction and especially how they make sense of each other’s behavior.”2 Attribution theory suggests that as humans organize our social interactions, we may make two basic assumptions. One is that our own behavior is highly affected by an environment that is beyond our control. The second is that when judging the behavior of others, we are more likely to attribute it to internal traits that they have. A classic example is automobile traffic. When we see someone driving erratically, we are more likely to blame them for being an inherently bad driver. However, if attention is called to our own driving, we are more likely to cite external factors such as rush hour, a bad driver around us, or a faulty vehicle.

We would like to reference one last model of human behavior. It has become customary within the field of neuroscience to view the brain as a predictive organ: “Theories of prediction in perception, action, and learning suggest that the brain serves to reduce the discrepancies between expectation and actual experience, i.e., by reducing the prediction error.”3 Perception itself has recently been described as a controlled hallucination, where the brain makes predictions of what it thinks it is about to see based on past experiences. Visual stimulus ultimately takes time to enter our eyes and be processed in the brain – “predictions would need to preactivate neural representations that would typically be driven by sensory input, before the actual arrival of that input.”4 It thus seems to be an inherent method of the brain to anticipate visual and even social events to help human beings sustain themselves.

Having spoken of a psychoanalytic conceptualization of self-organization, the theory of attribution, and research into social neuroscience, we turn our attention back to the central question that this article would like to address.

When we find ourselves busy in rote clinical practice, we believe the likelihood of intercollegiate mentalization is low; our ability to relate to our peers becomes strained. We ultimately do not practice in a vacuum. Psychiatrists, even those in a solo private practice, are ultimately part of a community of providers who, more or less, follow some emergent ‘standard of care.’ This can be a vague concept; but one that takes on a concrete form in the minds of certain clinicians and certainly in the setting of a medicolegal court. Yet, the psychiatrists that we know all have very stereotyped ways of practice. And at the heart of it, we all think that we are right.

We can use polypharmacy as an example. Imagine that you have a new patient intake, who tells you that they are transferring care from another psychiatrist. They inform you of their medication regimen. This patient presents on eight or more psychotropics. Many of us may have a visceral reaction at this point and, following the aforementioned attribution theory, we may ask ourselves what ‘quack’ of a doctor would do this. Yet some among us would think that a very competent psychopharmacologist was daring enough to use the full armamentarium of psychopharmacology to help this patient, who must be treatment refractory.

When speaking with such a patient, we would be quick to reflect on our own parsimonious use of medications. We would tell ourselves that we are responsible providers and would be quick to recommend discontinuation of medications. This would help us feel better about ourselves, and would of course assuage the ever-present medicolegal ‘big brother’ in our minds. It is through this very process that we affirm our self-identities. For if this patient’s previous physician was a bad psychiatrist, then we are a good psychiatrist. It is through this process that our clinical selves find confirmation.

We do not mean to reduce the complexities of human behavior to quick stereotypes. However, it is our belief that when confronted with clinical or philosophical disputes with our colleagues, the basic rules of human behavior will attempt to dissolve and override efforts at mentalization, collegiality, or interpersonal sensitivity. For to accept a clinical practice view that is different from ours would be akin to giving up the essence of our clinical identities. It could be compared to the fragmentation process of a vulnerable psyche when confronted with a reality that is at odds with preconceived notions and experiences.

While we may be able to appreciate the nuances and sensibilities of another provider, we believe it would be particularly difficult for most of us to actually attempt to practice in a fashion that is not congruent with our own organizers of experience. Whether or not our practice style is ‘perfect,’ it has worked for us. Social neuroscience and our understanding of the organization of the self would predict that we would hold onto our way of practice with all the mind’s defenses. Externalization, denial, and projection could all be called into action in this battle against existential fragmentation.

Do we seek to portray a clinical world where there is no hope for genuine modeling of clinical sensibilities to other psychiatrists? That is not our intention. Yet it seems that many of the theoretical frameworks that we subscribe to argue against this possibility. We would be hypocritical if we did not here state that our own theoretical frameworks are yet other examples of “organizers of experience.” Attribution theory, intersubjectivity, and social neuroscience are simply our ways of organizing the chaos of perceptions, ideas, and intricacies of human behavior.

If we accept that psychiatrists, like all human beings, are trapped in a subjective experience, then we can be more playful and flexible when interacting with our colleagues. We do not have to be as defensive of our practices and accusatory of others. If we practice daily according to some orthodoxy, then we color our experiences of the patient and of our colleagues’ ways of practice. We automatically start off on the wrong foot. And yet, to give up this orthodoxy would, by definition, be disorganizing and fragmenting to us. For as Nietzsche said, “truth is an illusion without which a certain species could not survive.”5

Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Buirski P and Haglund P. Making sense together: The intersubjective approach to psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2001.

2. Malle BF. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee D (ed.), Theories in social psychology. pp. 72-95. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

3. Brown EC and Brune M. The role of prediction in social neuroscience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 May 24;6:147. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00147.

4. Blom T et al. Predictions drive neural representations of visual events ahead of incoming sensory information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020 Mar 31;117(13):7510-7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917777117.

5. Yalom I. The Gift of Therapy. Harper Perennial; 2002.

Psychiatrists practice in a wide array of ways. We approach our work and our patients with beliefs and preconceptions that develop over time. Our training has significant influence, though our own personalities and biases also affect our understanding.

Psychiatrists have philosophical lenses through which they see patients. We can reflect and see some standard archetypes. We are familiar with the reductionistic pharmacologist, the somatic treatment specialist, the psychodynamic ‘guru,’ and the medicolegally paralyzed practitioner. It is without judgment that we lay these out, for our very point is that we have these constituent parts within our own clinical identities. The intensity with which we subscribe to these clinical sensibilities could contribute to a biased orthodoxy.

Orthodoxy can be defined as an accepted theory that stems from an authoritative entity. This is a well-known phenomenon that continues to be visible. For example, one can quickly peruse psychodynamic literature to find one school of thought criticizing another. It is not without some confrontation and even interpersonal rifts that the lineage of psychoanalytic theory has evolved. This has always been of interest to us. A core facet of psychoanalysis is empathy, truly knowing the inner state of a different person. And yet, the very bastions of this clinical sensibility frequently resort to veiled attacks on those in their field who have opposing views. It then begs the question: If even enlightened institutions fail at a nonjudgmental approach toward their colleagues, what hope is there for the rest of us clinicians, mired in the thick of day-to-day clinical practice?

It is our contention that the odds are against us. Even the aforementioned critique of psychoanalytic orthodoxy is just another example of how we humans organize our experience. Even as we write an article in argument against unbridled critique, we find it difficult to do so without engaging in it. For to criticize another is to help shore up our own personal identities. This is especially the case when clinicians deal with issues that we feel strongly about. The human psyche has a need to organize its experience, as “our experience of ourselves is fundamental to how we operate in the world. Our subjective experience is the phenomenology of all that one might be aware of.”1

In this vein, we would like to cite attribution theory. This is a view of human behavior within social psychology. The Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider, PhD, investigated “the domain of social interactions, wondering how people perceive each other in interaction and especially how they make sense of each other’s behavior.”2 Attribution theory suggests that as humans organize our social interactions, we may make two basic assumptions. One is that our own behavior is highly affected by an environment that is beyond our control. The second is that when judging the behavior of others, we are more likely to attribute it to internal traits that they have. A classic example is automobile traffic. When we see someone driving erratically, we are more likely to blame them for being an inherently bad driver. However, if attention is called to our own driving, we are more likely to cite external factors such as rush hour, a bad driver around us, or a faulty vehicle.

We would like to reference one last model of human behavior. It has become customary within the field of neuroscience to view the brain as a predictive organ: “Theories of prediction in perception, action, and learning suggest that the brain serves to reduce the discrepancies between expectation and actual experience, i.e., by reducing the prediction error.”3 Perception itself has recently been described as a controlled hallucination, where the brain makes predictions of what it thinks it is about to see based on past experiences. Visual stimulus ultimately takes time to enter our eyes and be processed in the brain – “predictions would need to preactivate neural representations that would typically be driven by sensory input, before the actual arrival of that input.”4 It thus seems to be an inherent method of the brain to anticipate visual and even social events to help human beings sustain themselves.

Having spoken of a psychoanalytic conceptualization of self-organization, the theory of attribution, and research into social neuroscience, we turn our attention back to the central question that this article would like to address.

When we find ourselves busy in rote clinical practice, we believe the likelihood of intercollegiate mentalization is low; our ability to relate to our peers becomes strained. We ultimately do not practice in a vacuum. Psychiatrists, even those in a solo private practice, are ultimately part of a community of providers who, more or less, follow some emergent ‘standard of care.’ This can be a vague concept; but one that takes on a concrete form in the minds of certain clinicians and certainly in the setting of a medicolegal court. Yet, the psychiatrists that we know all have very stereotyped ways of practice. And at the heart of it, we all think that we are right.

We can use polypharmacy as an example. Imagine that you have a new patient intake, who tells you that they are transferring care from another psychiatrist. They inform you of their medication regimen. This patient presents on eight or more psychotropics. Many of us may have a visceral reaction at this point and, following the aforementioned attribution theory, we may ask ourselves what ‘quack’ of a doctor would do this. Yet some among us would think that a very competent psychopharmacologist was daring enough to use the full armamentarium of psychopharmacology to help this patient, who must be treatment refractory.

When speaking with such a patient, we would be quick to reflect on our own parsimonious use of medications. We would tell ourselves that we are responsible providers and would be quick to recommend discontinuation of medications. This would help us feel better about ourselves, and would of course assuage the ever-present medicolegal ‘big brother’ in our minds. It is through this very process that we affirm our self-identities. For if this patient’s previous physician was a bad psychiatrist, then we are a good psychiatrist. It is through this process that our clinical selves find confirmation.

We do not mean to reduce the complexities of human behavior to quick stereotypes. However, it is our belief that when confronted with clinical or philosophical disputes with our colleagues, the basic rules of human behavior will attempt to dissolve and override efforts at mentalization, collegiality, or interpersonal sensitivity. For to accept a clinical practice view that is different from ours would be akin to giving up the essence of our clinical identities. It could be compared to the fragmentation process of a vulnerable psyche when confronted with a reality that is at odds with preconceived notions and experiences.

While we may be able to appreciate the nuances and sensibilities of another provider, we believe it would be particularly difficult for most of us to actually attempt to practice in a fashion that is not congruent with our own organizers of experience. Whether or not our practice style is ‘perfect,’ it has worked for us. Social neuroscience and our understanding of the organization of the self would predict that we would hold onto our way of practice with all the mind’s defenses. Externalization, denial, and projection could all be called into action in this battle against existential fragmentation.

Do we seek to portray a clinical world where there is no hope for genuine modeling of clinical sensibilities to other psychiatrists? That is not our intention. Yet it seems that many of the theoretical frameworks that we subscribe to argue against this possibility. We would be hypocritical if we did not here state that our own theoretical frameworks are yet other examples of “organizers of experience.” Attribution theory, intersubjectivity, and social neuroscience are simply our ways of organizing the chaos of perceptions, ideas, and intricacies of human behavior.

If we accept that psychiatrists, like all human beings, are trapped in a subjective experience, then we can be more playful and flexible when interacting with our colleagues. We do not have to be as defensive of our practices and accusatory of others. If we practice daily according to some orthodoxy, then we color our experiences of the patient and of our colleagues’ ways of practice. We automatically start off on the wrong foot. And yet, to give up this orthodoxy would, by definition, be disorganizing and fragmenting to us. For as Nietzsche said, “truth is an illusion without which a certain species could not survive.”5

Dr. Khalafian practices full time as a general outpatient psychiatrist. He trained at the University of California, San Diego, for his psychiatric residency and currently works as a telepsychiatrist, serving an outpatient clinic population in northern California. Dr. Badre is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in San Diego. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Dr. Badre can be reached at his website, BadreMD.com. Dr. Badre and Dr. Khalafian have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Buirski P and Haglund P. Making sense together: The intersubjective approach to psychotherapy. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 2001.

2. Malle BF. Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior. In Chadee D (ed.), Theories in social psychology. pp. 72-95. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

3. Brown EC and Brune M. The role of prediction in social neuroscience. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012 May 24;6:147. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00147.

4. Blom T et al. Predictions drive neural representations of visual events ahead of incoming sensory information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020 Mar 31;117(13):7510-7515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917777117.

5. Yalom I. The Gift of Therapy. Harper Perennial; 2002.

Deadly bacteria in recalled eye drops can spread person-to-person

according to a new report.

Scientists are concerned that the once-rare treatment-resistant bacteria found in the eyedrops can spread person-to-person, posing a risk of becoming a recurrent problem in the United States, The New York Times reported.

In January, EzriCare and Delsam Pharma artificial tears and ointment products were recalled after being linked to the bacterium P. aeruginosa. The bacteria have caused at least 68 infections, including three deaths and at least eight cases of blindness. The eyedrops were imported to the United States from India, and many of the cases occurred after the bacteria spread person-to-person at a long-term care facility in Connecticut, according to the Times, which cited FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lead investigator Maroya Walters, PhD.

Dr. Walters said the cases that caused death or blindness were traced to the EzriCare artificial tears product.

“It’s very hard to get rid of,” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill infectious disease specialist David van Duin, MD, PhD, told the Times, noting that the bacteria cling to sink drains, water faucets, and other moist places.

The FDA said it had halted the import of the recalled products and has since visited the plant in India where they were made, which is owned by Global Pharma Healthcare. In a citation to the company dated March 2, the FDA listed nearly a dozen problems, such as dirty equipment and the absence of safety procedures and tests.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new report.

Scientists are concerned that the once-rare treatment-resistant bacteria found in the eyedrops can spread person-to-person, posing a risk of becoming a recurrent problem in the United States, The New York Times reported.

In January, EzriCare and Delsam Pharma artificial tears and ointment products were recalled after being linked to the bacterium P. aeruginosa. The bacteria have caused at least 68 infections, including three deaths and at least eight cases of blindness. The eyedrops were imported to the United States from India, and many of the cases occurred after the bacteria spread person-to-person at a long-term care facility in Connecticut, according to the Times, which cited FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lead investigator Maroya Walters, PhD.

Dr. Walters said the cases that caused death or blindness were traced to the EzriCare artificial tears product.

“It’s very hard to get rid of,” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill infectious disease specialist David van Duin, MD, PhD, told the Times, noting that the bacteria cling to sink drains, water faucets, and other moist places.

The FDA said it had halted the import of the recalled products and has since visited the plant in India where they were made, which is owned by Global Pharma Healthcare. In a citation to the company dated March 2, the FDA listed nearly a dozen problems, such as dirty equipment and the absence of safety procedures and tests.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new report.

Scientists are concerned that the once-rare treatment-resistant bacteria found in the eyedrops can spread person-to-person, posing a risk of becoming a recurrent problem in the United States, The New York Times reported.

In January, EzriCare and Delsam Pharma artificial tears and ointment products were recalled after being linked to the bacterium P. aeruginosa. The bacteria have caused at least 68 infections, including three deaths and at least eight cases of blindness. The eyedrops were imported to the United States from India, and many of the cases occurred after the bacteria spread person-to-person at a long-term care facility in Connecticut, according to the Times, which cited FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lead investigator Maroya Walters, PhD.

Dr. Walters said the cases that caused death or blindness were traced to the EzriCare artificial tears product.

“It’s very hard to get rid of,” University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill infectious disease specialist David van Duin, MD, PhD, told the Times, noting that the bacteria cling to sink drains, water faucets, and other moist places.

The FDA said it had halted the import of the recalled products and has since visited the plant in India where they were made, which is owned by Global Pharma Healthcare. In a citation to the company dated March 2, the FDA listed nearly a dozen problems, such as dirty equipment and the absence of safety procedures and tests.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The end of the telemedicine era?

I started taking care of Jim, a 68-year-old man with metastatic renal cell carcinoma back in the fall of 2018. Jim lived far from our clinic in the rural western Sierra Mountains and had a hard time getting to Santa Monica, but needed ongoing pain and symptom management, as well as follow-up visits with oncology and discussions with our teams about preparing for the end of life.

Luckily for Jim, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had relaxed the rules around telehealth because of the public health emergency, and we were easily able to provide telemedicine visits throughout the pandemic ensuring that Jim retained access to the care team that had managed his cancer for several years at that point. This would not have been possible without the use of telemedicine – at least not without great effort and expense by Jim to make frequent trips to our Santa Monica clinic.

So, you can imagine my apprehension when I received an email the other day from our billing department, informing billing providers like myself that “telehealth visits are still covered through the end of the year.” While this initially seemed like reassuring news, it immediately begged the question – what happens at the end of the year? What will care look like for patients like Jim who live at a significant distance from their providers?

The end of the COVID-19 public health emergency on May 11 has prompted states to reevaluate the future of telehealth for Medicaid and Medicare recipients. Most states plan to make some telehealth services permanent, particularly in rural areas. While other telehealth services have been extended through Dec. 31, 2024, under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023.

But still, We can now see very ill patients in their own homes without imposing an undue burden on them to come in for yet another office visit. Prior to the public health emergency, our embedded palliative care program would see patients only when they were in the oncology clinic so as to not burden them with having to travel to yet another clinic. This made our palliative providers less efficient since patients were being seen by multiple providers in the same space, which led to some time spent waiting around. It also frequently tied up our clinic exam rooms for long periods of time, delaying care for patients sitting in the waiting room.

Telehealth changed that virtually overnight. With the widespread availability of smartphones and tablets, patients could stay at home and speak more comfortably in their own surroundings – especially about the difficult topics we tend to dig into in palliative care – such as fears, suffering, grief, loss, legacy, regret, trauma, gratitude, dying – without the impersonal, aseptic environment of a clinic. We could visit with their family/caregivers, kids, and their pets. We could tour their living space and see how they were managing from a functional standpoint. We could get to know aspects of our patients’ lives that we’d never have seen in the clinic that could help us understand their goals and values better and help care for them more fully.

The benefit to the institution was also measurable. We could see our patients faster – the time from referral to consult dropped dramatically because patients could be scheduled for next-day virtual visits instead of having to wait for them to come back to an oncology visit. We could do quick symptom-focused visits that prior to telehealth would have been conducted by phone without the ability to perform at the very least an observational physical exam of the patient, which is important when prescribing medications to medically frail populations.

If telemedicine goes, how will it affect outpatient palliative care?

If that goes away, I do not know what will happen to outpatient palliative care. I can tell you we will be much less efficient in terms of when we see patients. There will probably be a higher clinic burden to patients, as well as higher financial toxicity to patients (Parking in the structure attached to my office building is $22 per day). And, what about the uncaptured costs associated with transportation for those whose illness prevents them from driving themselves? This can range from Uber costs to the time cost for a patient’s family member to take off work and arrange for childcare in order to drive the patient to a clinic for a visit.

In February, I received emails from the Drug Enforcement Agency suggesting that they, too, may roll back providers’ ability to prescribe controlled substances to patients who are mainly receiving telehealth services. While I understand and fully support the need to curb inappropriate overprescribing of controlled medications, I am concerned about the unintended consequences to cancer patients who live at a remote distance from their oncologists and palliative care providers. I remain hopeful that DEA will consider a carveout exception for those patients who have cancer, are receiving palliative care services, or are deemed to be at the end of life, much like the chronic opioid guidelines developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have done.

Telemedicine in essential care

Back to Jim. Using telehealth and electronic prescribing, our oncology and palliative care programs were able to keep Jim comfortable and at home through the end of his life. He did not have to travel 3 hours each way to get care. He did not have to spend money on parking and gas, and his daughter did not have to take days off work and arrange for a babysitter in order to drive him to our clinic. We partnered with a local pharmacy that was willing to special order medications for Jim when his pain became worse and he required a long-acting opioid. We partnered with a local home health company that kept a close eye on Jim and let us know when he seemed to be declining further, prompting discussions about transitioning to hospice.

I’m proud of the fact that our group helped Jim stay in comfortable surroundings and out of the clinic and hospital over the last 6 months of his life, but that would never have happened without the safe and thoughtful use of telehealth by our team.

Ironically, because of a public health emergency, we were able to provide efficient and high-quality palliative care at the right time, to the right person, in the right place, satisfying CMS goals to provide better care for patients and whole populations at lower costs.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

I started taking care of Jim, a 68-year-old man with metastatic renal cell carcinoma back in the fall of 2018. Jim lived far from our clinic in the rural western Sierra Mountains and had a hard time getting to Santa Monica, but needed ongoing pain and symptom management, as well as follow-up visits with oncology and discussions with our teams about preparing for the end of life.

Luckily for Jim, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had relaxed the rules around telehealth because of the public health emergency, and we were easily able to provide telemedicine visits throughout the pandemic ensuring that Jim retained access to the care team that had managed his cancer for several years at that point. This would not have been possible without the use of telemedicine – at least not without great effort and expense by Jim to make frequent trips to our Santa Monica clinic.

So, you can imagine my apprehension when I received an email the other day from our billing department, informing billing providers like myself that “telehealth visits are still covered through the end of the year.” While this initially seemed like reassuring news, it immediately begged the question – what happens at the end of the year? What will care look like for patients like Jim who live at a significant distance from their providers?

The end of the COVID-19 public health emergency on May 11 has prompted states to reevaluate the future of telehealth for Medicaid and Medicare recipients. Most states plan to make some telehealth services permanent, particularly in rural areas. While other telehealth services have been extended through Dec. 31, 2024, under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023.

But still, We can now see very ill patients in their own homes without imposing an undue burden on them to come in for yet another office visit. Prior to the public health emergency, our embedded palliative care program would see patients only when they were in the oncology clinic so as to not burden them with having to travel to yet another clinic. This made our palliative providers less efficient since patients were being seen by multiple providers in the same space, which led to some time spent waiting around. It also frequently tied up our clinic exam rooms for long periods of time, delaying care for patients sitting in the waiting room.

Telehealth changed that virtually overnight. With the widespread availability of smartphones and tablets, patients could stay at home and speak more comfortably in their own surroundings – especially about the difficult topics we tend to dig into in palliative care – such as fears, suffering, grief, loss, legacy, regret, trauma, gratitude, dying – without the impersonal, aseptic environment of a clinic. We could visit with their family/caregivers, kids, and their pets. We could tour their living space and see how they were managing from a functional standpoint. We could get to know aspects of our patients’ lives that we’d never have seen in the clinic that could help us understand their goals and values better and help care for them more fully.

The benefit to the institution was also measurable. We could see our patients faster – the time from referral to consult dropped dramatically because patients could be scheduled for next-day virtual visits instead of having to wait for them to come back to an oncology visit. We could do quick symptom-focused visits that prior to telehealth would have been conducted by phone without the ability to perform at the very least an observational physical exam of the patient, which is important when prescribing medications to medically frail populations.

If telemedicine goes, how will it affect outpatient palliative care?

If that goes away, I do not know what will happen to outpatient palliative care. I can tell you we will be much less efficient in terms of when we see patients. There will probably be a higher clinic burden to patients, as well as higher financial toxicity to patients (Parking in the structure attached to my office building is $22 per day). And, what about the uncaptured costs associated with transportation for those whose illness prevents them from driving themselves? This can range from Uber costs to the time cost for a patient’s family member to take off work and arrange for childcare in order to drive the patient to a clinic for a visit.

In February, I received emails from the Drug Enforcement Agency suggesting that they, too, may roll back providers’ ability to prescribe controlled substances to patients who are mainly receiving telehealth services. While I understand and fully support the need to curb inappropriate overprescribing of controlled medications, I am concerned about the unintended consequences to cancer patients who live at a remote distance from their oncologists and palliative care providers. I remain hopeful that DEA will consider a carveout exception for those patients who have cancer, are receiving palliative care services, or are deemed to be at the end of life, much like the chronic opioid guidelines developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have done.

Telemedicine in essential care

Back to Jim. Using telehealth and electronic prescribing, our oncology and palliative care programs were able to keep Jim comfortable and at home through the end of his life. He did not have to travel 3 hours each way to get care. He did not have to spend money on parking and gas, and his daughter did not have to take days off work and arrange for a babysitter in order to drive him to our clinic. We partnered with a local pharmacy that was willing to special order medications for Jim when his pain became worse and he required a long-acting opioid. We partnered with a local home health company that kept a close eye on Jim and let us know when he seemed to be declining further, prompting discussions about transitioning to hospice.

I’m proud of the fact that our group helped Jim stay in comfortable surroundings and out of the clinic and hospital over the last 6 months of his life, but that would never have happened without the safe and thoughtful use of telehealth by our team.

Ironically, because of a public health emergency, we were able to provide efficient and high-quality palliative care at the right time, to the right person, in the right place, satisfying CMS goals to provide better care for patients and whole populations at lower costs.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

I started taking care of Jim, a 68-year-old man with metastatic renal cell carcinoma back in the fall of 2018. Jim lived far from our clinic in the rural western Sierra Mountains and had a hard time getting to Santa Monica, but needed ongoing pain and symptom management, as well as follow-up visits with oncology and discussions with our teams about preparing for the end of life.

Luckily for Jim, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services had relaxed the rules around telehealth because of the public health emergency, and we were easily able to provide telemedicine visits throughout the pandemic ensuring that Jim retained access to the care team that had managed his cancer for several years at that point. This would not have been possible without the use of telemedicine – at least not without great effort and expense by Jim to make frequent trips to our Santa Monica clinic.

So, you can imagine my apprehension when I received an email the other day from our billing department, informing billing providers like myself that “telehealth visits are still covered through the end of the year.” While this initially seemed like reassuring news, it immediately begged the question – what happens at the end of the year? What will care look like for patients like Jim who live at a significant distance from their providers?

The end of the COVID-19 public health emergency on May 11 has prompted states to reevaluate the future of telehealth for Medicaid and Medicare recipients. Most states plan to make some telehealth services permanent, particularly in rural areas. While other telehealth services have been extended through Dec. 31, 2024, under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023.

But still, We can now see very ill patients in their own homes without imposing an undue burden on them to come in for yet another office visit. Prior to the public health emergency, our embedded palliative care program would see patients only when they were in the oncology clinic so as to not burden them with having to travel to yet another clinic. This made our palliative providers less efficient since patients were being seen by multiple providers in the same space, which led to some time spent waiting around. It also frequently tied up our clinic exam rooms for long periods of time, delaying care for patients sitting in the waiting room.

Telehealth changed that virtually overnight. With the widespread availability of smartphones and tablets, patients could stay at home and speak more comfortably in their own surroundings – especially about the difficult topics we tend to dig into in palliative care – such as fears, suffering, grief, loss, legacy, regret, trauma, gratitude, dying – without the impersonal, aseptic environment of a clinic. We could visit with their family/caregivers, kids, and their pets. We could tour their living space and see how they were managing from a functional standpoint. We could get to know aspects of our patients’ lives that we’d never have seen in the clinic that could help us understand their goals and values better and help care for them more fully.

The benefit to the institution was also measurable. We could see our patients faster – the time from referral to consult dropped dramatically because patients could be scheduled for next-day virtual visits instead of having to wait for them to come back to an oncology visit. We could do quick symptom-focused visits that prior to telehealth would have been conducted by phone without the ability to perform at the very least an observational physical exam of the patient, which is important when prescribing medications to medically frail populations.

If telemedicine goes, how will it affect outpatient palliative care?

If that goes away, I do not know what will happen to outpatient palliative care. I can tell you we will be much less efficient in terms of when we see patients. There will probably be a higher clinic burden to patients, as well as higher financial toxicity to patients (Parking in the structure attached to my office building is $22 per day). And, what about the uncaptured costs associated with transportation for those whose illness prevents them from driving themselves? This can range from Uber costs to the time cost for a patient’s family member to take off work and arrange for childcare in order to drive the patient to a clinic for a visit.

In February, I received emails from the Drug Enforcement Agency suggesting that they, too, may roll back providers’ ability to prescribe controlled substances to patients who are mainly receiving telehealth services. While I understand and fully support the need to curb inappropriate overprescribing of controlled medications, I am concerned about the unintended consequences to cancer patients who live at a remote distance from their oncologists and palliative care providers. I remain hopeful that DEA will consider a carveout exception for those patients who have cancer, are receiving palliative care services, or are deemed to be at the end of life, much like the chronic opioid guidelines developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have done.

Telemedicine in essential care

Back to Jim. Using telehealth and electronic prescribing, our oncology and palliative care programs were able to keep Jim comfortable and at home through the end of his life. He did not have to travel 3 hours each way to get care. He did not have to spend money on parking and gas, and his daughter did not have to take days off work and arrange for a babysitter in order to drive him to our clinic. We partnered with a local pharmacy that was willing to special order medications for Jim when his pain became worse and he required a long-acting opioid. We partnered with a local home health company that kept a close eye on Jim and let us know when he seemed to be declining further, prompting discussions about transitioning to hospice.

I’m proud of the fact that our group helped Jim stay in comfortable surroundings and out of the clinic and hospital over the last 6 months of his life, but that would never have happened without the safe and thoughtful use of telehealth by our team.

Ironically, because of a public health emergency, we were able to provide efficient and high-quality palliative care at the right time, to the right person, in the right place, satisfying CMS goals to provide better care for patients and whole populations at lower costs.

Ms. D’Ambruoso is a hospice and palliative care nurse practitioner for UCLA Health Cancer Care, Santa Monica, Calif.

Heart rate, cardiac phase influence perception of time

People’s perception of time is subjective and based not only on their emotional state but also on heartbeat and heart rate (HR), two new studies suggest.

Researchers studied young adults with an electrocardiogram (ECG), measuring electrical activity at millisecond resolution while participants listened to tones that varied in duration. Participants were asked to report whether certain tones were longer or shorter, in relation to others.

The researchers found that the momentary perception of time was not continuous but rather expanded or contracted with each heartbeat. When the heartbeat preceding a tone was shorter, participants regarded the tone as longer in duration; but when the preceding heartbeat was longer, the participants experienced the tone as shorter.

“Our findings suggest that there is a unique role that cardiac dynamics play in the momentary experience of time,” lead author Saeedah Sadeghi, MSc, a doctoral candidate in the department of psychology at Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., said in an interview.

The study was published online in Psychophysiology.

In a second study, published in the journal Current Biology, a separate team of researchers asked participants to judge whether a brief event – the presentation of a tone or an image – was shorter or longer than a reference duration. ECG was used to track systole and diastole when participants were presented with these events.

The researchers found that the durations were underestimated during systole and overestimated during diastole, suggesting that time seemed to “speed up” or “slow down,” based on cardiac contraction and relaxation. When participants rated the events as more arousing, their perceived durations contracted, even during diastole.

“In our new paper, we show that our heart shapes the perceived duration of events, so time passes quicker when the heart contracts but slower when the heart relaxes,” lead author Irena Arslanova, PhD, postdoctoral researcher in cognitive neuroscience, Royal Holloway University of London, told this news organization.

Temporal ‘wrinkles’

“Subjective time is malleable,” observed Ms. Sadeghi and colleagues in their report. “Rather than being a uniform dimension, perceived duration has ‘wrinkles,’ with certain intervals appearing to dilate or contract relative to objective time” – a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “distortion.”

“We have known that people aren’t always consistent in how they perceive time, and objective duration doesn’t always explain subjective perception of time,” Ms. Sadeghi said.

Although the potential role of the heart in the experience of time has been hypothesized, research into the heart-time connection has been limited, with previous studies focusing primarily on estimating the average cardiac measures on longer time scales over seconds to minutes.

The current study sought to investigate “the beat-by-beat fluctuations of the heart period on the experience of brief moments in time” because, compared with longer time scales, subsecond temporal perception “has different underlying mechanisms” and a subsecond stimulus can be a “small fraction of a heartbeat.”

To home in on this small fraction, the researchers studied 45 participants (aged 18-21), who listened to 210 tones ranging in duration from 80 ms (short) to 188 ms (long). The tones were linearly spaced at 18-ms increments (80, 98, 116, 134, 152, 170, 188).

Participants were asked to categorize each tone as “short” or “long.” All tones were randomly assigned to be synchronized either with the systolic or diastolic phase of the cardiac cycle (50% each). The tones were triggered by participants’ heartbeats.

In addition, participants engaged in a heartbeat-counting activity, in which they were asked not to touch their pulse but to count their heartbeats by tuning in to their bodily sensations at intervals of 25, 35, and 45 seconds.

‘Classical’ response

“Participants exhibited an increased heart period after tone onset, which returned to baseline following an average canonical bell shape,” the authors reported.

The researchers performed regression analyses to determine how, on average, the heart rate before the tone was related to perceived duration or how the amount of change after the tone was related to perceived duration.

They found that when the heart rate was higher before the tone, participants tended to be more accurate in their time perception. When the heartbeat preceding a tone was shorter, participants experienced the tone as longer; conversely, when the heartbeat was longer, they experienced the duration of the identical sound as shorter.

When participants focused their attention on the sounds, their heart rate was affected such that their orienting responses actually changed their heart rate and, in turn, their temporal perception.

“The orienting response is classical,” Ms. Sadeghi said. “When you attend to something unpredictable or novel, the act of orienting attention decreases the HR.”

She explained that the heartbeats are “noise to the brain.” When people need to perceive external events, “a decrease in HR facilitates the intake of things from outside and facilitates sensory intake.”

A lower HR “makes it easier for the person to take in the tone and perceive it, so it feels as though they perceive more of the tone and the duration seems longer – similarly, when the HR decreases.”

It is unknown whether this is a causal relationship, she cautioned, “but it seems as though the decrease in HR somehow makes it easier to ‘get’ more of the tone, which then appears to have longer duration.”

Bidirectional relationship

“We know that experienced time can be distorted,” said Dr. Arslanova. “Time flies by when we’re busy or having fun but drags on when we’re bored or waiting for something, yet we still don’t know how the brain gives rise to such elastic experience of time.”

The brain controls the heart in response to the information the heart provides about the state of the body, she noted, “but we have begun to see more research showing that the heart–brain relationship is bidirectional.”

This means that the heart plays a role in shaping “how we process information and experience emotions.” In this analysis, Dr. Arslanova and colleagues “wanted to study whether the heart also shapes the experience of time.”

To do so, they conducted two experiments.

In the first, participants (n = 28) were presented with brief events during systole or during diastole. The events took the form of an emotionally neutral visual shape or auditory tone, shown for durations of 200 to 400 ms.

Participants were asked whether these events were of longer or shorter duration, compared with a reference duration.

The researchers found significant main effect of cardiac phase systole (F(1,27) = 8.1, P =.01), with stimuli presented at diastole regarded, on average, as 7 ms longer than those presented at systole.

They also found a significant main effect of modality (F(1,27) = 5.7, P = .02), with tones judged, on average, as 13 ms longer than visual stimuli.

“This means that time ‘sped up’ during the heart’s contraction and ‘slowed down’ during the heart’s relaxation,” Dr. Arslanova said.

The effect of cardiac phase on duration perception was independent of changes in HR, the authors noted.

In the second experiment, participants performed a similar task, but this time, it involved the images of faces containing emotional expressions. The researchers again observed a similar pattern of time appearing to speed up during systole and slow down during diastole, with stimuli present at diastole regarded as being an average 9 ms longer than those presented at systole.

These opposing effects of systole and diastole on time perception were present only for low and average arousal ratings (b = 14.4 [SE 3.2], P < .001 and b = 9.2 [2.3], P <.001, respectively). However, this effect disappeared when arousal ratings increased (b = 4.1 [3.2] P =.21).