User login

Specialists think it’s up to the PCP to recommend flu vaccines. But many patients don’t see a PCP every year

A new survey from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases shows that, despite the recommendation that patients who have chronic illnesses receive annual flu vaccines, only 45% of these patients do get them. People with chronic diseases are at increased risk for serious flu-related complications, including hospitalization and death.

The survey looked at physicians’ practices toward flu vaccination and communication between health care providers (HCP) and their adult patients with chronic health conditions.

Overall, less than a third of HCPs (31%) said they recommend annual flu vaccination to all of their patients with chronic health conditions. There were some surprising differences between subspecialists. For example, 72% of patients with a heart problem who saw a cardiologist said that physician recommended the flu vaccine. The recommendation rate dropped to 32% of lung patients seeing a pulmonary physician and only 10% of people with diabetes who saw an endocrinologist.

There is quite a large gap between what physicians and patients say about their interactions. Fully 77% of HCPs who recommend annual flu vaccination say they tell patients when they are at higher risk of complications from influenza. Yet only 48% of patients say they have been given such information.

Although it is critically important information for patients to learn, their risk of influenza is often missing from the discussion. For example, patients with heart disease are six times more likely to have a heart attack within 7 days of flu infection. People with diabetes are six times more likely to be hospitalized from flu and three times more likely to die. Similarly, those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder are at a much higher risk of complications.

One problem is that Yet only 65% of patients with one of these chronic illnesses report seeing their primary care physician at least annually.

Much of the disparity between the patient’s perception of what they were told and the physician’s is “how the ‘recommendation’ is actually made,” William Schaffner, MD, NFID’s medical director and professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Schaffner offered the following example: At the end of the visit, the doctor might say: “It’s that time of the year again – you want to think about getting your flu shot.”

“The doctor thinks they’ve recommended that, but the doctor really has opened the door for you to think about it and leave [yourself] unvaccinated.”

Dr. Schaffner’s alternative? Tell the patient: “‘You’ll get your flu vaccine on the way out. Tom or Sally will give it to you.’ That’s a very different kind of recommendation. And it’s a much greater assurance of providing the vaccine.”

Another major problem, Dr. Schaffner said, is that many specialists “don’t think of vaccination as something that’s included with their routine care” even though they do direct much of the patient’s care. He said that physicians should be more “directive” in their care and that immunizations should be better integrated into routine practice.

Jody Lanard, MD, a retired risk communication consultant who spent many years working with the World Health Organization on disease outbreak communications, said in an interview that this disconnect between physician and patient reports “was really jarring. And it’s actionable!”

She offered several practical suggestions. For one, she said, “the messaging to the specialists has to be very, very empathic. We know you’re already overburdened. And here we’re asking you to do something that you think of as somebody else’s job.” But if your patient gets flu, then your job as the cardiologist or endocrinologist will become more complicated and time-consuming. So getting the patients vaccinated will be a good investment and will make your job easier.

Because of the disparity in patient and physician reports, Dr. Lanard suggested implementing a “feedback mechanism where they [the health care providers] give out the prescription, and then the office calls [the patient] to see if they’ve gotten the shot or not. Because that way it will help correct the mismatch between them thinking that they told the patient and the patient not hearing it.”

Asked about why there might be a big gap between what physicians report they said and what patients heard, Dr. Lanard explained that “physicians often communicate in [a manner] sort of like a checklist. And the patients are focused on one or two things that are high in their minds. And the physician was mentioning some things that are on a separate topic that are not on a patient’s list and it goes right past them.”

Dr. Lanard recommended brief storytelling instead of checklists. For example: “I’ve been treating your diabetes for 10 years. During this last flu season, several of my diabetic patients had a really hard time when they caught the flu. So now I’m trying harder to remember to remind you to get your flu shots.”

She urged HCPs to “make it more personal ... but it can still be scripted in advance as part of something that [you’re] remembering to do during the check.” She added that their professional associations may be able to send them suggested language they can adapt.

Finally, Dr. Lanard cautioned about vaccine myths. “The word myth is so insulting. It’s basically a word that sends the signal that you’re an idiot.”

She advised specialists to avoid the word “myth,” which will make the person defensive. Instead, say something like, “A lot of people, even some of my own family members, think the flu vaccine gives you the flu. ... But it doesn’t. And then you go into the reality.”

Dr. Lanard suggested that specialists implement the follow-up calls and close the feedback loop, saying: “If they did the survey a few years later, I bet that gap would narrow.”

Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Lanard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases shows that, despite the recommendation that patients who have chronic illnesses receive annual flu vaccines, only 45% of these patients do get them. People with chronic diseases are at increased risk for serious flu-related complications, including hospitalization and death.

The survey looked at physicians’ practices toward flu vaccination and communication between health care providers (HCP) and their adult patients with chronic health conditions.

Overall, less than a third of HCPs (31%) said they recommend annual flu vaccination to all of their patients with chronic health conditions. There were some surprising differences between subspecialists. For example, 72% of patients with a heart problem who saw a cardiologist said that physician recommended the flu vaccine. The recommendation rate dropped to 32% of lung patients seeing a pulmonary physician and only 10% of people with diabetes who saw an endocrinologist.

There is quite a large gap between what physicians and patients say about their interactions. Fully 77% of HCPs who recommend annual flu vaccination say they tell patients when they are at higher risk of complications from influenza. Yet only 48% of patients say they have been given such information.

Although it is critically important information for patients to learn, their risk of influenza is often missing from the discussion. For example, patients with heart disease are six times more likely to have a heart attack within 7 days of flu infection. People with diabetes are six times more likely to be hospitalized from flu and three times more likely to die. Similarly, those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder are at a much higher risk of complications.

One problem is that Yet only 65% of patients with one of these chronic illnesses report seeing their primary care physician at least annually.

Much of the disparity between the patient’s perception of what they were told and the physician’s is “how the ‘recommendation’ is actually made,” William Schaffner, MD, NFID’s medical director and professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Schaffner offered the following example: At the end of the visit, the doctor might say: “It’s that time of the year again – you want to think about getting your flu shot.”

“The doctor thinks they’ve recommended that, but the doctor really has opened the door for you to think about it and leave [yourself] unvaccinated.”

Dr. Schaffner’s alternative? Tell the patient: “‘You’ll get your flu vaccine on the way out. Tom or Sally will give it to you.’ That’s a very different kind of recommendation. And it’s a much greater assurance of providing the vaccine.”

Another major problem, Dr. Schaffner said, is that many specialists “don’t think of vaccination as something that’s included with their routine care” even though they do direct much of the patient’s care. He said that physicians should be more “directive” in their care and that immunizations should be better integrated into routine practice.

Jody Lanard, MD, a retired risk communication consultant who spent many years working with the World Health Organization on disease outbreak communications, said in an interview that this disconnect between physician and patient reports “was really jarring. And it’s actionable!”

She offered several practical suggestions. For one, she said, “the messaging to the specialists has to be very, very empathic. We know you’re already overburdened. And here we’re asking you to do something that you think of as somebody else’s job.” But if your patient gets flu, then your job as the cardiologist or endocrinologist will become more complicated and time-consuming. So getting the patients vaccinated will be a good investment and will make your job easier.

Because of the disparity in patient and physician reports, Dr. Lanard suggested implementing a “feedback mechanism where they [the health care providers] give out the prescription, and then the office calls [the patient] to see if they’ve gotten the shot or not. Because that way it will help correct the mismatch between them thinking that they told the patient and the patient not hearing it.”

Asked about why there might be a big gap between what physicians report they said and what patients heard, Dr. Lanard explained that “physicians often communicate in [a manner] sort of like a checklist. And the patients are focused on one or two things that are high in their minds. And the physician was mentioning some things that are on a separate topic that are not on a patient’s list and it goes right past them.”

Dr. Lanard recommended brief storytelling instead of checklists. For example: “I’ve been treating your diabetes for 10 years. During this last flu season, several of my diabetic patients had a really hard time when they caught the flu. So now I’m trying harder to remember to remind you to get your flu shots.”

She urged HCPs to “make it more personal ... but it can still be scripted in advance as part of something that [you’re] remembering to do during the check.” She added that their professional associations may be able to send them suggested language they can adapt.

Finally, Dr. Lanard cautioned about vaccine myths. “The word myth is so insulting. It’s basically a word that sends the signal that you’re an idiot.”

She advised specialists to avoid the word “myth,” which will make the person defensive. Instead, say something like, “A lot of people, even some of my own family members, think the flu vaccine gives you the flu. ... But it doesn’t. And then you go into the reality.”

Dr. Lanard suggested that specialists implement the follow-up calls and close the feedback loop, saying: “If they did the survey a few years later, I bet that gap would narrow.”

Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Lanard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new survey from the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases shows that, despite the recommendation that patients who have chronic illnesses receive annual flu vaccines, only 45% of these patients do get them. People with chronic diseases are at increased risk for serious flu-related complications, including hospitalization and death.

The survey looked at physicians’ practices toward flu vaccination and communication between health care providers (HCP) and their adult patients with chronic health conditions.

Overall, less than a third of HCPs (31%) said they recommend annual flu vaccination to all of their patients with chronic health conditions. There were some surprising differences between subspecialists. For example, 72% of patients with a heart problem who saw a cardiologist said that physician recommended the flu vaccine. The recommendation rate dropped to 32% of lung patients seeing a pulmonary physician and only 10% of people with diabetes who saw an endocrinologist.

There is quite a large gap between what physicians and patients say about their interactions. Fully 77% of HCPs who recommend annual flu vaccination say they tell patients when they are at higher risk of complications from influenza. Yet only 48% of patients say they have been given such information.

Although it is critically important information for patients to learn, their risk of influenza is often missing from the discussion. For example, patients with heart disease are six times more likely to have a heart attack within 7 days of flu infection. People with diabetes are six times more likely to be hospitalized from flu and three times more likely to die. Similarly, those with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder are at a much higher risk of complications.

One problem is that Yet only 65% of patients with one of these chronic illnesses report seeing their primary care physician at least annually.

Much of the disparity between the patient’s perception of what they were told and the physician’s is “how the ‘recommendation’ is actually made,” William Schaffner, MD, NFID’s medical director and professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., told this news organization. Dr. Schaffner offered the following example: At the end of the visit, the doctor might say: “It’s that time of the year again – you want to think about getting your flu shot.”

“The doctor thinks they’ve recommended that, but the doctor really has opened the door for you to think about it and leave [yourself] unvaccinated.”

Dr. Schaffner’s alternative? Tell the patient: “‘You’ll get your flu vaccine on the way out. Tom or Sally will give it to you.’ That’s a very different kind of recommendation. And it’s a much greater assurance of providing the vaccine.”

Another major problem, Dr. Schaffner said, is that many specialists “don’t think of vaccination as something that’s included with their routine care” even though they do direct much of the patient’s care. He said that physicians should be more “directive” in their care and that immunizations should be better integrated into routine practice.

Jody Lanard, MD, a retired risk communication consultant who spent many years working with the World Health Organization on disease outbreak communications, said in an interview that this disconnect between physician and patient reports “was really jarring. And it’s actionable!”

She offered several practical suggestions. For one, she said, “the messaging to the specialists has to be very, very empathic. We know you’re already overburdened. And here we’re asking you to do something that you think of as somebody else’s job.” But if your patient gets flu, then your job as the cardiologist or endocrinologist will become more complicated and time-consuming. So getting the patients vaccinated will be a good investment and will make your job easier.

Because of the disparity in patient and physician reports, Dr. Lanard suggested implementing a “feedback mechanism where they [the health care providers] give out the prescription, and then the office calls [the patient] to see if they’ve gotten the shot or not. Because that way it will help correct the mismatch between them thinking that they told the patient and the patient not hearing it.”

Asked about why there might be a big gap between what physicians report they said and what patients heard, Dr. Lanard explained that “physicians often communicate in [a manner] sort of like a checklist. And the patients are focused on one or two things that are high in their minds. And the physician was mentioning some things that are on a separate topic that are not on a patient’s list and it goes right past them.”

Dr. Lanard recommended brief storytelling instead of checklists. For example: “I’ve been treating your diabetes for 10 years. During this last flu season, several of my diabetic patients had a really hard time when they caught the flu. So now I’m trying harder to remember to remind you to get your flu shots.”

She urged HCPs to “make it more personal ... but it can still be scripted in advance as part of something that [you’re] remembering to do during the check.” She added that their professional associations may be able to send them suggested language they can adapt.

Finally, Dr. Lanard cautioned about vaccine myths. “The word myth is so insulting. It’s basically a word that sends the signal that you’re an idiot.”

She advised specialists to avoid the word “myth,” which will make the person defensive. Instead, say something like, “A lot of people, even some of my own family members, think the flu vaccine gives you the flu. ... But it doesn’t. And then you go into the reality.”

Dr. Lanard suggested that specialists implement the follow-up calls and close the feedback loop, saying: “If they did the survey a few years later, I bet that gap would narrow.”

Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Lanard disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Metabolites implicated in CHD development in African Americans

Selected metabolic biomarkers may influence disease risk and progression in African American and White persons in different ways, a cohort study of the landmark Jackson Heart Study has found.

The investigators identified 22 specific metabolites that seem to influence incident CHD risk in African American patients – 13 metabolites that were also replicated in a multiethnic population and 9 novel metabolites that include N-acylamides and leucine, a branched-chain amino acid.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that an N-acylamide as a class of molecule has been shown to be associated with incident coronary heart disease,” lead study author Daniel E. Cruz, MD, an instructor at Harvard Medical School in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview.

The researchers analyzed targeted plasma metabolomic profiles of 2,346 participants in the Jackson Heart Study, a prospective population-based cohort study in the Mississippi city that included 5,306 African American patients evaluated over 15 years. They then performed a replication analysis of CHD-associated metabolites among 1,588 multiethnic participants in the Women’s Health Initiative, another population-based cohort study that included 161,808 postmenopausal women, also over 15 years. In all, the study, published in JAMA Cardiology, identified 46 metabolites that were associated with incident CHD up to 16 years before the incident event

Dr. Cruz said the “most interesting” findings were the roles of the N-acylamide linoleoyl ethanolamide and leucine. The former is of interest “because it is a lipid-signaling molecule that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages; the influence and effects on macrophages are of particular interest because of macrophages’ central role in atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease,” he said.

Leucine draws interest because, in this study population, it was linked to a reduced risk of incident CHD. The researchers cited four previous studies in predominantly non-Hispanic White populations that found no association between branched-chain amino acids and incident CHD in Circulation, Stroke Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine, and Atherosclerosis. Other branched-amino acids included in the analysis trended toward a decreased risk of CHD, but those didn’t achieve the same statistical significance as that of leucine, Dr. Cruz said.

“In some of the analyses we did, there was a subset of metabolites that the associations with CHD appeared to be different between self-identified African Americans in the Jackson cohort vs. self-identified non-Hispanic Whites, and leucine was one of them,” Dr. Cruz said.

He emphasized that this study “is not a genetic analysis” because the participants self-identified their race. “So our next step is to figure out why this difference appears between these self-identified groups,” Dr. Cruz said. “We suspect environmental factors play a role – psychological stress, diet, income level, to name a few – but we are also interested to see if there are genetic causes.”

The results “are not clinically applicable,” Dr. Cruz said, but they do point to a need for more ethnically and racially diverse study populations. “The big picture is that, before we go implementing novel biomarkers into clinical practice, we need to make sure that they are accurate across different populations of people,” he said. “The only way to do this is to study different groups with the same rigor and vigor and thoughtfulness as any other group.”

These findings fall in line with other studies that found other nonmetabolomic biomarkers have countervailing effects on CHD risk in African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites, said Christie M. Ballantyne, MD, chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. For example, African Americans have been found to have lower triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels than those of Whites.

The study “points out that there may be important biological differences in the metabolic pathways and abnormalities in the development of CHD between races,” Dr. Ballantyne said. “This further emphasizes both the importance and challenge of testing therapies in multiple racial/ethnic groups and with more even representation between men and women.”

Combining metabolomic profiling along with other biomarkers and possibly genetics may be helpful to “personalize” therapies in the future, he added.

Dr. Cruz and Dr. Ballantyne have no relevant relationships to disclose.

Selected metabolic biomarkers may influence disease risk and progression in African American and White persons in different ways, a cohort study of the landmark Jackson Heart Study has found.

The investigators identified 22 specific metabolites that seem to influence incident CHD risk in African American patients – 13 metabolites that were also replicated in a multiethnic population and 9 novel metabolites that include N-acylamides and leucine, a branched-chain amino acid.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that an N-acylamide as a class of molecule has been shown to be associated with incident coronary heart disease,” lead study author Daniel E. Cruz, MD, an instructor at Harvard Medical School in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview.

The researchers analyzed targeted plasma metabolomic profiles of 2,346 participants in the Jackson Heart Study, a prospective population-based cohort study in the Mississippi city that included 5,306 African American patients evaluated over 15 years. They then performed a replication analysis of CHD-associated metabolites among 1,588 multiethnic participants in the Women’s Health Initiative, another population-based cohort study that included 161,808 postmenopausal women, also over 15 years. In all, the study, published in JAMA Cardiology, identified 46 metabolites that were associated with incident CHD up to 16 years before the incident event

Dr. Cruz said the “most interesting” findings were the roles of the N-acylamide linoleoyl ethanolamide and leucine. The former is of interest “because it is a lipid-signaling molecule that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages; the influence and effects on macrophages are of particular interest because of macrophages’ central role in atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease,” he said.

Leucine draws interest because, in this study population, it was linked to a reduced risk of incident CHD. The researchers cited four previous studies in predominantly non-Hispanic White populations that found no association between branched-chain amino acids and incident CHD in Circulation, Stroke Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine, and Atherosclerosis. Other branched-amino acids included in the analysis trended toward a decreased risk of CHD, but those didn’t achieve the same statistical significance as that of leucine, Dr. Cruz said.

“In some of the analyses we did, there was a subset of metabolites that the associations with CHD appeared to be different between self-identified African Americans in the Jackson cohort vs. self-identified non-Hispanic Whites, and leucine was one of them,” Dr. Cruz said.

He emphasized that this study “is not a genetic analysis” because the participants self-identified their race. “So our next step is to figure out why this difference appears between these self-identified groups,” Dr. Cruz said. “We suspect environmental factors play a role – psychological stress, diet, income level, to name a few – but we are also interested to see if there are genetic causes.”

The results “are not clinically applicable,” Dr. Cruz said, but they do point to a need for more ethnically and racially diverse study populations. “The big picture is that, before we go implementing novel biomarkers into clinical practice, we need to make sure that they are accurate across different populations of people,” he said. “The only way to do this is to study different groups with the same rigor and vigor and thoughtfulness as any other group.”

These findings fall in line with other studies that found other nonmetabolomic biomarkers have countervailing effects on CHD risk in African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites, said Christie M. Ballantyne, MD, chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. For example, African Americans have been found to have lower triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels than those of Whites.

The study “points out that there may be important biological differences in the metabolic pathways and abnormalities in the development of CHD between races,” Dr. Ballantyne said. “This further emphasizes both the importance and challenge of testing therapies in multiple racial/ethnic groups and with more even representation between men and women.”

Combining metabolomic profiling along with other biomarkers and possibly genetics may be helpful to “personalize” therapies in the future, he added.

Dr. Cruz and Dr. Ballantyne have no relevant relationships to disclose.

Selected metabolic biomarkers may influence disease risk and progression in African American and White persons in different ways, a cohort study of the landmark Jackson Heart Study has found.

The investigators identified 22 specific metabolites that seem to influence incident CHD risk in African American patients – 13 metabolites that were also replicated in a multiethnic population and 9 novel metabolites that include N-acylamides and leucine, a branched-chain amino acid.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time that an N-acylamide as a class of molecule has been shown to be associated with incident coronary heart disease,” lead study author Daniel E. Cruz, MD, an instructor at Harvard Medical School in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview.

The researchers analyzed targeted plasma metabolomic profiles of 2,346 participants in the Jackson Heart Study, a prospective population-based cohort study in the Mississippi city that included 5,306 African American patients evaluated over 15 years. They then performed a replication analysis of CHD-associated metabolites among 1,588 multiethnic participants in the Women’s Health Initiative, another population-based cohort study that included 161,808 postmenopausal women, also over 15 years. In all, the study, published in JAMA Cardiology, identified 46 metabolites that were associated with incident CHD up to 16 years before the incident event

Dr. Cruz said the “most interesting” findings were the roles of the N-acylamide linoleoyl ethanolamide and leucine. The former is of interest “because it is a lipid-signaling molecule that has been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages; the influence and effects on macrophages are of particular interest because of macrophages’ central role in atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease,” he said.

Leucine draws interest because, in this study population, it was linked to a reduced risk of incident CHD. The researchers cited four previous studies in predominantly non-Hispanic White populations that found no association between branched-chain amino acids and incident CHD in Circulation, Stroke Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine, and Atherosclerosis. Other branched-amino acids included in the analysis trended toward a decreased risk of CHD, but those didn’t achieve the same statistical significance as that of leucine, Dr. Cruz said.

“In some of the analyses we did, there was a subset of metabolites that the associations with CHD appeared to be different between self-identified African Americans in the Jackson cohort vs. self-identified non-Hispanic Whites, and leucine was one of them,” Dr. Cruz said.

He emphasized that this study “is not a genetic analysis” because the participants self-identified their race. “So our next step is to figure out why this difference appears between these self-identified groups,” Dr. Cruz said. “We suspect environmental factors play a role – psychological stress, diet, income level, to name a few – but we are also interested to see if there are genetic causes.”

The results “are not clinically applicable,” Dr. Cruz said, but they do point to a need for more ethnically and racially diverse study populations. “The big picture is that, before we go implementing novel biomarkers into clinical practice, we need to make sure that they are accurate across different populations of people,” he said. “The only way to do this is to study different groups with the same rigor and vigor and thoughtfulness as any other group.”

These findings fall in line with other studies that found other nonmetabolomic biomarkers have countervailing effects on CHD risk in African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites, said Christie M. Ballantyne, MD, chief of cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. For example, African Americans have been found to have lower triglyceride and HDL cholesterol levels than those of Whites.

The study “points out that there may be important biological differences in the metabolic pathways and abnormalities in the development of CHD between races,” Dr. Ballantyne said. “This further emphasizes both the importance and challenge of testing therapies in multiple racial/ethnic groups and with more even representation between men and women.”

Combining metabolomic profiling along with other biomarkers and possibly genetics may be helpful to “personalize” therapies in the future, he added.

Dr. Cruz and Dr. Ballantyne have no relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

U.S. obesity rates soar in early adulthood

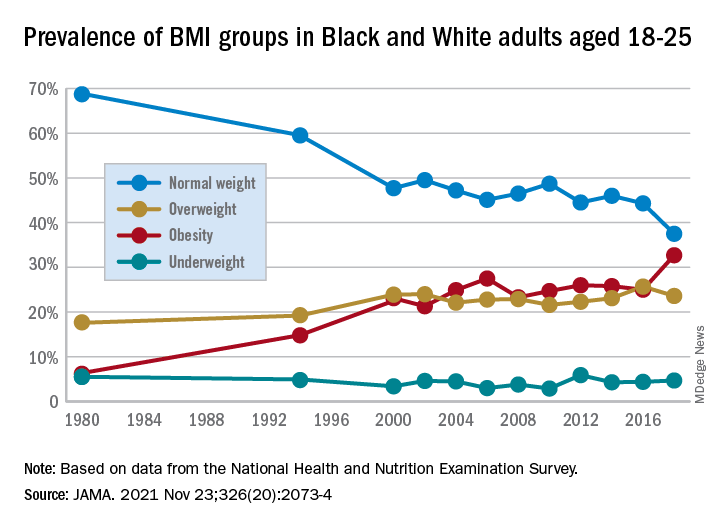

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

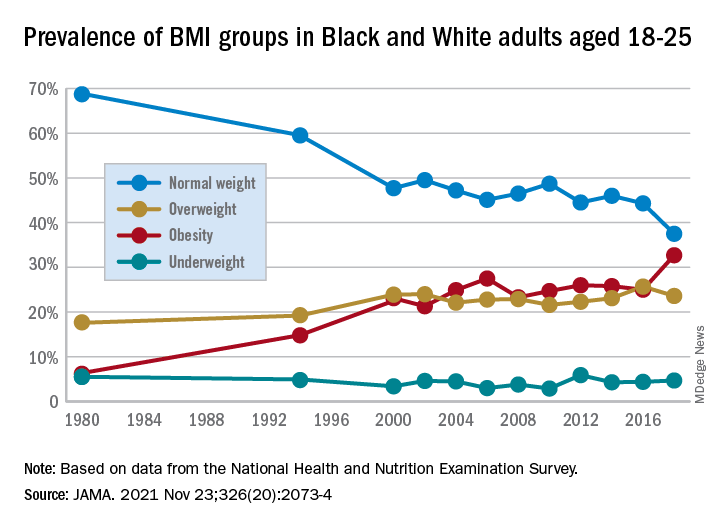

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

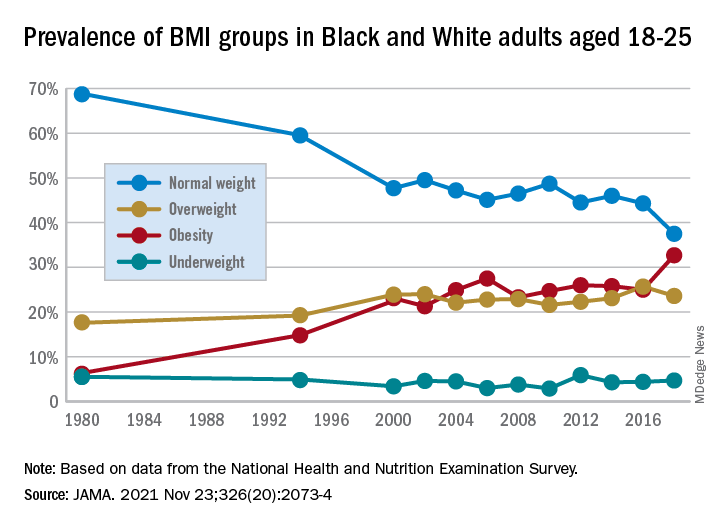

Obesity rates among “emerging adults” aged 18-25 have soared in the United States in recent decades with the mean body mass index (BMI) for these young adults now in the overweight category, according to research highlighting troubling trends in an often-overlooked age group.

While similar patterns have been observed in other age groups, including adolescents (ages 12-19) and young adults (ages 20-39) across recent decades, emerging adulthood tends to get less attention in the evaluation of obesity trends.

“Emerging adulthood may be a key period for preventing and treating obesity given that habits formed during this period often persist through the remainder of the life course,” write the authors of the study, which was published online Nov. 23 in JAMA.

“There is an urgent need for research on risk factors contributing to obesity during this developmental stage to inform the design of interventions as well as policies aimed at prevention,” they add.

They found that by 2018 a third of all young adults had obesity, compared with just 6% at the beginning of the study periods in 1976.

Studying the ages of transition

The findings are from an analysis of 8,015 emerging adults aged 18-25 in the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), including NHANES II (1976-1980), NHANES III (1988-1994), and the continuous NHANES cycles from 1999 through 2018.

About half (3,965) of participants were female, 3,037 were non-Hispanic Black, and 2,386 met the criteria for household poverty.

The results showed substantial increases in mean BMI among emerging adults from a level in the normal range, at 23.1 kg/m2, in 1976-1980, increasing to 27.7 kg/m2 (overweight) in 2017-2018 (P = .006).

The prevalence of obesity (BMI 30.0 kg/m2 or higher) in the emerging adult age group soared from 6.2% between 1976-1980 to 32.7% in 2017-2018 (P = .007).

Meanwhile, the rate of those with normal/healthy weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2) dropped from 68.7% to 37.5% (P = .005) over the same period.

Sensitivity analyses that were limited to continuous NHANES cycles showed similar results.

First author Alejandra Ellison-Barnes, MD, MPH, said the trends are consistent with rising obesity rates in the population as a whole – other studies have shown increases in obesity among children, adolescents, and adults over the same period – but are nevertheless striking, she stressed.

Young adults now fall into overweight category

“While we were not surprised by the general trend, given what is known about the increasing prevalence of obesity in both children and adults, we were surprised by the magnitude of the increase in prevalence and that the mean BMI in this age group now falls in the overweight range,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes, of the Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

She said she is not aware of other studies that have looked at obesity trends specifically among emerging adults.

However, considering the substantial life changes and growing independence, the life stage is important to understand in terms of dietary/lifestyle patterns.

“We theorize that emerging adulthood is a critical period for obesity development given that it is a time when individuals are often undergoing major life transitions such as leaving home, attending higher education, entering the workforce, and developing new relationships,” she emphasized.

As far as causes are concerned, “societal and cultural trends in these areas over the past several decades may have played a role in the observed changes,” she speculated.

The study population was limited to non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White individuals due to changes in how NHANES assessed race and ethnicity over time. Therefore, a study limitation is that the patterns observed may not be generalizable to other races and ethnicities, the authors note.

However, considering the influence lifestyle changes can have, early adulthood “may be an ideal time to intervene in the clinical setting to prevent, manage, or reverse obesity to prevent adverse health outcomes in the future,” Dr. Ellison-Barnes said.

Dr. Ellison-Barnes has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Evaluation of Intermittent Energy Restriction and Continuous Energy Restriction on Weight Loss and Blood Pressure Control in Overweight and Obese Patients With Hypertension

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the effects of intermittent energy restriction (IER) with those of continuous energy restriction (CER) on blood pressure control and weight loss in overweight and obese patients with hypertension during a 6-month period.

Design. Randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. The trial was conducted at the Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University from June 1, 2020, to April 30, 2021. Chinese adults were recruited using advertisements and flyers posted in the hospital and local communities. Prior to participation in study activities, all participants gave informed consent prior to recruitment and were provided compensation in the form of a $38 voucher at 3 and 6 months for their time for participating in the study.

The main inclusion criteria were patients between the ages of 18 and 70 years, hypertension, and body mass index (BMI) ranging from 24 to 40 kg/m2. The exclusion criteria were systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 120 mmHg, type 1 or 2 diabetes with a history of severe hypoglycemic episodes, pregnancy or breastfeeding, usage of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, weight loss > 5 kg within the past 3 months or previous weight loss surgery, and inability to adhere to the dietary protocol.

Of the 294 participants screened for eligibility, 205 were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the IER group (n = 102) or the CER group (n = 103), stratified by sex and BMI (as overweight or obese). All participants were required to have a stable medication regimen and weight in the 3 months prior to enrollment and not to use weight-loss drugs or vitamin supplements for the duration of the study. Researchers and participants were not blinded to the study group assignment.

Interventions. Participants randomly assigned to the IER group followed a 5:2 eating pattern: a very-low-energy diet of 500-600 kcal for 2 days of the week along with their usual diet for the other 5 days. The 2 days of calorie restriction could be consecutive or nonconsecutive, with a minimum of 0.8 g supplemental protein per kg of body weight per day, in accordance with the 2016 Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents. The CER group was advised to consume 1000 kcal/day for women and 1200 kcal/day for men on a 7-day energy restriction. That is, they were prescribed a daily 25% restriction based on the general principles of a Mediterranean-type diet (30% fat, 45-50% carbohydrate, and 20-25% protein).

Both groups received dietary education from a qualified dietitian and were recommended to maintain their current daily activity levels throughout the trial. Written dietary information brochures with portion advice and sample meal plans were provided to improve compliance in each group. All participants received a digital cooking scale to weigh foods to ensure accuracy of intake and were required to keep a food diary while following the recommended recipe on 2 days/week during calorie restriction to help with adherence. No food was provided. All participants were followed up by regular outpatient visits to both cardiologists and dietitians once a month. Diet checklists, activity schedules, and weight were reviewed to assess compliance with dietary advice at each visit.

Of note, participants were encouraged to measure and record their BP twice daily, and if 2 consecutive BP readings were < 110/70 mmHg and/or accompanied by hypotensive episodes with symptoms (dizziness, nausea, headache, and fatigue), they were asked to contact the investigators directly. Antihypertensive medication changes were then made in consultation with cardiologists. In addition, a medication management protocol (ie, doses of antidiabetic medications, including insulin and sulfonylurea) was designed to avoid hypoglycemia. Medication could be reduced in the CER group based on the basal dose at the endocrinologist’s discretion. In the IER group, insulin and sulfonylureas were discontinued on calorie restriction days only, and long-acting insulin was discontinued the night before the IER day. Insulin was not to be resumed until a full day’s caloric intake was achieved.

Measures and analysis. The primary outcomes of this study were changes in BP and weight (measured using an automatic digital sphygmomanometer and an electronic scale), and the secondary outcomes were changes in body composition (assessed by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scanning), as well as glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and blood lipids after 6 months. All outcome measures were recorded at baseline and at each monthly visit. Incidence rates of hypoglycemia were based on blood glucose (defined as blood glucose < 70 mg/dL) and/or symptomatic hypoglycemia (symptoms of sweating, paleness, dizziness, and confusion). Two cardiologists who were blind to the patients’ diet condition measured and recorded all pertinent clinical parameters and adjudicated serious adverse events.

Data were compared using independent-samples t-tests or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorial variables as appropriate. Repeated-measures ANOVA via a linear mixed model was employed to test the effects of diet, time, and their interaction. In subgroup analyses, differential effects of the intervention on the primary outcomes were evaluated with respect to patients’ level of education, domicile, and sex based on the statistical significance of the interaction term for the subgroup of interest in the multivariate model. Analyses were performed based on completers and on an intention-to-treat principle.

Main results. Among the 205 randomized participants, 118 were women and 87 were men; mean (SD) age was 50.5 (8.8) years; mean (SD) BMI was 28.7 (2.6); mean (SD) SBP was 143 (10) mmHg; and mean (SD) DBP was 91 (9) mmHg. At the end of the 6-month intervention, 173 (84.4%) completed the study (IER group: n = 88; CER group: n = 85). Both groups had similar dropout rates at 6 months (IER group: 14 participants [13.7%]; CER group: 18 participants [17.5%]; P = .83) and were well matched for baseline characteristics except for triglyceride levels.

In the completers analysis, both groups experienced significant reductions in weight (mean [SEM]), but there was no difference between treatment groups (−7.2 [0.6] kg in the IER group vs −7.1 [0.6] kg in the CER group; diet by time P = .72). Similarly, the change in SBP and DBP achieved was statistically significant over time, but there was also no difference between the dietary interventions (−8 [0.7] mmHg in the IER group vs −8 [0.6] mmHg in the CER group, diet by time P = .68; −6 [0.6] mmHg in the IER group vs −6 [0.5] mmHg in the CER group, diet by time P = .53]. Subgroup analyses of the association of the intervention with weight, SBP and DBP by sex, education, and domicile showed no significant between-group differences.

All measures of body composition decreased significantly at 6 months with both groups experiencing comparable reductions in total fat mass (−5.5 [0.6] kg in the IER group vs −4.8 [0.5] kg in the CER group, diet by time P = .08) and android fat mass (−1.1 [0.2] kg in the IER group vs −0.8 [0.2] kg in the CER group, diet by time P = .16). Of note, participants in the CER group lost significantly more total fat-free mass than did participants in the IER group (mean [SEM], −2.3 [0.2] kg vs −1.7 [0.2] kg; P = .03], and there was a trend toward a greater change in total fat mass in the IER group (P = .08). The secondary outcome of mean (SEM) HbA1c (−0.2% [0.1%]) and blood lipid levels (triglyceride level, −1.0 [0.3] mmol/L; total cholesterol level, −0.9 [0.2] mmol/L; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, −0.9 [0.2 mmol/L; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, 0.7 [0.3] mmol/L] improved with weight loss (P < .05), with no differences between groups (diet by time P > .05).

The intention-to-treat analysis demonstrated that IER and CER are equally effective for weight loss and blood pressure control: both groups experienced significant reductions in weight, SBP, and DBP, but with no difference between treatment groups – mean (SEM) weight change with IER was −7.0 (0.6) kg vs −6.8 (0.6) kg with CER; the mean (SEM) SBP with IER was −7 (0.7) mmHg vs −7 (0.6) mmHg with CER; and the mean (SEM) DBP with IER was −6 (0.5) mmHg vs −5 (0.5) mmHg with CER, (diet by time P = .62, .39, and .41, respectively). There were favorable improvements in

Conclusion. A 2-day severe energy restriction with 5 days of habitual eating compared to 7 days of CER provides an acceptable alternative for BP control and weight loss in overweight and obese individuals with hypertension after 6 months. IER may offer a useful alternative strategy for this population, who find continuous weight-loss diets too difficult to maintain.

Commentary

Globally, obesity represents a major health challenge as it substantially increases the risk of diseases such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease.1 Lifestyle modifications, including weight loss and increased physical activity, are recommended in major guidelines as a first-step intervention in the treatment of hypertensive patients.2 However, lifestyle and behavioral interventions aimed at reducing calorie intake through low-calorie dieting is challenging as it is dependent on individual motivation and adherence to a strict, continuous protocol. Further, CER strategies have limited effectiveness because complex and persistent hormonal, metabolic, and neurochemical adaptations defend against weight loss and promote weight regain.3-4 IER has drawn attention in the popular media as an alternative to CER due to its feasibility and even potential for higher rates of compliance.5

This study adds to the literature as it is the first randomized controlled trial (to the knowledge of the authors at the time of publication) to explore 2 forms of energy restriction – CER and IER – and their impact on weight loss, BP, body composition, HbA1c, and blood lipid levels in overweight and obese patients with high blood pressure. Results from this study showed that IER is as effective as, but not superior to, CER (in terms of the outcomes measures assessed). Specifically, findings highlighted that the 5:2 diet is an effective strategy and noninferior to that of daily calorie restriction for BP and weight control. In addition, both weight loss and BP reduction were greater in a subgroup of obese compared with overweight participants, which indicates that obese populations may benefit more from energy restriction. As the authors highlight, this study both aligns with and expands on current related literature.

This study has both strengths and limitations, especially with regard to the design and data analysis strategy. A key strength is the randomized controlled trial design which enables increased internal validity and decreases several sources of bias, including selection bias and confounding. In addition, it was also designed as a pragmatic trial, with the protocol reflecting efforts to replicate the real-world environment by not supplying meal replacements or food. Notably, only 9 patients could not comply with the protocol, indicating that acceptability of the diet protocol was high. However, as this was only a 6-month long study, further studies are needed to determine whether a 5:2 diet is sustainable (and effective) in the long-term compared with CER, which the authors highlight. The study was also adequately powered to detect clinically meaningful differences in weight loss and SBP, and appropriate analyses were performed on both the basis of completers and on an intention-to-treat principle. However, further studies are needed that are adequately powered to also detect clinically meaningful differences in the other measures, ie, body composition, HbA1c, and blood lipid levels. Importantly, generalizability of findings from this study is limited as the study population comprises only Chinese adults, predominately middle-aged, overweight, and had mildly to moderately elevated SBP and DBP, and excluded diabetic patients. Thus, findings are not necessarily applicable to individuals with highly elevated blood pressure or poorly controlled diabetes.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Results of this study demonstrated that IER is an effective alternative diet strategy for weight loss and blood pressure control in overweight and obese patients with hypertension and is comparable to CER. This is relevant for clinical practice as IER may be easier to maintain in this population compared to continuous weight-loss diets. Importantly, both types of calorie restriction require clinical oversight as medication changes and periodic monitoring of hypotensive and hypoglycemic episodes are needed. Clinicians should consider what is feasible and sustainable for their patients when recommending intermittent energy restriction.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):288-298. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8

2. Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global hypertension practice guidelines. J Hypertens. 2020;38(6):982-1004. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000002453

3. Müller MJ, Enderle J, Bosy-Westphal A. Changes in Energy Expenditure with Weight Gain and Weight Loss in Humans. Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5(4):413-423. doi:10.1007/s13679-016-0237-4

4. Sainsbury A, Wood RE, Seimon RV, et al. Rationale for novel intermittent dieting strategies to attenuate adaptive responses to energy restriction. Obes Rev. 2018;19 Suppl 1:47–60. doi:10.1111/obr.12787

5. Davis CS, Clarke RE, Coulter SN, et al. Intermittent energy restriction and weight loss: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(3):292-299. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2015.195

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the effects of intermittent energy restriction (IER) with those of continuous energy restriction (CER) on blood pressure control and weight loss in overweight and obese patients with hypertension during a 6-month period.

Design. Randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. The trial was conducted at the Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University from June 1, 2020, to April 30, 2021. Chinese adults were recruited using advertisements and flyers posted in the hospital and local communities. Prior to participation in study activities, all participants gave informed consent prior to recruitment and were provided compensation in the form of a $38 voucher at 3 and 6 months for their time for participating in the study.

The main inclusion criteria were patients between the ages of 18 and 70 years, hypertension, and body mass index (BMI) ranging from 24 to 40 kg/m2. The exclusion criteria were systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 120 mmHg, type 1 or 2 diabetes with a history of severe hypoglycemic episodes, pregnancy or breastfeeding, usage of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, weight loss > 5 kg within the past 3 months or previous weight loss surgery, and inability to adhere to the dietary protocol.

Of the 294 participants screened for eligibility, 205 were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the IER group (n = 102) or the CER group (n = 103), stratified by sex and BMI (as overweight or obese). All participants were required to have a stable medication regimen and weight in the 3 months prior to enrollment and not to use weight-loss drugs or vitamin supplements for the duration of the study. Researchers and participants were not blinded to the study group assignment.

Interventions. Participants randomly assigned to the IER group followed a 5:2 eating pattern: a very-low-energy diet of 500-600 kcal for 2 days of the week along with their usual diet for the other 5 days. The 2 days of calorie restriction could be consecutive or nonconsecutive, with a minimum of 0.8 g supplemental protein per kg of body weight per day, in accordance with the 2016 Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents. The CER group was advised to consume 1000 kcal/day for women and 1200 kcal/day for men on a 7-day energy restriction. That is, they were prescribed a daily 25% restriction based on the general principles of a Mediterranean-type diet (30% fat, 45-50% carbohydrate, and 20-25% protein).

Both groups received dietary education from a qualified dietitian and were recommended to maintain their current daily activity levels throughout the trial. Written dietary information brochures with portion advice and sample meal plans were provided to improve compliance in each group. All participants received a digital cooking scale to weigh foods to ensure accuracy of intake and were required to keep a food diary while following the recommended recipe on 2 days/week during calorie restriction to help with adherence. No food was provided. All participants were followed up by regular outpatient visits to both cardiologists and dietitians once a month. Diet checklists, activity schedules, and weight were reviewed to assess compliance with dietary advice at each visit.

Of note, participants were encouraged to measure and record their BP twice daily, and if 2 consecutive BP readings were < 110/70 mmHg and/or accompanied by hypotensive episodes with symptoms (dizziness, nausea, headache, and fatigue), they were asked to contact the investigators directly. Antihypertensive medication changes were then made in consultation with cardiologists. In addition, a medication management protocol (ie, doses of antidiabetic medications, including insulin and sulfonylurea) was designed to avoid hypoglycemia. Medication could be reduced in the CER group based on the basal dose at the endocrinologist’s discretion. In the IER group, insulin and sulfonylureas were discontinued on calorie restriction days only, and long-acting insulin was discontinued the night before the IER day. Insulin was not to be resumed until a full day’s caloric intake was achieved.

Measures and analysis. The primary outcomes of this study were changes in BP and weight (measured using an automatic digital sphygmomanometer and an electronic scale), and the secondary outcomes were changes in body composition (assessed by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scanning), as well as glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and blood lipids after 6 months. All outcome measures were recorded at baseline and at each monthly visit. Incidence rates of hypoglycemia were based on blood glucose (defined as blood glucose < 70 mg/dL) and/or symptomatic hypoglycemia (symptoms of sweating, paleness, dizziness, and confusion). Two cardiologists who were blind to the patients’ diet condition measured and recorded all pertinent clinical parameters and adjudicated serious adverse events.

Data were compared using independent-samples t-tests or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorial variables as appropriate. Repeated-measures ANOVA via a linear mixed model was employed to test the effects of diet, time, and their interaction. In subgroup analyses, differential effects of the intervention on the primary outcomes were evaluated with respect to patients’ level of education, domicile, and sex based on the statistical significance of the interaction term for the subgroup of interest in the multivariate model. Analyses were performed based on completers and on an intention-to-treat principle.

Main results. Among the 205 randomized participants, 118 were women and 87 were men; mean (SD) age was 50.5 (8.8) years; mean (SD) BMI was 28.7 (2.6); mean (SD) SBP was 143 (10) mmHg; and mean (SD) DBP was 91 (9) mmHg. At the end of the 6-month intervention, 173 (84.4%) completed the study (IER group: n = 88; CER group: n = 85). Both groups had similar dropout rates at 6 months (IER group: 14 participants [13.7%]; CER group: 18 participants [17.5%]; P = .83) and were well matched for baseline characteristics except for triglyceride levels.

In the completers analysis, both groups experienced significant reductions in weight (mean [SEM]), but there was no difference between treatment groups (−7.2 [0.6] kg in the IER group vs −7.1 [0.6] kg in the CER group; diet by time P = .72). Similarly, the change in SBP and DBP achieved was statistically significant over time, but there was also no difference between the dietary interventions (−8 [0.7] mmHg in the IER group vs −8 [0.6] mmHg in the CER group, diet by time P = .68; −6 [0.6] mmHg in the IER group vs −6 [0.5] mmHg in the CER group, diet by time P = .53]. Subgroup analyses of the association of the intervention with weight, SBP and DBP by sex, education, and domicile showed no significant between-group differences.

All measures of body composition decreased significantly at 6 months with both groups experiencing comparable reductions in total fat mass (−5.5 [0.6] kg in the IER group vs −4.8 [0.5] kg in the CER group, diet by time P = .08) and android fat mass (−1.1 [0.2] kg in the IER group vs −0.8 [0.2] kg in the CER group, diet by time P = .16). Of note, participants in the CER group lost significantly more total fat-free mass than did participants in the IER group (mean [SEM], −2.3 [0.2] kg vs −1.7 [0.2] kg; P = .03], and there was a trend toward a greater change in total fat mass in the IER group (P = .08). The secondary outcome of mean (SEM) HbA1c (−0.2% [0.1%]) and blood lipid levels (triglyceride level, −1.0 [0.3] mmol/L; total cholesterol level, −0.9 [0.2] mmol/L; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, −0.9 [0.2 mmol/L; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level, 0.7 [0.3] mmol/L] improved with weight loss (P < .05), with no differences between groups (diet by time P > .05).

The intention-to-treat analysis demonstrated that IER and CER are equally effective for weight loss and blood pressure control: both groups experienced significant reductions in weight, SBP, and DBP, but with no difference between treatment groups – mean (SEM) weight change with IER was −7.0 (0.6) kg vs −6.8 (0.6) kg with CER; the mean (SEM) SBP with IER was −7 (0.7) mmHg vs −7 (0.6) mmHg with CER; and the mean (SEM) DBP with IER was −6 (0.5) mmHg vs −5 (0.5) mmHg with CER, (diet by time P = .62, .39, and .41, respectively). There were favorable improvements in

Conclusion. A 2-day severe energy restriction with 5 days of habitual eating compared to 7 days of CER provides an acceptable alternative for BP control and weight loss in overweight and obese individuals with hypertension after 6 months. IER may offer a useful alternative strategy for this population, who find continuous weight-loss diets too difficult to maintain.

Commentary

Globally, obesity represents a major health challenge as it substantially increases the risk of diseases such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease.1 Lifestyle modifications, including weight loss and increased physical activity, are recommended in major guidelines as a first-step intervention in the treatment of hypertensive patients.2 However, lifestyle and behavioral interventions aimed at reducing calorie intake through low-calorie dieting is challenging as it is dependent on individual motivation and adherence to a strict, continuous protocol. Further, CER strategies have limited effectiveness because complex and persistent hormonal, metabolic, and neurochemical adaptations defend against weight loss and promote weight regain.3-4 IER has drawn attention in the popular media as an alternative to CER due to its feasibility and even potential for higher rates of compliance.5

This study adds to the literature as it is the first randomized controlled trial (to the knowledge of the authors at the time of publication) to explore 2 forms of energy restriction – CER and IER – and their impact on weight loss, BP, body composition, HbA1c, and blood lipid levels in overweight and obese patients with high blood pressure. Results from this study showed that IER is as effective as, but not superior to, CER (in terms of the outcomes measures assessed). Specifically, findings highlighted that the 5:2 diet is an effective strategy and noninferior to that of daily calorie restriction for BP and weight control. In addition, both weight loss and BP reduction were greater in a subgroup of obese compared with overweight participants, which indicates that obese populations may benefit more from energy restriction. As the authors highlight, this study both aligns with and expands on current related literature.

This study has both strengths and limitations, especially with regard to the design and data analysis strategy. A key strength is the randomized controlled trial design which enables increased internal validity and decreases several sources of bias, including selection bias and confounding. In addition, it was also designed as a pragmatic trial, with the protocol reflecting efforts to replicate the real-world environment by not supplying meal replacements or food. Notably, only 9 patients could not comply with the protocol, indicating that acceptability of the diet protocol was high. However, as this was only a 6-month long study, further studies are needed to determine whether a 5:2 diet is sustainable (and effective) in the long-term compared with CER, which the authors highlight. The study was also adequately powered to detect clinically meaningful differences in weight loss and SBP, and appropriate analyses were performed on both the basis of completers and on an intention-to-treat principle. However, further studies are needed that are adequately powered to also detect clinically meaningful differences in the other measures, ie, body composition, HbA1c, and blood lipid levels. Importantly, generalizability of findings from this study is limited as the study population comprises only Chinese adults, predominately middle-aged, overweight, and had mildly to moderately elevated SBP and DBP, and excluded diabetic patients. Thus, findings are not necessarily applicable to individuals with highly elevated blood pressure or poorly controlled diabetes.

Applications for Clinical Practice

Results of this study demonstrated that IER is an effective alternative diet strategy for weight loss and blood pressure control in overweight and obese patients with hypertension and is comparable to CER. This is relevant for clinical practice as IER may be easier to maintain in this population compared to continuous weight-loss diets. Importantly, both types of calorie restriction require clinical oversight as medication changes and periodic monitoring of hypotensive and hypoglycemic episodes are needed. Clinicians should consider what is feasible and sustainable for their patients when recommending intermittent energy restriction.

Financial disclosures: None.

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the effects of intermittent energy restriction (IER) with those of continuous energy restriction (CER) on blood pressure control and weight loss in overweight and obese patients with hypertension during a 6-month period.

Design. Randomized controlled trial.

Settings and participants. The trial was conducted at the Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University from June 1, 2020, to April 30, 2021. Chinese adults were recruited using advertisements and flyers posted in the hospital and local communities. Prior to participation in study activities, all participants gave informed consent prior to recruitment and were provided compensation in the form of a $38 voucher at 3 and 6 months for their time for participating in the study.

The main inclusion criteria were patients between the ages of 18 and 70 years, hypertension, and body mass index (BMI) ranging from 24 to 40 kg/m2. The exclusion criteria were systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 120 mmHg, type 1 or 2 diabetes with a history of severe hypoglycemic episodes, pregnancy or breastfeeding, usage of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, weight loss > 5 kg within the past 3 months or previous weight loss surgery, and inability to adhere to the dietary protocol.

Of the 294 participants screened for eligibility, 205 were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the IER group (n = 102) or the CER group (n = 103), stratified by sex and BMI (as overweight or obese). All participants were required to have a stable medication regimen and weight in the 3 months prior to enrollment and not to use weight-loss drugs or vitamin supplements for the duration of the study. Researchers and participants were not blinded to the study group assignment.

Interventions. Participants randomly assigned to the IER group followed a 5:2 eating pattern: a very-low-energy diet of 500-600 kcal for 2 days of the week along with their usual diet for the other 5 days. The 2 days of calorie restriction could be consecutive or nonconsecutive, with a minimum of 0.8 g supplemental protein per kg of body weight per day, in accordance with the 2016 Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents. The CER group was advised to consume 1000 kcal/day for women and 1200 kcal/day for men on a 7-day energy restriction. That is, they were prescribed a daily 25% restriction based on the general principles of a Mediterranean-type diet (30% fat, 45-50% carbohydrate, and 20-25% protein).

Both groups received dietary education from a qualified dietitian and were recommended to maintain their current daily activity levels throughout the trial. Written dietary information brochures with portion advice and sample meal plans were provided to improve compliance in each group. All participants received a digital cooking scale to weigh foods to ensure accuracy of intake and were required to keep a food diary while following the recommended recipe on 2 days/week during calorie restriction to help with adherence. No food was provided. All participants were followed up by regular outpatient visits to both cardiologists and dietitians once a month. Diet checklists, activity schedules, and weight were reviewed to assess compliance with dietary advice at each visit.

Of note, participants were encouraged to measure and record their BP twice daily, and if 2 consecutive BP readings were < 110/70 mmHg and/or accompanied by hypotensive episodes with symptoms (dizziness, nausea, headache, and fatigue), they were asked to contact the investigators directly. Antihypertensive medication changes were then made in consultation with cardiologists. In addition, a medication management protocol (ie, doses of antidiabetic medications, including insulin and sulfonylurea) was designed to avoid hypoglycemia. Medication could be reduced in the CER group based on the basal dose at the endocrinologist’s discretion. In the IER group, insulin and sulfonylureas were discontinued on calorie restriction days only, and long-acting insulin was discontinued the night before the IER day. Insulin was not to be resumed until a full day’s caloric intake was achieved.

Measures and analysis. The primary outcomes of this study were changes in BP and weight (measured using an automatic digital sphygmomanometer and an electronic scale), and the secondary outcomes were changes in body composition (assessed by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scanning), as well as glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and blood lipids after 6 months. All outcome measures were recorded at baseline and at each monthly visit. Incidence rates of hypoglycemia were based on blood glucose (defined as blood glucose < 70 mg/dL) and/or symptomatic hypoglycemia (symptoms of sweating, paleness, dizziness, and confusion). Two cardiologists who were blind to the patients’ diet condition measured and recorded all pertinent clinical parameters and adjudicated serious adverse events.

Data were compared using independent-samples t-tests or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorial variables as appropriate. Repeated-measures ANOVA via a linear mixed model was employed to test the effects of diet, time, and their interaction. In subgroup analyses, differential effects of the intervention on the primary outcomes were evaluated with respect to patients’ level of education, domicile, and sex based on the statistical significance of the interaction term for the subgroup of interest in the multivariate model. Analyses were performed based on completers and on an intention-to-treat principle.

Main results. Among the 205 randomized participants, 118 were women and 87 were men; mean (SD) age was 50.5 (8.8) years; mean (SD) BMI was 28.7 (2.6); mean (SD) SBP was 143 (10) mmHg; and mean (SD) DBP was 91 (9) mmHg. At the end of the 6-month intervention, 173 (84.4%) completed the study (IER group: n = 88; CER group: n = 85). Both groups had similar dropout rates at 6 months (IER group: 14 participants [13.7%]; CER group: 18 participants [17.5%]; P = .83) and were well matched for baseline characteristics except for triglyceride levels.

In the completers analysis, both groups experienced significant reductions in weight (mean [SEM]), but there was no difference between treatment groups (−7.2 [0.6] kg in the IER group vs −7.1 [0.6] kg in the CER group; diet by time P = .72). Similarly, the change in SBP and DBP achieved was statistically significant over time, but there was also no difference between the dietary interventions (−8 [0.7] mmHg in the IER group vs −8 [0.6] mmHg in the CER group, diet by time P = .68; −6 [0.6] mmHg in the IER group vs −6 [0.5] mmHg in the CER group, diet by time P = .53]. Subgroup analyses of the association of the intervention with weight, SBP and DBP by sex, education, and domicile showed no significant between-group differences.