User login

Bariatric surgery may cut cancer in obesity with liver disease

In a large cohort of insured working adults with severe obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the rate of incident cancer was lower during a 10-month median follow-up period among those who underwent bariatric surgery. The rate was especially lower with regard to obesity-related cancers. The risk reduction was greater among patients with cirrhosis.

Among almost 100,000 patients with severe obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2) and NAFLD, those who underwent bariatric surgery had an 18% and 35% lower risk of developing any cancer or obesity-related cancer, respectively.

Bariatric surgery was associated with a significantly lower risk of being diagnosed with colorectal, pancreatic, endometrial, and thyroid cancer, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma and multiple myeloma (all obesity-related cancers). The findings are from an observational study by Vinod K. Rustgi, MD, MBA, and colleagues, which was published online March 17, 2021, in Gastroenterology.

It was not surprising that bariatric surgery is effective in reducing the malignancy rate among patients with cirrhosis, the researchers wrote, because the surgery results in long-term weight loss, resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and regression of fibrosis.

“Cirrhosis can happen from fatty liver disease or NASH,” Dr. Rustgi, a hepatologist at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., explained to this news organization. “It’s becoming the fastest growing indication for liver transplant, but also the reason for increased rates of hepatocellular carcinoma.”

Current treatment for patients with obesity and fatty liver disease begins with lifestyle changes to lose weight, he continued. “As people lose 10% of their weight, they actually start to see regression of fibrosis in the liver that is correlated with [lower rates of] malignancy outcomes and other deleterious outcomes.” But long-lasting weight loss is extremely difficult to achieve.

Future studies “may identify new targets and treatments, such as antidiabetic-, satiety-, or GLP-1-based medications, for chemoprevention in NAFLD/NASH,” the investigators suggested. However, pharmaceutical agents will likely be very expensive when they eventually get marketed, Dr. Rustgi observed.

Although “bariatric surgery is a more aggressive approach than lifestyle modifications, surgery may provide additional benefits, such as improved quality of life and decreased long-term health care costs,” he and his coauthors concluded.

Rising rates of fatty liver disease, obesity

An estimated 30% of the population of the United States has NAFLD, the most common chronic liver disease, the researchers noted in their article. The prevalence of NAFLD increased 2.8-fold in the United States between 2003 and 2011, in parallel with increasing obesity.

NAFLD is more common among male patients with obesity and diabetes and Hispanic patients; “70% of [patients with diabetes] may have fatty liver disease, according to certain surveys,” Dr. Rustgi noted.

Cancer is the second greatest cause of mortality among patients with obesity and NAFLD, he continued, after cardiovascular disease. Cancer mortality is higher than mortality from liver disease.

Obesity-related cancers include adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, cancers of the breast (in postmenopausal women), colon, rectum, endometrium (corpus uterus), gallbladder, gastric cardia, kidney (renal cell), liver, ovary, pancreas, and thyroid, as well as meningioma and multiple myeloma, according to a 2016 report from the International Agency for Research on Cancer working group.

Obesity-related cancer accounted for 40% of all cancer in the United States in 2014 – 55% of cancers in women, and 24% of cancers in men, according to a study published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 2017, as previously reported by this news organization.

Several studies, including one presented at Obesity Week in 2019 and later published, have shown that bariatric surgery is linked with a lower risk for cancer in general populations.

One meta-analysis reported that NAFLD is an independent risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal, breast, gastric, pancreatic, prostate, and esophageal cancers. In another study, NAFLD was associated with a twofold increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and uterine, stomach, pancreatic, and colon cancers, Dr. Rustgi and colleagues noted.

Until now, the impact of bariatric surgery on the risk for cancer among patients with obesity and NAFLD was unknown.

Does bariatric surgery curb cancer risk in liver disease?

The researchers examined insurance claims data from the national MarketScan database from Jan. 1, 2007, to Dec. 31, 2017, for patients aged 18-64 years who had health insurance from 350 employers and 100 insurers. They identified 98,090 patients with severe obesity who were newly diagnosed with NAFLD during 2008-2017.

Roughly a third of the cohort (33,435 patients) underwent bariatric surgery. From 2008 to 2017, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies increased from 4% of bariatric procedures to 68% of all surgeries. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures fell from 35% to less than 1% and from 49% to 28%, respectively.

Patients who underwent bariatric surgery were younger (mean age, 44 vs. 46 years), were more likely to be women (74% vs. 62%), and were less likely to have a history of smoking (6% vs. 10%).

During a mean follow-up of 22 months (and a median follow-up of 10 months), there were 911 incident cases of obesity-related cancers. These included cancer of the colon (116 cases), rectum (15), breast (in postmenopausal women; 131), kidney (120), esophagus (16), gastric cardia (8), gallbladder (4), pancreas (44), ovaries (74), endometrium (135), and thyroid (143), as well as hepatocellular carcinoma (49), multiple myeloma (50), and meningioma (6). There were 1,912 incident cases of other cancers, such as brain and lung cancers and leukemia.

A total of 258 patients who underwent bariatric surgery developed an obesity-related cancer (an incidence of 3.83 per 1,000 person-years), compared with 653 patients who did not have bariatric surgery (an incidence of 5.63 per 1,000 person-years).

The researchers noted that study limitations include the fact that it was restricted to privately insured individuals aged 18-64 years with severe obesity. In addition, “the short median follow-up may underestimate the full effect of bariatric surgery on cancer risk,” they wrote.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large cohort of insured working adults with severe obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the rate of incident cancer was lower during a 10-month median follow-up period among those who underwent bariatric surgery. The rate was especially lower with regard to obesity-related cancers. The risk reduction was greater among patients with cirrhosis.

Among almost 100,000 patients with severe obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2) and NAFLD, those who underwent bariatric surgery had an 18% and 35% lower risk of developing any cancer or obesity-related cancer, respectively.

Bariatric surgery was associated with a significantly lower risk of being diagnosed with colorectal, pancreatic, endometrial, and thyroid cancer, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma and multiple myeloma (all obesity-related cancers). The findings are from an observational study by Vinod K. Rustgi, MD, MBA, and colleagues, which was published online March 17, 2021, in Gastroenterology.

It was not surprising that bariatric surgery is effective in reducing the malignancy rate among patients with cirrhosis, the researchers wrote, because the surgery results in long-term weight loss, resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and regression of fibrosis.

“Cirrhosis can happen from fatty liver disease or NASH,” Dr. Rustgi, a hepatologist at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., explained to this news organization. “It’s becoming the fastest growing indication for liver transplant, but also the reason for increased rates of hepatocellular carcinoma.”

Current treatment for patients with obesity and fatty liver disease begins with lifestyle changes to lose weight, he continued. “As people lose 10% of their weight, they actually start to see regression of fibrosis in the liver that is correlated with [lower rates of] malignancy outcomes and other deleterious outcomes.” But long-lasting weight loss is extremely difficult to achieve.

Future studies “may identify new targets and treatments, such as antidiabetic-, satiety-, or GLP-1-based medications, for chemoprevention in NAFLD/NASH,” the investigators suggested. However, pharmaceutical agents will likely be very expensive when they eventually get marketed, Dr. Rustgi observed.

Although “bariatric surgery is a more aggressive approach than lifestyle modifications, surgery may provide additional benefits, such as improved quality of life and decreased long-term health care costs,” he and his coauthors concluded.

Rising rates of fatty liver disease, obesity

An estimated 30% of the population of the United States has NAFLD, the most common chronic liver disease, the researchers noted in their article. The prevalence of NAFLD increased 2.8-fold in the United States between 2003 and 2011, in parallel with increasing obesity.

NAFLD is more common among male patients with obesity and diabetes and Hispanic patients; “70% of [patients with diabetes] may have fatty liver disease, according to certain surveys,” Dr. Rustgi noted.

Cancer is the second greatest cause of mortality among patients with obesity and NAFLD, he continued, after cardiovascular disease. Cancer mortality is higher than mortality from liver disease.

Obesity-related cancers include adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, cancers of the breast (in postmenopausal women), colon, rectum, endometrium (corpus uterus), gallbladder, gastric cardia, kidney (renal cell), liver, ovary, pancreas, and thyroid, as well as meningioma and multiple myeloma, according to a 2016 report from the International Agency for Research on Cancer working group.

Obesity-related cancer accounted for 40% of all cancer in the United States in 2014 – 55% of cancers in women, and 24% of cancers in men, according to a study published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 2017, as previously reported by this news organization.

Several studies, including one presented at Obesity Week in 2019 and later published, have shown that bariatric surgery is linked with a lower risk for cancer in general populations.

One meta-analysis reported that NAFLD is an independent risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal, breast, gastric, pancreatic, prostate, and esophageal cancers. In another study, NAFLD was associated with a twofold increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and uterine, stomach, pancreatic, and colon cancers, Dr. Rustgi and colleagues noted.

Until now, the impact of bariatric surgery on the risk for cancer among patients with obesity and NAFLD was unknown.

Does bariatric surgery curb cancer risk in liver disease?

The researchers examined insurance claims data from the national MarketScan database from Jan. 1, 2007, to Dec. 31, 2017, for patients aged 18-64 years who had health insurance from 350 employers and 100 insurers. They identified 98,090 patients with severe obesity who were newly diagnosed with NAFLD during 2008-2017.

Roughly a third of the cohort (33,435 patients) underwent bariatric surgery. From 2008 to 2017, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies increased from 4% of bariatric procedures to 68% of all surgeries. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures fell from 35% to less than 1% and from 49% to 28%, respectively.

Patients who underwent bariatric surgery were younger (mean age, 44 vs. 46 years), were more likely to be women (74% vs. 62%), and were less likely to have a history of smoking (6% vs. 10%).

During a mean follow-up of 22 months (and a median follow-up of 10 months), there were 911 incident cases of obesity-related cancers. These included cancer of the colon (116 cases), rectum (15), breast (in postmenopausal women; 131), kidney (120), esophagus (16), gastric cardia (8), gallbladder (4), pancreas (44), ovaries (74), endometrium (135), and thyroid (143), as well as hepatocellular carcinoma (49), multiple myeloma (50), and meningioma (6). There were 1,912 incident cases of other cancers, such as brain and lung cancers and leukemia.

A total of 258 patients who underwent bariatric surgery developed an obesity-related cancer (an incidence of 3.83 per 1,000 person-years), compared with 653 patients who did not have bariatric surgery (an incidence of 5.63 per 1,000 person-years).

The researchers noted that study limitations include the fact that it was restricted to privately insured individuals aged 18-64 years with severe obesity. In addition, “the short median follow-up may underestimate the full effect of bariatric surgery on cancer risk,” they wrote.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a large cohort of insured working adults with severe obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the rate of incident cancer was lower during a 10-month median follow-up period among those who underwent bariatric surgery. The rate was especially lower with regard to obesity-related cancers. The risk reduction was greater among patients with cirrhosis.

Among almost 100,000 patients with severe obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2) and NAFLD, those who underwent bariatric surgery had an 18% and 35% lower risk of developing any cancer or obesity-related cancer, respectively.

Bariatric surgery was associated with a significantly lower risk of being diagnosed with colorectal, pancreatic, endometrial, and thyroid cancer, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma and multiple myeloma (all obesity-related cancers). The findings are from an observational study by Vinod K. Rustgi, MD, MBA, and colleagues, which was published online March 17, 2021, in Gastroenterology.

It was not surprising that bariatric surgery is effective in reducing the malignancy rate among patients with cirrhosis, the researchers wrote, because the surgery results in long-term weight loss, resolution of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and regression of fibrosis.

“Cirrhosis can happen from fatty liver disease or NASH,” Dr. Rustgi, a hepatologist at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., explained to this news organization. “It’s becoming the fastest growing indication for liver transplant, but also the reason for increased rates of hepatocellular carcinoma.”

Current treatment for patients with obesity and fatty liver disease begins with lifestyle changes to lose weight, he continued. “As people lose 10% of their weight, they actually start to see regression of fibrosis in the liver that is correlated with [lower rates of] malignancy outcomes and other deleterious outcomes.” But long-lasting weight loss is extremely difficult to achieve.

Future studies “may identify new targets and treatments, such as antidiabetic-, satiety-, or GLP-1-based medications, for chemoprevention in NAFLD/NASH,” the investigators suggested. However, pharmaceutical agents will likely be very expensive when they eventually get marketed, Dr. Rustgi observed.

Although “bariatric surgery is a more aggressive approach than lifestyle modifications, surgery may provide additional benefits, such as improved quality of life and decreased long-term health care costs,” he and his coauthors concluded.

Rising rates of fatty liver disease, obesity

An estimated 30% of the population of the United States has NAFLD, the most common chronic liver disease, the researchers noted in their article. The prevalence of NAFLD increased 2.8-fold in the United States between 2003 and 2011, in parallel with increasing obesity.

NAFLD is more common among male patients with obesity and diabetes and Hispanic patients; “70% of [patients with diabetes] may have fatty liver disease, according to certain surveys,” Dr. Rustgi noted.

Cancer is the second greatest cause of mortality among patients with obesity and NAFLD, he continued, after cardiovascular disease. Cancer mortality is higher than mortality from liver disease.

Obesity-related cancers include adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, cancers of the breast (in postmenopausal women), colon, rectum, endometrium (corpus uterus), gallbladder, gastric cardia, kidney (renal cell), liver, ovary, pancreas, and thyroid, as well as meningioma and multiple myeloma, according to a 2016 report from the International Agency for Research on Cancer working group.

Obesity-related cancer accounted for 40% of all cancer in the United States in 2014 – 55% of cancers in women, and 24% of cancers in men, according to a study published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in 2017, as previously reported by this news organization.

Several studies, including one presented at Obesity Week in 2019 and later published, have shown that bariatric surgery is linked with a lower risk for cancer in general populations.

One meta-analysis reported that NAFLD is an independent risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal, breast, gastric, pancreatic, prostate, and esophageal cancers. In another study, NAFLD was associated with a twofold increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma and uterine, stomach, pancreatic, and colon cancers, Dr. Rustgi and colleagues noted.

Until now, the impact of bariatric surgery on the risk for cancer among patients with obesity and NAFLD was unknown.

Does bariatric surgery curb cancer risk in liver disease?

The researchers examined insurance claims data from the national MarketScan database from Jan. 1, 2007, to Dec. 31, 2017, for patients aged 18-64 years who had health insurance from 350 employers and 100 insurers. They identified 98,090 patients with severe obesity who were newly diagnosed with NAFLD during 2008-2017.

Roughly a third of the cohort (33,435 patients) underwent bariatric surgery. From 2008 to 2017, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies increased from 4% of bariatric procedures to 68% of all surgeries. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedures fell from 35% to less than 1% and from 49% to 28%, respectively.

Patients who underwent bariatric surgery were younger (mean age, 44 vs. 46 years), were more likely to be women (74% vs. 62%), and were less likely to have a history of smoking (6% vs. 10%).

During a mean follow-up of 22 months (and a median follow-up of 10 months), there were 911 incident cases of obesity-related cancers. These included cancer of the colon (116 cases), rectum (15), breast (in postmenopausal women; 131), kidney (120), esophagus (16), gastric cardia (8), gallbladder (4), pancreas (44), ovaries (74), endometrium (135), and thyroid (143), as well as hepatocellular carcinoma (49), multiple myeloma (50), and meningioma (6). There were 1,912 incident cases of other cancers, such as brain and lung cancers and leukemia.

A total of 258 patients who underwent bariatric surgery developed an obesity-related cancer (an incidence of 3.83 per 1,000 person-years), compared with 653 patients who did not have bariatric surgery (an incidence of 5.63 per 1,000 person-years).

The researchers noted that study limitations include the fact that it was restricted to privately insured individuals aged 18-64 years with severe obesity. In addition, “the short median follow-up may underestimate the full effect of bariatric surgery on cancer risk,” they wrote.

The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is the answer to childhood obesity

There is no question that none of us, not just pediatricians, is doing a very good job of dealing with the obesity problem this nation faces. We can agree that a more active lifestyle that includes spells of vigorous activity is important for weight management. We know that in general overweight people sleep less than do those whose basal metabolic rate is normal. And, of course, we know that a diet high in calorie-dense foods is associated with unhealthy weight gain.

Not surprisingly, overweight individuals are usually struggling with all three of these challenges. They are less active, get too little sleep, and are ingesting a diet that is too calorie dense. In other words, they would benefit from a total lifestyle reboot. But you know as well as I do a change of that magnitude is much easier said than done. Few families can afford nor would they have the appetite for sending their children to a “fat camp” for 6 months with no guarantee of success.

Instead of throwing up our hands in the face of this monumental task or attacking it at close range, maybe we should aim our efforts at the risk associations that will yield the best results for our efforts. A group of researchers at the University of South Australia has just published a study in Pediatrics in which they provide some data that may help us target our interventions with obese and overweight children. The researchers did not investigate diet, but used accelerometers to determine how much time each child spent sleeping and a variety of activity levels. They then determined what effect changes in the child’s allocation of activity had on their adiposity.

The investigators found on a minute-to-minute basis that an increase in a child’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was up to six times more effective at influencing adiposity than was a decrease in sedentary time or an increase in sleep duration. For example, 17 minutes of MVPA had the same beneficial effect as 52 minutes more sleep or 56 minutes less sedentary time. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the researchers found that light activity was positively associated with adiposity.

For those of us in primary care, this study from Australia suggests that our time (and the parents’ time) would be best spent figuring out how to include more MVPA in the child’s day and not focus so much on sleep duration and sedentary intervals.

However, before one can make any recommendation one must first have a clear understanding of how the child and his family spend the day. This process can be done in the office by interviewing the family. I have found that this is not as time consuming as one might think and often yields some valuable additional insight into the family’s dynamics. Sending the family home with an hourly log to be filled in or asking them to use a smartphone to record information will also work.

I must admit that at first I found the results of this study ran counter to my intuition. I have always felt that sleep is the linchpin to the solution of a variety of health style related problems. In my construct, more sleep has always been the first and easy answer and decreasing screen time the second. But, it turns out that increasing MVPA may give us the biggest bang for the buck. Which is fine with me.

The problem facing us is how we can be creative in adding that 20 minutes of vigorous activity. In most communities, we have allowed the school system to drop the ball. We can hope that this study will be confirmed or at least widely publicized. It feels like it is time to guarantee that every child gets a robust gym class every school day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

There is no question that none of us, not just pediatricians, is doing a very good job of dealing with the obesity problem this nation faces. We can agree that a more active lifestyle that includes spells of vigorous activity is important for weight management. We know that in general overweight people sleep less than do those whose basal metabolic rate is normal. And, of course, we know that a diet high in calorie-dense foods is associated with unhealthy weight gain.

Not surprisingly, overweight individuals are usually struggling with all three of these challenges. They are less active, get too little sleep, and are ingesting a diet that is too calorie dense. In other words, they would benefit from a total lifestyle reboot. But you know as well as I do a change of that magnitude is much easier said than done. Few families can afford nor would they have the appetite for sending their children to a “fat camp” for 6 months with no guarantee of success.

Instead of throwing up our hands in the face of this monumental task or attacking it at close range, maybe we should aim our efforts at the risk associations that will yield the best results for our efforts. A group of researchers at the University of South Australia has just published a study in Pediatrics in which they provide some data that may help us target our interventions with obese and overweight children. The researchers did not investigate diet, but used accelerometers to determine how much time each child spent sleeping and a variety of activity levels. They then determined what effect changes in the child’s allocation of activity had on their adiposity.

The investigators found on a minute-to-minute basis that an increase in a child’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was up to six times more effective at influencing adiposity than was a decrease in sedentary time or an increase in sleep duration. For example, 17 minutes of MVPA had the same beneficial effect as 52 minutes more sleep or 56 minutes less sedentary time. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the researchers found that light activity was positively associated with adiposity.

For those of us in primary care, this study from Australia suggests that our time (and the parents’ time) would be best spent figuring out how to include more MVPA in the child’s day and not focus so much on sleep duration and sedentary intervals.

However, before one can make any recommendation one must first have a clear understanding of how the child and his family spend the day. This process can be done in the office by interviewing the family. I have found that this is not as time consuming as one might think and often yields some valuable additional insight into the family’s dynamics. Sending the family home with an hourly log to be filled in or asking them to use a smartphone to record information will also work.

I must admit that at first I found the results of this study ran counter to my intuition. I have always felt that sleep is the linchpin to the solution of a variety of health style related problems. In my construct, more sleep has always been the first and easy answer and decreasing screen time the second. But, it turns out that increasing MVPA may give us the biggest bang for the buck. Which is fine with me.

The problem facing us is how we can be creative in adding that 20 minutes of vigorous activity. In most communities, we have allowed the school system to drop the ball. We can hope that this study will be confirmed or at least widely publicized. It feels like it is time to guarantee that every child gets a robust gym class every school day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

There is no question that none of us, not just pediatricians, is doing a very good job of dealing with the obesity problem this nation faces. We can agree that a more active lifestyle that includes spells of vigorous activity is important for weight management. We know that in general overweight people sleep less than do those whose basal metabolic rate is normal. And, of course, we know that a diet high in calorie-dense foods is associated with unhealthy weight gain.

Not surprisingly, overweight individuals are usually struggling with all three of these challenges. They are less active, get too little sleep, and are ingesting a diet that is too calorie dense. In other words, they would benefit from a total lifestyle reboot. But you know as well as I do a change of that magnitude is much easier said than done. Few families can afford nor would they have the appetite for sending their children to a “fat camp” for 6 months with no guarantee of success.

Instead of throwing up our hands in the face of this monumental task or attacking it at close range, maybe we should aim our efforts at the risk associations that will yield the best results for our efforts. A group of researchers at the University of South Australia has just published a study in Pediatrics in which they provide some data that may help us target our interventions with obese and overweight children. The researchers did not investigate diet, but used accelerometers to determine how much time each child spent sleeping and a variety of activity levels. They then determined what effect changes in the child’s allocation of activity had on their adiposity.

The investigators found on a minute-to-minute basis that an increase in a child’s moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was up to six times more effective at influencing adiposity than was a decrease in sedentary time or an increase in sleep duration. For example, 17 minutes of MVPA had the same beneficial effect as 52 minutes more sleep or 56 minutes less sedentary time. Interestingly and somewhat surprisingly, the researchers found that light activity was positively associated with adiposity.

For those of us in primary care, this study from Australia suggests that our time (and the parents’ time) would be best spent figuring out how to include more MVPA in the child’s day and not focus so much on sleep duration and sedentary intervals.

However, before one can make any recommendation one must first have a clear understanding of how the child and his family spend the day. This process can be done in the office by interviewing the family. I have found that this is not as time consuming as one might think and often yields some valuable additional insight into the family’s dynamics. Sending the family home with an hourly log to be filled in or asking them to use a smartphone to record information will also work.

I must admit that at first I found the results of this study ran counter to my intuition. I have always felt that sleep is the linchpin to the solution of a variety of health style related problems. In my construct, more sleep has always been the first and easy answer and decreasing screen time the second. But, it turns out that increasing MVPA may give us the biggest bang for the buck. Which is fine with me.

The problem facing us is how we can be creative in adding that 20 minutes of vigorous activity. In most communities, we have allowed the school system to drop the ball. We can hope that this study will be confirmed or at least widely publicized. It feels like it is time to guarantee that every child gets a robust gym class every school day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Integrating primary care into a community mental health center

THE CASE

John C* is a 57-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and schizophrenia who followed up with a psychiatrist monthly at the community mental health center (CMHC). He had no primary care doctor. His psychiatrist referred him to our new Integrated Behavioral Health (IBH) clinic, also located in the CMHC, to see a family physician for complaints of urinary frequency, blurred vision, thirst, and weight loss. An on-site fingerstick revealed his blood glucose to be 357 mg/dL. Given the presumptive diagnosis of diabetes, we checked his bloodwork, prescribed metformin, and referred him for diabetes education. That evening, his lab results showed a hemoglobin A1C > 17%, a basic metabolic panel with an anion gap, ketones in the urine, and a low C-peptide level. We were unable to reach Mr. C by phone for further management.

● How would you proceed with this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Coordination of behavioral health and primary care can take many forms, from simple synchronized care via referral, to co-located services, to fully integrated care.1 Reverse integration, the subject of this article, is the provision of primary care in mental health or substance use disorder treatment settings. Published evidence to date regarding this model is minimal. This article describes our experience in developing a model of reverse integration in which family physicians and nurse practitioners are embedded in a CMHC with psychiatric providers, counselors, and social workers to jointly address physical and behavioral health care issues and address social determinants of health.

The rationale for reverse integration

Many individuals with serious mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, have rates of comorbid chronic physical health conditions that are higher than in the general population. These conditions include obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis.2 Outcomes in the SMI group are also considerably worse than in the general population. People with SMI have a demonstrated loss of up to 32 years of potential life per patient compared with the general-population average, primarily due to poor physical health.2 Maladaptive health behaviors such as poor diet, lack of physical activity, tobacco use, and substance use contribute to this increased mortality.2,3 Social determinants of poor health are more prevalent among individuals with SMI, and a relative inability to collaborate in one’s own health care due to psychiatric symptoms further exacerbates the challenges.

Many individuals with SMI receive psychiatric care, case management, counseling, and psychosocial services in CMHCs. Their psychiatric caregiver may be their only regular health care provider. Family physicians—who receive residency training in behavioral health and social determinants of health in community settings—are distinctively capable of improving overall health care outcomes of patients with SMI.

THE ADVANTAGES OF A REVERSE-INTEGRATION PRACTICE MODEL

Delivering primary care in a CMHC with a behavioral health team can benefit patients with SMI and be a satisfying practice for family physicians. Specifically, family physicians

- find that caring for complex patients can be less stressful because they benefit from the knowledge and resources of the CMHC team. The CMHC team offers case management, counseling, employment services, and housing assistance, so the primary care provider and patient are well supported.

- see fewer patients per hour due to higher visit complexity (and coding). In our experience, team-based care and additional time with patients make complex patient care more enjoyable and less frustrating.

- benefit from a situation in which patients feel safe because the CMHC support staff knows them well.

Continue to: Other benefits

Other benefits. When primary care is delivered in a CMHC, there are “huddles” and warm handoffs that allow for bidirectional collaboration and care coordination between the primary care and behavioral health teams in real time. In addition, family medicine residents, medical students, and other learners can be successfully included in an IBH clinic for patients with SMI. The behavioral health team provides the mentorship, education, and modelling of skills needed to work with this population, including limit-setting, empathy, patience, and motivational interviewing.

For their part, learners self-report increased comfort and interest in working with underserved populations and improved awareness of the social determinants of health after these experiences.4,5 Many patients at CMHCs are comfortable working with learners if continuity is maintained with a primary care provider.

Challenges we’ve faced, tips we can offer

For primary care providers, the unique workplace culture, terminology, and patient population encountered in a CMHC can be challenging. Also challenging can be the combining of things such as electronic medical records (EMRs).

Culture. The CMHC model focuses on team-based care spearheaded by case managers, in contrast to the traditional family medicine model wherein the physician coordinates services. Case managers provide assessments of client stability and readiness to be seen. They also attend primary care visits to support patient interactions, provide important psychosocial information, and assess adherence to care.

Terminology. It’s not always easy to shift to different terminology in this culture. Thus, orientation needs to address things such as the use of the word “patient,” rather than “client,” when charting.

Continue to: The complexities of the patient population

The complexities of the patient population. Many patients treated at a CMHC have a history of trauma, anxiety, and paranoia, requiring adjustments to exam practices such as using smaller speculums, providing more physical space, and offering to leave examination room doors open while patients are waiting.

In addition, individuals with SMI often have multiple health conditions, but they may become uncomfortable with physical closeness, grow tired of conversation, or feel overwhelmed when asked to complete multiple tasks in 1 visit. As a result, visits may need to be shorter and more frequent.

It’s also worth noting that, in our experience, CMHC patients may have a higher no-show rate than typical primary care clinics, requiring flexibility in scheduling. To fill vacant primary care time slots, our front desk staff uses strategies such as waiting lists and offering walk-in visits to patients who are on site for other services.

Ideally, IBH clinics use a single, fully integrated EMR, but this is not always possible. If the primary care and CMHC EMR systems do not connect, then record review and repeat documentation is needed, while care is taken to adhere to the confidentiality standards of a particular state.

Standards of care and state policies. Written standards of care, procedures, and accreditation in CMHCs rarely include provisions for common primary care practice, such as vaccines, in-clinic medications, and implements for simple procedures. To provide these services in our clinic, we ordered/stocked the needed supplies and instituted protocols that mirrored our other outpatient family medicine clinical sites.

Continue to: Some states may have...

Some states may have policies that prevent reimbursement for mental health and primary care services billed on the same day. Seeing a family physician and a psychiatry provider on the same day is convenient for patients and allows for collaboration between providers. But reimbursement rules can vary by state, so starting an IBH clinic like this requires research into local billing regulations.

WANT TO START AN INTEGRATED BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CLINIC?

Detailed instruction on starting a primary care clinic in a CMHC is beyond the scope of this article. However, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration provides guidance on integrating primary care services into a local CMHC.6 Start by performing a baseline needs assessment of the CMHC and its patients to help guide clinic design. Leadership buy-in is key.

Leadership must provide adequate time and financial and technological support. This includes identifying appropriate space for primary care, offering training on using the EMR, and obtaining support from Finance to develop a realistic and competent business plan with an appropriate budgetary runway for start-up. (This may include securing grants in the beginning.)

We recommend starting small and expanding slowly. Once the clinic is operational, formal pathways for good communication are necessary. This includes holding regular team meetings to develop and revise clinic workflows—eg, patient enrollment, protocols, and administrative procedures such as managing medications and vaccinations—as well as addressing space, staffing, and training issues that arise. The IBH transitional leadership structure must include clinicians from both primary care and behavioral health, support staff, and the administration. Finally, you need the right staff—people who are passionate, flexible, and interested in trying something new.

THE CASE

The next day, an outreach was made to the CMHC nurse, who had the case manager go to Mr. C’s house and bring him to the CMHC for education on insulin injection, glucometer use, and diabetes nutrition. Mr. C was prescribed long-acting insulin at bedtime; his metformin was stopped and he was monitored closely.

Continue to: Mr. C now calls...

Mr. C now calls the CMHC nurse every few weeks to report his blood sugar levels, have his insulin dose adjusted, or just say “hello.” He continues to see his psychiatrist every month and his family physician every 4 months. The team collaborates as issues arise. His diabetes has been well controlled for more than 3 years.

The IBH clinic has grown in number of patients and family medicine providers, is self-sustaining, and has expanded services to include hepatitis C treatment.

1. Rajesh R, Tampi R, Balachandran S. The case for behavioral health integration into primary care. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:278-284.

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. 2006. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Mortality%20and%20Morbidity%20Final%20Report%208.18.08_0.pdf

3. Dickerson F, Stallings, CR, Origoni AE, et al. Cigarette Smoking among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in routine clinical settings, 1999-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:44-50.

4. Raddock M, Antenucci C, Chrisman L. Innovative primary care training: caring for the urban underserved. Innovations in Education Poster Session, Case School of Medicine Annual Education Retreat, Cleveland, OH, March 3, 2016.

5. Berg K, Antenucci C, Raddock M, et al. Deciding to care: medical students and patients’ social circumstances. Poster: Annual meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making. Pittsburgh, PA. October 2017.

6. Heath B, Wise Romero P, and Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. Washington, D.C. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. March 2013. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.pcpcc.org/resource/standard-framework-levels-integrated-healthcare

THE CASE

John C* is a 57-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and schizophrenia who followed up with a psychiatrist monthly at the community mental health center (CMHC). He had no primary care doctor. His psychiatrist referred him to our new Integrated Behavioral Health (IBH) clinic, also located in the CMHC, to see a family physician for complaints of urinary frequency, blurred vision, thirst, and weight loss. An on-site fingerstick revealed his blood glucose to be 357 mg/dL. Given the presumptive diagnosis of diabetes, we checked his bloodwork, prescribed metformin, and referred him for diabetes education. That evening, his lab results showed a hemoglobin A1C > 17%, a basic metabolic panel with an anion gap, ketones in the urine, and a low C-peptide level. We were unable to reach Mr. C by phone for further management.

● How would you proceed with this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Coordination of behavioral health and primary care can take many forms, from simple synchronized care via referral, to co-located services, to fully integrated care.1 Reverse integration, the subject of this article, is the provision of primary care in mental health or substance use disorder treatment settings. Published evidence to date regarding this model is minimal. This article describes our experience in developing a model of reverse integration in which family physicians and nurse practitioners are embedded in a CMHC with psychiatric providers, counselors, and social workers to jointly address physical and behavioral health care issues and address social determinants of health.

The rationale for reverse integration

Many individuals with serious mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, have rates of comorbid chronic physical health conditions that are higher than in the general population. These conditions include obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis.2 Outcomes in the SMI group are also considerably worse than in the general population. People with SMI have a demonstrated loss of up to 32 years of potential life per patient compared with the general-population average, primarily due to poor physical health.2 Maladaptive health behaviors such as poor diet, lack of physical activity, tobacco use, and substance use contribute to this increased mortality.2,3 Social determinants of poor health are more prevalent among individuals with SMI, and a relative inability to collaborate in one’s own health care due to psychiatric symptoms further exacerbates the challenges.

Many individuals with SMI receive psychiatric care, case management, counseling, and psychosocial services in CMHCs. Their psychiatric caregiver may be their only regular health care provider. Family physicians—who receive residency training in behavioral health and social determinants of health in community settings—are distinctively capable of improving overall health care outcomes of patients with SMI.

THE ADVANTAGES OF A REVERSE-INTEGRATION PRACTICE MODEL

Delivering primary care in a CMHC with a behavioral health team can benefit patients with SMI and be a satisfying practice for family physicians. Specifically, family physicians

- find that caring for complex patients can be less stressful because they benefit from the knowledge and resources of the CMHC team. The CMHC team offers case management, counseling, employment services, and housing assistance, so the primary care provider and patient are well supported.

- see fewer patients per hour due to higher visit complexity (and coding). In our experience, team-based care and additional time with patients make complex patient care more enjoyable and less frustrating.

- benefit from a situation in which patients feel safe because the CMHC support staff knows them well.

Continue to: Other benefits

Other benefits. When primary care is delivered in a CMHC, there are “huddles” and warm handoffs that allow for bidirectional collaboration and care coordination between the primary care and behavioral health teams in real time. In addition, family medicine residents, medical students, and other learners can be successfully included in an IBH clinic for patients with SMI. The behavioral health team provides the mentorship, education, and modelling of skills needed to work with this population, including limit-setting, empathy, patience, and motivational interviewing.

For their part, learners self-report increased comfort and interest in working with underserved populations and improved awareness of the social determinants of health after these experiences.4,5 Many patients at CMHCs are comfortable working with learners if continuity is maintained with a primary care provider.

Challenges we’ve faced, tips we can offer

For primary care providers, the unique workplace culture, terminology, and patient population encountered in a CMHC can be challenging. Also challenging can be the combining of things such as electronic medical records (EMRs).

Culture. The CMHC model focuses on team-based care spearheaded by case managers, in contrast to the traditional family medicine model wherein the physician coordinates services. Case managers provide assessments of client stability and readiness to be seen. They also attend primary care visits to support patient interactions, provide important psychosocial information, and assess adherence to care.

Terminology. It’s not always easy to shift to different terminology in this culture. Thus, orientation needs to address things such as the use of the word “patient,” rather than “client,” when charting.

Continue to: The complexities of the patient population

The complexities of the patient population. Many patients treated at a CMHC have a history of trauma, anxiety, and paranoia, requiring adjustments to exam practices such as using smaller speculums, providing more physical space, and offering to leave examination room doors open while patients are waiting.

In addition, individuals with SMI often have multiple health conditions, but they may become uncomfortable with physical closeness, grow tired of conversation, or feel overwhelmed when asked to complete multiple tasks in 1 visit. As a result, visits may need to be shorter and more frequent.

It’s also worth noting that, in our experience, CMHC patients may have a higher no-show rate than typical primary care clinics, requiring flexibility in scheduling. To fill vacant primary care time slots, our front desk staff uses strategies such as waiting lists and offering walk-in visits to patients who are on site for other services.

Ideally, IBH clinics use a single, fully integrated EMR, but this is not always possible. If the primary care and CMHC EMR systems do not connect, then record review and repeat documentation is needed, while care is taken to adhere to the confidentiality standards of a particular state.

Standards of care and state policies. Written standards of care, procedures, and accreditation in CMHCs rarely include provisions for common primary care practice, such as vaccines, in-clinic medications, and implements for simple procedures. To provide these services in our clinic, we ordered/stocked the needed supplies and instituted protocols that mirrored our other outpatient family medicine clinical sites.

Continue to: Some states may have...

Some states may have policies that prevent reimbursement for mental health and primary care services billed on the same day. Seeing a family physician and a psychiatry provider on the same day is convenient for patients and allows for collaboration between providers. But reimbursement rules can vary by state, so starting an IBH clinic like this requires research into local billing regulations.

WANT TO START AN INTEGRATED BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CLINIC?

Detailed instruction on starting a primary care clinic in a CMHC is beyond the scope of this article. However, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration provides guidance on integrating primary care services into a local CMHC.6 Start by performing a baseline needs assessment of the CMHC and its patients to help guide clinic design. Leadership buy-in is key.

Leadership must provide adequate time and financial and technological support. This includes identifying appropriate space for primary care, offering training on using the EMR, and obtaining support from Finance to develop a realistic and competent business plan with an appropriate budgetary runway for start-up. (This may include securing grants in the beginning.)

We recommend starting small and expanding slowly. Once the clinic is operational, formal pathways for good communication are necessary. This includes holding regular team meetings to develop and revise clinic workflows—eg, patient enrollment, protocols, and administrative procedures such as managing medications and vaccinations—as well as addressing space, staffing, and training issues that arise. The IBH transitional leadership structure must include clinicians from both primary care and behavioral health, support staff, and the administration. Finally, you need the right staff—people who are passionate, flexible, and interested in trying something new.

THE CASE

The next day, an outreach was made to the CMHC nurse, who had the case manager go to Mr. C’s house and bring him to the CMHC for education on insulin injection, glucometer use, and diabetes nutrition. Mr. C was prescribed long-acting insulin at bedtime; his metformin was stopped and he was monitored closely.

Continue to: Mr. C now calls...

Mr. C now calls the CMHC nurse every few weeks to report his blood sugar levels, have his insulin dose adjusted, or just say “hello.” He continues to see his psychiatrist every month and his family physician every 4 months. The team collaborates as issues arise. His diabetes has been well controlled for more than 3 years.

The IBH clinic has grown in number of patients and family medicine providers, is self-sustaining, and has expanded services to include hepatitis C treatment.

THE CASE

John C* is a 57-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and schizophrenia who followed up with a psychiatrist monthly at the community mental health center (CMHC). He had no primary care doctor. His psychiatrist referred him to our new Integrated Behavioral Health (IBH) clinic, also located in the CMHC, to see a family physician for complaints of urinary frequency, blurred vision, thirst, and weight loss. An on-site fingerstick revealed his blood glucose to be 357 mg/dL. Given the presumptive diagnosis of diabetes, we checked his bloodwork, prescribed metformin, and referred him for diabetes education. That evening, his lab results showed a hemoglobin A1C > 17%, a basic metabolic panel with an anion gap, ketones in the urine, and a low C-peptide level. We were unable to reach Mr. C by phone for further management.

● How would you proceed with this patient?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Coordination of behavioral health and primary care can take many forms, from simple synchronized care via referral, to co-located services, to fully integrated care.1 Reverse integration, the subject of this article, is the provision of primary care in mental health or substance use disorder treatment settings. Published evidence to date regarding this model is minimal. This article describes our experience in developing a model of reverse integration in which family physicians and nurse practitioners are embedded in a CMHC with psychiatric providers, counselors, and social workers to jointly address physical and behavioral health care issues and address social determinants of health.

The rationale for reverse integration

Many individuals with serious mental illness (SMI), including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, have rates of comorbid chronic physical health conditions that are higher than in the general population. These conditions include obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis.2 Outcomes in the SMI group are also considerably worse than in the general population. People with SMI have a demonstrated loss of up to 32 years of potential life per patient compared with the general-population average, primarily due to poor physical health.2 Maladaptive health behaviors such as poor diet, lack of physical activity, tobacco use, and substance use contribute to this increased mortality.2,3 Social determinants of poor health are more prevalent among individuals with SMI, and a relative inability to collaborate in one’s own health care due to psychiatric symptoms further exacerbates the challenges.

Many individuals with SMI receive psychiatric care, case management, counseling, and psychosocial services in CMHCs. Their psychiatric caregiver may be their only regular health care provider. Family physicians—who receive residency training in behavioral health and social determinants of health in community settings—are distinctively capable of improving overall health care outcomes of patients with SMI.

THE ADVANTAGES OF A REVERSE-INTEGRATION PRACTICE MODEL

Delivering primary care in a CMHC with a behavioral health team can benefit patients with SMI and be a satisfying practice for family physicians. Specifically, family physicians

- find that caring for complex patients can be less stressful because they benefit from the knowledge and resources of the CMHC team. The CMHC team offers case management, counseling, employment services, and housing assistance, so the primary care provider and patient are well supported.

- see fewer patients per hour due to higher visit complexity (and coding). In our experience, team-based care and additional time with patients make complex patient care more enjoyable and less frustrating.

- benefit from a situation in which patients feel safe because the CMHC support staff knows them well.

Continue to: Other benefits

Other benefits. When primary care is delivered in a CMHC, there are “huddles” and warm handoffs that allow for bidirectional collaboration and care coordination between the primary care and behavioral health teams in real time. In addition, family medicine residents, medical students, and other learners can be successfully included in an IBH clinic for patients with SMI. The behavioral health team provides the mentorship, education, and modelling of skills needed to work with this population, including limit-setting, empathy, patience, and motivational interviewing.

For their part, learners self-report increased comfort and interest in working with underserved populations and improved awareness of the social determinants of health after these experiences.4,5 Many patients at CMHCs are comfortable working with learners if continuity is maintained with a primary care provider.

Challenges we’ve faced, tips we can offer

For primary care providers, the unique workplace culture, terminology, and patient population encountered in a CMHC can be challenging. Also challenging can be the combining of things such as electronic medical records (EMRs).

Culture. The CMHC model focuses on team-based care spearheaded by case managers, in contrast to the traditional family medicine model wherein the physician coordinates services. Case managers provide assessments of client stability and readiness to be seen. They also attend primary care visits to support patient interactions, provide important psychosocial information, and assess adherence to care.

Terminology. It’s not always easy to shift to different terminology in this culture. Thus, orientation needs to address things such as the use of the word “patient,” rather than “client,” when charting.

Continue to: The complexities of the patient population

The complexities of the patient population. Many patients treated at a CMHC have a history of trauma, anxiety, and paranoia, requiring adjustments to exam practices such as using smaller speculums, providing more physical space, and offering to leave examination room doors open while patients are waiting.

In addition, individuals with SMI often have multiple health conditions, but they may become uncomfortable with physical closeness, grow tired of conversation, or feel overwhelmed when asked to complete multiple tasks in 1 visit. As a result, visits may need to be shorter and more frequent.

It’s also worth noting that, in our experience, CMHC patients may have a higher no-show rate than typical primary care clinics, requiring flexibility in scheduling. To fill vacant primary care time slots, our front desk staff uses strategies such as waiting lists and offering walk-in visits to patients who are on site for other services.

Ideally, IBH clinics use a single, fully integrated EMR, but this is not always possible. If the primary care and CMHC EMR systems do not connect, then record review and repeat documentation is needed, while care is taken to adhere to the confidentiality standards of a particular state.

Standards of care and state policies. Written standards of care, procedures, and accreditation in CMHCs rarely include provisions for common primary care practice, such as vaccines, in-clinic medications, and implements for simple procedures. To provide these services in our clinic, we ordered/stocked the needed supplies and instituted protocols that mirrored our other outpatient family medicine clinical sites.

Continue to: Some states may have...

Some states may have policies that prevent reimbursement for mental health and primary care services billed on the same day. Seeing a family physician and a psychiatry provider on the same day is convenient for patients and allows for collaboration between providers. But reimbursement rules can vary by state, so starting an IBH clinic like this requires research into local billing regulations.

WANT TO START AN INTEGRATED BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CLINIC?

Detailed instruction on starting a primary care clinic in a CMHC is beyond the scope of this article. However, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration provides guidance on integrating primary care services into a local CMHC.6 Start by performing a baseline needs assessment of the CMHC and its patients to help guide clinic design. Leadership buy-in is key.

Leadership must provide adequate time and financial and technological support. This includes identifying appropriate space for primary care, offering training on using the EMR, and obtaining support from Finance to develop a realistic and competent business plan with an appropriate budgetary runway for start-up. (This may include securing grants in the beginning.)

We recommend starting small and expanding slowly. Once the clinic is operational, formal pathways for good communication are necessary. This includes holding regular team meetings to develop and revise clinic workflows—eg, patient enrollment, protocols, and administrative procedures such as managing medications and vaccinations—as well as addressing space, staffing, and training issues that arise. The IBH transitional leadership structure must include clinicians from both primary care and behavioral health, support staff, and the administration. Finally, you need the right staff—people who are passionate, flexible, and interested in trying something new.

THE CASE

The next day, an outreach was made to the CMHC nurse, who had the case manager go to Mr. C’s house and bring him to the CMHC for education on insulin injection, glucometer use, and diabetes nutrition. Mr. C was prescribed long-acting insulin at bedtime; his metformin was stopped and he was monitored closely.

Continue to: Mr. C now calls...

Mr. C now calls the CMHC nurse every few weeks to report his blood sugar levels, have his insulin dose adjusted, or just say “hello.” He continues to see his psychiatrist every month and his family physician every 4 months. The team collaborates as issues arise. His diabetes has been well controlled for more than 3 years.

The IBH clinic has grown in number of patients and family medicine providers, is self-sustaining, and has expanded services to include hepatitis C treatment.

1. Rajesh R, Tampi R, Balachandran S. The case for behavioral health integration into primary care. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:278-284.

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. 2006. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Mortality%20and%20Morbidity%20Final%20Report%208.18.08_0.pdf

3. Dickerson F, Stallings, CR, Origoni AE, et al. Cigarette Smoking among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in routine clinical settings, 1999-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:44-50.

4. Raddock M, Antenucci C, Chrisman L. Innovative primary care training: caring for the urban underserved. Innovations in Education Poster Session, Case School of Medicine Annual Education Retreat, Cleveland, OH, March 3, 2016.

5. Berg K, Antenucci C, Raddock M, et al. Deciding to care: medical students and patients’ social circumstances. Poster: Annual meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making. Pittsburgh, PA. October 2017.

6. Heath B, Wise Romero P, and Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. Washington, D.C. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. March 2013. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.pcpcc.org/resource/standard-framework-levels-integrated-healthcare

1. Rajesh R, Tampi R, Balachandran S. The case for behavioral health integration into primary care. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:278-284.

2. Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, et al. Morbidity and Mortality in People with Serious Mental Illness. 2006. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Mortality%20and%20Morbidity%20Final%20Report%208.18.08_0.pdf

3. Dickerson F, Stallings, CR, Origoni AE, et al. Cigarette Smoking among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in routine clinical settings, 1999-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:44-50.

4. Raddock M, Antenucci C, Chrisman L. Innovative primary care training: caring for the urban underserved. Innovations in Education Poster Session, Case School of Medicine Annual Education Retreat, Cleveland, OH, March 3, 2016.

5. Berg K, Antenucci C, Raddock M, et al. Deciding to care: medical students and patients’ social circumstances. Poster: Annual meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making. Pittsburgh, PA. October 2017.

6. Heath B, Wise Romero P, and Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare. Washington, D.C. SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. March 2013. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.pcpcc.org/resource/standard-framework-levels-integrated-healthcare

Helping your obese patient achieve a healthier weight

In 2015-2016, almost 40% of adults and 18.5% of children ages 2 to 19 years in the United States met the definition for obesity—a chronic, relapsing, multifactorial, neurobehavioral disease that results in adverse metabolic, biomechanical, and psychosocial health consequences.1,2

Tremendous resources have been invested in research, policy development, and public education to try to prevent obesity and its related complications. Despite this, the obesity epidemic has worsened. Here, we explore how to evaluate and treat obese patients in a primary care setting based on the evidence and our experience seeing patients specifically for weight management in a family medicine residency teaching clinic. Pharmacotherapy and surgery, while often helpful, are outside the scope of this article.

It begins withan obesity-friendly office

Patients may have reservations about health care interactions specific to obesity, so it is important to invite them into a setting that facilitates trust and encourages collaboration. Actively engage patients with unhealthy weight by creating an environment where they feel comfortable. Offer wide chairs without armrests, which will easily accommodate patients of all sizes, and ensure that scales have a weight capacity > 400 lb. Communicate a message to patients, via waiting room materials and videos, that focuses on health rather than on weight or body mass index (BMI).

Understand the patient’s goals and challenges

Most (although not all) family physicians will see obese patients in the context of a visit for diabetes, hypertension, or another condition. However, we feel that having visits specifically to address weight in the initial stages of weight management is helpful. The focus of an initial visit should be getting to know how obesity has affected the patient and what his or her motive is in attempting to lose weight. Explore previous attempts at weight loss and establish what the patient’s highest weight has been, as this will impact weight-loss goals. For example, if a patient has weighed > 300 lb all her adult life, it will be extremely difficult to maintain a weight loss of 150 lb.

What else to ask about. Discuss stressors that may be causing increased food intake or poor food choices, including hunger, anger, loneliness, and sleep difficulties. Multidisciplinary care including a psychologist can aid in addressing these issues. Ask patients if they keep a food diary (and if not, recommend that they start), as food diaries are often helpful in elucidating eating and drinking patterns. Determine a patient’s current and past levels of physical activity, as this will guide the fitness goals you develop for him or her.

Screen for psychosocial disorders

As noted earlier, the physical component of obesity is commonly associated with mood disorders such as anxiety and depression.2 This requires a multidisciplinary team effort to facilitate healing in the patient struggling with obesity.

Screening for depression and anxiety using standardized tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 is encouraged in patients who are overweight or obese. Positive screens should be addressed as part of the patient’s treatment plan, as untreated depression and anxiety can inhibit success with weight loss. Be mindful that many medications commonly used to treat these conditions can impair weight loss and even promote weight gain.

Continue to: Don't overlook binge-eating disorders

Don’t overlook binge-eating disorders. Screening specifically for binge-eating disorders is important, given the implications on treatment. The US Department of Veterans Affairs developed a single-item tool for this purpose, the VA Binge Eating Screener. The validated questionnaire asks, “On average, how often have you eaten extremely large amounts of food at one time and felt that your eating was out of control at that time?” Response options are: “Never,” “< 1 time/week,” “1 time/week,” “2-4 times/week,” and “5+ times/week.” A response of ≥ 2 times/week had a sensitivity of 88.9% and specificity of 83.2% for binge-eating disorder.3

Patients with positive screens should undergo psychotherapy and consider pharmacotherapy with lisdexamfetamine as part of their treatment plan. Caution should be used if recommending intermittent fasting for someone with binge-eating disorder.

Evaluate for underlying causes and assess for comorbidities

Review the patient’s current medication list and history. Many medications can cause weight gain, and weight loss can often be achieved by deprescribing such medications. When feasible, prescribe an alternative medication with a more favorable weight profile. A previous article in The Journal of Family Practice addresses this in more depth.4

Laboratory and other testing

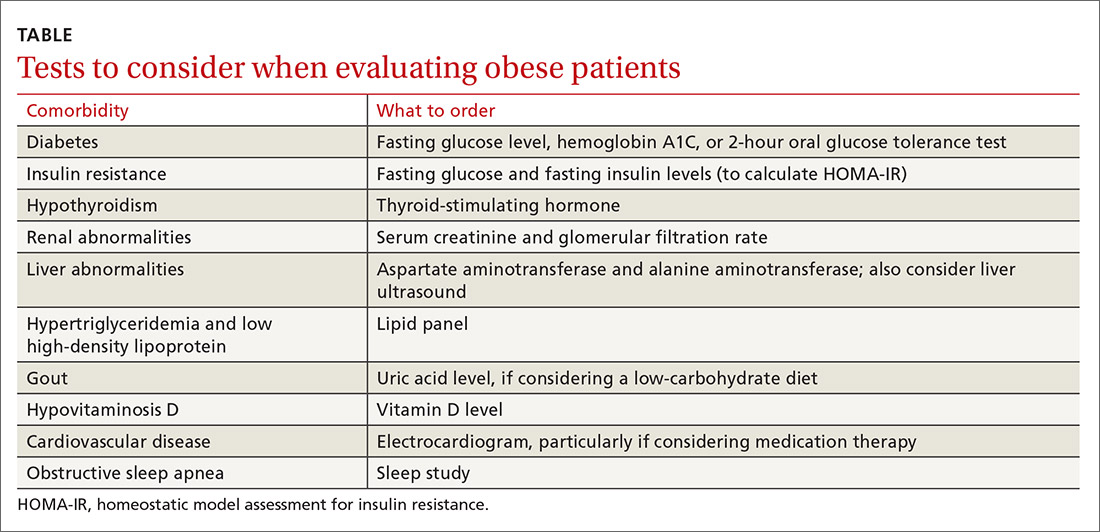

Laboratory analysis should primarily be focused on determining treatment alterations specific to underlying pathophysiology. Tests to consider ordering are outlined in the Table

Diabetes and insulin resistance. The American Diabetes Association recommends screening patients who are overweight or obese and have an additional risk factor for diabetes.5 This can be done by obtaining a fasting glucose level, hemoglobin A1C, or a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test.

Continue to: Since it is known that...

Since it is known that insulin resistance increases the risk for coronary heart disease6 and can be treated effectively,7 we recommend testing for insulin resistance in patients who do not already have impaired fasting glucose, prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, or impaired glucose tolerance. The homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)8 is a measure of insulin resistance and can be calculated from the fasting insulin and fasting glucose levels. This measure should not be done in isolation, but it can be a useful adjunct in identifying patients with insulin resistance and directing treatment.

If there is evidence of diabetes or insulin resistance, consider treatment with metformin ± initiation of a low-carbohydrate diet.

Hypothyroidism. Consider screening for thyroid dysfunction with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level, if it has not been checked previously.

Renal abnormalities. When serum creatinine levels and glomerular filtration rate indicate chronic kidney disease, consider recommending a protein-restricted diet and adjust medications according to renal dosing protocols, as indicated.

Liver abnormalities, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Monitor aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase for resolution of elevations as weight loss is achieved. If abnormalities persist, consider ordering a liver ultrasound. Traditionally, low-calorie diets have been prescribed to treat NAFLD, but evidence shows that low-carbohydrate diets can also be effective.9

Continue to: Hypertriglyceridemia and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels

Hypertriglyceridemia and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels. Obtain a lipid panel if one has not been completed within the past several years, as hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL can improve dramatically with specific dietary changes.7 Observe trends to assess for resolution of lipid abnormalities as weight loss is achieved.

Gout. Consider checking a uric acid level if you are thinking about recommending a low-carbohydrate diet, particularly in patients with a history of gout, as this may temporarily increase the risk of gout flare.

Hypovitaminosis D. If the patient’s vitamin D level is low, consider appropriate supplementation to support the patient’s overall health. While vitamin D deficiency is common in obesity, the role of supplementation in this population is unclear.

Cardiovascular disease. Consider ordering an electrocardiogram, particularly if you are thinking of prescribing medication therapy. Use caution with initiation of certain medications, such as phentermine or diethylproprion, in the presence of arrhythmias or active cardiovascular disease.

Obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep health is important to address, since obesity is one of the most significant risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea.10 If your patient is given a diagnosis of OSA following a sleep study, consider treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), although there are conflicting studies regarding the effects of CPAP therapy in OSA on weight.11,12

Continue to: Provide guidance on lifestyle changes

Provide guidance on lifestyle changes

Addressing obesity with patients can be challenging in a busy primary care clinic, but it is imperative to helping patients achieve overall health. Counseling on nutrition and physical activity is an important part of this process.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to nutrition counseling. Focus on creating individualized plans through which patients can achieve success. Some guidance follows, but also beware of common pitfalls that we have observed in clinical practice which, when addressed, can enable significant weight loss (see “Common pitfalls inhibiting weight loss”).

SIDEBAR

Common pitfalls inhibiting weight loss

On the part of the patient:

- Continuing to consume substantial amounts of high-calorie drinks.

- Taking in excessive amounts of sugar-rich foods, including cough drops.

- Using non-nutritive sweeteners (eg, aspartame, saccharin, sucralose, and erythritol). Although the mechanism is not certain, some people are able to lose weight while consuming these substances, while others are not.

On the part of the provider:

- Prescribing a diet that the patient cannot sustain long term.

- Overlooking the issue of food availability for the patient.

Choose an approach that works for the patient. Commonly prescribed diets to address obesity include, but are not limited to, Atkins, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), Glycemic Index, Mediterranean, Ornish, Paleolithic, Zone, whole food plant-based, and ketogenic. We attempt to engage patients in making the decision on what food choices are appropriate for them considering their food availability, culture, and belief systems. For patients who prefer a vegan or vegetarian whole food diet, it is important to note that these diets are generally deficient in vitamin B12 and omega 3 fatty acids, so supplementing these should be considered.

Rather than focus on a specific diet, which may not be sustainable long term, encourage healthy eating habits. Low-carbohydrate diets have been shown to promote greater weight loss compared to low-fat diets.13,14 Low-calorie diets can also be quite effective in promoting short-term weight loss. In our clinic, when weight loss is the primary goal, patients are typically encouraged to focus on either calorie or carbohydrate restriction in the initial stages of weight loss.

Eliminate sugar and refined carbohydrates. While rigorous mortality data are not available, more recent trials have demonstrated significant improvements in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk markers, including weight reduction and diabetes reversal, when following a diet that markedly decreases carbohydrate intake, especially sugar and refined carbohydrates.7,14-17

Continue to: We recommend that patients focus...

We recommend that patients focus on eliminating sweetened beverages, such as soft drinks, sports drinks, energy drinks, vitamin water, sweet tea, chocolate milk, and Frappuccinos. We also recommend substantially limiting or eliminating fruit juices and fruit smoothies due to their high sugar content. For example, 8 oz of orange juice contains 26 g of carbohydrates, which is almost as much as 8 oz of soda.