User login

New COVID-19 Vaccines That Target KP.2 Variant Available

New COVID-19 vaccines formulated for better protection against the currently circulating variants have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

The COVID vaccines available this fall have been updated to better match the currently circulating COVID strains, said William Schaffner, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, in an interview.

“The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines — both mRNA vaccines — target the KP.2 variant, while the Novavax vaccine targets the JN.1 variant, which is a predecessor to KP.2,” said Dr. Schaffner, who also serves as a spokesperson for the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “The Novavax vaccine is a protein adjuvant vaccine made in a more traditional fashion and may appeal to those who remain hesitant about receiving an mRNA vaccine,” he explained. However, , he said.

Who Needs It?

“The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) continues to recommend that everyone in the United States who is age 6 months and older receive the updated COVID vaccine this fall, along with influenza vaccine,” Dr. Schaffner said.

“This was not a surprise because COVID will produce a sizable winter outbreak,” he predicted. Although older people and those who have chronic medical conditions such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or other immunocompromising conditions suffer the most serious impact of COVID, he said. “The virus can strike anyone, even the young and healthy.” The risk for long COVID persists as well, he pointed out.

The ACIP recommendation is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and other professional organizations, Dr. Shaffner said.

A frequently asked question is whether the COVID and flu vaccines can be given at the same time, and the answer is yes, according to a statement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“The optimal time to be vaccinated is late September and anytime during October in order to get the benefit of protection through the winter,” Dr. Schaffner said.

As with earlier versions of the COVID-19 vaccine, side effects vary from person to person. Reported side effects of the updated vaccine are similar to those seen with earlier versions and may include injection site pain, redness and swelling, fatigue, headache, muscle pain, chills, nausea, and fever, but most of these are short-lived, according to the CDC.

Clinical Guidance

The CDC’s clinical guidance for COVID-19 vaccination outlines more specific guidance for vaccination based on age, vaccination history, and immunocompromised status and will be updated as needed.

A notable difference in the latest guidance is the recommendation of only one shot for adults aged 65 years and older who are NOT moderately or severely immunocompromised. For those who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, the CDC recommends two to three doses of the same brand of vaccine.

Dr. Schaffner strongly encouraged clinicians to recommend the COVID-19 vaccination for all eligible patients. “COVID is a nasty virus that can cause serious disease in anyone,” and protection from previous vaccination or prior infection has likely waned, he said.

Dr. Schaffner also encouraged healthcare professionals and their families to lead by example. “We should all be vaccinated and let our patients know that we are vaccinated and that we want all our patents to be protected,” he said.

The updated COVID-19 vaccination recommendations have become much simpler for clinicians and patients, with a single messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine required for anyone older than 5 years, said David J. Cennimo, MD, associate professor of medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Disease at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey, in an interview.

“The recommendations are a bit more complex for children under 5 years old receiving their first vaccination; they require two to three doses depending on the brand,” he said. “It is important to review the latest recommendations to plan the doses with the correct interval timing. Considering the doses may be 3-4 weeks apart, start early,” he advised.

One-Time Dosing

Although the updated mRNA vaccine is currently recommended as a one-time dose, Dr. Cennimo said he can envision a scenario later in the season when a second dose is recommended for the elderly and those at high risk for severe illness. Dr. Cennimo said that he strongly agrees with the recommendations that everyone aged 6 months and older receive an updated COVID-19 vaccine. Older age remains the prime risk factor, but anyone can become infected, he said.

Predicting a prime time to get vaccinated is tricky because no one knows when the expected rise in winter cases will occur, said Dr. Cennimo.

“We know from years of flu vaccine data that some number of people who delay the vaccine will never return and will miss protection,” he said. Therefore, delaying vaccination is not recommended. Dr. Cennimo plans to follow his habit of getting vaccinated in early October. “I anticipate the maximal effectiveness of the vaccine will carry me through the winter,” he said.

Data support the safety and effectiveness for both flu and COVID vaccines if they are given together, and some research on earlier versions of COVID vaccines suggested that receiving flu and COVID vaccines together might increase the antibody response against COVID, but similar studies of the updated version have not been done, Dr. Cennimo said.

Clinicians may have to overcome the barrier of COVID fatigue to encourage vaccination, Dr. Cennimo said. Many people say they “want it to be over,” he said, but SARS-CoV-2, established as a viral respiratory infection, shows no signs of disappearing. In addition, new data continue to show higher mortality associated with COVID-19 than with influenza, he said.

“We need to explain to our patients that COVID-19 is still here and is still dangerous. The yearly influenza vaccination campaigns should have established and normalized the idea of an updated vaccine targeted for the season’s predicated strains is expected,” he emphasized. “We now have years of safety data behind these vaccines, and we need to make a strong recommendation for this protection,” he said.

COVID-19 vaccines are covered by private insurance, as well as by Medicare and Medicaid, according to the CDC. Vaccination for uninsured children is covered through the Vaccines for Children Program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New COVID-19 vaccines formulated for better protection against the currently circulating variants have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

The COVID vaccines available this fall have been updated to better match the currently circulating COVID strains, said William Schaffner, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, in an interview.

“The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines — both mRNA vaccines — target the KP.2 variant, while the Novavax vaccine targets the JN.1 variant, which is a predecessor to KP.2,” said Dr. Schaffner, who also serves as a spokesperson for the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “The Novavax vaccine is a protein adjuvant vaccine made in a more traditional fashion and may appeal to those who remain hesitant about receiving an mRNA vaccine,” he explained. However, , he said.

Who Needs It?

“The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) continues to recommend that everyone in the United States who is age 6 months and older receive the updated COVID vaccine this fall, along with influenza vaccine,” Dr. Schaffner said.

“This was not a surprise because COVID will produce a sizable winter outbreak,” he predicted. Although older people and those who have chronic medical conditions such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or other immunocompromising conditions suffer the most serious impact of COVID, he said. “The virus can strike anyone, even the young and healthy.” The risk for long COVID persists as well, he pointed out.

The ACIP recommendation is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and other professional organizations, Dr. Shaffner said.

A frequently asked question is whether the COVID and flu vaccines can be given at the same time, and the answer is yes, according to a statement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“The optimal time to be vaccinated is late September and anytime during October in order to get the benefit of protection through the winter,” Dr. Schaffner said.

As with earlier versions of the COVID-19 vaccine, side effects vary from person to person. Reported side effects of the updated vaccine are similar to those seen with earlier versions and may include injection site pain, redness and swelling, fatigue, headache, muscle pain, chills, nausea, and fever, but most of these are short-lived, according to the CDC.

Clinical Guidance

The CDC’s clinical guidance for COVID-19 vaccination outlines more specific guidance for vaccination based on age, vaccination history, and immunocompromised status and will be updated as needed.

A notable difference in the latest guidance is the recommendation of only one shot for adults aged 65 years and older who are NOT moderately or severely immunocompromised. For those who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, the CDC recommends two to three doses of the same brand of vaccine.

Dr. Schaffner strongly encouraged clinicians to recommend the COVID-19 vaccination for all eligible patients. “COVID is a nasty virus that can cause serious disease in anyone,” and protection from previous vaccination or prior infection has likely waned, he said.

Dr. Schaffner also encouraged healthcare professionals and their families to lead by example. “We should all be vaccinated and let our patients know that we are vaccinated and that we want all our patents to be protected,” he said.

The updated COVID-19 vaccination recommendations have become much simpler for clinicians and patients, with a single messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine required for anyone older than 5 years, said David J. Cennimo, MD, associate professor of medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Disease at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey, in an interview.

“The recommendations are a bit more complex for children under 5 years old receiving their first vaccination; they require two to three doses depending on the brand,” he said. “It is important to review the latest recommendations to plan the doses with the correct interval timing. Considering the doses may be 3-4 weeks apart, start early,” he advised.

One-Time Dosing

Although the updated mRNA vaccine is currently recommended as a one-time dose, Dr. Cennimo said he can envision a scenario later in the season when a second dose is recommended for the elderly and those at high risk for severe illness. Dr. Cennimo said that he strongly agrees with the recommendations that everyone aged 6 months and older receive an updated COVID-19 vaccine. Older age remains the prime risk factor, but anyone can become infected, he said.

Predicting a prime time to get vaccinated is tricky because no one knows when the expected rise in winter cases will occur, said Dr. Cennimo.

“We know from years of flu vaccine data that some number of people who delay the vaccine will never return and will miss protection,” he said. Therefore, delaying vaccination is not recommended. Dr. Cennimo plans to follow his habit of getting vaccinated in early October. “I anticipate the maximal effectiveness of the vaccine will carry me through the winter,” he said.

Data support the safety and effectiveness for both flu and COVID vaccines if they are given together, and some research on earlier versions of COVID vaccines suggested that receiving flu and COVID vaccines together might increase the antibody response against COVID, but similar studies of the updated version have not been done, Dr. Cennimo said.

Clinicians may have to overcome the barrier of COVID fatigue to encourage vaccination, Dr. Cennimo said. Many people say they “want it to be over,” he said, but SARS-CoV-2, established as a viral respiratory infection, shows no signs of disappearing. In addition, new data continue to show higher mortality associated with COVID-19 than with influenza, he said.

“We need to explain to our patients that COVID-19 is still here and is still dangerous. The yearly influenza vaccination campaigns should have established and normalized the idea of an updated vaccine targeted for the season’s predicated strains is expected,” he emphasized. “We now have years of safety data behind these vaccines, and we need to make a strong recommendation for this protection,” he said.

COVID-19 vaccines are covered by private insurance, as well as by Medicare and Medicaid, according to the CDC. Vaccination for uninsured children is covered through the Vaccines for Children Program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New COVID-19 vaccines formulated for better protection against the currently circulating variants have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

The COVID vaccines available this fall have been updated to better match the currently circulating COVID strains, said William Schaffner, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, in an interview.

“The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines — both mRNA vaccines — target the KP.2 variant, while the Novavax vaccine targets the JN.1 variant, which is a predecessor to KP.2,” said Dr. Schaffner, who also serves as a spokesperson for the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “The Novavax vaccine is a protein adjuvant vaccine made in a more traditional fashion and may appeal to those who remain hesitant about receiving an mRNA vaccine,” he explained. However, , he said.

Who Needs It?

“The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) continues to recommend that everyone in the United States who is age 6 months and older receive the updated COVID vaccine this fall, along with influenza vaccine,” Dr. Schaffner said.

“This was not a surprise because COVID will produce a sizable winter outbreak,” he predicted. Although older people and those who have chronic medical conditions such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or other immunocompromising conditions suffer the most serious impact of COVID, he said. “The virus can strike anyone, even the young and healthy.” The risk for long COVID persists as well, he pointed out.

The ACIP recommendation is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and other professional organizations, Dr. Shaffner said.

A frequently asked question is whether the COVID and flu vaccines can be given at the same time, and the answer is yes, according to a statement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“The optimal time to be vaccinated is late September and anytime during October in order to get the benefit of protection through the winter,” Dr. Schaffner said.

As with earlier versions of the COVID-19 vaccine, side effects vary from person to person. Reported side effects of the updated vaccine are similar to those seen with earlier versions and may include injection site pain, redness and swelling, fatigue, headache, muscle pain, chills, nausea, and fever, but most of these are short-lived, according to the CDC.

Clinical Guidance

The CDC’s clinical guidance for COVID-19 vaccination outlines more specific guidance for vaccination based on age, vaccination history, and immunocompromised status and will be updated as needed.

A notable difference in the latest guidance is the recommendation of only one shot for adults aged 65 years and older who are NOT moderately or severely immunocompromised. For those who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, the CDC recommends two to three doses of the same brand of vaccine.

Dr. Schaffner strongly encouraged clinicians to recommend the COVID-19 vaccination for all eligible patients. “COVID is a nasty virus that can cause serious disease in anyone,” and protection from previous vaccination or prior infection has likely waned, he said.

Dr. Schaffner also encouraged healthcare professionals and their families to lead by example. “We should all be vaccinated and let our patients know that we are vaccinated and that we want all our patents to be protected,” he said.

The updated COVID-19 vaccination recommendations have become much simpler for clinicians and patients, with a single messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine required for anyone older than 5 years, said David J. Cennimo, MD, associate professor of medicine and pediatrics in the Division of Infectious Disease at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey, in an interview.

“The recommendations are a bit more complex for children under 5 years old receiving their first vaccination; they require two to three doses depending on the brand,” he said. “It is important to review the latest recommendations to plan the doses with the correct interval timing. Considering the doses may be 3-4 weeks apart, start early,” he advised.

One-Time Dosing

Although the updated mRNA vaccine is currently recommended as a one-time dose, Dr. Cennimo said he can envision a scenario later in the season when a second dose is recommended for the elderly and those at high risk for severe illness. Dr. Cennimo said that he strongly agrees with the recommendations that everyone aged 6 months and older receive an updated COVID-19 vaccine. Older age remains the prime risk factor, but anyone can become infected, he said.

Predicting a prime time to get vaccinated is tricky because no one knows when the expected rise in winter cases will occur, said Dr. Cennimo.

“We know from years of flu vaccine data that some number of people who delay the vaccine will never return and will miss protection,” he said. Therefore, delaying vaccination is not recommended. Dr. Cennimo plans to follow his habit of getting vaccinated in early October. “I anticipate the maximal effectiveness of the vaccine will carry me through the winter,” he said.

Data support the safety and effectiveness for both flu and COVID vaccines if they are given together, and some research on earlier versions of COVID vaccines suggested that receiving flu and COVID vaccines together might increase the antibody response against COVID, but similar studies of the updated version have not been done, Dr. Cennimo said.

Clinicians may have to overcome the barrier of COVID fatigue to encourage vaccination, Dr. Cennimo said. Many people say they “want it to be over,” he said, but SARS-CoV-2, established as a viral respiratory infection, shows no signs of disappearing. In addition, new data continue to show higher mortality associated with COVID-19 than with influenza, he said.

“We need to explain to our patients that COVID-19 is still here and is still dangerous. The yearly influenza vaccination campaigns should have established and normalized the idea of an updated vaccine targeted for the season’s predicated strains is expected,” he emphasized. “We now have years of safety data behind these vaccines, and we need to make a strong recommendation for this protection,” he said.

COVID-19 vaccines are covered by private insurance, as well as by Medicare and Medicaid, according to the CDC. Vaccination for uninsured children is covered through the Vaccines for Children Program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated COVID Vaccines: Who Should Get One, and When?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two updated mRNA COVID vaccines, one by Moderna and the other by Pfizer, have been authorized or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for those aged 6 months or older.

Both vaccines target Omicron’s KP.2 strain of the JN.1 lineage. An updated protein-based version by Novavax, also directed at JN.1, has been authorized, but only for those aged 12 years or older.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends a dose of the 2024-2025 updated COVID vaccine for everyone aged 6 months or older. This includes people who have never been vaccinated against COVID, those who have been vaccinated, as well as people with previous COVID infection.

The big question is when, and FDA and CDC have set some parameters. For mRNA updated vaccines, patients should wait at least 2 months after their last dose of any COVID vaccine before getting a dose of the updated vaccine.

If the patient has recently had COVID, the wait time is even longer: Patients can wait 3 months after a COVID infection to be vaccinated, but they don’t have to. FDA’s instructions for the Novavax version are not as straightforward. People can get an updated Novavax dose at least 2 months after their last mRNA COVID vaccine dose, or at least 2 months after completing a Novavax two-dose primary series. Those two Novavax doses should be given at least 3 weeks apart.

Patients can personalize their vaccine plan. They will have the greatest protection in the first few weeks to months after a vaccine, after which antibodies tend to wane. It is a good idea to time vaccination so that protection peaks at big events like weddings and major meetings.

If patients decide to wait, they run the risk of getting a COVID infection. Also keep in mind which variants are circulating and the amount of local activity. Right now, there is a lot of COVID going around, and most of it is related to JN.1, the target of this year’s updated vaccine. If patients decide to wait, they should avoid crowded indoor settings or wear a high-quality mask for some protection.

Here’s the bottom line: Most people (more than 95%) have some degree of COVID protection from previous infection, vaccination, or both. But if they haven’t recently had COVID infection and didn’t get a dose of last year’s vaccine, they are sitting ducks for getting sick without updated protection. The best way to stay well is to get a dose of the updated vaccine as soon as possible. This is especially true for those in high-risk groups or who are near someone who is high risk.

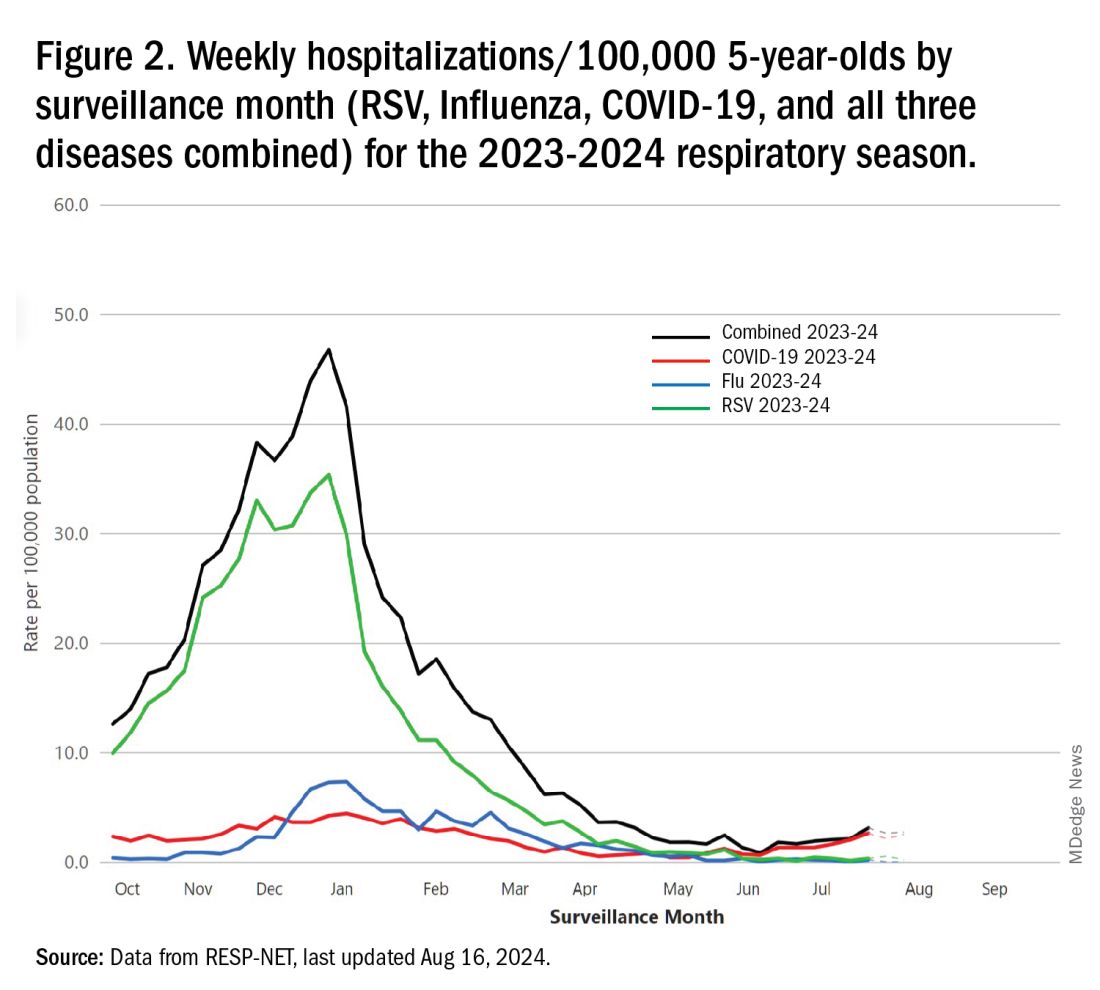

Two thirds of COVID hospitalizations are in those aged 65 or older. Hospitalization rates are highest for those aged 75 or older and among infants under 6 months of age. These babies are too young to be vaccinated, but maternal vaccination during pregnancy and breastfeeding can help protect them.

We’re still seeing racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-related hospitalizations, which are highest among American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Black populations. People with immunocompromising conditions, those with chronic medical conditions, and people living in long-term care facilities are also at greater risk. Unlike last year, additional mRNA doses are not recommended for those aged 65 or older at this time, but that could change.

Since 2020, we’ve come a long way in our fight against COVID, but the battle is still on. In 2023, nearly a million people were hospitalized from COVID. More than 75,000 died. COVID vaccines help protect us from severe disease, hospitalization, and death.

Let’s face it — we all have booster fatigue, but COVID is now endemic. It’s here to stay, and it’s much safer to update antibody protection with vaccination than with infection. Another benefit of getting vaccinated is that it decreases the chance of getting long COVID. The uptake of last year’s COVID vaccine was abysmal; only about 23% of adults and 14% of children received it.

But this is a new year and a new vaccine. Please make sure your patients understand that the virus has changed a lot. Antibodies we built from previous infection and previous vaccination don’t work as well against these new variants. Antibody levels wane over time, so even if they missed the last few vaccine doses without getting sick, they really should consider getting a dose of this new vaccine. The 2024-2025 updated COVID vaccine is the best way to catch up, update their immunity, and keep them protected.

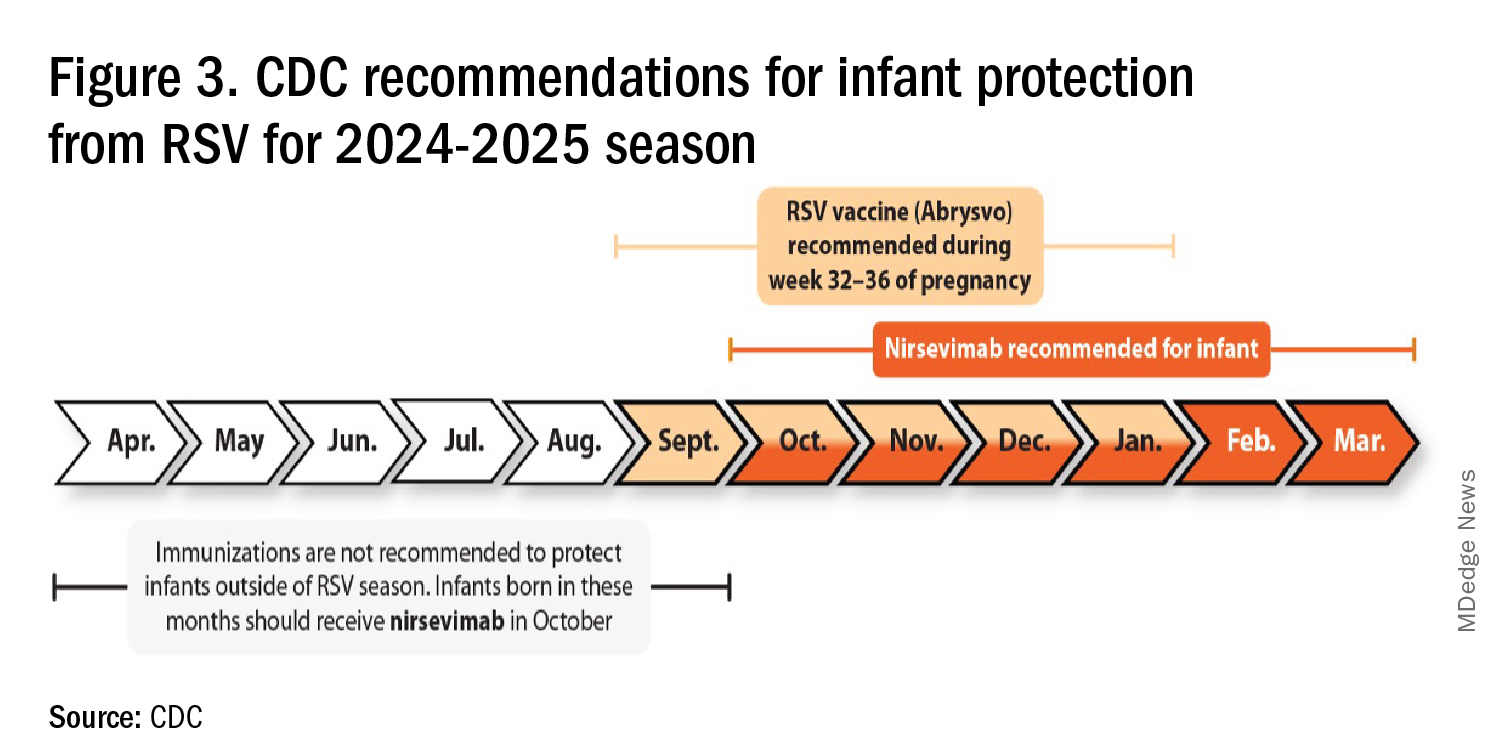

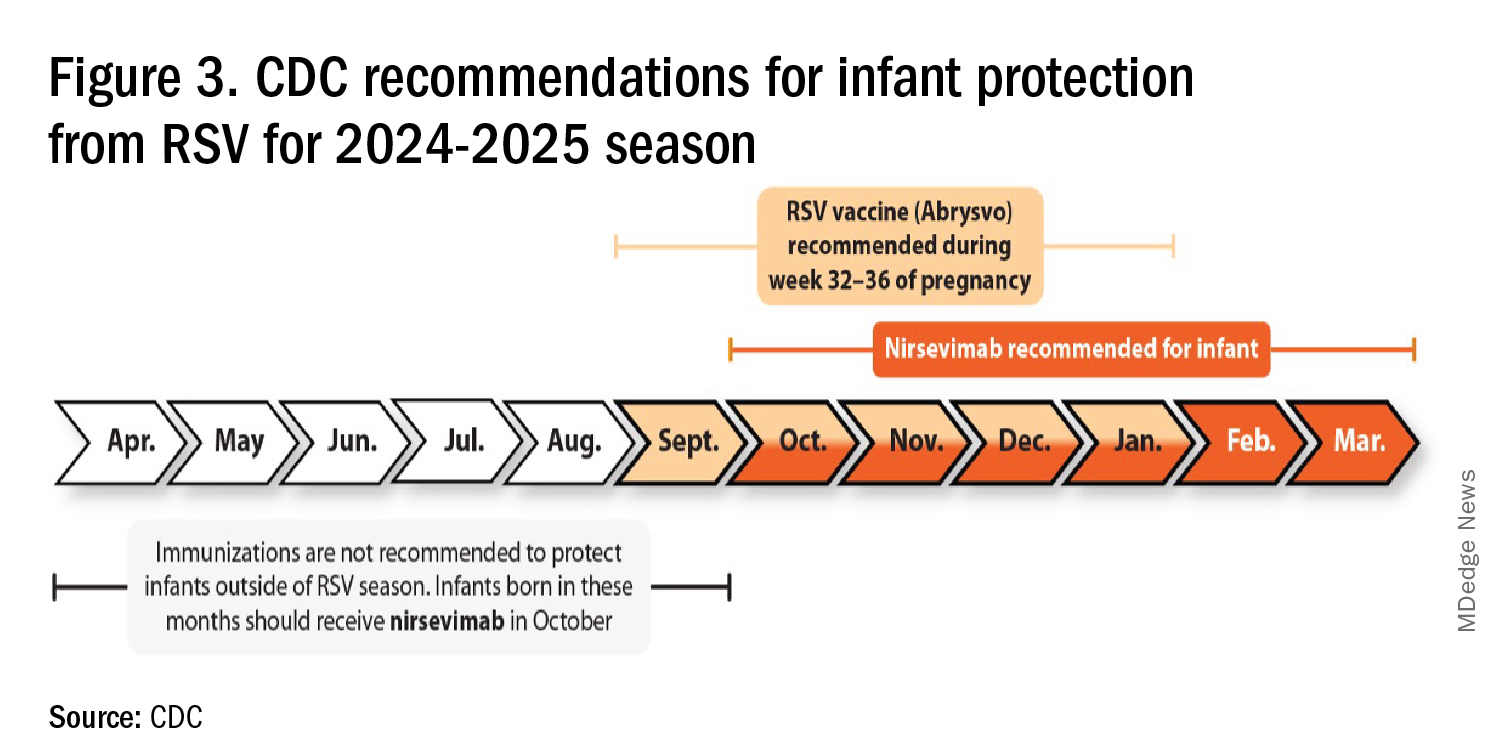

Furthermore, we are now entering respiratory virus season, which means we need to think about, recommend, and administer three shots if indicated: COVID, flu, and RSV. Now is the time. Patients can get all three at the same time, in the same visit, if they choose to do so.

Your recommendation as a physician is powerful. Adults and children who receive a healthcare provider recommendation are more likely to get vaccinated.

Dr. Fryhofer is an adjunct clinical associate professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. She reported conflicts of interest with the American Medical Association, the Medical Association of Atlanta, the American College of Physicians, and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two updated mRNA COVID vaccines, one by Moderna and the other by Pfizer, have been authorized or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for those aged 6 months or older.

Both vaccines target Omicron’s KP.2 strain of the JN.1 lineage. An updated protein-based version by Novavax, also directed at JN.1, has been authorized, but only for those aged 12 years or older.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends a dose of the 2024-2025 updated COVID vaccine for everyone aged 6 months or older. This includes people who have never been vaccinated against COVID, those who have been vaccinated, as well as people with previous COVID infection.

The big question is when, and FDA and CDC have set some parameters. For mRNA updated vaccines, patients should wait at least 2 months after their last dose of any COVID vaccine before getting a dose of the updated vaccine.

If the patient has recently had COVID, the wait time is even longer: Patients can wait 3 months after a COVID infection to be vaccinated, but they don’t have to. FDA’s instructions for the Novavax version are not as straightforward. People can get an updated Novavax dose at least 2 months after their last mRNA COVID vaccine dose, or at least 2 months after completing a Novavax two-dose primary series. Those two Novavax doses should be given at least 3 weeks apart.

Patients can personalize their vaccine plan. They will have the greatest protection in the first few weeks to months after a vaccine, after which antibodies tend to wane. It is a good idea to time vaccination so that protection peaks at big events like weddings and major meetings.

If patients decide to wait, they run the risk of getting a COVID infection. Also keep in mind which variants are circulating and the amount of local activity. Right now, there is a lot of COVID going around, and most of it is related to JN.1, the target of this year’s updated vaccine. If patients decide to wait, they should avoid crowded indoor settings or wear a high-quality mask for some protection.

Here’s the bottom line: Most people (more than 95%) have some degree of COVID protection from previous infection, vaccination, or both. But if they haven’t recently had COVID infection and didn’t get a dose of last year’s vaccine, they are sitting ducks for getting sick without updated protection. The best way to stay well is to get a dose of the updated vaccine as soon as possible. This is especially true for those in high-risk groups or who are near someone who is high risk.

Two thirds of COVID hospitalizations are in those aged 65 or older. Hospitalization rates are highest for those aged 75 or older and among infants under 6 months of age. These babies are too young to be vaccinated, but maternal vaccination during pregnancy and breastfeeding can help protect them.

We’re still seeing racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-related hospitalizations, which are highest among American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Black populations. People with immunocompromising conditions, those with chronic medical conditions, and people living in long-term care facilities are also at greater risk. Unlike last year, additional mRNA doses are not recommended for those aged 65 or older at this time, but that could change.

Since 2020, we’ve come a long way in our fight against COVID, but the battle is still on. In 2023, nearly a million people were hospitalized from COVID. More than 75,000 died. COVID vaccines help protect us from severe disease, hospitalization, and death.

Let’s face it — we all have booster fatigue, but COVID is now endemic. It’s here to stay, and it’s much safer to update antibody protection with vaccination than with infection. Another benefit of getting vaccinated is that it decreases the chance of getting long COVID. The uptake of last year’s COVID vaccine was abysmal; only about 23% of adults and 14% of children received it.

But this is a new year and a new vaccine. Please make sure your patients understand that the virus has changed a lot. Antibodies we built from previous infection and previous vaccination don’t work as well against these new variants. Antibody levels wane over time, so even if they missed the last few vaccine doses without getting sick, they really should consider getting a dose of this new vaccine. The 2024-2025 updated COVID vaccine is the best way to catch up, update their immunity, and keep them protected.

Furthermore, we are now entering respiratory virus season, which means we need to think about, recommend, and administer three shots if indicated: COVID, flu, and RSV. Now is the time. Patients can get all three at the same time, in the same visit, if they choose to do so.

Your recommendation as a physician is powerful. Adults and children who receive a healthcare provider recommendation are more likely to get vaccinated.

Dr. Fryhofer is an adjunct clinical associate professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. She reported conflicts of interest with the American Medical Association, the Medical Association of Atlanta, the American College of Physicians, and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two updated mRNA COVID vaccines, one by Moderna and the other by Pfizer, have been authorized or approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for those aged 6 months or older.

Both vaccines target Omicron’s KP.2 strain of the JN.1 lineage. An updated protein-based version by Novavax, also directed at JN.1, has been authorized, but only for those aged 12 years or older.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends a dose of the 2024-2025 updated COVID vaccine for everyone aged 6 months or older. This includes people who have never been vaccinated against COVID, those who have been vaccinated, as well as people with previous COVID infection.

The big question is when, and FDA and CDC have set some parameters. For mRNA updated vaccines, patients should wait at least 2 months after their last dose of any COVID vaccine before getting a dose of the updated vaccine.

If the patient has recently had COVID, the wait time is even longer: Patients can wait 3 months after a COVID infection to be vaccinated, but they don’t have to. FDA’s instructions for the Novavax version are not as straightforward. People can get an updated Novavax dose at least 2 months after their last mRNA COVID vaccine dose, or at least 2 months after completing a Novavax two-dose primary series. Those two Novavax doses should be given at least 3 weeks apart.

Patients can personalize their vaccine plan. They will have the greatest protection in the first few weeks to months after a vaccine, after which antibodies tend to wane. It is a good idea to time vaccination so that protection peaks at big events like weddings and major meetings.

If patients decide to wait, they run the risk of getting a COVID infection. Also keep in mind which variants are circulating and the amount of local activity. Right now, there is a lot of COVID going around, and most of it is related to JN.1, the target of this year’s updated vaccine. If patients decide to wait, they should avoid crowded indoor settings or wear a high-quality mask for some protection.

Here’s the bottom line: Most people (more than 95%) have some degree of COVID protection from previous infection, vaccination, or both. But if they haven’t recently had COVID infection and didn’t get a dose of last year’s vaccine, they are sitting ducks for getting sick without updated protection. The best way to stay well is to get a dose of the updated vaccine as soon as possible. This is especially true for those in high-risk groups or who are near someone who is high risk.

Two thirds of COVID hospitalizations are in those aged 65 or older. Hospitalization rates are highest for those aged 75 or older and among infants under 6 months of age. These babies are too young to be vaccinated, but maternal vaccination during pregnancy and breastfeeding can help protect them.

We’re still seeing racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-related hospitalizations, which are highest among American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Black populations. People with immunocompromising conditions, those with chronic medical conditions, and people living in long-term care facilities are also at greater risk. Unlike last year, additional mRNA doses are not recommended for those aged 65 or older at this time, but that could change.

Since 2020, we’ve come a long way in our fight against COVID, but the battle is still on. In 2023, nearly a million people were hospitalized from COVID. More than 75,000 died. COVID vaccines help protect us from severe disease, hospitalization, and death.

Let’s face it — we all have booster fatigue, but COVID is now endemic. It’s here to stay, and it’s much safer to update antibody protection with vaccination than with infection. Another benefit of getting vaccinated is that it decreases the chance of getting long COVID. The uptake of last year’s COVID vaccine was abysmal; only about 23% of adults and 14% of children received it.

But this is a new year and a new vaccine. Please make sure your patients understand that the virus has changed a lot. Antibodies we built from previous infection and previous vaccination don’t work as well against these new variants. Antibody levels wane over time, so even if they missed the last few vaccine doses without getting sick, they really should consider getting a dose of this new vaccine. The 2024-2025 updated COVID vaccine is the best way to catch up, update their immunity, and keep them protected.

Furthermore, we are now entering respiratory virus season, which means we need to think about, recommend, and administer three shots if indicated: COVID, flu, and RSV. Now is the time. Patients can get all three at the same time, in the same visit, if they choose to do so.

Your recommendation as a physician is powerful. Adults and children who receive a healthcare provider recommendation are more likely to get vaccinated.

Dr. Fryhofer is an adjunct clinical associate professor of medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. She reported conflicts of interest with the American Medical Association, the Medical Association of Atlanta, the American College of Physicians, and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As Interest From Families Wanes, Pediatricians Scale Back on COVID Shots

When pediatrician Eric Ball, MD, opened a refrigerator full of childhood vaccines, all the expected shots were there — DTaP, polio, pneumococcal vaccine — except one.

“This is where we usually store our COVID vaccines, but we don’t have any right now because they all expired at the end of last year and we had to dispose of them,” said Dr. Ball, who is part of a pediatric practice in Orange County, California.

“We thought demand would be way higher than it was.”

Providers like Dr. Ball don’t want to waste money ordering doses that won’t be used, but they need enough on hand to vaccinate vulnerable children.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that anyone 6 months or older get the updated COVID vaccination, but in the 2023-24 vaccination season only about 15% of eligible children in the United States got a shot.

Dr. Ball said it was difficult to let vaccines go to waste in 2023. It was the first time the federal government was no longer picking up the tab for the shots, and providers had to pay upfront for the vaccines. Parents would often skip the COVID shot, which can have a very short shelf life, compared with other vaccines.

“Watching it sitting on our shelves expiring every 30 days, that’s like throwing away $150 repeatedly every day, multiple times a month,” Dr. Ball said.

in 2024, Dr. Ball slashed his fall vaccine order to the bare minimum to avoid another costly mistake.

“We took the number of flu vaccines that we order, and then we ordered 5% of that in COVID vaccines,” Dr. Ball said. “It’s a guess.”

That small vaccine order cost more than $63,000, he said.

Pharmacists, pharmacy interns, and techs are allowed to give COVID vaccines only to children age 3 and up, meaning babies and toddlers would need to visit a doctor’s office for inoculation.

It’s difficult to predict how parents will feel about the shots this fall, said Chicago pediatrician Scott Goldstein, MD. Unlike other vaccinations, COVID shots aren’t required for kids to attend school, and parental interest seems to wane with each new formulation. For a physician-owned practice such as Dr. Goldstein’s, the upfront cost of the vaccine can be a gamble.

“The cost of vaccines, that’s far and away our biggest expense. But it’s also the most important thing we do, you could argue, is vaccinating kids,” Dr. Goldstein said.

Insurance doesn’t necessarily cover vaccine storage accidents, which can put the practice at risk of financial ruin.

“We’ve had things happen like a refrigerator gets unplugged. And then we’re all of a sudden out $80,000 overnight,” Dr. Goldstein said.

South Carolina pediatrician Deborah Greenhouse, MD, said she would order more COVID vaccines for older children if the pharmaceutical companies that she buys from had a more forgiving return policy.

“Pfizer is creating that situation. If you’re only going to let us return 30%, we’re not going to buy much,” she said. “We can’t.”

Greenhouse owns her practice, so the remaining 70% of leftover shots would come out of her pocket.

Vaccine maker Pfizer will take back all unused COVID shots for young children, but only 30% of doses for people 12 and older.

Pfizer said in an Aug. 20 emailed statement, “The return policy was instituted as we recognize both the importance and the complexity of pediatric vaccination and wanted to ensure that pediatric offices did not have hurdles to providing vaccine to their young patients.”

Pfizer’s return policy is similar to policies from other drugmakers for pediatric flu vaccines, also recommended during the fall season. Physicians who are worried about unwanted COVID vaccines expiring on the shelves said flu shots cost them about $20 per dose, while COVID shots cost around $150 per dose.

“We run on a very thin margin. If we get stuck holding a ton of vaccine that we cannot return, we can’t absorb that kind of cost,” Dr. Greenhouse said.

Vaccine maker Moderna will accept COVID vaccine returns, but the amount depends on the individual contract with a provider. Novavax will accept the return of only unopened vaccines and doesn’t specify the amount they’ll accept.

Dr. Greenhouse wants to vaccinate as many children as possible but said she can’t afford to stock shots with a short shelf life. Once she runs out of the doses she’s ordered, Dr. Greenhouse plans to tell families to go to a pharmacy to get older children vaccinated. If pediatricians around the country are making the same calculations, doses for very small children could be harder to find at doctors’ offices.

“Frankly, it’s not an ideal situation, but it’s what we have to do to stay in business,” she said.

Dr. Ball worries that parents’ limited interest has caused pediatricians to minimize their vaccine orders, in turn making the newest COVID shots difficult to find once they become available.

“I think there’s just a misperception that it’s less of a big deal to get COVID, but I’m still sending babies to the hospital with COVID,” Dr. Ball said. “We’re still seeing kids with long COVID. This is with us forever.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

When pediatrician Eric Ball, MD, opened a refrigerator full of childhood vaccines, all the expected shots were there — DTaP, polio, pneumococcal vaccine — except one.

“This is where we usually store our COVID vaccines, but we don’t have any right now because they all expired at the end of last year and we had to dispose of them,” said Dr. Ball, who is part of a pediatric practice in Orange County, California.

“We thought demand would be way higher than it was.”

Providers like Dr. Ball don’t want to waste money ordering doses that won’t be used, but they need enough on hand to vaccinate vulnerable children.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that anyone 6 months or older get the updated COVID vaccination, but in the 2023-24 vaccination season only about 15% of eligible children in the United States got a shot.

Dr. Ball said it was difficult to let vaccines go to waste in 2023. It was the first time the federal government was no longer picking up the tab for the shots, and providers had to pay upfront for the vaccines. Parents would often skip the COVID shot, which can have a very short shelf life, compared with other vaccines.

“Watching it sitting on our shelves expiring every 30 days, that’s like throwing away $150 repeatedly every day, multiple times a month,” Dr. Ball said.

in 2024, Dr. Ball slashed his fall vaccine order to the bare minimum to avoid another costly mistake.

“We took the number of flu vaccines that we order, and then we ordered 5% of that in COVID vaccines,” Dr. Ball said. “It’s a guess.”

That small vaccine order cost more than $63,000, he said.

Pharmacists, pharmacy interns, and techs are allowed to give COVID vaccines only to children age 3 and up, meaning babies and toddlers would need to visit a doctor’s office for inoculation.

It’s difficult to predict how parents will feel about the shots this fall, said Chicago pediatrician Scott Goldstein, MD. Unlike other vaccinations, COVID shots aren’t required for kids to attend school, and parental interest seems to wane with each new formulation. For a physician-owned practice such as Dr. Goldstein’s, the upfront cost of the vaccine can be a gamble.

“The cost of vaccines, that’s far and away our biggest expense. But it’s also the most important thing we do, you could argue, is vaccinating kids,” Dr. Goldstein said.

Insurance doesn’t necessarily cover vaccine storage accidents, which can put the practice at risk of financial ruin.

“We’ve had things happen like a refrigerator gets unplugged. And then we’re all of a sudden out $80,000 overnight,” Dr. Goldstein said.

South Carolina pediatrician Deborah Greenhouse, MD, said she would order more COVID vaccines for older children if the pharmaceutical companies that she buys from had a more forgiving return policy.

“Pfizer is creating that situation. If you’re only going to let us return 30%, we’re not going to buy much,” she said. “We can’t.”

Greenhouse owns her practice, so the remaining 70% of leftover shots would come out of her pocket.

Vaccine maker Pfizer will take back all unused COVID shots for young children, but only 30% of doses for people 12 and older.

Pfizer said in an Aug. 20 emailed statement, “The return policy was instituted as we recognize both the importance and the complexity of pediatric vaccination and wanted to ensure that pediatric offices did not have hurdles to providing vaccine to their young patients.”

Pfizer’s return policy is similar to policies from other drugmakers for pediatric flu vaccines, also recommended during the fall season. Physicians who are worried about unwanted COVID vaccines expiring on the shelves said flu shots cost them about $20 per dose, while COVID shots cost around $150 per dose.

“We run on a very thin margin. If we get stuck holding a ton of vaccine that we cannot return, we can’t absorb that kind of cost,” Dr. Greenhouse said.

Vaccine maker Moderna will accept COVID vaccine returns, but the amount depends on the individual contract with a provider. Novavax will accept the return of only unopened vaccines and doesn’t specify the amount they’ll accept.

Dr. Greenhouse wants to vaccinate as many children as possible but said she can’t afford to stock shots with a short shelf life. Once she runs out of the doses she’s ordered, Dr. Greenhouse plans to tell families to go to a pharmacy to get older children vaccinated. If pediatricians around the country are making the same calculations, doses for very small children could be harder to find at doctors’ offices.

“Frankly, it’s not an ideal situation, but it’s what we have to do to stay in business,” she said.

Dr. Ball worries that parents’ limited interest has caused pediatricians to minimize their vaccine orders, in turn making the newest COVID shots difficult to find once they become available.

“I think there’s just a misperception that it’s less of a big deal to get COVID, but I’m still sending babies to the hospital with COVID,” Dr. Ball said. “We’re still seeing kids with long COVID. This is with us forever.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

When pediatrician Eric Ball, MD, opened a refrigerator full of childhood vaccines, all the expected shots were there — DTaP, polio, pneumococcal vaccine — except one.

“This is where we usually store our COVID vaccines, but we don’t have any right now because they all expired at the end of last year and we had to dispose of them,” said Dr. Ball, who is part of a pediatric practice in Orange County, California.

“We thought demand would be way higher than it was.”

Providers like Dr. Ball don’t want to waste money ordering doses that won’t be used, but they need enough on hand to vaccinate vulnerable children.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that anyone 6 months or older get the updated COVID vaccination, but in the 2023-24 vaccination season only about 15% of eligible children in the United States got a shot.

Dr. Ball said it was difficult to let vaccines go to waste in 2023. It was the first time the federal government was no longer picking up the tab for the shots, and providers had to pay upfront for the vaccines. Parents would often skip the COVID shot, which can have a very short shelf life, compared with other vaccines.

“Watching it sitting on our shelves expiring every 30 days, that’s like throwing away $150 repeatedly every day, multiple times a month,” Dr. Ball said.

in 2024, Dr. Ball slashed his fall vaccine order to the bare minimum to avoid another costly mistake.

“We took the number of flu vaccines that we order, and then we ordered 5% of that in COVID vaccines,” Dr. Ball said. “It’s a guess.”

That small vaccine order cost more than $63,000, he said.

Pharmacists, pharmacy interns, and techs are allowed to give COVID vaccines only to children age 3 and up, meaning babies and toddlers would need to visit a doctor’s office for inoculation.

It’s difficult to predict how parents will feel about the shots this fall, said Chicago pediatrician Scott Goldstein, MD. Unlike other vaccinations, COVID shots aren’t required for kids to attend school, and parental interest seems to wane with each new formulation. For a physician-owned practice such as Dr. Goldstein’s, the upfront cost of the vaccine can be a gamble.

“The cost of vaccines, that’s far and away our biggest expense. But it’s also the most important thing we do, you could argue, is vaccinating kids,” Dr. Goldstein said.

Insurance doesn’t necessarily cover vaccine storage accidents, which can put the practice at risk of financial ruin.

“We’ve had things happen like a refrigerator gets unplugged. And then we’re all of a sudden out $80,000 overnight,” Dr. Goldstein said.

South Carolina pediatrician Deborah Greenhouse, MD, said she would order more COVID vaccines for older children if the pharmaceutical companies that she buys from had a more forgiving return policy.

“Pfizer is creating that situation. If you’re only going to let us return 30%, we’re not going to buy much,” she said. “We can’t.”

Greenhouse owns her practice, so the remaining 70% of leftover shots would come out of her pocket.

Vaccine maker Pfizer will take back all unused COVID shots for young children, but only 30% of doses for people 12 and older.

Pfizer said in an Aug. 20 emailed statement, “The return policy was instituted as we recognize both the importance and the complexity of pediatric vaccination and wanted to ensure that pediatric offices did not have hurdles to providing vaccine to their young patients.”

Pfizer’s return policy is similar to policies from other drugmakers for pediatric flu vaccines, also recommended during the fall season. Physicians who are worried about unwanted COVID vaccines expiring on the shelves said flu shots cost them about $20 per dose, while COVID shots cost around $150 per dose.

“We run on a very thin margin. If we get stuck holding a ton of vaccine that we cannot return, we can’t absorb that kind of cost,” Dr. Greenhouse said.

Vaccine maker Moderna will accept COVID vaccine returns, but the amount depends on the individual contract with a provider. Novavax will accept the return of only unopened vaccines and doesn’t specify the amount they’ll accept.

Dr. Greenhouse wants to vaccinate as many children as possible but said she can’t afford to stock shots with a short shelf life. Once she runs out of the doses she’s ordered, Dr. Greenhouse plans to tell families to go to a pharmacy to get older children vaccinated. If pediatricians around the country are making the same calculations, doses for very small children could be harder to find at doctors’ offices.

“Frankly, it’s not an ideal situation, but it’s what we have to do to stay in business,” she said.

Dr. Ball worries that parents’ limited interest has caused pediatricians to minimize their vaccine orders, in turn making the newest COVID shots difficult to find once they become available.

“I think there’s just a misperception that it’s less of a big deal to get COVID, but I’m still sending babies to the hospital with COVID,” Dr. Ball said. “We’re still seeing kids with long COVID. This is with us forever.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Part of Taking a Good (Human) Patient History Includes Asking About Pet Vaccinations

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In my job, I spend 99% of my time thinking about ethical issues that arise in the care of human beings. That is the focus of our medical school, and that’s what we do.

However,

Recently, there has been a great increase in the number of pet owners who are saying, “I’m not going to vaccinate my pets.” As horrible as this sounds, what’s happening is vaccine hesitancy about vaccines used in humans is extending through some people to their pets.

The number of people who say they don’t trust things like rabies vaccine to be effective or safe for their pet animals is 40%, at least in surveys, and the American Veterinary Medical Association reports that 15%-18% of pet owners are not, in fact, vaccinating their pets against rabies.

Rabies, as I hope everybody knows, is one horrible disease. Even the treatment of it, should you get bitten by a rabid animal, is no fun, expensive, and hopefully something that can be administered quickly. It’s not always the case. Worldwide, at least 70,000 people die from rabies every year.

Obviously, there are many countries that are so terrified of rabies, they won’t let you bring pets in without quarantining them, say, England, for at least 6 months to a year, I believe, because they don’t want rabies getting into their country. They’re very strict about the movement of pets.

It is inexcusable for people, first, not to give their pets vaccines that prevent them getting distemper, parvovirus, or many other diseases that harm the pet. It’s also inexcusable to shorten your pet’s life or ask your patients to care for pets who get sick from many of these diseases that are vaccine preventable.

Worst of all, it’s inexcusable for any pet owner not to give a rabies vaccine to their pets. Were it up to me, I’d say you have to license your pet, and as part of that, you must mandate rabies vaccines for your dogs, cats, and other pets.

We know what happens when people encounter wild animals like raccoons and rabbits. It is not a good situation. Your pets can easily encounter a rabid animal and then put themselves in a position where they can harm their human owners.

We have an efficacious, safe treatment. If you’re dealing with someone, it might make sense to ask them, “Do you own a pet? Are you vaccinating?” It may not be something you’d ever thought about, but what we don’t need is rabies back in a bigger way in the United States than it’s been in the past.

I think, as a matter of prudence and public health, maybe firing up that question, “Got a pet in the house and are you vaccinating,” could be part of taking a good history.

Dr. Caplan is director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Center, New York City. He disclosed conflicts of interest with Johnson & Johnson and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In my job, I spend 99% of my time thinking about ethical issues that arise in the care of human beings. That is the focus of our medical school, and that’s what we do.

However,

Recently, there has been a great increase in the number of pet owners who are saying, “I’m not going to vaccinate my pets.” As horrible as this sounds, what’s happening is vaccine hesitancy about vaccines used in humans is extending through some people to their pets.

The number of people who say they don’t trust things like rabies vaccine to be effective or safe for their pet animals is 40%, at least in surveys, and the American Veterinary Medical Association reports that 15%-18% of pet owners are not, in fact, vaccinating their pets against rabies.

Rabies, as I hope everybody knows, is one horrible disease. Even the treatment of it, should you get bitten by a rabid animal, is no fun, expensive, and hopefully something that can be administered quickly. It’s not always the case. Worldwide, at least 70,000 people die from rabies every year.

Obviously, there are many countries that are so terrified of rabies, they won’t let you bring pets in without quarantining them, say, England, for at least 6 months to a year, I believe, because they don’t want rabies getting into their country. They’re very strict about the movement of pets.

It is inexcusable for people, first, not to give their pets vaccines that prevent them getting distemper, parvovirus, or many other diseases that harm the pet. It’s also inexcusable to shorten your pet’s life or ask your patients to care for pets who get sick from many of these diseases that are vaccine preventable.

Worst of all, it’s inexcusable for any pet owner not to give a rabies vaccine to their pets. Were it up to me, I’d say you have to license your pet, and as part of that, you must mandate rabies vaccines for your dogs, cats, and other pets.

We know what happens when people encounter wild animals like raccoons and rabbits. It is not a good situation. Your pets can easily encounter a rabid animal and then put themselves in a position where they can harm their human owners.

We have an efficacious, safe treatment. If you’re dealing with someone, it might make sense to ask them, “Do you own a pet? Are you vaccinating?” It may not be something you’d ever thought about, but what we don’t need is rabies back in a bigger way in the United States than it’s been in the past.

I think, as a matter of prudence and public health, maybe firing up that question, “Got a pet in the house and are you vaccinating,” could be part of taking a good history.

Dr. Caplan is director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Center, New York City. He disclosed conflicts of interest with Johnson & Johnson and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

In my job, I spend 99% of my time thinking about ethical issues that arise in the care of human beings. That is the focus of our medical school, and that’s what we do.

However,

Recently, there has been a great increase in the number of pet owners who are saying, “I’m not going to vaccinate my pets.” As horrible as this sounds, what’s happening is vaccine hesitancy about vaccines used in humans is extending through some people to their pets.

The number of people who say they don’t trust things like rabies vaccine to be effective or safe for their pet animals is 40%, at least in surveys, and the American Veterinary Medical Association reports that 15%-18% of pet owners are not, in fact, vaccinating their pets against rabies.

Rabies, as I hope everybody knows, is one horrible disease. Even the treatment of it, should you get bitten by a rabid animal, is no fun, expensive, and hopefully something that can be administered quickly. It’s not always the case. Worldwide, at least 70,000 people die from rabies every year.

Obviously, there are many countries that are so terrified of rabies, they won’t let you bring pets in without quarantining them, say, England, for at least 6 months to a year, I believe, because they don’t want rabies getting into their country. They’re very strict about the movement of pets.

It is inexcusable for people, first, not to give their pets vaccines that prevent them getting distemper, parvovirus, or many other diseases that harm the pet. It’s also inexcusable to shorten your pet’s life or ask your patients to care for pets who get sick from many of these diseases that are vaccine preventable.

Worst of all, it’s inexcusable for any pet owner not to give a rabies vaccine to their pets. Were it up to me, I’d say you have to license your pet, and as part of that, you must mandate rabies vaccines for your dogs, cats, and other pets.

We know what happens when people encounter wild animals like raccoons and rabbits. It is not a good situation. Your pets can easily encounter a rabid animal and then put themselves in a position where they can harm their human owners.

We have an efficacious, safe treatment. If you’re dealing with someone, it might make sense to ask them, “Do you own a pet? Are you vaccinating?” It may not be something you’d ever thought about, but what we don’t need is rabies back in a bigger way in the United States than it’s been in the past.

I think, as a matter of prudence and public health, maybe firing up that question, “Got a pet in the house and are you vaccinating,” could be part of taking a good history.

Dr. Caplan is director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Center, New York City. He disclosed conflicts of interest with Johnson & Johnson and Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The New Formula for Stronger, Longer-Lasting Vaccines

Vaccines work pretty well. But with a little help, they could work better.

Stanford researchers have developed a new vaccine helper that combines two kinds of adjuvants, ingredients that improve a vaccine’s efficacy, in a novel, customizable system.

In lab tests, the experimental additive improved the effectiveness of COVID-19 and HIV vaccine candidates, though it could be adapted to stimulate immune responses to a variety of pathogens, the researchers said. It could also be used one day to fine-tune vaccines for vulnerable groups like young children, older adults, and those with compromised immune systems.

“Current vaccines are not perfect,” said lead study author Ben Ou, a PhD candidate and researcher in the lab of Eric Appel, PhD, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, at Stanford University in California. “Many fail to generate long-lasting immunity or immunity against closely related strains [such as] flu or COVID vaccines. One way to improve them is to design more potent vaccine adjuvants.”

The study marks an advance in an area of growing scientific interest: Combining different adjuvants to enhance the immune-stimulating effect.

The Stanford scientists developed sphere-shaped nanoparticles, like tiny round cages, made of saponins, immune-stimulating molecules common in adjuvant development. To these nanoparticles, they attached Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, molecules that have become a focus in vaccine research because they stimulate a variety of immune responses.

Dr. Ou and the team tested the new adjuvant platform in COVID and HIV vaccines, comparing it to vaccines containing alum, a widely used adjuvant. (Alum is not used in COVID vaccines available in the United States.)

The nanoparticle-adjuvanted vaccines triggered stronger, longer-lasting effects.

Notably, the combination of the new adjuvant system with a SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccine was effective in mice against the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and against Delta, Omicron, and other variants that emerged in the months and years after the initial outbreak.

“Since our nanoparticle adjuvant platform is more potent than traditional/clinical vaccine adjuvants,” Dr. Ou said, “we expected mice to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies and better breadth responses.”

100 Years of Adjuvants

The first vaccine adjuvants were aluminum salts mixed into shots against pertussis, diphtheria, and tetanus in the 1920s. Today, alum is still used in many vaccines, including shots for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis; hepatitis A and B; human papillomavirus; and pneumococcal disease.

But since the 1990s, new adjuvants have come on the scene. Saponin-based compounds, harvested from the soapbark tree, are used in the Novavax COVID-19 Vaccine, Adjuvanted; a synthetic DNA adjuvant in the Heplisav-B vaccine against hepatitis B; and oil in water adjuvants using squalene in the Fluad and Fluad Quadrivalent influenza vaccines. Other vaccines, including those for chickenpox, cholera, measles, mumps, rubella, and mRNA-based COVID vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, don’t contain adjuvants.

TLR agonists have recently become research hotspots in vaccine science.

“TLR agonists activate the innate immune system, putting it on a heightened alert state that can result in a higher antibody production and longer-lasting protection,” said David Burkhart, PhD, a research professor in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Montana in Missoula. He is also the chief operating officer of Inimmune, a biotech company developing vaccines and immunotherapies.

Dr. Burkhart studies TLR agonists in vaccines and other applications. “Different combinations activate different parts of the immune system,” he said. “TLR4 might activate the army, while TLR7 might activate the air force. You might need both in one vaccine.”

TLR agonists have also shown promise against Alzheimer’s disease, allergies, cancer, and even addiction. In immune’s experimental immunotherapy using TLR agonists for advanced solid tumors has just entered human trials, and the company is looking at a TLR agonist therapy for allergic rhinitis.

Combining Forces

In the new study, researchers tested five different combinations of TLR agonists hooked to the saponin nanoparticle framework. Each elicited a slightly different response from the immune cells.

“Our immune systems generate different downstream immune responses based on which TLRs are activated,” Dr. Ou said.

Ultimately, the advance could spur the development of vaccines tuned for stronger immune protection.

“We need different immune responses to fight different types of pathogens,” Dr. Ou said. “Depending on what specific virus/disease the vaccine is formulated for, activation of one specific TLR may confer better protection than another TLR.”

According to Dr. Burkhart, combining a saponin with a TLR agonist has found success before.

Biopharma company GSK (formerly GlaxoSmithKline) used the combination in its AS01 adjuvant, in the vaccine Shingrix against herpes zoster. The live-attenuated yellow fever vaccine, given to more than 600 million people around the world and considered one of the most powerful vaccines ever developed, uses several TLR agonists.

The Stanford paper, Dr. Burkhart said, “is a nice demonstration of the enhanced efficacy [that] adjuvants can provide to vaccines by exploiting the synergy different adjuvants and TLR agonists can provide when used in combination.”

Tailoring Vaccines

The customizable aspect of TLR agonists is important too, Dr. Burkhart said.

“The human immune system changes dramatically from birth to childhood into adulthood into older maturity,” he said. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all. Vaccines need to be tailored to these populations for maximum effectiveness and safety. TLRAs [TLR agonists] are a highly valuable tool in the vaccine toolbox. I think it’s inevitable we’ll have more in the future.”

That’s what the Stanford researchers hope for.

They noted in the study that the nanoparticle platform could easily be used to test different TLR agonist adjuvant combinations in vaccines.

But human studies are still a ways off. Tests in larger animals would likely come next, Dr. Ou said.

“We now have a single nanoparticle adjuvant platform with formulations containing different TLRs,” Dr. Ou said. “Scientists can pick which specific formulation is the most suitable for their needs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaccines work pretty well. But with a little help, they could work better.

Stanford researchers have developed a new vaccine helper that combines two kinds of adjuvants, ingredients that improve a vaccine’s efficacy, in a novel, customizable system.

In lab tests, the experimental additive improved the effectiveness of COVID-19 and HIV vaccine candidates, though it could be adapted to stimulate immune responses to a variety of pathogens, the researchers said. It could also be used one day to fine-tune vaccines for vulnerable groups like young children, older adults, and those with compromised immune systems.

“Current vaccines are not perfect,” said lead study author Ben Ou, a PhD candidate and researcher in the lab of Eric Appel, PhD, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, at Stanford University in California. “Many fail to generate long-lasting immunity or immunity against closely related strains [such as] flu or COVID vaccines. One way to improve them is to design more potent vaccine adjuvants.”

The study marks an advance in an area of growing scientific interest: Combining different adjuvants to enhance the immune-stimulating effect.

The Stanford scientists developed sphere-shaped nanoparticles, like tiny round cages, made of saponins, immune-stimulating molecules common in adjuvant development. To these nanoparticles, they attached Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, molecules that have become a focus in vaccine research because they stimulate a variety of immune responses.

Dr. Ou and the team tested the new adjuvant platform in COVID and HIV vaccines, comparing it to vaccines containing alum, a widely used adjuvant. (Alum is not used in COVID vaccines available in the United States.)

The nanoparticle-adjuvanted vaccines triggered stronger, longer-lasting effects.

Notably, the combination of the new adjuvant system with a SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccine was effective in mice against the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and against Delta, Omicron, and other variants that emerged in the months and years after the initial outbreak.

“Since our nanoparticle adjuvant platform is more potent than traditional/clinical vaccine adjuvants,” Dr. Ou said, “we expected mice to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies and better breadth responses.”

100 Years of Adjuvants

The first vaccine adjuvants were aluminum salts mixed into shots against pertussis, diphtheria, and tetanus in the 1920s. Today, alum is still used in many vaccines, including shots for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis; hepatitis A and B; human papillomavirus; and pneumococcal disease.

But since the 1990s, new adjuvants have come on the scene. Saponin-based compounds, harvested from the soapbark tree, are used in the Novavax COVID-19 Vaccine, Adjuvanted; a synthetic DNA adjuvant in the Heplisav-B vaccine against hepatitis B; and oil in water adjuvants using squalene in the Fluad and Fluad Quadrivalent influenza vaccines. Other vaccines, including those for chickenpox, cholera, measles, mumps, rubella, and mRNA-based COVID vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, don’t contain adjuvants.

TLR agonists have recently become research hotspots in vaccine science.

“TLR agonists activate the innate immune system, putting it on a heightened alert state that can result in a higher antibody production and longer-lasting protection,” said David Burkhart, PhD, a research professor in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Montana in Missoula. He is also the chief operating officer of Inimmune, a biotech company developing vaccines and immunotherapies.

Dr. Burkhart studies TLR agonists in vaccines and other applications. “Different combinations activate different parts of the immune system,” he said. “TLR4 might activate the army, while TLR7 might activate the air force. You might need both in one vaccine.”

TLR agonists have also shown promise against Alzheimer’s disease, allergies, cancer, and even addiction. In immune’s experimental immunotherapy using TLR agonists for advanced solid tumors has just entered human trials, and the company is looking at a TLR agonist therapy for allergic rhinitis.

Combining Forces

In the new study, researchers tested five different combinations of TLR agonists hooked to the saponin nanoparticle framework. Each elicited a slightly different response from the immune cells.

“Our immune systems generate different downstream immune responses based on which TLRs are activated,” Dr. Ou said.

Ultimately, the advance could spur the development of vaccines tuned for stronger immune protection.

“We need different immune responses to fight different types of pathogens,” Dr. Ou said. “Depending on what specific virus/disease the vaccine is formulated for, activation of one specific TLR may confer better protection than another TLR.”

According to Dr. Burkhart, combining a saponin with a TLR agonist has found success before.

Biopharma company GSK (formerly GlaxoSmithKline) used the combination in its AS01 adjuvant, in the vaccine Shingrix against herpes zoster. The live-attenuated yellow fever vaccine, given to more than 600 million people around the world and considered one of the most powerful vaccines ever developed, uses several TLR agonists.

The Stanford paper, Dr. Burkhart said, “is a nice demonstration of the enhanced efficacy [that] adjuvants can provide to vaccines by exploiting the synergy different adjuvants and TLR agonists can provide when used in combination.”

Tailoring Vaccines

The customizable aspect of TLR agonists is important too, Dr. Burkhart said.

“The human immune system changes dramatically from birth to childhood into adulthood into older maturity,” he said. “It’s not a one-size-fits-all. Vaccines need to be tailored to these populations for maximum effectiveness and safety. TLRAs [TLR agonists] are a highly valuable tool in the vaccine toolbox. I think it’s inevitable we’ll have more in the future.”

That’s what the Stanford researchers hope for.

They noted in the study that the nanoparticle platform could easily be used to test different TLR agonist adjuvant combinations in vaccines.

But human studies are still a ways off. Tests in larger animals would likely come next, Dr. Ou said.

“We now have a single nanoparticle adjuvant platform with formulations containing different TLRs,” Dr. Ou said. “Scientists can pick which specific formulation is the most suitable for their needs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaccines work pretty well. But with a little help, they could work better.

Stanford researchers have developed a new vaccine helper that combines two kinds of adjuvants, ingredients that improve a vaccine’s efficacy, in a novel, customizable system.

In lab tests, the experimental additive improved the effectiveness of COVID-19 and HIV vaccine candidates, though it could be adapted to stimulate immune responses to a variety of pathogens, the researchers said. It could also be used one day to fine-tune vaccines for vulnerable groups like young children, older adults, and those with compromised immune systems.

“Current vaccines are not perfect,” said lead study author Ben Ou, a PhD candidate and researcher in the lab of Eric Appel, PhD, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, at Stanford University in California. “Many fail to generate long-lasting immunity or immunity against closely related strains [such as] flu or COVID vaccines. One way to improve them is to design more potent vaccine adjuvants.”

The study marks an advance in an area of growing scientific interest: Combining different adjuvants to enhance the immune-stimulating effect.

The Stanford scientists developed sphere-shaped nanoparticles, like tiny round cages, made of saponins, immune-stimulating molecules common in adjuvant development. To these nanoparticles, they attached Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, molecules that have become a focus in vaccine research because they stimulate a variety of immune responses.

Dr. Ou and the team tested the new adjuvant platform in COVID and HIV vaccines, comparing it to vaccines containing alum, a widely used adjuvant. (Alum is not used in COVID vaccines available in the United States.)

The nanoparticle-adjuvanted vaccines triggered stronger, longer-lasting effects.

Notably, the combination of the new adjuvant system with a SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccine was effective in mice against the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and against Delta, Omicron, and other variants that emerged in the months and years after the initial outbreak.

“Since our nanoparticle adjuvant platform is more potent than traditional/clinical vaccine adjuvants,” Dr. Ou said, “we expected mice to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies and better breadth responses.”

100 Years of Adjuvants

The first vaccine adjuvants were aluminum salts mixed into shots against pertussis, diphtheria, and tetanus in the 1920s. Today, alum is still used in many vaccines, including shots for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis; hepatitis A and B; human papillomavirus; and pneumococcal disease.

But since the 1990s, new adjuvants have come on the scene. Saponin-based compounds, harvested from the soapbark tree, are used in the Novavax COVID-19 Vaccine, Adjuvanted; a synthetic DNA adjuvant in the Heplisav-B vaccine against hepatitis B; and oil in water adjuvants using squalene in the Fluad and Fluad Quadrivalent influenza vaccines. Other vaccines, including those for chickenpox, cholera, measles, mumps, rubella, and mRNA-based COVID vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, don’t contain adjuvants.

TLR agonists have recently become research hotspots in vaccine science.

“TLR agonists activate the innate immune system, putting it on a heightened alert state that can result in a higher antibody production and longer-lasting protection,” said David Burkhart, PhD, a research professor in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Montana in Missoula. He is also the chief operating officer of Inimmune, a biotech company developing vaccines and immunotherapies.

Dr. Burkhart studies TLR agonists in vaccines and other applications. “Different combinations activate different parts of the immune system,” he said. “TLR4 might activate the army, while TLR7 might activate the air force. You might need both in one vaccine.”

TLR agonists have also shown promise against Alzheimer’s disease, allergies, cancer, and even addiction. In immune’s experimental immunotherapy using TLR agonists for advanced solid tumors has just entered human trials, and the company is looking at a TLR agonist therapy for allergic rhinitis.

Combining Forces

In the new study, researchers tested five different combinations of TLR agonists hooked to the saponin nanoparticle framework. Each elicited a slightly different response from the immune cells.

“Our immune systems generate different downstream immune responses based on which TLRs are activated,” Dr. Ou said.

Ultimately, the advance could spur the development of vaccines tuned for stronger immune protection.

“We need different immune responses to fight different types of pathogens,” Dr. Ou said. “Depending on what specific virus/disease the vaccine is formulated for, activation of one specific TLR may confer better protection than another TLR.”