User login

Living donor liver transplants on rise for most urgent need

Living donor liver transplants (LDLT) for recipients with the most urgent need for a liver transplant in the next 3 months – a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 25 or higher – have become more frequent during the past decade, according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Among LDLT recipients, researchers found comparable patient and graft survival at low and high MELD scores. But among patients with high MELD scores, researchers found lower adjusted graft survival and a higher transplant rate among those with living donors, compared with recipients of deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT).

The findings suggest certain advantages of LDLT over DDLT may be lost in the high-MELD setting in terms of graft survival, said Benjamin Rosenthal, MD, an internal medicine resident focused on transplant hepatology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Historically, in the United States especially, living donor liver transplantation has been offered to patients with low or moderate MELD,” he said. “The outcomes of LDLT at high MELD are currently unknown.”

Previous data from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study (A2ALL) found that LDLT offered a survival benefit versus remaining on the wait list, independent of MELD score, he said. A recent study also has demonstrated a survival benefit across MELD scores of 11-26, but findings for MELD scores of 25 and higher have been mixed.

Trends and outcomes in LDLT at high MELD scores

Dr. Rosenthal and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult LDLT recipients from 2010 to 2021 using data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), the U.S. donation and transplantation system.

In baseline characteristics among LDLT transplant recipients, there weren’t significant differences in age, sex, race, and ethnicity for MELD scores below 25 or at 25 and higher. There also weren’t significant differences in donor age, relationship, use of nondirected grafts, or percentage of right and left lobe donors for LDLT recipients. However, recipients with high MELD scores had more nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (29.5% versus 24.6%) and alcohol-assisted cirrhosis (21.6% versus 14.3%).

The research team evaluated graft survival among LDLT recipients by MELD below 25 and at 25 or higher. They also compared posttransplant patient and graft survival between LDLT and DDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. They excluded transplant candidates on the wait list for Status 1/1A, redo transplant, or multiorgan transplant.

Among the 3,590 patients who had LDLT between 2010 and 2021, 342 patients (9.5%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant. There was some progression during the waiting period, Dr. Rosenthal noted, with a median listing MELD score of 19 among those who had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant and 21 among those who had a MELD of 30 or higher at transplant.

For LDLT recipients with MELD scores above or below 25, researchers found no significant differences in adjusted patient survival or adjusted graft survival.

Then the team compared outcomes of LDLT and DDLT in high-MELD recipients. Among the 67,279-patient DDLT comparator group, 27,552 patients (41%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant.

In terms of LDLT versus DDLT, unadjusted and adjusted patient survival were no different for patients with MELD of 25 or higher. In addition, unadjusted graft survival was no different.

However, adjusted graft survival was worse for LDLT recipients with high MELD scores. In addition, the retransplant rate was higher in LDLT recipients, at 5.7% versus 2.4%.

The reason why graft survival may be worse remains unclear, Dr. Rosenthal said. One hypothesis is that a low graft-to-recipient weight ratio in LDLT can cause small-for-size syndrome. However, these ratios were not available from OPTN.

“Further studies should be done to see what the benefit is, with graft-to-recipient weight ratios included,” he said. “The differences between DDLT and LDLT in this setting should be further explored as well.”

The research team also described temporal and transplant center trends for LDLT by MELD group. For temporal trends, they expanded the study period from 2002-2021.

The found a marked U.S. increase in the percentage of LDLT with a MELD of 25 or higher, particularly in the last decade and especially in the last 5 years. But the percentage of LDLT with high MELD remains lower than 15%, even in recent years, Dr. Rosenthal noted.

Across transplant centers, there was a trend toward centers with increasing LDLT volume having a greater proportion of LDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. At the 19.6% of centers performing 10 or fewer LDLT during the study period, none of the LDLT recipients had a MELD of 25 or higher, Dr. Rosenthal said.

The authors didn’t report a funding source. The authors declared no relevant disclosures.

Living donor liver transplants (LDLT) for recipients with the most urgent need for a liver transplant in the next 3 months – a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 25 or higher – have become more frequent during the past decade, according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Among LDLT recipients, researchers found comparable patient and graft survival at low and high MELD scores. But among patients with high MELD scores, researchers found lower adjusted graft survival and a higher transplant rate among those with living donors, compared with recipients of deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT).

The findings suggest certain advantages of LDLT over DDLT may be lost in the high-MELD setting in terms of graft survival, said Benjamin Rosenthal, MD, an internal medicine resident focused on transplant hepatology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Historically, in the United States especially, living donor liver transplantation has been offered to patients with low or moderate MELD,” he said. “The outcomes of LDLT at high MELD are currently unknown.”

Previous data from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study (A2ALL) found that LDLT offered a survival benefit versus remaining on the wait list, independent of MELD score, he said. A recent study also has demonstrated a survival benefit across MELD scores of 11-26, but findings for MELD scores of 25 and higher have been mixed.

Trends and outcomes in LDLT at high MELD scores

Dr. Rosenthal and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult LDLT recipients from 2010 to 2021 using data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), the U.S. donation and transplantation system.

In baseline characteristics among LDLT transplant recipients, there weren’t significant differences in age, sex, race, and ethnicity for MELD scores below 25 or at 25 and higher. There also weren’t significant differences in donor age, relationship, use of nondirected grafts, or percentage of right and left lobe donors for LDLT recipients. However, recipients with high MELD scores had more nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (29.5% versus 24.6%) and alcohol-assisted cirrhosis (21.6% versus 14.3%).

The research team evaluated graft survival among LDLT recipients by MELD below 25 and at 25 or higher. They also compared posttransplant patient and graft survival between LDLT and DDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. They excluded transplant candidates on the wait list for Status 1/1A, redo transplant, or multiorgan transplant.

Among the 3,590 patients who had LDLT between 2010 and 2021, 342 patients (9.5%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant. There was some progression during the waiting period, Dr. Rosenthal noted, with a median listing MELD score of 19 among those who had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant and 21 among those who had a MELD of 30 or higher at transplant.

For LDLT recipients with MELD scores above or below 25, researchers found no significant differences in adjusted patient survival or adjusted graft survival.

Then the team compared outcomes of LDLT and DDLT in high-MELD recipients. Among the 67,279-patient DDLT comparator group, 27,552 patients (41%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant.

In terms of LDLT versus DDLT, unadjusted and adjusted patient survival were no different for patients with MELD of 25 or higher. In addition, unadjusted graft survival was no different.

However, adjusted graft survival was worse for LDLT recipients with high MELD scores. In addition, the retransplant rate was higher in LDLT recipients, at 5.7% versus 2.4%.

The reason why graft survival may be worse remains unclear, Dr. Rosenthal said. One hypothesis is that a low graft-to-recipient weight ratio in LDLT can cause small-for-size syndrome. However, these ratios were not available from OPTN.

“Further studies should be done to see what the benefit is, with graft-to-recipient weight ratios included,” he said. “The differences between DDLT and LDLT in this setting should be further explored as well.”

The research team also described temporal and transplant center trends for LDLT by MELD group. For temporal trends, they expanded the study period from 2002-2021.

The found a marked U.S. increase in the percentage of LDLT with a MELD of 25 or higher, particularly in the last decade and especially in the last 5 years. But the percentage of LDLT with high MELD remains lower than 15%, even in recent years, Dr. Rosenthal noted.

Across transplant centers, there was a trend toward centers with increasing LDLT volume having a greater proportion of LDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. At the 19.6% of centers performing 10 or fewer LDLT during the study period, none of the LDLT recipients had a MELD of 25 or higher, Dr. Rosenthal said.

The authors didn’t report a funding source. The authors declared no relevant disclosures.

Living donor liver transplants (LDLT) for recipients with the most urgent need for a liver transplant in the next 3 months – a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score of 25 or higher – have become more frequent during the past decade, according to new findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Among LDLT recipients, researchers found comparable patient and graft survival at low and high MELD scores. But among patients with high MELD scores, researchers found lower adjusted graft survival and a higher transplant rate among those with living donors, compared with recipients of deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT).

The findings suggest certain advantages of LDLT over DDLT may be lost in the high-MELD setting in terms of graft survival, said Benjamin Rosenthal, MD, an internal medicine resident focused on transplant hepatology at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Historically, in the United States especially, living donor liver transplantation has been offered to patients with low or moderate MELD,” he said. “The outcomes of LDLT at high MELD are currently unknown.”

Previous data from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study (A2ALL) found that LDLT offered a survival benefit versus remaining on the wait list, independent of MELD score, he said. A recent study also has demonstrated a survival benefit across MELD scores of 11-26, but findings for MELD scores of 25 and higher have been mixed.

Trends and outcomes in LDLT at high MELD scores

Dr. Rosenthal and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of adult LDLT recipients from 2010 to 2021 using data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), the U.S. donation and transplantation system.

In baseline characteristics among LDLT transplant recipients, there weren’t significant differences in age, sex, race, and ethnicity for MELD scores below 25 or at 25 and higher. There also weren’t significant differences in donor age, relationship, use of nondirected grafts, or percentage of right and left lobe donors for LDLT recipients. However, recipients with high MELD scores had more nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (29.5% versus 24.6%) and alcohol-assisted cirrhosis (21.6% versus 14.3%).

The research team evaluated graft survival among LDLT recipients by MELD below 25 and at 25 or higher. They also compared posttransplant patient and graft survival between LDLT and DDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. They excluded transplant candidates on the wait list for Status 1/1A, redo transplant, or multiorgan transplant.

Among the 3,590 patients who had LDLT between 2010 and 2021, 342 patients (9.5%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant. There was some progression during the waiting period, Dr. Rosenthal noted, with a median listing MELD score of 19 among those who had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant and 21 among those who had a MELD of 30 or higher at transplant.

For LDLT recipients with MELD scores above or below 25, researchers found no significant differences in adjusted patient survival or adjusted graft survival.

Then the team compared outcomes of LDLT and DDLT in high-MELD recipients. Among the 67,279-patient DDLT comparator group, 27,552 patients (41%) had a MELD of 25 or higher at transplant.

In terms of LDLT versus DDLT, unadjusted and adjusted patient survival were no different for patients with MELD of 25 or higher. In addition, unadjusted graft survival was no different.

However, adjusted graft survival was worse for LDLT recipients with high MELD scores. In addition, the retransplant rate was higher in LDLT recipients, at 5.7% versus 2.4%.

The reason why graft survival may be worse remains unclear, Dr. Rosenthal said. One hypothesis is that a low graft-to-recipient weight ratio in LDLT can cause small-for-size syndrome. However, these ratios were not available from OPTN.

“Further studies should be done to see what the benefit is, with graft-to-recipient weight ratios included,” he said. “The differences between DDLT and LDLT in this setting should be further explored as well.”

The research team also described temporal and transplant center trends for LDLT by MELD group. For temporal trends, they expanded the study period from 2002-2021.

The found a marked U.S. increase in the percentage of LDLT with a MELD of 25 or higher, particularly in the last decade and especially in the last 5 years. But the percentage of LDLT with high MELD remains lower than 15%, even in recent years, Dr. Rosenthal noted.

Across transplant centers, there was a trend toward centers with increasing LDLT volume having a greater proportion of LDLT recipients with a MELD of 25 or higher. At the 19.6% of centers performing 10 or fewer LDLT during the study period, none of the LDLT recipients had a MELD of 25 or higher, Dr. Rosenthal said.

The authors didn’t report a funding source. The authors declared no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING

Have you heard the one about the emergency dept. that called 911?

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

Who watches the ED staff?

We heard a really great joke recently, one we simply have to share.

A man in Seattle went to a therapist. “I’m depressed,” he says. “Depressed, overworked, and lonely.”

“Oh dear, that sounds quite serious,” the therapist replies. “Tell me all about it.”

“Life just seems so harsh and cruel,” the man explains. “The pandemic has caused 300,000 health care workers across the country to leave the industry.”

“Such as the doctor typically filling this role in the joke,” the therapist, who is not licensed to prescribe medicine, nods.

“Exactly! And with so many respiratory viruses circulating and COVID still hanging around, emergency departments all over the country are facing massive backups. People are waiting outside the hospital for hours, hoping a bed will open up. Things got so bad at a hospital near Seattle in October that a nurse called 911 on her own ED. Told the 911 operator to send the fire department to help out, since they were ‘drowning’ and ‘in dire straits.’ They had 45 patients waiting and only five nurses to take care of them.”

“That is quite serious,” the therapist says, scribbling down unseen notes.

“The fire chief did send a crew out, and they cleaned rooms, changed beds, and took vitals for 90 minutes until the crisis passed,” the man says. “But it’s only a matter of time before it happens again. The hospital president said they have 300 open positions, and literally no one has applied to work in the emergency department. Not one person.”

“And how does all this make you feel?” the therapist asks.

“I feel all alone,” the man says. “This world feels so threatening, like no one cares, and I have no idea what will come next. It’s so vague and uncertain.”

“Ah, I think I have a solution for you,” the therapist says. “Go to the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center in Silverdale, near Seattle. They’ll get your bad mood all settled, and they’ll prescribe you the medicine you need to relax.”

The man bursts into tears. “You don’t understand,” he says. “I am the emergency department at St. Michael Medical Center.”

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

Myth buster: Supplements for cholesterol lowering

When it comes to that nasty low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, some people swear by supplements over statins as a holistic approach. Well, we’re busting the myth that those heart-healthy supplements are even effective in comparison.

Which supplements are we talking about? These six are always on sale at the pharmacy: fish oil, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, plant sterols, and red yeast rice.

In a study presented at the recent American Heart Association scientific sessions, researchers compared these supplements’ effectiveness in lowering LDL cholesterol with low-dose rosuvastatin or placebo among 199 adults aged 40-75 years who didn’t have a personal history of cardiovascular disease.

Participants who took the statin for 28 days had an average of 24% decrease in total cholesterol and a 38% reduction in LDL cholesterol, while 28 days’ worth of the supplements did no better than the placebo in either measure. Compared with placebo, the plant sterols supplement notably lowered HDL cholesterol and the garlic supplement notably increased LDL cholesterol.

Even though there are other studies showing the validity of plant sterols and red yeast rice to lower LDL cholesterol, author Luke J. Laffin, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic noted that this study shows how supplement results can vary and that more research is needed to see the effect they truly have on cholesterol over time.

So, should you stop taking or recommending supplements for heart health or healthy cholesterol levels? Well, we’re not going to come to your house and raid your medicine cabinet, but the authors of this study are definitely not saying that you should rely on them.

Consider this myth mostly busted.

COVID dept. of unintended consequences, part 2

The surveillance testing programs conducted in the first year of the pandemic were, in theory, meant to keep everyone safer. Someone, apparently, forgot to explain that to the students of the University of Wyoming and the University of Idaho.

We’re all familiar with the drill: Students at the two schools had to undergo frequent COVID screening to keep the virus from spreading, thereby making everyone safer. Duck your head now, because here comes the unintended consequence.

The students who didn’t get COVID eventually, and perhaps not so surprisingly, “perceived that the mandatory testing policy decreased their risk of contracting COVID-19, and … this perception led to higher participation in COVID-risky events,” Chian Jones Ritten, PhD, and associates said in PNAS Nexus.

They surveyed 757 students from the Univ. of Washington and 517 from the Univ. of Idaho and found that those who were tested more frequently perceived that they were less likely to contract the virus. Those respondents also more frequently attended indoor gatherings, both small and large, and spent more time in restaurants and bars.

The investigators did not mince words: “From a public health standpoint, such behavior is problematic.”

Current parents/participants in the workforce might have other ideas about an appropriate response to COVID.

At this point, we probably should mention that appropriation is the second-most sincere form of flattery.

A Patient Presenting With Shortness of Breath, Fever, and Eosinophilia

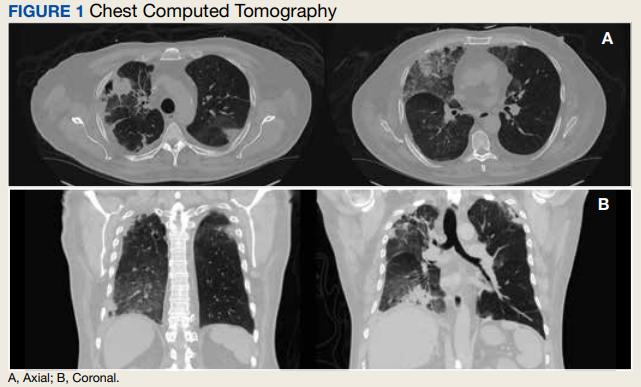

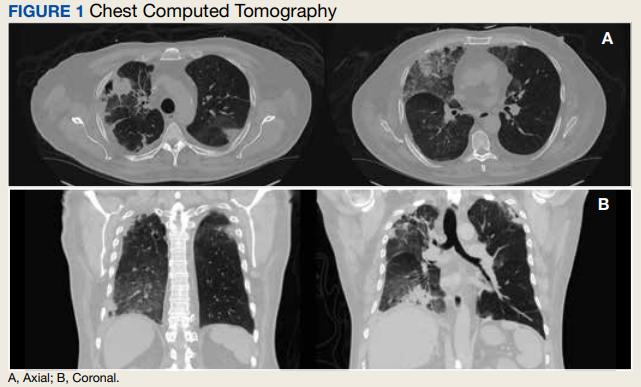

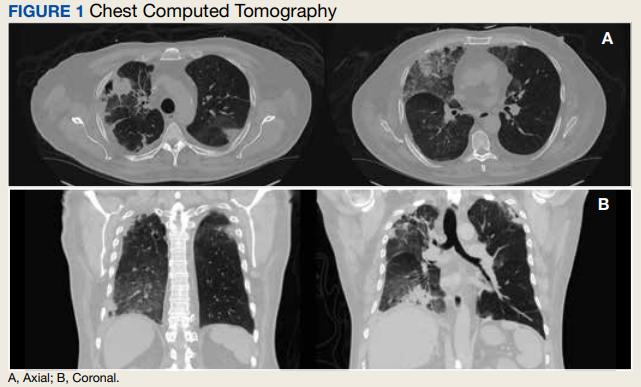

A 70-year-old veteran with a history notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, complicated by peripheral neuropathy and bilateral foot ulceration, and previous pulmonary tuberculosis (treated in June 2013) presented to an outside medical facility with bilateral worsening foot pain, swelling, and drainage of preexisting ulcers. He received a diagnosis of bilateral fifth toe osteomyelitis and was discharged with a 6-week course of IV daptomycin 600 mg (8 mg/kg) and ertapenem 1 g/d. At discharge, the patient was in stable condition. Follow-up was done by our outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) team, which consists of an infectious disease pharmacist and the physician director of antimicrobial stewardship who monitor veterans receiving outpatient IV antibiotic therapy.1

Three weeks later as part of the regular OPAT surveillance, the patient reported via telephone that his foot osteomyelitis was stable, but he had a 101 °F fever and a new cough. He was instructed to come to the emergency department (ED) immediately. On arrival,

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

In the ED, the patient was given a provisional diagnosis of multifocal bacterial pneumonia and was admitted to the hospital for further management. His outpatient regimen of IV daptomycin and ertapenem was adjusted to IV vancomycin and meropenem. The infectious disease service was consulted within 24 hours of admission, and based on the new onset chest infiltrates, therapy with daptomycin and notable peripheral blood eosinophilia, a presumptive diagnosis of daptomycin-related acute eosinophilic pneumonia was made. A medication list review yielded no other potential etiologic agents for drug-related eosinophilia, and the patient did not have any remote or recent pertinent travel history concerning for parasitic disease.

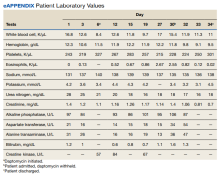

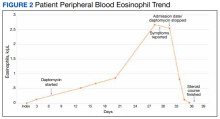

The patient was treated with oral prednisone 40 mg (0.5 mg/kg) daily and the daptomycin was not restarted. Within 24 hours, the patient’s fevers, oxygen requirements, and cough subsided. Laboratory values

Discussion

Daptomycin is a commonly used cyclic lipopeptide IV antibiotic with broad activity against gram-positive organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). Daptomycin has emerged as a convenient alternative for infections typically treated with IV vancomycin: shorter infusion time (2-30 minutes vs 60-180 minutes), daily administration, and less need for dose adjustments. A recent survey reported higher satisfaction and less disruption in patients receiving daptomycin compared with vancomycin.2 The main daptomycin-specific adverse effect (AE) that warrants close monitoring is elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels and skeletal muscle breakdown (reversible after holding medication).3 Other rarely reported AEs include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), acute eosinophilic pneumonitis, hepatitis, and peripheral neuropathy.4-6 Consequently, weekly monitoring for this drug should include symptom inquiry for cough and muscle pain, and laboratory testing with CBC with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and CK.

Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia has been described in several case reports and in a recent study, the frequency of this event was almost 5% in those receiving long-term daptomycin therapy.7 The most common symptoms include dyspnea, fever, infiltrates/opacities on chest imaging, and peripheral eosinophilia. It is theorized that the chemical structure of daptomycin causes immune-mediated pulmonary epithelial cell injury with eosinophils, resulting in increased peripheral eosinophilia.3 Risk factors that have been identified for daptomycin-induced eosinophilia include age > 70 years; the presence of comorbidities of heart and pulmonary disease; duration of daptomycin beyond 2 weeks; and cumulative doses over 10 g. Average onset of illness from initiation of daptomycin has been reported to be about 3 weeks.7,8 The diagnosis of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonitis is made on several criteria per the FDA. These include exposure to daptomycin, fever, dyspnea with oxygen requirement, new infiltrates on imaging, bronchoalveolar lavage with > 25% eosinophils, and last, clinical improvement on removal of the drug.9 However, as bronchoscopy is an invasive diagnostic modality, it is not always performed or necessary as seen in this case. Furthermore, not all patients will have peripheral eosinophilia, with only 77% of patients having that finding in a systematic review.10 Taken together, the overall true incidence of daptomycin-induced eosinophilia may be underestimated. Treatment involves discontinuation of the daptomycin and initiation of steroids. In a review of 35 cases, the majority did receive systemic steroids, usually 60 to 125 mg of IV methylprednisolone every 6 hours, which was converted to oral steroids and tapered over 2 to 6 weeks.10 However, all patients including those who did not receive steroids had symptom improvement or complete resolution, highlighting that prompt discontinuation of daptomycin is the most crucial intervention.

Conclusions

As home IV antibiotic therapy becomes increasingly used to facilitate shorter lengths of stay in hospitals and enable more patients to receive their infectious disease care at home, the general practitioner must be aware of the potential AEs of commonly used IV antibiotics. While acute cutaneous reactions and disturbances in renal and liver function are commonly recognized entities of adverse drug reactions, symptoms of fever and cough are more likely to be interpreted as acute viral or bacterial respiratory infections. A high index of clinical suspicion is needed for eosinophilic pneumonitis secondary to daptomycin. A simple and readily available test, such as a CBC with differential may facilitate the identification of this potentially serious AE, allowing prompt discontinuation of the drug.

1. Kent M, Kouma M, Jodlowski T, Cutrell JB. 755. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy program evaluation within a large Veterans Affairs healthcare system. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(suppl 2):S337. Published 2019 Oct 23. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz360.823

2. Wu KH, Sakoulas G, Geriak M. Vancomycin or daptomycin for outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy: does it make a difference in patient satisfaction? Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(8):ofab418. Published 2021 Aug 30. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab418

3. Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Seaton RA, Hamed K. Daptomycin: an evidence-based review of its role in the treatment of gram-positive infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2016;9:47-58. Published 2016 Apr 15. doi:10.2147/IDR.S99046

4. Sharifzadeh S, Mohammadpour AH, Tavanaee A, Elyasi S. Antibacterial antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: a literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77(3):275-289. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-03005-9

5. Mo Y, Nehring F, Jung AH, Housman ST. Possible hepatotoxicity associated with daptomycin: a case report and literature review. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(3):253-256. doi:10.1177/0897190015625403

6. Villaverde Piñeiro L, Rabuñal Rey R, García Sabina A, Monte Secades R, García Pais MJ. Paralysis of the external popliteal sciatic nerve associated with daptomycin administration. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(4):578-580. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12666

7. Soldevila-Boixader L, Villanueva B, Ulldemolins M, et al. Risk factors of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in a population with osteoarticular infection. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(4):446. Published 2021 Apr 16. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10040446

8. Kumar S, Acosta-Sanchez I, Rajagopalan N. Daptomycin-induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2899. Published 2018 Jun 30. doi:10.7759/cureus.2899

9. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Eosinophilic pneumonia associated with the use of cubicin. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 3, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fda-drug-safety-communication-eosinophilic-pneumonia-associated-use-cubicin-daptomycin

10. Uppal P, LaPlante KL, Gaitanis MM, Jankowich MD, Ward KE. Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia—a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:55. Published 2016 Dec 12. doi:10.1186/s13756-016-0158-8

A 70-year-old veteran with a history notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, complicated by peripheral neuropathy and bilateral foot ulceration, and previous pulmonary tuberculosis (treated in June 2013) presented to an outside medical facility with bilateral worsening foot pain, swelling, and drainage of preexisting ulcers. He received a diagnosis of bilateral fifth toe osteomyelitis and was discharged with a 6-week course of IV daptomycin 600 mg (8 mg/kg) and ertapenem 1 g/d. At discharge, the patient was in stable condition. Follow-up was done by our outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) team, which consists of an infectious disease pharmacist and the physician director of antimicrobial stewardship who monitor veterans receiving outpatient IV antibiotic therapy.1

Three weeks later as part of the regular OPAT surveillance, the patient reported via telephone that his foot osteomyelitis was stable, but he had a 101 °F fever and a new cough. He was instructed to come to the emergency department (ED) immediately. On arrival,

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

In the ED, the patient was given a provisional diagnosis of multifocal bacterial pneumonia and was admitted to the hospital for further management. His outpatient regimen of IV daptomycin and ertapenem was adjusted to IV vancomycin and meropenem. The infectious disease service was consulted within 24 hours of admission, and based on the new onset chest infiltrates, therapy with daptomycin and notable peripheral blood eosinophilia, a presumptive diagnosis of daptomycin-related acute eosinophilic pneumonia was made. A medication list review yielded no other potential etiologic agents for drug-related eosinophilia, and the patient did not have any remote or recent pertinent travel history concerning for parasitic disease.

The patient was treated with oral prednisone 40 mg (0.5 mg/kg) daily and the daptomycin was not restarted. Within 24 hours, the patient’s fevers, oxygen requirements, and cough subsided. Laboratory values

Discussion

Daptomycin is a commonly used cyclic lipopeptide IV antibiotic with broad activity against gram-positive organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). Daptomycin has emerged as a convenient alternative for infections typically treated with IV vancomycin: shorter infusion time (2-30 minutes vs 60-180 minutes), daily administration, and less need for dose adjustments. A recent survey reported higher satisfaction and less disruption in patients receiving daptomycin compared with vancomycin.2 The main daptomycin-specific adverse effect (AE) that warrants close monitoring is elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels and skeletal muscle breakdown (reversible after holding medication).3 Other rarely reported AEs include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), acute eosinophilic pneumonitis, hepatitis, and peripheral neuropathy.4-6 Consequently, weekly monitoring for this drug should include symptom inquiry for cough and muscle pain, and laboratory testing with CBC with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and CK.

Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia has been described in several case reports and in a recent study, the frequency of this event was almost 5% in those receiving long-term daptomycin therapy.7 The most common symptoms include dyspnea, fever, infiltrates/opacities on chest imaging, and peripheral eosinophilia. It is theorized that the chemical structure of daptomycin causes immune-mediated pulmonary epithelial cell injury with eosinophils, resulting in increased peripheral eosinophilia.3 Risk factors that have been identified for daptomycin-induced eosinophilia include age > 70 years; the presence of comorbidities of heart and pulmonary disease; duration of daptomycin beyond 2 weeks; and cumulative doses over 10 g. Average onset of illness from initiation of daptomycin has been reported to be about 3 weeks.7,8 The diagnosis of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonitis is made on several criteria per the FDA. These include exposure to daptomycin, fever, dyspnea with oxygen requirement, new infiltrates on imaging, bronchoalveolar lavage with > 25% eosinophils, and last, clinical improvement on removal of the drug.9 However, as bronchoscopy is an invasive diagnostic modality, it is not always performed or necessary as seen in this case. Furthermore, not all patients will have peripheral eosinophilia, with only 77% of patients having that finding in a systematic review.10 Taken together, the overall true incidence of daptomycin-induced eosinophilia may be underestimated. Treatment involves discontinuation of the daptomycin and initiation of steroids. In a review of 35 cases, the majority did receive systemic steroids, usually 60 to 125 mg of IV methylprednisolone every 6 hours, which was converted to oral steroids and tapered over 2 to 6 weeks.10 However, all patients including those who did not receive steroids had symptom improvement or complete resolution, highlighting that prompt discontinuation of daptomycin is the most crucial intervention.

Conclusions

As home IV antibiotic therapy becomes increasingly used to facilitate shorter lengths of stay in hospitals and enable more patients to receive their infectious disease care at home, the general practitioner must be aware of the potential AEs of commonly used IV antibiotics. While acute cutaneous reactions and disturbances in renal and liver function are commonly recognized entities of adverse drug reactions, symptoms of fever and cough are more likely to be interpreted as acute viral or bacterial respiratory infections. A high index of clinical suspicion is needed for eosinophilic pneumonitis secondary to daptomycin. A simple and readily available test, such as a CBC with differential may facilitate the identification of this potentially serious AE, allowing prompt discontinuation of the drug.

A 70-year-old veteran with a history notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, complicated by peripheral neuropathy and bilateral foot ulceration, and previous pulmonary tuberculosis (treated in June 2013) presented to an outside medical facility with bilateral worsening foot pain, swelling, and drainage of preexisting ulcers. He received a diagnosis of bilateral fifth toe osteomyelitis and was discharged with a 6-week course of IV daptomycin 600 mg (8 mg/kg) and ertapenem 1 g/d. At discharge, the patient was in stable condition. Follow-up was done by our outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) team, which consists of an infectious disease pharmacist and the physician director of antimicrobial stewardship who monitor veterans receiving outpatient IV antibiotic therapy.1

Three weeks later as part of the regular OPAT surveillance, the patient reported via telephone that his foot osteomyelitis was stable, but he had a 101 °F fever and a new cough. He was instructed to come to the emergency department (ED) immediately. On arrival,

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

In the ED, the patient was given a provisional diagnosis of multifocal bacterial pneumonia and was admitted to the hospital for further management. His outpatient regimen of IV daptomycin and ertapenem was adjusted to IV vancomycin and meropenem. The infectious disease service was consulted within 24 hours of admission, and based on the new onset chest infiltrates, therapy with daptomycin and notable peripheral blood eosinophilia, a presumptive diagnosis of daptomycin-related acute eosinophilic pneumonia was made. A medication list review yielded no other potential etiologic agents for drug-related eosinophilia, and the patient did not have any remote or recent pertinent travel history concerning for parasitic disease.

The patient was treated with oral prednisone 40 mg (0.5 mg/kg) daily and the daptomycin was not restarted. Within 24 hours, the patient’s fevers, oxygen requirements, and cough subsided. Laboratory values

Discussion

Daptomycin is a commonly used cyclic lipopeptide IV antibiotic with broad activity against gram-positive organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE). Daptomycin has emerged as a convenient alternative for infections typically treated with IV vancomycin: shorter infusion time (2-30 minutes vs 60-180 minutes), daily administration, and less need for dose adjustments. A recent survey reported higher satisfaction and less disruption in patients receiving daptomycin compared with vancomycin.2 The main daptomycin-specific adverse effect (AE) that warrants close monitoring is elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels and skeletal muscle breakdown (reversible after holding medication).3 Other rarely reported AEs include drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), acute eosinophilic pneumonitis, hepatitis, and peripheral neuropathy.4-6 Consequently, weekly monitoring for this drug should include symptom inquiry for cough and muscle pain, and laboratory testing with CBC with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and CK.

Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia has been described in several case reports and in a recent study, the frequency of this event was almost 5% in those receiving long-term daptomycin therapy.7 The most common symptoms include dyspnea, fever, infiltrates/opacities on chest imaging, and peripheral eosinophilia. It is theorized that the chemical structure of daptomycin causes immune-mediated pulmonary epithelial cell injury with eosinophils, resulting in increased peripheral eosinophilia.3 Risk factors that have been identified for daptomycin-induced eosinophilia include age > 70 years; the presence of comorbidities of heart and pulmonary disease; duration of daptomycin beyond 2 weeks; and cumulative doses over 10 g. Average onset of illness from initiation of daptomycin has been reported to be about 3 weeks.7,8 The diagnosis of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonitis is made on several criteria per the FDA. These include exposure to daptomycin, fever, dyspnea with oxygen requirement, new infiltrates on imaging, bronchoalveolar lavage with > 25% eosinophils, and last, clinical improvement on removal of the drug.9 However, as bronchoscopy is an invasive diagnostic modality, it is not always performed or necessary as seen in this case. Furthermore, not all patients will have peripheral eosinophilia, with only 77% of patients having that finding in a systematic review.10 Taken together, the overall true incidence of daptomycin-induced eosinophilia may be underestimated. Treatment involves discontinuation of the daptomycin and initiation of steroids. In a review of 35 cases, the majority did receive systemic steroids, usually 60 to 125 mg of IV methylprednisolone every 6 hours, which was converted to oral steroids and tapered over 2 to 6 weeks.10 However, all patients including those who did not receive steroids had symptom improvement or complete resolution, highlighting that prompt discontinuation of daptomycin is the most crucial intervention.

Conclusions

As home IV antibiotic therapy becomes increasingly used to facilitate shorter lengths of stay in hospitals and enable more patients to receive their infectious disease care at home, the general practitioner must be aware of the potential AEs of commonly used IV antibiotics. While acute cutaneous reactions and disturbances in renal and liver function are commonly recognized entities of adverse drug reactions, symptoms of fever and cough are more likely to be interpreted as acute viral or bacterial respiratory infections. A high index of clinical suspicion is needed for eosinophilic pneumonitis secondary to daptomycin. A simple and readily available test, such as a CBC with differential may facilitate the identification of this potentially serious AE, allowing prompt discontinuation of the drug.

1. Kent M, Kouma M, Jodlowski T, Cutrell JB. 755. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy program evaluation within a large Veterans Affairs healthcare system. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(suppl 2):S337. Published 2019 Oct 23. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz360.823

2. Wu KH, Sakoulas G, Geriak M. Vancomycin or daptomycin for outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy: does it make a difference in patient satisfaction? Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(8):ofab418. Published 2021 Aug 30. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab418

3. Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Seaton RA, Hamed K. Daptomycin: an evidence-based review of its role in the treatment of gram-positive infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2016;9:47-58. Published 2016 Apr 15. doi:10.2147/IDR.S99046

4. Sharifzadeh S, Mohammadpour AH, Tavanaee A, Elyasi S. Antibacterial antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: a literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77(3):275-289. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-03005-9

5. Mo Y, Nehring F, Jung AH, Housman ST. Possible hepatotoxicity associated with daptomycin: a case report and literature review. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(3):253-256. doi:10.1177/0897190015625403

6. Villaverde Piñeiro L, Rabuñal Rey R, García Sabina A, Monte Secades R, García Pais MJ. Paralysis of the external popliteal sciatic nerve associated with daptomycin administration. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(4):578-580. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12666

7. Soldevila-Boixader L, Villanueva B, Ulldemolins M, et al. Risk factors of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in a population with osteoarticular infection. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(4):446. Published 2021 Apr 16. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10040446

8. Kumar S, Acosta-Sanchez I, Rajagopalan N. Daptomycin-induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2899. Published 2018 Jun 30. doi:10.7759/cureus.2899

9. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Eosinophilic pneumonia associated with the use of cubicin. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 3, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fda-drug-safety-communication-eosinophilic-pneumonia-associated-use-cubicin-daptomycin

10. Uppal P, LaPlante KL, Gaitanis MM, Jankowich MD, Ward KE. Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia—a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:55. Published 2016 Dec 12. doi:10.1186/s13756-016-0158-8

1. Kent M, Kouma M, Jodlowski T, Cutrell JB. 755. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy program evaluation within a large Veterans Affairs healthcare system. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(suppl 2):S337. Published 2019 Oct 23. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz360.823

2. Wu KH, Sakoulas G, Geriak M. Vancomycin or daptomycin for outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy: does it make a difference in patient satisfaction? Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(8):ofab418. Published 2021 Aug 30. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab418

3. Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Seaton RA, Hamed K. Daptomycin: an evidence-based review of its role in the treatment of gram-positive infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2016;9:47-58. Published 2016 Apr 15. doi:10.2147/IDR.S99046

4. Sharifzadeh S, Mohammadpour AH, Tavanaee A, Elyasi S. Antibacterial antibiotic-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: a literature review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77(3):275-289. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-03005-9

5. Mo Y, Nehring F, Jung AH, Housman ST. Possible hepatotoxicity associated with daptomycin: a case report and literature review. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(3):253-256. doi:10.1177/0897190015625403

6. Villaverde Piñeiro L, Rabuñal Rey R, García Sabina A, Monte Secades R, García Pais MJ. Paralysis of the external popliteal sciatic nerve associated with daptomycin administration. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;43(4):578-580. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12666

7. Soldevila-Boixader L, Villanueva B, Ulldemolins M, et al. Risk factors of daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia in a population with osteoarticular infection. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(4):446. Published 2021 Apr 16. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10040446

8. Kumar S, Acosta-Sanchez I, Rajagopalan N. Daptomycin-induced acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2899. Published 2018 Jun 30. doi:10.7759/cureus.2899

9. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Eosinophilic pneumonia associated with the use of cubicin. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Updated August 3, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/fda-drug-safety-communication-eosinophilic-pneumonia-associated-use-cubicin-daptomycin

10. Uppal P, LaPlante KL, Gaitanis MM, Jankowich MD, Ward KE. Daptomycin-induced eosinophilic pneumonia—a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2016;5:55. Published 2016 Dec 12. doi:10.1186/s13756-016-0158-8

Medicaid coverage of HPV vaccine in adults: Implications in dermatology

, according to the authors of a review of Medicaid policies across all 50 states.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is approved for people aged 9-45 years, for preventing genital, cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers, and genital warts. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routine vaccination with the HPV vaccine for individuals aged 9-26 years, with “shared clinical decision-making” recommended for vaccination of those aged 27-45 years, wrote Nathaniel Goldman of New York Medical College, Valhalla, and coauthors, from the University of Missouri–Kansas City and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A total of 33 states offered formal statewide Medicaid coverage policies that were accessible online or through the state’s Medicaid office. Another 11 states provided coverage through Medicaid managed care organizations, and 4 states had HPV vaccination as part of their formal Medicaid adult vaccination programs.

Overall, 43 states covered HPV vaccination through age 45 years with no need for prior authorization, and another 4 states (Ohio, Maine, Nebraska, and New York) provided coverage with prior authorization for adults older than 26 years.

The study findings were limited by the use of Medicaid coverage only, the researchers noted. Consequently, patients eligible for HPV vaccination who are uninsured or have other types of insurance may face additional barriers in the form of high costs, given that the current retail price is $250-$350 per shot for the three-shot series, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that Medicaid coverage for HPV vaccination may inform dermatologists’ recommendations for patients at increased risk, they said. More research is needed to “better identify dermatology patients at risk for new HPV infection and ways to improve vaccination rates in these vulnerable individuals,” they added.

Vaccine discussions are important in dermatology

“Dermatologists care for patients who may be an increased risk of vaccine-preventable illnesses, either from a skin disease or a dermatology medication,” corresponding author Megan H. Noe, MD, a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and assistant professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “Over the last several years, we have seen that all physicians, whether they provide vaccinations or not, can play an important role in discussing vaccines with their patients,” she said.

“Vaccines can be cost-prohibitive for patients without insurance coverage, so we hope that dermatologists will be more likely to recommend the HPV vaccine to patients 27-45 years of age if they know that it is likely covered by insurance,” Dr. Noe noted.

However, “time may be a barrier for many dermatologists who have many important things to discuss with patients during their appointments,” she said. “We are currently working on developing educational information to help facilitate this conversation,” she added.

Looking ahead, she said that “additional research is necessary to create vaccine guidelines specific to dermatology patients and dermatology medications, so we can provide clear recommendations to our patients and ensure appropriate insurance coverage for all necessary vaccines.”

Vaccine discussions

“I think it’s great that many Medicaid plans are covering HPV vaccination,” said Karl Saardi, MD, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study. “I routinely recommend [vaccination] for patients who have viral warts, since it does lead to improvement in some cases,” Dr. Saardi, who was not involved in the current study, said in an interview. “Although we don’t have the HPV vaccines in our clinic for administration, my experience has been that patients are very open to discussing it with their primary care doctors.”

Although the upper age range continues to rise, “I think getting younger people vaccinated will also prove to be important,” said Dr. Saardi, director of the inpatient dermatology service at the George Washington University Hospital.

The point made in the current study about the importance of HPV vaccination in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa is also crucial, he added. “Since chronic skin inflammation in hidradenitis drives squamous cell carcinoma, reducing the impact of HPV on such cancers makes perfect sense.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Noe disclosed grants from Boehringer Ingelheim unrelated to the current study. Dr. Saardi had no financial conflicts to disclose.

, according to the authors of a review of Medicaid policies across all 50 states.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is approved for people aged 9-45 years, for preventing genital, cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers, and genital warts. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routine vaccination with the HPV vaccine for individuals aged 9-26 years, with “shared clinical decision-making” recommended for vaccination of those aged 27-45 years, wrote Nathaniel Goldman of New York Medical College, Valhalla, and coauthors, from the University of Missouri–Kansas City and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A total of 33 states offered formal statewide Medicaid coverage policies that were accessible online or through the state’s Medicaid office. Another 11 states provided coverage through Medicaid managed care organizations, and 4 states had HPV vaccination as part of their formal Medicaid adult vaccination programs.

Overall, 43 states covered HPV vaccination through age 45 years with no need for prior authorization, and another 4 states (Ohio, Maine, Nebraska, and New York) provided coverage with prior authorization for adults older than 26 years.

The study findings were limited by the use of Medicaid coverage only, the researchers noted. Consequently, patients eligible for HPV vaccination who are uninsured or have other types of insurance may face additional barriers in the form of high costs, given that the current retail price is $250-$350 per shot for the three-shot series, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that Medicaid coverage for HPV vaccination may inform dermatologists’ recommendations for patients at increased risk, they said. More research is needed to “better identify dermatology patients at risk for new HPV infection and ways to improve vaccination rates in these vulnerable individuals,” they added.

Vaccine discussions are important in dermatology

“Dermatologists care for patients who may be an increased risk of vaccine-preventable illnesses, either from a skin disease or a dermatology medication,” corresponding author Megan H. Noe, MD, a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and assistant professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “Over the last several years, we have seen that all physicians, whether they provide vaccinations or not, can play an important role in discussing vaccines with their patients,” she said.

“Vaccines can be cost-prohibitive for patients without insurance coverage, so we hope that dermatologists will be more likely to recommend the HPV vaccine to patients 27-45 years of age if they know that it is likely covered by insurance,” Dr. Noe noted.

However, “time may be a barrier for many dermatologists who have many important things to discuss with patients during their appointments,” she said. “We are currently working on developing educational information to help facilitate this conversation,” she added.

Looking ahead, she said that “additional research is necessary to create vaccine guidelines specific to dermatology patients and dermatology medications, so we can provide clear recommendations to our patients and ensure appropriate insurance coverage for all necessary vaccines.”

Vaccine discussions

“I think it’s great that many Medicaid plans are covering HPV vaccination,” said Karl Saardi, MD, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study. “I routinely recommend [vaccination] for patients who have viral warts, since it does lead to improvement in some cases,” Dr. Saardi, who was not involved in the current study, said in an interview. “Although we don’t have the HPV vaccines in our clinic for administration, my experience has been that patients are very open to discussing it with their primary care doctors.”

Although the upper age range continues to rise, “I think getting younger people vaccinated will also prove to be important,” said Dr. Saardi, director of the inpatient dermatology service at the George Washington University Hospital.

The point made in the current study about the importance of HPV vaccination in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa is also crucial, he added. “Since chronic skin inflammation in hidradenitis drives squamous cell carcinoma, reducing the impact of HPV on such cancers makes perfect sense.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Noe disclosed grants from Boehringer Ingelheim unrelated to the current study. Dr. Saardi had no financial conflicts to disclose.

, according to the authors of a review of Medicaid policies across all 50 states.

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is approved for people aged 9-45 years, for preventing genital, cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers, and genital warts. And the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends routine vaccination with the HPV vaccine for individuals aged 9-26 years, with “shared clinical decision-making” recommended for vaccination of those aged 27-45 years, wrote Nathaniel Goldman of New York Medical College, Valhalla, and coauthors, from the University of Missouri–Kansas City and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A total of 33 states offered formal statewide Medicaid coverage policies that were accessible online or through the state’s Medicaid office. Another 11 states provided coverage through Medicaid managed care organizations, and 4 states had HPV vaccination as part of their formal Medicaid adult vaccination programs.

Overall, 43 states covered HPV vaccination through age 45 years with no need for prior authorization, and another 4 states (Ohio, Maine, Nebraska, and New York) provided coverage with prior authorization for adults older than 26 years.

The study findings were limited by the use of Medicaid coverage only, the researchers noted. Consequently, patients eligible for HPV vaccination who are uninsured or have other types of insurance may face additional barriers in the form of high costs, given that the current retail price is $250-$350 per shot for the three-shot series, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that Medicaid coverage for HPV vaccination may inform dermatologists’ recommendations for patients at increased risk, they said. More research is needed to “better identify dermatology patients at risk for new HPV infection and ways to improve vaccination rates in these vulnerable individuals,” they added.

Vaccine discussions are important in dermatology

“Dermatologists care for patients who may be an increased risk of vaccine-preventable illnesses, either from a skin disease or a dermatology medication,” corresponding author Megan H. Noe, MD, a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and assistant professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “Over the last several years, we have seen that all physicians, whether they provide vaccinations or not, can play an important role in discussing vaccines with their patients,” she said.

“Vaccines can be cost-prohibitive for patients without insurance coverage, so we hope that dermatologists will be more likely to recommend the HPV vaccine to patients 27-45 years of age if they know that it is likely covered by insurance,” Dr. Noe noted.

However, “time may be a barrier for many dermatologists who have many important things to discuss with patients during their appointments,” she said. “We are currently working on developing educational information to help facilitate this conversation,” she added.

Looking ahead, she said that “additional research is necessary to create vaccine guidelines specific to dermatology patients and dermatology medications, so we can provide clear recommendations to our patients and ensure appropriate insurance coverage for all necessary vaccines.”

Vaccine discussions

“I think it’s great that many Medicaid plans are covering HPV vaccination,” said Karl Saardi, MD, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study. “I routinely recommend [vaccination] for patients who have viral warts, since it does lead to improvement in some cases,” Dr. Saardi, who was not involved in the current study, said in an interview. “Although we don’t have the HPV vaccines in our clinic for administration, my experience has been that patients are very open to discussing it with their primary care doctors.”

Although the upper age range continues to rise, “I think getting younger people vaccinated will also prove to be important,” said Dr. Saardi, director of the inpatient dermatology service at the George Washington University Hospital.

The point made in the current study about the importance of HPV vaccination in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa is also crucial, he added. “Since chronic skin inflammation in hidradenitis drives squamous cell carcinoma, reducing the impact of HPV on such cancers makes perfect sense.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Noe disclosed grants from Boehringer Ingelheim unrelated to the current study. Dr. Saardi had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Chronic hepatitis B infections associated with a range of liver malignancies

, shows a new study conducted in South Korea.

In this study, which was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, researchers found that long-term treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) for patients with chronic hepatitis B lowered their risk of developing extrahepatic cancer types.

In addition to lowering the risk of liver cancers, treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues, including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine, adefovir, and clevudine, lowered the risk of developing cancer of the pancreas and prostate, but increased the risk of breast cancer.

By controlling chronic hepatitis B infections (CHB), NAs have been known to reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. About half of the 700,000 people who die each year from chronic hepatitis B infections also have an intrahepatic malignancy.

But extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, in which tumors grow outside of the liver in the bile ducts, is exceedingly rare, affecting only 8,000 people each year in the United States.

The study was led by Jeong-Hoon Lee, MD, PhD, Seoul National University, South Korea.

The study details

Researchers sought to understand whether CHB treatment with NA drugs could reduce the risk of extrahepatic cancer. The study is based on an analysis of South Korean medical insurance claims data that included 90,944 patients (6,539 treated with NAs) with a newly diagnosed chronic hepatitis B infection, and 685,436 controls. The median age of the groups ranged from 47 to 51, and the percentage of men ranged from 51.3% to 62.5%.

Over the median 47.4-month study period, 3.9% (30,413) of subjects developed cancer outside the liver. Patients with CHB who weren’t treated with NAs had a higher overall risk vs. the NA-treatment group (adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio = 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.45; P < .001) and vs. controls (aSHR = 1.22; 95% CI, 1.18-1.26; P < .001).

The researchers write that “the direction of the original result was maintained” even after adjustment for cancer risk factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption. “Randomized controlled trials might be warranted to explore whether NA treatment will reduce the risk of extrahepatic malignancy in patients with CHB outside the current treatment indication,” they wrote.

In an accompanying commentary, Lewis R. Roberts, MBChB, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that what is perhaps “the most controversial result ... one that is not the direct subject of their study, the observation that NA treatment was not associated with a decrease in risk of primary intrahepatic malignancy – hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The observed decrease in risk of intrahepatic malignancy was 12%, with an adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.77-1.01; P = .08).”

As Dr. Roberts wrote, the authors suggested this could be related to the low prevalence of cirrhosis in the study group. “This explanation is plausible, as it has previously been shown that the major impact of NA treatment in reducing HCC incidence is in those with CHB-induced cirrhosis,” he wrote.

Dr. Roberts added that randomized trials of NA in CHB would be difficult because the drugs are so effective. “The most important implication of this study may be the observation that CHB is associated with a higher risk of a range of extrahepatic malignancies, and the opportunity to advise patients with CHB to adhere to current recommendations for screening for the major cancer types.”

The study was publicly funded, but several study authors report numerous disclosures including relationships with Yuhan Corporation, Bayer, Gilead Sciences, Bristol Myers Squibb, and others. Dr. Roberts reports numerous personal and institutional disclosures including relationships with Bayer, Gilead Sciences, Medscape, Roche, and others plus a patent and royalties.

, shows a new study conducted in South Korea.

In this study, which was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, researchers found that long-term treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs) for patients with chronic hepatitis B lowered their risk of developing extrahepatic cancer types.

In addition to lowering the risk of liver cancers, treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues, including tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, entecavir, lamivudine, telbivudine, adefovir, and clevudine, lowered the risk of developing cancer of the pancreas and prostate, but increased the risk of breast cancer.

By controlling chronic hepatitis B infections (CHB), NAs have been known to reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. About half of the 700,000 people who die each year from chronic hepatitis B infections also have an intrahepatic malignancy.

But extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, in which tumors grow outside of the liver in the bile ducts, is exceedingly rare, affecting only 8,000 people each year in the United States.

The study was led by Jeong-Hoon Lee, MD, PhD, Seoul National University, South Korea.

The study details

Researchers sought to understand whether CHB treatment with NA drugs could reduce the risk of extrahepatic cancer. The study is based on an analysis of South Korean medical insurance claims data that included 90,944 patients (6,539 treated with NAs) with a newly diagnosed chronic hepatitis B infection, and 685,436 controls. The median age of the groups ranged from 47 to 51, and the percentage of men ranged from 51.3% to 62.5%.

Over the median 47.4-month study period, 3.9% (30,413) of subjects developed cancer outside the liver. Patients with CHB who weren’t treated with NAs had a higher overall risk vs. the NA-treatment group (adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio = 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.12-1.45; P < .001) and vs. controls (aSHR = 1.22; 95% CI, 1.18-1.26; P < .001).

The researchers write that “the direction of the original result was maintained” even after adjustment for cancer risk factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption. “Randomized controlled trials might be warranted to explore whether NA treatment will reduce the risk of extrahepatic malignancy in patients with CHB outside the current treatment indication,” they wrote.

In an accompanying commentary, Lewis R. Roberts, MBChB, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that what is perhaps “the most controversial result ... one that is not the direct subject of their study, the observation that NA treatment was not associated with a decrease in risk of primary intrahepatic malignancy – hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The observed decrease in risk of intrahepatic malignancy was 12%, with an adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.77-1.01; P = .08).”

As Dr. Roberts wrote, the authors suggested this could be related to the low prevalence of cirrhosis in the study group. “This explanation is plausible, as it has previously been shown that the major impact of NA treatment in reducing HCC incidence is in those with CHB-induced cirrhosis,” he wrote.

Dr. Roberts added that randomized trials of NA in CHB would be difficult because the drugs are so effective. “The most important implication of this study may be the observation that CHB is associated with a higher risk of a range of extrahepatic malignancies, and the opportunity to advise patients with CHB to adhere to current recommendations for screening for the major cancer types.”