User login

Pro-life ob.gyns. say Dobbs not end of abortion struggle

After 49 years of labor, abortion foes received the ultimate victory in June when the United States Supreme Court struck down a federal right to terminate pregnancy. Among those most heartened by the ruling was a small organization of doctors who specialize in women’s reproductive health. The group’s leader, while grateful for the win, isn’t ready for a curtain call. Instead, she sees her task as moving from a national stage to 50 regional ones.

The decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned a woman’s constitutional right to obtain an abortion, was the biggest but not final quarry for the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG). “It actually doesn’t change anything except to turn the whole discussion on abortion back to the states, which in our opinion is where it should have been 50 years ago,” Donna Harrison, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, said in a recent interview.

Dr. Harrison, an obstetrician-gynecologist and adjunct professor of bioethics at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Ind., said she was proud of “our small role in bringing science” to the top court’s attention, noting that the ruling incorporated some of AAPLOG’s medical arguments in reversing Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that created a right to abortion – and prompted her group’s founding. The ruling, for instance, agreed – in a departure from the generally accepted science – that a fetus is viable at 15 weeks, and the procedure is risky for mothers thereafter. “You could congratulate us for perseverance and for bringing that information, which has been in the peer-reviewed literature for a long time, to the justices’ attention,” she said.

Dr. Harrison said she was pleased that the Supreme Court agreed with the “science” that guided its decision to overturn Roe. That the court was willing to embrace that evidence troubles the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the nation’s leading professional group for reproductive health experts.

Defending the ‘second patient’

AAPLOG operates under the belief that life begins at the moment of fertilization, at which point “we defend the life of our second patient, the human being in the womb,” Dr. Harrison said. “For a very long time, ob.gyns. who valued both patients were not given a voice, and I think now we’re finding our voice.” The group will continue supporting abortion restrictions at the state level.

AAPLOG, with 6,000 members, was considered a “special interest” group within ACOG until the college discontinued such subgroups in 2013. ACOG, numbering 60,000 members, calls the Dobbs ruling “a huge step back for women and everyone who is seeking access to ob.gyn. care,” said Molly Meegan, JD, ACOG’s chief legal officer. Ms. Meegan expressed concern over the newfound influence of AAPLOG, which she called “a single-issue, single-topic, single-advocacy organization.”

Pro-choice groups, including ACOG, worry that the reversal of Roe has provided AAPLOG with an undeserved veneer of medical expertise. The decision also allowed judges and legislators to “insert themselves into nuanced and complex situations” they know little about and will rely on groups like AAPLOG to exert influence, Ms. Meegan said.

In turn, Dr. Harrison described ACOG as engaging in “rabid, pro-abortion activism.”

The number of abortions in the United States had steadily declined from a peak of 1.4 million per year in 1990 until 2017, after which it has risen slightly. In 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 625,000 abortions occurred nationally. Of those, 42.3% were medication abortions performed in the first 9 weeks, using a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol. Medication abortions now account for more than half of all pregnancy terminations in the United States, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Dr. Harrison said that medication abortions put women at an elevated risk of serious, sometimes deadly bleeding, while ACOG points to evidence that the risk of childbirth to women is significantly higher. She also is no fan of Plan B, the “morning after” pill, which is available to women without having to consult a doctor. She described abortifacients as “a huge danger to women being harmed” by medications available over the counter.

In Dr. Harrison’s view, the 10-year-old Ohio girl who traveled to Indiana to obtain an abortion after she became pregnant as the result of rape should have continued her pregnancy. So, too, should young girls who are the victims of incest. “Incest is a horrific crime,” she said, “but aborting a girl because of incest doesn’t make her un-raped. It just adds another trauma.”

When told of Dr. Harrison’s comment, Ms. Meegan paused for 5 seconds before saying, “I think that statement speaks for itself.”

Louise Perkins King, MD, JD, an ob.gyn. and director of reproductive bioethics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said she had the “horrific” experience of delivering a baby to an 11-year-old girl.

“Children are not fully developed, and they should not be having children,” Dr. King said.

Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, vice chair of ACOG’s Clinical Consensus Committee and an ob.gyn. at Seattle Children’s in Washington, said in a statement that adolescents who are sexually assaulted are at extremely high risk of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. “Do we expect a fourth-grader to carry a pregnancy to term, deliver, and expect that child to carry on after this horror?,” she asked.

Dr. Harrison dismissed such concerns. “Somehow abortion is a mental health treatment? Abortion doesn’t treat mental health problems,” she said. “Is there any proof that aborting in those circumstances improves their mental health? I would tell you there is very little research about it. …There are human beings involved, and this child who was raped, who also had a child, who was a human being, who is no longer.”

Dr. Harrison said the Dobbs decision would have no effect on up to 93% of ob.gyns. who don’t perform abortions. Dr. King said the reason that most don’t perform the procedure is the “stigma” attached to abortion. “It’s still frowned upon,” she said. “We don’t talk about it as health care.”

Ms. Meegan added that ob.gyns. are fearful in the wake of the Dobbs decision because “they might find themselves subject to civil and criminal penalties.”

Dr. Harrison said that Roe was always a political decision and the science was always behind AAPLOG – something both Ms. Meegan and Dr. King dispute. Ms. Meegan and Dr. King said they are concerned about the chilling effects on both women and their clinicians, especially with laws that prevent referrals and travel to other states.

“You can’t compel me to give blood or bone marrow,” Dr. King said. “You can’t even compel me to give my hair for somebody, and you can’t compel me to give an organ. And all of a sudden when I’m pregnant, all my rights are out the window?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 49 years of labor, abortion foes received the ultimate victory in June when the United States Supreme Court struck down a federal right to terminate pregnancy. Among those most heartened by the ruling was a small organization of doctors who specialize in women’s reproductive health. The group’s leader, while grateful for the win, isn’t ready for a curtain call. Instead, she sees her task as moving from a national stage to 50 regional ones.

The decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned a woman’s constitutional right to obtain an abortion, was the biggest but not final quarry for the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG). “It actually doesn’t change anything except to turn the whole discussion on abortion back to the states, which in our opinion is where it should have been 50 years ago,” Donna Harrison, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, said in a recent interview.

Dr. Harrison, an obstetrician-gynecologist and adjunct professor of bioethics at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Ind., said she was proud of “our small role in bringing science” to the top court’s attention, noting that the ruling incorporated some of AAPLOG’s medical arguments in reversing Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that created a right to abortion – and prompted her group’s founding. The ruling, for instance, agreed – in a departure from the generally accepted science – that a fetus is viable at 15 weeks, and the procedure is risky for mothers thereafter. “You could congratulate us for perseverance and for bringing that information, which has been in the peer-reviewed literature for a long time, to the justices’ attention,” she said.

Dr. Harrison said she was pleased that the Supreme Court agreed with the “science” that guided its decision to overturn Roe. That the court was willing to embrace that evidence troubles the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the nation’s leading professional group for reproductive health experts.

Defending the ‘second patient’

AAPLOG operates under the belief that life begins at the moment of fertilization, at which point “we defend the life of our second patient, the human being in the womb,” Dr. Harrison said. “For a very long time, ob.gyns. who valued both patients were not given a voice, and I think now we’re finding our voice.” The group will continue supporting abortion restrictions at the state level.

AAPLOG, with 6,000 members, was considered a “special interest” group within ACOG until the college discontinued such subgroups in 2013. ACOG, numbering 60,000 members, calls the Dobbs ruling “a huge step back for women and everyone who is seeking access to ob.gyn. care,” said Molly Meegan, JD, ACOG’s chief legal officer. Ms. Meegan expressed concern over the newfound influence of AAPLOG, which she called “a single-issue, single-topic, single-advocacy organization.”

Pro-choice groups, including ACOG, worry that the reversal of Roe has provided AAPLOG with an undeserved veneer of medical expertise. The decision also allowed judges and legislators to “insert themselves into nuanced and complex situations” they know little about and will rely on groups like AAPLOG to exert influence, Ms. Meegan said.

In turn, Dr. Harrison described ACOG as engaging in “rabid, pro-abortion activism.”

The number of abortions in the United States had steadily declined from a peak of 1.4 million per year in 1990 until 2017, after which it has risen slightly. In 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 625,000 abortions occurred nationally. Of those, 42.3% were medication abortions performed in the first 9 weeks, using a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol. Medication abortions now account for more than half of all pregnancy terminations in the United States, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Dr. Harrison said that medication abortions put women at an elevated risk of serious, sometimes deadly bleeding, while ACOG points to evidence that the risk of childbirth to women is significantly higher. She also is no fan of Plan B, the “morning after” pill, which is available to women without having to consult a doctor. She described abortifacients as “a huge danger to women being harmed” by medications available over the counter.

In Dr. Harrison’s view, the 10-year-old Ohio girl who traveled to Indiana to obtain an abortion after she became pregnant as the result of rape should have continued her pregnancy. So, too, should young girls who are the victims of incest. “Incest is a horrific crime,” she said, “but aborting a girl because of incest doesn’t make her un-raped. It just adds another trauma.”

When told of Dr. Harrison’s comment, Ms. Meegan paused for 5 seconds before saying, “I think that statement speaks for itself.”

Louise Perkins King, MD, JD, an ob.gyn. and director of reproductive bioethics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said she had the “horrific” experience of delivering a baby to an 11-year-old girl.

“Children are not fully developed, and they should not be having children,” Dr. King said.

Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, vice chair of ACOG’s Clinical Consensus Committee and an ob.gyn. at Seattle Children’s in Washington, said in a statement that adolescents who are sexually assaulted are at extremely high risk of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. “Do we expect a fourth-grader to carry a pregnancy to term, deliver, and expect that child to carry on after this horror?,” she asked.

Dr. Harrison dismissed such concerns. “Somehow abortion is a mental health treatment? Abortion doesn’t treat mental health problems,” she said. “Is there any proof that aborting in those circumstances improves their mental health? I would tell you there is very little research about it. …There are human beings involved, and this child who was raped, who also had a child, who was a human being, who is no longer.”

Dr. Harrison said the Dobbs decision would have no effect on up to 93% of ob.gyns. who don’t perform abortions. Dr. King said the reason that most don’t perform the procedure is the “stigma” attached to abortion. “It’s still frowned upon,” she said. “We don’t talk about it as health care.”

Ms. Meegan added that ob.gyns. are fearful in the wake of the Dobbs decision because “they might find themselves subject to civil and criminal penalties.”

Dr. Harrison said that Roe was always a political decision and the science was always behind AAPLOG – something both Ms. Meegan and Dr. King dispute. Ms. Meegan and Dr. King said they are concerned about the chilling effects on both women and their clinicians, especially with laws that prevent referrals and travel to other states.

“You can’t compel me to give blood or bone marrow,” Dr. King said. “You can’t even compel me to give my hair for somebody, and you can’t compel me to give an organ. And all of a sudden when I’m pregnant, all my rights are out the window?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

After 49 years of labor, abortion foes received the ultimate victory in June when the United States Supreme Court struck down a federal right to terminate pregnancy. Among those most heartened by the ruling was a small organization of doctors who specialize in women’s reproductive health. The group’s leader, while grateful for the win, isn’t ready for a curtain call. Instead, she sees her task as moving from a national stage to 50 regional ones.

The decision in Dobbs v. Jackson, which overturned a woman’s constitutional right to obtain an abortion, was the biggest but not final quarry for the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG). “It actually doesn’t change anything except to turn the whole discussion on abortion back to the states, which in our opinion is where it should have been 50 years ago,” Donna Harrison, MD, the group’s chief executive officer, said in a recent interview.

Dr. Harrison, an obstetrician-gynecologist and adjunct professor of bioethics at Trinity International University in Deerfield, Ind., said she was proud of “our small role in bringing science” to the top court’s attention, noting that the ruling incorporated some of AAPLOG’s medical arguments in reversing Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that created a right to abortion – and prompted her group’s founding. The ruling, for instance, agreed – in a departure from the generally accepted science – that a fetus is viable at 15 weeks, and the procedure is risky for mothers thereafter. “You could congratulate us for perseverance and for bringing that information, which has been in the peer-reviewed literature for a long time, to the justices’ attention,” she said.

Dr. Harrison said she was pleased that the Supreme Court agreed with the “science” that guided its decision to overturn Roe. That the court was willing to embrace that evidence troubles the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the nation’s leading professional group for reproductive health experts.

Defending the ‘second patient’

AAPLOG operates under the belief that life begins at the moment of fertilization, at which point “we defend the life of our second patient, the human being in the womb,” Dr. Harrison said. “For a very long time, ob.gyns. who valued both patients were not given a voice, and I think now we’re finding our voice.” The group will continue supporting abortion restrictions at the state level.

AAPLOG, with 6,000 members, was considered a “special interest” group within ACOG until the college discontinued such subgroups in 2013. ACOG, numbering 60,000 members, calls the Dobbs ruling “a huge step back for women and everyone who is seeking access to ob.gyn. care,” said Molly Meegan, JD, ACOG’s chief legal officer. Ms. Meegan expressed concern over the newfound influence of AAPLOG, which she called “a single-issue, single-topic, single-advocacy organization.”

Pro-choice groups, including ACOG, worry that the reversal of Roe has provided AAPLOG with an undeserved veneer of medical expertise. The decision also allowed judges and legislators to “insert themselves into nuanced and complex situations” they know little about and will rely on groups like AAPLOG to exert influence, Ms. Meegan said.

In turn, Dr. Harrison described ACOG as engaging in “rabid, pro-abortion activism.”

The number of abortions in the United States had steadily declined from a peak of 1.4 million per year in 1990 until 2017, after which it has risen slightly. In 2019, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 625,000 abortions occurred nationally. Of those, 42.3% were medication abortions performed in the first 9 weeks, using a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol. Medication abortions now account for more than half of all pregnancy terminations in the United States, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Dr. Harrison said that medication abortions put women at an elevated risk of serious, sometimes deadly bleeding, while ACOG points to evidence that the risk of childbirth to women is significantly higher. She also is no fan of Plan B, the “morning after” pill, which is available to women without having to consult a doctor. She described abortifacients as “a huge danger to women being harmed” by medications available over the counter.

In Dr. Harrison’s view, the 10-year-old Ohio girl who traveled to Indiana to obtain an abortion after she became pregnant as the result of rape should have continued her pregnancy. So, too, should young girls who are the victims of incest. “Incest is a horrific crime,” she said, “but aborting a girl because of incest doesn’t make her un-raped. It just adds another trauma.”

When told of Dr. Harrison’s comment, Ms. Meegan paused for 5 seconds before saying, “I think that statement speaks for itself.”

Louise Perkins King, MD, JD, an ob.gyn. and director of reproductive bioethics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said she had the “horrific” experience of delivering a baby to an 11-year-old girl.

“Children are not fully developed, and they should not be having children,” Dr. King said.

Anne-Marie E. Amies Oelschlager, MD, vice chair of ACOG’s Clinical Consensus Committee and an ob.gyn. at Seattle Children’s in Washington, said in a statement that adolescents who are sexually assaulted are at extremely high risk of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. “Do we expect a fourth-grader to carry a pregnancy to term, deliver, and expect that child to carry on after this horror?,” she asked.

Dr. Harrison dismissed such concerns. “Somehow abortion is a mental health treatment? Abortion doesn’t treat mental health problems,” she said. “Is there any proof that aborting in those circumstances improves their mental health? I would tell you there is very little research about it. …There are human beings involved, and this child who was raped, who also had a child, who was a human being, who is no longer.”

Dr. Harrison said the Dobbs decision would have no effect on up to 93% of ob.gyns. who don’t perform abortions. Dr. King said the reason that most don’t perform the procedure is the “stigma” attached to abortion. “It’s still frowned upon,” she said. “We don’t talk about it as health care.”

Ms. Meegan added that ob.gyns. are fearful in the wake of the Dobbs decision because “they might find themselves subject to civil and criminal penalties.”

Dr. Harrison said that Roe was always a political decision and the science was always behind AAPLOG – something both Ms. Meegan and Dr. King dispute. Ms. Meegan and Dr. King said they are concerned about the chilling effects on both women and their clinicians, especially with laws that prevent referrals and travel to other states.

“You can’t compel me to give blood or bone marrow,” Dr. King said. “You can’t even compel me to give my hair for somebody, and you can’t compel me to give an organ. And all of a sudden when I’m pregnant, all my rights are out the window?”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2022: Sleep Disorders

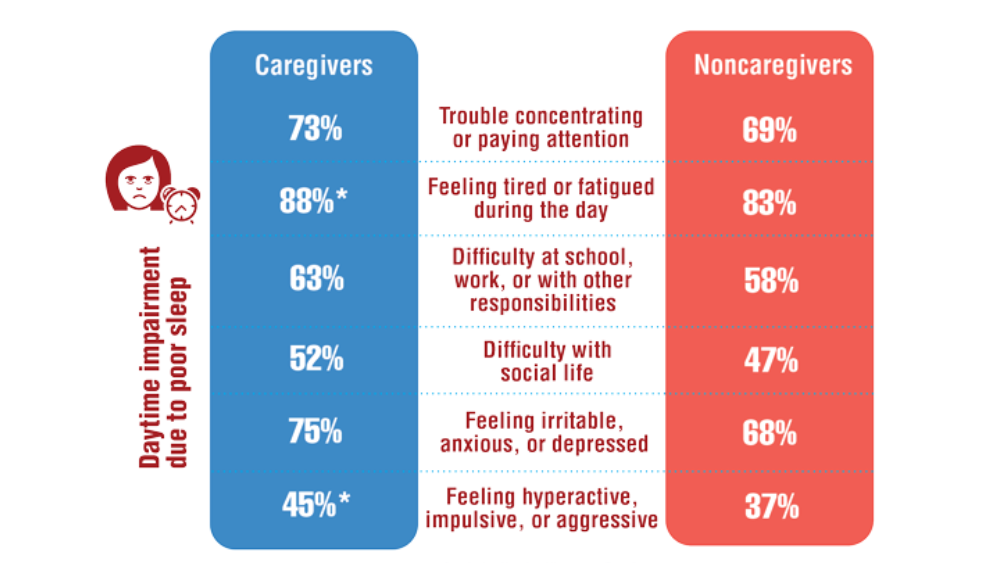

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

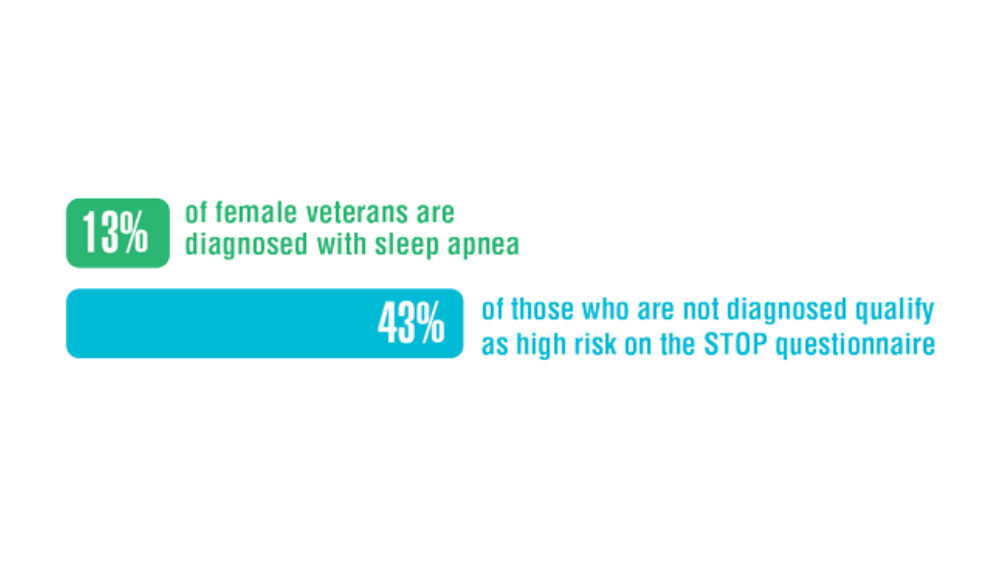

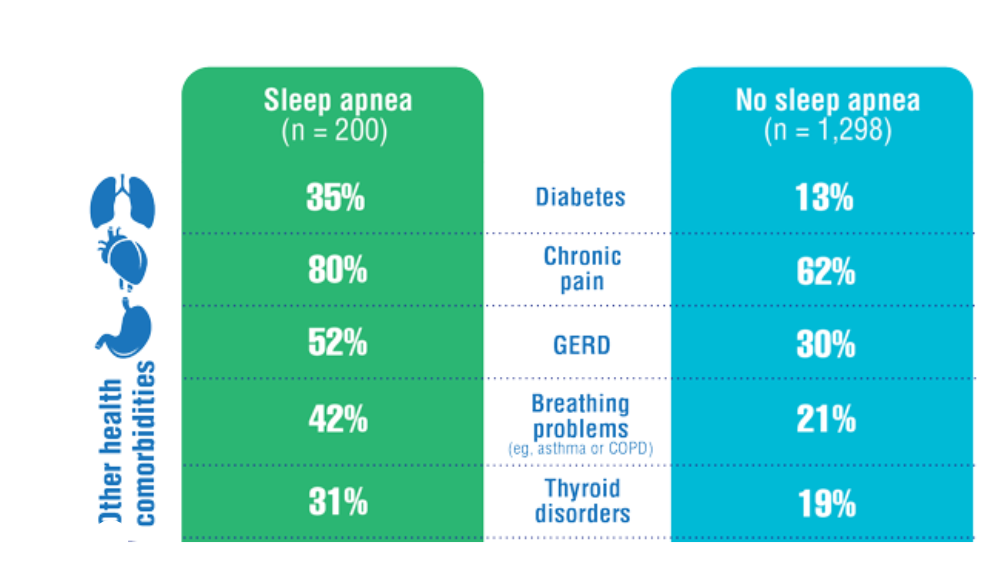

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

- Song Y, Carlson GC, McGowan SK, et al. Sleep disruption due to stress in women veterans: a comparison between caregivers and noncaregivers. Behav Sleep Med. 2021;19(2):243-254. http://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2020.1732981

- Martin JL, Carlson G, Kelly M, et al. Sleep apnea in women veterans: results of a national survey of VA health care users. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):555-565. http://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8956

Impact of Race on Outcomes of High-Risk Patients With Prostate Cancer Treated With Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy in an Equal Access Setting

Although moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHRT) is an accepted treatment for localized prostate cancer, its adaptation remains limited in the United States.1,2 MHRT theoretically exploits α/β ratio differences between the prostate (1.5 Gy), bladder (5-10 Gy), and rectum (3 Gy), thereby reducing late treatment-related adverse effects compared with those of conventional fractionation at biologically equivalent doses.3-8 Multiple randomized noninferiority trials have demonstrated equivalent outcomes between MHRT and conventional fraction with no appreciable increase in patient-reported toxicity.9-14 Although these studies have led to the acceptance of MHRT as a standard treatment, the majority of these trials involve individuals with low- and intermediate-risk disease.

There are less phase 3 data addressing MHRT for high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).10,12,14-17 Only 2 studies examined predominately high-risk populations, accounting for 83 and 292 patients, respectively.15,16 Additional phase 3 trials with small proportions of high-risk patients (n = 126, 12%; n = 53, 35%) offer limited additional information regarding clinical outcomes and toxicity rates specific to high-risk disease.10-12 Numerous phase 1 and 2 studies report various field designs and fractionation plans for MHRT in the context of high-risk disease, although the applicability of these data to off-trial populations remains limited.18-20

Furthermore, African American individuals are underrepresented in the trials establishing the role of MHRT despite higher rates of prostate cancer incidence, more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and higher rates of prostate cancer–specific survival (PCSS) when compared with White patients.21 Racial disparities across patients with prostate cancer and their management are multifactorial across health care literacy, education level, access to care (including transportation issues), and issues of adherence and distrust.22-25 Correlation of patient race to prostate cancer outcomes varies greatly across health care systems, with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) equal access system providing robust mental health services and transportation services for some patients, while demonstrating similar rates of stage-adjusted PCSS between African American and White patients across a broad range of treatment modalities.26-28 Given the paucity of data exploring outcomes following MHRT for African American patients with HRPC, the present analysis provides long-term clinical outcomes and toxicity profiles for an off-trial majority African American population with HRPC treated with MHRT within the VA.

Methods

Records were retrospectively reviewed under an institutional review board–approved protocol for all patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT at the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in North Carolina between November 2008 and August 2018. Exclusion criteria included < 12 months of follow-up or elective nodal irradiation. Demographic variables obtained included age at diagnosis, race, clinical T stage, pre-MHRT prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason grade group at diagnosis, favorable vs unfavorable high-risk disease, pre-MHRT international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and pre-MHRT urinary medication usage (yes/no).29

Concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was initiated 6 to 8 weeks before MHRT unless medically contraindicated per the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. Patients generally received 18 to 24 months of ADT, with those with favorable HRPC (ie, T1c disease with either Gleason 4+4 and PSA < 10 mg/mL or Gleason 3+3 and PSA > 20 ng/mL) receiving 6 months after 2015.29 Patients were simulated supine in either standard or custom immobilization with a full bladder and empty rectum. MHRT fractionation plans included 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction and 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction. Radiotherapy targets included the prostate and seminal vesicles without elective nodal coverage per institutional practice. Treatments were delivered following image guidance, either prostate matching with cone beam computed tomography or fiducial matching with kilo voltage imaging. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy. For plans delivering 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction, constraints included bladder V (volume receiving) 70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 15%, V40 ≤ 35%, rectum V70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 10%, V40 ≤ 35%, femoral heads maximum point dose ≤ 40 Gy, penile bulb mean dose ≤ 50 Gy, and small bowel V40 ≤ 1%. For plans delivering 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction, constraints included rectum V57 ≤ 15%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, bladder V60 ≤ 5%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, and femoral heads V43 ≤ 5%.

Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicities were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0, with acute toxicity defined as on-treatment < 3 months following completion of MHRT. Late toxicity was defined as ≥ 3 months following completion of MHRT. Individuals were seen in follow-up at 6 weeks and 3 months with PSA and testosterone after MHRT completion, then every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter. Each follow-up visit included history, physical examination, IPSS, and CTCAE grading for GI and GU toxicity.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test and χ2 test were used to compare differences in demographic data, dosimetric parameters, and frequency of toxicity events with respect to patient race. Clinical endpoints including biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS; defined by Phoenix criteria as 2.0 above PSA nadir), distant metastases-free survival (DMFS), PCSS, and overall survival (OS) were estimated from time of radiotherapy completion by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between African American and White race by log-rank testing.30 Late GI and GU toxicity-free survival were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots and compared between African American and White patients by the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

We identified 143 patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT between November 2008 and August 2018 (Table 1). Mean age was 65 years (range, 36-80 years); 57% were African American men. Eighty percent of individuals had unfavorable high-risk disease. Median (IQR) PSA was 14.4 (7.8-28.6). Twenty-six percent had grade group 1-3 disease, 47% had grade group 4 disease, and 27% had grade group 5 disease. African American patients had significantly lower pre-MHRT IPSS scores than White patients (mean IPSS, 11 vs 14, respectively; P = .02) despite similar rates of preradiotherapy urinary medication usage (66% and 66%, respectively).

Eighty-six percent received 70 Gy over 28 fractions, with institutional protocol shifting to 60 Gy over 20 fractions (14%) in June 2017. The median (IQR) duration of radiotherapy was 39 (38-42) days, with 97% of individuals undergoing ADT for a median (IQR) duration of 24 (24-36) months. The median follow-up time was 38 months, with 57 (40%) patients followed for at least 60 months.

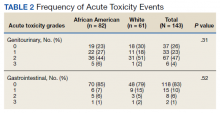

Grade 3 GI and GU acute toxicity events were observed in 1% and 4% of all individuals, respectively (Table 2). No acute GI or GU grade 4+ events were observed. No significant differences in acute GU or GI toxicity were observed between African American and White patients.

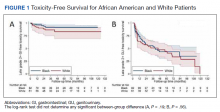

No significant differences between African American and White patients were observed for late grade 2+ GI (P = .19) or GU (P = .55) toxicity. Late grade 2+ GI toxicity was observed in 17 (12%) patients overall (Figure 1A). One grade 3 and 1 grade 4 late GI event were observed following MHRT completion: The latter involved hospitalization for bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis in the context of cirrhosis predating MHRT. Late grade 2+ GU toxicity was observed in 80 (56%) patients, with late grade 2 events steadily increasing over time (Figure 1B). Nine late grade 3 GU toxicity events were observed at a median of 13 months following completion of MHRT, 2 of which occurred more than 24 months after MHRT completion. No late grade 4 or 5 GU events were observed. IPSS values both before MHRT and at time of last follow-up were available for 65 (40%) patients, with a median (IQR) IPSS of 10 (6-16) before MHRT and 12 (8-16) at last follow-up at a median (IQR) interval of 36 months (26-76) from radiation completion.

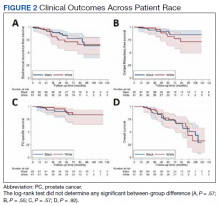

No significant differences were observed between African American and White patients with respect to BRFS, DMFS, PCSS, or OS (Figure 2). Overall, 21 of 143 (15%) patients experienced biochemical recurrence: 5-year BRFS was 77% (95% CI, 67%-85%) for all patients, 83% (95% CI, 70%-91%) for African American patients, and 71% (95% CI, 53%-82%) for White patients. Five-year DMFS was 87% (95% CI, 77%-92%) for all individuals, 91% (95% CI, 80%-96%) for African American patients, and 81% (95% CI, 62%-91%) for White patients. Five-year PCSS was 89% (95% CI, 80%-94%) for all patients, with 5-year PCSS rates of 90% (95% CI, 79%-95%) for African American patients and 87% (95% CI, 70%-95%) for White patients. Five-year OS was 75% overall (95% CI, 64%-82%), with 5-year OS rates of 73% (95% CI, 58%-83%) for African American patients and 77% (95% CI, 60%-87%) for White patients.

Discussion

In this study, we reported acute and late GI and GU toxicity rates as well as clinical outcomes for a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access health care environment. We found that MHRT was well tolerated with high rates of biochemical control, PCSS, and OS. Additionally, outcomes were not significantly different across patient race. To our knowledge, this is the first report of MHRT for HRPC in a majority African American population.

We found that MHRT was an effective treatment for patients with HRPC, in particular those with unfavorable high-risk disease. While prior prospective and randomized studies have investigated the use of MHRT, our series was larger than most and had a predominately unfavorable high-risk population.12,15-17 Our biochemical and PCSS rates compare favorably with those of HRPC trial populations, particularly given the high proportion of unfavorable high-risk disease.12,15,16 Despite similar rates of biochemical control, OS was lower in the present cohort than in HRPC trial populations, even with a younger median age at diagnosis. The similarly high rates of non–HRPC-related death across race may reflect differences in baseline comorbidities compared with trial populations as well as reported differences between individuals in the VA and the private sector.31 This suggests that MHRT can be an effective treatment for patients with unfavorable HRPC.

We did not find any differences in outcomes between African American and White individuals with HRPC treated with MHRT. Furthermore, our study demonstrates long-term rates of BRFS and PCSS in a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC that are comparable with those of prior randomized MHRT studies in high-risk, predominately White populations.12,15,16 Prior reports have found that African American men with HRPC may be at increased risk for inferior clinical outcomes due to a number of socioeconomic, biologic, and cultural mediators.26,27,32 Such individuals may disproportionally benefit from shorter treatment courses that improve access to radiotherapy, a well-documented disparity for African American men with localized prostate cancer.33-36 The VA is an ideal system for studying racial disparities within prostate cancer, as accessibility of mental health and transportation services, income, and insurance status are not barriers to preventative or acute care.37 Our results are concordant with those previously seen for African American patients with prostate cancer seen in the VA, which similarly demonstrate equal outcomes with those of other races.28,36 Incorporation of the earlier mentioned VA services into oncologic care across other health care systems could better characterize determinants of racial disparities in prostate cancer, including the prognostic significance of shortening treatment duration and number of patient visits via MHRT.

Despite widespread acceptance in prostate cancer radiotherapy guidelines, routine use of MHRT seems limited across all stages of localized prostate cancer.1,2 Late toxicity is a frequently noted concern regarding MHRT use. Higher rates of late grade 2+ GI toxicity were observed in the hypofractionation arm of the HYPRO trial.17 While RTOG 0415 did not include patients with HRPC, significantly higher rates of physician-reported (but not patient-reported) late grade 2+ GI and GU toxicity were observed using the same MHRT fractionation regimen used for the majority of individuals in our cohort.9 In our study, the steady increase in late grade 2 GU toxicity is consistent with what is seen following conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and is likely multifactorial.38 The mean IPSS difference of 2/35 from pre-MHRT baseline to the time of last follow-up suggests minimal quality of life decline. The relatively stable IPSSs over time alongside the > 50% prevalence of late grade 2 GU toxicity per CTCAE grading seems consistent with the discrepancy noted in RTOG 0415 between increased physician-reported late toxicity and favorable patient-reported quality of life scores.9 Moreover, significant variance exists in toxicity grading across scoring systems, revised editions of CTCAE, and physician-specific toxicity classification, particularly with regard to the use of adrenergic receptor blocker medications. In light of these factors, the high rate of late grade 2 GU toxicity in our study should be interpreted in the context of largely stable post-MHRT IPSSs and favorable rates of late GI grade 2+ and late GU grade 3+ toxicity.

Limitations

This study has several inherent limitations. While the size of the current HRPC cohort is notably larger than similar populations within the majority of phase 3 MHRT trials, these data derive from a single VA hospital. It is unclear whether these outcomes would be representative in a similar high-risk population receiving care outside of the VA equal access system. Follow-up data beyond 5 years was available for less than half of patients, partially due to nonprostate cancer–related mortality at a higher rate than observed in HRPC trial populations.12,15,16 Furthermore, all GI toxicity events were exclusively physician reported, and GU toxicity reporting was limited in the off-trial setting with not all patients routinely completing IPSS questionnaires following MHRT completion. However, all patients were treated similarly, and radiation quality was verified over the treatment period with mandated accreditation, frequent standardized output checks, and systematic treatment review.39

Conclusions

Patients with HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access, off-trial setting demonstrated favorable rates of biochemical control with acceptable rates of acute and late GI and GU toxicities. Clinical outcomes, including biochemical control, were not significantly different between African American and White patients, which may reflect equal access to care within the VA irrespective of income and insurance status. Incorporating VA services, such as access to primary care, mental health services, and transportation across other health care systems may aid in characterizing and mitigating racial and gender disparities in oncologic care.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were presented at the November 2020 ASTRO conference. 40

1. Stokes WA, Kavanagh BD, Raben D, Pugh TJ. Implementation of hypofractionated prostate radiation therapy in the United States: a National Cancer Database analysis. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7:270-278. doi:10.1016/j.prro.2017.03.011

2. Jaworski L, Dominello MM, Heimburger DK, et al. Contemporary practice patterns for intact and post-operative prostate cancer: results from a statewide collaborative. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(1):E282. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.06.1915

3. Miralbell R, Roberts SA, Zubizarreta E, Hendry JH. Dose-fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5,969 patients in seven international institutional datasets: α/β = 1.4 (0.9-2.2) Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):e17-e24. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.075

4. Tree AC, Khoo VS, van As NJ, Partridge M. Is biochemical relapse-free survival after profoundly hypofractionated radiotherapy consistent with current radiobiological models? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2014;26(4):216-229. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2014.01.008

5. Brenner DJ. Fractionation and late rectal toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(4):1013-1015. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.014

6. Tucker SL, Thames HD, Michalski JM, et al. Estimation of α/β for late rectal toxicity based on RTOG 94-06. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(2):600-605. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.080

7. Dasu A, Toma-Dasu I. Prostate alpha/beta revisited—an analysis of clinical results from 14 168 patients. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(8):963-974. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2012.719635 start

8. Proust-Lima C, Taylor JMG, Sécher S, et al. Confirmation of a Low α/β ratio for prostate cancer treated by external beam radiation therapy alone using a post-treatment repeated-measures model for PSA dynamics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(1):195-201. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.008

9. Lee WR, Dignam JJ, Amin MB, et al. Randomized phase III noninferiority study comparing two radiotherapy fractionation schedules in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20): 2325-2332. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.67.0448

10. Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1047-1060. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4

11. Catton CN, Lukka H, Gu C-S, et al. Randomized trial of a hypofractionated radiation regimen for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1884-1890. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7397

12. Pollack A, Walker G, Horwitz EM, et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3860-3868. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1972

13. Hoffman KE, Voong KR, Levy LB, et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated, dose-escalated, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) versus conventionally fractionated IMRT for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(29):2943-2949. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.77.9868

14. Wilkins A, Mossop H, Syndikus I, et al. Hypofractionated radiotherapy versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with intermediate-risk localised prostate cancer: 2-year patient-reported outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1605-1616. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00280-6

15. Incrocci L, Wortel RC, Alemayehu WG, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with localised prostate cancer (HYPRO): final efficacy results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1061-1069. doi.10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30070-5

16. Arcangeli G, Saracino B, Arcangeli S, et al. Moderate hypofractionation in high-risk, organ-confined prostate cancer: final results of a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1891-1897. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4189

17. Aluwini S, Pos F, Schimmel E, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): late toxicity results from a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):464-474. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00567-7

18. Pervez N, Small C, MacKenzie M, et al. Acute toxicity in high-risk prostate cancer patients treated with androgen suppression and hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(1):57-64. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.048

19. Magli A, Moretti E, Tullio A, Giannarini G. Hypofractionated simultaneous integrated boost (IMRT- cancer: results of a prospective phase II trial SIB) with pelvic nodal irradiation and concurrent androgen deprivation therapy for high-risk prostate cancer: results of a prospective phase II trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21(2):269-276. doi:10.1038/s41391-018-0034-0

20. Di Muzio NG, Fodor A, Noris Chiorda B, et al. Moderate hypofractionation with simultaneous integrated boost in prostate cancer: long-term results of a phase I–II study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28(8):490-500. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2016.02.005

21. DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):21-233. doi:10.3322/caac.21555

22. Wolf MS, Knight SJ, Lyons EA, et al. Literacy, race, and PSA level among low-income men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Urology. 2006(1);68:89-93. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.064

23. Rebbeck TR. Prostate cancer disparities by race and ethnicity: from nucleotide to neighborhood. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(9):a030387. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a030387

24. Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, Winn RJ. Transportation as a barrier to cancer treatment. Cancer Pract. 1997;5(6):361-366.

25. Friedman DB, Corwin SJ, Dominick GM, Rose ID. African American men’s understanding and perceptions about prostate cancer: why multiple dimensions of health literacy are important in cancer communication. J Community Health. 2009;34(5):449-460. doi:10.1007/s10900-009-9167-3

26. Connell PP, Ignacio L, Haraf D, et al. Equivalent racial outcome after conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a single departmental experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):54-61. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.54

27. Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, et al. Association of black race with prostate cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(1):975-983. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.54

28. McKay RR, Sarkar RR, Kumar A, et al. Outcomes of Black men with prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2021;127(3):403-411. doi:10.1002/cncr.33224

29. Muralidhar V, Chen M-H, Reznor G, et al. Definition and validation of “favorable high-risk prostate cancer”: implications for personalizing treatment of radiation-managed patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93(4):828-835. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.07.2281

30. Roach M 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029

31. Freeman VL, Durazo-Arvizu R, Arozullah AM, Keys LC. Determinants of mortality following a diagnosis of prostate cancer in Veterans Affairs and private sector health care systems. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(100):1706-1712. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.10.1706

32. Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78-93. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78

33. Zemplenyi AT, Kaló Z, Kovacs G, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of intensity-modulated radiation therapy with normal and hypofractionated schemes for the treatment of localised prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(1):e12430. doi:10.1111/ecc.12430

34. Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kramer BS. Trends and black/white differences in treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Med Care. 1998;36(9):1337-1348. doi:10.1097/00005650-199809000-00006

35. Harlan L, Brawley O, Pommerenke F, Wali P, Kramer B. Geographic, age, and racial variation in the treatment of local/regional carcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):93-100. doi:10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.93

36. Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Racial equity among African-American and non-Hispanic white men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the veterans affairs healthcare system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105:E305.

37. Peterson K, Anderson J, Boundy E, Ferguson L, McCleery E, Waldrip K. Mortality disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups in the Veterans Health Administration: an evidence review and map. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):e1-e11. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304246

38. Zietman AL, DeSilvio ML, Slater JD, et al. Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(10):1233-1239. doi:10.1001/jama.294.10.1233

39. Hagan M, Kapoor R, Michalski J, et al. VA-Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(3):639-647. doi.10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.064

40. Carpenter DJ, Natesan D, Floyd W, et al. Long-term experience in an equal access health care system using moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy for high risk prostate cancer in a predominately African American population with unfavorable disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108(3):E417. https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(20)33923-7/fulltext

Although moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHRT) is an accepted treatment for localized prostate cancer, its adaptation remains limited in the United States.1,2 MHRT theoretically exploits α/β ratio differences between the prostate (1.5 Gy), bladder (5-10 Gy), and rectum (3 Gy), thereby reducing late treatment-related adverse effects compared with those of conventional fractionation at biologically equivalent doses.3-8 Multiple randomized noninferiority trials have demonstrated equivalent outcomes between MHRT and conventional fraction with no appreciable increase in patient-reported toxicity.9-14 Although these studies have led to the acceptance of MHRT as a standard treatment, the majority of these trials involve individuals with low- and intermediate-risk disease.

There are less phase 3 data addressing MHRT for high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).10,12,14-17 Only 2 studies examined predominately high-risk populations, accounting for 83 and 292 patients, respectively.15,16 Additional phase 3 trials with small proportions of high-risk patients (n = 126, 12%; n = 53, 35%) offer limited additional information regarding clinical outcomes and toxicity rates specific to high-risk disease.10-12 Numerous phase 1 and 2 studies report various field designs and fractionation plans for MHRT in the context of high-risk disease, although the applicability of these data to off-trial populations remains limited.18-20

Furthermore, African American individuals are underrepresented in the trials establishing the role of MHRT despite higher rates of prostate cancer incidence, more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and higher rates of prostate cancer–specific survival (PCSS) when compared with White patients.21 Racial disparities across patients with prostate cancer and their management are multifactorial across health care literacy, education level, access to care (including transportation issues), and issues of adherence and distrust.22-25 Correlation of patient race to prostate cancer outcomes varies greatly across health care systems, with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) equal access system providing robust mental health services and transportation services for some patients, while demonstrating similar rates of stage-adjusted PCSS between African American and White patients across a broad range of treatment modalities.26-28 Given the paucity of data exploring outcomes following MHRT for African American patients with HRPC, the present analysis provides long-term clinical outcomes and toxicity profiles for an off-trial majority African American population with HRPC treated with MHRT within the VA.

Methods

Records were retrospectively reviewed under an institutional review board–approved protocol for all patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT at the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in North Carolina between November 2008 and August 2018. Exclusion criteria included < 12 months of follow-up or elective nodal irradiation. Demographic variables obtained included age at diagnosis, race, clinical T stage, pre-MHRT prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason grade group at diagnosis, favorable vs unfavorable high-risk disease, pre-MHRT international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and pre-MHRT urinary medication usage (yes/no).29

Concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was initiated 6 to 8 weeks before MHRT unless medically contraindicated per the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. Patients generally received 18 to 24 months of ADT, with those with favorable HRPC (ie, T1c disease with either Gleason 4+4 and PSA < 10 mg/mL or Gleason 3+3 and PSA > 20 ng/mL) receiving 6 months after 2015.29 Patients were simulated supine in either standard or custom immobilization with a full bladder and empty rectum. MHRT fractionation plans included 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction and 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction. Radiotherapy targets included the prostate and seminal vesicles without elective nodal coverage per institutional practice. Treatments were delivered following image guidance, either prostate matching with cone beam computed tomography or fiducial matching with kilo voltage imaging. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy. For plans delivering 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction, constraints included bladder V (volume receiving) 70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 15%, V40 ≤ 35%, rectum V70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 10%, V40 ≤ 35%, femoral heads maximum point dose ≤ 40 Gy, penile bulb mean dose ≤ 50 Gy, and small bowel V40 ≤ 1%. For plans delivering 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction, constraints included rectum V57 ≤ 15%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, bladder V60 ≤ 5%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, and femoral heads V43 ≤ 5%.

Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicities were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0, with acute toxicity defined as on-treatment < 3 months following completion of MHRT. Late toxicity was defined as ≥ 3 months following completion of MHRT. Individuals were seen in follow-up at 6 weeks and 3 months with PSA and testosterone after MHRT completion, then every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter. Each follow-up visit included history, physical examination, IPSS, and CTCAE grading for GI and GU toxicity.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test and χ2 test were used to compare differences in demographic data, dosimetric parameters, and frequency of toxicity events with respect to patient race. Clinical endpoints including biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS; defined by Phoenix criteria as 2.0 above PSA nadir), distant metastases-free survival (DMFS), PCSS, and overall survival (OS) were estimated from time of radiotherapy completion by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between African American and White race by log-rank testing.30 Late GI and GU toxicity-free survival were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots and compared between African American and White patients by the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

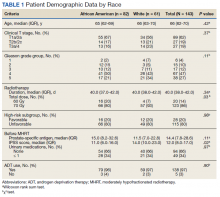

We identified 143 patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT between November 2008 and August 2018 (Table 1). Mean age was 65 years (range, 36-80 years); 57% were African American men. Eighty percent of individuals had unfavorable high-risk disease. Median (IQR) PSA was 14.4 (7.8-28.6). Twenty-six percent had grade group 1-3 disease, 47% had grade group 4 disease, and 27% had grade group 5 disease. African American patients had significantly lower pre-MHRT IPSS scores than White patients (mean IPSS, 11 vs 14, respectively; P = .02) despite similar rates of preradiotherapy urinary medication usage (66% and 66%, respectively).

Eighty-six percent received 70 Gy over 28 fractions, with institutional protocol shifting to 60 Gy over 20 fractions (14%) in June 2017. The median (IQR) duration of radiotherapy was 39 (38-42) days, with 97% of individuals undergoing ADT for a median (IQR) duration of 24 (24-36) months. The median follow-up time was 38 months, with 57 (40%) patients followed for at least 60 months.

Grade 3 GI and GU acute toxicity events were observed in 1% and 4% of all individuals, respectively (Table 2). No acute GI or GU grade 4+ events were observed. No significant differences in acute GU or GI toxicity were observed between African American and White patients.

No significant differences between African American and White patients were observed for late grade 2+ GI (P = .19) or GU (P = .55) toxicity. Late grade 2+ GI toxicity was observed in 17 (12%) patients overall (Figure 1A). One grade 3 and 1 grade 4 late GI event were observed following MHRT completion: The latter involved hospitalization for bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis in the context of cirrhosis predating MHRT. Late grade 2+ GU toxicity was observed in 80 (56%) patients, with late grade 2 events steadily increasing over time (Figure 1B). Nine late grade 3 GU toxicity events were observed at a median of 13 months following completion of MHRT, 2 of which occurred more than 24 months after MHRT completion. No late grade 4 or 5 GU events were observed. IPSS values both before MHRT and at time of last follow-up were available for 65 (40%) patients, with a median (IQR) IPSS of 10 (6-16) before MHRT and 12 (8-16) at last follow-up at a median (IQR) interval of 36 months (26-76) from radiation completion.

No significant differences were observed between African American and White patients with respect to BRFS, DMFS, PCSS, or OS (Figure 2). Overall, 21 of 143 (15%) patients experienced biochemical recurrence: 5-year BRFS was 77% (95% CI, 67%-85%) for all patients, 83% (95% CI, 70%-91%) for African American patients, and 71% (95% CI, 53%-82%) for White patients. Five-year DMFS was 87% (95% CI, 77%-92%) for all individuals, 91% (95% CI, 80%-96%) for African American patients, and 81% (95% CI, 62%-91%) for White patients. Five-year PCSS was 89% (95% CI, 80%-94%) for all patients, with 5-year PCSS rates of 90% (95% CI, 79%-95%) for African American patients and 87% (95% CI, 70%-95%) for White patients. Five-year OS was 75% overall (95% CI, 64%-82%), with 5-year OS rates of 73% (95% CI, 58%-83%) for African American patients and 77% (95% CI, 60%-87%) for White patients.

Discussion

In this study, we reported acute and late GI and GU toxicity rates as well as clinical outcomes for a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access health care environment. We found that MHRT was well tolerated with high rates of biochemical control, PCSS, and OS. Additionally, outcomes were not significantly different across patient race. To our knowledge, this is the first report of MHRT for HRPC in a majority African American population.

We found that MHRT was an effective treatment for patients with HRPC, in particular those with unfavorable high-risk disease. While prior prospective and randomized studies have investigated the use of MHRT, our series was larger than most and had a predominately unfavorable high-risk population.12,15-17 Our biochemical and PCSS rates compare favorably with those of HRPC trial populations, particularly given the high proportion of unfavorable high-risk disease.12,15,16 Despite similar rates of biochemical control, OS was lower in the present cohort than in HRPC trial populations, even with a younger median age at diagnosis. The similarly high rates of non–HRPC-related death across race may reflect differences in baseline comorbidities compared with trial populations as well as reported differences between individuals in the VA and the private sector.31 This suggests that MHRT can be an effective treatment for patients with unfavorable HRPC.

We did not find any differences in outcomes between African American and White individuals with HRPC treated with MHRT. Furthermore, our study demonstrates long-term rates of BRFS and PCSS in a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC that are comparable with those of prior randomized MHRT studies in high-risk, predominately White populations.12,15,16 Prior reports have found that African American men with HRPC may be at increased risk for inferior clinical outcomes due to a number of socioeconomic, biologic, and cultural mediators.26,27,32 Such individuals may disproportionally benefit from shorter treatment courses that improve access to radiotherapy, a well-documented disparity for African American men with localized prostate cancer.33-36 The VA is an ideal system for studying racial disparities within prostate cancer, as accessibility of mental health and transportation services, income, and insurance status are not barriers to preventative or acute care.37 Our results are concordant with those previously seen for African American patients with prostate cancer seen in the VA, which similarly demonstrate equal outcomes with those of other races.28,36 Incorporation of the earlier mentioned VA services into oncologic care across other health care systems could better characterize determinants of racial disparities in prostate cancer, including the prognostic significance of shortening treatment duration and number of patient visits via MHRT.

Despite widespread acceptance in prostate cancer radiotherapy guidelines, routine use of MHRT seems limited across all stages of localized prostate cancer.1,2 Late toxicity is a frequently noted concern regarding MHRT use. Higher rates of late grade 2+ GI toxicity were observed in the hypofractionation arm of the HYPRO trial.17 While RTOG 0415 did not include patients with HRPC, significantly higher rates of physician-reported (but not patient-reported) late grade 2+ GI and GU toxicity were observed using the same MHRT fractionation regimen used for the majority of individuals in our cohort.9 In our study, the steady increase in late grade 2 GU toxicity is consistent with what is seen following conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and is likely multifactorial.38 The mean IPSS difference of 2/35 from pre-MHRT baseline to the time of last follow-up suggests minimal quality of life decline. The relatively stable IPSSs over time alongside the > 50% prevalence of late grade 2 GU toxicity per CTCAE grading seems consistent with the discrepancy noted in RTOG 0415 between increased physician-reported late toxicity and favorable patient-reported quality of life scores.9 Moreover, significant variance exists in toxicity grading across scoring systems, revised editions of CTCAE, and physician-specific toxicity classification, particularly with regard to the use of adrenergic receptor blocker medications. In light of these factors, the high rate of late grade 2 GU toxicity in our study should be interpreted in the context of largely stable post-MHRT IPSSs and favorable rates of late GI grade 2+ and late GU grade 3+ toxicity.

Limitations

This study has several inherent limitations. While the size of the current HRPC cohort is notably larger than similar populations within the majority of phase 3 MHRT trials, these data derive from a single VA hospital. It is unclear whether these outcomes would be representative in a similar high-risk population receiving care outside of the VA equal access system. Follow-up data beyond 5 years was available for less than half of patients, partially due to nonprostate cancer–related mortality at a higher rate than observed in HRPC trial populations.12,15,16 Furthermore, all GI toxicity events were exclusively physician reported, and GU toxicity reporting was limited in the off-trial setting with not all patients routinely completing IPSS questionnaires following MHRT completion. However, all patients were treated similarly, and radiation quality was verified over the treatment period with mandated accreditation, frequent standardized output checks, and systematic treatment review.39

Conclusions

Patients with HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access, off-trial setting demonstrated favorable rates of biochemical control with acceptable rates of acute and late GI and GU toxicities. Clinical outcomes, including biochemical control, were not significantly different between African American and White patients, which may reflect equal access to care within the VA irrespective of income and insurance status. Incorporating VA services, such as access to primary care, mental health services, and transportation across other health care systems may aid in characterizing and mitigating racial and gender disparities in oncologic care.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were presented at the November 2020 ASTRO conference. 40

Although moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHRT) is an accepted treatment for localized prostate cancer, its adaptation remains limited in the United States.1,2 MHRT theoretically exploits α/β ratio differences between the prostate (1.5 Gy), bladder (5-10 Gy), and rectum (3 Gy), thereby reducing late treatment-related adverse effects compared with those of conventional fractionation at biologically equivalent doses.3-8 Multiple randomized noninferiority trials have demonstrated equivalent outcomes between MHRT and conventional fraction with no appreciable increase in patient-reported toxicity.9-14 Although these studies have led to the acceptance of MHRT as a standard treatment, the majority of these trials involve individuals with low- and intermediate-risk disease.

There are less phase 3 data addressing MHRT for high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).10,12,14-17 Only 2 studies examined predominately high-risk populations, accounting for 83 and 292 patients, respectively.15,16 Additional phase 3 trials with small proportions of high-risk patients (n = 126, 12%; n = 53, 35%) offer limited additional information regarding clinical outcomes and toxicity rates specific to high-risk disease.10-12 Numerous phase 1 and 2 studies report various field designs and fractionation plans for MHRT in the context of high-risk disease, although the applicability of these data to off-trial populations remains limited.18-20

Furthermore, African American individuals are underrepresented in the trials establishing the role of MHRT despite higher rates of prostate cancer incidence, more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and higher rates of prostate cancer–specific survival (PCSS) when compared with White patients.21 Racial disparities across patients with prostate cancer and their management are multifactorial across health care literacy, education level, access to care (including transportation issues), and issues of adherence and distrust.22-25 Correlation of patient race to prostate cancer outcomes varies greatly across health care systems, with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) equal access system providing robust mental health services and transportation services for some patients, while demonstrating similar rates of stage-adjusted PCSS between African American and White patients across a broad range of treatment modalities.26-28 Given the paucity of data exploring outcomes following MHRT for African American patients with HRPC, the present analysis provides long-term clinical outcomes and toxicity profiles for an off-trial majority African American population with HRPC treated with MHRT within the VA.

Methods

Records were retrospectively reviewed under an institutional review board–approved protocol for all patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT at the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in North Carolina between November 2008 and August 2018. Exclusion criteria included < 12 months of follow-up or elective nodal irradiation. Demographic variables obtained included age at diagnosis, race, clinical T stage, pre-MHRT prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason grade group at diagnosis, favorable vs unfavorable high-risk disease, pre-MHRT international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and pre-MHRT urinary medication usage (yes/no).29

Concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was initiated 6 to 8 weeks before MHRT unless medically contraindicated per the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. Patients generally received 18 to 24 months of ADT, with those with favorable HRPC (ie, T1c disease with either Gleason 4+4 and PSA < 10 mg/mL or Gleason 3+3 and PSA > 20 ng/mL) receiving 6 months after 2015.29 Patients were simulated supine in either standard or custom immobilization with a full bladder and empty rectum. MHRT fractionation plans included 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction and 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction. Radiotherapy targets included the prostate and seminal vesicles without elective nodal coverage per institutional practice. Treatments were delivered following image guidance, either prostate matching with cone beam computed tomography or fiducial matching with kilo voltage imaging. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy. For plans delivering 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction, constraints included bladder V (volume receiving) 70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 15%, V40 ≤ 35%, rectum V70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 10%, V40 ≤ 35%, femoral heads maximum point dose ≤ 40 Gy, penile bulb mean dose ≤ 50 Gy, and small bowel V40 ≤ 1%. For plans delivering 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction, constraints included rectum V57 ≤ 15%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, bladder V60 ≤ 5%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, and femoral heads V43 ≤ 5%.

Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicities were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0, with acute toxicity defined as on-treatment < 3 months following completion of MHRT. Late toxicity was defined as ≥ 3 months following completion of MHRT. Individuals were seen in follow-up at 6 weeks and 3 months with PSA and testosterone after MHRT completion, then every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter. Each follow-up visit included history, physical examination, IPSS, and CTCAE grading for GI and GU toxicity.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test and χ2 test were used to compare differences in demographic data, dosimetric parameters, and frequency of toxicity events with respect to patient race. Clinical endpoints including biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS; defined by Phoenix criteria as 2.0 above PSA nadir), distant metastases-free survival (DMFS), PCSS, and overall survival (OS) were estimated from time of radiotherapy completion by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between African American and White race by log-rank testing.30 Late GI and GU toxicity-free survival were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots and compared between African American and White patients by the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

We identified 143 patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT between November 2008 and August 2018 (Table 1). Mean age was 65 years (range, 36-80 years); 57% were African American men. Eighty percent of individuals had unfavorable high-risk disease. Median (IQR) PSA was 14.4 (7.8-28.6). Twenty-six percent had grade group 1-3 disease, 47% had grade group 4 disease, and 27% had grade group 5 disease. African American patients had significantly lower pre-MHRT IPSS scores than White patients (mean IPSS, 11 vs 14, respectively; P = .02) despite similar rates of preradiotherapy urinary medication usage (66% and 66%, respectively).

Eighty-six percent received 70 Gy over 28 fractions, with institutional protocol shifting to 60 Gy over 20 fractions (14%) in June 2017. The median (IQR) duration of radiotherapy was 39 (38-42) days, with 97% of individuals undergoing ADT for a median (IQR) duration of 24 (24-36) months. The median follow-up time was 38 months, with 57 (40%) patients followed for at least 60 months.

Grade 3 GI and GU acute toxicity events were observed in 1% and 4% of all individuals, respectively (Table 2). No acute GI or GU grade 4+ events were observed. No significant differences in acute GU or GI toxicity were observed between African American and White patients.

No significant differences between African American and White patients were observed for late grade 2+ GI (P = .19) or GU (P = .55) toxicity. Late grade 2+ GI toxicity was observed in 17 (12%) patients overall (Figure 1A). One grade 3 and 1 grade 4 late GI event were observed following MHRT completion: The latter involved hospitalization for bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis in the context of cirrhosis predating MHRT. Late grade 2+ GU toxicity was observed in 80 (56%) patients, with late grade 2 events steadily increasing over time (Figure 1B). Nine late grade 3 GU toxicity events were observed at a median of 13 months following completion of MHRT, 2 of which occurred more than 24 months after MHRT completion. No late grade 4 or 5 GU events were observed. IPSS values both before MHRT and at time of last follow-up were available for 65 (40%) patients, with a median (IQR) IPSS of 10 (6-16) before MHRT and 12 (8-16) at last follow-up at a median (IQR) interval of 36 months (26-76) from radiation completion.

No significant differences were observed between African American and White patients with respect to BRFS, DMFS, PCSS, or OS (Figure 2). Overall, 21 of 143 (15%) patients experienced biochemical recurrence: 5-year BRFS was 77% (95% CI, 67%-85%) for all patients, 83% (95% CI, 70%-91%) for African American patients, and 71% (95% CI, 53%-82%) for White patients. Five-year DMFS was 87% (95% CI, 77%-92%) for all individuals, 91% (95% CI, 80%-96%) for African American patients, and 81% (95% CI, 62%-91%) for White patients. Five-year PCSS was 89% (95% CI, 80%-94%) for all patients, with 5-year PCSS rates of 90% (95% CI, 79%-95%) for African American patients and 87% (95% CI, 70%-95%) for White patients. Five-year OS was 75% overall (95% CI, 64%-82%), with 5-year OS rates of 73% (95% CI, 58%-83%) for African American patients and 77% (95% CI, 60%-87%) for White patients.

Discussion

In this study, we reported acute and late GI and GU toxicity rates as well as clinical outcomes for a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access health care environment. We found that MHRT was well tolerated with high rates of biochemical control, PCSS, and OS. Additionally, outcomes were not significantly different across patient race. To our knowledge, this is the first report of MHRT for HRPC in a majority African American population.

We found that MHRT was an effective treatment for patients with HRPC, in particular those with unfavorable high-risk disease. While prior prospective and randomized studies have investigated the use of MHRT, our series was larger than most and had a predominately unfavorable high-risk population.12,15-17 Our biochemical and PCSS rates compare favorably with those of HRPC trial populations, particularly given the high proportion of unfavorable high-risk disease.12,15,16 Despite similar rates of biochemical control, OS was lower in the present cohort than in HRPC trial populations, even with a younger median age at diagnosis. The similarly high rates of non–HRPC-related death across race may reflect differences in baseline comorbidities compared with trial populations as well as reported differences between individuals in the VA and the private sector.31 This suggests that MHRT can be an effective treatment for patients with unfavorable HRPC.

We did not find any differences in outcomes between African American and White individuals with HRPC treated with MHRT. Furthermore, our study demonstrates long-term rates of BRFS and PCSS in a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC that are comparable with those of prior randomized MHRT studies in high-risk, predominately White populations.12,15,16 Prior reports have found that African American men with HRPC may be at increased risk for inferior clinical outcomes due to a number of socioeconomic, biologic, and cultural mediators.26,27,32 Such individuals may disproportionally benefit from shorter treatment courses that improve access to radiotherapy, a well-documented disparity for African American men with localized prostate cancer.33-36 The VA is an ideal system for studying racial disparities within prostate cancer, as accessibility of mental health and transportation services, income, and insurance status are not barriers to preventative or acute care.37 Our results are concordant with those previously seen for African American patients with prostate cancer seen in the VA, which similarly demonstrate equal outcomes with those of other races.28,36 Incorporation of the earlier mentioned VA services into oncologic care across other health care systems could better characterize determinants of racial disparities in prostate cancer, including the prognostic significance of shortening treatment duration and number of patient visits via MHRT.

Despite widespread acceptance in prostate cancer radiotherapy guidelines, routine use of MHRT seems limited across all stages of localized prostate cancer.1,2 Late toxicity is a frequently noted concern regarding MHRT use. Higher rates of late grade 2+ GI toxicity were observed in the hypofractionation arm of the HYPRO trial.17 While RTOG 0415 did not include patients with HRPC, significantly higher rates of physician-reported (but not patient-reported) late grade 2+ GI and GU toxicity were observed using the same MHRT fractionation regimen used for the majority of individuals in our cohort.9 In our study, the steady increase in late grade 2 GU toxicity is consistent with what is seen following conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and is likely multifactorial.38 The mean IPSS difference of 2/35 from pre-MHRT baseline to the time of last follow-up suggests minimal quality of life decline. The relatively stable IPSSs over time alongside the > 50% prevalence of late grade 2 GU toxicity per CTCAE grading seems consistent with the discrepancy noted in RTOG 0415 between increased physician-reported late toxicity and favorable patient-reported quality of life scores.9 Moreover, significant variance exists in toxicity grading across scoring systems, revised editions of CTCAE, and physician-specific toxicity classification, particularly with regard to the use of adrenergic receptor blocker medications. In light of these factors, the high rate of late grade 2 GU toxicity in our study should be interpreted in the context of largely stable post-MHRT IPSSs and favorable rates of late GI grade 2+ and late GU grade 3+ toxicity.

Limitations

This study has several inherent limitations. While the size of the current HRPC cohort is notably larger than similar populations within the majority of phase 3 MHRT trials, these data derive from a single VA hospital. It is unclear whether these outcomes would be representative in a similar high-risk population receiving care outside of the VA equal access system. Follow-up data beyond 5 years was available for less than half of patients, partially due to nonprostate cancer–related mortality at a higher rate than observed in HRPC trial populations.12,15,16 Furthermore, all GI toxicity events were exclusively physician reported, and GU toxicity reporting was limited in the off-trial setting with not all patients routinely completing IPSS questionnaires following MHRT completion. However, all patients were treated similarly, and radiation quality was verified over the treatment period with mandated accreditation, frequent standardized output checks, and systematic treatment review.39

Conclusions