User login

Gut Microbiome Influences Multiple Neurodegenerative Disorders

WASHINGTON, DC — Age-related neurodegenerative disorders — motor neuron diseases, demyelinating diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and other proteinopathies — are at an “inflection point,” said researcher Andrea R. Merchak, PhD, with a fuller understanding of disease pathophysiology but an overall dearth of effective disease-modifying treatments.

And this, Merchak said at the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2025, is where the gut microbiome comes in. “The gut-brain axis is important to take into consideration,” she urged, both for gut microbiome researchers — whose collaboration with neurologists and neuroscientists is essential — and for practicing gastroenterologists.

“We are the sum of our environmental exposures,” said Merchak, assistant research professor of neurology at the Indiana University School of Medicine, in Indianapolis. “So for your patient populations, remember you’re not only treating the diseases they’re coming to you with, you’re also treating them for a lifetime of healthy [brain] aging.”

At the center of a healthy aging brain are the brain-residing microglia and peripheral monocytes, she said. These immune cell populations are directly influenced by blood-brain barrier breakdown, inflammation, and gut permeability — and indirectly influenced by microbial products, gastrointestinal (GI) function, and bacterial diversity, Merchak said at the meeting, which was convened by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.

“Many of us grew up learning that the brain is an immune-privileged site, but we’ve been establishing that this is fundamentally not true,” she said. “While the brain does have a privileged status, there are interactions with the blood, with the peripheral immune cells.”

Merchak coauthored a 2024 review in Neurotherapeutics in which she and her colleagues explained that the brain is “heavily connected with peripheral immune dynamics,” and that the gut — as the largest immune organ in the body — is a critical place for peripheral immune development, “thus influencing brain health.”

Gut microbiota interact with the brain via several mechanisms including microbiota-derived metabolites that enter circulation, direct communication via the vagus nerve, and modulation of the immune system, Merchak and her coauthors wrote. Leaky gut, they noted, can lead to an accumulation of inflammatory signals and cells that can exacerbate or induce the onset of neurodegenerative conditions.

As researchers better understand the role that GI dysfunction plays in neurodegenerative disease — as they identify microbiome signatures for predicting risk, for instance — there will be “opportunities to target the microbiome to prevent or reverse dysbiosis as a way to delay, arrest or prevent the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases,” they wrote.

At the GMFH meeting, Merchak described both ongoing preclinical research that is dissecting gut-brain communication, and preliminary clinical evidence for the use of gut microbiota-modulating therapies in neurodegenerative disease.

Support for a Gut-Focused Approach

Research on bile acid metabolism in multiple sclerosis (MS) and on peripheral inflammation in dementia exemplify the ongoing preclinical research uncovering the mechanisms of gut-brain communication, Merchak said.

The finding that bile acid metabolism modulates MS autoimmunity comes from research done by Merchak and a team at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, several years ago in which mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) — an animal model of MS — were engineered for T cell specific knockout of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). The AHR has been directly tied to MS, and T lymphocytes are known to play a central role in MS pathophysiology.

Blocking the activity of AHR in CD4-positive T cells significantly affected the production of bile acids and other metabolites in the microbiome — and the outcome of central nervous system autoimmunity. “Mice with high levels of bile acids, both primary and secondary, actually recovered from this EAE” and regained motor function, Merchak said at the GMFH meeting.

The potential impact of genetic manipulation on recovery was ruled out — and the role of bile acids confirmed — when, using the EAE model, gut bacteria from mice without AHR were transplanted into mice with AHR. The mice with AHR were able to recover, confirming that AHR can reprogram the gut microbiome and that “high levels of bile acid can lead to reduced autoimmunity in an MS model,” she said.

Other elements and stages of the research, which was published in PLOS Biology in 2023, showed increased apoptosis of CD4-positive immune cells in AHR-deficient mice and the ability of oral taurocholic acid — a bile acid that was especially high in mice without AHR — to reduce the severity of EAE, Merchak said.

Evidence for the role of gut and peripheral inflammation on neurodegeneration is building on numerous fronts, Merchak said. Unpublished research using spatial transcriptomics of colon biopsies from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), and neurologically healthy control individuals, for instance, showed similar cell communication patterns in patients with IBD or PD (and no history of IBD) compared with healthy control individuals.

And in research using a single-cell genomics approach and a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced system neuroinflammation, microglia were found to preferentially communicate with peripheral myeloid cells rather than other microglia after peripheral LPS exposure.

“In saline-treated mice, the microglia are talking primarily to microglia, but in LPS-treated mice, microglia spend more time communicating with monocytes and T cells,” Merchak explained. “We see communication going from inside the brain to cells coming in from the periphery.”

In another experiment, 2 months of a high-fat, high-sugar diet in mice with an engineered predisposition to frontotemporal dementia led to significant upregulation of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) expression on monocytes in the brain, she said, describing unpublished research. Because MHC II handles antigen presentation in the brain, the change signals increased central-peripheral immune crosstalk and increased brain inflammation.

State of Clinical Research

On the clinical side, Merchak said studies of gut microbiome-modulating therapies are currently not longitudinal enough to accurately study neurodegenerative diseases that may develop over decades. Still, her review of the literature — part of her 2024 article — suggests there is at least some preliminary clinical evidence for the use of probiotics/prebiotics/diet and fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in several diseases.

- Parkinson’s Disease: “There has been some evidence,” Merchak said at the meeting, “for the treatment [with probiotics, prebiotics and diet] of nonmotor symptoms — things like gastrointestinal distress and mood changes — but no real evidence that such treatments can help with the motor symptoms we see in Parkinson’s.” Over 60 patients with PD have been treated with FMT, she said, with reduced GI distress and mixed results with motor symptoms.

- Alzheimer’s and related dementias: “Diet shows promise for cognitive outcomes, but there hasn’t been much evidence for probiotics,” she said. Her review found 17 patients diagnosed with dementia who were treated with FMT, “and for many of them, maintenance of cognitive function was reported — so no further decline — which is excellent.”

- Multiple Sclerosis: “We see higher quality-of-life measures in patients getting probiotics, prebiotics, and changes in diet,” Merchak said. “Again, most of this [relates to] mood and digestion, but some studies show a slowing of neurological damage as measured by MRI.”

There are reports of 15 patients treated with FMT, and “three of these document full functional recovery,” she said, noting that longer follow-up is necessary as MS is characterized by relapsed and periods of recovery.

Merchak reported no financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON, DC — Age-related neurodegenerative disorders — motor neuron diseases, demyelinating diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and other proteinopathies — are at an “inflection point,” said researcher Andrea R. Merchak, PhD, with a fuller understanding of disease pathophysiology but an overall dearth of effective disease-modifying treatments.

And this, Merchak said at the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2025, is where the gut microbiome comes in. “The gut-brain axis is important to take into consideration,” she urged, both for gut microbiome researchers — whose collaboration with neurologists and neuroscientists is essential — and for practicing gastroenterologists.

“We are the sum of our environmental exposures,” said Merchak, assistant research professor of neurology at the Indiana University School of Medicine, in Indianapolis. “So for your patient populations, remember you’re not only treating the diseases they’re coming to you with, you’re also treating them for a lifetime of healthy [brain] aging.”

At the center of a healthy aging brain are the brain-residing microglia and peripheral monocytes, she said. These immune cell populations are directly influenced by blood-brain barrier breakdown, inflammation, and gut permeability — and indirectly influenced by microbial products, gastrointestinal (GI) function, and bacterial diversity, Merchak said at the meeting, which was convened by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.

“Many of us grew up learning that the brain is an immune-privileged site, but we’ve been establishing that this is fundamentally not true,” she said. “While the brain does have a privileged status, there are interactions with the blood, with the peripheral immune cells.”

Merchak coauthored a 2024 review in Neurotherapeutics in which she and her colleagues explained that the brain is “heavily connected with peripheral immune dynamics,” and that the gut — as the largest immune organ in the body — is a critical place for peripheral immune development, “thus influencing brain health.”

Gut microbiota interact with the brain via several mechanisms including microbiota-derived metabolites that enter circulation, direct communication via the vagus nerve, and modulation of the immune system, Merchak and her coauthors wrote. Leaky gut, they noted, can lead to an accumulation of inflammatory signals and cells that can exacerbate or induce the onset of neurodegenerative conditions.

As researchers better understand the role that GI dysfunction plays in neurodegenerative disease — as they identify microbiome signatures for predicting risk, for instance — there will be “opportunities to target the microbiome to prevent or reverse dysbiosis as a way to delay, arrest or prevent the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases,” they wrote.

At the GMFH meeting, Merchak described both ongoing preclinical research that is dissecting gut-brain communication, and preliminary clinical evidence for the use of gut microbiota-modulating therapies in neurodegenerative disease.

Support for a Gut-Focused Approach

Research on bile acid metabolism in multiple sclerosis (MS) and on peripheral inflammation in dementia exemplify the ongoing preclinical research uncovering the mechanisms of gut-brain communication, Merchak said.

The finding that bile acid metabolism modulates MS autoimmunity comes from research done by Merchak and a team at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, several years ago in which mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) — an animal model of MS — were engineered for T cell specific knockout of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). The AHR has been directly tied to MS, and T lymphocytes are known to play a central role in MS pathophysiology.

Blocking the activity of AHR in CD4-positive T cells significantly affected the production of bile acids and other metabolites in the microbiome — and the outcome of central nervous system autoimmunity. “Mice with high levels of bile acids, both primary and secondary, actually recovered from this EAE” and regained motor function, Merchak said at the GMFH meeting.

The potential impact of genetic manipulation on recovery was ruled out — and the role of bile acids confirmed — when, using the EAE model, gut bacteria from mice without AHR were transplanted into mice with AHR. The mice with AHR were able to recover, confirming that AHR can reprogram the gut microbiome and that “high levels of bile acid can lead to reduced autoimmunity in an MS model,” she said.

Other elements and stages of the research, which was published in PLOS Biology in 2023, showed increased apoptosis of CD4-positive immune cells in AHR-deficient mice and the ability of oral taurocholic acid — a bile acid that was especially high in mice without AHR — to reduce the severity of EAE, Merchak said.

Evidence for the role of gut and peripheral inflammation on neurodegeneration is building on numerous fronts, Merchak said. Unpublished research using spatial transcriptomics of colon biopsies from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), and neurologically healthy control individuals, for instance, showed similar cell communication patterns in patients with IBD or PD (and no history of IBD) compared with healthy control individuals.

And in research using a single-cell genomics approach and a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced system neuroinflammation, microglia were found to preferentially communicate with peripheral myeloid cells rather than other microglia after peripheral LPS exposure.

“In saline-treated mice, the microglia are talking primarily to microglia, but in LPS-treated mice, microglia spend more time communicating with monocytes and T cells,” Merchak explained. “We see communication going from inside the brain to cells coming in from the periphery.”

In another experiment, 2 months of a high-fat, high-sugar diet in mice with an engineered predisposition to frontotemporal dementia led to significant upregulation of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) expression on monocytes in the brain, she said, describing unpublished research. Because MHC II handles antigen presentation in the brain, the change signals increased central-peripheral immune crosstalk and increased brain inflammation.

State of Clinical Research

On the clinical side, Merchak said studies of gut microbiome-modulating therapies are currently not longitudinal enough to accurately study neurodegenerative diseases that may develop over decades. Still, her review of the literature — part of her 2024 article — suggests there is at least some preliminary clinical evidence for the use of probiotics/prebiotics/diet and fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in several diseases.

- Parkinson’s Disease: “There has been some evidence,” Merchak said at the meeting, “for the treatment [with probiotics, prebiotics and diet] of nonmotor symptoms — things like gastrointestinal distress and mood changes — but no real evidence that such treatments can help with the motor symptoms we see in Parkinson’s.” Over 60 patients with PD have been treated with FMT, she said, with reduced GI distress and mixed results with motor symptoms.

- Alzheimer’s and related dementias: “Diet shows promise for cognitive outcomes, but there hasn’t been much evidence for probiotics,” she said. Her review found 17 patients diagnosed with dementia who were treated with FMT, “and for many of them, maintenance of cognitive function was reported — so no further decline — which is excellent.”

- Multiple Sclerosis: “We see higher quality-of-life measures in patients getting probiotics, prebiotics, and changes in diet,” Merchak said. “Again, most of this [relates to] mood and digestion, but some studies show a slowing of neurological damage as measured by MRI.”

There are reports of 15 patients treated with FMT, and “three of these document full functional recovery,” she said, noting that longer follow-up is necessary as MS is characterized by relapsed and periods of recovery.

Merchak reported no financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON, DC — Age-related neurodegenerative disorders — motor neuron diseases, demyelinating diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and other proteinopathies — are at an “inflection point,” said researcher Andrea R. Merchak, PhD, with a fuller understanding of disease pathophysiology but an overall dearth of effective disease-modifying treatments.

And this, Merchak said at the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2025, is where the gut microbiome comes in. “The gut-brain axis is important to take into consideration,” she urged, both for gut microbiome researchers — whose collaboration with neurologists and neuroscientists is essential — and for practicing gastroenterologists.

“We are the sum of our environmental exposures,” said Merchak, assistant research professor of neurology at the Indiana University School of Medicine, in Indianapolis. “So for your patient populations, remember you’re not only treating the diseases they’re coming to you with, you’re also treating them for a lifetime of healthy [brain] aging.”

At the center of a healthy aging brain are the brain-residing microglia and peripheral monocytes, she said. These immune cell populations are directly influenced by blood-brain barrier breakdown, inflammation, and gut permeability — and indirectly influenced by microbial products, gastrointestinal (GI) function, and bacterial diversity, Merchak said at the meeting, which was convened by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility.

“Many of us grew up learning that the brain is an immune-privileged site, but we’ve been establishing that this is fundamentally not true,” she said. “While the brain does have a privileged status, there are interactions with the blood, with the peripheral immune cells.”

Merchak coauthored a 2024 review in Neurotherapeutics in which she and her colleagues explained that the brain is “heavily connected with peripheral immune dynamics,” and that the gut — as the largest immune organ in the body — is a critical place for peripheral immune development, “thus influencing brain health.”

Gut microbiota interact with the brain via several mechanisms including microbiota-derived metabolites that enter circulation, direct communication via the vagus nerve, and modulation of the immune system, Merchak and her coauthors wrote. Leaky gut, they noted, can lead to an accumulation of inflammatory signals and cells that can exacerbate or induce the onset of neurodegenerative conditions.

As researchers better understand the role that GI dysfunction plays in neurodegenerative disease — as they identify microbiome signatures for predicting risk, for instance — there will be “opportunities to target the microbiome to prevent or reverse dysbiosis as a way to delay, arrest or prevent the onset and progression of neurodegenerative diseases,” they wrote.

At the GMFH meeting, Merchak described both ongoing preclinical research that is dissecting gut-brain communication, and preliminary clinical evidence for the use of gut microbiota-modulating therapies in neurodegenerative disease.

Support for a Gut-Focused Approach

Research on bile acid metabolism in multiple sclerosis (MS) and on peripheral inflammation in dementia exemplify the ongoing preclinical research uncovering the mechanisms of gut-brain communication, Merchak said.

The finding that bile acid metabolism modulates MS autoimmunity comes from research done by Merchak and a team at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, several years ago in which mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) — an animal model of MS — were engineered for T cell specific knockout of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). The AHR has been directly tied to MS, and T lymphocytes are known to play a central role in MS pathophysiology.

Blocking the activity of AHR in CD4-positive T cells significantly affected the production of bile acids and other metabolites in the microbiome — and the outcome of central nervous system autoimmunity. “Mice with high levels of bile acids, both primary and secondary, actually recovered from this EAE” and regained motor function, Merchak said at the GMFH meeting.

The potential impact of genetic manipulation on recovery was ruled out — and the role of bile acids confirmed — when, using the EAE model, gut bacteria from mice without AHR were transplanted into mice with AHR. The mice with AHR were able to recover, confirming that AHR can reprogram the gut microbiome and that “high levels of bile acid can lead to reduced autoimmunity in an MS model,” she said.

Other elements and stages of the research, which was published in PLOS Biology in 2023, showed increased apoptosis of CD4-positive immune cells in AHR-deficient mice and the ability of oral taurocholic acid — a bile acid that was especially high in mice without AHR — to reduce the severity of EAE, Merchak said.

Evidence for the role of gut and peripheral inflammation on neurodegeneration is building on numerous fronts, Merchak said. Unpublished research using spatial transcriptomics of colon biopsies from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), and neurologically healthy control individuals, for instance, showed similar cell communication patterns in patients with IBD or PD (and no history of IBD) compared with healthy control individuals.

And in research using a single-cell genomics approach and a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced system neuroinflammation, microglia were found to preferentially communicate with peripheral myeloid cells rather than other microglia after peripheral LPS exposure.

“In saline-treated mice, the microglia are talking primarily to microglia, but in LPS-treated mice, microglia spend more time communicating with monocytes and T cells,” Merchak explained. “We see communication going from inside the brain to cells coming in from the periphery.”

In another experiment, 2 months of a high-fat, high-sugar diet in mice with an engineered predisposition to frontotemporal dementia led to significant upregulation of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) expression on monocytes in the brain, she said, describing unpublished research. Because MHC II handles antigen presentation in the brain, the change signals increased central-peripheral immune crosstalk and increased brain inflammation.

State of Clinical Research

On the clinical side, Merchak said studies of gut microbiome-modulating therapies are currently not longitudinal enough to accurately study neurodegenerative diseases that may develop over decades. Still, her review of the literature — part of her 2024 article — suggests there is at least some preliminary clinical evidence for the use of probiotics/prebiotics/diet and fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) in several diseases.

- Parkinson’s Disease: “There has been some evidence,” Merchak said at the meeting, “for the treatment [with probiotics, prebiotics and diet] of nonmotor symptoms — things like gastrointestinal distress and mood changes — but no real evidence that such treatments can help with the motor symptoms we see in Parkinson’s.” Over 60 patients with PD have been treated with FMT, she said, with reduced GI distress and mixed results with motor symptoms.

- Alzheimer’s and related dementias: “Diet shows promise for cognitive outcomes, but there hasn’t been much evidence for probiotics,” she said. Her review found 17 patients diagnosed with dementia who were treated with FMT, “and for many of them, maintenance of cognitive function was reported — so no further decline — which is excellent.”

- Multiple Sclerosis: “We see higher quality-of-life measures in patients getting probiotics, prebiotics, and changes in diet,” Merchak said. “Again, most of this [relates to] mood and digestion, but some studies show a slowing of neurological damage as measured by MRI.”

There are reports of 15 patients treated with FMT, and “three of these document full functional recovery,” she said, noting that longer follow-up is necessary as MS is characterized by relapsed and periods of recovery.

Merchak reported no financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM GMFH 2025

Five Reasons to Update Your Will

You have a will, so you can rest easy, right? Not necessarily. If your will is outdated, it can cause more harm than good.

Even though it can provide for some contingencies, an old will can’t cover every change that may have occurred since it was first drawn. Professionals advise that you review your will every few years and more often if situations such as the following five have occurred since you last updated your will.

1. Family Changes

If you’ve had any changes in your family situation, you will probably need to update your will. Events such as marriage, divorce, death, birth, adoption, or a falling out with a loved one may affect how your estate will be distributed, who should act as guardian for your dependents, and who should be named as executor of your estate.

2. Relocating to a New State

The laws among the states vary. Moving to a new state or purchasing property in another state can affect your estate plan and how property in that state will be taxed and distributed.

3. Tax Law Changes

Federal and state legislatures are continually tinkering with federal estate and state inheritance tax laws. An old will may fail to take advantage of strategies that will minimize estate taxes.

4. You Want to Support a Favorite Cause

If you have developed a connection to a cause, you may want to benefit a particular charity with a gift in your estate. Contact us for sample language you can share with your attorney to include a gift to us in your will.

5. Changes in Your Estate’s Value

When you made your will, your assets may have been relatively modest. Now the value may be larger and your will no longer reflects how you would like your estate divided.

You will help spark future discoveries in GI. Visit our website at https://gastro.planmylegacy.org or contact us at foundation@gastro.org.

You have a will, so you can rest easy, right? Not necessarily. If your will is outdated, it can cause more harm than good.

Even though it can provide for some contingencies, an old will can’t cover every change that may have occurred since it was first drawn. Professionals advise that you review your will every few years and more often if situations such as the following five have occurred since you last updated your will.

1. Family Changes

If you’ve had any changes in your family situation, you will probably need to update your will. Events such as marriage, divorce, death, birth, adoption, or a falling out with a loved one may affect how your estate will be distributed, who should act as guardian for your dependents, and who should be named as executor of your estate.

2. Relocating to a New State

The laws among the states vary. Moving to a new state or purchasing property in another state can affect your estate plan and how property in that state will be taxed and distributed.

3. Tax Law Changes

Federal and state legislatures are continually tinkering with federal estate and state inheritance tax laws. An old will may fail to take advantage of strategies that will minimize estate taxes.

4. You Want to Support a Favorite Cause

If you have developed a connection to a cause, you may want to benefit a particular charity with a gift in your estate. Contact us for sample language you can share with your attorney to include a gift to us in your will.

5. Changes in Your Estate’s Value

When you made your will, your assets may have been relatively modest. Now the value may be larger and your will no longer reflects how you would like your estate divided.

You will help spark future discoveries in GI. Visit our website at https://gastro.planmylegacy.org or contact us at foundation@gastro.org.

You have a will, so you can rest easy, right? Not necessarily. If your will is outdated, it can cause more harm than good.

Even though it can provide for some contingencies, an old will can’t cover every change that may have occurred since it was first drawn. Professionals advise that you review your will every few years and more often if situations such as the following five have occurred since you last updated your will.

1. Family Changes

If you’ve had any changes in your family situation, you will probably need to update your will. Events such as marriage, divorce, death, birth, adoption, or a falling out with a loved one may affect how your estate will be distributed, who should act as guardian for your dependents, and who should be named as executor of your estate.

2. Relocating to a New State

The laws among the states vary. Moving to a new state or purchasing property in another state can affect your estate plan and how property in that state will be taxed and distributed.

3. Tax Law Changes

Federal and state legislatures are continually tinkering with federal estate and state inheritance tax laws. An old will may fail to take advantage of strategies that will minimize estate taxes.

4. You Want to Support a Favorite Cause

If you have developed a connection to a cause, you may want to benefit a particular charity with a gift in your estate. Contact us for sample language you can share with your attorney to include a gift to us in your will.

5. Changes in Your Estate’s Value

When you made your will, your assets may have been relatively modest. Now the value may be larger and your will no longer reflects how you would like your estate divided.

You will help spark future discoveries in GI. Visit our website at https://gastro.planmylegacy.org or contact us at foundation@gastro.org.

Simple Score Predicts Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia in Young Adults

While colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence has declined overall due to screening, early-onset CRC is on the rise, particularly in individuals younger than 45 years — an age group not currently recommended for CRC screening.

Studies have shown that the risk for early-onset advanced neoplasia varies based on several factors, including sex, race, family history of CRC, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diet.

A score that incorporates some of these factors to identify which younger adults are at higher risk for advanced neoplasia, a precursor to CRC, could support earlier, more targeted screening interventions.

The simple clinical score can be easily calculated by primary care providers in the office, Carole Macaron, MD, lead author of the study and a gastroenterologist at Cleveland Clinic, told GI & Hepatology News. “Patients with a high-risk score would be referred for colorectal cancer screening.”

The study was published in Digestive Diseases and Sciences.

To develop and validate their risk score, Macaron and colleagues did a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 9446 individuals aged 18-44 years (mean age, 36.8 years; 61% women) who underwent colonoscopy at their center.

Advanced neoplasia was defined as a tubular adenoma ≥ 10 mm or any adenoma with villous features or high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10 mm, sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma.

The 346 (3.7%) individuals found to have advanced neoplasia served as the case group, and the remainder with normal colonoscopy or non-advanced neoplasia served as controls.

A multivariate logistic regression model identified three independent risk factors significantly associated with advanced neoplasia: Higher body mass index (BMI; P = .0157), former and current tobacco use (P = .0009 and P = .0015, respectively), and having a first-degree relative with CRC < 60 years (P < .0001) or other family history of CRC (P = .0117).

The researchers used these risk factors to develop a risk prediction score to estimate the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia, which ranged from a risk of 1.8% for patients with a score of 1 to 22.2% for those with a score of 12. Individuals with a score of ≥ 9 had a 14% or higher risk for advanced neoplasia.

Based on the risk model, the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia in an asymptomatic 32-year-old overweight individual, with a history of previous tobacco use and a first-degree relative younger than age 60 with CRC would be 20.3%, Macaron and colleagues noted.

The model demonstrated “moderate” discriminatory power in the validation set (C-statistic: 0.645), indicating that it can effectively differentiate between individuals at a higher and lower risk for advanced neoplasia.

Additionally, the authors are exploring ways to improve the discriminatory power of the score, possibly by including additional risk factors.

Given the score is calculated using easily obtainable risk factors for individuals younger than 45 who are at risk for early-onset colorectal neoplasia, it could help guide individualized screening decisions for those in whom screening is not currently offered, Macaron said. It could also serve as a tool for risk communication and shared decision-making.

Integration into electronic health records or online calculators may enhance its accessibility and clinical utility.

The authors noted that this retrospective study was conducted at a single center caring mainly for White non-Hispanic adults, limiting generalizability to the general population and to other races and ethnicities.

Validation in Real-World Setting Needed

“There are no currently accepted advanced colorectal neoplasia risk scores that are used in general practice,” said Steven H. Itzkowitz, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, oncological sciences, and medical education, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “If these lesions can be predicted, it would enable these young individuals to undergo screening colonoscopy, which could detect and remove these lesions, thereby preventing CRC.”

Many of the known risk factors (family history, high BMI, or smoking) for CRC development at any age are incorporated within this tool, so it should be feasible to collect these data,” said Itzkowitz, who was not involved with the study.

But he cautioned that accurate and adequate family histories are not always performed. Clinicians also may not have considered combining these factors into an actionable risk score.

“If this score can be externally validated in a real-world setting, it could be a useful addition in our efforts to lower CRC rates among young individuals,” Itzkowitz said.

The study did not receive any funding. Macaron and Itzkowitz reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence has declined overall due to screening, early-onset CRC is on the rise, particularly in individuals younger than 45 years — an age group not currently recommended for CRC screening.

Studies have shown that the risk for early-onset advanced neoplasia varies based on several factors, including sex, race, family history of CRC, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diet.

A score that incorporates some of these factors to identify which younger adults are at higher risk for advanced neoplasia, a precursor to CRC, could support earlier, more targeted screening interventions.

The simple clinical score can be easily calculated by primary care providers in the office, Carole Macaron, MD, lead author of the study and a gastroenterologist at Cleveland Clinic, told GI & Hepatology News. “Patients with a high-risk score would be referred for colorectal cancer screening.”

The study was published in Digestive Diseases and Sciences.

To develop and validate their risk score, Macaron and colleagues did a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 9446 individuals aged 18-44 years (mean age, 36.8 years; 61% women) who underwent colonoscopy at their center.

Advanced neoplasia was defined as a tubular adenoma ≥ 10 mm or any adenoma with villous features or high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10 mm, sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma.

The 346 (3.7%) individuals found to have advanced neoplasia served as the case group, and the remainder with normal colonoscopy or non-advanced neoplasia served as controls.

A multivariate logistic regression model identified three independent risk factors significantly associated with advanced neoplasia: Higher body mass index (BMI; P = .0157), former and current tobacco use (P = .0009 and P = .0015, respectively), and having a first-degree relative with CRC < 60 years (P < .0001) or other family history of CRC (P = .0117).

The researchers used these risk factors to develop a risk prediction score to estimate the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia, which ranged from a risk of 1.8% for patients with a score of 1 to 22.2% for those with a score of 12. Individuals with a score of ≥ 9 had a 14% or higher risk for advanced neoplasia.

Based on the risk model, the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia in an asymptomatic 32-year-old overweight individual, with a history of previous tobacco use and a first-degree relative younger than age 60 with CRC would be 20.3%, Macaron and colleagues noted.

The model demonstrated “moderate” discriminatory power in the validation set (C-statistic: 0.645), indicating that it can effectively differentiate between individuals at a higher and lower risk for advanced neoplasia.

Additionally, the authors are exploring ways to improve the discriminatory power of the score, possibly by including additional risk factors.

Given the score is calculated using easily obtainable risk factors for individuals younger than 45 who are at risk for early-onset colorectal neoplasia, it could help guide individualized screening decisions for those in whom screening is not currently offered, Macaron said. It could also serve as a tool for risk communication and shared decision-making.

Integration into electronic health records or online calculators may enhance its accessibility and clinical utility.

The authors noted that this retrospective study was conducted at a single center caring mainly for White non-Hispanic adults, limiting generalizability to the general population and to other races and ethnicities.

Validation in Real-World Setting Needed

“There are no currently accepted advanced colorectal neoplasia risk scores that are used in general practice,” said Steven H. Itzkowitz, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, oncological sciences, and medical education, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “If these lesions can be predicted, it would enable these young individuals to undergo screening colonoscopy, which could detect and remove these lesions, thereby preventing CRC.”

Many of the known risk factors (family history, high BMI, or smoking) for CRC development at any age are incorporated within this tool, so it should be feasible to collect these data,” said Itzkowitz, who was not involved with the study.

But he cautioned that accurate and adequate family histories are not always performed. Clinicians also may not have considered combining these factors into an actionable risk score.

“If this score can be externally validated in a real-world setting, it could be a useful addition in our efforts to lower CRC rates among young individuals,” Itzkowitz said.

The study did not receive any funding. Macaron and Itzkowitz reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence has declined overall due to screening, early-onset CRC is on the rise, particularly in individuals younger than 45 years — an age group not currently recommended for CRC screening.

Studies have shown that the risk for early-onset advanced neoplasia varies based on several factors, including sex, race, family history of CRC, smoking, alcohol consumption, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diet.

A score that incorporates some of these factors to identify which younger adults are at higher risk for advanced neoplasia, a precursor to CRC, could support earlier, more targeted screening interventions.

The simple clinical score can be easily calculated by primary care providers in the office, Carole Macaron, MD, lead author of the study and a gastroenterologist at Cleveland Clinic, told GI & Hepatology News. “Patients with a high-risk score would be referred for colorectal cancer screening.”

The study was published in Digestive Diseases and Sciences.

To develop and validate their risk score, Macaron and colleagues did a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 9446 individuals aged 18-44 years (mean age, 36.8 years; 61% women) who underwent colonoscopy at their center.

Advanced neoplasia was defined as a tubular adenoma ≥ 10 mm or any adenoma with villous features or high-grade dysplasia, sessile serrated polyp ≥ 10 mm, sessile serrated polyp with dysplasia, traditional serrated adenoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma.

The 346 (3.7%) individuals found to have advanced neoplasia served as the case group, and the remainder with normal colonoscopy or non-advanced neoplasia served as controls.

A multivariate logistic regression model identified three independent risk factors significantly associated with advanced neoplasia: Higher body mass index (BMI; P = .0157), former and current tobacco use (P = .0009 and P = .0015, respectively), and having a first-degree relative with CRC < 60 years (P < .0001) or other family history of CRC (P = .0117).

The researchers used these risk factors to develop a risk prediction score to estimate the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia, which ranged from a risk of 1.8% for patients with a score of 1 to 22.2% for those with a score of 12. Individuals with a score of ≥ 9 had a 14% or higher risk for advanced neoplasia.

Based on the risk model, the likelihood of detecting advanced neoplasia in an asymptomatic 32-year-old overweight individual, with a history of previous tobacco use and a first-degree relative younger than age 60 with CRC would be 20.3%, Macaron and colleagues noted.

The model demonstrated “moderate” discriminatory power in the validation set (C-statistic: 0.645), indicating that it can effectively differentiate between individuals at a higher and lower risk for advanced neoplasia.

Additionally, the authors are exploring ways to improve the discriminatory power of the score, possibly by including additional risk factors.

Given the score is calculated using easily obtainable risk factors for individuals younger than 45 who are at risk for early-onset colorectal neoplasia, it could help guide individualized screening decisions for those in whom screening is not currently offered, Macaron said. It could also serve as a tool for risk communication and shared decision-making.

Integration into electronic health records or online calculators may enhance its accessibility and clinical utility.

The authors noted that this retrospective study was conducted at a single center caring mainly for White non-Hispanic adults, limiting generalizability to the general population and to other races and ethnicities.

Validation in Real-World Setting Needed

“There are no currently accepted advanced colorectal neoplasia risk scores that are used in general practice,” said Steven H. Itzkowitz, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, oncological sciences, and medical education, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “If these lesions can be predicted, it would enable these young individuals to undergo screening colonoscopy, which could detect and remove these lesions, thereby preventing CRC.”

Many of the known risk factors (family history, high BMI, or smoking) for CRC development at any age are incorporated within this tool, so it should be feasible to collect these data,” said Itzkowitz, who was not involved with the study.

But he cautioned that accurate and adequate family histories are not always performed. Clinicians also may not have considered combining these factors into an actionable risk score.

“If this score can be externally validated in a real-world setting, it could be a useful addition in our efforts to lower CRC rates among young individuals,” Itzkowitz said.

The study did not receive any funding. Macaron and Itzkowitz reported no competing interests.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

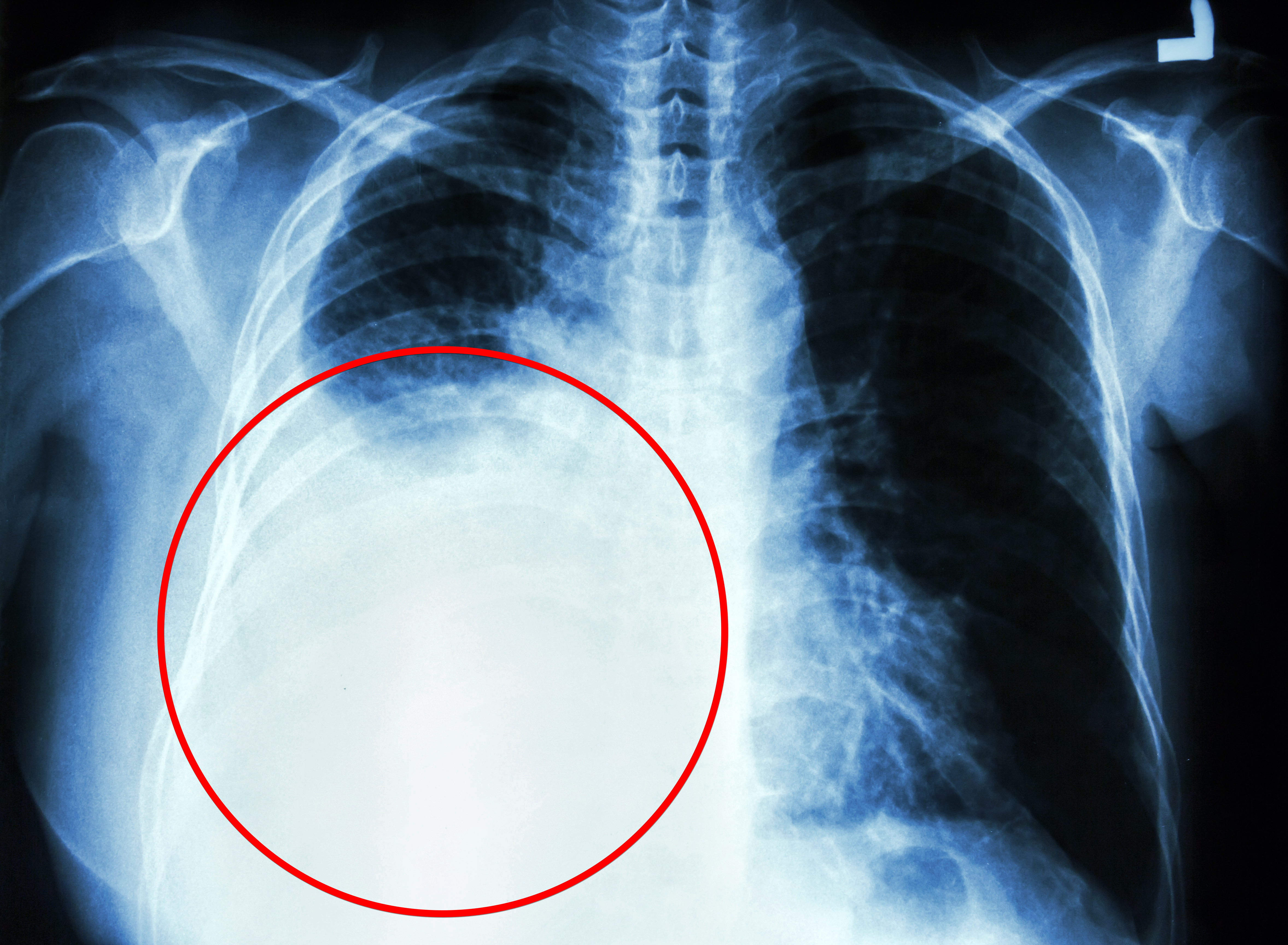

A ‘Fool’s Errand’? Picking a Winner for Treating Early-Stage NSCLC

For years, the default definitive treatment for patients with early-stage I non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been surgical resection, typically minimally invasive lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the European Society for Medical Oncology all list surgery (in particular, lobectomy) as the primary local therapy for fit, operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

More recently, however, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), also called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, has emerged as a definitive treatment option for stage I NSCLC, especially for older, less fit patients who are unsuitable or deemed high-risk for surgery.

“We see patients in our practice who cannot undergo surgery or who may not have adequate lung function to be able to tolerate surgery, and for these patients who are medically inoperable or surgically unresectable, radiation therapy may be a reasonable option,” Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, professor and lung cancer specialist, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

Given some encouraging data suggesting that SBRT could provide similar survival outcomes and be an alternative to surgery for operable disease, SBRT is also increasingly being considered in these early-stage patients. However, other evidence indicates that SBRT may be associated with higher rates of regional and distant recurrences and worse long-term survival, particularly in operable patients.

What may ultimately matter most is carefully selecting operable patients who undergo SBRT.

Aggarwal has encountered certain patients who are fit for surgery but would rather have radiation therapy. “This is an individual decision, and these patients are usually discussed at tumor board and in multidisciplinary discussions to really make sure that they’re making the right decision for themselves,” she explained.

The Pros and Cons of SBRT

SBRT is a nonsurgical approach in which precision high-dose radiation is delivered in just a few fractions — typically, 3, 5, or 8, depending on institutional protocols and tumor characteristics.

SBRT is performed on an outpatient basis, usually over 1-2 weeks, with most patients able to resume usual activities with minimal to no delay. Surgery, on the other hand, requires a hospital stay and takes most people about 2-6 weeks to return to regular activities. SBRT also avoids anesthesia and surgical incisions, both of which come with risks.

The data on SBRT in early-stage NSCLC are mixed. While some studies indicate that SBRT comes with promising survival outcomes, other research has reported worse survival and recurrence rates.

One potential reason for higher recurrence rates with SBRT is the lack of pathologic nodal staging, which only happens after surgery, as well as lower rates of nodal evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy before surgery or SBRT. Without nodal assessments, clinicians may miss a more aggressive histology or more advanced nodal stage, which would go undertreated if patients received SBRT.

Latest Data in Large Cohort

A recent study published in Lung Cancer indicated that, when carefully selected, operable patients with early NSCLC have comparable survival with lobectomy or SBRT.

In the study, Dutch researchers took an in-depth look at survival and recurrence patterns in a retrospective cohort study of 2183 patients with clinical stage I NSCLC treated with minimally invasive lobectomy or SBRT. The study includes one of the largest cohorts to date, with robust data collection on baseline characteristics, comorbidities, tumor size, performance status, and follow-up.

Patients receiving SBRT were typically older (median age, 74 vs 67 years), had higher comorbidity burdens (Charlson index ≥ 5 in 57% of SBRT patients vs 23% of surgical patients), worse performance status, and lower lung function. To adjust for these differences, the researchers used propensity score weighting so the SBRT group’s baseline characteristics were comparable with those in the surgery group.

The surgery cohort had more invasive nodal evaluation: 21% underwent endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy vs only 12% in the SBRT group. The vast majority in both groups had PET-CT staging, reflecting modern imaging-based workups.

While 5-year local recurrence rates between the two groups were similar (13.1% for SBRT vs 12.1% for surgery), the 5-year regional recurrence rate was significantly higher after SBRT than lobectomy (18.1% vs 14.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), as was the distant metastasis rate (26.2% vs 20.2%; HR, 0.72).

Mortality at 30 days was higher after surgery than SBRT (1.0% vs 0.2%). And in the unadjusted analysis, 5-year overall survival was significantly better with lobectomy than SBRT (70.2% vs 40.3%).

However, when the analysis only included patients with similar baseline characteristics, overall survival was no longer significantly different in the two groups (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.65-1.20). Lung cancer–specific mortality was also not significantly different between the two treatments (HR, 1.08), but the study was underpowered to detect significant differences in this outcome on the basis of a relatively low number of deaths from NSCLC.

Still, even after comparing similar patients, recurrence-free survival was notably better with surgery (HR, 0.70), due to fewer regional recurrences and distant metastases. Overall, 13% of the surgical cohort had nodal upstaging at pathology, meaning that even in clinically “node-negative” stage I disease, a subset of patients had unsuspected nodal involvement.

Patients receiving SBRT did not have pathologic nodal staging, raising the possibility of occult micrometastases. The authors noted that the proportion of SBRT patients with occult lymph node metastases is likely at least equal to that in the surgery group, but these metastases would go undetected without pathologic assessment.

Missing potential occult micrometastases in the SBRT group likely contributed to higher regional recurrence rates over time. By improving nodal staging, more patients with occult lymph node metastases who would be undertreated with SBRT may be identified before treatment, the authors said.

What Do Experts Say?

So, is SBRT an option for patients with stage I NSCLC?

Opinions vary.

“If you got one shot for a cure, then you want to do the surgery because that’s what results in a cure,” said Raja Flores, MD, chairman of Thoracic Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City.

Flores noted that the survival rate with surgery is high in this population. “There’s really nothing out there that can compare,” he said.

In his view, surgery “remains the gold standard.” However, “radiation could be considered in nonsurgical candidates,” he said.

The most recent NCCN guidelines align with Flores’ take. The guidelines say that SBRT is indicated for stage IA-IIA (N0) NSCLC in patients who are deemed “medically inoperable, high surgical risk as determined by thoracic surgeon, and those who decline surgery after thoracic surgical consultation.”

Clifford G. Robinson, MD, agreed. “In the United States, we largely treat patients with SBRT who are medically inoperable or high-risk operable and a much smaller proportion who decline surgery,” said Robinson, professor of radiation oncology and chief of SBRT at Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis. “Many patients who are deemed operable are not offered SBRT.”

Still, for Robinson, determining which patients are best suited for surgery or SBRT remains unclear.

“Retrospective comparisons are fraught with problems because of confounding,” Robinson told this news organization. “That is, the healthier patients get surgery, and the less healthy ones get SBRT. No manner of fancy statistical manipulation can remove that fact.”

In fact, a recent meta-analysis found that the most significant variable predicting whether surgery or SBRT was superior in retrospective studies was whether the author was a surgeon or radiation oncologist.

Robinson noted that multiple randomized trials have attempted to randomize patients with medically operable early-stage NSCLC to surgery or SBRT and failed to accrue, largely due to patients’ “understandable unwillingness to be randomized between operative vs nonoperative interventions when most already prefer one or the other approach.”

Flores highlighted another point of caution about interpreting trial results: Not all early-stage NSCLC behaves similarly. “Some are slow-growing ‘turtles,’ and others are aggressive ‘rabbits’ — and the turtles are usually the ones that have been included in these radiotherapy trials, and that’s the danger,” he said.

While medical operability is the primary factor for deciding the treatment modality for early-stage NSCLC, there are other more subtle factors that can play into the decision.

These include prior surgery or radiotherapy to the chest, prior cancers, and social issues, such as the patient being a primary caregiver for another person and job insecurity, that might make recovery from surgery more challenging. And in rare instances, a patient may be medically fit to undergo surgery, but the cancer is technically challenging to resect due to anatomic issues or prior surgery to the chest, Robinson added.

A Winner?

Results from two ongoing, highly anticipated randomized trials expected in the next several years will hopefully provide additional insights and clarify ongoing uncertainties about the optimal treatment strategies for operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

STABLE-MATES is comparing outcomes after sublobar resection and SBRT in high-risk operable stage I NSCLC, and VALOR is evaluating outcomes after anatomic pulmonary resections and SBRT in patients with stage I NSCLC who have a long life expectancy and are fit enough to tolerate surgery.

But Robinson said his group believes that trying to decide on a winner is a “fool’s errand” and is instead running a pragmatic study across multiple academic and community centers around the United States and Canada where patients choose therapy based on their personal preferences and guidance from their physicians. The researchers will carefully track baseline comorbidity and frailty and assess serial quality-of-life changes over time.

“The goal is to create a calculator that a given patient might use in the future to determine what patients like them would have received, complete with expected outcomes and side effects,” Robinson said.

Robinson cautioned, however, that it “seems unlikely, given the existing literature, that one of the treatments will be truly ‘superior’ to the other one and lead to the ‘losing’ treatment fading away since both are excellent options with pros and cons.”

Aggarwal, Robinson, and Flores had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For years, the default definitive treatment for patients with early-stage I non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been surgical resection, typically minimally invasive lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the European Society for Medical Oncology all list surgery (in particular, lobectomy) as the primary local therapy for fit, operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

More recently, however, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), also called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, has emerged as a definitive treatment option for stage I NSCLC, especially for older, less fit patients who are unsuitable or deemed high-risk for surgery.

“We see patients in our practice who cannot undergo surgery or who may not have adequate lung function to be able to tolerate surgery, and for these patients who are medically inoperable or surgically unresectable, radiation therapy may be a reasonable option,” Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, professor and lung cancer specialist, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

Given some encouraging data suggesting that SBRT could provide similar survival outcomes and be an alternative to surgery for operable disease, SBRT is also increasingly being considered in these early-stage patients. However, other evidence indicates that SBRT may be associated with higher rates of regional and distant recurrences and worse long-term survival, particularly in operable patients.

What may ultimately matter most is carefully selecting operable patients who undergo SBRT.

Aggarwal has encountered certain patients who are fit for surgery but would rather have radiation therapy. “This is an individual decision, and these patients are usually discussed at tumor board and in multidisciplinary discussions to really make sure that they’re making the right decision for themselves,” she explained.

The Pros and Cons of SBRT

SBRT is a nonsurgical approach in which precision high-dose radiation is delivered in just a few fractions — typically, 3, 5, or 8, depending on institutional protocols and tumor characteristics.

SBRT is performed on an outpatient basis, usually over 1-2 weeks, with most patients able to resume usual activities with minimal to no delay. Surgery, on the other hand, requires a hospital stay and takes most people about 2-6 weeks to return to regular activities. SBRT also avoids anesthesia and surgical incisions, both of which come with risks.

The data on SBRT in early-stage NSCLC are mixed. While some studies indicate that SBRT comes with promising survival outcomes, other research has reported worse survival and recurrence rates.

One potential reason for higher recurrence rates with SBRT is the lack of pathologic nodal staging, which only happens after surgery, as well as lower rates of nodal evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy before surgery or SBRT. Without nodal assessments, clinicians may miss a more aggressive histology or more advanced nodal stage, which would go undertreated if patients received SBRT.

Latest Data in Large Cohort

A recent study published in Lung Cancer indicated that, when carefully selected, operable patients with early NSCLC have comparable survival with lobectomy or SBRT.

In the study, Dutch researchers took an in-depth look at survival and recurrence patterns in a retrospective cohort study of 2183 patients with clinical stage I NSCLC treated with minimally invasive lobectomy or SBRT. The study includes one of the largest cohorts to date, with robust data collection on baseline characteristics, comorbidities, tumor size, performance status, and follow-up.

Patients receiving SBRT were typically older (median age, 74 vs 67 years), had higher comorbidity burdens (Charlson index ≥ 5 in 57% of SBRT patients vs 23% of surgical patients), worse performance status, and lower lung function. To adjust for these differences, the researchers used propensity score weighting so the SBRT group’s baseline characteristics were comparable with those in the surgery group.

The surgery cohort had more invasive nodal evaluation: 21% underwent endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy vs only 12% in the SBRT group. The vast majority in both groups had PET-CT staging, reflecting modern imaging-based workups.

While 5-year local recurrence rates between the two groups were similar (13.1% for SBRT vs 12.1% for surgery), the 5-year regional recurrence rate was significantly higher after SBRT than lobectomy (18.1% vs 14.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), as was the distant metastasis rate (26.2% vs 20.2%; HR, 0.72).

Mortality at 30 days was higher after surgery than SBRT (1.0% vs 0.2%). And in the unadjusted analysis, 5-year overall survival was significantly better with lobectomy than SBRT (70.2% vs 40.3%).

However, when the analysis only included patients with similar baseline characteristics, overall survival was no longer significantly different in the two groups (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.65-1.20). Lung cancer–specific mortality was also not significantly different between the two treatments (HR, 1.08), but the study was underpowered to detect significant differences in this outcome on the basis of a relatively low number of deaths from NSCLC.

Still, even after comparing similar patients, recurrence-free survival was notably better with surgery (HR, 0.70), due to fewer regional recurrences and distant metastases. Overall, 13% of the surgical cohort had nodal upstaging at pathology, meaning that even in clinically “node-negative” stage I disease, a subset of patients had unsuspected nodal involvement.

Patients receiving SBRT did not have pathologic nodal staging, raising the possibility of occult micrometastases. The authors noted that the proportion of SBRT patients with occult lymph node metastases is likely at least equal to that in the surgery group, but these metastases would go undetected without pathologic assessment.

Missing potential occult micrometastases in the SBRT group likely contributed to higher regional recurrence rates over time. By improving nodal staging, more patients with occult lymph node metastases who would be undertreated with SBRT may be identified before treatment, the authors said.

What Do Experts Say?

So, is SBRT an option for patients with stage I NSCLC?

Opinions vary.

“If you got one shot for a cure, then you want to do the surgery because that’s what results in a cure,” said Raja Flores, MD, chairman of Thoracic Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City.

Flores noted that the survival rate with surgery is high in this population. “There’s really nothing out there that can compare,” he said.

In his view, surgery “remains the gold standard.” However, “radiation could be considered in nonsurgical candidates,” he said.

The most recent NCCN guidelines align with Flores’ take. The guidelines say that SBRT is indicated for stage IA-IIA (N0) NSCLC in patients who are deemed “medically inoperable, high surgical risk as determined by thoracic surgeon, and those who decline surgery after thoracic surgical consultation.”

Clifford G. Robinson, MD, agreed. “In the United States, we largely treat patients with SBRT who are medically inoperable or high-risk operable and a much smaller proportion who decline surgery,” said Robinson, professor of radiation oncology and chief of SBRT at Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis. “Many patients who are deemed operable are not offered SBRT.”

Still, for Robinson, determining which patients are best suited for surgery or SBRT remains unclear.

“Retrospective comparisons are fraught with problems because of confounding,” Robinson told this news organization. “That is, the healthier patients get surgery, and the less healthy ones get SBRT. No manner of fancy statistical manipulation can remove that fact.”

In fact, a recent meta-analysis found that the most significant variable predicting whether surgery or SBRT was superior in retrospective studies was whether the author was a surgeon or radiation oncologist.

Robinson noted that multiple randomized trials have attempted to randomize patients with medically operable early-stage NSCLC to surgery or SBRT and failed to accrue, largely due to patients’ “understandable unwillingness to be randomized between operative vs nonoperative interventions when most already prefer one or the other approach.”

Flores highlighted another point of caution about interpreting trial results: Not all early-stage NSCLC behaves similarly. “Some are slow-growing ‘turtles,’ and others are aggressive ‘rabbits’ — and the turtles are usually the ones that have been included in these radiotherapy trials, and that’s the danger,” he said.

While medical operability is the primary factor for deciding the treatment modality for early-stage NSCLC, there are other more subtle factors that can play into the decision.

These include prior surgery or radiotherapy to the chest, prior cancers, and social issues, such as the patient being a primary caregiver for another person and job insecurity, that might make recovery from surgery more challenging. And in rare instances, a patient may be medically fit to undergo surgery, but the cancer is technically challenging to resect due to anatomic issues or prior surgery to the chest, Robinson added.

A Winner?

Results from two ongoing, highly anticipated randomized trials expected in the next several years will hopefully provide additional insights and clarify ongoing uncertainties about the optimal treatment strategies for operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

STABLE-MATES is comparing outcomes after sublobar resection and SBRT in high-risk operable stage I NSCLC, and VALOR is evaluating outcomes after anatomic pulmonary resections and SBRT in patients with stage I NSCLC who have a long life expectancy and are fit enough to tolerate surgery.

But Robinson said his group believes that trying to decide on a winner is a “fool’s errand” and is instead running a pragmatic study across multiple academic and community centers around the United States and Canada where patients choose therapy based on their personal preferences and guidance from their physicians. The researchers will carefully track baseline comorbidity and frailty and assess serial quality-of-life changes over time.

“The goal is to create a calculator that a given patient might use in the future to determine what patients like them would have received, complete with expected outcomes and side effects,” Robinson said.

Robinson cautioned, however, that it “seems unlikely, given the existing literature, that one of the treatments will be truly ‘superior’ to the other one and lead to the ‘losing’ treatment fading away since both are excellent options with pros and cons.”

Aggarwal, Robinson, and Flores had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For years, the default definitive treatment for patients with early-stage I non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been surgical resection, typically minimally invasive lobectomy with systematic lymph node dissection.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the European Society for Medical Oncology all list surgery (in particular, lobectomy) as the primary local therapy for fit, operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

More recently, however, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), also called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, has emerged as a definitive treatment option for stage I NSCLC, especially for older, less fit patients who are unsuitable or deemed high-risk for surgery.

“We see patients in our practice who cannot undergo surgery or who may not have adequate lung function to be able to tolerate surgery, and for these patients who are medically inoperable or surgically unresectable, radiation therapy may be a reasonable option,” Charu Aggarwal, MD, MPH, professor and lung cancer specialist, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

Given some encouraging data suggesting that SBRT could provide similar survival outcomes and be an alternative to surgery for operable disease, SBRT is also increasingly being considered in these early-stage patients. However, other evidence indicates that SBRT may be associated with higher rates of regional and distant recurrences and worse long-term survival, particularly in operable patients.

What may ultimately matter most is carefully selecting operable patients who undergo SBRT.

Aggarwal has encountered certain patients who are fit for surgery but would rather have radiation therapy. “This is an individual decision, and these patients are usually discussed at tumor board and in multidisciplinary discussions to really make sure that they’re making the right decision for themselves,” she explained.

The Pros and Cons of SBRT

SBRT is a nonsurgical approach in which precision high-dose radiation is delivered in just a few fractions — typically, 3, 5, or 8, depending on institutional protocols and tumor characteristics.

SBRT is performed on an outpatient basis, usually over 1-2 weeks, with most patients able to resume usual activities with minimal to no delay. Surgery, on the other hand, requires a hospital stay and takes most people about 2-6 weeks to return to regular activities. SBRT also avoids anesthesia and surgical incisions, both of which come with risks.

The data on SBRT in early-stage NSCLC are mixed. While some studies indicate that SBRT comes with promising survival outcomes, other research has reported worse survival and recurrence rates.

One potential reason for higher recurrence rates with SBRT is the lack of pathologic nodal staging, which only happens after surgery, as well as lower rates of nodal evaluation with endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy before surgery or SBRT. Without nodal assessments, clinicians may miss a more aggressive histology or more advanced nodal stage, which would go undertreated if patients received SBRT.

Latest Data in Large Cohort

A recent study published in Lung Cancer indicated that, when carefully selected, operable patients with early NSCLC have comparable survival with lobectomy or SBRT.

In the study, Dutch researchers took an in-depth look at survival and recurrence patterns in a retrospective cohort study of 2183 patients with clinical stage I NSCLC treated with minimally invasive lobectomy or SBRT. The study includes one of the largest cohorts to date, with robust data collection on baseline characteristics, comorbidities, tumor size, performance status, and follow-up.

Patients receiving SBRT were typically older (median age, 74 vs 67 years), had higher comorbidity burdens (Charlson index ≥ 5 in 57% of SBRT patients vs 23% of surgical patients), worse performance status, and lower lung function. To adjust for these differences, the researchers used propensity score weighting so the SBRT group’s baseline characteristics were comparable with those in the surgery group.

The surgery cohort had more invasive nodal evaluation: 21% underwent endobronchial ultrasound or mediastinoscopy vs only 12% in the SBRT group. The vast majority in both groups had PET-CT staging, reflecting modern imaging-based workups.

While 5-year local recurrence rates between the two groups were similar (13.1% for SBRT vs 12.1% for surgery), the 5-year regional recurrence rate was significantly higher after SBRT than lobectomy (18.1% vs 14.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.74), as was the distant metastasis rate (26.2% vs 20.2%; HR, 0.72).

Mortality at 30 days was higher after surgery than SBRT (1.0% vs 0.2%). And in the unadjusted analysis, 5-year overall survival was significantly better with lobectomy than SBRT (70.2% vs 40.3%).

However, when the analysis only included patients with similar baseline characteristics, overall survival was no longer significantly different in the two groups (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.65-1.20). Lung cancer–specific mortality was also not significantly different between the two treatments (HR, 1.08), but the study was underpowered to detect significant differences in this outcome on the basis of a relatively low number of deaths from NSCLC.

Still, even after comparing similar patients, recurrence-free survival was notably better with surgery (HR, 0.70), due to fewer regional recurrences and distant metastases. Overall, 13% of the surgical cohort had nodal upstaging at pathology, meaning that even in clinically “node-negative” stage I disease, a subset of patients had unsuspected nodal involvement.

Patients receiving SBRT did not have pathologic nodal staging, raising the possibility of occult micrometastases. The authors noted that the proportion of SBRT patients with occult lymph node metastases is likely at least equal to that in the surgery group, but these metastases would go undetected without pathologic assessment.

Missing potential occult micrometastases in the SBRT group likely contributed to higher regional recurrence rates over time. By improving nodal staging, more patients with occult lymph node metastases who would be undertreated with SBRT may be identified before treatment, the authors said.

What Do Experts Say?

So, is SBRT an option for patients with stage I NSCLC?

Opinions vary.

“If you got one shot for a cure, then you want to do the surgery because that’s what results in a cure,” said Raja Flores, MD, chairman of Thoracic Surgery, Mount Sinai Health System, New York City.

Flores noted that the survival rate with surgery is high in this population. “There’s really nothing out there that can compare,” he said.

In his view, surgery “remains the gold standard.” However, “radiation could be considered in nonsurgical candidates,” he said.

The most recent NCCN guidelines align with Flores’ take. The guidelines say that SBRT is indicated for stage IA-IIA (N0) NSCLC in patients who are deemed “medically inoperable, high surgical risk as determined by thoracic surgeon, and those who decline surgery after thoracic surgical consultation.”

Clifford G. Robinson, MD, agreed. “In the United States, we largely treat patients with SBRT who are medically inoperable or high-risk operable and a much smaller proportion who decline surgery,” said Robinson, professor of radiation oncology and chief of SBRT at Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis. “Many patients who are deemed operable are not offered SBRT.”

Still, for Robinson, determining which patients are best suited for surgery or SBRT remains unclear.

“Retrospective comparisons are fraught with problems because of confounding,” Robinson told this news organization. “That is, the healthier patients get surgery, and the less healthy ones get SBRT. No manner of fancy statistical manipulation can remove that fact.”

In fact, a recent meta-analysis found that the most significant variable predicting whether surgery or SBRT was superior in retrospective studies was whether the author was a surgeon or radiation oncologist.

Robinson noted that multiple randomized trials have attempted to randomize patients with medically operable early-stage NSCLC to surgery or SBRT and failed to accrue, largely due to patients’ “understandable unwillingness to be randomized between operative vs nonoperative interventions when most already prefer one or the other approach.”

Flores highlighted another point of caution about interpreting trial results: Not all early-stage NSCLC behaves similarly. “Some are slow-growing ‘turtles,’ and others are aggressive ‘rabbits’ — and the turtles are usually the ones that have been included in these radiotherapy trials, and that’s the danger,” he said.

While medical operability is the primary factor for deciding the treatment modality for early-stage NSCLC, there are other more subtle factors that can play into the decision.

These include prior surgery or radiotherapy to the chest, prior cancers, and social issues, such as the patient being a primary caregiver for another person and job insecurity, that might make recovery from surgery more challenging. And in rare instances, a patient may be medically fit to undergo surgery, but the cancer is technically challenging to resect due to anatomic issues or prior surgery to the chest, Robinson added.

A Winner?

Results from two ongoing, highly anticipated randomized trials expected in the next several years will hopefully provide additional insights and clarify ongoing uncertainties about the optimal treatment strategies for operable patients with stage I NSCLC.

STABLE-MATES is comparing outcomes after sublobar resection and SBRT in high-risk operable stage I NSCLC, and VALOR is evaluating outcomes after anatomic pulmonary resections and SBRT in patients with stage I NSCLC who have a long life expectancy and are fit enough to tolerate surgery.

But Robinson said his group believes that trying to decide on a winner is a “fool’s errand” and is instead running a pragmatic study across multiple academic and community centers around the United States and Canada where patients choose therapy based on their personal preferences and guidance from their physicians. The researchers will carefully track baseline comorbidity and frailty and assess serial quality-of-life changes over time.

“The goal is to create a calculator that a given patient might use in the future to determine what patients like them would have received, complete with expected outcomes and side effects,” Robinson said.

Robinson cautioned, however, that it “seems unlikely, given the existing literature, that one of the treatments will be truly ‘superior’ to the other one and lead to the ‘losing’ treatment fading away since both are excellent options with pros and cons.”

Aggarwal, Robinson, and Flores had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA OKs Guselkumab for Crohn’s Disease

The approval marks the fourth indication for guselkumab, which was approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2017, active psoriatic arthritis in 2020, and moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in 2024.