User login

Resistant TB: Adjustments to BPaL regimen reduce AEs, not efficacy

Lower doses of linezolid in the BPaL drug regimen (bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid) significantly reduce the adverse events associated with the treatment for patients with highly drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) without compromising its high efficacy, new research shows.

“The ZeNix trial shows that reduced doses and/or shorter durations of linezolid appear to have high efficacy and improved safety,” said first author Francesca Conradie, MB, BCh, of the clinical HIV research unit, faculty of health sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, in presenting the findings at the virtual meeting of the International AIDS Society conference.

As recently reported in the pivotal Nix-TB trial, the BPaL regimen yielded a 90% treatment success rate among people with highly drug-resistant forms of TB.

However, a 6-month regimen that included linezolid 1,200 mg resulted in toxic effects: 81% of patients in the study experienced peripheral neuropathy, and myelosuppression occurred in 48%. These effects often led to dose reductions or treatment interruption.

Adjustments in the dose of linezolid in the new ZeNix trial substantially reduced peripheral neuropathy to 13% and myelosuppression to 7%, with no significant reduction in the treatment response.

Importantly, the results were similar among patients with and those without HIV. This is of note because TB is the leading cause of death among patients with HIV.

“In the ZeNix trial, only 20% of patients were HIV infected, but in the [previous] Nix-TB trial, 30% were infected, so we have experience now in about 70 patients who were infected, and the outcomes were no different,” Dr. Conradie said in an interview.

Experts say the findings represent an important turn in the steep challenge of tackling highly resistant TB.

“In our opinion, these are exciting results that could change treatment guidelines for highly drug-resistant tuberculosis, with real benefits for the patients,” said Hendrik Streeck, MD, International AIDS Society cochair and director of the Institute of Virology and the Institute for HIV Research at the University Bonn (Germany), in a press conference.

Payam Nahid, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Tuberculosis at theUniversity of California, San Francisco, agreed.

“The results of this trial will impact global practices in treating drug-resistant TB as well as the design and conduct of future TB clinical trials,” Dr. Nahid said in an interview.

ZeNix trial

The phase 3 ZeNix trial included 181 patients with highly resistant TB in South Africa, Russia, Georgia, and Moldova. The mean age of the patients was 37 years; 67.4% were men, 63.5% were White, and 19.9% were HIV positive.

All patients were treated for 6 months with bedaquiline 200 mg daily for 8 weeks followed by 100 mg daily for 18 weeks, as well as pretomanid 200 mg daily.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive one of four daily doses of linezolid: 1,200 mg for 6 months (the original dose from the Nix-TB trial; n = 45) or 2 months (n = 46), or 600 mg for 6 or 2 months (45 patients each).

Percentages of patients with HIV were equal among the four groups, at about 20% each.

The primary outcomes – resolution of clinical disease and a negative culture status after 6 months – were observed across all linezolid dose groups. The success rate was 93% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 6 months, 89% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 2 months, 91% for those receiving 600 mg for 6 months, and 84% for those receiving 600 mg for 2 months.

With regard to the key adverse events of peripheral neuropathy and myelosuppression, manifested as anemia, the highest rates were among those who received linezolid 1,200 mg for 6 month, at 38% and 22%, respectively, compared with 24% and 17.4% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months, 24% and 2% among those who received 600 mg for 6 months, and 13% and 6.7% among those who received 600 mg for 2 months.

Four cases of optic neuropathy occurred among those who received 1,200 mg for 6 months; all cases resolved.

Patients who received 1,200 mg for 6 months required the highest number of linezolid dose modifications; 51% required changes that included reduction, interruption, or discontinuation, compared with 28% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months and 13% each in the other two groups.

On the basis of these results, “my personal opinion is that 600 mg at 6 months [of linezolid] is most likely the best strategy for the treatment of this highly resistant treatment population group,” Dr. Conradie told this news organization.

Findings represent ‘great news’ in addressing concerns

Dr. Nahid further commented that the results are highly encouraging in light of the ongoing concerns about the effects of linezolid in the BPaL regimen.

“This is great news,” he said. “The ZeNix trial addresses a key concern that providers and patients have had regarding the safety and tolerability of taking 6 months of linezolid at 1200 mg/d as part of the BPaL regimen.

“The findings that doses lower and durations shorter than the current 1,200 mg linezolid daily for 6 months will significantly expand the usability of the BPaL regimen worldwide.”

The inclusion of patients with HIV was essential in the trial, he noted.

“There are drug-drug interactions to be considered, among other factors that impact drug exposure,” Dr. Nahid said.

“Inclusion of patients living with HIV in this study means that any modifications to the BPaL regimen considered by the WHO [World Health Organization] and other policy decision makers will include data from this key population,” he said. “Of course, more data are needed on safety, tolerability, and efficacy on BPaL in general, and there are international cohorts and demonstration projects underway that will enhance our understanding of the regimen in HIV and in other special populations.”

The authors, Dr. Streeck, and Dr. Nahid have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was updated 7/21/21.

Lower doses of linezolid in the BPaL drug regimen (bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid) significantly reduce the adverse events associated with the treatment for patients with highly drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) without compromising its high efficacy, new research shows.

“The ZeNix trial shows that reduced doses and/or shorter durations of linezolid appear to have high efficacy and improved safety,” said first author Francesca Conradie, MB, BCh, of the clinical HIV research unit, faculty of health sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, in presenting the findings at the virtual meeting of the International AIDS Society conference.

As recently reported in the pivotal Nix-TB trial, the BPaL regimen yielded a 90% treatment success rate among people with highly drug-resistant forms of TB.

However, a 6-month regimen that included linezolid 1,200 mg resulted in toxic effects: 81% of patients in the study experienced peripheral neuropathy, and myelosuppression occurred in 48%. These effects often led to dose reductions or treatment interruption.

Adjustments in the dose of linezolid in the new ZeNix trial substantially reduced peripheral neuropathy to 13% and myelosuppression to 7%, with no significant reduction in the treatment response.

Importantly, the results were similar among patients with and those without HIV. This is of note because TB is the leading cause of death among patients with HIV.

“In the ZeNix trial, only 20% of patients were HIV infected, but in the [previous] Nix-TB trial, 30% were infected, so we have experience now in about 70 patients who were infected, and the outcomes were no different,” Dr. Conradie said in an interview.

Experts say the findings represent an important turn in the steep challenge of tackling highly resistant TB.

“In our opinion, these are exciting results that could change treatment guidelines for highly drug-resistant tuberculosis, with real benefits for the patients,” said Hendrik Streeck, MD, International AIDS Society cochair and director of the Institute of Virology and the Institute for HIV Research at the University Bonn (Germany), in a press conference.

Payam Nahid, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Tuberculosis at theUniversity of California, San Francisco, agreed.

“The results of this trial will impact global practices in treating drug-resistant TB as well as the design and conduct of future TB clinical trials,” Dr. Nahid said in an interview.

ZeNix trial

The phase 3 ZeNix trial included 181 patients with highly resistant TB in South Africa, Russia, Georgia, and Moldova. The mean age of the patients was 37 years; 67.4% were men, 63.5% were White, and 19.9% were HIV positive.

All patients were treated for 6 months with bedaquiline 200 mg daily for 8 weeks followed by 100 mg daily for 18 weeks, as well as pretomanid 200 mg daily.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive one of four daily doses of linezolid: 1,200 mg for 6 months (the original dose from the Nix-TB trial; n = 45) or 2 months (n = 46), or 600 mg for 6 or 2 months (45 patients each).

Percentages of patients with HIV were equal among the four groups, at about 20% each.

The primary outcomes – resolution of clinical disease and a negative culture status after 6 months – were observed across all linezolid dose groups. The success rate was 93% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 6 months, 89% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 2 months, 91% for those receiving 600 mg for 6 months, and 84% for those receiving 600 mg for 2 months.

With regard to the key adverse events of peripheral neuropathy and myelosuppression, manifested as anemia, the highest rates were among those who received linezolid 1,200 mg for 6 month, at 38% and 22%, respectively, compared with 24% and 17.4% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months, 24% and 2% among those who received 600 mg for 6 months, and 13% and 6.7% among those who received 600 mg for 2 months.

Four cases of optic neuropathy occurred among those who received 1,200 mg for 6 months; all cases resolved.

Patients who received 1,200 mg for 6 months required the highest number of linezolid dose modifications; 51% required changes that included reduction, interruption, or discontinuation, compared with 28% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months and 13% each in the other two groups.

On the basis of these results, “my personal opinion is that 600 mg at 6 months [of linezolid] is most likely the best strategy for the treatment of this highly resistant treatment population group,” Dr. Conradie told this news organization.

Findings represent ‘great news’ in addressing concerns

Dr. Nahid further commented that the results are highly encouraging in light of the ongoing concerns about the effects of linezolid in the BPaL regimen.

“This is great news,” he said. “The ZeNix trial addresses a key concern that providers and patients have had regarding the safety and tolerability of taking 6 months of linezolid at 1200 mg/d as part of the BPaL regimen.

“The findings that doses lower and durations shorter than the current 1,200 mg linezolid daily for 6 months will significantly expand the usability of the BPaL regimen worldwide.”

The inclusion of patients with HIV was essential in the trial, he noted.

“There are drug-drug interactions to be considered, among other factors that impact drug exposure,” Dr. Nahid said.

“Inclusion of patients living with HIV in this study means that any modifications to the BPaL regimen considered by the WHO [World Health Organization] and other policy decision makers will include data from this key population,” he said. “Of course, more data are needed on safety, tolerability, and efficacy on BPaL in general, and there are international cohorts and demonstration projects underway that will enhance our understanding of the regimen in HIV and in other special populations.”

The authors, Dr. Streeck, and Dr. Nahid have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was updated 7/21/21.

Lower doses of linezolid in the BPaL drug regimen (bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid) significantly reduce the adverse events associated with the treatment for patients with highly drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) without compromising its high efficacy, new research shows.

“The ZeNix trial shows that reduced doses and/or shorter durations of linezolid appear to have high efficacy and improved safety,” said first author Francesca Conradie, MB, BCh, of the clinical HIV research unit, faculty of health sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, in presenting the findings at the virtual meeting of the International AIDS Society conference.

As recently reported in the pivotal Nix-TB trial, the BPaL regimen yielded a 90% treatment success rate among people with highly drug-resistant forms of TB.

However, a 6-month regimen that included linezolid 1,200 mg resulted in toxic effects: 81% of patients in the study experienced peripheral neuropathy, and myelosuppression occurred in 48%. These effects often led to dose reductions or treatment interruption.

Adjustments in the dose of linezolid in the new ZeNix trial substantially reduced peripheral neuropathy to 13% and myelosuppression to 7%, with no significant reduction in the treatment response.

Importantly, the results were similar among patients with and those without HIV. This is of note because TB is the leading cause of death among patients with HIV.

“In the ZeNix trial, only 20% of patients were HIV infected, but in the [previous] Nix-TB trial, 30% were infected, so we have experience now in about 70 patients who were infected, and the outcomes were no different,” Dr. Conradie said in an interview.

Experts say the findings represent an important turn in the steep challenge of tackling highly resistant TB.

“In our opinion, these are exciting results that could change treatment guidelines for highly drug-resistant tuberculosis, with real benefits for the patients,” said Hendrik Streeck, MD, International AIDS Society cochair and director of the Institute of Virology and the Institute for HIV Research at the University Bonn (Germany), in a press conference.

Payam Nahid, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Tuberculosis at theUniversity of California, San Francisco, agreed.

“The results of this trial will impact global practices in treating drug-resistant TB as well as the design and conduct of future TB clinical trials,” Dr. Nahid said in an interview.

ZeNix trial

The phase 3 ZeNix trial included 181 patients with highly resistant TB in South Africa, Russia, Georgia, and Moldova. The mean age of the patients was 37 years; 67.4% were men, 63.5% were White, and 19.9% were HIV positive.

All patients were treated for 6 months with bedaquiline 200 mg daily for 8 weeks followed by 100 mg daily for 18 weeks, as well as pretomanid 200 mg daily.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive one of four daily doses of linezolid: 1,200 mg for 6 months (the original dose from the Nix-TB trial; n = 45) or 2 months (n = 46), or 600 mg for 6 or 2 months (45 patients each).

Percentages of patients with HIV were equal among the four groups, at about 20% each.

The primary outcomes – resolution of clinical disease and a negative culture status after 6 months – were observed across all linezolid dose groups. The success rate was 93% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 6 months, 89% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 2 months, 91% for those receiving 600 mg for 6 months, and 84% for those receiving 600 mg for 2 months.

With regard to the key adverse events of peripheral neuropathy and myelosuppression, manifested as anemia, the highest rates were among those who received linezolid 1,200 mg for 6 month, at 38% and 22%, respectively, compared with 24% and 17.4% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months, 24% and 2% among those who received 600 mg for 6 months, and 13% and 6.7% among those who received 600 mg for 2 months.

Four cases of optic neuropathy occurred among those who received 1,200 mg for 6 months; all cases resolved.

Patients who received 1,200 mg for 6 months required the highest number of linezolid dose modifications; 51% required changes that included reduction, interruption, or discontinuation, compared with 28% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months and 13% each in the other two groups.

On the basis of these results, “my personal opinion is that 600 mg at 6 months [of linezolid] is most likely the best strategy for the treatment of this highly resistant treatment population group,” Dr. Conradie told this news organization.

Findings represent ‘great news’ in addressing concerns

Dr. Nahid further commented that the results are highly encouraging in light of the ongoing concerns about the effects of linezolid in the BPaL regimen.

“This is great news,” he said. “The ZeNix trial addresses a key concern that providers and patients have had regarding the safety and tolerability of taking 6 months of linezolid at 1200 mg/d as part of the BPaL regimen.

“The findings that doses lower and durations shorter than the current 1,200 mg linezolid daily for 6 months will significantly expand the usability of the BPaL regimen worldwide.”

The inclusion of patients with HIV was essential in the trial, he noted.

“There are drug-drug interactions to be considered, among other factors that impact drug exposure,” Dr. Nahid said.

“Inclusion of patients living with HIV in this study means that any modifications to the BPaL regimen considered by the WHO [World Health Organization] and other policy decision makers will include data from this key population,” he said. “Of course, more data are needed on safety, tolerability, and efficacy on BPaL in general, and there are international cohorts and demonstration projects underway that will enhance our understanding of the regimen in HIV and in other special populations.”

The authors, Dr. Streeck, and Dr. Nahid have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was updated 7/21/21.

FROM IAS 2021

Recent trend: Melanoma mortality declining rapidly

according to an annual report by several national organizations.

“Death rates for cutaneous melanoma have declined rapidly in recent years following introduction of new therapies, including targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitors, the first of which was approved by the [Food and Drug Administration] in early 2011,” Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, and associates wrote in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The American Cancer Society, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, issue a joint report each year to update the incidence and mortality of the most common cancers and analyze short- and long-term trends since 2001.

Long-term melanoma mortality gets divided into two trends: First a slow decline over about a decade, then an accelerated decline until the end of the study period, although the timing is slightly different between males and females. For men, the death rate fell by an average of 0.9% a year from 2001 to 2009, compared with 5.7% per year in 2013-2018. For women, the average annual change went from –0.3% for 2001-2012 to –4.4% in 2012-2018.

The incidence of melanoma, however, headed in the opposite direction, rising 1.9% per year for females and 2.2% for males from 2001 to 2017, without the notable change in trend seen with death rates, Dr. Islami and associates said.

Incidence by race/ethnicity, reported for 2013-2017, shows that melanoma is much more common among white non-Hispanics: 37.4 per 100,000 standard population for males and 24.5 for females. Non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives were next at 10.8 (men) and 6.7 (women), followed by Hispanics (5.1/4.5), non-Hispanic Asians/Pacific Islanders (1.6/1.3), and non-Hispanic Blacks (1.2/1.0), they reported.

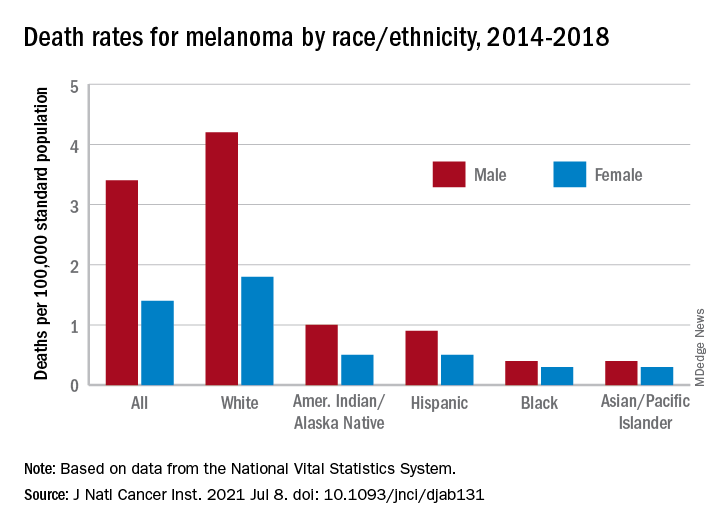

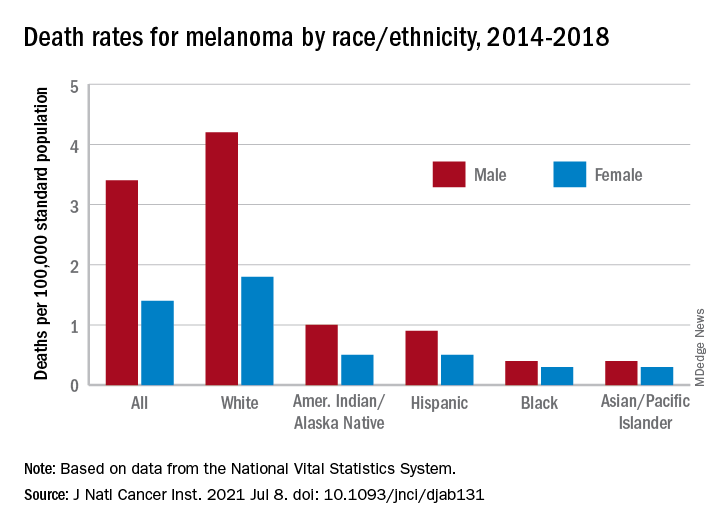

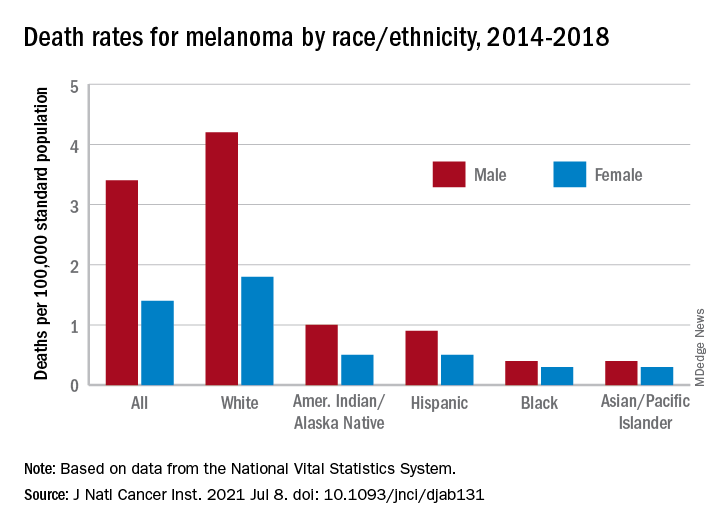

Death rates for melanoma, reported for 2014-2018, follow a similar pattern. White males (4.2 per 100,000) and females (1.8 per 100,000) had the highest mortality, then American Indians/Alaska Natives (1.0/0.5) and Hispanics (0.9/0.5), but rates were the same for Blacks and Asians/Pacific Islanders (0.4/0.3), the investigators said.

The accelerated decline in death rates in more recent years reflects “a substantial increase in survival for metastatic melanoma,” the participating organizations noted in a joint statement.

Increases in 2-year survival in distant-stage disease averaged 3.1% per year for those diagnosed during 2009-2014, which “slightly preceded the FDA approval of new therapies, likely because of the administration of these therapies through clinical trials and the FDA expanded access programs prior to the approval,” Dr. Islami and associates wrote.

The 2-year relative survival for those with nonmetastatic melanoma also improved over the study period, but the increases were much smaller: 0.4% per year for regional-stage disease and just 0.03% localized-stage cases diagnosed in 2001-2014, they reported.

The report was funded by the four participating groups. Six of the 12 investigators are employees of the American Cancer Society whose salaries are solely paid by the society; the other authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

according to an annual report by several national organizations.

“Death rates for cutaneous melanoma have declined rapidly in recent years following introduction of new therapies, including targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitors, the first of which was approved by the [Food and Drug Administration] in early 2011,” Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, and associates wrote in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The American Cancer Society, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, issue a joint report each year to update the incidence and mortality of the most common cancers and analyze short- and long-term trends since 2001.

Long-term melanoma mortality gets divided into two trends: First a slow decline over about a decade, then an accelerated decline until the end of the study period, although the timing is slightly different between males and females. For men, the death rate fell by an average of 0.9% a year from 2001 to 2009, compared with 5.7% per year in 2013-2018. For women, the average annual change went from –0.3% for 2001-2012 to –4.4% in 2012-2018.

The incidence of melanoma, however, headed in the opposite direction, rising 1.9% per year for females and 2.2% for males from 2001 to 2017, without the notable change in trend seen with death rates, Dr. Islami and associates said.

Incidence by race/ethnicity, reported for 2013-2017, shows that melanoma is much more common among white non-Hispanics: 37.4 per 100,000 standard population for males and 24.5 for females. Non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives were next at 10.8 (men) and 6.7 (women), followed by Hispanics (5.1/4.5), non-Hispanic Asians/Pacific Islanders (1.6/1.3), and non-Hispanic Blacks (1.2/1.0), they reported.

Death rates for melanoma, reported for 2014-2018, follow a similar pattern. White males (4.2 per 100,000) and females (1.8 per 100,000) had the highest mortality, then American Indians/Alaska Natives (1.0/0.5) and Hispanics (0.9/0.5), but rates were the same for Blacks and Asians/Pacific Islanders (0.4/0.3), the investigators said.

The accelerated decline in death rates in more recent years reflects “a substantial increase in survival for metastatic melanoma,” the participating organizations noted in a joint statement.

Increases in 2-year survival in distant-stage disease averaged 3.1% per year for those diagnosed during 2009-2014, which “slightly preceded the FDA approval of new therapies, likely because of the administration of these therapies through clinical trials and the FDA expanded access programs prior to the approval,” Dr. Islami and associates wrote.

The 2-year relative survival for those with nonmetastatic melanoma also improved over the study period, but the increases were much smaller: 0.4% per year for regional-stage disease and just 0.03% localized-stage cases diagnosed in 2001-2014, they reported.

The report was funded by the four participating groups. Six of the 12 investigators are employees of the American Cancer Society whose salaries are solely paid by the society; the other authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

according to an annual report by several national organizations.

“Death rates for cutaneous melanoma have declined rapidly in recent years following introduction of new therapies, including targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitors, the first of which was approved by the [Food and Drug Administration] in early 2011,” Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, and associates wrote in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

The American Cancer Society, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Cancer Institute, and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, issue a joint report each year to update the incidence and mortality of the most common cancers and analyze short- and long-term trends since 2001.

Long-term melanoma mortality gets divided into two trends: First a slow decline over about a decade, then an accelerated decline until the end of the study period, although the timing is slightly different between males and females. For men, the death rate fell by an average of 0.9% a year from 2001 to 2009, compared with 5.7% per year in 2013-2018. For women, the average annual change went from –0.3% for 2001-2012 to –4.4% in 2012-2018.

The incidence of melanoma, however, headed in the opposite direction, rising 1.9% per year for females and 2.2% for males from 2001 to 2017, without the notable change in trend seen with death rates, Dr. Islami and associates said.

Incidence by race/ethnicity, reported for 2013-2017, shows that melanoma is much more common among white non-Hispanics: 37.4 per 100,000 standard population for males and 24.5 for females. Non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives were next at 10.8 (men) and 6.7 (women), followed by Hispanics (5.1/4.5), non-Hispanic Asians/Pacific Islanders (1.6/1.3), and non-Hispanic Blacks (1.2/1.0), they reported.

Death rates for melanoma, reported for 2014-2018, follow a similar pattern. White males (4.2 per 100,000) and females (1.8 per 100,000) had the highest mortality, then American Indians/Alaska Natives (1.0/0.5) and Hispanics (0.9/0.5), but rates were the same for Blacks and Asians/Pacific Islanders (0.4/0.3), the investigators said.

The accelerated decline in death rates in more recent years reflects “a substantial increase in survival for metastatic melanoma,” the participating organizations noted in a joint statement.

Increases in 2-year survival in distant-stage disease averaged 3.1% per year for those diagnosed during 2009-2014, which “slightly preceded the FDA approval of new therapies, likely because of the administration of these therapies through clinical trials and the FDA expanded access programs prior to the approval,” Dr. Islami and associates wrote.

The 2-year relative survival for those with nonmetastatic melanoma also improved over the study period, but the increases were much smaller: 0.4% per year for regional-stage disease and just 0.03% localized-stage cases diagnosed in 2001-2014, they reported.

The report was funded by the four participating groups. Six of the 12 investigators are employees of the American Cancer Society whose salaries are solely paid by the society; the other authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Fungemia, other fungal infections associated with s. Boulardii probiotics

Life-threatening fungal bloodstream infections associated with probiotic supplements have been reported in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases by a group of researchers in Finland. While individuals consume these mixtures of bacteria and yeast in the hopes of “balancing” their microbiome or preventing diarrhea from antibiotic use, some died or developed yeast infections requiring prolonged antifungal treatment.

In a retrospective registry study at five university hospitals in Finland, the researchers found 46 patients between 2009 and 2018 with Saccharomyces sp. of yeast in their blood associated with ingesting probiotics. At least 20 (43%) had been using S. cerevisiae var. boulardii as a probiotic, with the organism then causing a bloodstream infection. Overall, 37% of the fungemic patients died.

Juha Rannikko, MD, lead author and infectious disease faculty member at Tampere University Hospital, Finland, said in an interview that there were an additional 1,153 nonblood isolates of Saccharomyces. He expressed surprise at the large number of nonblood isolates, saying: “If extrapolated ... it is about 10 nonblood Saccharomyces boulardii–associated findings for each Saccharomyces boulardii–associated fungemia.”

Most of the yeast infections (59%) occurred in patients with underlying gastrointestinal disease. Prior studies suggested that patients receiving enteral nutrition might become ill from translocation of the yeast from the inflamed GI tract.

If there were positive cultures for yeast from sites other than blood, physicians changed the antibiotics in 38% of patients.

Conventional wisdom has been that patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics should also receive an S. cerevisiae var. boulardii probiotic to prevent Clostridioides difficile infections. Dr. Rannikko and coauthors questioned this, noting results of such studies of prophylaxis were equivocal. “There is not enough evidence that clinicians should use Saccharomyces (probiotics) alongside antibiotics,” Dr. Rannikko concluded.

Laila Woc-Colburn, MD, associate professor at the Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, told this news organization that although the study was well done and was published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, the findings do not represent an “emerging” infectious disease. “We have known this for a while – since the 1990s,” she said. Warnings about probiotics are part of the standard advice Dr. Woc-Colburn gives transplant, chemotherapy, or immunosuppressed patients. “Don’t do these probiotics, because this is what’s going to happen,” she tells them. And she told this news organization, “If I see this in the blood, the first question I’m going to ask my patients is ... what probiotic were you drinking?”

Dr. Woc-Colburn said the Finnish researchers “did their due diligence” when conducting the study. “They were clear on their limitations. And they came out to the same conclusion as the 2005 Muñoz paper: That if we have some GI disruption, we should not be taking probiotics.”

She acknowledged that the Emerging Infectious Diseases study adds a substantial number of cases to those previously reported in the literature and confirms previous findings and recommendations to avoid probiotics if immunosuppressed or acutely ill.

Dr. Rannikko and Dr. Woc-Coburn have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rannikko has received a lecture fee from Novo Nordisk and a virtual congress attendance fee from Roche.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Life-threatening fungal bloodstream infections associated with probiotic supplements have been reported in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases by a group of researchers in Finland. While individuals consume these mixtures of bacteria and yeast in the hopes of “balancing” their microbiome or preventing diarrhea from antibiotic use, some died or developed yeast infections requiring prolonged antifungal treatment.

In a retrospective registry study at five university hospitals in Finland, the researchers found 46 patients between 2009 and 2018 with Saccharomyces sp. of yeast in their blood associated with ingesting probiotics. At least 20 (43%) had been using S. cerevisiae var. boulardii as a probiotic, with the organism then causing a bloodstream infection. Overall, 37% of the fungemic patients died.

Juha Rannikko, MD, lead author and infectious disease faculty member at Tampere University Hospital, Finland, said in an interview that there were an additional 1,153 nonblood isolates of Saccharomyces. He expressed surprise at the large number of nonblood isolates, saying: “If extrapolated ... it is about 10 nonblood Saccharomyces boulardii–associated findings for each Saccharomyces boulardii–associated fungemia.”

Most of the yeast infections (59%) occurred in patients with underlying gastrointestinal disease. Prior studies suggested that patients receiving enteral nutrition might become ill from translocation of the yeast from the inflamed GI tract.

If there were positive cultures for yeast from sites other than blood, physicians changed the antibiotics in 38% of patients.

Conventional wisdom has been that patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics should also receive an S. cerevisiae var. boulardii probiotic to prevent Clostridioides difficile infections. Dr. Rannikko and coauthors questioned this, noting results of such studies of prophylaxis were equivocal. “There is not enough evidence that clinicians should use Saccharomyces (probiotics) alongside antibiotics,” Dr. Rannikko concluded.

Laila Woc-Colburn, MD, associate professor at the Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, told this news organization that although the study was well done and was published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, the findings do not represent an “emerging” infectious disease. “We have known this for a while – since the 1990s,” she said. Warnings about probiotics are part of the standard advice Dr. Woc-Colburn gives transplant, chemotherapy, or immunosuppressed patients. “Don’t do these probiotics, because this is what’s going to happen,” she tells them. And she told this news organization, “If I see this in the blood, the first question I’m going to ask my patients is ... what probiotic were you drinking?”

Dr. Woc-Colburn said the Finnish researchers “did their due diligence” when conducting the study. “They were clear on their limitations. And they came out to the same conclusion as the 2005 Muñoz paper: That if we have some GI disruption, we should not be taking probiotics.”

She acknowledged that the Emerging Infectious Diseases study adds a substantial number of cases to those previously reported in the literature and confirms previous findings and recommendations to avoid probiotics if immunosuppressed or acutely ill.

Dr. Rannikko and Dr. Woc-Coburn have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rannikko has received a lecture fee from Novo Nordisk and a virtual congress attendance fee from Roche.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Life-threatening fungal bloodstream infections associated with probiotic supplements have been reported in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases by a group of researchers in Finland. While individuals consume these mixtures of bacteria and yeast in the hopes of “balancing” their microbiome or preventing diarrhea from antibiotic use, some died or developed yeast infections requiring prolonged antifungal treatment.

In a retrospective registry study at five university hospitals in Finland, the researchers found 46 patients between 2009 and 2018 with Saccharomyces sp. of yeast in their blood associated with ingesting probiotics. At least 20 (43%) had been using S. cerevisiae var. boulardii as a probiotic, with the organism then causing a bloodstream infection. Overall, 37% of the fungemic patients died.

Juha Rannikko, MD, lead author and infectious disease faculty member at Tampere University Hospital, Finland, said in an interview that there were an additional 1,153 nonblood isolates of Saccharomyces. He expressed surprise at the large number of nonblood isolates, saying: “If extrapolated ... it is about 10 nonblood Saccharomyces boulardii–associated findings for each Saccharomyces boulardii–associated fungemia.”

Most of the yeast infections (59%) occurred in patients with underlying gastrointestinal disease. Prior studies suggested that patients receiving enteral nutrition might become ill from translocation of the yeast from the inflamed GI tract.

If there were positive cultures for yeast from sites other than blood, physicians changed the antibiotics in 38% of patients.

Conventional wisdom has been that patients receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics should also receive an S. cerevisiae var. boulardii probiotic to prevent Clostridioides difficile infections. Dr. Rannikko and coauthors questioned this, noting results of such studies of prophylaxis were equivocal. “There is not enough evidence that clinicians should use Saccharomyces (probiotics) alongside antibiotics,” Dr. Rannikko concluded.

Laila Woc-Colburn, MD, associate professor at the Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, told this news organization that although the study was well done and was published in Emerging Infectious Diseases, the findings do not represent an “emerging” infectious disease. “We have known this for a while – since the 1990s,” she said. Warnings about probiotics are part of the standard advice Dr. Woc-Colburn gives transplant, chemotherapy, or immunosuppressed patients. “Don’t do these probiotics, because this is what’s going to happen,” she tells them. And she told this news organization, “If I see this in the blood, the first question I’m going to ask my patients is ... what probiotic were you drinking?”

Dr. Woc-Colburn said the Finnish researchers “did their due diligence” when conducting the study. “They were clear on their limitations. And they came out to the same conclusion as the 2005 Muñoz paper: That if we have some GI disruption, we should not be taking probiotics.”

She acknowledged that the Emerging Infectious Diseases study adds a substantial number of cases to those previously reported in the literature and confirms previous findings and recommendations to avoid probiotics if immunosuppressed or acutely ill.

Dr. Rannikko and Dr. Woc-Coburn have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Rannikko has received a lecture fee from Novo Nordisk and a virtual congress attendance fee from Roche.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Artificial intelligence wish list

Dear big-tech AI company,

I do understand, the benefits of artificial intelligence today are already profound and protean. Thanks to AI, I can translate Italian to English in real time in the same voice as an Italian speaker. I can be driven home autonomously by our Tesla. AI helps keep me safe by predicting crimes, on time by predicting traffic, and healthy by designing plant proteins that taste just like beef. I can even use AI to build a sprinkler to keep people off my new lawn.

In medicine, the AI news is so good that a frisson of excitement spreads vertically and horizontally across all health care. AI can detect pulmonary nodules, identify melanomas, develop new drugs – speed vaccine discovery! – and detect malignant cells on a biopsy slide. It can help predict who is going to crash in the ICU and recognize when someone is about to fall out of bed in the surgical unit. Even just this sampling of benefits proves how significant and impactful AI is in improving quality of life for patients and populations.

However, much of what I do every day in medicine cannot be solved with a neat quantitative analysis. The vast majority of my patients do not have a melanoma to be diagnosed or diabetic retinopathy to be scanned. What they want and need is time spent with me, their doctor. Although the schedule says I have 15 minutes (insufficient to begin with), patients are running late and are double booked, and I’ve loads of notes to type, medications to review, and messages to answer. Most days, I have only a fraction of 15 minutes to spend face to face with each patient.

Can AI please help us? How about reviewing the reams of data from my patient’s chart and presenting it to me succinctly? Rather than my tediously clicking through pathology reports, just summarize what skin cancers my patient has had and when. Rather than learning that my patient already failed Protopic a year ago, let me know that before I sign the order and promise: “Now, this ointment will work.” Even better, suggest alternative treatments that I might not be thinking of and which might do just the trick. Oh, and given my EMR has all the data required to determine billing codes, can you just drop that in for me when I’m done? Lastly, if the patient’s insurance is going to reject this claim or that medication, can AI please complete the authorization/paperwork/signed notary document/letter from U.S. senator that will be needed for it to be accepted?

I know this is possible. If we can blast a 70-year-old businessman into space on a private jet, surely you can invent an AI that gives us more time to spend with patients. Proposals postmarked by Dec. 31, 2021, please.

I’m sincerely yours,

Jeff Benabio, MD, MBA

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Dear big-tech AI company,

I do understand, the benefits of artificial intelligence today are already profound and protean. Thanks to AI, I can translate Italian to English in real time in the same voice as an Italian speaker. I can be driven home autonomously by our Tesla. AI helps keep me safe by predicting crimes, on time by predicting traffic, and healthy by designing plant proteins that taste just like beef. I can even use AI to build a sprinkler to keep people off my new lawn.

In medicine, the AI news is so good that a frisson of excitement spreads vertically and horizontally across all health care. AI can detect pulmonary nodules, identify melanomas, develop new drugs – speed vaccine discovery! – and detect malignant cells on a biopsy slide. It can help predict who is going to crash in the ICU and recognize when someone is about to fall out of bed in the surgical unit. Even just this sampling of benefits proves how significant and impactful AI is in improving quality of life for patients and populations.

However, much of what I do every day in medicine cannot be solved with a neat quantitative analysis. The vast majority of my patients do not have a melanoma to be diagnosed or diabetic retinopathy to be scanned. What they want and need is time spent with me, their doctor. Although the schedule says I have 15 minutes (insufficient to begin with), patients are running late and are double booked, and I’ve loads of notes to type, medications to review, and messages to answer. Most days, I have only a fraction of 15 minutes to spend face to face with each patient.

Can AI please help us? How about reviewing the reams of data from my patient’s chart and presenting it to me succinctly? Rather than my tediously clicking through pathology reports, just summarize what skin cancers my patient has had and when. Rather than learning that my patient already failed Protopic a year ago, let me know that before I sign the order and promise: “Now, this ointment will work.” Even better, suggest alternative treatments that I might not be thinking of and which might do just the trick. Oh, and given my EMR has all the data required to determine billing codes, can you just drop that in for me when I’m done? Lastly, if the patient’s insurance is going to reject this claim or that medication, can AI please complete the authorization/paperwork/signed notary document/letter from U.S. senator that will be needed for it to be accepted?

I know this is possible. If we can blast a 70-year-old businessman into space on a private jet, surely you can invent an AI that gives us more time to spend with patients. Proposals postmarked by Dec. 31, 2021, please.

I’m sincerely yours,

Jeff Benabio, MD, MBA

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Dear big-tech AI company,

I do understand, the benefits of artificial intelligence today are already profound and protean. Thanks to AI, I can translate Italian to English in real time in the same voice as an Italian speaker. I can be driven home autonomously by our Tesla. AI helps keep me safe by predicting crimes, on time by predicting traffic, and healthy by designing plant proteins that taste just like beef. I can even use AI to build a sprinkler to keep people off my new lawn.

In medicine, the AI news is so good that a frisson of excitement spreads vertically and horizontally across all health care. AI can detect pulmonary nodules, identify melanomas, develop new drugs – speed vaccine discovery! – and detect malignant cells on a biopsy slide. It can help predict who is going to crash in the ICU and recognize when someone is about to fall out of bed in the surgical unit. Even just this sampling of benefits proves how significant and impactful AI is in improving quality of life for patients and populations.

However, much of what I do every day in medicine cannot be solved with a neat quantitative analysis. The vast majority of my patients do not have a melanoma to be diagnosed or diabetic retinopathy to be scanned. What they want and need is time spent with me, their doctor. Although the schedule says I have 15 minutes (insufficient to begin with), patients are running late and are double booked, and I’ve loads of notes to type, medications to review, and messages to answer. Most days, I have only a fraction of 15 minutes to spend face to face with each patient.

Can AI please help us? How about reviewing the reams of data from my patient’s chart and presenting it to me succinctly? Rather than my tediously clicking through pathology reports, just summarize what skin cancers my patient has had and when. Rather than learning that my patient already failed Protopic a year ago, let me know that before I sign the order and promise: “Now, this ointment will work.” Even better, suggest alternative treatments that I might not be thinking of and which might do just the trick. Oh, and given my EMR has all the data required to determine billing codes, can you just drop that in for me when I’m done? Lastly, if the patient’s insurance is going to reject this claim or that medication, can AI please complete the authorization/paperwork/signed notary document/letter from U.S. senator that will be needed for it to be accepted?

I know this is possible. If we can blast a 70-year-old businessman into space on a private jet, surely you can invent an AI that gives us more time to spend with patients. Proposals postmarked by Dec. 31, 2021, please.

I’m sincerely yours,

Jeff Benabio, MD, MBA

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Synthetic snake venom to the rescue? Potential uses in skin health and rejuvenation

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras,four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras,four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

1 This column discusses some of the emerging data in this novel area of medical and dermatologic research. For more detailed information, a review on the therapeutic potential of peptides in animal venom was published in 2003 (Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003 Oct;2[10]:790-802).

The potential of peptides found in snake venom

Snake venom is known to contain carbohydrates, nucleosides, amino acids, and lipids, as well as enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins and peptides, with proteins and peptides comprising the primary components.2

There are many different types of peptides in snake venom. The peptides and the small proteins found in snake venoms are known to confer a wide range of biologic activities, including antimicrobial, antihypertensive, analgesic, antitumor, and analgesic, in addition to several others. These peptides have been included in antiaging skin care products.3Pennington et al. have observed that venom-derived peptides appear to have potential as effective therapeutic agents in cosmetic formulations.4 In particular, Waglerin peptides appear to act with a Botox-like paralyzing effect and purportedly diminish skin wrinkles.5

Issues with efficacy of snake venom in skin care products

As with many skin care ingredients, what is seen in cell cultures or a laboratory setting may not translate to real life use. Shelf life, issues during manufacturing, interaction with other ingredients in the product, interactions with other products in the regimen, exposure to air and light, and difficulty of penetration can all affect efficacy. With snake venom in particular, stability and penetration make the efficacy in skin care products questionable.

The problem with many peptides in skin care products is that they are usually larger than 500 Dalton and, therefore, cannot penetrate into the skin. Bos et al. described the “500 Dalton rule” in 2000.6 Regardless of these issues, there are several publications looking at snake venom that will be discussed here.

Antimicrobial and wound healing activity

In 2011, Samy et al. found that phospholipase A2 purified from crotalid snake venom expressed antibacterial activity in vitro against various clinical human pathogens. The investigators synthesized peptides based on the sequence homology and ascertained that the synthetic peptides exhibited potent microbicidal properties against Gram-negative and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria with diminished toxicity against normal human cells. Subsequently, the investigators used a BALB/c mouse model to show that peptide-treated animals displayed accelerated healing of full-thickness skin wounds, with increased re-epithelialization, collagen production, and angiogenesis. They concluded that the protein/peptide complex developed from snake venoms was effective at fostering wound healing.7

In that same year, Samy et al. showed in vivo that the snake venom phospholipase A₂ (svPLA₂) proteins from Viperidae and Elapidae snakes activated innate immunity in the animals tested, providing protection against skin infection caused by S. aureus. In vitro experiments also revealed that svPLA₂ proteins dose dependently exerted bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects on S. aureus.8 In 2015, Al-Asmari et al. comparatively assessed the venoms of two cobras,four vipers, a standard antibiotic, and an antimycotic as antimicrobial agents. The methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was the most susceptible, followed by Gram-positive S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. While the antibiotic vancomycin was more effective against P. aeruginosa, the venoms more efficiently suppressed the resistant bacteria. The snake venoms had minimal effect on the fungus Candida albicans. The investigators concluded that the snake venoms exhibited antibacterial activity comparable to antibiotics and were more efficient in tackling resistant bacteria.9 In a review of animal venoms in 2017, Samy et al. reported that snake venom–derived synthetic peptide/snake cathelicidin exhibits robust antimicrobial and wound healing capacity, despite its instability and risk, and presents as a possible new treatment for S. aureus infections. They indicated that antimicrobial peptides derived from various animal venoms, including snakes, spiders, and scorpions, are in early experimental and preclinical development stages, and these cysteine-rich substances share hydrophobic alpha-helices or beta-sheets that yield lethal pores and membrane-impairing results on bacteria.10

New drugs and emerging indications

An ingredient that is said to mimic waglerin-1, a snake venom–derived peptide, is the main active ingredient in the Hanskin Syn-Ake Peptide Renewal Mask, a Korean product, which reportedly promotes facial muscle relaxation and wrinkle reduction, as the waglerin-1 provokes neuromuscular blockade via reversible antagonism of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.2,4,5

Waheed et al. reported in 2017 that recent innovations in molecular research have led to scientific harnessing of the various proteins and peptides found in snake venoms to render them salutary, rather than toxic. Most of the drug development focuses on coagulopathy, hemostasis, and anticancer functions, but research continues in other areas.11 According to An et al., several studies have also been performed on the use of snake venom to treat atopic dermatitis.12

Conclusion

Snake venom is a substance known primarily for its extreme toxicity, but it seems to offer promise for having beneficial effects in medicine. Due to its size and instability, it is doubtful that snake venom will have utility as a topical application in the dermatologic arsenal. In spite of the lack of convincing evidence, a search on Amazon.com brings up dozens of various skin care products containing snake venom. Much more research is necessary, of course, to see if there are methods to facilitate entry of snake venom into the dermis and if this is even desirable.

Snake venom is, in fact, my favorite example of a skin care ingredient that is a waste of money in skin care products. Do you have any favorite “charlatan skincare ingredients”? If so, feel free to contact me, and I will write a column. As dermatologists, we have a responsibility to debunk skin care marketing claims not supported by scientific evidence. I am here to help.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Nguyen JK et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Jul;19(7):1555-69.

2. Munawar A et al. Snake venom peptides: tools of biodiscovery. Toxins (Basel). 2018 Nov 14;10(11):474.

3. Almeida JR et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(30):3254-82.

4. Pennington MW et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018 Jun 1;26(10):2738-58.

5. Debono J et al. J Mol Evol. 2017 Jan;84(1):8-11.

6. Bos JD, Meinardi MM. Exp Dermatol. 2000 Jun;9(3):165-9.

7. Samy RP et al. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;716:245-65.

8. Samy RP et al. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(33):5104-13.

9. Al-Asmari AK et al. Open Microbiol J. 2015 Jul;9:18-25.

10. Perumal Samy R et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017 Jun 15;134:127-38.

11. Waheed H et al. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(17):1874-91.

12. An HJ et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2018 Dec;175(23):4310-24.

The febrile infant: New AAP guidance for the first 2 months of life

Sixteen years in the making, the American Academy of Pediatrics just released a new clinical practice guideline (CPG), “Evaluation and Management of Well-Appearing Febrile Infants 8-60 Days Old”. The recommendations were derived from interpretations of sequential studies in young, febrile, but well-appearing infants that covered invasive bacterial infection (IBI) incidence, diagnostic modalities, and treatment during the first 2 months of life, further refining approaches to evaluation and empirical treatment.

Pediatricians have long had solid information to help assess the risk for IBI among febrile infants aged 0-3 months, but there has been an ongoing desire to further refine the suggested evaluation of these very young infants. A study of febrile infants from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings network along with subsequent evidence has identified the first 3 weeks of life as the period of highest risk for IBI, with risk declining in a graded fashion aged between 22 and 56 days.

Critical caveats

First, some caveats. Infants 0-7 days are not addressed in the CPG, and all should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation according to newborn protocols. Second, the recommendations apply only to “well-appearing” infants. Any ill-appearing infant should be treated as high risk and receive full IBI evaluation and begun on empirical antimicrobials. Third, even though the CPG deals with infants as young as 8-21 days old, the recommendations are to treat all infants in this age group as high risk, even if well-appearing, and complete full IBI evaluation and empirical therapy while awaiting results. Fourth, these guidelines apply only to infants born at 37 weeks’ gestation or more. Finally, the new CPG action statements are meant to be recommendations rather than a standard of medical care, leaving some leeway for clinician interpretation of individual patient scenarios. Where appropriate, parents’ values and preferences should be incorporated as part of shared decision-making.

The CPG divides young, febrile infants into three cohorts based on age:

- 8-21 days old

- 22-28 days old

- 29-60 days old

Age 8-21 days

For well-appearing febrile infants 8-21 days old, the CPG recommends a complete IBI evaluation that includes urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for culture, approaching all infants in this cohort as high risk. Inflammatory markers may be obtained, but the evidence is not comprehensive enough to evaluate their role in decision-making for this age group. A two-step urine evaluation method (urine analysis followed by culture if the urine analysis looks concerning) is not recommended for infants aged 8-21 days. Urine samples for culture from these young infants should be obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration.

The CPG recommends drawing blood cultures and CSF by lumbar puncture from this cohort. These infants should be admitted to the hospital, treated empirically with antimicrobials, and actively monitored. However, if the cultures are negative at 24-36 hours, the clinician should discontinue antimicrobials and discharge the infant if there is no other reason for continued hospitalization.

Age 22-28 days

Well-appearing, febrile infants 22-28 days old are in an intermediate-risk zone. The recommendation for infants in this cohort is to obtain a urine specimen by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration for both urine analysis and culture. Clinicians may consider obtaining urine samples for analysis noninvasively (e.g., urine bag) in this cohort, but this is not the preferred method.

Blood culture should be obtained from all infants in this group. Inflammatory markers can help clinicians identify infants at greater risk for IBI, including meningitis. Previous data suggested that inflammatory markers such as serum white blood cell counts greater than 11,000/mcL, a serum absolute neutrophil count of greater than 4,000/mcL, and elevated C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels could help providers identify febrile infants with true IBI. A 2008 study demonstrated that procalcitonin had the best receiver operating characteristic curve in regard to predicting IBI in young febrile infants. Other research backed up that finding and identified cutoff values for procalcitonin levels greater than 1.0 ng/mL. The CPG recommends considering a procalcitonin value of 0.5 ng/mL or higher as positive, indicating that the infant is at greater risk for IBI and potentially should undergo an expanded IBI workup. Therefore, in infants aged 22-28 days, inflammatory markers can play a role in deciding whether to perform a lumbar puncture.

Many more nuanced recommendations for whether to and how to empirically treat with antimicrobials in this cohort can be found in the CPG, including whether to manage in the hospital or at home. Treatment recommendations vary greatly for this cohort on the basis of the tests obtained and whether tests were positive or negative at the initial evaluation.

Age 29-60 days

The CPG will be most helpful when clinicians are faced with well-appearing, febrile infants in the 29- to 60-day age group. As with the other groups, a urine evaluation is recommended; however, the CPG suggests that the two-step approach – obtaining a urine analysis by a noninvasive method and only obtaining culture if the urine analysis is positive – is reasonable. This means that a bag or free-flowing urine specimen would be appropriate for urinalysis, followed by catheterization/suprapubic aspiration if a culture is necessary. This would save approximately 90% of infants from invasive urine collection. Regardless, only catheter or suprapubic specimens are appropriate for urine culture.

The CPG also recommends that clinicians obtain blood culture on all of these infants. Inflammatory markers should be assessed in this cohort because avoiding lumbar puncture for CSF culture would be appropriate in this cohort if the inflammatory markers are negative. If CSF is obtained in this age cohort, enterovirus testing should be added to the testing regimen. Again, for any infant considered at higher risk for IBI on the basis of screening tests, the CPG recommends a 24- to 36-hour rule-out period with empirical antimicrobial treatment and active monitoring in the hospital.

Summary

The recommended approach for febrile infants 8-21 days old is relatively aggressive, with urine, blood, and CSF evaluation for IBI. Clinicians gain some leeway for infants age 22-28 days, but the guidelines recommend a more flexible approach to evaluating well-appearing, febrile infants age 29-60 days, when a two-step urine evaluation and inflammatory marker assessment can help clinicians and parents have a better discussion about the risk-benefit trade-offs of more aggressive testing and empirical treatment.

The author would like to thank Ken Roberts, MD, for his review and helpful comments on this summary of the CPG highlights. Summary points of the CPG were presented by the writing group at the 2021 Pediatric Academic Societies meeting.