User login

Empagliflozin cut PA pressures in heart failure patients

Elevated pulmonary artery diastolic pressure is “perhaps the best predictor of bad outcomes in patients with heart failure, including hospitalization and death,” and new evidence clearly showed that the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin cuts this metric in patients by a clinically significant amount, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The evidence he collected from a total of 65 heart failure patients with either reduced or preserved ejection fraction is the first documentation from a randomized, controlled study to show a direct effect by a SGLT2 inhibitor on pulmonary artery (PA) pressures.

Other key findings were that the drop in PA diastolic pressure with empagliflozin treatment compared with placebo became discernible early (within the first 4 weeks on treatment), that the pressure-lowering effect steadily grew over time, and that it showed no link to the intensity of loop diuretic treatment, which held steady during 12 weeks on treatment and 13 weeks of overall monitoring.

The study’s primary endpoint was the change from baseline in PA diastolic pressure after 12 weeks on treatment. The 31 patients who completed the full 12-week course had an average drop in their PA diastolic pressure of about 1.5 mm Hg, compared with 28 patients who completed 12 weeks on placebo. Average PA diastolic pressure at baseline was about 21 mm Hg in both treatment arms, and on treatment this fell by more than 0.5 mm Hg among those who received empagliflozin and rose by close to 1 mm Hg among control patients.

“There appears to be a direct effect of empagliflozin on pulmonary artery pressure that’s not been previously demonstrated” by an SGLT2 inhibitor, Dr. Kosiborod said. “I think this is one mechanism of action” for this drug class. “If you control pulmonary artery filling pressures you can prevent hospitalizations and deaths.”

Small reductions matter

“Small pressure differences are particularly important for pulmonary hypertension,” commented Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and the report’s designated discussant.

“In the Vanderbilt heart failure database, patients with a pulmonary artery mean pressure of 20-24 mm Hg had 30% higher mortality than patients with lower pressures,” Dr. Stevenson noted. “This has led to a new definition of pulmonary hypertension, a mean pulmonary artery pressure above at or above 20 mm Hg.”

In Dr. Kosiborod’s study, patients began with an average PA mean pressure of about 30 mm Hg, and empagliflozin treatment led to a reduction in this metric with about the same magnitude as its effect on PA diastolic pressure. Empagliflozin also produced a similar reduction in average PA systolic pressure.

A study built on ambulatory PA monitoring

The results “also provide more proof for the concept of ambulatory hemodynamic monitoring” in patients with heart failure to monitor their status, she added. The study enrolled only patients who had already received a CardioMEMS implant as part of their routine care. This device allows for frequent, noninvasive monitoring of PA pressures. Researchers collected PA pressure data from patients twice daily for the entire 13-week study.

The EMBRACE HF (Empagliflozin Impact on Hemodynamics in Patients With Heart Failure) study enrolled patients with established heart failure, a CardioMEMS implant, and New York Heart Association class II-IV symptoms at any of eight U.S. centers. Patients averaged about 65 years old, and slightly more than half had class III disease, which denotes marked limitation of physical activity.

Despite the brief treatment period, patients who received empagliflozin showed other evidence of benefit including a trend toward improved quality of life scores, reduced levels of two different forms of brain natriuretic peptide, and significant weight loss, compared with controls, that averaged 2.4 kg.

The mechanism by which empagliflozin and other drugs in its class might lower PA filling pressures is unclear, but Dr. Kosiborod stressed that the consistent level of loop diuretic use during the study seems to rule out a diuretic effect from the SGLT2 inhibitor as having a role. A pulmonary vasculature effect is “much more likely,” perhaps mediated through modified endothelial function and vasodilation, he suggested.

EMBRACE HF was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets empagliflozin (Jardiance) along with Eli Lilly. Dr. Kosiborod has received research support and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has received honoraria from several other companies. Dr. Stevenson had no disclosures.

Elevated pulmonary artery diastolic pressure is “perhaps the best predictor of bad outcomes in patients with heart failure, including hospitalization and death,” and new evidence clearly showed that the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin cuts this metric in patients by a clinically significant amount, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The evidence he collected from a total of 65 heart failure patients with either reduced or preserved ejection fraction is the first documentation from a randomized, controlled study to show a direct effect by a SGLT2 inhibitor on pulmonary artery (PA) pressures.

Other key findings were that the drop in PA diastolic pressure with empagliflozin treatment compared with placebo became discernible early (within the first 4 weeks on treatment), that the pressure-lowering effect steadily grew over time, and that it showed no link to the intensity of loop diuretic treatment, which held steady during 12 weeks on treatment and 13 weeks of overall monitoring.

The study’s primary endpoint was the change from baseline in PA diastolic pressure after 12 weeks on treatment. The 31 patients who completed the full 12-week course had an average drop in their PA diastolic pressure of about 1.5 mm Hg, compared with 28 patients who completed 12 weeks on placebo. Average PA diastolic pressure at baseline was about 21 mm Hg in both treatment arms, and on treatment this fell by more than 0.5 mm Hg among those who received empagliflozin and rose by close to 1 mm Hg among control patients.

“There appears to be a direct effect of empagliflozin on pulmonary artery pressure that’s not been previously demonstrated” by an SGLT2 inhibitor, Dr. Kosiborod said. “I think this is one mechanism of action” for this drug class. “If you control pulmonary artery filling pressures you can prevent hospitalizations and deaths.”

Small reductions matter

“Small pressure differences are particularly important for pulmonary hypertension,” commented Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and the report’s designated discussant.

“In the Vanderbilt heart failure database, patients with a pulmonary artery mean pressure of 20-24 mm Hg had 30% higher mortality than patients with lower pressures,” Dr. Stevenson noted. “This has led to a new definition of pulmonary hypertension, a mean pulmonary artery pressure above at or above 20 mm Hg.”

In Dr. Kosiborod’s study, patients began with an average PA mean pressure of about 30 mm Hg, and empagliflozin treatment led to a reduction in this metric with about the same magnitude as its effect on PA diastolic pressure. Empagliflozin also produced a similar reduction in average PA systolic pressure.

A study built on ambulatory PA monitoring

The results “also provide more proof for the concept of ambulatory hemodynamic monitoring” in patients with heart failure to monitor their status, she added. The study enrolled only patients who had already received a CardioMEMS implant as part of their routine care. This device allows for frequent, noninvasive monitoring of PA pressures. Researchers collected PA pressure data from patients twice daily for the entire 13-week study.

The EMBRACE HF (Empagliflozin Impact on Hemodynamics in Patients With Heart Failure) study enrolled patients with established heart failure, a CardioMEMS implant, and New York Heart Association class II-IV symptoms at any of eight U.S. centers. Patients averaged about 65 years old, and slightly more than half had class III disease, which denotes marked limitation of physical activity.

Despite the brief treatment period, patients who received empagliflozin showed other evidence of benefit including a trend toward improved quality of life scores, reduced levels of two different forms of brain natriuretic peptide, and significant weight loss, compared with controls, that averaged 2.4 kg.

The mechanism by which empagliflozin and other drugs in its class might lower PA filling pressures is unclear, but Dr. Kosiborod stressed that the consistent level of loop diuretic use during the study seems to rule out a diuretic effect from the SGLT2 inhibitor as having a role. A pulmonary vasculature effect is “much more likely,” perhaps mediated through modified endothelial function and vasodilation, he suggested.

EMBRACE HF was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets empagliflozin (Jardiance) along with Eli Lilly. Dr. Kosiborod has received research support and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has received honoraria from several other companies. Dr. Stevenson had no disclosures.

Elevated pulmonary artery diastolic pressure is “perhaps the best predictor of bad outcomes in patients with heart failure, including hospitalization and death,” and new evidence clearly showed that the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin cuts this metric in patients by a clinically significant amount, Mikhail Kosiborod, MD, said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The evidence he collected from a total of 65 heart failure patients with either reduced or preserved ejection fraction is the first documentation from a randomized, controlled study to show a direct effect by a SGLT2 inhibitor on pulmonary artery (PA) pressures.

Other key findings were that the drop in PA diastolic pressure with empagliflozin treatment compared with placebo became discernible early (within the first 4 weeks on treatment), that the pressure-lowering effect steadily grew over time, and that it showed no link to the intensity of loop diuretic treatment, which held steady during 12 weeks on treatment and 13 weeks of overall monitoring.

The study’s primary endpoint was the change from baseline in PA diastolic pressure after 12 weeks on treatment. The 31 patients who completed the full 12-week course had an average drop in their PA diastolic pressure of about 1.5 mm Hg, compared with 28 patients who completed 12 weeks on placebo. Average PA diastolic pressure at baseline was about 21 mm Hg in both treatment arms, and on treatment this fell by more than 0.5 mm Hg among those who received empagliflozin and rose by close to 1 mm Hg among control patients.

“There appears to be a direct effect of empagliflozin on pulmonary artery pressure that’s not been previously demonstrated” by an SGLT2 inhibitor, Dr. Kosiborod said. “I think this is one mechanism of action” for this drug class. “If you control pulmonary artery filling pressures you can prevent hospitalizations and deaths.”

Small reductions matter

“Small pressure differences are particularly important for pulmonary hypertension,” commented Lynne W. Stevenson, MD, professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and the report’s designated discussant.

“In the Vanderbilt heart failure database, patients with a pulmonary artery mean pressure of 20-24 mm Hg had 30% higher mortality than patients with lower pressures,” Dr. Stevenson noted. “This has led to a new definition of pulmonary hypertension, a mean pulmonary artery pressure above at or above 20 mm Hg.”

In Dr. Kosiborod’s study, patients began with an average PA mean pressure of about 30 mm Hg, and empagliflozin treatment led to a reduction in this metric with about the same magnitude as its effect on PA diastolic pressure. Empagliflozin also produced a similar reduction in average PA systolic pressure.

A study built on ambulatory PA monitoring

The results “also provide more proof for the concept of ambulatory hemodynamic monitoring” in patients with heart failure to monitor their status, she added. The study enrolled only patients who had already received a CardioMEMS implant as part of their routine care. This device allows for frequent, noninvasive monitoring of PA pressures. Researchers collected PA pressure data from patients twice daily for the entire 13-week study.

The EMBRACE HF (Empagliflozin Impact on Hemodynamics in Patients With Heart Failure) study enrolled patients with established heart failure, a CardioMEMS implant, and New York Heart Association class II-IV symptoms at any of eight U.S. centers. Patients averaged about 65 years old, and slightly more than half had class III disease, which denotes marked limitation of physical activity.

Despite the brief treatment period, patients who received empagliflozin showed other evidence of benefit including a trend toward improved quality of life scores, reduced levels of two different forms of brain natriuretic peptide, and significant weight loss, compared with controls, that averaged 2.4 kg.

The mechanism by which empagliflozin and other drugs in its class might lower PA filling pressures is unclear, but Dr. Kosiborod stressed that the consistent level of loop diuretic use during the study seems to rule out a diuretic effect from the SGLT2 inhibitor as having a role. A pulmonary vasculature effect is “much more likely,” perhaps mediated through modified endothelial function and vasodilation, he suggested.

EMBRACE HF was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that markets empagliflozin (Jardiance) along with Eli Lilly. Dr. Kosiborod has received research support and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, and he has received honoraria from several other companies. Dr. Stevenson had no disclosures.

FROM HFSA 2020

Prescribe Halloween safety by region, current conditions

Halloween is fast approaching and retail stores are fully stocked with costumes and candy. Physician dialog is beginning to shift from school access toward how to counsel patients and families on COVID-19 safety around Halloween. advised pediatrician Shelly Vaziri Flais, MD.

Halloween “is going to look very different this year, especially in urban and rural settings, according to Dr. Flais, who is a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. The notion that trick-or-treating automatically involves physically distancing is a misconception. Urban celebrations frequently see many people gathering on the streets, and that will be even more likely in a pandemic year when people have been separated for long periods of time.

For pediatricians advising families on COVID-19 safety measures to follow while celebrating Halloween, it’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all approach, said Dr. Flais, who practices pediatrics at Pediatric Health Associates in Naperville, Ill.

The goal for physicians across the board should be “to ensure that we aren’t so cautious that we drive folks to do things that are higher risk,” she said in an interview. “We are now 6-7 months into the pandemic and the public is growing weary of laying low, so it is important for physicians to not recommend safety measures that are too restrictive.”

The balance pediatricians will need to strike in advising their patients is tricky at best. So in dispensing advice, it is important to make sure that it has a benefit to the overall population, cautioned Dr. Flais. Activities such as hosting independently organized, heavily packed indoor gatherings where people are eating, drinking, and not wearing masks is not going to be beneficial for the masses.

“We’re all lucky that we have technology. We’ve gotten used to doing virtual hugs and activities on Zoom,” she said, adding that she has already seen some really creative ideas on social media for enjoying a COVID-conscious Halloween, including a festive candy chute created by an Ohio family that is perfect for distributing candy while minimizing physical contact.

In an AAP press release, Dr. Flais noted that “this is a good time to teach children the importance of protecting not just ourselves but each other.” How we choose to manage our safety and the safety of our children “can have a ripple effect on our family members.” It is possible to make safe, responsible choices when celebrating and still create magical memories for our children.

Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview, “ I certainly support the AAP recommendations. Because of the way COVID-19 virus is spread, I would emphasize with my patients that the No. 1 thing to do is to enforce facial mask wearing while out trick-or-treating.

“I would also err on the side of safety if my child was showing any signs of illness and find an alternative method of celebrating Halloween that would not involve close contact with other individuals,” said Dr. Rushton, who is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board.

AAP-recommended Do’s and Don’ts for celebrating Halloween

DO:

- Avoid large gatherings.

- Maintain 6 feet distance.

- Wear cloth masks and wash hands often.

- Use hand sanitizer before and after visiting pumpkin patches and apple orchards.

DON’T:

- Wear painted cloth masks since paints can contain toxins that should not be breathed.

- Use a costume mask unless it has layers of breathable fabric snugly covering mouth and nose.

- Wear cloth mask under costume mask.

- Attend indoor parties or haunted houses.

CDC safety considerations (supplemental to state and local safety laws)

- Assess current cases and overall spread in your community before making any plans.

- Choose outdoor venues or indoor facilities that are well ventilated.

- Consider the length of the event, how many are attending, where they are coming from, and how they behave before and during the event.

- If you are awaiting test results, have COVID-19 symptoms, or have been exposed to COVID-19, stay home.

- If you are at higher risk, avoid large gatherings and limit exposure to anyone you do not live with.

- Make available to others masks, 60% or greater alcohol-based hand sanitizer, and tissues.

- Avoid touching your nose, eyes, and mouth.

- For a complete set of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID safety recommendations go here.

Suggested safe, fun activities

- Use Zoom and other chat programs to share costumes, play games, and watch festive movies.

- Participate in socially distanced outdoor community events at local parks, zoos, etc.

- Attend haunted forests and corn mazes. Maintain more than 6 feet of distance around screaming patrons.

- Decorate pumpkins.

- Cook a Halloween-themed meal.

- If trick-or-treating has been canceled, try a scavenger hunt in the house or yard.

- When handing out treats, wear gloves and mask. Consider prepackaging treat bags. Line up visitors 6 feet apart and discourage gatherings around entranceways.

- Wipe down all goodies received and consider quarantining them for a few days.

- Always wash hands before and after trick-or-treating and when handling treats.

Halloween is fast approaching and retail stores are fully stocked with costumes and candy. Physician dialog is beginning to shift from school access toward how to counsel patients and families on COVID-19 safety around Halloween. advised pediatrician Shelly Vaziri Flais, MD.

Halloween “is going to look very different this year, especially in urban and rural settings, according to Dr. Flais, who is a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. The notion that trick-or-treating automatically involves physically distancing is a misconception. Urban celebrations frequently see many people gathering on the streets, and that will be even more likely in a pandemic year when people have been separated for long periods of time.

For pediatricians advising families on COVID-19 safety measures to follow while celebrating Halloween, it’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all approach, said Dr. Flais, who practices pediatrics at Pediatric Health Associates in Naperville, Ill.

The goal for physicians across the board should be “to ensure that we aren’t so cautious that we drive folks to do things that are higher risk,” she said in an interview. “We are now 6-7 months into the pandemic and the public is growing weary of laying low, so it is important for physicians to not recommend safety measures that are too restrictive.”

The balance pediatricians will need to strike in advising their patients is tricky at best. So in dispensing advice, it is important to make sure that it has a benefit to the overall population, cautioned Dr. Flais. Activities such as hosting independently organized, heavily packed indoor gatherings where people are eating, drinking, and not wearing masks is not going to be beneficial for the masses.

“We’re all lucky that we have technology. We’ve gotten used to doing virtual hugs and activities on Zoom,” she said, adding that she has already seen some really creative ideas on social media for enjoying a COVID-conscious Halloween, including a festive candy chute created by an Ohio family that is perfect for distributing candy while minimizing physical contact.

In an AAP press release, Dr. Flais noted that “this is a good time to teach children the importance of protecting not just ourselves but each other.” How we choose to manage our safety and the safety of our children “can have a ripple effect on our family members.” It is possible to make safe, responsible choices when celebrating and still create magical memories for our children.

Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview, “ I certainly support the AAP recommendations. Because of the way COVID-19 virus is spread, I would emphasize with my patients that the No. 1 thing to do is to enforce facial mask wearing while out trick-or-treating.

“I would also err on the side of safety if my child was showing any signs of illness and find an alternative method of celebrating Halloween that would not involve close contact with other individuals,” said Dr. Rushton, who is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board.

AAP-recommended Do’s and Don’ts for celebrating Halloween

DO:

- Avoid large gatherings.

- Maintain 6 feet distance.

- Wear cloth masks and wash hands often.

- Use hand sanitizer before and after visiting pumpkin patches and apple orchards.

DON’T:

- Wear painted cloth masks since paints can contain toxins that should not be breathed.

- Use a costume mask unless it has layers of breathable fabric snugly covering mouth and nose.

- Wear cloth mask under costume mask.

- Attend indoor parties or haunted houses.

CDC safety considerations (supplemental to state and local safety laws)

- Assess current cases and overall spread in your community before making any plans.

- Choose outdoor venues or indoor facilities that are well ventilated.

- Consider the length of the event, how many are attending, where they are coming from, and how they behave before and during the event.

- If you are awaiting test results, have COVID-19 symptoms, or have been exposed to COVID-19, stay home.

- If you are at higher risk, avoid large gatherings and limit exposure to anyone you do not live with.

- Make available to others masks, 60% or greater alcohol-based hand sanitizer, and tissues.

- Avoid touching your nose, eyes, and mouth.

- For a complete set of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID safety recommendations go here.

Suggested safe, fun activities

- Use Zoom and other chat programs to share costumes, play games, and watch festive movies.

- Participate in socially distanced outdoor community events at local parks, zoos, etc.

- Attend haunted forests and corn mazes. Maintain more than 6 feet of distance around screaming patrons.

- Decorate pumpkins.

- Cook a Halloween-themed meal.

- If trick-or-treating has been canceled, try a scavenger hunt in the house or yard.

- When handing out treats, wear gloves and mask. Consider prepackaging treat bags. Line up visitors 6 feet apart and discourage gatherings around entranceways.

- Wipe down all goodies received and consider quarantining them for a few days.

- Always wash hands before and after trick-or-treating and when handling treats.

Halloween is fast approaching and retail stores are fully stocked with costumes and candy. Physician dialog is beginning to shift from school access toward how to counsel patients and families on COVID-19 safety around Halloween. advised pediatrician Shelly Vaziri Flais, MD.

Halloween “is going to look very different this year, especially in urban and rural settings, according to Dr. Flais, who is a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago. The notion that trick-or-treating automatically involves physically distancing is a misconception. Urban celebrations frequently see many people gathering on the streets, and that will be even more likely in a pandemic year when people have been separated for long periods of time.

For pediatricians advising families on COVID-19 safety measures to follow while celebrating Halloween, it’s not going to be a one-size-fits-all approach, said Dr. Flais, who practices pediatrics at Pediatric Health Associates in Naperville, Ill.

The goal for physicians across the board should be “to ensure that we aren’t so cautious that we drive folks to do things that are higher risk,” she said in an interview. “We are now 6-7 months into the pandemic and the public is growing weary of laying low, so it is important for physicians to not recommend safety measures that are too restrictive.”

The balance pediatricians will need to strike in advising their patients is tricky at best. So in dispensing advice, it is important to make sure that it has a benefit to the overall population, cautioned Dr. Flais. Activities such as hosting independently organized, heavily packed indoor gatherings where people are eating, drinking, and not wearing masks is not going to be beneficial for the masses.

“We’re all lucky that we have technology. We’ve gotten used to doing virtual hugs and activities on Zoom,” she said, adding that she has already seen some really creative ideas on social media for enjoying a COVID-conscious Halloween, including a festive candy chute created by an Ohio family that is perfect for distributing candy while minimizing physical contact.

In an AAP press release, Dr. Flais noted that “this is a good time to teach children the importance of protecting not just ourselves but each other.” How we choose to manage our safety and the safety of our children “can have a ripple effect on our family members.” It is possible to make safe, responsible choices when celebrating and still create magical memories for our children.

Francis E. Rushton Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview, “ I certainly support the AAP recommendations. Because of the way COVID-19 virus is spread, I would emphasize with my patients that the No. 1 thing to do is to enforce facial mask wearing while out trick-or-treating.

“I would also err on the side of safety if my child was showing any signs of illness and find an alternative method of celebrating Halloween that would not involve close contact with other individuals,” said Dr. Rushton, who is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board.

AAP-recommended Do’s and Don’ts for celebrating Halloween

DO:

- Avoid large gatherings.

- Maintain 6 feet distance.

- Wear cloth masks and wash hands often.

- Use hand sanitizer before and after visiting pumpkin patches and apple orchards.

DON’T:

- Wear painted cloth masks since paints can contain toxins that should not be breathed.

- Use a costume mask unless it has layers of breathable fabric snugly covering mouth and nose.

- Wear cloth mask under costume mask.

- Attend indoor parties or haunted houses.

CDC safety considerations (supplemental to state and local safety laws)

- Assess current cases and overall spread in your community before making any plans.

- Choose outdoor venues or indoor facilities that are well ventilated.

- Consider the length of the event, how many are attending, where they are coming from, and how they behave before and during the event.

- If you are awaiting test results, have COVID-19 symptoms, or have been exposed to COVID-19, stay home.

- If you are at higher risk, avoid large gatherings and limit exposure to anyone you do not live with.

- Make available to others masks, 60% or greater alcohol-based hand sanitizer, and tissues.

- Avoid touching your nose, eyes, and mouth.

- For a complete set of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID safety recommendations go here.

Suggested safe, fun activities

- Use Zoom and other chat programs to share costumes, play games, and watch festive movies.

- Participate in socially distanced outdoor community events at local parks, zoos, etc.

- Attend haunted forests and corn mazes. Maintain more than 6 feet of distance around screaming patrons.

- Decorate pumpkins.

- Cook a Halloween-themed meal.

- If trick-or-treating has been canceled, try a scavenger hunt in the house or yard.

- When handing out treats, wear gloves and mask. Consider prepackaging treat bags. Line up visitors 6 feet apart and discourage gatherings around entranceways.

- Wipe down all goodies received and consider quarantining them for a few days.

- Always wash hands before and after trick-or-treating and when handling treats.

Paronychia and Target Lesions After Hematopoietic Cell Transplant

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

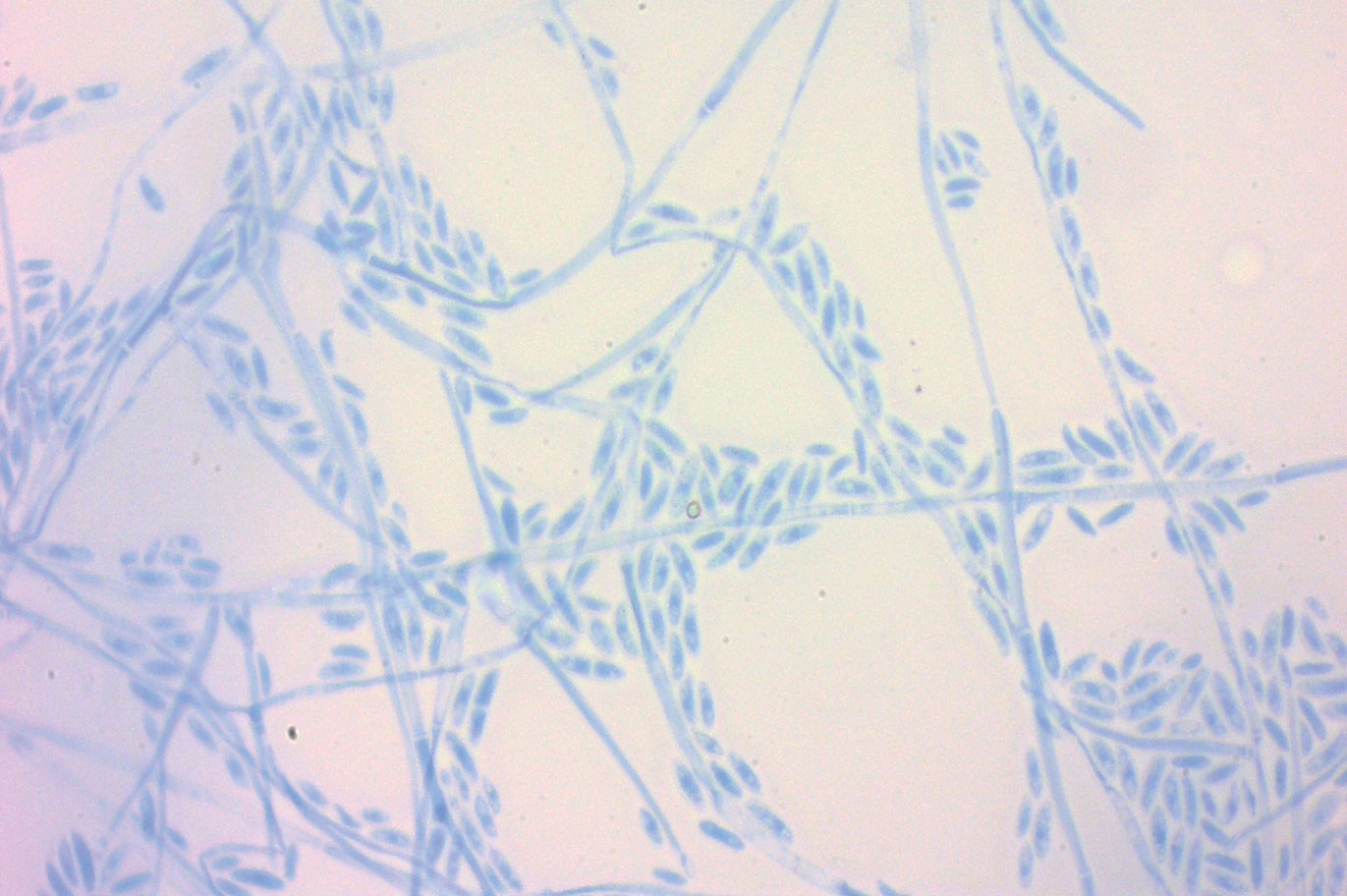

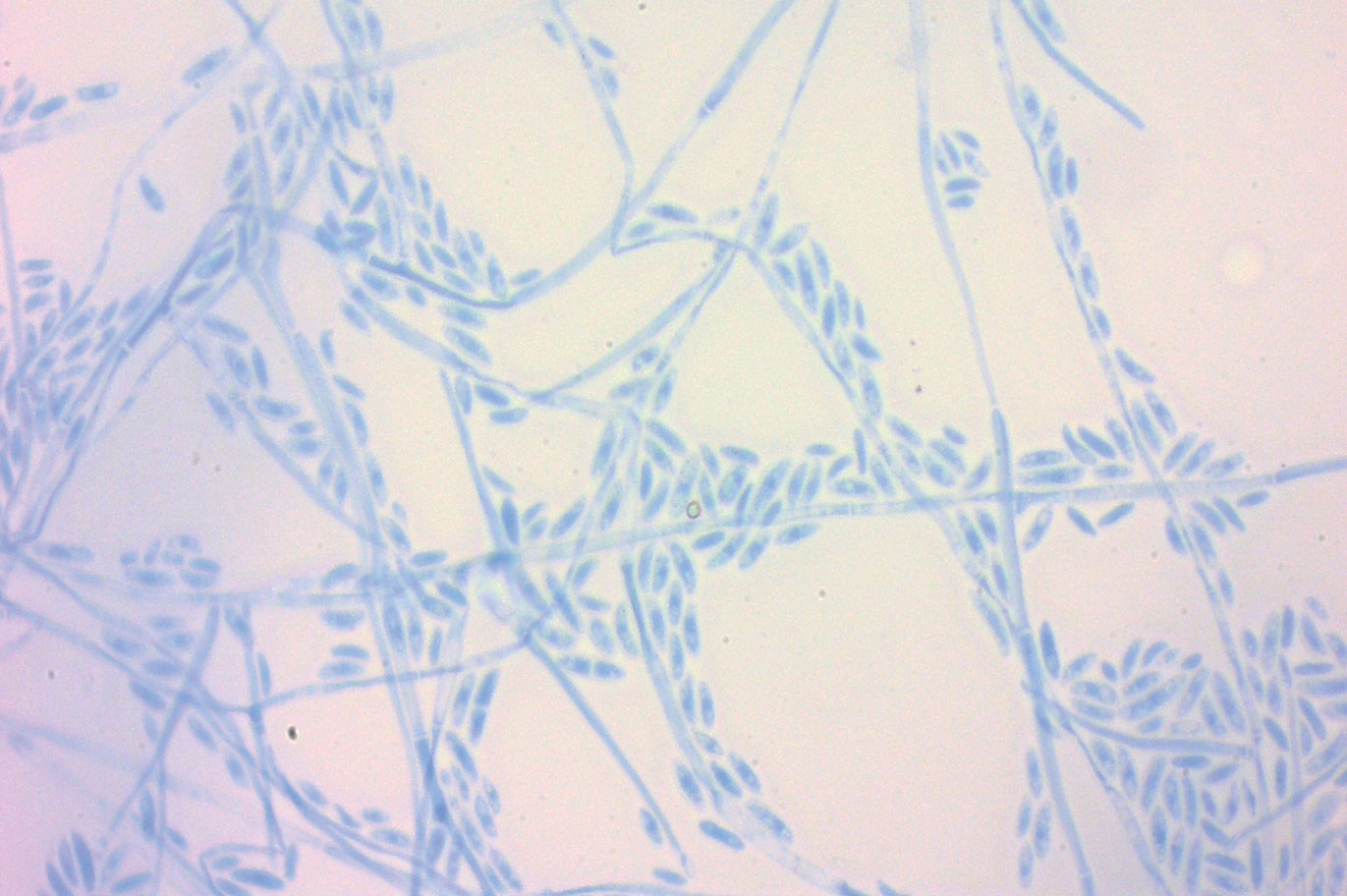

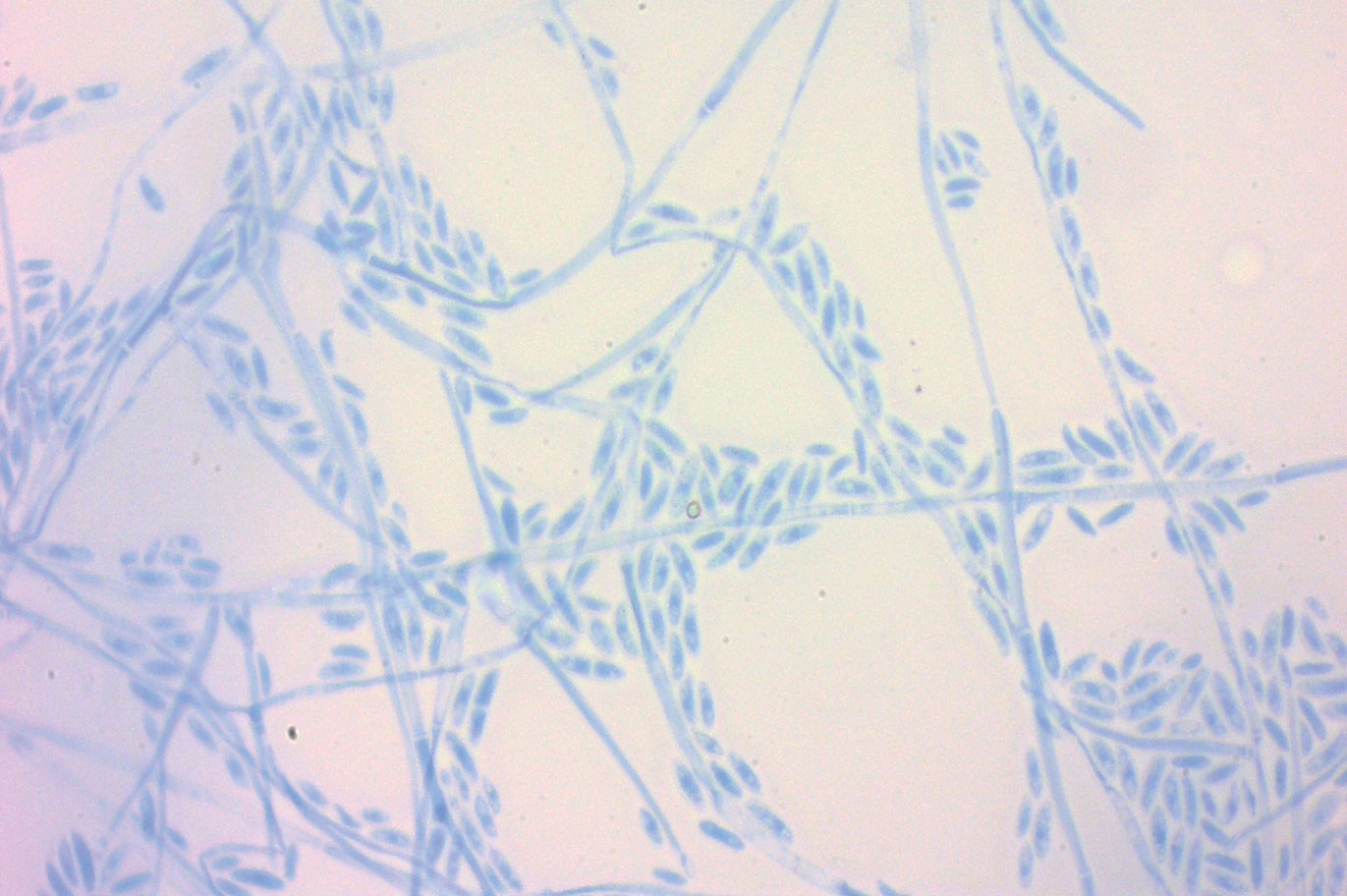

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

A 19-year-old man with acute lymphoblastic leukemia was admitted for an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. On the 11th day of hospitalization, he experienced a right toe trauma in his hospital room and subsequently developed edema, erythema, and pain on the right hallux (top). The next day, a general surgeon performed a minor incision and drainage of the affected area. After 2 days, the patient developed a fever and a disseminated dermatosis located on the arms and legs characterized by target lesions with a necrotic center and erythematous papules and macules (bottom). On day 3, he developed severe neutropenia (0.042×109 cells/L [reference range, 2.0–6.9×109 cells/L]). Broad-spectrum antibiotics were initiated without clinical improvement. The patient developed dyspnea on day 5. Skin, nail, and blood cultures were obtained. High-resolution computed tomography of the chest displayed multiple small pulmonary nodules, ground-glass opacities, and the tree-in-bud sign.

Mental health risks rise with age and stage for gender-incongruent youth

Gender-incongruent youth who present for gender-affirming medical care later in adolescence have higher rates of mental health problems than their younger counterparts, based on data from a review of 300 individuals.

“Puberty is a vulnerable time for youth with gender dysphoria because distress may intensify with the development of secondary sex characteristics corresponding to the assigned rather than the experienced gender,” wrote Julia C. Sorbara, MD, of the University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children, also in Toronto, and colleagues.

Although gender-affirming medical care (GAMC) in the form of hormone blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones early in puberty can decrease in emotional and behavioral problems, many teens present later in puberty, and the relationship between pubertal stage at presentation for treatment and mental health has not been examined, they wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from youth with gender incongruence who were seen at a single center; 116 were younger than 15 years at presentation for GAMC and were defined as younger-presenting youth (YPY), and 184 patients aged 15 years and older were defined as older-presenting youth (OPY).

Overall, 78% of the youth reported at least one mental health problem at their initial visit. Significantly more OPY than YPY reported diagnosed depression (46% vs. 30%), self-harm (40% vs. 28%), suicidal thoughts (52% vs. 40%), suicide attempts (17% vs. 9%), and use of psychoactive medications (36% vs. 23%), all with P < .05.

In a multivariate analysis, patients in Tanner stages 4 and 5 were five times more likely to experience depressive disorders (odds ratio, 5.49) and four times as likely to experience depressive disorders (OR, 4.18) as those in earlier Tanner stages. Older age remained significantly associated with use of psychoactive medications (OR, 1.31), but not with anxiety or depression, the researchers wrote.

The YPY group were significantly younger at the age of recognizing gender incongruence, compared with the OPY group, with median ages at recognition of 5.8 years and 9 years, respectively, and younger patients came out about their gender identity at an average of 12 years, compared with 15 years for older patients.

The quantitative data are among the first to relate pubertal stage to mental health in gender-incongruent youth, “supporting clinical observations that pubertal development, menses, and erections are distressing to these youth and consistent with the beneficial role of pubertal suppression, even when used as monotherapy without gender-affirming hormones,” Dr. Sorbara and associates wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and the collection of mental health data at only one time point and by the use of self-reports. However, the results suggest that “[gender-incongruent] youth who present to GAMC later in life are a particularly high-risk subset of a vulnerable population,” they noted. “Further study is required to better describe the mental health trajectories of transgender youth and determine if mental health status or age at initiation of GAMC is correlated with psychological well-being in adulthood.”

Don’t rush to puberty suppression in younger teens

To reduce the stress of puberty on gender-nonconforming youth, puberty suppression as “a reversible medical intervention” was introduced by Dutch clinicians in the early 2000s, Annelou L.C. de Vries, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“The aim of puberty suppression was to prevent the psychological suffering stemming from undesired physical changes when puberty starts and allowing the adolescent time to make plans regarding further transition or not,” Dr. de Vries said. “Following this rationale, younger age at the time of starting medical-affirming treatment (puberty suppression or hormones) would be expected to correlate with fewer psychological difficulties related to physical changes than older individuals,” which was confirmed in the current study.

However, clinicians should be cautious in offering puberty suppression at a younger age, in part because “despite the increased availability of gender-affirming medical interventions for younger ages in recent years, there has not been a proportional decline in older presenting youth with gender incongruence,” she said.

More data are needed on youth with postpuberty adolescent-onset transgender histories. The original Dutch studies on gender-affirming medical interventions note case histories describing “the complexities that may be associated with later-presenting transgender adolescents and describe that some eventually detransition,” Dr. de Vries explained.

Ultimately, prospective studies with longer follow-up data are needed to better inform clinicians in developing an individualized treatment plan for youth with gender incongruence, Dr. de Vries concluded.

Care barriers can include parents, access, insurance

The study authors describe the situation of gender-affirming medical care in teens perfectly, M. Brett Cooper, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health Dallas, said in an interview.

Given a variety of factors that need further exploration, “many youth often don’t end up seeking gender-affirming medical care until puberty has progressed to near full maturity,” he said. “The findings from this study provide preliminary evidence to show that if we can identify these youth earlier in their gender journey, we might be able to impact adverse mental health outcomes in a positive way.”

Dr. Cooper said he was not surprised by the study findings. “They are similar to what I see in my clinic.

“Many of our patients often don’t present for medical care until around age 15 or older, similar to the findings of the study,” he added. “The majority of our patients have had a diagnosis of anxiety or depression at some point in their lifetime, including inpatient hospitalizations for their mental health.”

One of the most important barriers to care often can be parents or guardians, said Dr. Cooper. “Young people usually know their gender identity by about age 4-5 but parents may think that a gender-diverse identity could simply be a ‘phase.’ Other times, young people may hide their identity out of fear of a negative reaction from their parents. The distress around identity may become more pronounced once pubertal changes, such as breast and testicle development, begin to worsen their dysphoria.”

“Another barrier to care can be the inability to find a competent, gender-affirming provider,” Dr. Cooper said. “Most large United States cities have at least one gender-affirming clinic, but for those youth who grow up in smaller towns, it may be difficult to access these clinics. In addition, some clinics require a letter from a therapist stating that the young person is transgender before they can be seen for medical care. This creates an access barrier, as it may be difficult not just to find a therapist but one who has experience working with gender-diverse youth.”

Insurance coverage, including lack thereof, is yet another barrier to care for transgender youth, said Dr. Cooper. “While many insurance companies have begun to cover medications such as testosterone and estrogen for gender-affirming care, many still have exclusions on things like puberty blockers and surgical interventions.” These interventions can be lifesaving, but financially prohibitive for many families if not covered by insurance.

As for the value of early timing of gender-affirming care, Dr. Cooper agreed with the study findings that the earlier that a young person can get into medical care for their gender identity, the better chance there is to reduce the prevalence of serious mental health outcomes. “This also prevents the potential development of secondary sexual characteristics, decreasing the need for or amount of surgery in the future if desired,” he said.

“More research is needed to better understand the reasons why many youth don’t present to care until later in puberty. In addition, we need better research on interventions that are effective at reducing serious mental health events in transgender and gender diverse youth,” Dr. Cooper stated. “Another area that I would like to see researched is looking at the mental health of non-Caucasian youth. As the authors noted in their study, many clinics have a high percentage of patients presenting for care who identify as White or Caucasian, and we need to better understand why these other youth are not presenting for care.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Sorbara disclosed salary support from the Canadian Pediatric Endocrine Group fellowship program. Dr. de Vries had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cooper had no financial conflicts to disclose, and serves as a contributor to LGBTQ Youth Consult in Pediatric News.

SOURCES: Sorbara JC et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3600; de Vries ALC et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-010611.

Gender-incongruent youth who present for gender-affirming medical care later in adolescence have higher rates of mental health problems than their younger counterparts, based on data from a review of 300 individuals.

“Puberty is a vulnerable time for youth with gender dysphoria because distress may intensify with the development of secondary sex characteristics corresponding to the assigned rather than the experienced gender,” wrote Julia C. Sorbara, MD, of the University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children, also in Toronto, and colleagues.

Although gender-affirming medical care (GAMC) in the form of hormone blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones early in puberty can decrease in emotional and behavioral problems, many teens present later in puberty, and the relationship between pubertal stage at presentation for treatment and mental health has not been examined, they wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from youth with gender incongruence who were seen at a single center; 116 were younger than 15 years at presentation for GAMC and were defined as younger-presenting youth (YPY), and 184 patients aged 15 years and older were defined as older-presenting youth (OPY).

Overall, 78% of the youth reported at least one mental health problem at their initial visit. Significantly more OPY than YPY reported diagnosed depression (46% vs. 30%), self-harm (40% vs. 28%), suicidal thoughts (52% vs. 40%), suicide attempts (17% vs. 9%), and use of psychoactive medications (36% vs. 23%), all with P < .05.

In a multivariate analysis, patients in Tanner stages 4 and 5 were five times more likely to experience depressive disorders (odds ratio, 5.49) and four times as likely to experience depressive disorders (OR, 4.18) as those in earlier Tanner stages. Older age remained significantly associated with use of psychoactive medications (OR, 1.31), but not with anxiety or depression, the researchers wrote.

The YPY group were significantly younger at the age of recognizing gender incongruence, compared with the OPY group, with median ages at recognition of 5.8 years and 9 years, respectively, and younger patients came out about their gender identity at an average of 12 years, compared with 15 years for older patients.

The quantitative data are among the first to relate pubertal stage to mental health in gender-incongruent youth, “supporting clinical observations that pubertal development, menses, and erections are distressing to these youth and consistent with the beneficial role of pubertal suppression, even when used as monotherapy without gender-affirming hormones,” Dr. Sorbara and associates wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and the collection of mental health data at only one time point and by the use of self-reports. However, the results suggest that “[gender-incongruent] youth who present to GAMC later in life are a particularly high-risk subset of a vulnerable population,” they noted. “Further study is required to better describe the mental health trajectories of transgender youth and determine if mental health status or age at initiation of GAMC is correlated with psychological well-being in adulthood.”

Don’t rush to puberty suppression in younger teens

To reduce the stress of puberty on gender-nonconforming youth, puberty suppression as “a reversible medical intervention” was introduced by Dutch clinicians in the early 2000s, Annelou L.C. de Vries, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“The aim of puberty suppression was to prevent the psychological suffering stemming from undesired physical changes when puberty starts and allowing the adolescent time to make plans regarding further transition or not,” Dr. de Vries said. “Following this rationale, younger age at the time of starting medical-affirming treatment (puberty suppression or hormones) would be expected to correlate with fewer psychological difficulties related to physical changes than older individuals,” which was confirmed in the current study.

However, clinicians should be cautious in offering puberty suppression at a younger age, in part because “despite the increased availability of gender-affirming medical interventions for younger ages in recent years, there has not been a proportional decline in older presenting youth with gender incongruence,” she said.

More data are needed on youth with postpuberty adolescent-onset transgender histories. The original Dutch studies on gender-affirming medical interventions note case histories describing “the complexities that may be associated with later-presenting transgender adolescents and describe that some eventually detransition,” Dr. de Vries explained.

Ultimately, prospective studies with longer follow-up data are needed to better inform clinicians in developing an individualized treatment plan for youth with gender incongruence, Dr. de Vries concluded.

Care barriers can include parents, access, insurance

The study authors describe the situation of gender-affirming medical care in teens perfectly, M. Brett Cooper, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health Dallas, said in an interview.

Given a variety of factors that need further exploration, “many youth often don’t end up seeking gender-affirming medical care until puberty has progressed to near full maturity,” he said. “The findings from this study provide preliminary evidence to show that if we can identify these youth earlier in their gender journey, we might be able to impact adverse mental health outcomes in a positive way.”

Dr. Cooper said he was not surprised by the study findings. “They are similar to what I see in my clinic.

“Many of our patients often don’t present for medical care until around age 15 or older, similar to the findings of the study,” he added. “The majority of our patients have had a diagnosis of anxiety or depression at some point in their lifetime, including inpatient hospitalizations for their mental health.”

One of the most important barriers to care often can be parents or guardians, said Dr. Cooper. “Young people usually know their gender identity by about age 4-5 but parents may think that a gender-diverse identity could simply be a ‘phase.’ Other times, young people may hide their identity out of fear of a negative reaction from their parents. The distress around identity may become more pronounced once pubertal changes, such as breast and testicle development, begin to worsen their dysphoria.”

“Another barrier to care can be the inability to find a competent, gender-affirming provider,” Dr. Cooper said. “Most large United States cities have at least one gender-affirming clinic, but for those youth who grow up in smaller towns, it may be difficult to access these clinics. In addition, some clinics require a letter from a therapist stating that the young person is transgender before they can be seen for medical care. This creates an access barrier, as it may be difficult not just to find a therapist but one who has experience working with gender-diverse youth.”

Insurance coverage, including lack thereof, is yet another barrier to care for transgender youth, said Dr. Cooper. “While many insurance companies have begun to cover medications such as testosterone and estrogen for gender-affirming care, many still have exclusions on things like puberty blockers and surgical interventions.” These interventions can be lifesaving, but financially prohibitive for many families if not covered by insurance.

As for the value of early timing of gender-affirming care, Dr. Cooper agreed with the study findings that the earlier that a young person can get into medical care for their gender identity, the better chance there is to reduce the prevalence of serious mental health outcomes. “This also prevents the potential development of secondary sexual characteristics, decreasing the need for or amount of surgery in the future if desired,” he said.

“More research is needed to better understand the reasons why many youth don’t present to care until later in puberty. In addition, we need better research on interventions that are effective at reducing serious mental health events in transgender and gender diverse youth,” Dr. Cooper stated. “Another area that I would like to see researched is looking at the mental health of non-Caucasian youth. As the authors noted in their study, many clinics have a high percentage of patients presenting for care who identify as White or Caucasian, and we need to better understand why these other youth are not presenting for care.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Sorbara disclosed salary support from the Canadian Pediatric Endocrine Group fellowship program. Dr. de Vries had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cooper had no financial conflicts to disclose, and serves as a contributor to LGBTQ Youth Consult in Pediatric News.

SOURCES: Sorbara JC et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3600; de Vries ALC et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-010611.

Gender-incongruent youth who present for gender-affirming medical care later in adolescence have higher rates of mental health problems than their younger counterparts, based on data from a review of 300 individuals.

“Puberty is a vulnerable time for youth with gender dysphoria because distress may intensify with the development of secondary sex characteristics corresponding to the assigned rather than the experienced gender,” wrote Julia C. Sorbara, MD, of the University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Children, also in Toronto, and colleagues.

Although gender-affirming medical care (GAMC) in the form of hormone blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones early in puberty can decrease in emotional and behavioral problems, many teens present later in puberty, and the relationship between pubertal stage at presentation for treatment and mental health has not been examined, they wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from youth with gender incongruence who were seen at a single center; 116 were younger than 15 years at presentation for GAMC and were defined as younger-presenting youth (YPY), and 184 patients aged 15 years and older were defined as older-presenting youth (OPY).

Overall, 78% of the youth reported at least one mental health problem at their initial visit. Significantly more OPY than YPY reported diagnosed depression (46% vs. 30%), self-harm (40% vs. 28%), suicidal thoughts (52% vs. 40%), suicide attempts (17% vs. 9%), and use of psychoactive medications (36% vs. 23%), all with P < .05.

In a multivariate analysis, patients in Tanner stages 4 and 5 were five times more likely to experience depressive disorders (odds ratio, 5.49) and four times as likely to experience depressive disorders (OR, 4.18) as those in earlier Tanner stages. Older age remained significantly associated with use of psychoactive medications (OR, 1.31), but not with anxiety or depression, the researchers wrote.

The YPY group were significantly younger at the age of recognizing gender incongruence, compared with the OPY group, with median ages at recognition of 5.8 years and 9 years, respectively, and younger patients came out about their gender identity at an average of 12 years, compared with 15 years for older patients.

The quantitative data are among the first to relate pubertal stage to mental health in gender-incongruent youth, “supporting clinical observations that pubertal development, menses, and erections are distressing to these youth and consistent with the beneficial role of pubertal suppression, even when used as monotherapy without gender-affirming hormones,” Dr. Sorbara and associates wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the cross-sectional design and the collection of mental health data at only one time point and by the use of self-reports. However, the results suggest that “[gender-incongruent] youth who present to GAMC later in life are a particularly high-risk subset of a vulnerable population,” they noted. “Further study is required to better describe the mental health trajectories of transgender youth and determine if mental health status or age at initiation of GAMC is correlated with psychological well-being in adulthood.”

Don’t rush to puberty suppression in younger teens

To reduce the stress of puberty on gender-nonconforming youth, puberty suppression as “a reversible medical intervention” was introduced by Dutch clinicians in the early 2000s, Annelou L.C. de Vries, MD, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“The aim of puberty suppression was to prevent the psychological suffering stemming from undesired physical changes when puberty starts and allowing the adolescent time to make plans regarding further transition or not,” Dr. de Vries said. “Following this rationale, younger age at the time of starting medical-affirming treatment (puberty suppression or hormones) would be expected to correlate with fewer psychological difficulties related to physical changes than older individuals,” which was confirmed in the current study.

However, clinicians should be cautious in offering puberty suppression at a younger age, in part because “despite the increased availability of gender-affirming medical interventions for younger ages in recent years, there has not been a proportional decline in older presenting youth with gender incongruence,” she said.

More data are needed on youth with postpuberty adolescent-onset transgender histories. The original Dutch studies on gender-affirming medical interventions note case histories describing “the complexities that may be associated with later-presenting transgender adolescents and describe that some eventually detransition,” Dr. de Vries explained.

Ultimately, prospective studies with longer follow-up data are needed to better inform clinicians in developing an individualized treatment plan for youth with gender incongruence, Dr. de Vries concluded.

Care barriers can include parents, access, insurance

The study authors describe the situation of gender-affirming medical care in teens perfectly, M. Brett Cooper, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center/Children’s Health Dallas, said in an interview.

Given a variety of factors that need further exploration, “many youth often don’t end up seeking gender-affirming medical care until puberty has progressed to near full maturity,” he said. “The findings from this study provide preliminary evidence to show that if we can identify these youth earlier in their gender journey, we might be able to impact adverse mental health outcomes in a positive way.”

Dr. Cooper said he was not surprised by the study findings. “They are similar to what I see in my clinic.

“Many of our patients often don’t present for medical care until around age 15 or older, similar to the findings of the study,” he added. “The majority of our patients have had a diagnosis of anxiety or depression at some point in their lifetime, including inpatient hospitalizations for their mental health.”

One of the most important barriers to care often can be parents or guardians, said Dr. Cooper. “Young people usually know their gender identity by about age 4-5 but parents may think that a gender-diverse identity could simply be a ‘phase.’ Other times, young people may hide their identity out of fear of a negative reaction from their parents. The distress around identity may become more pronounced once pubertal changes, such as breast and testicle development, begin to worsen their dysphoria.”

“Another barrier to care can be the inability to find a competent, gender-affirming provider,” Dr. Cooper said. “Most large United States cities have at least one gender-affirming clinic, but for those youth who grow up in smaller towns, it may be difficult to access these clinics. In addition, some clinics require a letter from a therapist stating that the young person is transgender before they can be seen for medical care. This creates an access barrier, as it may be difficult not just to find a therapist but one who has experience working with gender-diverse youth.”

Insurance coverage, including lack thereof, is yet another barrier to care for transgender youth, said Dr. Cooper. “While many insurance companies have begun to cover medications such as testosterone and estrogen for gender-affirming care, many still have exclusions on things like puberty blockers and surgical interventions.” These interventions can be lifesaving, but financially prohibitive for many families if not covered by insurance.

As for the value of early timing of gender-affirming care, Dr. Cooper agreed with the study findings that the earlier that a young person can get into medical care for their gender identity, the better chance there is to reduce the prevalence of serious mental health outcomes. “This also prevents the potential development of secondary sexual characteristics, decreasing the need for or amount of surgery in the future if desired,” he said.

“More research is needed to better understand the reasons why many youth don’t present to care until later in puberty. In addition, we need better research on interventions that are effective at reducing serious mental health events in transgender and gender diverse youth,” Dr. Cooper stated. “Another area that I would like to see researched is looking at the mental health of non-Caucasian youth. As the authors noted in their study, many clinics have a high percentage of patients presenting for care who identify as White or Caucasian, and we need to better understand why these other youth are not presenting for care.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Sorbara disclosed salary support from the Canadian Pediatric Endocrine Group fellowship program. Dr. de Vries had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Cooper had no financial conflicts to disclose, and serves as a contributor to LGBTQ Youth Consult in Pediatric News.

SOURCES: Sorbara JC et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3600; de Vries ALC et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-010611.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Chronic, nonhealing leg ulcer

An 80-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, psoriasis vulgaris with associated pruritus, and well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a slowly enlarging ulceration on her left leg of 1 year’s duration. She noted that this lesion healed less rapidly than previous stasis leg ulcerations, despite using the same treatment approach that included dressings, elevation, and diuretics to decrease pedal edema.

Physical examination revealed plaques with white micaceous scaling over her extensor surfaces and scalp, as well as guttate lesions on the trunk, typical of psoriasis vulgaris. A 5.8 × 7.2-cm malodorous ulceration was superimposed on a large psoriatic plaque on her left anterior lower leg (FIGURE 1). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained from the peripheral margin.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Basal cell carcinoma

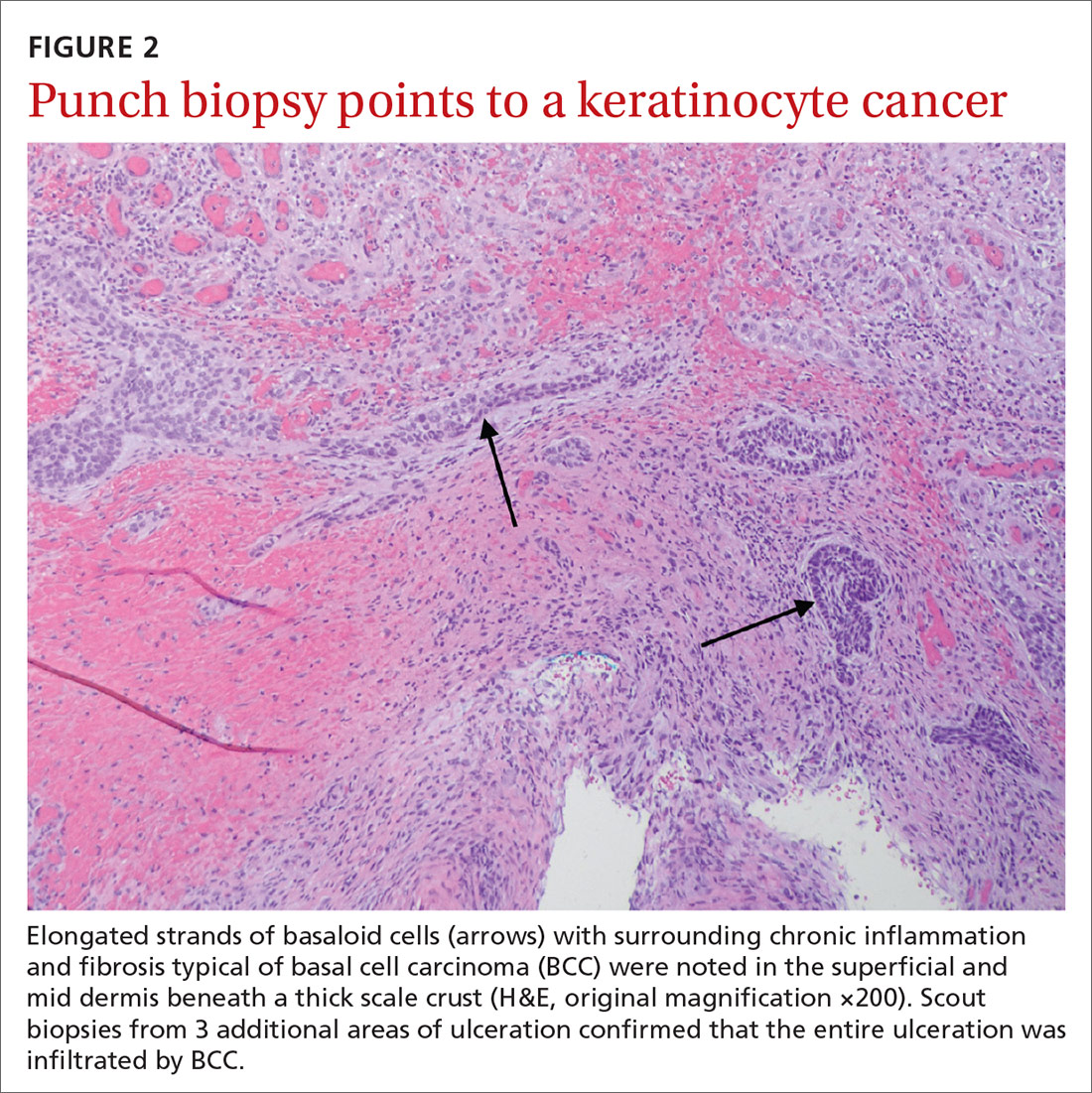

Histopathological examination revealed elongated strands of closely packed basaloid cells embedded in a dense fibrous stroma with overlying ulceration and crusting (FIGURE 2). Immunohistochemical staining with cytokeratin (CK) 5/6 decorated the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, which confirmed that the tumor was a keratinocyte cancer. CK 20 was negative, excluding the possibility of a Merkel cell carcinoma. Scout biopsies from 3 additional areas of ulceration confirmed that the entire ulceration was infiltrated by basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

A surprise hidden in a chronic ulcer

More than 6 million Americans have chronic ulcers and most occur on the legs.1 The majority of these chronic ulcerations are etiologically related to venous stasis, arterial insufficiency, or neuropathy.2

Bacterial pyoderma, chronic infection caused by atypical acid-fast bacilli or deep fungal infection, pyoderma gangrenosum, cutaneous vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and venous ulceration were all considered to explain this patient’s nonhealing wound. A biopsy was required to fully assess these possibilities.

Don’t overlook the possibility of malignancy. In a cross-sectional, multicenter study by Senet et al,3 144 patients with 154 total chronic leg ulcers were evaluated in tertiary care centers for malignancy, which was found to occur at a rate of 10.4%. Similarly, Ghasemi et al4 demonstrated a malignancy rate of 16.1% in 124 patients who underwent biopsy; the anterior shin was determined to be the most frequent location for malignancy. The most common skin cancer identified within the setting of chronic ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma.3 Although rare, there are reports of BCC identified in chronic wounds.3-7

Morphological signs suggestive of malignancy in chronic ulcerations include hyperkeratosis, granulation tissue surrounded by a raised border, unusual pain or bleeding, and increased tissue friability. Our patient had none of these signs and symptoms. However, it is possible that she had a tumor that ulcerated and would not heal.

Continue to: Which came first?

Which came first? It’s difficult to know in this case whether a persistent BCC ulcerated, forming this lesion, or if scarring associated with a chronic ulceration led to the development of the BCC.6 Based on biopsies taken at an earlier date, Schnirring-Judge and Belpedio7 concluded that a chronic leg ulcer could, indeed, transform into a BCC; however, pre-existing BCC more commonly ulcerates and then does not heal.

Treatment options

While smaller, superficial BCCs can be treated with topical imiquimod, photodynamic therapy, or electrodesiccation and curettage, larger lesions should be treated with Mohs micrographic surgery and excisional surgery with grafting. Inoperable tumors may be treated with radiation therapy and vismodegib.

Our patient. Once the diagnosis of BCC was established, treatment options were discussed, including excision, local radiation therapy, and oral hedgehog inhibitor drug therapy.8 Our patient opted to undergo a wide local excision of the lesion followed by negative-pressure wound therapy, which led to complete healing.

CORRESPONDENCE

David Crasto, DO, William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine, 498 Tuscan Avenue, Hattiesburg, MS 39401; crastodave@gmail.com

1. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, et al. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763-771.