User login

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Educating Medical Students About Dementia Assessment and Treatment Planning

The global burden of dementia is increasing at an alarming pace and is estimated to soon affect 81 million individuals worldwide.1 The World Health Organization and the Institute of Medicine have recommended greater dementia awareness and education.2,3 Despite this emphasis on dementia education, many general practitioners consider dementia care beyond their clinical domain and feel that specialists, such as geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, or neurologists should address dementia assessment and treatment. 4 Unfortunately, the geriatric health care workforce has been shrinking. The American Geriatrics Society estimates the need for 30,000 geriatricians by 2030, although there are only 7,300 board-certified geriatricians currently in the US.5 There is an urgent need for educating all medical trainees in dementia care regardless of their specialization interest. As the largest underwriter of graduate medical education in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is well placed for rolling out focused dementia education. Training needs to be practical, brief, and responsive to knowledge gaps to reach the most trainees.

Despite growing emphasis on geriatric training, many medical students have limited experience with patients with dementia or their caregivers, lack exposure to interdisciplinary teams, have a poor attitude toward geriatric patients, and display specific knowledge gaps in dementia assessment and management. 6-9 Other knowledge gaps noted in medical students included assessing behavioral problems, function, safety, and caregiver burden. Medical students also had limited exposure to interdisciplinary team dementia assessment and management.

Our goal was to develop a multicomponent, experiential, brief curriculum using team-based learning to expose senior medical students to interdisciplinary assessment of dementia. The curriculum was developed with input from the interdisciplinary team to address dementia knowledge gaps while providing an opportunity to interact with caregivers. The curriculum targeted all medical students regardless of their interest in geriatrics. Particular emphasis was placed on systems-based learning and the importance of teamwork in managing complex conditions such as dementia. Students were taught that incorporating interdisciplinary input would be more effective during dementia care planning rather than developing specialized knowledge.

Methods

Our team developed a curriculum for fourthyear medical students who rotated through the VA Memory Disorders Clinic as a part of their geriatric medicine clerkship at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. The Memory Disorders Clinic is a consultation practice at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) where patients with memory problems are evaluated by a team consisting of a geriatric psychiatrist, a geriatrician, a social worker, and a neuropsychologist. Each specialist addresses specific areas of dementia assessment and management. The curriculum included didactics, clinical experience, and team-based learning.

Didactics

An hour-long didactic session lead by the team geriatrician provided a general overview of interdisciplinary assessment of dementia to groups of 2 to 3 students at a time. The geriatrician presented an overview of dementia types, comorbidities, medications that affect memory, details of the physical examination, and laboratory, cognitive, and behavioral assessments along with treatment plan development. Students also learned about the roles of the social worker, geriatrician, neuropsychologist, and geriatric psychiatrist in the clinic. Pictographs and pie charts highlighted the role of disciplines in assessing and managing aspects of dementia.

The social work evaluation included advance care planning, functional assessment, safety assessment (driving, guns, wandering behaviors, etc), home safety evaluation, support system, and financial evaluation. Each medical student received a binder with local resources to become familiar with the depth and breadth of agencies involved in dementia care. Each medical student learned how to administer the Zarit Burden Scale to assess caregiver burden.10 The details of the geriatrician assessment included reviewing medical comorbidities and medications contributing to dementia, a physical examination, including a focused neurologic examination, laboratory assessment, and judicious use of neuroimaging.

The neuropsychology assessment education included a battery of tests and assessments. The global screening instruments included the Modified Mini-Mental State examination (3MS), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (SLUMS).11-13 Executive function is evaluated using the Trails Making Test A and Trails Making Test B, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Semantic Fluency Test, and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status test. Cognitive tests were compared and age- , education-, and race-adjusted norms for rating scales were listed if available. Each student was expected to show proficiency in ≥ 2 cognitive screening instruments (3MS, MoCA, or SLUMS). The geriatric psychiatry assessment included clinical history, onset, and course of memory problems from patient and caregiver perspectives, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory for assessing behavioral problems, employing the clinical dementia rating scale, integrating the team data, summarizing assessment, and formulating a treatment plan.14

Clinical

Students had a single clinical exposure. Students followed 1 patient and his or her caregiver through the team assessment and observed each provider’s assessment to learn interview techniques to adapt to the patient’s sensory or cognitive impairment and become familiar with different tools and devices used in the dementia clinic, such as hearing amplifiers. Each specialist provided hands-on experience. This encounter helped the students connect with caregivers and appreciate their role in patient care.

Systems learning was an important component integrated throughout the clinical experience. Examples include using video teleconferences to communicate findings among team members and electronic health records to seamlessly obtain and integrate data. Students learned how to create worksheets to graph laboratory data such as B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and rapid plasma regain levels. Student gained experience in using applications to retrieve neuroimaging data, results of sleep studies, and other data. Many patients had not received the results of their sleep study, and students had the responsibility to share these reports, including the number of apneic episodes. Students used the VA Computerized Patient Record System for reviewing patient records. One particularly useful tool was Joint Legacy Viewer, a remote access tool used to retrieve data on veterans from anywhere within the US. Students were also trained on medication and consult order menus in the system.

Team-Based

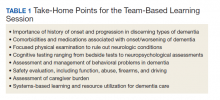

Learning The objectives of the team-based learning section were to teach students basic concepts of integrating the interdisciplinary assessment and formulating a treatment plan, to provide an opportunity to present their case in a group format, to discuss the differential diagnosis, management and treatment plan with a geriatrician in the team-based learning format, and to answer questions from other students. The instructors developed a set of prepared take-home points (Table 1). The team-based learning sessions were structured so that all take-home points were covered.

Evaluations

Evaluations were performed before and immediately after the clinical experience. In preevaluation, students reported the frequency of their participation in an interdisciplinary team assessment of any condition and specifically for dementia. In pre- and postevaluation, students rated their perception of the role of interdisciplinary team members in assessing and managing dementia, their personal abilities to assess cognition, behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and their perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care. A Likert scale (poor = 1; fair = 2; good = 3; very good = 4; and excellent = 5) was employed (eApendices 1 and 2 can be found at doi:10.12788/fp.0052). The only demographic information collected was the student’s gender. Semistructured interviews were conducted to assess students’ current knowledge, experience, and needs. These interviews lasted about 20 minutes and collected information regarding the students’ knowledge about cognitive and behavioral problems in general and those occurring in dementia, their experience with screening, and any problems they encountered.

Statistical Analysis

Student baseline characteristics were assessed. Pre- and postassessments were analyzed with the McNemar test for paired data, and associations with experience were evaluated using χ2 tests. Ratings were dichotomized as very good/excellent vs poor/fair/ good because our educational goal was “very good” to “excellent” experience in dementia care and to avoid expected small cell counts. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide v5.1.

Results

One hundred fourth-year medical students participated, including 54 women. Thirtysix percent reported they had not previously attended an interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia, while 18% stated that they had attended only 1 interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia.

Before the education, students rated their dementia ability as poor. Only 2% (1 of 54), of those with 0 to 1 assessment experience rated their ability for assessing dementia with an interdisciplinary team format as very good/excellent compared with 20% (9/46) of those previously attending ≥ 2 assessments (P = .03); other ratings of ability were not associated with prior experience.

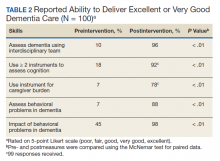

There was a significant change in the students’ self-efficacy ratings pre- to postassessment (P < .05) (Table 2). Only 10% rated their ability to assess for dementia as very good/excellent in before the intervention compared with 96% in postassessment (P < .01). Students’ perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care improved significantly (45% to 98%, P < .01). Similarly, student’s perception of their ability to assess behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and cognition improved significantly from 7 to 88%; 7 to 78%, and 18 to 92%, respectively (P < .01). Students perception of the role of social worker, neuropsychologist, geriatrician, and geriatric psychiatrist also improved significantly for most measures from 81 to 98% (P = .02), 87 to 98% (P = .05), 94 to 99% (P = .06), and 88 to 100% (P = .01), respectively.

The semistructured interviews revealed that awareness of behavioral problems associated with dementia varied for different behavioral problems. Although many students showed familiarity with depression, agitation, and psychosis, they were not comfortable assessing them in a patient with dementia. These students were less aware of other behavioral problems such as disinhibition, apathy, and movement disorders. Deficits were noted in the skill of administering commonly used global cognitive screens, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).15

In semistructured interviews, only 7% of senior medical students were comfortable assessing behavioral problems associated with dementia. Most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms. Similarly, only 7% of students were comfortable assessing caregiver burden, and most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess caregiver burden. Only 1 in 5 students were comfortable using 2 cognitive screens to assess cognitive deficits. Many students stated that they were not routinely expected to perform common cognitive screens, such as the MMSE during their medical training except students who had expressed an interest in psychiatry and were expected to be proficient in the MMSE. Most students were making common mistakes, such as converting the 3-command task to 3 individual single commands, helping too much with serial 7s, and giving too much positive feedback throughout the test.

Discussion

Significant knowledge gaps regarding dementia were found in our study, which is in keeping with other studies in the area. Dementia knowledge deficits among medical trainees have been identified in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the US.6-9

In our study, a brief multicomponent experiential curriculum improved senior medical students’ perception and self-efficacy in diagnosing dementia. This is in keeping with other studies, such as the PAIRS Program.7 Findings from another study indicated that education for geriatric- oriented physicians should focus on experiential learning components through observation and interaction with older adults.16

A background of direct experience with older adults is associated with more positive attitudes toward older adults and increased interest in geriatric medicine.16 In our study, the exposure was brief; therefore, the results could not be compared with other long-term exposure studies. However, even with this brief intervention most students reported being comfortable with assessing caregiver burden (78%), behavioral problems of dementia (88%), and using ≥ 2 cognitive screens (92%). Comfortable in dementia assessment increased after the intervention from 10% to 96%. This finding is encouraging because brief multicomponent dementia education can be devised easily. This finding needs to be taken with caution because we did not conduct a formal skills evaluation.

A unique component of our experience was to learn medical students’ perception about the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on the trajectory, outcomes, and management of dementia. These symptoms included delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite and eating. Less than half the students thought that neuropsychiatric symptoms had a significant impact on dementia before the experience. Through didactics, systematic assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and interaction with caregivers, > 98% of students learned that these symptoms have a significant impact on dementia management.

This experience also emphasized the role of several disciplines in dementia assessment and management. Students’ experience positively influenced appreciation of the role of the memory clinic team. Our hope is that students will seek input from social workers, neuropsychologists, and other team members when working with patients with dementia or their caregivers. The common reason why primary care physicians focus on an exclusive medical model is the time commitment for communicating with an interdisciplinary team. Students experienced the feasibility of the interdisciplinary team involvement and how technology could be used for synchronous and asynchronous communication among team members. Medical students also were introduced to complex billing codes used when ≥ 3 disciplines assess/manage a geriatric patient.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of long-term follow-up evaluations, no metrics for practice changes clinical outcomes, and implementation in a single medical school. The postexperience evaluation in this study was performed immediately after the intervention. Long-term follow-up would inform whether the changes noted are durable. Because of the brief nature of our intervention, we do not believe that it would change practice in clinical care. It will be informative to follow this cohort of students to study whether their clinical approach to dementia care changes. The intervention needs to be replicated in other medical schools and in more heterogeneous groups to generalize the results of the study.

Conclusions

Senior medical students are not routinely exposed to interdisciplinary team assessments. Dementia knowledge gaps were prevalent in this cohort of senior medical students. Providing interdisciplinary geriatric educational experience improved their perception of their ability to assess for dementia and their recognition of the roles of interdisciplinary team members. Plans are in place to continue and expand the program to other complex geriatric syndromes.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society. Oral presentation at the same meeting as part of the select Geriatric Education Methods and Materials Swap workshop.

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

2. Janca A, Aarli JA, Prilipko L, Dua T, Saxena S, Saraceno B. WHO/WFN survey of neurological services: a worldwide perspective. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247(1):29-34. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.03.003

3. Wilkins KM, Blazek MC, Brooks WB, Lehmann SW, Popeo D, Wagenaar D. Six things all medical students need to know about geriatric psychiatry (and how to teach them). Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):693-700. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0691-7

4. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461- 467. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh140

5. Lester PE, Dharmarajan TS, Weinstein E. The looming geriatrician shortage: ramifications and solutions. J Aging Health. 2019:898264319879325. doi:10.1177/0898264319879325

6. Struck BD, Bernard MA, Teasdale TA; Oklahoma University Geriatric Education G. Effect of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on third-year students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):2007-2011. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00473.x

7. Jefferson AL, Cantwell NG, Byerly LK, Morhardt D. Medical student education program in Alzheimer’s disease: the PAIRS Program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:80. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-80

8. Nagle BJ, Usita PM, Edland SD. United States medical students’ knowledge of Alzheimer disease. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:4. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.4

9. Scott TL, Kugelman M, Tulloch K. How medical professional students view older people with dementia: Implications for education and practice. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225329.

10. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649

11. McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377-383. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7

12. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Ger iatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

13. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, 3rd, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86

14. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

15. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

16. Fitzgerald JT, Wray LA, Halter JB, Williams BC, Supiano MA. Relating medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and experience to an interest in geriatric medicine. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):849-855. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.849

The global burden of dementia is increasing at an alarming pace and is estimated to soon affect 81 million individuals worldwide.1 The World Health Organization and the Institute of Medicine have recommended greater dementia awareness and education.2,3 Despite this emphasis on dementia education, many general practitioners consider dementia care beyond their clinical domain and feel that specialists, such as geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, or neurologists should address dementia assessment and treatment. 4 Unfortunately, the geriatric health care workforce has been shrinking. The American Geriatrics Society estimates the need for 30,000 geriatricians by 2030, although there are only 7,300 board-certified geriatricians currently in the US.5 There is an urgent need for educating all medical trainees in dementia care regardless of their specialization interest. As the largest underwriter of graduate medical education in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is well placed for rolling out focused dementia education. Training needs to be practical, brief, and responsive to knowledge gaps to reach the most trainees.

Despite growing emphasis on geriatric training, many medical students have limited experience with patients with dementia or their caregivers, lack exposure to interdisciplinary teams, have a poor attitude toward geriatric patients, and display specific knowledge gaps in dementia assessment and management. 6-9 Other knowledge gaps noted in medical students included assessing behavioral problems, function, safety, and caregiver burden. Medical students also had limited exposure to interdisciplinary team dementia assessment and management.

Our goal was to develop a multicomponent, experiential, brief curriculum using team-based learning to expose senior medical students to interdisciplinary assessment of dementia. The curriculum was developed with input from the interdisciplinary team to address dementia knowledge gaps while providing an opportunity to interact with caregivers. The curriculum targeted all medical students regardless of their interest in geriatrics. Particular emphasis was placed on systems-based learning and the importance of teamwork in managing complex conditions such as dementia. Students were taught that incorporating interdisciplinary input would be more effective during dementia care planning rather than developing specialized knowledge.

Methods

Our team developed a curriculum for fourthyear medical students who rotated through the VA Memory Disorders Clinic as a part of their geriatric medicine clerkship at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. The Memory Disorders Clinic is a consultation practice at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) where patients with memory problems are evaluated by a team consisting of a geriatric psychiatrist, a geriatrician, a social worker, and a neuropsychologist. Each specialist addresses specific areas of dementia assessment and management. The curriculum included didactics, clinical experience, and team-based learning.

Didactics

An hour-long didactic session lead by the team geriatrician provided a general overview of interdisciplinary assessment of dementia to groups of 2 to 3 students at a time. The geriatrician presented an overview of dementia types, comorbidities, medications that affect memory, details of the physical examination, and laboratory, cognitive, and behavioral assessments along with treatment plan development. Students also learned about the roles of the social worker, geriatrician, neuropsychologist, and geriatric psychiatrist in the clinic. Pictographs and pie charts highlighted the role of disciplines in assessing and managing aspects of dementia.

The social work evaluation included advance care planning, functional assessment, safety assessment (driving, guns, wandering behaviors, etc), home safety evaluation, support system, and financial evaluation. Each medical student received a binder with local resources to become familiar with the depth and breadth of agencies involved in dementia care. Each medical student learned how to administer the Zarit Burden Scale to assess caregiver burden.10 The details of the geriatrician assessment included reviewing medical comorbidities and medications contributing to dementia, a physical examination, including a focused neurologic examination, laboratory assessment, and judicious use of neuroimaging.

The neuropsychology assessment education included a battery of tests and assessments. The global screening instruments included the Modified Mini-Mental State examination (3MS), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (SLUMS).11-13 Executive function is evaluated using the Trails Making Test A and Trails Making Test B, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Semantic Fluency Test, and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status test. Cognitive tests were compared and age- , education-, and race-adjusted norms for rating scales were listed if available. Each student was expected to show proficiency in ≥ 2 cognitive screening instruments (3MS, MoCA, or SLUMS). The geriatric psychiatry assessment included clinical history, onset, and course of memory problems from patient and caregiver perspectives, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory for assessing behavioral problems, employing the clinical dementia rating scale, integrating the team data, summarizing assessment, and formulating a treatment plan.14

Clinical

Students had a single clinical exposure. Students followed 1 patient and his or her caregiver through the team assessment and observed each provider’s assessment to learn interview techniques to adapt to the patient’s sensory or cognitive impairment and become familiar with different tools and devices used in the dementia clinic, such as hearing amplifiers. Each specialist provided hands-on experience. This encounter helped the students connect with caregivers and appreciate their role in patient care.

Systems learning was an important component integrated throughout the clinical experience. Examples include using video teleconferences to communicate findings among team members and electronic health records to seamlessly obtain and integrate data. Students learned how to create worksheets to graph laboratory data such as B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and rapid plasma regain levels. Student gained experience in using applications to retrieve neuroimaging data, results of sleep studies, and other data. Many patients had not received the results of their sleep study, and students had the responsibility to share these reports, including the number of apneic episodes. Students used the VA Computerized Patient Record System for reviewing patient records. One particularly useful tool was Joint Legacy Viewer, a remote access tool used to retrieve data on veterans from anywhere within the US. Students were also trained on medication and consult order menus in the system.

Team-Based

Learning The objectives of the team-based learning section were to teach students basic concepts of integrating the interdisciplinary assessment and formulating a treatment plan, to provide an opportunity to present their case in a group format, to discuss the differential diagnosis, management and treatment plan with a geriatrician in the team-based learning format, and to answer questions from other students. The instructors developed a set of prepared take-home points (Table 1). The team-based learning sessions were structured so that all take-home points were covered.

Evaluations

Evaluations were performed before and immediately after the clinical experience. In preevaluation, students reported the frequency of their participation in an interdisciplinary team assessment of any condition and specifically for dementia. In pre- and postevaluation, students rated their perception of the role of interdisciplinary team members in assessing and managing dementia, their personal abilities to assess cognition, behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and their perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care. A Likert scale (poor = 1; fair = 2; good = 3; very good = 4; and excellent = 5) was employed (eApendices 1 and 2 can be found at doi:10.12788/fp.0052). The only demographic information collected was the student’s gender. Semistructured interviews were conducted to assess students’ current knowledge, experience, and needs. These interviews lasted about 20 minutes and collected information regarding the students’ knowledge about cognitive and behavioral problems in general and those occurring in dementia, their experience with screening, and any problems they encountered.

Statistical Analysis

Student baseline characteristics were assessed. Pre- and postassessments were analyzed with the McNemar test for paired data, and associations with experience were evaluated using χ2 tests. Ratings were dichotomized as very good/excellent vs poor/fair/ good because our educational goal was “very good” to “excellent” experience in dementia care and to avoid expected small cell counts. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide v5.1.

Results

One hundred fourth-year medical students participated, including 54 women. Thirtysix percent reported they had not previously attended an interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia, while 18% stated that they had attended only 1 interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia.

Before the education, students rated their dementia ability as poor. Only 2% (1 of 54), of those with 0 to 1 assessment experience rated their ability for assessing dementia with an interdisciplinary team format as very good/excellent compared with 20% (9/46) of those previously attending ≥ 2 assessments (P = .03); other ratings of ability were not associated with prior experience.

There was a significant change in the students’ self-efficacy ratings pre- to postassessment (P < .05) (Table 2). Only 10% rated their ability to assess for dementia as very good/excellent in before the intervention compared with 96% in postassessment (P < .01). Students’ perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care improved significantly (45% to 98%, P < .01). Similarly, student’s perception of their ability to assess behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and cognition improved significantly from 7 to 88%; 7 to 78%, and 18 to 92%, respectively (P < .01). Students perception of the role of social worker, neuropsychologist, geriatrician, and geriatric psychiatrist also improved significantly for most measures from 81 to 98% (P = .02), 87 to 98% (P = .05), 94 to 99% (P = .06), and 88 to 100% (P = .01), respectively.

The semistructured interviews revealed that awareness of behavioral problems associated with dementia varied for different behavioral problems. Although many students showed familiarity with depression, agitation, and psychosis, they were not comfortable assessing them in a patient with dementia. These students were less aware of other behavioral problems such as disinhibition, apathy, and movement disorders. Deficits were noted in the skill of administering commonly used global cognitive screens, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).15

In semistructured interviews, only 7% of senior medical students were comfortable assessing behavioral problems associated with dementia. Most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms. Similarly, only 7% of students were comfortable assessing caregiver burden, and most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess caregiver burden. Only 1 in 5 students were comfortable using 2 cognitive screens to assess cognitive deficits. Many students stated that they were not routinely expected to perform common cognitive screens, such as the MMSE during their medical training except students who had expressed an interest in psychiatry and were expected to be proficient in the MMSE. Most students were making common mistakes, such as converting the 3-command task to 3 individual single commands, helping too much with serial 7s, and giving too much positive feedback throughout the test.

Discussion

Significant knowledge gaps regarding dementia were found in our study, which is in keeping with other studies in the area. Dementia knowledge deficits among medical trainees have been identified in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the US.6-9

In our study, a brief multicomponent experiential curriculum improved senior medical students’ perception and self-efficacy in diagnosing dementia. This is in keeping with other studies, such as the PAIRS Program.7 Findings from another study indicated that education for geriatric- oriented physicians should focus on experiential learning components through observation and interaction with older adults.16

A background of direct experience with older adults is associated with more positive attitudes toward older adults and increased interest in geriatric medicine.16 In our study, the exposure was brief; therefore, the results could not be compared with other long-term exposure studies. However, even with this brief intervention most students reported being comfortable with assessing caregiver burden (78%), behavioral problems of dementia (88%), and using ≥ 2 cognitive screens (92%). Comfortable in dementia assessment increased after the intervention from 10% to 96%. This finding is encouraging because brief multicomponent dementia education can be devised easily. This finding needs to be taken with caution because we did not conduct a formal skills evaluation.

A unique component of our experience was to learn medical students’ perception about the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on the trajectory, outcomes, and management of dementia. These symptoms included delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite and eating. Less than half the students thought that neuropsychiatric symptoms had a significant impact on dementia before the experience. Through didactics, systematic assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and interaction with caregivers, > 98% of students learned that these symptoms have a significant impact on dementia management.

This experience also emphasized the role of several disciplines in dementia assessment and management. Students’ experience positively influenced appreciation of the role of the memory clinic team. Our hope is that students will seek input from social workers, neuropsychologists, and other team members when working with patients with dementia or their caregivers. The common reason why primary care physicians focus on an exclusive medical model is the time commitment for communicating with an interdisciplinary team. Students experienced the feasibility of the interdisciplinary team involvement and how technology could be used for synchronous and asynchronous communication among team members. Medical students also were introduced to complex billing codes used when ≥ 3 disciplines assess/manage a geriatric patient.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of long-term follow-up evaluations, no metrics for practice changes clinical outcomes, and implementation in a single medical school. The postexperience evaluation in this study was performed immediately after the intervention. Long-term follow-up would inform whether the changes noted are durable. Because of the brief nature of our intervention, we do not believe that it would change practice in clinical care. It will be informative to follow this cohort of students to study whether their clinical approach to dementia care changes. The intervention needs to be replicated in other medical schools and in more heterogeneous groups to generalize the results of the study.

Conclusions

Senior medical students are not routinely exposed to interdisciplinary team assessments. Dementia knowledge gaps were prevalent in this cohort of senior medical students. Providing interdisciplinary geriatric educational experience improved their perception of their ability to assess for dementia and their recognition of the roles of interdisciplinary team members. Plans are in place to continue and expand the program to other complex geriatric syndromes.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society. Oral presentation at the same meeting as part of the select Geriatric Education Methods and Materials Swap workshop.

The global burden of dementia is increasing at an alarming pace and is estimated to soon affect 81 million individuals worldwide.1 The World Health Organization and the Institute of Medicine have recommended greater dementia awareness and education.2,3 Despite this emphasis on dementia education, many general practitioners consider dementia care beyond their clinical domain and feel that specialists, such as geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, or neurologists should address dementia assessment and treatment. 4 Unfortunately, the geriatric health care workforce has been shrinking. The American Geriatrics Society estimates the need for 30,000 geriatricians by 2030, although there are only 7,300 board-certified geriatricians currently in the US.5 There is an urgent need for educating all medical trainees in dementia care regardless of their specialization interest. As the largest underwriter of graduate medical education in the US, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is well placed for rolling out focused dementia education. Training needs to be practical, brief, and responsive to knowledge gaps to reach the most trainees.

Despite growing emphasis on geriatric training, many medical students have limited experience with patients with dementia or their caregivers, lack exposure to interdisciplinary teams, have a poor attitude toward geriatric patients, and display specific knowledge gaps in dementia assessment and management. 6-9 Other knowledge gaps noted in medical students included assessing behavioral problems, function, safety, and caregiver burden. Medical students also had limited exposure to interdisciplinary team dementia assessment and management.

Our goal was to develop a multicomponent, experiential, brief curriculum using team-based learning to expose senior medical students to interdisciplinary assessment of dementia. The curriculum was developed with input from the interdisciplinary team to address dementia knowledge gaps while providing an opportunity to interact with caregivers. The curriculum targeted all medical students regardless of their interest in geriatrics. Particular emphasis was placed on systems-based learning and the importance of teamwork in managing complex conditions such as dementia. Students were taught that incorporating interdisciplinary input would be more effective during dementia care planning rather than developing specialized knowledge.

Methods

Our team developed a curriculum for fourthyear medical students who rotated through the VA Memory Disorders Clinic as a part of their geriatric medicine clerkship at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. The Memory Disorders Clinic is a consultation practice at the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System (CAVHS) where patients with memory problems are evaluated by a team consisting of a geriatric psychiatrist, a geriatrician, a social worker, and a neuropsychologist. Each specialist addresses specific areas of dementia assessment and management. The curriculum included didactics, clinical experience, and team-based learning.

Didactics

An hour-long didactic session lead by the team geriatrician provided a general overview of interdisciplinary assessment of dementia to groups of 2 to 3 students at a time. The geriatrician presented an overview of dementia types, comorbidities, medications that affect memory, details of the physical examination, and laboratory, cognitive, and behavioral assessments along with treatment plan development. Students also learned about the roles of the social worker, geriatrician, neuropsychologist, and geriatric psychiatrist in the clinic. Pictographs and pie charts highlighted the role of disciplines in assessing and managing aspects of dementia.

The social work evaluation included advance care planning, functional assessment, safety assessment (driving, guns, wandering behaviors, etc), home safety evaluation, support system, and financial evaluation. Each medical student received a binder with local resources to become familiar with the depth and breadth of agencies involved in dementia care. Each medical student learned how to administer the Zarit Burden Scale to assess caregiver burden.10 The details of the geriatrician assessment included reviewing medical comorbidities and medications contributing to dementia, a physical examination, including a focused neurologic examination, laboratory assessment, and judicious use of neuroimaging.

The neuropsychology assessment education included a battery of tests and assessments. The global screening instruments included the Modified Mini-Mental State examination (3MS), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status examination (SLUMS).11-13 Executive function is evaluated using the Trails Making Test A and Trails Making Test B, Controlled Oral Word Association Test, Semantic Fluency Test, and Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status test. Cognitive tests were compared and age- , education-, and race-adjusted norms for rating scales were listed if available. Each student was expected to show proficiency in ≥ 2 cognitive screening instruments (3MS, MoCA, or SLUMS). The geriatric psychiatry assessment included clinical history, onset, and course of memory problems from patient and caregiver perspectives, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory for assessing behavioral problems, employing the clinical dementia rating scale, integrating the team data, summarizing assessment, and formulating a treatment plan.14

Clinical

Students had a single clinical exposure. Students followed 1 patient and his or her caregiver through the team assessment and observed each provider’s assessment to learn interview techniques to adapt to the patient’s sensory or cognitive impairment and become familiar with different tools and devices used in the dementia clinic, such as hearing amplifiers. Each specialist provided hands-on experience. This encounter helped the students connect with caregivers and appreciate their role in patient care.

Systems learning was an important component integrated throughout the clinical experience. Examples include using video teleconferences to communicate findings among team members and electronic health records to seamlessly obtain and integrate data. Students learned how to create worksheets to graph laboratory data such as B12, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and rapid plasma regain levels. Student gained experience in using applications to retrieve neuroimaging data, results of sleep studies, and other data. Many patients had not received the results of their sleep study, and students had the responsibility to share these reports, including the number of apneic episodes. Students used the VA Computerized Patient Record System for reviewing patient records. One particularly useful tool was Joint Legacy Viewer, a remote access tool used to retrieve data on veterans from anywhere within the US. Students were also trained on medication and consult order menus in the system.

Team-Based

Learning The objectives of the team-based learning section were to teach students basic concepts of integrating the interdisciplinary assessment and formulating a treatment plan, to provide an opportunity to present their case in a group format, to discuss the differential diagnosis, management and treatment plan with a geriatrician in the team-based learning format, and to answer questions from other students. The instructors developed a set of prepared take-home points (Table 1). The team-based learning sessions were structured so that all take-home points were covered.

Evaluations

Evaluations were performed before and immediately after the clinical experience. In preevaluation, students reported the frequency of their participation in an interdisciplinary team assessment of any condition and specifically for dementia. In pre- and postevaluation, students rated their perception of the role of interdisciplinary team members in assessing and managing dementia, their personal abilities to assess cognition, behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and their perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care. A Likert scale (poor = 1; fair = 2; good = 3; very good = 4; and excellent = 5) was employed (eApendices 1 and 2 can be found at doi:10.12788/fp.0052). The only demographic information collected was the student’s gender. Semistructured interviews were conducted to assess students’ current knowledge, experience, and needs. These interviews lasted about 20 minutes and collected information regarding the students’ knowledge about cognitive and behavioral problems in general and those occurring in dementia, their experience with screening, and any problems they encountered.

Statistical Analysis

Student baseline characteristics were assessed. Pre- and postassessments were analyzed with the McNemar test for paired data, and associations with experience were evaluated using χ2 tests. Ratings were dichotomized as very good/excellent vs poor/fair/ good because our educational goal was “very good” to “excellent” experience in dementia care and to avoid expected small cell counts. Two-sided P < .05 indicated statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide v5.1.

Results

One hundred fourth-year medical students participated, including 54 women. Thirtysix percent reported they had not previously attended an interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia, while 18% stated that they had attended only 1 interdisciplinary team assessment for dementia.

Before the education, students rated their dementia ability as poor. Only 2% (1 of 54), of those with 0 to 1 assessment experience rated their ability for assessing dementia with an interdisciplinary team format as very good/excellent compared with 20% (9/46) of those previously attending ≥ 2 assessments (P = .03); other ratings of ability were not associated with prior experience.

There was a significant change in the students’ self-efficacy ratings pre- to postassessment (P < .05) (Table 2). Only 10% rated their ability to assess for dementia as very good/excellent in before the intervention compared with 96% in postassessment (P < .01). Students’ perception of the impact of behavioral problems on dementia care improved significantly (45% to 98%, P < .01). Similarly, student’s perception of their ability to assess behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and cognition improved significantly from 7 to 88%; 7 to 78%, and 18 to 92%, respectively (P < .01). Students perception of the role of social worker, neuropsychologist, geriatrician, and geriatric psychiatrist also improved significantly for most measures from 81 to 98% (P = .02), 87 to 98% (P = .05), 94 to 99% (P = .06), and 88 to 100% (P = .01), respectively.

The semistructured interviews revealed that awareness of behavioral problems associated with dementia varied for different behavioral problems. Although many students showed familiarity with depression, agitation, and psychosis, they were not comfortable assessing them in a patient with dementia. These students were less aware of other behavioral problems such as disinhibition, apathy, and movement disorders. Deficits were noted in the skill of administering commonly used global cognitive screens, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).15

In semistructured interviews, only 7% of senior medical students were comfortable assessing behavioral problems associated with dementia. Most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms. Similarly, only 7% of students were comfortable assessing caregiver burden, and most were not aware of any validated rating scale to assess caregiver burden. Only 1 in 5 students were comfortable using 2 cognitive screens to assess cognitive deficits. Many students stated that they were not routinely expected to perform common cognitive screens, such as the MMSE during their medical training except students who had expressed an interest in psychiatry and were expected to be proficient in the MMSE. Most students were making common mistakes, such as converting the 3-command task to 3 individual single commands, helping too much with serial 7s, and giving too much positive feedback throughout the test.

Discussion

Significant knowledge gaps regarding dementia were found in our study, which is in keeping with other studies in the area. Dementia knowledge deficits among medical trainees have been identified in the United Kingdom, Australia, and the US.6-9

In our study, a brief multicomponent experiential curriculum improved senior medical students’ perception and self-efficacy in diagnosing dementia. This is in keeping with other studies, such as the PAIRS Program.7 Findings from another study indicated that education for geriatric- oriented physicians should focus on experiential learning components through observation and interaction with older adults.16

A background of direct experience with older adults is associated with more positive attitudes toward older adults and increased interest in geriatric medicine.16 In our study, the exposure was brief; therefore, the results could not be compared with other long-term exposure studies. However, even with this brief intervention most students reported being comfortable with assessing caregiver burden (78%), behavioral problems of dementia (88%), and using ≥ 2 cognitive screens (92%). Comfortable in dementia assessment increased after the intervention from 10% to 96%. This finding is encouraging because brief multicomponent dementia education can be devised easily. This finding needs to be taken with caution because we did not conduct a formal skills evaluation.

A unique component of our experience was to learn medical students’ perception about the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on the trajectory, outcomes, and management of dementia. These symptoms included delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite and eating. Less than half the students thought that neuropsychiatric symptoms had a significant impact on dementia before the experience. Through didactics, systematic assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and interaction with caregivers, > 98% of students learned that these symptoms have a significant impact on dementia management.

This experience also emphasized the role of several disciplines in dementia assessment and management. Students’ experience positively influenced appreciation of the role of the memory clinic team. Our hope is that students will seek input from social workers, neuropsychologists, and other team members when working with patients with dementia or their caregivers. The common reason why primary care physicians focus on an exclusive medical model is the time commitment for communicating with an interdisciplinary team. Students experienced the feasibility of the interdisciplinary team involvement and how technology could be used for synchronous and asynchronous communication among team members. Medical students also were introduced to complex billing codes used when ≥ 3 disciplines assess/manage a geriatric patient.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of long-term follow-up evaluations, no metrics for practice changes clinical outcomes, and implementation in a single medical school. The postexperience evaluation in this study was performed immediately after the intervention. Long-term follow-up would inform whether the changes noted are durable. Because of the brief nature of our intervention, we do not believe that it would change practice in clinical care. It will be informative to follow this cohort of students to study whether their clinical approach to dementia care changes. The intervention needs to be replicated in other medical schools and in more heterogeneous groups to generalize the results of the study.

Conclusions

Senior medical students are not routinely exposed to interdisciplinary team assessments. Dementia knowledge gaps were prevalent in this cohort of senior medical students. Providing interdisciplinary geriatric educational experience improved their perception of their ability to assess for dementia and their recognition of the roles of interdisciplinary team members. Plans are in place to continue and expand the program to other complex geriatric syndromes.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Geriatrics Society. Oral presentation at the same meeting as part of the select Geriatric Education Methods and Materials Swap workshop.

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

2. Janca A, Aarli JA, Prilipko L, Dua T, Saxena S, Saraceno B. WHO/WFN survey of neurological services: a worldwide perspective. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247(1):29-34. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.03.003

3. Wilkins KM, Blazek MC, Brooks WB, Lehmann SW, Popeo D, Wagenaar D. Six things all medical students need to know about geriatric psychiatry (and how to teach them). Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):693-700. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0691-7

4. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461- 467. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh140

5. Lester PE, Dharmarajan TS, Weinstein E. The looming geriatrician shortage: ramifications and solutions. J Aging Health. 2019:898264319879325. doi:10.1177/0898264319879325

6. Struck BD, Bernard MA, Teasdale TA; Oklahoma University Geriatric Education G. Effect of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on third-year students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):2007-2011. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00473.x

7. Jefferson AL, Cantwell NG, Byerly LK, Morhardt D. Medical student education program in Alzheimer’s disease: the PAIRS Program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:80. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-80

8. Nagle BJ, Usita PM, Edland SD. United States medical students’ knowledge of Alzheimer disease. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:4. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.4

9. Scott TL, Kugelman M, Tulloch K. How medical professional students view older people with dementia: Implications for education and practice. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225329.

10. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649

11. McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377-383. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7

12. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Ger iatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

13. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, 3rd, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86

14. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

15. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

16. Fitzgerald JT, Wray LA, Halter JB, Williams BC, Supiano MA. Relating medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and experience to an interest in geriatric medicine. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):849-855. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.849

1. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2112-2117. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

2. Janca A, Aarli JA, Prilipko L, Dua T, Saxena S, Saraceno B. WHO/WFN survey of neurological services: a worldwide perspective. J Neurol Sci. 2006;247(1):29-34. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.03.003

3. Wilkins KM, Blazek MC, Brooks WB, Lehmann SW, Popeo D, Wagenaar D. Six things all medical students need to know about geriatric psychiatry (and how to teach them). Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):693-700. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0691-7

4. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Age Ageing. 2004;33(5):461- 467. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh140

5. Lester PE, Dharmarajan TS, Weinstein E. The looming geriatrician shortage: ramifications and solutions. J Aging Health. 2019:898264319879325. doi:10.1177/0898264319879325

6. Struck BD, Bernard MA, Teasdale TA; Oklahoma University Geriatric Education G. Effect of a mandatory geriatric medicine clerkship on third-year students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(11):2007-2011. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00473.x

7. Jefferson AL, Cantwell NG, Byerly LK, Morhardt D. Medical student education program in Alzheimer’s disease: the PAIRS Program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:80. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-80

8. Nagle BJ, Usita PM, Edland SD. United States medical students’ knowledge of Alzheimer disease. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:4. doi:10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.4

9. Scott TL, Kugelman M, Tulloch K. How medical professional students view older people with dementia: Implications for education and practice. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0225329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0225329.

10. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655. doi:10.1093/geront/20.6.649

11. McDowell I, Kristjansson B, Hill GB, Hebert R. Community screening for dementia: the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Modified Mini-Mental State Exam (3MS) compared. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):377-383. doi:10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00060-7

12. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Ger iatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

13. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH, 3rd, Morley JE. Comparison of the Saint Louis University mental status examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900-910. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86

14. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308

15. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

16. Fitzgerald JT, Wray LA, Halter JB, Williams BC, Supiano MA. Relating medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and experience to an interest in geriatric medicine. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):849-855. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.849

Highlights on Treatment of Progressive MS From ECTRIMS 2020

Promising phase 3 trial results from French researchers indicate that the first-in-class oral TKI masitinib may provide a new treatment option for patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) or nonactive secondary progressive MS (SPMS).

The masitinib study was noted by Dr Mark Freedman, professor of neurology at the University of Ottawa, as among the key findings on PPMS presented at ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS 2020. The French study reported that patients receiving masitinib over 96 weeks experienced significant delay in disability progression.

Dr Freedman explains how an analysis done by Mellon Center researchers may change how clinicians counsel patients about the risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) related to fingolimod treatment. Their research shows the incidence rate of PML among patients receiving fingolimod to be very low — in fact, fewer than 40 times that of patients receiving natalizumab.

Finally, Dr Freedman discuses an ad hoc analysis presented by leading MS researchers from University Hospital in Basel, Switzerland, which points to plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) levels as a prognostic biomarker of increased risk for worsening disability. Using data from the EXPAND trial, researchers found significant risk for increased disability among patients with nonactive SPMS who had elevated baseline GFAP.

Professor, Department of Neurology, University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; Director, Multiple Sclerosis Research Unit, The Ottawa Hospital – General Campus, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Mark S. Freedman, MSc, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) on the advisory board, board of directors, or other similar groups for: Actelion (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson); Alexion; Atara Biotherapeutics; BayerHealthcare; BiogenIdec; Celgene; Clene Nanomedicine; GRI Bio; Hoffman La-Roche; Magenta Therapeutics; Merck Serono; MedDay; Novartis; Sanofi-Genzyme; Teva Canada Innovation. Serve(d) as a member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi-Genzyme; EMD Serono. Received honoraria or consultation fees for: Actelion (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson); Alexion; BiogenIdec; Celgene (BMS); EMD Inc; Sanofi-Genzyme; Hoffman La-Roche; Merck Serono; Novartis; Teva Canada Innovation. Received research or educational grants from: Sanofi-Genzyme Canada; Hoffman-La Roche; EMD Inc.

Promising phase 3 trial results from French researchers indicate that the first-in-class oral TKI masitinib may provide a new treatment option for patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) or nonactive secondary progressive MS (SPMS).

The masitinib study was noted by Dr Mark Freedman, professor of neurology at the University of Ottawa, as among the key findings on PPMS presented at ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS 2020. The French study reported that patients receiving masitinib over 96 weeks experienced significant delay in disability progression.

Dr Freedman explains how an analysis done by Mellon Center researchers may change how clinicians counsel patients about the risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) related to fingolimod treatment. Their research shows the incidence rate of PML among patients receiving fingolimod to be very low — in fact, fewer than 40 times that of patients receiving natalizumab.

Finally, Dr Freedman discuses an ad hoc analysis presented by leading MS researchers from University Hospital in Basel, Switzerland, which points to plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) levels as a prognostic biomarker of increased risk for worsening disability. Using data from the EXPAND trial, researchers found significant risk for increased disability among patients with nonactive SPMS who had elevated baseline GFAP.

Professor, Department of Neurology, University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; Director, Multiple Sclerosis Research Unit, The Ottawa Hospital – General Campus, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Mark S. Freedman, MSc, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) on the advisory board, board of directors, or other similar groups for: Actelion (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson); Alexion; Atara Biotherapeutics; BayerHealthcare; BiogenIdec; Celgene; Clene Nanomedicine; GRI Bio; Hoffman La-Roche; Magenta Therapeutics; Merck Serono; MedDay; Novartis; Sanofi-Genzyme; Teva Canada Innovation. Serve(d) as a member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi-Genzyme; EMD Serono. Received honoraria or consultation fees for: Actelion (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson); Alexion; BiogenIdec; Celgene (BMS); EMD Inc; Sanofi-Genzyme; Hoffman La-Roche; Merck Serono; Novartis; Teva Canada Innovation. Received research or educational grants from: Sanofi-Genzyme Canada; Hoffman-La Roche; EMD Inc.

Promising phase 3 trial results from French researchers indicate that the first-in-class oral TKI masitinib may provide a new treatment option for patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) or nonactive secondary progressive MS (SPMS).

The masitinib study was noted by Dr Mark Freedman, professor of neurology at the University of Ottawa, as among the key findings on PPMS presented at ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS 2020. The French study reported that patients receiving masitinib over 96 weeks experienced significant delay in disability progression.

Dr Freedman explains how an analysis done by Mellon Center researchers may change how clinicians counsel patients about the risk for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) related to fingolimod treatment. Their research shows the incidence rate of PML among patients receiving fingolimod to be very low — in fact, fewer than 40 times that of patients receiving natalizumab.

Finally, Dr Freedman discuses an ad hoc analysis presented by leading MS researchers from University Hospital in Basel, Switzerland, which points to plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) levels as a prognostic biomarker of increased risk for worsening disability. Using data from the EXPAND trial, researchers found significant risk for increased disability among patients with nonactive SPMS who had elevated baseline GFAP.

Professor, Department of Neurology, University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; Director, Multiple Sclerosis Research Unit, The Ottawa Hospital – General Campus, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Mark S. Freedman, MSc, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) on the advisory board, board of directors, or other similar groups for: Actelion (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson); Alexion; Atara Biotherapeutics; BayerHealthcare; BiogenIdec; Celgene; Clene Nanomedicine; GRI Bio; Hoffman La-Roche; Magenta Therapeutics; Merck Serono; MedDay; Novartis; Sanofi-Genzyme; Teva Canada Innovation. Serve(d) as a member of a speakers bureau for: Sanofi-Genzyme; EMD Serono. Received honoraria or consultation fees for: Actelion (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson); Alexion; BiogenIdec; Celgene (BMS); EMD Inc; Sanofi-Genzyme; Hoffman La-Roche; Merck Serono; Novartis; Teva Canada Innovation. Received research or educational grants from: Sanofi-Genzyme Canada; Hoffman-La Roche; EMD Inc.

Survey explores mental health, services use in police officers

New research shows that about a quarter of police officers in one large force report past or present mental health problems.

Responding to a survey, 26% of police officers on the Dallas police department screened positive for depression, anxiety, PTSD, or symptoms of suicide ideation or self-harm.

Mental illness rates were particularly high among female officers, those who were divorced, widowed, or separated, and those with military experience.

The study also showed that concerns over confidentiality and stigma may prevent officers with mental illness from seeking treatment.

The results underscored the need to identify police officers with psychiatric problems and to connect them to the most appropriate individualized care, author Katelyn K. Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“This is a very hard-to-reach population, and because of that, we need to be innovative in reaching them for services,” she said.

The study was published online Oct. 7 in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are investigating various aspects of police officers’ well-being, including their nutritional needs and their occupational, physical, and mental health.

The current study included 434 members of the Dallas police department, the ninth largest in the United States. The mean age of the participants was 37 years, 82% were men, and about half were White. The 434 officers represented 97% of those invited to participate (n = 446) and 31% of the total patrol population of the Dallas police department (n = 1,413).

These officers completed a short survey on their smartphone that asked about lifetime diagnoses of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They were also asked whether they experienced suicidal ideation or self-harm during the previous 2 weeks.

Overall, 12% of survey respondents reported having been diagnosed with a mental illness. This, said Jetelina, is slightly lower than the rate reported in the general population.

Study participants who had not currently been diagnosed with a mental illness completed the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–2 (GAD-2), and the Primary Care–Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PC-PTSD).

Officers were considered to have a positive result if they had a score of 3 or more (PHQ-2, sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 92%; PC-PTSD-5, sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 85%; GAD-2, sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 83%).

About 26% of respondents had a positive screening for mental illness symptoms, mainly PTSD and depression, which Dr. Jetelina noted is a higher percentage than in the general population.

This rate of mental health symptoms is “high and concerning,” but not surprising because of the work of police officers, which could include attending to sometimes violent car crashes, domestic abuse situations, and armed conflicts, said Dr. Jetelina.

“They’re constantly exposed to traumatic calls for service; they see people on their worst day, 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. That stress and exposure will have a detrimental effect on mental health, and we have to pay more attention to that,” she said.

Dr. Jetelina pointed out that the surveys were completed in January and February 2020, before COVID-19 had become a cause of stress for everyone and before the increase in calls for defunding police amid a resurgence of Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

However, she stressed that racial biases and occupational stress among police officers are “nothing new for them.” For example, in 2016, five Dallas police officers were killed during Black Lives Matter protests because of their race/ethnicity.

More at risk

The study showed that certain subgroups of officers were more at risk for mental illness. After adjustment for confounders, including demographic characteristics, marital status, and educational level, the odds of being diagnosed with a mental illness during the course of one’s life were significantly higher among female officers than male officers (adjusted odds ratio, 3.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-8.68).

Officers who were divorced, widowed, or separated and those who had more experience and held a higher rank were also at greater risk for mental illness.

As well, (aOR, 3.25; 95% CI, 1.38-7.67).

The study also asked participants about use of mental health care services over the past 12 months. About 35% of those who had a current mental health diagnosis and 17% of those who screened positive for mental health symptoms reported using such services.

The study also asked those who screened positive about their interest in seeking such services. After adjustments, officers with suicidal ideation or self-harm were significantly more likely to be interested in getting help, compared with officers who did not report suicidal ideation or self-harm (aOR, 7.66; 95% CI, 1.70-34.48).

Dr. Jetelina was impressed that so many officers were keen to seek help, which “is a big positive,” she said. “It’s just a matter of better detecting who needs the help and better connecting them to medical services that meet their needs.”

Mindfulness exercise

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are conducting a pilot test of the use by police officers of smartwatches that monitor heart rate and oxygen levels. If measurements with these devices reach a predetermined threshold, the officers are “pinged” and are instructed to perform a mindfulness exercise in the field, she said.

Results so far “are really exciting,” said Dr. Jetelina. “Officers have found this extremely helpful and feasible, and so the next step is to test if this truly impacts mental illness over time.”

Routine mental health screening of officers might be beneficial, but only if it’s conducted in a manner “respectful of the officers’ needs and wants,” said Dr. Jetelina.

She pointed out that although psychological assessments are routinely carried out following an extreme traumatic call, such as one involving an officer-involved shooting, the “in-between” calls could have a more severe cumulative impact on mental health.

It’s important to provide officers with easy-to-access services tailored for their individual needs, said Dr. Jetelina.

‘Numb to it’

Eighteen patrol officers also participated in a focus group, during which several themes regarding the use of mental health care services emerged. One theme was the inability of officers to identify when they’re personally experiencing a mental health problem.

Participants said they had become “numb” to the traumatic events on the job, which is “concerning,” Dr. Jetelina said. “They think that having nightmares every week is completely normal, but it’s not, and this needs to be addressed.”

Other themes that emerged from focus groups included the belief that psychologists can’t relate to police stressors; concerns about confidentiality (one sentiment that was expressed was “you’re an idiot” if you “trust this department”); and stigma for officers who seek mental health care (participants talked about “reprisal” from seeing “a shrink,” including being labeled as “a nutter” and losing their job).

Dr. Jetelina noted that some “champion” officers revealed their mental health journey during focus groups, which tended to “open a Pandora’s box” for others to discuss their experience. She said these champions could be leveraged throughout the police department to help reduce stigma.

The study included participants from only one police department, although rigorous data collection allows for generalizability to the entire patrol department, say the authors. Although the study included only brief screens of mental illness symptoms, these short versions of screening tests have high sensitivity and specificity for mental illness in primary care, they noted.

The next step for the researchers is to study how mental illness and symptoms affect job performance, said Dr. Jetelina. “Does this impact excessive use of force? Does this impact workers’ compensation? Does this impact dispatch times, the time it takes for a police officer to respond to [a] 911 call?”

Possible underrepresentation

Anthony T. Ng, MD, regional medical director, East Region Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network in Mansfield, Conn., and member of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Communications, found the study “helpful.”

However, the 26% who tested positive for mental illness may be an “underrepresentation” of the true picture, inasmuch as police officers might minimize or be less than truthful about their mental health status, said Dr. Ng.

Law enforcement has “never been easy,” but stressors may have escalated recently as police forces deal with shortages of staff and jails, said Dr. Ng.

He also noted that officers might face stressors at home. “Evidence shows that domestic violence is quite high – or higher than average – among law enforcement,” he said. “All these things add up.”

Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals should be “aware of the unique challenges” that police officers face and be “proactively involved” in providing guidance and education on mitigating stress, said Dr. Ng.

“You have police officers wearing body armor, so why can’t you give them some training to learn how to have psychiatric or psychological body armor?” he said. But it’s a two-way street; police forces should be open to outreach from mental health professionals. “We have to meet halfway.”

Compassion fatigue

In an accompanying commentary, John M. Violanti, PhD, of the department of epidemiology and environmental health at the State University of New York at Buffalo, said the article helps bring “to the forefront” the issue of the psychological dangers of police work.

There is conjecture as to why police experience mental distress, said Dr. Violanti, who pointed to a study of New York City police suicides during the 1930s that suggested that police have a “social license” for aggressive behavior but are restrained as part of public trust, placing them in a position of “psychological strain.”

“This situation may be reflective of the same situation police find themselves today,” said Dr. Violanti.

“Compassion fatigue,” a feeling of mental exhaustion caused by the inability to care for all persons in trouble, may also be a factor, as could the constant stress that leaves police officers feeling “cynical and isolated from others,” he wrote.

“The socialization process of becoming a police officer is associated with constrictive reasoning, viewing the world as either right or wrong, which leaves no middle ground for alternatives to deal with mental distress,” Dr. Violanti said.

He noted that police officers may abuse alcohol because of stress, peer pressure, isolation, and a culture that approves of alcohol use. “Officers tend to drink together and reinforce their own values.”.