User login

Dual antiplatelet Tx for stroke prevention: Worth the risk?

The incidence of ischemic stroke in the United States is estimated to be more than 795,000 events each year.1 After an initial stroke, the rate of recurrence is 5% to 20% within the first year, with the greatest prevalence in the first 90 days following an event.2-5 Although dual antiplatelet therapy, often with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor such as clopidogrel, reduces the risk for recurrent cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular events, and death following acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous intervention, the role of combination antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke continues to be debated.6 Reconciling currently available data can be challenging, as many studies vary considerably in both the time to antiplatelet initiation and duration of therapy.

For many years, aspirin alone was the drug of choice for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke.7 Efficacy is similar at dosages anywhere between 50 and 1500 mg/d; higher doses incur a greater risk for gastrointestinal hemorrhage.7 Current secondary prevention guidelines recommend a dosage of aspirin somewhere between 50 and 325 mg/d.7

Alternative agents have also been evaluated for secondary stroke prevention, but only clopidogrel is currently considered an acceptable alternative for monotherapy based on a subgroup analysis of the CAPRIE (Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events) trial.7,8 Other alternatives, including cilostazol, ticlopidine, and ticagrelor, are limited by a lack of data, adverse drug reactions, or unproven efficacy and are not recommended in current guidelines.7,9 The ongoing THALES (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack Treated with Ticagrelor and Aspirin for Prevention of Stroke and Death) trial, assessing combination ticagrelor and aspirin, may identify an additional option for antiplatelet therapy following acute stroke.10

The current guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) support the combination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole (ASA-ERDP) as a long-term alternative to aspirin monotherapy.7,11 Additionally, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin (CLO-ASA) is now recommended for limited duration in the early management of ischemic stroke.11

This review will explore the role of dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), with particular focus on acute use of CLO-ASA.

Clopidogrel and aspirin: When to initiate, when to stop

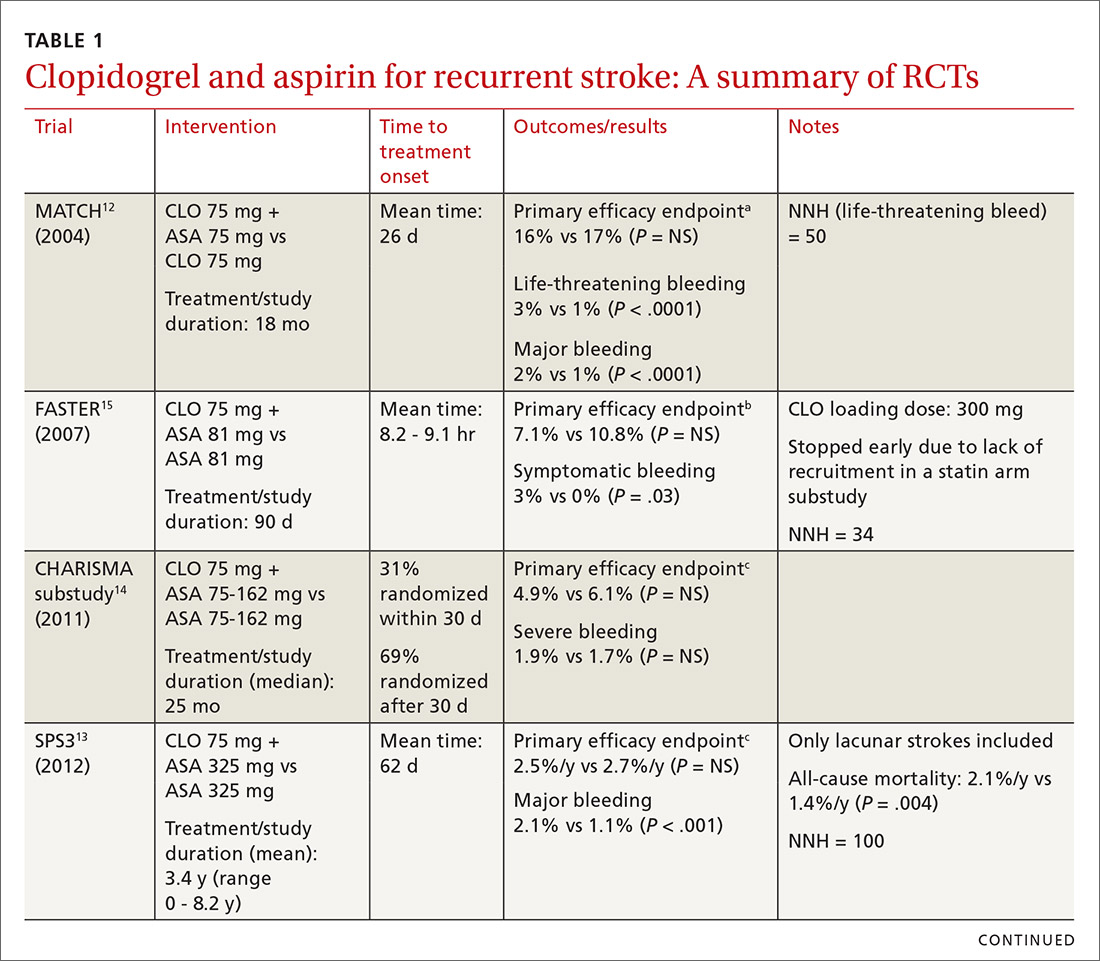

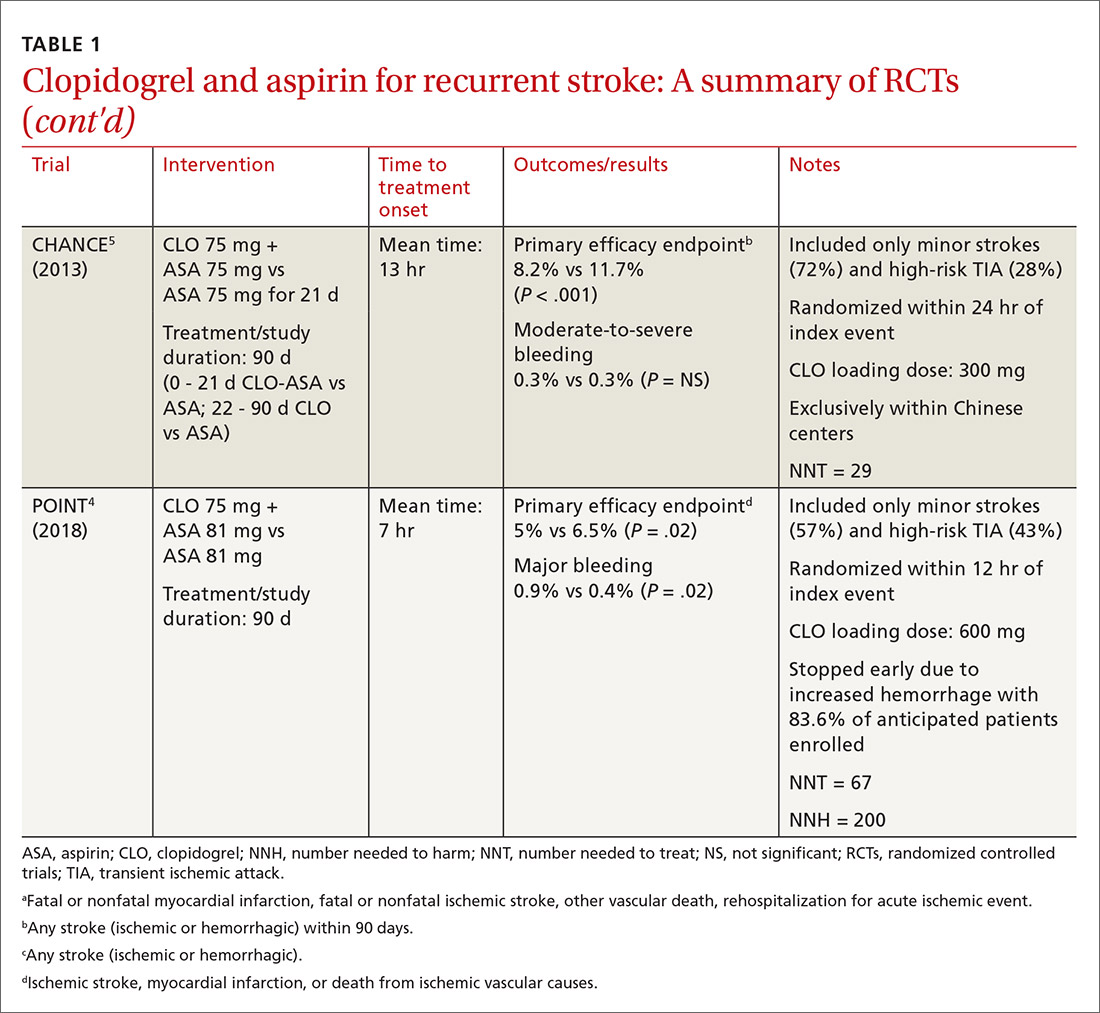

The combined use of clopidogrel and aspirin has been well-studied for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and TIA. However, interpreting and applying the results of these trials can be challenging given key differences in both time to treatment initiation and the duration of combination therapy. Highlights of the major randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the safety and efficacy of CLO-ASA are detailed in TABLE 1.4,5,12-15

Initial trials evaluating CLO-ASA for secondary stroke prevention, including the MATCH (Management of ATherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-risk patients),12 SPS3 (Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes),13 and CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischaemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance)14 trials assessed the long-term benefits of combination therapy, with most patients initiating treatment a month or more following an initial stroke and continuing therapy for at least 18 months.12-14 Results from these trials indicate that long-term use (> 18 months) of CLO-ASA does not reduce recurrent events but increases rates of clinically significant bleeding.12-14

Continue to: A look at Tx timing

A look at Tx timing. Since these initial attempts failed to show a long-term benefit with CLO-ASA, subsequent trials attempted to establish an appropriate balance between the optimal time to initiate CLO-ASA and the optimal duration of therapy. The FASTER (Fast Assessment of Stroke and Transient ischaemic attack to prevent Early Recurrence) trial was a small pilot study of 392 patients randomized to CLO-ASA or aspirin within 24 hours of stroke or TIA onset and continued for only 3 months.15 While this trial did not find a significant reduction in ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke with combination therapy, there was a large numerical difference in event rates between the 2 groups (7.1% CLO-ASA vs 10.8% aspirin).15 An underpowered sample size (due to difficulty recruiting participants) is likely responsible for the lack of statistical significance.15 Despite the trial’s failure to show a benefit with acute use of CLO-ASA, it suggested a possible benefit that led to further investigation in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-risk patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events)5 and POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) 4 trials.

The CHANCE trial conducted in China included more than 5000 patients with acute minor ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 [a scale that assesses the risk of stroke on the basis of age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, and presence or absence of diabetes] score ≥ 4).5 Similar to FASTER, patients were randomized within 24 hours of symptom onset to CLO-ASA or aspirin. However, CHANCE utilized combination therapy for only 21 days, after which the patients were continued on clopidogrel monotherapy for up to 90 days; the aspirin monotherapy group continued aspirin for 90 days.

After 90 days, patients initially using combination therapy had significantly lower rates of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke vs those assigned to aspirin monotherapy. This result was driven heavily by the reduction in ischemic stroke (7.9% CLO-ASA vs 11.4% aspirin; P < .001). Additionally, there was no significant difference in moderate or severe bleeding events between the 2 groups.5 Efficacy and safety results were similar among a subgroup of patients who were randomized to treatment within 12 hours rather than 24 hours from symptom onset.16 The CHANCE trial was the first major study to demonstrate a clinical benefit of CLO-ASA to prevent recurrent stroke. Accordingly, the 2018 AHA/ASA guidelines included a new recommendation regarding secondary prevention for the use of CLO-ASA initiated within 24 hours and continued for 21 days following a minor stroke or TIA.11

A drawback of the CHANCE trial was its narrow patient population of only Chinese patients, which may limit applicability in clinical practice. There are known genetic variations in cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) that may affect clopidogrel metabolism. CYP2C19 is responsible for the conversion of clopidogrel into its activated form in vivo. Carriers of a CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele may have reduced clopidogrel activation and subsequent reduced antiplatelet activity. Such loss-of-function alleles are more common in Asian populations vs non-Asian populations.17

A substudy of CHANCE found that CLO-ASA’s efficacy benefit was preserved in noncarrier patients; however, patients with the CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele did not benefit from combination therapy.18 Interestingly, these genetic differences did not affect bleeding outcomes. Given that approximately 60% of patients in the CHANCE substudy were loss-of-function allele carriers and that the overall study results still showed benefit with combination therapy, application of CHANCE’s findings to broader populations may not be a concern after all.18

Continue to: In efforts to gain insight...

In efforts to gain insight on CLO-ASA’s use in a more diverse patient population, the POINT trial included almost 5000 patients, with 82% from the United States, who were randomized within 12 hours of symptom onset to CLO-ASA or aspirin monotherapy for 90 days.4 Similar to the CHANCE study, the POINT study included patients with mild ischemic strokes (NIHSS ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 ≥ 4). Combination therapy significantly reduced the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or death from an ischemic event. Contrary to CHANCE, there was a significant increase in major bleeding in those assigned to combination therapy, which resulted in the trial being stopped early.4

A closer look at safety differences. CHANCE and POINT were the first major trials to show a benefit of CLO-ASA for secondary prevention of stroke, yet their differences in safety outcomes, specifically major hemorrhage, argued for a deeper reconciliation of their results.4,5 While both trials initiated secondary prevention within 24 hours of symptom onset, the difference in duration of combination therapy (21 days in CHANCE vs 90 days in POINT) likely impacted the rates of hemorrhage. When results from POINT were stratified by time period, particularly within the first 30 days of therapy (similar to the 21-day treatment duration of CHANCE), combination therapy significantly reduced the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke, MI, or death from an ischemic event (3.9% CLO-ASA vs 5.8% aspirin; P = .02) without an increased risk for major hemorrhage. Between 30 and 90 days, this efficacy benefit disappeared. However, bleeding rates between groups continued to separate throughout the 90-day course. In this light, the 30-day outcomes of POINT are largely similar to CHANCE and support the short-term use of CLO-ASA for secondary prevention without an associated increase in major bleeding.4,5

Antiplatelet dosing in POINT and CHANCE may also play a role in the contrasting safety results between the trials.4,5 While both studies utilized clopidogrel loading doses, POINT used 600 mg while CHANCE used 300 mg. Clopidogrel maintenance dosing was the same at 75 mg/d. In CHANCE, aspirin dosing was protocolized to 75 mg/d; however, in POINT, 31% of patients used > 100 mg/d aspirin.4,5 It is possible that the higher doses of both aspirin and clopidogrel in the POINT trial contributed to the difference in the occurrence of major hemorrhage between the treatment groups in these trials.

The takeaway. Based on currently available data, patients who are best suited to benefit from CLO-ASA are those who have had minor noncardioembolic ischemic strokes or high-risk TIAs.4,5,11 Clopidogrel should be given as a 300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d given concomitantly with aspirin at a dose no higher than 100 mg/d. CLO-ASA therapy should be initiated within 24 hours of symptom onset and be continued for no longer than 1 month, after which chronic preventive therapy with either aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy should be started.4,5,11

Dipyridamole and aspirin: A controversial option

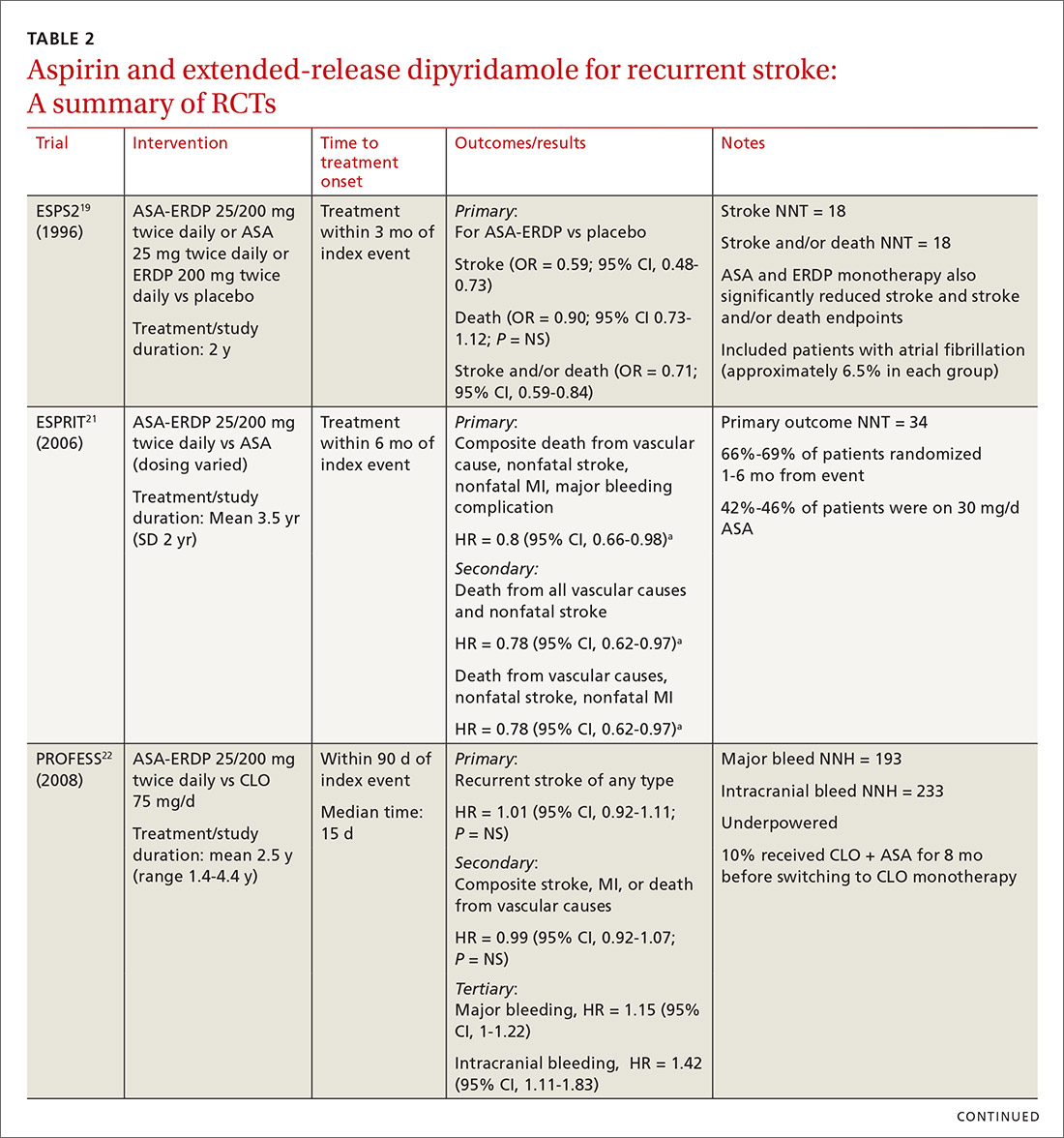

Since the approval of the combination product ASA-ERDP, there has been considerable controversy about using this combination over other therapies, such as aspirin or clopidogrel, for recurrent ischemic stroke prevention. Much of this controversy arises from limitations in the trial designs.

Continue to: The first trial to show benefit...

The first trial to show benefit with ASA-ERDP was ESPS2 (European Stroke Prevention Study 2), which demonstrated superiority of the combination over placebo in reducing recurrent stroke when treatment was added within 3 months of an index stroke.19 A few studies have evaluated ASA-ERDP compared to aspirin monotherapy; however, most of these studies were small and did not show any difference in outcomes.20 Only ESPRIT (European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischaemia Trial)21 carried significant weight in a 2013 meta-analysis, which showed a significant reduction in recurrent events with the combination product compared to aspirin monotherapy.20

Both the ESPS2 and ESPRIT trials had significant limitations.19,21 Patients in both studies had vascular comorbidities including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD); however, pharmacotherapies designated to treat these diseases were not mentioned in the demographic data, nor were these medications taken into consideration to limit potential bias.19,21 Retrospectively, a significant proportion of aspirin doses utilized as a control in ESPRIT were inferior to the guideline-recommended dosing with 42% to 46% of patients receiving 30 mg/d.21 Despite these controversies, ASA-ERDP is still considered an alternative to aspirin monotherapy in the guidelines.7

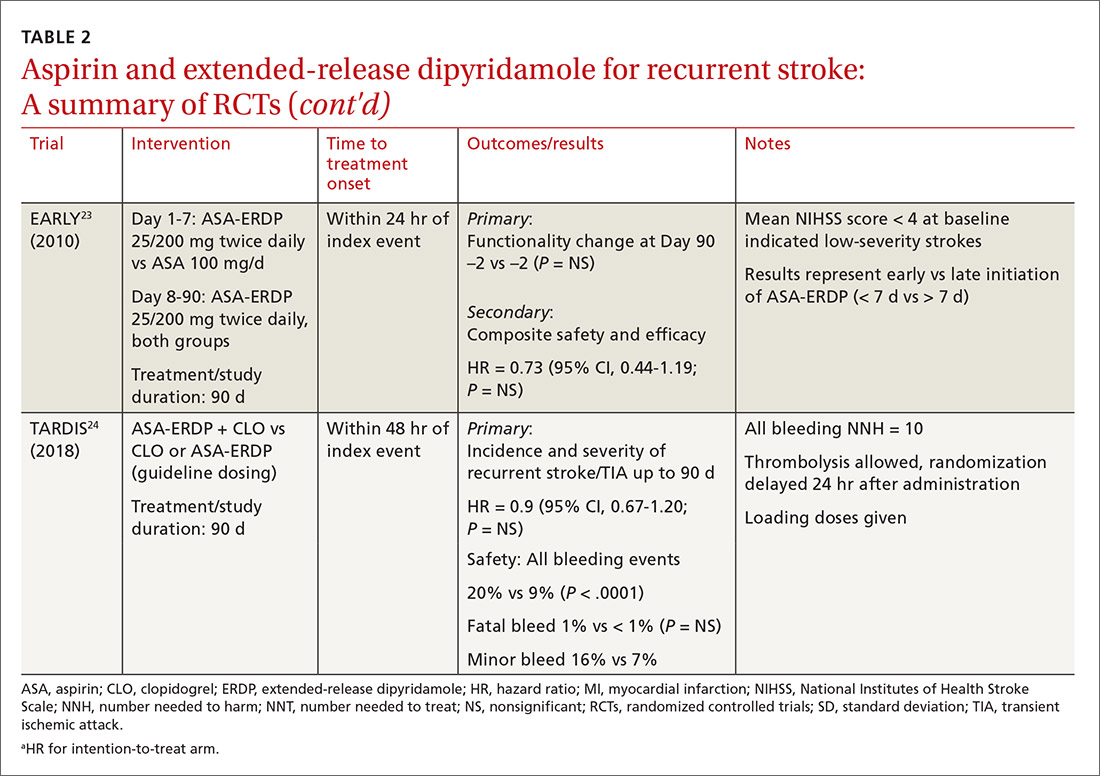

The timing of ASA-ERDP initiation appears to be inversely related to the efficacy of the combination over therapeutic alternatives. Studies in which the therapy was initiated 3 to 6 months from the index stroke indicated favorable outcomes for the combination when compared to ASA or ERDP monotherapy.19,21 Studies utilizing early initiation (ie, within 24 or 48 hours of the index event) or even within 3 weeks showed no difference in outcomes; however, this may be due in part to the use of clopidogrel or other combination antiplatelet therapy as active comparators.22-24

Early initiation of ASA-ERDP also demonstrated a higher risk of major and intracranial bleeding compared to clopidogrel.22 Additionally, use of triple therapy with ASA-ERDP plus clopidogrel increased bleeding events without improving efficacy.24 More recent studies of ASA-ERDP are focusing on earlier initiation of therapy; it is unknown whether the benefits of late initiation will be confirmed in future studies. Highlights of the major RCTs evaluating the safety and efficacy of ASA-ERDP are detailed in TABLE 219,21-24.

The takeaway. Methodological issues and potential confounding factors in many of the key trials for ASA-ERDP make it challenging to fully discern the role that ASA-ERDP may play in the secondary prevention of stroke. Further evidence utilizing appropriate controls, timing, and assessment of confounders is needed. Additionally, ASA-ERDP is plagued by tolerability issues such as headache, nausea, and vomiting, leading to higher rates of discontinuation than its comparators in clinical trials. Accordingly, the maintenance use of ASA-ERDP for secondary stroke prevention may be considered less preferred than other recommended alternatives such as aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapies.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert S. Helmer, PharmD, BCPS, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, 650 Clinic Drive, Suite 2100, Mobile, AL 36688; Rsh0011@auburn.edu.

1. CDC. Stroke Facts. Last updated January 31, 2020. www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

2. Amarenco P, Lavallee PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542.

3. Amarenco P, Lavallee PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2182-2190.

4. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215-225.

5. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11-19.

6. Bowry AD, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel plus aspirin as compared to antiplatelet monotherapy for the prevention of vascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:960-966.

7. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160-2236.

8. Gent M, Beaumont D, Blanchard J, et al. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet. 1996;348:1329-1339.

9. Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e601S-e636S.

10. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, et al. The acute stroke or transient ischemic attack treated with ticagrelor and aspirin for prevention of stroke and death (THALES) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2019;14:745‐751.

11. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110.

12. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331-337.

13. Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, et al. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:817-825.

14. Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Easton JD, et al. Effect of clopidogrel plus ASA vs. ASA early after TIA and ischaemic stroke: a substudy of the CHARISMA trial. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:3-9.

15. Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, et al. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961-969.

16. Li Z, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Treatment effect of clopidogrel plus aspirin within 12 hours of acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003038.

17. Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:317-323.

18. Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, et al. Association between CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele status and efficacy of clopidogrel for risk reduction among patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA. 2016;316:70-78.

19. Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, et al. European Stroke Prevention Study 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143:1-13.

20. Li X, Zhou G, Zhou X, et al. The efficacy and safety of aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin in secondary prevention following TIA or stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:92-96.

21. Halkes PH, van Gijn J, Kapelle IJ, et al. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1665-1673.

22. Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1238-1251.

23. Dengler R, Diener HC, Schwartz A, et al. Early treatment with aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole for transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke within 24 h of symptom onset (EARLY trial): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:159-166.

24. Bath PM, Woodhouse LJ, Appleton JP, et al. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole versus clopidogrel alone or aspirin and dipyridamole in patients with acute cerebral ischaemia (TARDIS): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:850-859.

The incidence of ischemic stroke in the United States is estimated to be more than 795,000 events each year.1 After an initial stroke, the rate of recurrence is 5% to 20% within the first year, with the greatest prevalence in the first 90 days following an event.2-5 Although dual antiplatelet therapy, often with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor such as clopidogrel, reduces the risk for recurrent cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular events, and death following acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous intervention, the role of combination antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke continues to be debated.6 Reconciling currently available data can be challenging, as many studies vary considerably in both the time to antiplatelet initiation and duration of therapy.

For many years, aspirin alone was the drug of choice for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke.7 Efficacy is similar at dosages anywhere between 50 and 1500 mg/d; higher doses incur a greater risk for gastrointestinal hemorrhage.7 Current secondary prevention guidelines recommend a dosage of aspirin somewhere between 50 and 325 mg/d.7

Alternative agents have also been evaluated for secondary stroke prevention, but only clopidogrel is currently considered an acceptable alternative for monotherapy based on a subgroup analysis of the CAPRIE (Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events) trial.7,8 Other alternatives, including cilostazol, ticlopidine, and ticagrelor, are limited by a lack of data, adverse drug reactions, or unproven efficacy and are not recommended in current guidelines.7,9 The ongoing THALES (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack Treated with Ticagrelor and Aspirin for Prevention of Stroke and Death) trial, assessing combination ticagrelor and aspirin, may identify an additional option for antiplatelet therapy following acute stroke.10

The current guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) support the combination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole (ASA-ERDP) as a long-term alternative to aspirin monotherapy.7,11 Additionally, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin (CLO-ASA) is now recommended for limited duration in the early management of ischemic stroke.11

This review will explore the role of dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), with particular focus on acute use of CLO-ASA.

Clopidogrel and aspirin: When to initiate, when to stop

The combined use of clopidogrel and aspirin has been well-studied for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and TIA. However, interpreting and applying the results of these trials can be challenging given key differences in both time to treatment initiation and the duration of combination therapy. Highlights of the major randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the safety and efficacy of CLO-ASA are detailed in TABLE 1.4,5,12-15

Initial trials evaluating CLO-ASA for secondary stroke prevention, including the MATCH (Management of ATherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-risk patients),12 SPS3 (Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes),13 and CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischaemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance)14 trials assessed the long-term benefits of combination therapy, with most patients initiating treatment a month or more following an initial stroke and continuing therapy for at least 18 months.12-14 Results from these trials indicate that long-term use (> 18 months) of CLO-ASA does not reduce recurrent events but increases rates of clinically significant bleeding.12-14

Continue to: A look at Tx timing

A look at Tx timing. Since these initial attempts failed to show a long-term benefit with CLO-ASA, subsequent trials attempted to establish an appropriate balance between the optimal time to initiate CLO-ASA and the optimal duration of therapy. The FASTER (Fast Assessment of Stroke and Transient ischaemic attack to prevent Early Recurrence) trial was a small pilot study of 392 patients randomized to CLO-ASA or aspirin within 24 hours of stroke or TIA onset and continued for only 3 months.15 While this trial did not find a significant reduction in ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke with combination therapy, there was a large numerical difference in event rates between the 2 groups (7.1% CLO-ASA vs 10.8% aspirin).15 An underpowered sample size (due to difficulty recruiting participants) is likely responsible for the lack of statistical significance.15 Despite the trial’s failure to show a benefit with acute use of CLO-ASA, it suggested a possible benefit that led to further investigation in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-risk patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events)5 and POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) 4 trials.

The CHANCE trial conducted in China included more than 5000 patients with acute minor ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 [a scale that assesses the risk of stroke on the basis of age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, and presence or absence of diabetes] score ≥ 4).5 Similar to FASTER, patients were randomized within 24 hours of symptom onset to CLO-ASA or aspirin. However, CHANCE utilized combination therapy for only 21 days, after which the patients were continued on clopidogrel monotherapy for up to 90 days; the aspirin monotherapy group continued aspirin for 90 days.

After 90 days, patients initially using combination therapy had significantly lower rates of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke vs those assigned to aspirin monotherapy. This result was driven heavily by the reduction in ischemic stroke (7.9% CLO-ASA vs 11.4% aspirin; P < .001). Additionally, there was no significant difference in moderate or severe bleeding events between the 2 groups.5 Efficacy and safety results were similar among a subgroup of patients who were randomized to treatment within 12 hours rather than 24 hours from symptom onset.16 The CHANCE trial was the first major study to demonstrate a clinical benefit of CLO-ASA to prevent recurrent stroke. Accordingly, the 2018 AHA/ASA guidelines included a new recommendation regarding secondary prevention for the use of CLO-ASA initiated within 24 hours and continued for 21 days following a minor stroke or TIA.11

A drawback of the CHANCE trial was its narrow patient population of only Chinese patients, which may limit applicability in clinical practice. There are known genetic variations in cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) that may affect clopidogrel metabolism. CYP2C19 is responsible for the conversion of clopidogrel into its activated form in vivo. Carriers of a CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele may have reduced clopidogrel activation and subsequent reduced antiplatelet activity. Such loss-of-function alleles are more common in Asian populations vs non-Asian populations.17

A substudy of CHANCE found that CLO-ASA’s efficacy benefit was preserved in noncarrier patients; however, patients with the CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele did not benefit from combination therapy.18 Interestingly, these genetic differences did not affect bleeding outcomes. Given that approximately 60% of patients in the CHANCE substudy were loss-of-function allele carriers and that the overall study results still showed benefit with combination therapy, application of CHANCE’s findings to broader populations may not be a concern after all.18

Continue to: In efforts to gain insight...

In efforts to gain insight on CLO-ASA’s use in a more diverse patient population, the POINT trial included almost 5000 patients, with 82% from the United States, who were randomized within 12 hours of symptom onset to CLO-ASA or aspirin monotherapy for 90 days.4 Similar to the CHANCE study, the POINT study included patients with mild ischemic strokes (NIHSS ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 ≥ 4). Combination therapy significantly reduced the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or death from an ischemic event. Contrary to CHANCE, there was a significant increase in major bleeding in those assigned to combination therapy, which resulted in the trial being stopped early.4

A closer look at safety differences. CHANCE and POINT were the first major trials to show a benefit of CLO-ASA for secondary prevention of stroke, yet their differences in safety outcomes, specifically major hemorrhage, argued for a deeper reconciliation of their results.4,5 While both trials initiated secondary prevention within 24 hours of symptom onset, the difference in duration of combination therapy (21 days in CHANCE vs 90 days in POINT) likely impacted the rates of hemorrhage. When results from POINT were stratified by time period, particularly within the first 30 days of therapy (similar to the 21-day treatment duration of CHANCE), combination therapy significantly reduced the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke, MI, or death from an ischemic event (3.9% CLO-ASA vs 5.8% aspirin; P = .02) without an increased risk for major hemorrhage. Between 30 and 90 days, this efficacy benefit disappeared. However, bleeding rates between groups continued to separate throughout the 90-day course. In this light, the 30-day outcomes of POINT are largely similar to CHANCE and support the short-term use of CLO-ASA for secondary prevention without an associated increase in major bleeding.4,5

Antiplatelet dosing in POINT and CHANCE may also play a role in the contrasting safety results between the trials.4,5 While both studies utilized clopidogrel loading doses, POINT used 600 mg while CHANCE used 300 mg. Clopidogrel maintenance dosing was the same at 75 mg/d. In CHANCE, aspirin dosing was protocolized to 75 mg/d; however, in POINT, 31% of patients used > 100 mg/d aspirin.4,5 It is possible that the higher doses of both aspirin and clopidogrel in the POINT trial contributed to the difference in the occurrence of major hemorrhage between the treatment groups in these trials.

The takeaway. Based on currently available data, patients who are best suited to benefit from CLO-ASA are those who have had minor noncardioembolic ischemic strokes or high-risk TIAs.4,5,11 Clopidogrel should be given as a 300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d given concomitantly with aspirin at a dose no higher than 100 mg/d. CLO-ASA therapy should be initiated within 24 hours of symptom onset and be continued for no longer than 1 month, after which chronic preventive therapy with either aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy should be started.4,5,11

Dipyridamole and aspirin: A controversial option

Since the approval of the combination product ASA-ERDP, there has been considerable controversy about using this combination over other therapies, such as aspirin or clopidogrel, for recurrent ischemic stroke prevention. Much of this controversy arises from limitations in the trial designs.

Continue to: The first trial to show benefit...

The first trial to show benefit with ASA-ERDP was ESPS2 (European Stroke Prevention Study 2), which demonstrated superiority of the combination over placebo in reducing recurrent stroke when treatment was added within 3 months of an index stroke.19 A few studies have evaluated ASA-ERDP compared to aspirin monotherapy; however, most of these studies were small and did not show any difference in outcomes.20 Only ESPRIT (European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischaemia Trial)21 carried significant weight in a 2013 meta-analysis, which showed a significant reduction in recurrent events with the combination product compared to aspirin monotherapy.20

Both the ESPS2 and ESPRIT trials had significant limitations.19,21 Patients in both studies had vascular comorbidities including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD); however, pharmacotherapies designated to treat these diseases were not mentioned in the demographic data, nor were these medications taken into consideration to limit potential bias.19,21 Retrospectively, a significant proportion of aspirin doses utilized as a control in ESPRIT were inferior to the guideline-recommended dosing with 42% to 46% of patients receiving 30 mg/d.21 Despite these controversies, ASA-ERDP is still considered an alternative to aspirin monotherapy in the guidelines.7

The timing of ASA-ERDP initiation appears to be inversely related to the efficacy of the combination over therapeutic alternatives. Studies in which the therapy was initiated 3 to 6 months from the index stroke indicated favorable outcomes for the combination when compared to ASA or ERDP monotherapy.19,21 Studies utilizing early initiation (ie, within 24 or 48 hours of the index event) or even within 3 weeks showed no difference in outcomes; however, this may be due in part to the use of clopidogrel or other combination antiplatelet therapy as active comparators.22-24

Early initiation of ASA-ERDP also demonstrated a higher risk of major and intracranial bleeding compared to clopidogrel.22 Additionally, use of triple therapy with ASA-ERDP plus clopidogrel increased bleeding events without improving efficacy.24 More recent studies of ASA-ERDP are focusing on earlier initiation of therapy; it is unknown whether the benefits of late initiation will be confirmed in future studies. Highlights of the major RCTs evaluating the safety and efficacy of ASA-ERDP are detailed in TABLE 219,21-24.

The takeaway. Methodological issues and potential confounding factors in many of the key trials for ASA-ERDP make it challenging to fully discern the role that ASA-ERDP may play in the secondary prevention of stroke. Further evidence utilizing appropriate controls, timing, and assessment of confounders is needed. Additionally, ASA-ERDP is plagued by tolerability issues such as headache, nausea, and vomiting, leading to higher rates of discontinuation than its comparators in clinical trials. Accordingly, the maintenance use of ASA-ERDP for secondary stroke prevention may be considered less preferred than other recommended alternatives such as aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapies.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert S. Helmer, PharmD, BCPS, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, 650 Clinic Drive, Suite 2100, Mobile, AL 36688; Rsh0011@auburn.edu.

The incidence of ischemic stroke in the United States is estimated to be more than 795,000 events each year.1 After an initial stroke, the rate of recurrence is 5% to 20% within the first year, with the greatest prevalence in the first 90 days following an event.2-5 Although dual antiplatelet therapy, often with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor such as clopidogrel, reduces the risk for recurrent cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular events, and death following acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous intervention, the role of combination antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke continues to be debated.6 Reconciling currently available data can be challenging, as many studies vary considerably in both the time to antiplatelet initiation and duration of therapy.

For many years, aspirin alone was the drug of choice for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke.7 Efficacy is similar at dosages anywhere between 50 and 1500 mg/d; higher doses incur a greater risk for gastrointestinal hemorrhage.7 Current secondary prevention guidelines recommend a dosage of aspirin somewhere between 50 and 325 mg/d.7

Alternative agents have also been evaluated for secondary stroke prevention, but only clopidogrel is currently considered an acceptable alternative for monotherapy based on a subgroup analysis of the CAPRIE (Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events) trial.7,8 Other alternatives, including cilostazol, ticlopidine, and ticagrelor, are limited by a lack of data, adverse drug reactions, or unproven efficacy and are not recommended in current guidelines.7,9 The ongoing THALES (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack Treated with Ticagrelor and Aspirin for Prevention of Stroke and Death) trial, assessing combination ticagrelor and aspirin, may identify an additional option for antiplatelet therapy following acute stroke.10

The current guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) support the combination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole (ASA-ERDP) as a long-term alternative to aspirin monotherapy.7,11 Additionally, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin (CLO-ASA) is now recommended for limited duration in the early management of ischemic stroke.11

This review will explore the role of dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), with particular focus on acute use of CLO-ASA.

Clopidogrel and aspirin: When to initiate, when to stop

The combined use of clopidogrel and aspirin has been well-studied for secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and TIA. However, interpreting and applying the results of these trials can be challenging given key differences in both time to treatment initiation and the duration of combination therapy. Highlights of the major randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the safety and efficacy of CLO-ASA are detailed in TABLE 1.4,5,12-15

Initial trials evaluating CLO-ASA for secondary stroke prevention, including the MATCH (Management of ATherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High-risk patients),12 SPS3 (Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes),13 and CHARISMA (Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischaemic Stabilization, Management and Avoidance)14 trials assessed the long-term benefits of combination therapy, with most patients initiating treatment a month or more following an initial stroke and continuing therapy for at least 18 months.12-14 Results from these trials indicate that long-term use (> 18 months) of CLO-ASA does not reduce recurrent events but increases rates of clinically significant bleeding.12-14

Continue to: A look at Tx timing

A look at Tx timing. Since these initial attempts failed to show a long-term benefit with CLO-ASA, subsequent trials attempted to establish an appropriate balance between the optimal time to initiate CLO-ASA and the optimal duration of therapy. The FASTER (Fast Assessment of Stroke and Transient ischaemic attack to prevent Early Recurrence) trial was a small pilot study of 392 patients randomized to CLO-ASA or aspirin within 24 hours of stroke or TIA onset and continued for only 3 months.15 While this trial did not find a significant reduction in ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke with combination therapy, there was a large numerical difference in event rates between the 2 groups (7.1% CLO-ASA vs 10.8% aspirin).15 An underpowered sample size (due to difficulty recruiting participants) is likely responsible for the lack of statistical significance.15 Despite the trial’s failure to show a benefit with acute use of CLO-ASA, it suggested a possible benefit that led to further investigation in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-risk patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events)5 and POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) 4 trials.

The CHANCE trial conducted in China included more than 5000 patients with acute minor ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 [a scale that assesses the risk of stroke on the basis of age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, and presence or absence of diabetes] score ≥ 4).5 Similar to FASTER, patients were randomized within 24 hours of symptom onset to CLO-ASA or aspirin. However, CHANCE utilized combination therapy for only 21 days, after which the patients were continued on clopidogrel monotherapy for up to 90 days; the aspirin monotherapy group continued aspirin for 90 days.

After 90 days, patients initially using combination therapy had significantly lower rates of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke vs those assigned to aspirin monotherapy. This result was driven heavily by the reduction in ischemic stroke (7.9% CLO-ASA vs 11.4% aspirin; P < .001). Additionally, there was no significant difference in moderate or severe bleeding events between the 2 groups.5 Efficacy and safety results were similar among a subgroup of patients who were randomized to treatment within 12 hours rather than 24 hours from symptom onset.16 The CHANCE trial was the first major study to demonstrate a clinical benefit of CLO-ASA to prevent recurrent stroke. Accordingly, the 2018 AHA/ASA guidelines included a new recommendation regarding secondary prevention for the use of CLO-ASA initiated within 24 hours and continued for 21 days following a minor stroke or TIA.11

A drawback of the CHANCE trial was its narrow patient population of only Chinese patients, which may limit applicability in clinical practice. There are known genetic variations in cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) that may affect clopidogrel metabolism. CYP2C19 is responsible for the conversion of clopidogrel into its activated form in vivo. Carriers of a CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele may have reduced clopidogrel activation and subsequent reduced antiplatelet activity. Such loss-of-function alleles are more common in Asian populations vs non-Asian populations.17

A substudy of CHANCE found that CLO-ASA’s efficacy benefit was preserved in noncarrier patients; however, patients with the CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele did not benefit from combination therapy.18 Interestingly, these genetic differences did not affect bleeding outcomes. Given that approximately 60% of patients in the CHANCE substudy were loss-of-function allele carriers and that the overall study results still showed benefit with combination therapy, application of CHANCE’s findings to broader populations may not be a concern after all.18

Continue to: In efforts to gain insight...

In efforts to gain insight on CLO-ASA’s use in a more diverse patient population, the POINT trial included almost 5000 patients, with 82% from the United States, who were randomized within 12 hours of symptom onset to CLO-ASA or aspirin monotherapy for 90 days.4 Similar to the CHANCE study, the POINT study included patients with mild ischemic strokes (NIHSS ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 ≥ 4). Combination therapy significantly reduced the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or death from an ischemic event. Contrary to CHANCE, there was a significant increase in major bleeding in those assigned to combination therapy, which resulted in the trial being stopped early.4

A closer look at safety differences. CHANCE and POINT were the first major trials to show a benefit of CLO-ASA for secondary prevention of stroke, yet their differences in safety outcomes, specifically major hemorrhage, argued for a deeper reconciliation of their results.4,5 While both trials initiated secondary prevention within 24 hours of symptom onset, the difference in duration of combination therapy (21 days in CHANCE vs 90 days in POINT) likely impacted the rates of hemorrhage. When results from POINT were stratified by time period, particularly within the first 30 days of therapy (similar to the 21-day treatment duration of CHANCE), combination therapy significantly reduced the primary endpoint of ischemic stroke, MI, or death from an ischemic event (3.9% CLO-ASA vs 5.8% aspirin; P = .02) without an increased risk for major hemorrhage. Between 30 and 90 days, this efficacy benefit disappeared. However, bleeding rates between groups continued to separate throughout the 90-day course. In this light, the 30-day outcomes of POINT are largely similar to CHANCE and support the short-term use of CLO-ASA for secondary prevention without an associated increase in major bleeding.4,5

Antiplatelet dosing in POINT and CHANCE may also play a role in the contrasting safety results between the trials.4,5 While both studies utilized clopidogrel loading doses, POINT used 600 mg while CHANCE used 300 mg. Clopidogrel maintenance dosing was the same at 75 mg/d. In CHANCE, aspirin dosing was protocolized to 75 mg/d; however, in POINT, 31% of patients used > 100 mg/d aspirin.4,5 It is possible that the higher doses of both aspirin and clopidogrel in the POINT trial contributed to the difference in the occurrence of major hemorrhage between the treatment groups in these trials.

The takeaway. Based on currently available data, patients who are best suited to benefit from CLO-ASA are those who have had minor noncardioembolic ischemic strokes or high-risk TIAs.4,5,11 Clopidogrel should be given as a 300-mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/d given concomitantly with aspirin at a dose no higher than 100 mg/d. CLO-ASA therapy should be initiated within 24 hours of symptom onset and be continued for no longer than 1 month, after which chronic preventive therapy with either aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy should be started.4,5,11

Dipyridamole and aspirin: A controversial option

Since the approval of the combination product ASA-ERDP, there has been considerable controversy about using this combination over other therapies, such as aspirin or clopidogrel, for recurrent ischemic stroke prevention. Much of this controversy arises from limitations in the trial designs.

Continue to: The first trial to show benefit...

The first trial to show benefit with ASA-ERDP was ESPS2 (European Stroke Prevention Study 2), which demonstrated superiority of the combination over placebo in reducing recurrent stroke when treatment was added within 3 months of an index stroke.19 A few studies have evaluated ASA-ERDP compared to aspirin monotherapy; however, most of these studies were small and did not show any difference in outcomes.20 Only ESPRIT (European/Australasian Stroke Prevention in Reversible Ischaemia Trial)21 carried significant weight in a 2013 meta-analysis, which showed a significant reduction in recurrent events with the combination product compared to aspirin monotherapy.20

Both the ESPS2 and ESPRIT trials had significant limitations.19,21 Patients in both studies had vascular comorbidities including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD); however, pharmacotherapies designated to treat these diseases were not mentioned in the demographic data, nor were these medications taken into consideration to limit potential bias.19,21 Retrospectively, a significant proportion of aspirin doses utilized as a control in ESPRIT were inferior to the guideline-recommended dosing with 42% to 46% of patients receiving 30 mg/d.21 Despite these controversies, ASA-ERDP is still considered an alternative to aspirin monotherapy in the guidelines.7

The timing of ASA-ERDP initiation appears to be inversely related to the efficacy of the combination over therapeutic alternatives. Studies in which the therapy was initiated 3 to 6 months from the index stroke indicated favorable outcomes for the combination when compared to ASA or ERDP monotherapy.19,21 Studies utilizing early initiation (ie, within 24 or 48 hours of the index event) or even within 3 weeks showed no difference in outcomes; however, this may be due in part to the use of clopidogrel or other combination antiplatelet therapy as active comparators.22-24

Early initiation of ASA-ERDP also demonstrated a higher risk of major and intracranial bleeding compared to clopidogrel.22 Additionally, use of triple therapy with ASA-ERDP plus clopidogrel increased bleeding events without improving efficacy.24 More recent studies of ASA-ERDP are focusing on earlier initiation of therapy; it is unknown whether the benefits of late initiation will be confirmed in future studies. Highlights of the major RCTs evaluating the safety and efficacy of ASA-ERDP are detailed in TABLE 219,21-24.

The takeaway. Methodological issues and potential confounding factors in many of the key trials for ASA-ERDP make it challenging to fully discern the role that ASA-ERDP may play in the secondary prevention of stroke. Further evidence utilizing appropriate controls, timing, and assessment of confounders is needed. Additionally, ASA-ERDP is plagued by tolerability issues such as headache, nausea, and vomiting, leading to higher rates of discontinuation than its comparators in clinical trials. Accordingly, the maintenance use of ASA-ERDP for secondary stroke prevention may be considered less preferred than other recommended alternatives such as aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapies.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert S. Helmer, PharmD, BCPS, Department of Pharmacy Practice, Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, 650 Clinic Drive, Suite 2100, Mobile, AL 36688; Rsh0011@auburn.edu.

1. CDC. Stroke Facts. Last updated January 31, 2020. www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

2. Amarenco P, Lavallee PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542.

3. Amarenco P, Lavallee PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2182-2190.

4. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215-225.

5. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11-19.

6. Bowry AD, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel plus aspirin as compared to antiplatelet monotherapy for the prevention of vascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:960-966.

7. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160-2236.

8. Gent M, Beaumont D, Blanchard J, et al. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet. 1996;348:1329-1339.

9. Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e601S-e636S.

10. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, et al. The acute stroke or transient ischemic attack treated with ticagrelor and aspirin for prevention of stroke and death (THALES) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2019;14:745‐751.

11. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110.

12. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331-337.

13. Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, et al. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:817-825.

14. Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Easton JD, et al. Effect of clopidogrel plus ASA vs. ASA early after TIA and ischaemic stroke: a substudy of the CHARISMA trial. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:3-9.

15. Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, et al. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961-969.

16. Li Z, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Treatment effect of clopidogrel plus aspirin within 12 hours of acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003038.

17. Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:317-323.

18. Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, et al. Association between CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele status and efficacy of clopidogrel for risk reduction among patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA. 2016;316:70-78.

19. Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, et al. European Stroke Prevention Study 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143:1-13.

20. Li X, Zhou G, Zhou X, et al. The efficacy and safety of aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin in secondary prevention following TIA or stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:92-96.

21. Halkes PH, van Gijn J, Kapelle IJ, et al. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1665-1673.

22. Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1238-1251.

23. Dengler R, Diener HC, Schwartz A, et al. Early treatment with aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole for transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke within 24 h of symptom onset (EARLY trial): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:159-166.

24. Bath PM, Woodhouse LJ, Appleton JP, et al. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole versus clopidogrel alone or aspirin and dipyridamole in patients with acute cerebral ischaemia (TARDIS): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:850-859.

1. CDC. Stroke Facts. Last updated January 31, 2020. www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

2. Amarenco P, Lavallee PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542.

3. Amarenco P, Lavallee PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. Five-year risk of stroke after TIA or minor ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2182-2190.

4. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215-225.

5. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11-19.

6. Bowry AD, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel plus aspirin as compared to antiplatelet monotherapy for the prevention of vascular events. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:960-966.

7. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160-2236.

8. Gent M, Beaumont D, Blanchard J, et al. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet. 1996;348:1329-1339.

9. Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e601S-e636S.

10. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Denison H, et al. The acute stroke or transient ischemic attack treated with ticagrelor and aspirin for prevention of stroke and death (THALES) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2019;14:745‐751.

11. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110.

12. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331-337.

13. Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, et al. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:817-825.

14. Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Easton JD, et al. Effect of clopidogrel plus ASA vs. ASA early after TIA and ischaemic stroke: a substudy of the CHARISMA trial. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:3-9.

15. Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, et al. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:961-969.

16. Li Z, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Treatment effect of clopidogrel plus aspirin within 12 hours of acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003038.

17. Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:317-323.

18. Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, et al. Association between CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele status and efficacy of clopidogrel for risk reduction among patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA. 2016;316:70-78.

19. Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, et al. European Stroke Prevention Study 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143:1-13.

20. Li X, Zhou G, Zhou X, et al. The efficacy and safety of aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin in secondary prevention following TIA or stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:92-96.

21. Halkes PH, van Gijn J, Kapelle IJ, et al. Aspirin plus dipyridamole versus aspirin alone after cerebral ischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1665-1673.

22. Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1238-1251.

23. Dengler R, Diener HC, Schwartz A, et al. Early treatment with aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole for transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke within 24 h of symptom onset (EARLY trial): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:159-166.

24. Bath PM, Woodhouse LJ, Appleton JP, et al. Antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole versus clopidogrel alone or aspirin and dipyridamole in patients with acute cerebral ischaemia (TARDIS): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:850-859.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Initiate combined clopidogrel plus aspirin within 24 hours of a minor stroke or TIA and continue for no longer than 1 month; then switch patients to aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy. A

› Do not use combined clopidogrel plus aspirin for long-term secondary stroke prevention. A

› Limit use of aspirin plus extended-release dipyridamole as a first choice for secondary stroke prevention because of limitations in efficacy and poor tolerability. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Part 4: Monitoring for CKD in Diabetes Patients

Previously, we discussed assessment and treatment for dyslipidemia in patients with diabetes. Now we’ll explore how to monitor for kidney disease in this population.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W’s basic metabolic panel includes an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 55 ml/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2). In the absence of any other markers of kidney disease, you obtain a spot urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). The UACR results show a ratio of 64 mg/g, confirming stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Monitoring for Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD is characterized by persistent albuminuria, low eGFR, and manifestations of kidney damage, and it increases cardiovascular risk.2 According to the ADA, clinicians should obtain a UACR and eGFR at least annually in patients who have had type 1 diabetes for at least 5 years and in all patients with type 2 diabetes.2 Monitoring is needed twice a year for those who begin to show signs of albuminuria or a reduced eGFR. This helps define the presence or stage of CKD and allows for further treatment planning.

Notably, patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2, an unclear cause of kidney disease, or signs of rapidly progressive disease (eg, decline in GFR category plus ≥ 25% decline in eGFR from baseline) should be seen by nephrology for further evaluation and treatment recommendations.2,36

Diabetes medications for kidney health. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists may be good candidates to promote kidney health in patients such as Mr. W. Recent trials show that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce the risk for progressive diabetic kidney disease, and the ADA recommends these medications for patients with CKD.2,16,36 GLP-1 receptor agonists also may be associated with a lower rate of development and progression of diabetic kidney disease, but this effect appears to be less robust.7,15,16 ADA guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for patients whose eGFR is adequate.37

ADA and AACE guidelines offer specific treatment recommendations on the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in the management of diabetes.10,37 Note that neither SGLT2 inhibitors nor GLP-1 agonists are strictly under the purview of endocrinologists. Rather, multiple guidelines state that they can be utilized safely by a variety of practitioners.6,38,39

In the concluding part of this series, we will explore how to screen for peripheral neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy—identification of which can improve the patient’s quality of life.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

Previously, we discussed assessment and treatment for dyslipidemia in patients with diabetes. Now we’ll explore how to monitor for kidney disease in this population.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W’s basic metabolic panel includes an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 55 ml/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2). In the absence of any other markers of kidney disease, you obtain a spot urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). The UACR results show a ratio of 64 mg/g, confirming stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Monitoring for Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD is characterized by persistent albuminuria, low eGFR, and manifestations of kidney damage, and it increases cardiovascular risk.2 According to the ADA, clinicians should obtain a UACR and eGFR at least annually in patients who have had type 1 diabetes for at least 5 years and in all patients with type 2 diabetes.2 Monitoring is needed twice a year for those who begin to show signs of albuminuria or a reduced eGFR. This helps define the presence or stage of CKD and allows for further treatment planning.

Notably, patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2, an unclear cause of kidney disease, or signs of rapidly progressive disease (eg, decline in GFR category plus ≥ 25% decline in eGFR from baseline) should be seen by nephrology for further evaluation and treatment recommendations.2,36

Diabetes medications for kidney health. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists may be good candidates to promote kidney health in patients such as Mr. W. Recent trials show that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce the risk for progressive diabetic kidney disease, and the ADA recommends these medications for patients with CKD.2,16,36 GLP-1 receptor agonists also may be associated with a lower rate of development and progression of diabetic kidney disease, but this effect appears to be less robust.7,15,16 ADA guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for patients whose eGFR is adequate.37

ADA and AACE guidelines offer specific treatment recommendations on the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in the management of diabetes.10,37 Note that neither SGLT2 inhibitors nor GLP-1 agonists are strictly under the purview of endocrinologists. Rather, multiple guidelines state that they can be utilized safely by a variety of practitioners.6,38,39

In the concluding part of this series, we will explore how to screen for peripheral neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy—identification of which can improve the patient’s quality of life.

Previously, we discussed assessment and treatment for dyslipidemia in patients with diabetes. Now we’ll explore how to monitor for kidney disease in this population.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W’s basic metabolic panel includes an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 55 ml/min/1.73 m2 (reference range, > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2). In the absence of any other markers of kidney disease, you obtain a spot urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR). The UACR results show a ratio of 64 mg/g, confirming stage 3 chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Monitoring for Chronic Kidney Disease

CKD is characterized by persistent albuminuria, low eGFR, and manifestations of kidney damage, and it increases cardiovascular risk.2 According to the ADA, clinicians should obtain a UACR and eGFR at least annually in patients who have had type 1 diabetes for at least 5 years and in all patients with type 2 diabetes.2 Monitoring is needed twice a year for those who begin to show signs of albuminuria or a reduced eGFR. This helps define the presence or stage of CKD and allows for further treatment planning.

Notably, patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2, an unclear cause of kidney disease, or signs of rapidly progressive disease (eg, decline in GFR category plus ≥ 25% decline in eGFR from baseline) should be seen by nephrology for further evaluation and treatment recommendations.2,36

Diabetes medications for kidney health. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists may be good candidates to promote kidney health in patients such as Mr. W. Recent trials show that SGLT2 inhibitors reduce the risk for progressive diabetic kidney disease, and the ADA recommends these medications for patients with CKD.2,16,36 GLP-1 receptor agonists also may be associated with a lower rate of development and progression of diabetic kidney disease, but this effect appears to be less robust.7,15,16 ADA guidelines recommend SGLT2 inhibitors for patients whose eGFR is adequate.37

ADA and AACE guidelines offer specific treatment recommendations on the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in the management of diabetes.10,37 Note that neither SGLT2 inhibitors nor GLP-1 agonists are strictly under the purview of endocrinologists. Rather, multiple guidelines state that they can be utilized safely by a variety of practitioners.6,38,39

In the concluding part of this series, we will explore how to screen for peripheral neuropathy and diabetic retinopathy—identification of which can improve the patient’s quality of life.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.