User login

DRESS Syndrome: Clinical Myths and Pearls

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

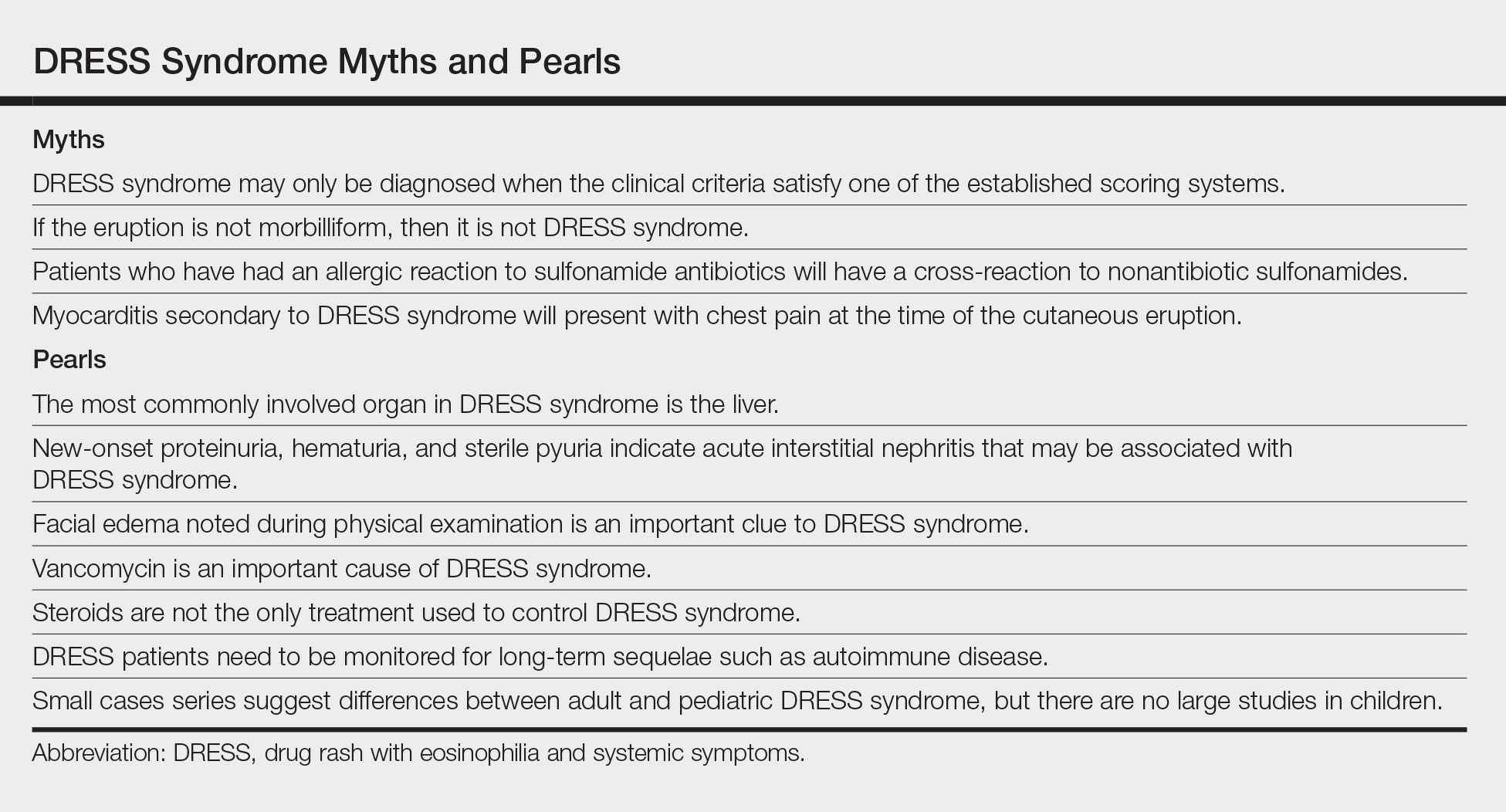

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

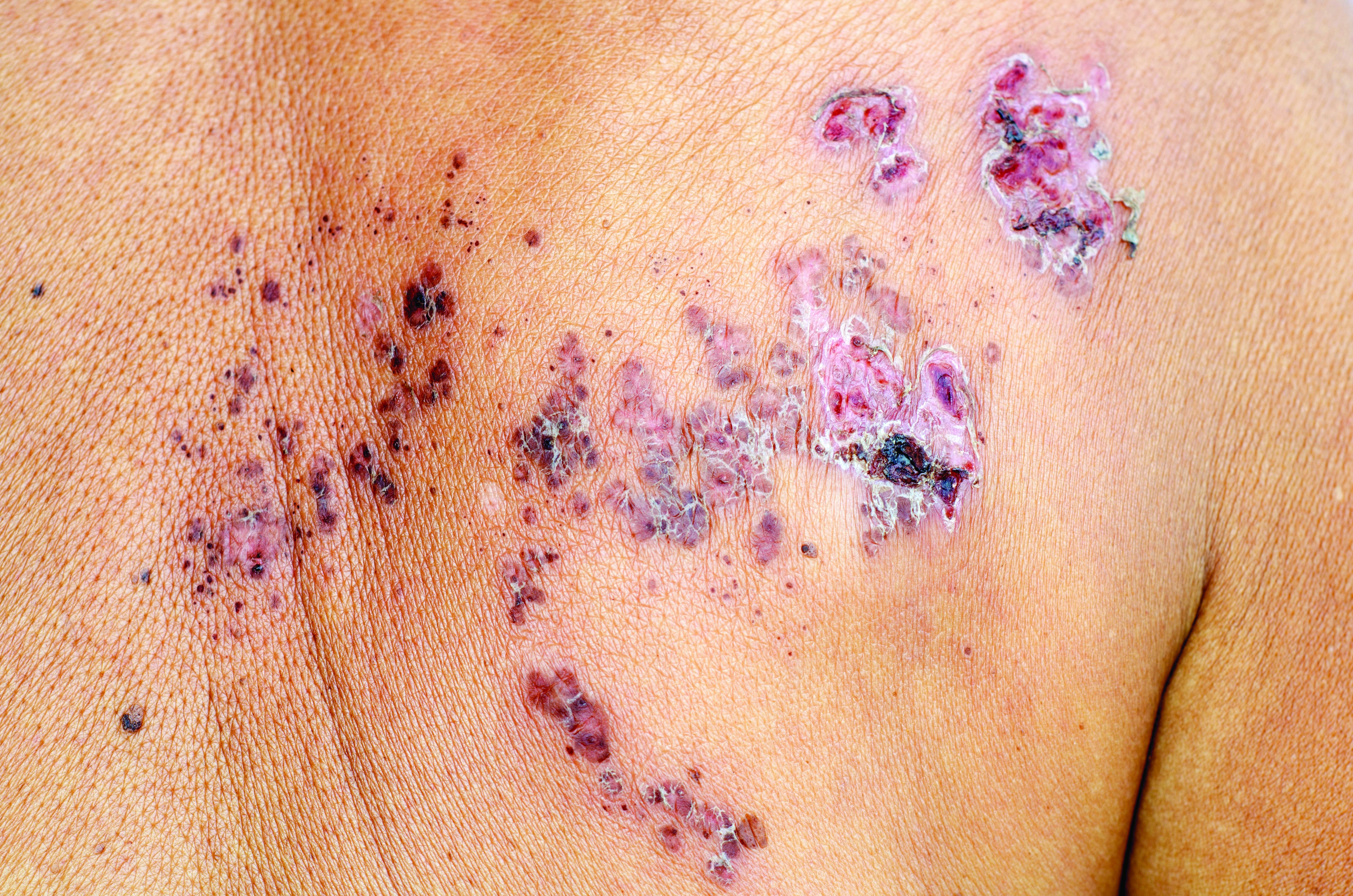

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13

Myth: Patients who have had an allergic reaction to sulfonamide antibiotics will have a cross-reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides.

A common question is, if a patient has had a prior allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, then are nonantibiotic sulfones such as a sulfonylurea, thiazide diuretic, or furosemide likely to cause a a cross-reaction? In one study (N=969), only 9.9% of patients with a prior sulfone antibiotic allergy developed hypersensitivity when exposed to a nonantibiotic sulfone, which is thought to be due to an overall increased propensity for hypersensitivity rather than a true cross-reaction. In fact, the risk for developing a hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (14.0% [717/5115]) was higher than the risk for developing a reaction from a nonantibiotic sulfone among these patients.14 This study bolsters the argument that if there are other potential culprit medications and the time course for a patient’s nonantibiotic sulfone is not consistent with the timeline for DRESS syndrome, it may be beneficial to look for a different causative agent.

Pearl: Vancomycin is an important cause of DRESS syndrome.

Guidelines for treating endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection recommend intravenous vancomycin for 4 to 6 weeks.15 This duration is within the relevant time frame of exposure for the development of DRESS syndrome de novo.

One case series noted that 37.5% (12/32) of DRESS syndrome cases in a 3-year period were caused by vancomycin, which notably was the most common medication associated with DRESS syndrome.16 There were caveats to this case series in that no standardized drug causality score was used and the sample size over the 3-year period was small; however, the increased use (and misuse) of antibiotics and perhaps increased recognition of rash in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics may play a role if vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome is indeed becoming more common.

Myth: Myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome will present with chest pain at the time of the cutaneous eruption.

Few patients with DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis actually are symptomatic during their hospitalization.4 In asymptomatic patients, the primary team and consultants should be vigilant for the potential of subclinical myocarditis or the possibility of developing cardiac involvement after discharge, as myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome may present any time from rash onset up to 4 months later.4 Therefore, DRESS patients should be especially attentive to any new cardiac symptoms and notify their provider if any develop.

Although no standard cardiac screening guidelines exist for DRESS syndrome, some have recommended that baseline cardiac screening tests including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, and echocardiogram be considered at the time of diagnosis.5 If any testing is abnormal, DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis should be suspected and an endomyocardial biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, may be necessary.4 If the cardiac screening tests are normal, some investigators recommend serial outpatient echocardiograms for all DRESS patients, even those who remain asymptomatic.17 An alternative is an empiric approach in which a thorough review of systems is performed and testing is done if patients develop symptoms that are concerning for myocarditis.

Pearl: Steroids are not the only treatment used to control DRESS syndrome.

A prolonged taper of systemic steroids is the first-line treatment of DRESS syndrome. Steroids at the equivalent of 1 to 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) of prednisone typically are used. For severe and/or recalcitrant DRESS syndrome, 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) typically is used, and less than 1 mg/kg daily may be used for mini-DRESS syndrome.

Clinical improvement of DRESS syndrome has been demonstrated in several case reports with intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis.18-21 Each of these therapies typically were initiated as second-line therapeutic agents when initial treatment with steroids failed. It is important to note that large prospective studies regarding these treatments are lacking; however, there have been case reports of acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis that did not respond to the combination of steroids and cyclosporine.4,22

Although there have been successful case reports using intravenous immunoglobulin, a 2012 prospective open-label clinical trial reported notable side effects in 5 of 6 (83.3%) patients with only 1 of 6 (16.6%) achieving the primary end point of control of fever/symptoms at day 7 and clinical remission without steroids on day 30.23

Pearl: DRESS patients need to be monitored for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disease.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as a delayed complication of DRESS syndrome, including autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.24-26 Incidence rates of autoimmunity following DRESS syndrome range from 3% to 5% among small case series.24,25

Autoimmune thyroiditis, which may present as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or painless thyroiditis, is the most common autoimmune disorder to develop in DRESS patients and appears from several weeks to up to 3 years after DRESS.24 Therefore, all DRESS patients should be monitored longitudinally for several years for signs or symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune condition.5,24,26

Because no guidelines exist regarding serial monitoring for autoimmune sequelae, it may be reasonable to check thyroid function tests at the time of diagnosis and regularly for at least 2 years after diagnosis.5 Alternatively, clinicians may consider an empiric approach to laboratory testing that is guided by the development of clinical symptoms.

Pearl: Small cases series suggest differences between adult and pediatric DRESS syndrome, but there are no large studies in children.

Small case series have suggested there may be noteworthy differences between DRESS syndrome in adults and children. Although human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) positivity in DRESS syndrome in adults may be as high as 80%, 13% of pediatric patients in one cohort tested positive for HHV-6, though the study size was limited at 29 total patients.27 In children, DRESS syndrome secondary to antibiotics was associated with a shorter latency time as compared to cases secondary to nonantibiotics. In contrast to the typical 2- to 6-week timeline, Sasidharanpillai et al28 reported an average onset 5.8 days after drug administration in antibiotic-associated DRESS syndrome compared to 23.9 days for anticonvulsants, though this study only included 11 total patients. Other reports have suggested a similar trend.27

The role of HHV-6 positivity in pediatric DRESS syndrome and its influence on prognosis remains unclear. One study showed a worse prognosis for pediatric patients with positive HHV-6 antibodies.27 However, with such a small sample size—only 4 HHV-6–positive patients of 29 pediatric DRESS cases—larger studies are needed to better characterize the relationship between HHV-6 positivity and prognosis.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med, 2011;124:588-597.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Intarasupht J, Kanchanomai A, Leelasattakul W, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and mortality outcome in the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients with cardiac involvement. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1187-1191.

- Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, et al. A review of DRESS-associated myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E229-E236.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-693.e14; quiz 706-708.

- Lee T, Lee YS, Yoon SY, et al. Characteristics of liver injury in drug-induced systemic hypersensitivity reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:407-415.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422-428.

- Walsh S, Diaz-Cano S, Higgins E, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? a review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:149-162.

- Matsuda H, Saito K, Takayanagi Y, et al. Pustular-type drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to carbamazepine with systemic muscle involvement. J Dermatol. 2013;40:118-122.

- Wolf R, Davidovici B, Matz H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms versus Stevens-Johnson Syndrome—a case that indicates a stumbling block in the current classification. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:308-310.

- Kumar A, Goldfarb JW, Bittner EA. A case of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome complicating airway management. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:295-298.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1628-1635.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:E26-E46.

- Lam BD, Miller MM, Sutton AV, et al. Vancomycin and DRESS: a retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-975.

- Eppenberger M, Hack D, Ammann P, et al. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis with dramatic response to steroid therapy: the central role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow-up. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:326-330.

- Kirchhof MG, Wong A, Dutz JP. Cyclosporine treatment of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1254-1257.

- Singer EM, Wanat KA, Rosenbach MA. A case of recalcitrant DRESS syndrome with multiple autoimmune sequelae treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:494-495.

- Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, et al. Management of psychotropic drug-induced DRESS syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:787-801.

- Alexander T, Iglesia E, Park Y, et al. Severe DRESS syndrome managed with therapeutic plasma exchange. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E945-E949.

- Daoulah A, Alqahtani AA, Ocheltree SR, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 56-year-old female patient treated with sulfasalazine. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:638.e1-638.e3.

- Joly P, Janela B, Tetart F, et al. Poor benefit/risk balance of intravenous immunoglobulins in DRESS. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:543-544.

- Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42:276-282.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:721-728.

- Matta JM, Flores SM, Cherit JD. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and its relation with autoimmunity in a reference center in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:30-33.

- Ahluwalia J, Abuabara K, Perman MJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 involvement in paediatric drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1090-1095.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13

Myth: Patients who have had an allergic reaction to sulfonamide antibiotics will have a cross-reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides.

A common question is, if a patient has had a prior allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, then are nonantibiotic sulfones such as a sulfonylurea, thiazide diuretic, or furosemide likely to cause a a cross-reaction? In one study (N=969), only 9.9% of patients with a prior sulfone antibiotic allergy developed hypersensitivity when exposed to a nonantibiotic sulfone, which is thought to be due to an overall increased propensity for hypersensitivity rather than a true cross-reaction. In fact, the risk for developing a hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (14.0% [717/5115]) was higher than the risk for developing a reaction from a nonantibiotic sulfone among these patients.14 This study bolsters the argument that if there are other potential culprit medications and the time course for a patient’s nonantibiotic sulfone is not consistent with the timeline for DRESS syndrome, it may be beneficial to look for a different causative agent.

Pearl: Vancomycin is an important cause of DRESS syndrome.

Guidelines for treating endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection recommend intravenous vancomycin for 4 to 6 weeks.15 This duration is within the relevant time frame of exposure for the development of DRESS syndrome de novo.

One case series noted that 37.5% (12/32) of DRESS syndrome cases in a 3-year period were caused by vancomycin, which notably was the most common medication associated with DRESS syndrome.16 There were caveats to this case series in that no standardized drug causality score was used and the sample size over the 3-year period was small; however, the increased use (and misuse) of antibiotics and perhaps increased recognition of rash in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics may play a role if vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome is indeed becoming more common.

Myth: Myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome will present with chest pain at the time of the cutaneous eruption.

Few patients with DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis actually are symptomatic during their hospitalization.4 In asymptomatic patients, the primary team and consultants should be vigilant for the potential of subclinical myocarditis or the possibility of developing cardiac involvement after discharge, as myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome may present any time from rash onset up to 4 months later.4 Therefore, DRESS patients should be especially attentive to any new cardiac symptoms and notify their provider if any develop.

Although no standard cardiac screening guidelines exist for DRESS syndrome, some have recommended that baseline cardiac screening tests including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, and echocardiogram be considered at the time of diagnosis.5 If any testing is abnormal, DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis should be suspected and an endomyocardial biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, may be necessary.4 If the cardiac screening tests are normal, some investigators recommend serial outpatient echocardiograms for all DRESS patients, even those who remain asymptomatic.17 An alternative is an empiric approach in which a thorough review of systems is performed and testing is done if patients develop symptoms that are concerning for myocarditis.

Pearl: Steroids are not the only treatment used to control DRESS syndrome.

A prolonged taper of systemic steroids is the first-line treatment of DRESS syndrome. Steroids at the equivalent of 1 to 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) of prednisone typically are used. For severe and/or recalcitrant DRESS syndrome, 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) typically is used, and less than 1 mg/kg daily may be used for mini-DRESS syndrome.

Clinical improvement of DRESS syndrome has been demonstrated in several case reports with intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis.18-21 Each of these therapies typically were initiated as second-line therapeutic agents when initial treatment with steroids failed. It is important to note that large prospective studies regarding these treatments are lacking; however, there have been case reports of acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis that did not respond to the combination of steroids and cyclosporine.4,22

Although there have been successful case reports using intravenous immunoglobulin, a 2012 prospective open-label clinical trial reported notable side effects in 5 of 6 (83.3%) patients with only 1 of 6 (16.6%) achieving the primary end point of control of fever/symptoms at day 7 and clinical remission without steroids on day 30.23

Pearl: DRESS patients need to be monitored for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disease.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as a delayed complication of DRESS syndrome, including autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.24-26 Incidence rates of autoimmunity following DRESS syndrome range from 3% to 5% among small case series.24,25

Autoimmune thyroiditis, which may present as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or painless thyroiditis, is the most common autoimmune disorder to develop in DRESS patients and appears from several weeks to up to 3 years after DRESS.24 Therefore, all DRESS patients should be monitored longitudinally for several years for signs or symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune condition.5,24,26

Because no guidelines exist regarding serial monitoring for autoimmune sequelae, it may be reasonable to check thyroid function tests at the time of diagnosis and regularly for at least 2 years after diagnosis.5 Alternatively, clinicians may consider an empiric approach to laboratory testing that is guided by the development of clinical symptoms.

Pearl: Small cases series suggest differences between adult and pediatric DRESS syndrome, but there are no large studies in children.

Small case series have suggested there may be noteworthy differences between DRESS syndrome in adults and children. Although human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) positivity in DRESS syndrome in adults may be as high as 80%, 13% of pediatric patients in one cohort tested positive for HHV-6, though the study size was limited at 29 total patients.27 In children, DRESS syndrome secondary to antibiotics was associated with a shorter latency time as compared to cases secondary to nonantibiotics. In contrast to the typical 2- to 6-week timeline, Sasidharanpillai et al28 reported an average onset 5.8 days after drug administration in antibiotic-associated DRESS syndrome compared to 23.9 days for anticonvulsants, though this study only included 11 total patients. Other reports have suggested a similar trend.27

The role of HHV-6 positivity in pediatric DRESS syndrome and its influence on prognosis remains unclear. One study showed a worse prognosis for pediatric patients with positive HHV-6 antibodies.27 However, with such a small sample size—only 4 HHV-6–positive patients of 29 pediatric DRESS cases—larger studies are needed to better characterize the relationship between HHV-6 positivity and prognosis.

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13

Myth: Patients who have had an allergic reaction to sulfonamide antibiotics will have a cross-reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides.

A common question is, if a patient has had a prior allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, then are nonantibiotic sulfones such as a sulfonylurea, thiazide diuretic, or furosemide likely to cause a a cross-reaction? In one study (N=969), only 9.9% of patients with a prior sulfone antibiotic allergy developed hypersensitivity when exposed to a nonantibiotic sulfone, which is thought to be due to an overall increased propensity for hypersensitivity rather than a true cross-reaction. In fact, the risk for developing a hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (14.0% [717/5115]) was higher than the risk for developing a reaction from a nonantibiotic sulfone among these patients.14 This study bolsters the argument that if there are other potential culprit medications and the time course for a patient’s nonantibiotic sulfone is not consistent with the timeline for DRESS syndrome, it may be beneficial to look for a different causative agent.

Pearl: Vancomycin is an important cause of DRESS syndrome.

Guidelines for treating endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection recommend intravenous vancomycin for 4 to 6 weeks.15 This duration is within the relevant time frame of exposure for the development of DRESS syndrome de novo.

One case series noted that 37.5% (12/32) of DRESS syndrome cases in a 3-year period were caused by vancomycin, which notably was the most common medication associated with DRESS syndrome.16 There were caveats to this case series in that no standardized drug causality score was used and the sample size over the 3-year period was small; however, the increased use (and misuse) of antibiotics and perhaps increased recognition of rash in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics may play a role if vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome is indeed becoming more common.

Myth: Myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome will present with chest pain at the time of the cutaneous eruption.

Few patients with DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis actually are symptomatic during their hospitalization.4 In asymptomatic patients, the primary team and consultants should be vigilant for the potential of subclinical myocarditis or the possibility of developing cardiac involvement after discharge, as myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome may present any time from rash onset up to 4 months later.4 Therefore, DRESS patients should be especially attentive to any new cardiac symptoms and notify their provider if any develop.

Although no standard cardiac screening guidelines exist for DRESS syndrome, some have recommended that baseline cardiac screening tests including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, and echocardiogram be considered at the time of diagnosis.5 If any testing is abnormal, DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis should be suspected and an endomyocardial biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, may be necessary.4 If the cardiac screening tests are normal, some investigators recommend serial outpatient echocardiograms for all DRESS patients, even those who remain asymptomatic.17 An alternative is an empiric approach in which a thorough review of systems is performed and testing is done if patients develop symptoms that are concerning for myocarditis.

Pearl: Steroids are not the only treatment used to control DRESS syndrome.

A prolonged taper of systemic steroids is the first-line treatment of DRESS syndrome. Steroids at the equivalent of 1 to 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) of prednisone typically are used. For severe and/or recalcitrant DRESS syndrome, 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) typically is used, and less than 1 mg/kg daily may be used for mini-DRESS syndrome.

Clinical improvement of DRESS syndrome has been demonstrated in several case reports with intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis.18-21 Each of these therapies typically were initiated as second-line therapeutic agents when initial treatment with steroids failed. It is important to note that large prospective studies regarding these treatments are lacking; however, there have been case reports of acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis that did not respond to the combination of steroids and cyclosporine.4,22

Although there have been successful case reports using intravenous immunoglobulin, a 2012 prospective open-label clinical trial reported notable side effects in 5 of 6 (83.3%) patients with only 1 of 6 (16.6%) achieving the primary end point of control of fever/symptoms at day 7 and clinical remission without steroids on day 30.23

Pearl: DRESS patients need to be monitored for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disease.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as a delayed complication of DRESS syndrome, including autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.24-26 Incidence rates of autoimmunity following DRESS syndrome range from 3% to 5% among small case series.24,25

Autoimmune thyroiditis, which may present as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or painless thyroiditis, is the most common autoimmune disorder to develop in DRESS patients and appears from several weeks to up to 3 years after DRESS.24 Therefore, all DRESS patients should be monitored longitudinally for several years for signs or symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune condition.5,24,26

Because no guidelines exist regarding serial monitoring for autoimmune sequelae, it may be reasonable to check thyroid function tests at the time of diagnosis and regularly for at least 2 years after diagnosis.5 Alternatively, clinicians may consider an empiric approach to laboratory testing that is guided by the development of clinical symptoms.

Pearl: Small cases series suggest differences between adult and pediatric DRESS syndrome, but there are no large studies in children.

Small case series have suggested there may be noteworthy differences between DRESS syndrome in adults and children. Although human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) positivity in DRESS syndrome in adults may be as high as 80%, 13% of pediatric patients in one cohort tested positive for HHV-6, though the study size was limited at 29 total patients.27 In children, DRESS syndrome secondary to antibiotics was associated with a shorter latency time as compared to cases secondary to nonantibiotics. In contrast to the typical 2- to 6-week timeline, Sasidharanpillai et al28 reported an average onset 5.8 days after drug administration in antibiotic-associated DRESS syndrome compared to 23.9 days for anticonvulsants, though this study only included 11 total patients. Other reports have suggested a similar trend.27

The role of HHV-6 positivity in pediatric DRESS syndrome and its influence on prognosis remains unclear. One study showed a worse prognosis for pediatric patients with positive HHV-6 antibodies.27 However, with such a small sample size—only 4 HHV-6–positive patients of 29 pediatric DRESS cases—larger studies are needed to better characterize the relationship between HHV-6 positivity and prognosis.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med, 2011;124:588-597.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Intarasupht J, Kanchanomai A, Leelasattakul W, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and mortality outcome in the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients with cardiac involvement. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1187-1191.

- Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, et al. A review of DRESS-associated myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E229-E236.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-693.e14; quiz 706-708.

- Lee T, Lee YS, Yoon SY, et al. Characteristics of liver injury in drug-induced systemic hypersensitivity reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:407-415.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422-428.

- Walsh S, Diaz-Cano S, Higgins E, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? a review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:149-162.

- Matsuda H, Saito K, Takayanagi Y, et al. Pustular-type drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to carbamazepine with systemic muscle involvement. J Dermatol. 2013;40:118-122.

- Wolf R, Davidovici B, Matz H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms versus Stevens-Johnson Syndrome—a case that indicates a stumbling block in the current classification. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:308-310.

- Kumar A, Goldfarb JW, Bittner EA. A case of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome complicating airway management. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:295-298.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1628-1635.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:E26-E46.

- Lam BD, Miller MM, Sutton AV, et al. Vancomycin and DRESS: a retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-975.

- Eppenberger M, Hack D, Ammann P, et al. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis with dramatic response to steroid therapy: the central role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow-up. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:326-330.

- Kirchhof MG, Wong A, Dutz JP. Cyclosporine treatment of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1254-1257.

- Singer EM, Wanat KA, Rosenbach MA. A case of recalcitrant DRESS syndrome with multiple autoimmune sequelae treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:494-495.

- Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, et al. Management of psychotropic drug-induced DRESS syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:787-801.

- Alexander T, Iglesia E, Park Y, et al. Severe DRESS syndrome managed with therapeutic plasma exchange. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E945-E949.

- Daoulah A, Alqahtani AA, Ocheltree SR, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 56-year-old female patient treated with sulfasalazine. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:638.e1-638.e3.

- Joly P, Janela B, Tetart F, et al. Poor benefit/risk balance of intravenous immunoglobulins in DRESS. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:543-544.

- Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42:276-282.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:721-728.

- Matta JM, Flores SM, Cherit JD. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and its relation with autoimmunity in a reference center in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:30-33.

- Ahluwalia J, Abuabara K, Perman MJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 involvement in paediatric drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1090-1095.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med, 2011;124:588-597.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Intarasupht J, Kanchanomai A, Leelasattakul W, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and mortality outcome in the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients with cardiac involvement. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1187-1191.

- Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, et al. A review of DRESS-associated myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E229-E236.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-693.e14; quiz 706-708.

- Lee T, Lee YS, Yoon SY, et al. Characteristics of liver injury in drug-induced systemic hypersensitivity reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:407-415.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422-428.

- Walsh S, Diaz-Cano S, Higgins E, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? a review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:149-162.

- Matsuda H, Saito K, Takayanagi Y, et al. Pustular-type drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to carbamazepine with systemic muscle involvement. J Dermatol. 2013;40:118-122.

- Wolf R, Davidovici B, Matz H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms versus Stevens-Johnson Syndrome—a case that indicates a stumbling block in the current classification. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:308-310.

- Kumar A, Goldfarb JW, Bittner EA. A case of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome complicating airway management. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:295-298.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1628-1635.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:E26-E46.

- Lam BD, Miller MM, Sutton AV, et al. Vancomycin and DRESS: a retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-975.

- Eppenberger M, Hack D, Ammann P, et al. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis with dramatic response to steroid therapy: the central role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow-up. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:326-330.

- Kirchhof MG, Wong A, Dutz JP. Cyclosporine treatment of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1254-1257.

- Singer EM, Wanat KA, Rosenbach MA. A case of recalcitrant DRESS syndrome with multiple autoimmune sequelae treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:494-495.

- Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, et al. Management of psychotropic drug-induced DRESS syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:787-801.

- Alexander T, Iglesia E, Park Y, et al. Severe DRESS syndrome managed with therapeutic plasma exchange. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E945-E949.

- Daoulah A, Alqahtani AA, Ocheltree SR, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 56-year-old female patient treated with sulfasalazine. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:638.e1-638.e3.

- Joly P, Janela B, Tetart F, et al. Poor benefit/risk balance of intravenous immunoglobulins in DRESS. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:543-544.

- Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42:276-282.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:721-728.

- Matta JM, Flores SM, Cherit JD. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and its relation with autoimmunity in a reference center in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:30-33.

- Ahluwalia J, Abuabara K, Perman MJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 involvement in paediatric drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1090-1095.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

Practice Points

- Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome) is a clinical diagnosis, and incomplete forms may not meet formal criteria-based diagnosis.

- Although DRESS syndrome typically has a morbilliform eruption, different rash morphologies may be observed.

- The myocarditis of DRESS syndrome may not present with chest pain; a high index of suspicion is warranted.

- Autoimmune sequelae are more frequent in patients who have had an episode of DRESS syndrome.

2018 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

Uterine fibroids are the most common solid pelvic tumor in women and a leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States.1 As a result, they represent significant morbidity for many women and are a major public health problem. By age 50, 70% of white women and 80% of black women have fibroids.2

Although fibroids are sometimes asymptomatic, the symptoms most commonly reported are abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) with resultant anemia and bulk/pressure symptoms. Uterine fibroids also are associated with reproductive dysfunction, such as recurrent pregnancy loss, and even infertility.3

The clinical diagnosis of uterine fibroids is made based on a combination of physical examination and imaging studies, including pelvic ultrasonography, saline infusion sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When medical management, such as combination oral contraceptive pills, fails in patients with AUB and/or bulk predominant symptoms or patients present with compromised fertility, the only option for conservative surgical management is a myomectomy.4

The route of myomectomy—hysteroscopy, laparotomy, conventional laparoscopic myomectomy (LM), or robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy (RALM)—depends on the size, number, location, and consistency of the uterine fibroids and, to a certain extent, the indication for the myomectomy. In some cases, multiple routes must be used to achieve optimal results, and sometimes these procedures have to be staged. In this literature review and technical summary, we focus on conventional LM and RALM approaches.

Literature review: In the right hands, LM and RALM have clear benefits

In the past, laparotomy was the surgical route of choice for fibroid removal. This surgery was associated with a long hospital stay, a high rate of blood transfusions, postoperative pain, and a lengthy recovery period. As minimally invasive surgery gained popularity, conventional LM became more commonly performed and was accepted by many as the gold standard approach for myomectomy.5

LM has considerable advantages over laparotomy

Compared with the traditional, more invasive route, the conventional LM approach has many benefits. These include less blood loss, decreased postoperative pain, shorter recovery time, shorter hospitalization stay, and decreased perioperative complications.6 LM should be considered the first-line approach unless the size of an intramural myoma exceeds 10 to 12 cm or multiple myomas (consensus, approximately 4 or more) are present and necessitate several incisions according to their varying locations within the uterus.7,8 While this is a recommendation, reports have been published on the successful laparoscopic approach to myomas larger than 20 cm, demonstrating that a skilled, experienced surgeon can perform this procedure safely.9-11

Many studies comparing LM with the abdominal approach showed that LM is associated with decreased blood loss, less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, and quicker recovery.12-14 Unfortunately, myomectomy via conventional laparoscopy can be technically challenging, thereby limiting patient accessibility to this approach. Major challenges with conventional LM include enucleation of the fibroid along the correct plane and a multilayered hysterotomy closure.15 The obvious concern with the latter is the potential risk for uterine rupture when improperly performed as a result of deficient suturing skills. Accordingly, several cases of uterine rupture in the second and third trimester of pregnancy after LM led to recommendations for stricter selection criteria, which excluded patients with fibroids larger than 5 cm, multiple fibroids, and deep intramural fibroids.16

Continue to: The RALM approach

The RALM approach

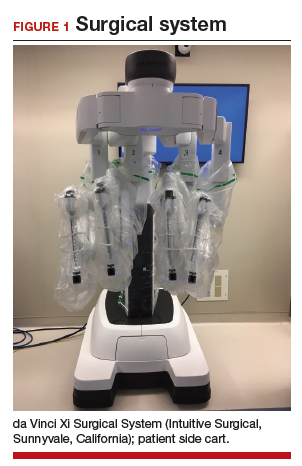

RALM was developed as a surgical alternative and to help overcome conventional laparoscopy challenges, such as suturing, as well as to offer minimally invasive options to a broader patient pool. In 2004, Advincula and colleagues reported the first case series of 35 women who underwent RALM.17 Since that report was published, multiple retrospective studies have confirmed RALM’s safety, feasibility, and efficacy.

How RALM stacks up against laparotomy. Compared with traditional abdominal myomectomy (AM), RALM has been associated with less blood loss, shorter hospital stay, quicker recovery time, fewer complications, and higher costs.18 In a comparative analysis of surgical outcomes and costs of RALM versus AM, Nash and colleagues found that RALM patients required less intravenous narcotics, had shorter hospital stays, and had equivalent clinical outcomes compared with AM-treated patients.19 In addition, the authors observed a correlation between increased specimen size and decreased operative efficiency with RALM. Retrospective cohort studies by Mansour and colleagues and Sangha and colleagues echoed similar conclusions.20,21

RALM versus conventional LM. The comparisons between conventional LM and RALM are not as clear-cut, and although evidence strongly suggests a role for RALM, more comparative studies are needed.

In 2013, Pundir and colleagues completed a meta-analysis and systematic review comparing RALM with AM and LM.22 They reviewed 10 observational studies; 7 compared RALM with AM, 4 compared RALM with LM, and 1 study compared RALM with AM and LM (this was included in both groups). In the comparison between RALM and AM, estimated blood loss, blood transfusion, and length of hospital stay were significantly lower with RALM, risk of complication was similar, and operating time and costs were significantly higher. The cost findings were not too dissimilar to conclusions drawn by Advincula and colleagues in an earlier study.18

Further, when Pundir and colleagues compared RALM with LM, blood transfusion risk and costs were higher with RALM, but no significant differences were noted in estimated blood loss, operating time, length of hospital stay, and complications.22 In this analysis, RALM showed significant short-term benefits when compared with AM but no benefit when compared with LM.

Continue to: Benefits after RALM over time

Benefits after RALM over time

Long-term benefits from RALM, such as symptom recurrence rates and fertility outcomes, have been demonstrated. In 2015, Pitter and colleagues published the first paper on symptom recurrence after RALM.23 In this retrospective survey, 426 women underwent RALM for symptom relief or infertility across 3 practice sites; 62.9% reported being symptom free after 3 years. In addition, 80% of symptom-free women who had undergone RALM to improve fertility outcomes conceived after 3 years. The mean (SD) time to pregnancy was 7.9 (9.4) months. Overall, pregnancy rates improved and symptom recurrence increased with the interval of time since surgery.23

In another study, Pitter and colleagues reported on pregnancy outcomes in greater detail.24 They evaluated 872 women who underwent RALM between October 2005 and November 2010 at 3 centers. Of these women, 107 conceived, resulting in 127 pregnancies and 92 deliveries through 2011. The means (SD) for age at myomectomy, number of myomas removed, and myoma size were 34.8 (4.5) years, 3.9 (3.2), and 7.5 (3.0) cm (weight, 191.7 [144.8] g), respectively. Overall, the pregnancy outcomes in this study were comparable to those reported in the literature for conventional LM.

Cela and colleagues reported similar outcomes based on their review of 48 patients who underwent RALM between 2007 and 2011.25 Seven women became pregnant (8 pregnancies). There were no spontaneous abortions or uterine ruptures. Following suit, Kang and colleagues reported outcomes in 100 women who underwent RALM for deep intramural fibroids (FIGO type 2 to 5).26 The average (SD) number of fibroids was 3.8 (3.5) with a mean (SD) size of 7.5 (2.1) cm. All patients recovered without major complications, and 75% of those pursuing pregnancy conceived.

The importance of LM and RALM

After this brief review of the data on conventional LM and RALM, it is fair to conclude that both surgical options are a game changer for the minimally invasive management of uterine fibroids. Despite strong evidence that suggests laparoscopy is superior to laparotomy for myomectomy, the technical demands required for performing conventional LM may explain why it is underutilized and why the advantages of robotic surgery—with its 3-dimensional imaging and articulated instruments—make this approach an attractive alternative.

The myomectomy technique we prefer at our institution

At our medical center, we approach the majority of abdominal myomectomies via conventional LM or RALM. We carefully select candidates with the goal of ensuring a successful procedure and minimizing the risk of conversion. When selecting candidates, we consider these factors:

- size, number, location, and consistency of the fibroids

- patient’s body habitus, and

- relative size of the uterus to the length of the patient’s torso.

Additionally, any concerns raised during the preoperative workup regarding a suspected risk of occult leiomyosarcoma preclude a minimally invasive approach. Otherwise, deciding between

conventional LM and RALM is based on surgeon preference.

View these surgical techniques on the multimedia channel

Robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy

Arnold P. Advincula, MD, Victoria M. Fratto, MD, and Caroline Key

A systematic approach to surgery in a 39-year-old woman with heavy menstrual bleeding who desires future fertility. Features include robot-specific techniques that facilitate fibroid enucleation and hysterotomy repair and demonstration of the ExCITE technique for tissue extraction.

Laparoscopic myomectomy technique

William H. Parker, MD

A step-by-step demonstration of the laparoscopic myomectomy technique used to resect a 7-cm posterior fibroid in a 44-year-old woman.

Laparoscopic myomectomy with enclosed transvaginal tissue extraction

Ceana Nezhat, MD, and Erica Dun, MD, MPH

A surgical case of a 41-yearold woman with radiating lower abdominal pain and menorrhagia who desired removal of symptomatic myomas. Preoperative transvaginal ultrasonography revealed a 4-cm posterior pedunculated myoma and a 5-cm fundal intramural myoma.

Continue to: Preoperative MRI guides surgical approach

Preoperative MRI guides surgical approach

An MRI scan is a critical component of the patient’s preoperative evaluation. It helps to define the uterine architecture as it relates to fibroids and to rule out the presence of adenomyosis. In general, we do not offer RALM to patients who have more than 15 myomas, a single myoma that is larger than 12 to 15 cm, or when the uterus is more than 2 fingerbreadths above the umbilicus (unless the patient’s torso allows for an adequate insufflated workspace). We also try to avoid preoperative treatment with a gonadotropin–releasing hormone agonist to minimize softening of the myoma and blurring of the dissection planes.

Steps in the procedure

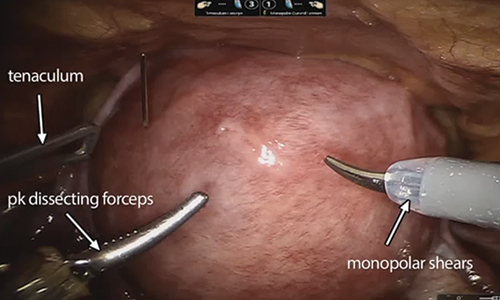

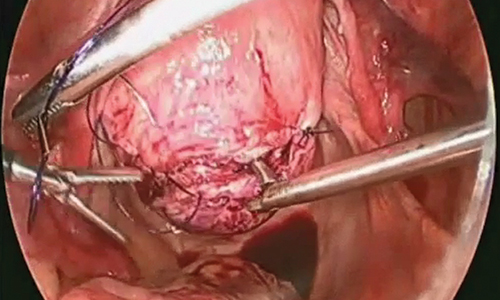

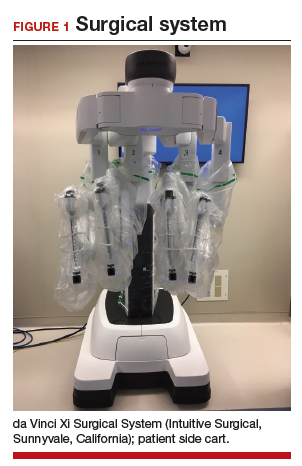

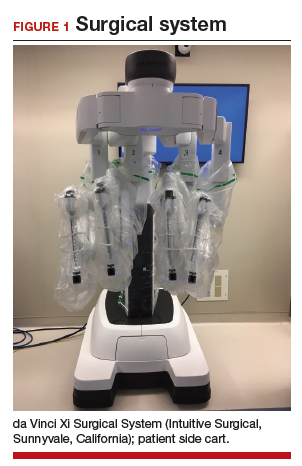

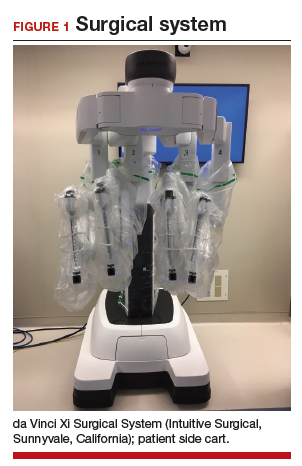

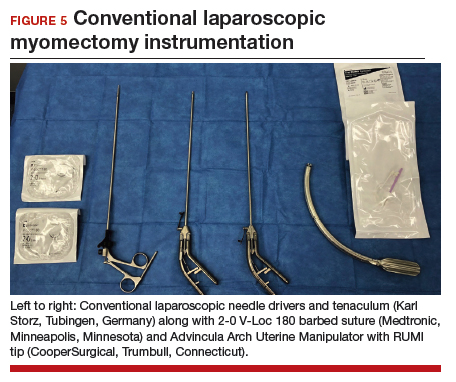

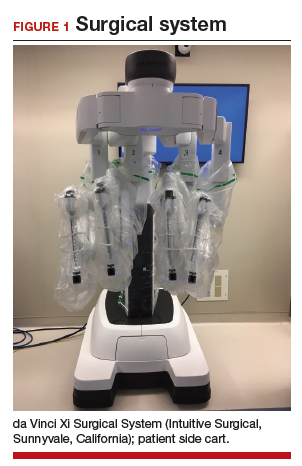

Once the patient is intubated, properly positioned, prepped, and draped, we turn our attention toward peritoneal entry. Factors that influence entry include the patient’s surgical history, radiologic imaging, physical examination (particularly the exam under anesthesia), and surgeon preference for optimizing access. Quite often we use a left upper quadrant entry via Palmer’s point, with subsequent port placement individualized to the patient’s pathology and abdominal topography. Three or more incisions are required to accommodate the camera and at least 2 to 3 operative instruments. Port sizes vary from 5 to 12 mm depending on the desired equipment and surgeon preference (conventional LM versus RALM [FIGURE 1]).

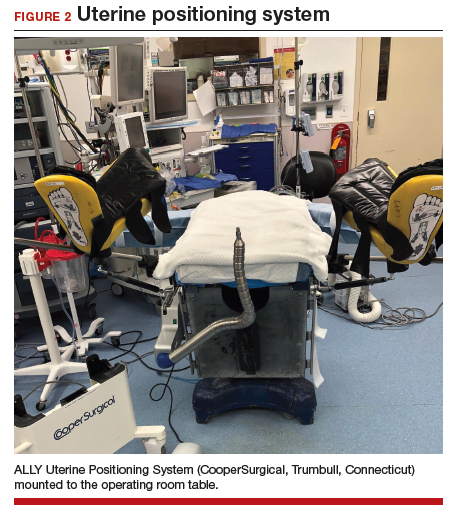

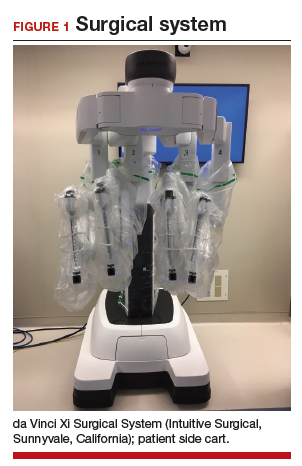

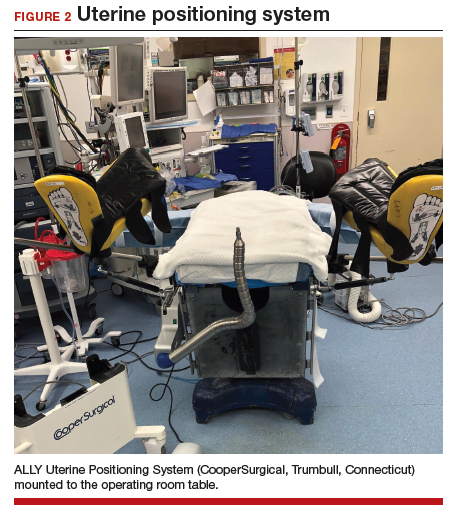

A uterine manipulator is a crucial tool used when performing LM.27 This instrument enables elevation of the uterus to allow for adequate visualization of the targeted myomas, traction-countertraction during enucleation, and strategic positioning during hysterotomy repair. We also use a bedside-mounted electric uterine positioning system that provides static orientation of the uterus by interfacing with the uterine manipulator, thereby obviating the need for a bedside assistant to provide that service (FIGURE 2).

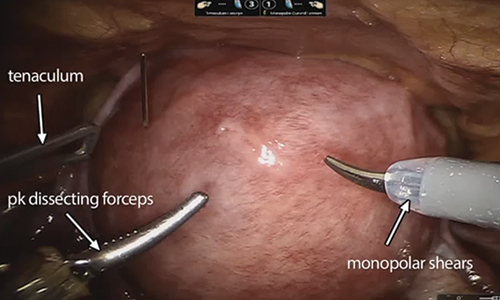

To minimize blood loss during the course of the myomectomy, we inject a dilute concentration of vasopressin (20 U in 50 mL of saline) via a 7-inch, 22-gauge spinal needle into the myometrium surrounding the targeted myomas (FIGURE 3). Additional methods for mitigating blood loss include the use of vascular clamps, clips, or ties (both permanent and temporary) on the bilateral uterine arteries; intravaginal prostaglandins; intravenous tranexamic acid; gelatin-thrombin matrices; and cell salvage systems.28

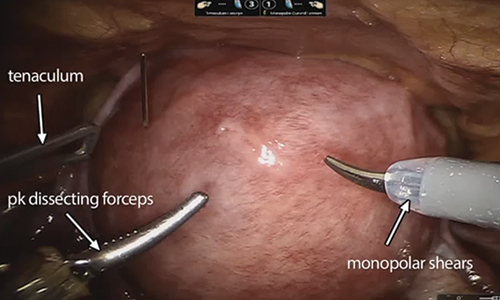

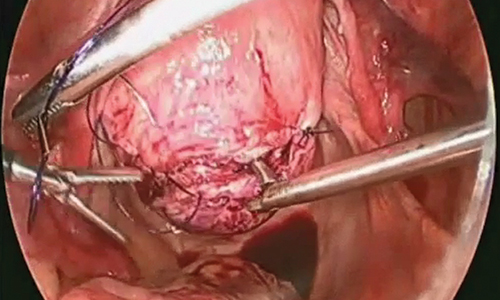

Once we observe adequate myometrial blanching from the vasopressin administration, we make a strategic hysterotomy incision (preferably transverse) to allow the surgeon to more ergonomically close the defect. We then identify the pseudocapsule so that the surgeon can circumferentially enucleate the myoma and dissect it from its fibrous attachments to the surrounding myometrium.

Continue to: The energy devices used to perform the hysterotomy...

The energy devices used to perform the hysterotomy and enucleation are selected largely based on surgeon preference, but various instruments can be used to accomplish these steps, including an ultrasonically activated scalpel or such electrosurgical instruments as monopolar scissors or hooks.

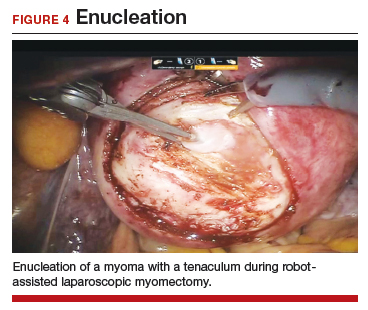

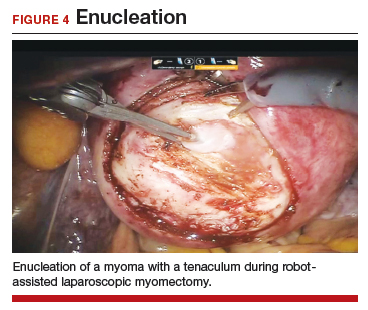

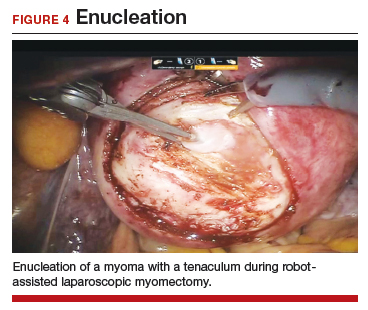

A reliable tenaculum is critical to the success of any enucleation, whether the approach is conventional LM or RALM, in order to provide adequate traction on the myoma (FIGURE 4). We try to minimize the number of hysterotomy incisions not only to reduce further blood loss, as the majority of bleeding ensues from the surrounding myometrium, but also to minimize compromise of myometrial integrity. Additionally, we take care to avoid entry into the endometrial cavity.

As we enucleate a myoma, we place it in either the anterior or posterior cul de sac. Most important, if we enucleate multiple myomas, we keep careful track of their number. We string the myomas together with suture until we extract them to ensure this.

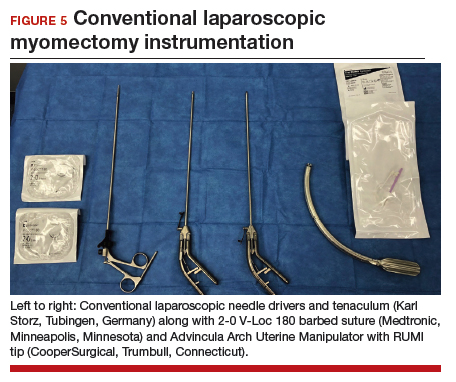

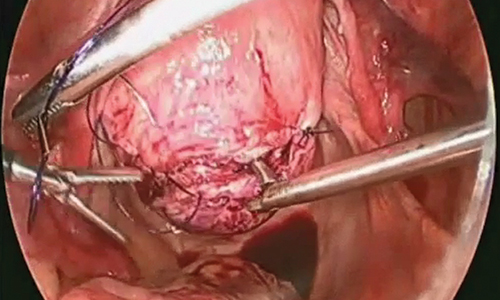

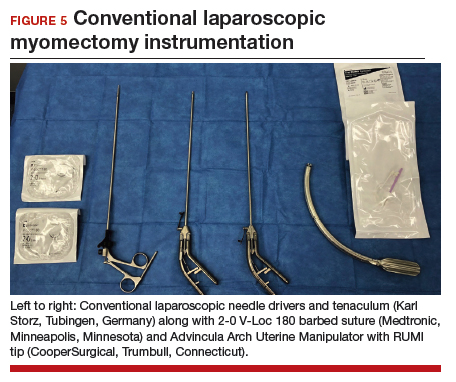

While hysterotomy closure can be performed with either barbed or nonbarbed sutures in a single- or a multi-layered fashion, we prefer to use a barbed suture.29,30 Just as enucleation requires appropriate instruments, suturing requires proper needle drivers (FIGURE 5). We advise judicious use of energy to minimize thermal effects and maintain the viability of the surrounding myometrium. Once we have sutured the myometrium closed, we place an adhesion barrier.

Although discussion of tissue extraction is beyond the scope of this Update, any surgeon embarking on either conventional LM or RALM must have a strategy for safe contained tissue extraction given the recent concerns over uncontained power morcellation.31,32

Surgical skill and careful patient selection are key to optimal outcomes

Patients seeking conservative surgical management of their uterine fibroids should be considered candidates for either a conventional LM or RALM. Both the scientific literature and technologic advances make these approaches viable options, especially when the surgeon’s skill is appropriate and the patient’s candidacy is adequately vetted. A well thought out surgical strategy from start to finish will ensure the chances for successful completion and optimized outcomes.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Matchar DB, Myers ER, Barber MW, et al. Management of uterine fibroids: summary. AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries. Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2001. AHRQ Publication No. 01-E051.

- Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

- Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet. 2001;357:293-298.

- Nash K, Feinglass J, Zei C, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy versus abdominal myomectomy: a comparative analysis of surgical outcomes and costs. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:435-440.

- Herrmann A, De Wilde RL. Laparoscopic myomectomy—the gold standard. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2014;3:31-38.

- Stoica RA, Bistriceanu I, Sima R, et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy. J Med Life. 2014;7:522-524.

- Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Uterine fibroid management: from the present to the future. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22:665-686.

- Holub Z. Laparoscopic myomectomy: indications and limits. Ceska Gynekol. 2007;72:64-68.

- Sinha R, Hegde A, Mahajan C, et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy: do size, number, and location of the myomas form limiting factors for laparoscopic myomectomy? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:292-300.

- Aksoy H, Aydin T, Ozdamar O, et al. Successful use of laparoscopic myomectomy to remove a giant uterine myoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:286.

- Damiani A, Melgrati L, Marziali M, et al. Laparoscopic myomectomy for very large myomas using an isobaric (gasless) technique. JSLS. 2005;9:434-438.

- Holzer A, Jirecek ST, Illievich UM, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy: a double-blind study to evaluate postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1480-1484.

- Mais V, Ajossa S, Guerriero S, et al. Laparoscopic versus abdominal myomectomy: a prospective, randomized trial to evaluate benefits in early outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:654-658.

- Jin C, Hu Y, Chen XC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open myomectomy—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:14-21.

- Pluchino N, Litta P, Freschi L, et al. Comparison of the initial surgical experience with robotic and laparoscopic myomectomy. Int J Med Robot. 2014;10:208-212.

- Parker WH, Iacampo K, Long T. Uterine rupture after laparoscopic removal of a pedunculated myoma. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:362-364.

- Advincula AP, Song A, Burke W, et al. Preliminary experience with robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:511-518.

- Advincula AP, Xu X, Goudeau S 4th, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy versus abdominal myomectomy: a comparison of short-term surgical outcomes and immediate costs. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:698-705.

- Nash K, Feinglass J, Zei C, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy versus abdominal myomectomy: a comparative analysis of surgical outcomes and costs. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:435-440.

- Mansour FW, Kives S, Urbach DR, et al. Robotically assisted laparoscopic myomectomy: a Canadian experience. J Obstet Gynaecol Canada. 2012;34:353-358.

- Sangha R, Eisenstein D, George A, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes for robotic assisted laparoscopic myomectomy compared to abdominal myomectomy (abstract 373). J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(suppl):S90-S108.

- Pundir J, Pundir V, Walavalkar R, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic vs abdominal and laparoscopic myomectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013; 20:335–345.

- Pitter MC, Srouji SS, Gargiulo AR, et al. Fertility and symptom relief following robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2015. doi:10.1155/2015/967568.

- Pitter MC, Gargiulo AR, Bonaventura LM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes following robot-assisted myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2013; 28:99-108.

- Cela V, Freschi L, Simi G, et al. Fertility and endocrine outcome after robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy (RALM). Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29:79-82.

- Kang SY, Jeung IC, Chung YJ, et al. Robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy for deep intramural myomas. Int J Med Robot. 2017;13. doi:10.1002/rcs.1742.

- van den Haak L, Alleblas C, Nieboer TE, et al. Efficacy and safety of uterine manipulators in laparoscopic surgery: a review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;292:1003-1011.

- Hickman LC, Kotlyar A, Shue S, et al. Hemostatic techniques for myomectomy: an evidence-based approach. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:497-504.

- Tulandi T, Einarsson JI. The use of barbed suture for laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:210-216.

- Alessandri F, Remorgida V, Venturini PL, et al. Unidirectional barbed suture versus continuous suture with intracorporeal knots in laparoscopic myomectomy: a randomized study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17:725-729.

- AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL practice report: morcellation during uterine tissue extraction. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:517-530.

- Meurs EA, Brito LG, Ajao MO, et al. Comparison of morcellation techniques at the time of laparoscopic hysterectomy and myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:843-849.

Uterine fibroids are the most common solid pelvic tumor in women and a leading indication for hysterectomy in the United States.1 As a result, they represent significant morbidity for many women and are a major public health problem. By age 50, 70% of white women and 80% of black women have fibroids.2

Although fibroids are sometimes asymptomatic, the symptoms most commonly reported are abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) with resultant anemia and bulk/pressure symptoms. Uterine fibroids also are associated with reproductive dysfunction, such as recurrent pregnancy loss, and even infertility.3

The clinical diagnosis of uterine fibroids is made based on a combination of physical examination and imaging studies, including pelvic ultrasonography, saline infusion sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When medical management, such as combination oral contraceptive pills, fails in patients with AUB and/or bulk predominant symptoms or patients present with compromised fertility, the only option for conservative surgical management is a myomectomy.4

The route of myomectomy—hysteroscopy, laparotomy, conventional laparoscopic myomectomy (LM), or robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy (RALM)—depends on the size, number, location, and consistency of the uterine fibroids and, to a certain extent, the indication for the myomectomy. In some cases, multiple routes must be used to achieve optimal results, and sometimes these procedures have to be staged. In this literature review and technical summary, we focus on conventional LM and RALM approaches.

Literature review: In the right hands, LM and RALM have clear benefits

In the past, laparotomy was the surgical route of choice for fibroid removal. This surgery was associated with a long hospital stay, a high rate of blood transfusions, postoperative pain, and a lengthy recovery period. As minimally invasive surgery gained popularity, conventional LM became more commonly performed and was accepted by many as the gold standard approach for myomectomy.5

LM has considerable advantages over laparotomy

Compared with the traditional, more invasive route, the conventional LM approach has many benefits. These include less blood loss, decreased postoperative pain, shorter recovery time, shorter hospitalization stay, and decreased perioperative complications.6 LM should be considered the first-line approach unless the size of an intramural myoma exceeds 10 to 12 cm or multiple myomas (consensus, approximately 4 or more) are present and necessitate several incisions according to their varying locations within the uterus.7,8 While this is a recommendation, reports have been published on the successful laparoscopic approach to myomas larger than 20 cm, demonstrating that a skilled, experienced surgeon can perform this procedure safely.9-11