User login

Older age, r/r disease in lymphoma patients tied to increased COVID-19 death rate

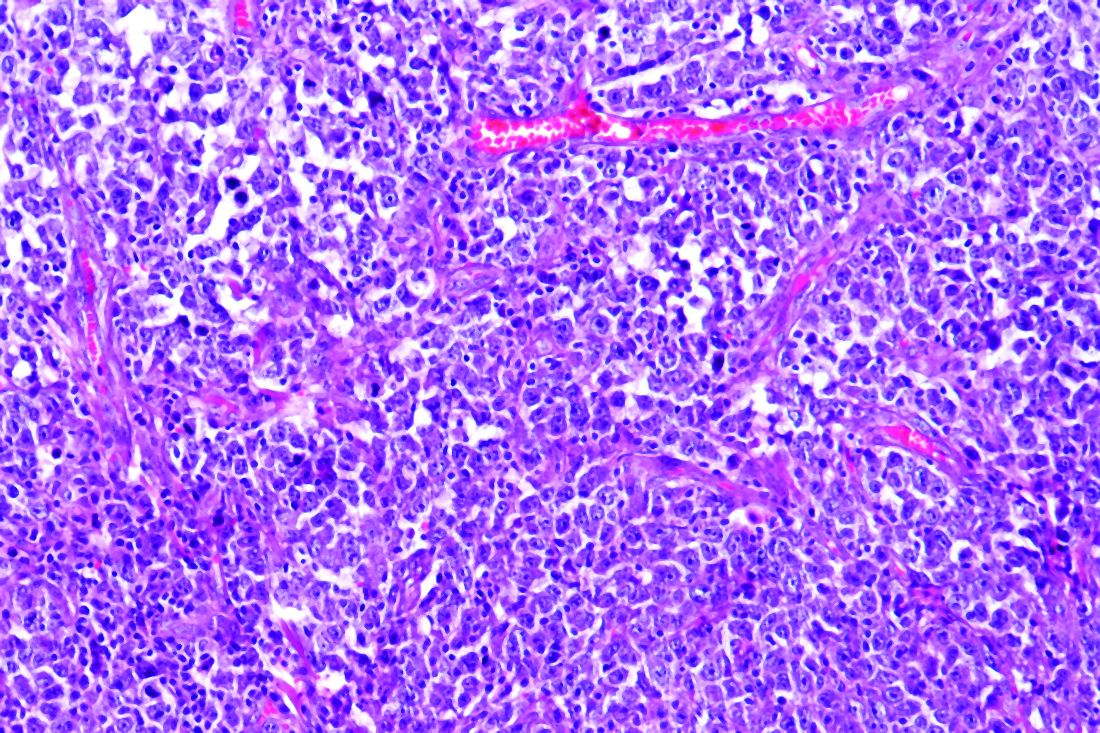

Patients with B-cell lymphoma are immunocompromised because of the disease and its treatments. This presents the question of their outcomes upon infection with SARS-CoV-2. Researchers assessed the characteristics of patients with lymphoma hospitalized for COVID-19 and analyzed determinants of mortality in a retrospective database study. The investigators looked at data from adult patients with lymphoma who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020 in three French regions.

Older age and relapsed/refractory (r/r) disease in B-cell lymphoma patients were both found to be independent risk factors of increased death rate from COVID-19, according to the online report in EClinicalMedicine, published by The Lancet.

These results encourage “the application of standard Covid-19 treatment, including intubation, for lymphoma patients with Covid-19 lymphoma diagnosis, under first- or second-line chemotherapy, or in remission,” according to Sylvain Lamure, MD, of Montellier (France) University, and colleagues.

The study examined a series of 89 consecutive patients from three French regions who had lymphoma and were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020. The population was homogeneous; most patients were diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and had been treated for their lymphoma within 1 year.

Promising results for many

There were a significant associations between 30-day mortality and increasing age (over age 70 years) and r/r lymphoma. However, in the absence of those factors, mortality of the lymphoma patients with COVID-19 was comparable with that of the reference French COVID-19 population. In addition, there was no significant impact of active lymphoma treatment that had been given within 1 year, except for those patients who received bendamustine, which was associated with greater mortality, according to the researchers.

With a median follow-up of 33 days from admission, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 30-day overall survival was 71% (95% confidence interval, 62%-81%). According to histological type of the lymphoma, 30-day overall survival rates were 80% (95% CI, 45%-100%) for Hodgkin lymphoma, 71% (95% CI, 61%-82%) for B-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and 71% (95% CI, 38%-100%) for T-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

The main factors associated with mortality were age 70 years and older (hazard ratio, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.73-8.25; P = .0009), hypertension (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.06-4.59; P = .03), previous cancer (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.90-4.92; P = .08), use of bendamustine within 12 months before admission to hospital (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.31-7.11; P = .01), and r/r lymphoma (HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.20-5.72; P = .02).

Overall, the Kaplan-Meier estimates of 30-day overall survival were 61% for patients with r/r lymphoma, 52% in patients age 70 years with non–r/r lymphoma, and 88% for patients younger than 70 years with non–r/r, which was comparable with general population survival data among French populations, according to the researchers.

“Longer term clinical follow-up and biological monitoring of immune responses is warranted to explore the impact of lymphoma and its treatment on the immunity and prolonged outcome of Covid-19 patients,” they concluded.

The study was unsponsored. Several of the authors reported financial relationships with a number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lamure S et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100549.

Patients with B-cell lymphoma are immunocompromised because of the disease and its treatments. This presents the question of their outcomes upon infection with SARS-CoV-2. Researchers assessed the characteristics of patients with lymphoma hospitalized for COVID-19 and analyzed determinants of mortality in a retrospective database study. The investigators looked at data from adult patients with lymphoma who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020 in three French regions.

Older age and relapsed/refractory (r/r) disease in B-cell lymphoma patients were both found to be independent risk factors of increased death rate from COVID-19, according to the online report in EClinicalMedicine, published by The Lancet.

These results encourage “the application of standard Covid-19 treatment, including intubation, for lymphoma patients with Covid-19 lymphoma diagnosis, under first- or second-line chemotherapy, or in remission,” according to Sylvain Lamure, MD, of Montellier (France) University, and colleagues.

The study examined a series of 89 consecutive patients from three French regions who had lymphoma and were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020. The population was homogeneous; most patients were diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and had been treated for their lymphoma within 1 year.

Promising results for many

There were a significant associations between 30-day mortality and increasing age (over age 70 years) and r/r lymphoma. However, in the absence of those factors, mortality of the lymphoma patients with COVID-19 was comparable with that of the reference French COVID-19 population. In addition, there was no significant impact of active lymphoma treatment that had been given within 1 year, except for those patients who received bendamustine, which was associated with greater mortality, according to the researchers.

With a median follow-up of 33 days from admission, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 30-day overall survival was 71% (95% confidence interval, 62%-81%). According to histological type of the lymphoma, 30-day overall survival rates were 80% (95% CI, 45%-100%) for Hodgkin lymphoma, 71% (95% CI, 61%-82%) for B-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and 71% (95% CI, 38%-100%) for T-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

The main factors associated with mortality were age 70 years and older (hazard ratio, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.73-8.25; P = .0009), hypertension (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.06-4.59; P = .03), previous cancer (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.90-4.92; P = .08), use of bendamustine within 12 months before admission to hospital (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.31-7.11; P = .01), and r/r lymphoma (HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.20-5.72; P = .02).

Overall, the Kaplan-Meier estimates of 30-day overall survival were 61% for patients with r/r lymphoma, 52% in patients age 70 years with non–r/r lymphoma, and 88% for patients younger than 70 years with non–r/r, which was comparable with general population survival data among French populations, according to the researchers.

“Longer term clinical follow-up and biological monitoring of immune responses is warranted to explore the impact of lymphoma and its treatment on the immunity and prolonged outcome of Covid-19 patients,” they concluded.

The study was unsponsored. Several of the authors reported financial relationships with a number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lamure S et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100549.

Patients with B-cell lymphoma are immunocompromised because of the disease and its treatments. This presents the question of their outcomes upon infection with SARS-CoV-2. Researchers assessed the characteristics of patients with lymphoma hospitalized for COVID-19 and analyzed determinants of mortality in a retrospective database study. The investigators looked at data from adult patients with lymphoma who were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020 in three French regions.

Older age and relapsed/refractory (r/r) disease in B-cell lymphoma patients were both found to be independent risk factors of increased death rate from COVID-19, according to the online report in EClinicalMedicine, published by The Lancet.

These results encourage “the application of standard Covid-19 treatment, including intubation, for lymphoma patients with Covid-19 lymphoma diagnosis, under first- or second-line chemotherapy, or in remission,” according to Sylvain Lamure, MD, of Montellier (France) University, and colleagues.

The study examined a series of 89 consecutive patients from three French regions who had lymphoma and were hospitalized for COVID-19 in March and April 2020. The population was homogeneous; most patients were diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and had been treated for their lymphoma within 1 year.

Promising results for many

There were a significant associations between 30-day mortality and increasing age (over age 70 years) and r/r lymphoma. However, in the absence of those factors, mortality of the lymphoma patients with COVID-19 was comparable with that of the reference French COVID-19 population. In addition, there was no significant impact of active lymphoma treatment that had been given within 1 year, except for those patients who received bendamustine, which was associated with greater mortality, according to the researchers.

With a median follow-up of 33 days from admission, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of 30-day overall survival was 71% (95% confidence interval, 62%-81%). According to histological type of the lymphoma, 30-day overall survival rates were 80% (95% CI, 45%-100%) for Hodgkin lymphoma, 71% (95% CI, 61%-82%) for B-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, and 71% (95% CI, 38%-100%) for T-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

The main factors associated with mortality were age 70 years and older (hazard ratio, 3.78; 95% CI, 1.73-8.25; P = .0009), hypertension (HR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.06-4.59; P = .03), previous cancer (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 0.90-4.92; P = .08), use of bendamustine within 12 months before admission to hospital (HR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.31-7.11; P = .01), and r/r lymphoma (HR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.20-5.72; P = .02).

Overall, the Kaplan-Meier estimates of 30-day overall survival were 61% for patients with r/r lymphoma, 52% in patients age 70 years with non–r/r lymphoma, and 88% for patients younger than 70 years with non–r/r, which was comparable with general population survival data among French populations, according to the researchers.

“Longer term clinical follow-up and biological monitoring of immune responses is warranted to explore the impact of lymphoma and its treatment on the immunity and prolonged outcome of Covid-19 patients,” they concluded.

The study was unsponsored. Several of the authors reported financial relationships with a number of biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Lamure S et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100549.

FROM ECLINICALMEDICINE

Link between vitamin D and ICU outcomes unclear

We can “stop putting money on vitamin D” to help patients who require critical care, said Todd Rice, MD, FCCP.

“Results from vitamin D trials have not been uniformly one way, but they have been pretty uniformly disappointing,” Dr. Rice, from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Low levels of vitamin D in critically ill COVID-19 patients have been reported in numerous recent studies, and researchers are looking for ways to boost those levels and improve outcomes.

We are seeing “the exact same story” in the critically ill COVID-19 population as we see in the general ICU population, said Dr. Rice. “The whole scenario is repeating itself. I’m pessimistic.”

Still, vitamin D levels can be elevated so, in theory, “the concept makes sense,” he said. There is evidence that, “when given enterally, the levels rise nicely” and vitamin D is absorbed reasonably well.” But is that enough?

When patients are admitted to the ICU, some biomarkers in the body are too high and others are too low. Vitamin D is often too low. So far, though, “supplementing vitamin D in the ICU has not significantly improved outcomes,” said Dr. Rice.

In the Vitamin D to Improve Outcomes by Leveraging Early Treatment (VIOLET) trial, Dr. Rice and colleagues found no statistical benefit when a 540,000 IU boost of vitamin D was administered to 2,624 critically ill patients, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

“Early administration of high-dose enteral vitamin D3 did not provide an advantage over placebo with respect to 90-day mortality or other nonfatal outcomes among critically ill, vitamin D–deficient patients,” the researchers write in their recent report.

In fact, VIOLET ended before enrollment had reached the planned 3,000-patient cohort because the statistical analysis clearly did not show benefit. Those enrolled were in the ICU because of, among other things, pneumonia, sepsis, the need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressors, and risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome.

“It doesn’t look like vitamin D is going to be the answer to our critical care problems,” Dr. Rice said in an interview.

Maintenance dose needed?

One theory suggests that VIOLET might have failed because a maintenance dose is needed after the initial boost of vitamin D.

In the ongoing VITDALIZE trial, critically ill patients with severe vitamin D deficiency (12 ng/mL or less at admission) receive an initial 540,000-IU dose followed by 4,000 IU per day.

The highly anticipated VITDALIZE results are expected in the middle of next year, Dr. Rice reported, so “let’s wait to see.”

“Vitamin D may not have an acute effect,” he theorized. “We can raise your levels, but that doesn’t give you all the benefits of having a sufficient level for a long period of time.”

Another theory suggests that a low level of vitamin D is simply a signal of the severity of disease, not a direct influence on disease pathology.

Some observational data have shown an association between low levels of vitamin D and outcomes in COVID-19 patients (Nutrients. 2020 May 9;12[5]:1359; medRxiv 2020 Apr 24. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.24.20075838; JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[9]:e2019722; FEBS J. 2020 Jul 23;10.1111/febs.15495; Clin Endocrinol [Oxf]. 2020 Jul 3;10.1111/cen.14276), but some have shown no association (medRxiv. 2020 Jun 26. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.26.20140921; J Public Health [Oxf]. 2020 Aug 18;42[3]:451-60).

Dr. Rice conducted a search of Clinicaltrials.gov immediately before his presentation on Sunday, and found 41 ongoing interventional studies – “not observational studies” – looking at COVID-19 and vitamin D.

“They’re recruiting, they’re enrolling; hopefully we’ll have data soon,” he said.

Researchers have checked a lot of boxes with a resounding yes on the vitamin D question, so there’s reason to think an association does exist for ICU patients, whether or not they have COVID-19.

“Is there a theoretical benefit of vitamin D in the ICU?” Dr. Rice asked. “Yes. Is vitamin D deficient in patients in the ICU? Yes. Is that deficiency associated with poor outcomes? Yes. Can it be replaced safely? Yes.”

However, “we’re not really sure that it improves outcomes,” he said.

A chronic issue?

“Do you think it’s really an issue of the patients being critically ill with vitamin D,” or is it “a chronic issue of having low vitamin D?” asked session moderator Antine Stenbit, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We don’t know for sure,” Dr. Rice said. Vitamin D might not have a lot of acute effects; it might have effects that are chronic, that work with levels over a period of time, he explained.

“It’s not clear we can correct that with a single dose or with a few days of giving a level that is adequate,” he acknowledged.

Dr. Rice is an investigator in the PETAL network. Dr. Stenbit disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

We can “stop putting money on vitamin D” to help patients who require critical care, said Todd Rice, MD, FCCP.

“Results from vitamin D trials have not been uniformly one way, but they have been pretty uniformly disappointing,” Dr. Rice, from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Low levels of vitamin D in critically ill COVID-19 patients have been reported in numerous recent studies, and researchers are looking for ways to boost those levels and improve outcomes.

We are seeing “the exact same story” in the critically ill COVID-19 population as we see in the general ICU population, said Dr. Rice. “The whole scenario is repeating itself. I’m pessimistic.”

Still, vitamin D levels can be elevated so, in theory, “the concept makes sense,” he said. There is evidence that, “when given enterally, the levels rise nicely” and vitamin D is absorbed reasonably well.” But is that enough?

When patients are admitted to the ICU, some biomarkers in the body are too high and others are too low. Vitamin D is often too low. So far, though, “supplementing vitamin D in the ICU has not significantly improved outcomes,” said Dr. Rice.

In the Vitamin D to Improve Outcomes by Leveraging Early Treatment (VIOLET) trial, Dr. Rice and colleagues found no statistical benefit when a 540,000 IU boost of vitamin D was administered to 2,624 critically ill patients, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

“Early administration of high-dose enteral vitamin D3 did not provide an advantage over placebo with respect to 90-day mortality or other nonfatal outcomes among critically ill, vitamin D–deficient patients,” the researchers write in their recent report.

In fact, VIOLET ended before enrollment had reached the planned 3,000-patient cohort because the statistical analysis clearly did not show benefit. Those enrolled were in the ICU because of, among other things, pneumonia, sepsis, the need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressors, and risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome.

“It doesn’t look like vitamin D is going to be the answer to our critical care problems,” Dr. Rice said in an interview.

Maintenance dose needed?

One theory suggests that VIOLET might have failed because a maintenance dose is needed after the initial boost of vitamin D.

In the ongoing VITDALIZE trial, critically ill patients with severe vitamin D deficiency (12 ng/mL or less at admission) receive an initial 540,000-IU dose followed by 4,000 IU per day.

The highly anticipated VITDALIZE results are expected in the middle of next year, Dr. Rice reported, so “let’s wait to see.”

“Vitamin D may not have an acute effect,” he theorized. “We can raise your levels, but that doesn’t give you all the benefits of having a sufficient level for a long period of time.”

Another theory suggests that a low level of vitamin D is simply a signal of the severity of disease, not a direct influence on disease pathology.

Some observational data have shown an association between low levels of vitamin D and outcomes in COVID-19 patients (Nutrients. 2020 May 9;12[5]:1359; medRxiv 2020 Apr 24. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.24.20075838; JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[9]:e2019722; FEBS J. 2020 Jul 23;10.1111/febs.15495; Clin Endocrinol [Oxf]. 2020 Jul 3;10.1111/cen.14276), but some have shown no association (medRxiv. 2020 Jun 26. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.26.20140921; J Public Health [Oxf]. 2020 Aug 18;42[3]:451-60).

Dr. Rice conducted a search of Clinicaltrials.gov immediately before his presentation on Sunday, and found 41 ongoing interventional studies – “not observational studies” – looking at COVID-19 and vitamin D.

“They’re recruiting, they’re enrolling; hopefully we’ll have data soon,” he said.

Researchers have checked a lot of boxes with a resounding yes on the vitamin D question, so there’s reason to think an association does exist for ICU patients, whether or not they have COVID-19.

“Is there a theoretical benefit of vitamin D in the ICU?” Dr. Rice asked. “Yes. Is vitamin D deficient in patients in the ICU? Yes. Is that deficiency associated with poor outcomes? Yes. Can it be replaced safely? Yes.”

However, “we’re not really sure that it improves outcomes,” he said.

A chronic issue?

“Do you think it’s really an issue of the patients being critically ill with vitamin D,” or is it “a chronic issue of having low vitamin D?” asked session moderator Antine Stenbit, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We don’t know for sure,” Dr. Rice said. Vitamin D might not have a lot of acute effects; it might have effects that are chronic, that work with levels over a period of time, he explained.

“It’s not clear we can correct that with a single dose or with a few days of giving a level that is adequate,” he acknowledged.

Dr. Rice is an investigator in the PETAL network. Dr. Stenbit disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

We can “stop putting money on vitamin D” to help patients who require critical care, said Todd Rice, MD, FCCP.

“Results from vitamin D trials have not been uniformly one way, but they have been pretty uniformly disappointing,” Dr. Rice, from Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Low levels of vitamin D in critically ill COVID-19 patients have been reported in numerous recent studies, and researchers are looking for ways to boost those levels and improve outcomes.

We are seeing “the exact same story” in the critically ill COVID-19 population as we see in the general ICU population, said Dr. Rice. “The whole scenario is repeating itself. I’m pessimistic.”

Still, vitamin D levels can be elevated so, in theory, “the concept makes sense,” he said. There is evidence that, “when given enterally, the levels rise nicely” and vitamin D is absorbed reasonably well.” But is that enough?

When patients are admitted to the ICU, some biomarkers in the body are too high and others are too low. Vitamin D is often too low. So far, though, “supplementing vitamin D in the ICU has not significantly improved outcomes,” said Dr. Rice.

In the Vitamin D to Improve Outcomes by Leveraging Early Treatment (VIOLET) trial, Dr. Rice and colleagues found no statistical benefit when a 540,000 IU boost of vitamin D was administered to 2,624 critically ill patients, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

“Early administration of high-dose enteral vitamin D3 did not provide an advantage over placebo with respect to 90-day mortality or other nonfatal outcomes among critically ill, vitamin D–deficient patients,” the researchers write in their recent report.

In fact, VIOLET ended before enrollment had reached the planned 3,000-patient cohort because the statistical analysis clearly did not show benefit. Those enrolled were in the ICU because of, among other things, pneumonia, sepsis, the need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressors, and risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome.

“It doesn’t look like vitamin D is going to be the answer to our critical care problems,” Dr. Rice said in an interview.

Maintenance dose needed?

One theory suggests that VIOLET might have failed because a maintenance dose is needed after the initial boost of vitamin D.

In the ongoing VITDALIZE trial, critically ill patients with severe vitamin D deficiency (12 ng/mL or less at admission) receive an initial 540,000-IU dose followed by 4,000 IU per day.

The highly anticipated VITDALIZE results are expected in the middle of next year, Dr. Rice reported, so “let’s wait to see.”

“Vitamin D may not have an acute effect,” he theorized. “We can raise your levels, but that doesn’t give you all the benefits of having a sufficient level for a long period of time.”

Another theory suggests that a low level of vitamin D is simply a signal of the severity of disease, not a direct influence on disease pathology.

Some observational data have shown an association between low levels of vitamin D and outcomes in COVID-19 patients (Nutrients. 2020 May 9;12[5]:1359; medRxiv 2020 Apr 24. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.24.20075838; JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3[9]:e2019722; FEBS J. 2020 Jul 23;10.1111/febs.15495; Clin Endocrinol [Oxf]. 2020 Jul 3;10.1111/cen.14276), but some have shown no association (medRxiv. 2020 Jun 26. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.26.20140921; J Public Health [Oxf]. 2020 Aug 18;42[3]:451-60).

Dr. Rice conducted a search of Clinicaltrials.gov immediately before his presentation on Sunday, and found 41 ongoing interventional studies – “not observational studies” – looking at COVID-19 and vitamin D.

“They’re recruiting, they’re enrolling; hopefully we’ll have data soon,” he said.

Researchers have checked a lot of boxes with a resounding yes on the vitamin D question, so there’s reason to think an association does exist for ICU patients, whether or not they have COVID-19.

“Is there a theoretical benefit of vitamin D in the ICU?” Dr. Rice asked. “Yes. Is vitamin D deficient in patients in the ICU? Yes. Is that deficiency associated with poor outcomes? Yes. Can it be replaced safely? Yes.”

However, “we’re not really sure that it improves outcomes,” he said.

A chronic issue?

“Do you think it’s really an issue of the patients being critically ill with vitamin D,” or is it “a chronic issue of having low vitamin D?” asked session moderator Antine Stenbit, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Diego.

“We don’t know for sure,” Dr. Rice said. Vitamin D might not have a lot of acute effects; it might have effects that are chronic, that work with levels over a period of time, he explained.

“It’s not clear we can correct that with a single dose or with a few days of giving a level that is adequate,” he acknowledged.

Dr. Rice is an investigator in the PETAL network. Dr. Stenbit disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CHEST 2020

Sleepless nights, hair loss, and cracked teeth: Pandemic stress takes its toll

In late March, shortly after New York state closed nonessential businesses and asked people to stay home, Ashley Laderer began waking each morning with a throbbing headache.

“The pressure was so intense it felt like my head was going to explode,” recalled the 27-year-old freelance writer from Long Island.

She tried spending less time on the computer and taking over-the-counter pain medication, but the pounding kept breaking through – a constant drumbeat to accompany her equally incessant worries about COVID-19.

“Every day I lived in fear that I was going to get it and I was going to infect my whole family,” she said.

After a month and a half, Ms. Laderer decided to visit a neurologist, who ordered an MRI. But the doctor found no physical cause. The scan was clear.

Then he asked: “Are you under a lot of stress?”

excruciating headaches, episodes of hair loss, upset stomach for weeks on end, sudden outbreaks of shingles, and flare-ups of autoimmune disorders. The disparate symptoms, often in otherwise-healthy individuals, have puzzled doctors and patients alike, sometimes resulting in a series of visits to specialists with few answers. But it turns out there’s a common thread among many of these conditions, one that has been months in the making: chronic stress.

Although people often underestimate the influence of the mind on the body, a growing catalog of research shows that high levels of stress over an extended time can drastically alter physical function and affect nearly every organ system.

Now, at least 8 months into the pandemic, alongside a divisive election cycle and racial unrest, those effects are showing up in a variety of symptoms.

“The mental health component of COVID is starting to come like a tsunami,” said Jennifer Love, MD, a California-based psychiatrist and coauthor of an upcoming book on how to heal from chronic stress.

Nationwide, surveys have found increasing rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts during the pandemic. But many medical experts said it’s too soon to measure the related physical symptoms, since they generally appear months after the stress begins.

Still, some early research, such as a small Chinese study and an online survey of more than 500 people in Turkey, points to an uptick.

In the United States, data from FAIR Health, a nonprofit database that provides cost information to the health industry and consumers, showed slight to moderate increases in the percentage of medical claims related to conditions triggered or exacerbated by stress, like multiple sclerosis and shingles. The portion of claims for the autoimmune disease lupus, for example, showed one of the biggest increases – 12% this year – compared with the same period last year (January to August).

Express Scripts, a major pharmacy benefit manager, reported that prescriptions for anti-insomnia medications increased 15% early in the pandemic.

Perhaps the strongest indicator comes from doctors reporting a growing number of patients with physical symptoms for which they can’t determine a cause.

Shilpi Khetarpal, MD, a dermatologist at the Cleveland Clinic, used to see about five patients a week with stress-related hair loss. Since mid-June, that number has jumped to 20 or 25. Mostly women, ages 20-80, are reporting hair coming out in fistfuls, Dr. Khetarpal said.

In Houston, at least a dozen patients have told fertility specialist Rashmi Kudesia, MD, they’re having irregular menstrual cycles, changes in cervical discharge and breast tenderness, despite normal hormone levels.

Stress is also the culprit dentists are pointing to for the rapid increase in patients with teeth grinding, teeth fractures, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

“We, as humans, like to have the idea that we are in control of our minds and that stress isn’t a big deal,” Dr. Love said. “But it’s simply not true.”

How mental stress becomes physical

Stress causes physical changes in the body that can affect nearly every organ system.

Although symptoms of chronic stress are often dismissed as being in one’s head, the pain is very real, said Kate Harkness, PhD, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont.

When the body feels unsafe – whether it’s a physical threat of attack or a psychological fear of losing a job or catching a disease – the brain signals adrenal glands to pump stress hormones. Adrenaline and cortisol flood the body, activating the fight-or-flight response. They also disrupt bodily functions that aren’t necessary for immediate survival, like digestion and reproduction.

When the danger is over, the hormones return to normal levels. But during times of chronic stress, like a pandemic, the body keeps pumping out stress hormones until it tires itself out. This leads to increased inflammation throughout the body and brain, and a poorly functioning immune system.

Studies link chronic stress to heart disease, muscle tension, gastrointestinal issues and even physical shrinking of the hippocampus, an area of the brain associated with memory and learning. As the immune system acts up, some people can even develop new allergic reactions, Dr. Harkness said.

The good news is that many of these symptoms are reversible. But it’s important to recognize them early, especially when it comes to the brain, said Barbara Sahakian, FBA, FMedSci, a professor of clinical neuropsychology at the University of Cambridge (England).

“The brain is plastic, so we can to some extent modify it,” Dr. Sahakian said. “But we don’t know if there’s a cliff beyond which you can’t reverse a change. So the sooner you catch something, the better.”

The day-to-day impact

In some ways, mental health awareness has increased during the pandemic. TV shows are flush with ads for therapy and meditation apps, like Talkspace and Calm, and companies are announcing mental health days off for staff. But those spurts of attention fail to reveal the full impact of poor mental health on people’s daily lives.

For Alex Kostka, pandemic-related stress has brought on mood swings, nightmares, and jaw pain.

He’d been working at a Whole Foods coffee bar in New York City for only about a month before the pandemic hit, suddenly anointing him an essential worker. As deaths in the city soared, Mr. Kostka continued riding the subway to work, interacting with coworkers in the store and working longer hours for just a $2-per-hour wage increase. (Months later, he’d get a $500 bonus.) It left the 28-year-old feeling constantly unsafe and helpless.

“It was hard not to break down on the subway the minute I got on it,” Mr. Kostka said.

Soon he began waking in the middle of the night with pain from clenching his jaw so tightly. Often his teeth grinding and chomping were loud enough to wake his girlfriend.

Mr. Kostka tried Talkspace, but found texting about his troubles felt impersonal. By the end of the summer, he decided to start using the seven free counseling sessions offered by his employer. That’s helped, he said. But as the sessions run out, he worries the symptoms might return if he’s unable to find a new therapist covered by his insurance.

“Eventually, I will be able to leave this behind me, but it will take time,” Mr. Kostka said. “I’m still very much a work in progress.”

How to mitigate chronic stress

When it comes to chronic stress, seeing a doctor for stomach pain, headaches, or skin rashes may address those physical symptoms. But the root cause is mental, medical experts said.

That means the solution will often involve stress-management techniques. And there’s plenty we can do to feel better:

- Exercise. Even low- to moderate-intensity physical activity can help counteract stress-induced inflammation in the body. It can also increase neuronal connections in the brain.

- Meditation and mindfulness. Research shows this can lead to positive, structural, and functional changes in the brain.

- Fostering social connections. Talking to family and friends, even virtually, or staring into a pet’s eyes can release a hormone that may counteract inflammation.

- Learning something new. Whether it’s a formal class or taking up a casual hobby, learning supports brain plasticity, the ability to change and adapt as a result of experience, which can be protective against depression and other mental illness.

“We shouldn’t think of this stressful situation as a negative sentence for the brain,” said Dr. Harkness. “Because stress changes the brain, that means positive stuff can change the brain, too. And there is plenty we can do to help ourselves feel better in the face of adversity.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

In late March, shortly after New York state closed nonessential businesses and asked people to stay home, Ashley Laderer began waking each morning with a throbbing headache.

“The pressure was so intense it felt like my head was going to explode,” recalled the 27-year-old freelance writer from Long Island.

She tried spending less time on the computer and taking over-the-counter pain medication, but the pounding kept breaking through – a constant drumbeat to accompany her equally incessant worries about COVID-19.

“Every day I lived in fear that I was going to get it and I was going to infect my whole family,” she said.

After a month and a half, Ms. Laderer decided to visit a neurologist, who ordered an MRI. But the doctor found no physical cause. The scan was clear.

Then he asked: “Are you under a lot of stress?”

excruciating headaches, episodes of hair loss, upset stomach for weeks on end, sudden outbreaks of shingles, and flare-ups of autoimmune disorders. The disparate symptoms, often in otherwise-healthy individuals, have puzzled doctors and patients alike, sometimes resulting in a series of visits to specialists with few answers. But it turns out there’s a common thread among many of these conditions, one that has been months in the making: chronic stress.

Although people often underestimate the influence of the mind on the body, a growing catalog of research shows that high levels of stress over an extended time can drastically alter physical function and affect nearly every organ system.

Now, at least 8 months into the pandemic, alongside a divisive election cycle and racial unrest, those effects are showing up in a variety of symptoms.

“The mental health component of COVID is starting to come like a tsunami,” said Jennifer Love, MD, a California-based psychiatrist and coauthor of an upcoming book on how to heal from chronic stress.

Nationwide, surveys have found increasing rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts during the pandemic. But many medical experts said it’s too soon to measure the related physical symptoms, since they generally appear months after the stress begins.

Still, some early research, such as a small Chinese study and an online survey of more than 500 people in Turkey, points to an uptick.

In the United States, data from FAIR Health, a nonprofit database that provides cost information to the health industry and consumers, showed slight to moderate increases in the percentage of medical claims related to conditions triggered or exacerbated by stress, like multiple sclerosis and shingles. The portion of claims for the autoimmune disease lupus, for example, showed one of the biggest increases – 12% this year – compared with the same period last year (January to August).

Express Scripts, a major pharmacy benefit manager, reported that prescriptions for anti-insomnia medications increased 15% early in the pandemic.

Perhaps the strongest indicator comes from doctors reporting a growing number of patients with physical symptoms for which they can’t determine a cause.

Shilpi Khetarpal, MD, a dermatologist at the Cleveland Clinic, used to see about five patients a week with stress-related hair loss. Since mid-June, that number has jumped to 20 or 25. Mostly women, ages 20-80, are reporting hair coming out in fistfuls, Dr. Khetarpal said.

In Houston, at least a dozen patients have told fertility specialist Rashmi Kudesia, MD, they’re having irregular menstrual cycles, changes in cervical discharge and breast tenderness, despite normal hormone levels.

Stress is also the culprit dentists are pointing to for the rapid increase in patients with teeth grinding, teeth fractures, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

“We, as humans, like to have the idea that we are in control of our minds and that stress isn’t a big deal,” Dr. Love said. “But it’s simply not true.”

How mental stress becomes physical

Stress causes physical changes in the body that can affect nearly every organ system.

Although symptoms of chronic stress are often dismissed as being in one’s head, the pain is very real, said Kate Harkness, PhD, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont.

When the body feels unsafe – whether it’s a physical threat of attack or a psychological fear of losing a job or catching a disease – the brain signals adrenal glands to pump stress hormones. Adrenaline and cortisol flood the body, activating the fight-or-flight response. They also disrupt bodily functions that aren’t necessary for immediate survival, like digestion and reproduction.

When the danger is over, the hormones return to normal levels. But during times of chronic stress, like a pandemic, the body keeps pumping out stress hormones until it tires itself out. This leads to increased inflammation throughout the body and brain, and a poorly functioning immune system.

Studies link chronic stress to heart disease, muscle tension, gastrointestinal issues and even physical shrinking of the hippocampus, an area of the brain associated with memory and learning. As the immune system acts up, some people can even develop new allergic reactions, Dr. Harkness said.

The good news is that many of these symptoms are reversible. But it’s important to recognize them early, especially when it comes to the brain, said Barbara Sahakian, FBA, FMedSci, a professor of clinical neuropsychology at the University of Cambridge (England).

“The brain is plastic, so we can to some extent modify it,” Dr. Sahakian said. “But we don’t know if there’s a cliff beyond which you can’t reverse a change. So the sooner you catch something, the better.”

The day-to-day impact

In some ways, mental health awareness has increased during the pandemic. TV shows are flush with ads for therapy and meditation apps, like Talkspace and Calm, and companies are announcing mental health days off for staff. But those spurts of attention fail to reveal the full impact of poor mental health on people’s daily lives.

For Alex Kostka, pandemic-related stress has brought on mood swings, nightmares, and jaw pain.

He’d been working at a Whole Foods coffee bar in New York City for only about a month before the pandemic hit, suddenly anointing him an essential worker. As deaths in the city soared, Mr. Kostka continued riding the subway to work, interacting with coworkers in the store and working longer hours for just a $2-per-hour wage increase. (Months later, he’d get a $500 bonus.) It left the 28-year-old feeling constantly unsafe and helpless.

“It was hard not to break down on the subway the minute I got on it,” Mr. Kostka said.

Soon he began waking in the middle of the night with pain from clenching his jaw so tightly. Often his teeth grinding and chomping were loud enough to wake his girlfriend.

Mr. Kostka tried Talkspace, but found texting about his troubles felt impersonal. By the end of the summer, he decided to start using the seven free counseling sessions offered by his employer. That’s helped, he said. But as the sessions run out, he worries the symptoms might return if he’s unable to find a new therapist covered by his insurance.

“Eventually, I will be able to leave this behind me, but it will take time,” Mr. Kostka said. “I’m still very much a work in progress.”

How to mitigate chronic stress

When it comes to chronic stress, seeing a doctor for stomach pain, headaches, or skin rashes may address those physical symptoms. But the root cause is mental, medical experts said.

That means the solution will often involve stress-management techniques. And there’s plenty we can do to feel better:

- Exercise. Even low- to moderate-intensity physical activity can help counteract stress-induced inflammation in the body. It can also increase neuronal connections in the brain.

- Meditation and mindfulness. Research shows this can lead to positive, structural, and functional changes in the brain.

- Fostering social connections. Talking to family and friends, even virtually, or staring into a pet’s eyes can release a hormone that may counteract inflammation.

- Learning something new. Whether it’s a formal class or taking up a casual hobby, learning supports brain plasticity, the ability to change and adapt as a result of experience, which can be protective against depression and other mental illness.

“We shouldn’t think of this stressful situation as a negative sentence for the brain,” said Dr. Harkness. “Because stress changes the brain, that means positive stuff can change the brain, too. And there is plenty we can do to help ourselves feel better in the face of adversity.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

In late March, shortly after New York state closed nonessential businesses and asked people to stay home, Ashley Laderer began waking each morning with a throbbing headache.

“The pressure was so intense it felt like my head was going to explode,” recalled the 27-year-old freelance writer from Long Island.

She tried spending less time on the computer and taking over-the-counter pain medication, but the pounding kept breaking through – a constant drumbeat to accompany her equally incessant worries about COVID-19.

“Every day I lived in fear that I was going to get it and I was going to infect my whole family,” she said.

After a month and a half, Ms. Laderer decided to visit a neurologist, who ordered an MRI. But the doctor found no physical cause. The scan was clear.

Then he asked: “Are you under a lot of stress?”

excruciating headaches, episodes of hair loss, upset stomach for weeks on end, sudden outbreaks of shingles, and flare-ups of autoimmune disorders. The disparate symptoms, often in otherwise-healthy individuals, have puzzled doctors and patients alike, sometimes resulting in a series of visits to specialists with few answers. But it turns out there’s a common thread among many of these conditions, one that has been months in the making: chronic stress.

Although people often underestimate the influence of the mind on the body, a growing catalog of research shows that high levels of stress over an extended time can drastically alter physical function and affect nearly every organ system.

Now, at least 8 months into the pandemic, alongside a divisive election cycle and racial unrest, those effects are showing up in a variety of symptoms.

“The mental health component of COVID is starting to come like a tsunami,” said Jennifer Love, MD, a California-based psychiatrist and coauthor of an upcoming book on how to heal from chronic stress.

Nationwide, surveys have found increasing rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts during the pandemic. But many medical experts said it’s too soon to measure the related physical symptoms, since they generally appear months after the stress begins.

Still, some early research, such as a small Chinese study and an online survey of more than 500 people in Turkey, points to an uptick.

In the United States, data from FAIR Health, a nonprofit database that provides cost information to the health industry and consumers, showed slight to moderate increases in the percentage of medical claims related to conditions triggered or exacerbated by stress, like multiple sclerosis and shingles. The portion of claims for the autoimmune disease lupus, for example, showed one of the biggest increases – 12% this year – compared with the same period last year (January to August).

Express Scripts, a major pharmacy benefit manager, reported that prescriptions for anti-insomnia medications increased 15% early in the pandemic.

Perhaps the strongest indicator comes from doctors reporting a growing number of patients with physical symptoms for which they can’t determine a cause.

Shilpi Khetarpal, MD, a dermatologist at the Cleveland Clinic, used to see about five patients a week with stress-related hair loss. Since mid-June, that number has jumped to 20 or 25. Mostly women, ages 20-80, are reporting hair coming out in fistfuls, Dr. Khetarpal said.

In Houston, at least a dozen patients have told fertility specialist Rashmi Kudesia, MD, they’re having irregular menstrual cycles, changes in cervical discharge and breast tenderness, despite normal hormone levels.

Stress is also the culprit dentists are pointing to for the rapid increase in patients with teeth grinding, teeth fractures, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

“We, as humans, like to have the idea that we are in control of our minds and that stress isn’t a big deal,” Dr. Love said. “But it’s simply not true.”

How mental stress becomes physical

Stress causes physical changes in the body that can affect nearly every organ system.

Although symptoms of chronic stress are often dismissed as being in one’s head, the pain is very real, said Kate Harkness, PhD, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont.

When the body feels unsafe – whether it’s a physical threat of attack or a psychological fear of losing a job or catching a disease – the brain signals adrenal glands to pump stress hormones. Adrenaline and cortisol flood the body, activating the fight-or-flight response. They also disrupt bodily functions that aren’t necessary for immediate survival, like digestion and reproduction.

When the danger is over, the hormones return to normal levels. But during times of chronic stress, like a pandemic, the body keeps pumping out stress hormones until it tires itself out. This leads to increased inflammation throughout the body and brain, and a poorly functioning immune system.

Studies link chronic stress to heart disease, muscle tension, gastrointestinal issues and even physical shrinking of the hippocampus, an area of the brain associated with memory and learning. As the immune system acts up, some people can even develop new allergic reactions, Dr. Harkness said.

The good news is that many of these symptoms are reversible. But it’s important to recognize them early, especially when it comes to the brain, said Barbara Sahakian, FBA, FMedSci, a professor of clinical neuropsychology at the University of Cambridge (England).

“The brain is plastic, so we can to some extent modify it,” Dr. Sahakian said. “But we don’t know if there’s a cliff beyond which you can’t reverse a change. So the sooner you catch something, the better.”

The day-to-day impact

In some ways, mental health awareness has increased during the pandemic. TV shows are flush with ads for therapy and meditation apps, like Talkspace and Calm, and companies are announcing mental health days off for staff. But those spurts of attention fail to reveal the full impact of poor mental health on people’s daily lives.

For Alex Kostka, pandemic-related stress has brought on mood swings, nightmares, and jaw pain.

He’d been working at a Whole Foods coffee bar in New York City for only about a month before the pandemic hit, suddenly anointing him an essential worker. As deaths in the city soared, Mr. Kostka continued riding the subway to work, interacting with coworkers in the store and working longer hours for just a $2-per-hour wage increase. (Months later, he’d get a $500 bonus.) It left the 28-year-old feeling constantly unsafe and helpless.

“It was hard not to break down on the subway the minute I got on it,” Mr. Kostka said.

Soon he began waking in the middle of the night with pain from clenching his jaw so tightly. Often his teeth grinding and chomping were loud enough to wake his girlfriend.

Mr. Kostka tried Talkspace, but found texting about his troubles felt impersonal. By the end of the summer, he decided to start using the seven free counseling sessions offered by his employer. That’s helped, he said. But as the sessions run out, he worries the symptoms might return if he’s unable to find a new therapist covered by his insurance.

“Eventually, I will be able to leave this behind me, but it will take time,” Mr. Kostka said. “I’m still very much a work in progress.”

How to mitigate chronic stress

When it comes to chronic stress, seeing a doctor for stomach pain, headaches, or skin rashes may address those physical symptoms. But the root cause is mental, medical experts said.

That means the solution will often involve stress-management techniques. And there’s plenty we can do to feel better:

- Exercise. Even low- to moderate-intensity physical activity can help counteract stress-induced inflammation in the body. It can also increase neuronal connections in the brain.

- Meditation and mindfulness. Research shows this can lead to positive, structural, and functional changes in the brain.

- Fostering social connections. Talking to family and friends, even virtually, or staring into a pet’s eyes can release a hormone that may counteract inflammation.

- Learning something new. Whether it’s a formal class or taking up a casual hobby, learning supports brain plasticity, the ability to change and adapt as a result of experience, which can be protective against depression and other mental illness.

“We shouldn’t think of this stressful situation as a negative sentence for the brain,” said Dr. Harkness. “Because stress changes the brain, that means positive stuff can change the brain, too. And there is plenty we can do to help ourselves feel better in the face of adversity.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Survey: Doctors lonely, burned out in COVID-19

Patrick Ross, MD, a critical care physician at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, was plagued with increasing worry about his health and that of his family, patients, and colleagues. While distancing from his wife and daughter, he became terrified of falling ill and dying alone.

As he grew more anxious, Ross withdrew from family, colleagues, and friends, although his clinical and academic responsibilities were unaffected. He barely ate; his weight plummeted, and he began to have suicidal thoughts.

Rebecca Margolis, DO, a pediatric anesthesiologist whom Ross was mentoring, noticed something was amiss and suggested that he go to a therapist. That suggestion may have saved him.

“Once I started therapy, I no longer had suicidal ideations, but I still remained anxious on a day-to-day basis,” said Ross, who is an associate professor of clinical anesthesiology and pediatrics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “As soon as I learned to manage or mitigate the anxiety, I was no longer consumed to the degree I had been by the sense of day-to-day threat.”

Ross openly shares his story because “many other physicians may be going through versions of what I experienced, and I want to encourage them to get help if they’re feeling stressed, anxious, lonely, depressed, or burned out, and to recognize that they are not alone.”

Physicians feel a sense of betrayal

Ross’ experience, although extreme, is not unique. According to a Medscape survey of almost 7,500 physicians, about two-thirds (64%) of U.S. physicians reported experiencing more intense burnout, and close to half (46%) reported feeling more lonely and isolated during the pandemic.

“We know that stress, which was already significant in physicians, has increased dramatically for many physicians during the pandemic. That’s understandable, given the circumstances they’ve been working under,” said Christine A. Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association.

Physicians are stressed about potentially contracting the virus or infecting family members; being overworked and fatigued; witnessing wrenching scenes of patients dying alone; grieving the loss of patients, colleagues, or family members; and sometimes lacking adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), she said.

Lack of PPE has been identified as one of the most significant contributors to burnout and stress among physicians and other health care professionals. In all eight countries surveyed by Medscape, a significant number of respondents reported lacking appropriate PPE “sometimes,” “often,” or “always” when treating COVID-19 patients. Only 54% of U.S. respondents said they were always adequately protected.

The PPE shortage not only jeopardizes physical health but also has a negative effect on mental health and morale. A U.S.-based rheumatologist said, “The fact that we were sent to take care of infectious patients without proper PPE makes me feel we were betrayed in this fight.”

Not what they signed up for

Many physicians expressed fear regarding their personal safety, but that was often superseded by concern for family – especially elderly relatives or young children. (Medscape’s survey found that 9% of US respondents had immediate family members who had been diagnosed with COVID-19.)

Larissa Thomas, MD, MPH, University of California, San Francisco, said her greatest fear was bringing the virus home to her new baby and other vulnerable family members. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine and is a faculty hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

“Although physicians assume risk in our work, we didn’t sign up to care for patients without adequate protection, and our families certainly didn’t sign up for that risk, so the concern was acutely stressful,” said Thomas, who is also associate program director for the UCSF Internal Medicine Residency Program and is director of well-being for UCSF Graduate Medical Education.

The impact of stay-at-home restrictions on family members’ mental health also affected many physicians.

David Marcus, MD, residency director of the Combined Program in Emergency/Internal/Critical Care Medicine and chair of the GME Physician Wellbeing Committee at Northwell Health, Long Island, New York, said that a large stressor during the pandemic was having an elderly father with multiple comorbidities who lived alone and was unable to go out because of stay-at-home restrictions.

“I was worried not only for his physical health but also that his cognition might slip due to lack of socialization,” said Marcus.

Marcus was also worried about his preschool-age daughter, who seemed to be regressing and becoming desocialized from no longer being at school. “Fortunately, school has reopened, but it was a constant weight on my wife and me to see the impact of the lockdown on her development,” he said.

New situations create more anxiety

Being redeployed to new clinical roles in settings such as the emergency department or intensive care, which were not in their area of specialty, created much stress for physicians, Thomas said.

Physicians in private practice also had to adjust to new ways of practicing. In Medscape’s survey, 39% of U.S. physicians reported that their medical practice never closed during the pandemic. Keeping a practice open often meant learning to see patients virtually or becoming extremely vigilant about reducing the risk for contagion when seeing patients in person.

Relationships became more challenging

Social distancing during the pandemic had a negative effect on personal relationships for 44% of respondents, both in the United States and abroad.

One physician described her relationship with her partner as “more stressful” and argumentative. A rheumatologist reported experiencing frustration at having college-aged children living at home. Another respondent said that being with young children 24/7 left her “short-tempered,” and an emergency medicine physician respondent said she and her family were “driving each other crazy.”

Social distancing was not the only challenge to relationships. An orthopedist identified long, taxing work hours as contributing to a “decline in spousal harmony.”

On the other hand, some physicians said their relationships improved by developing shared insight. An emergency medicine physician wrote that he and his wife were “having more quarrels” but were “trying very hard and succeeding at understanding that much of this is due to the changes in our living situation.”

As a volunteer with New York City’s Medical Reserve Corps, Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, chose to keep his Teaneck, New Jersey–based office open and was taking overnight shifts at Lincoln Hospital in New York City during the acute physician shortage. “After my regular hospital job treating psychiatric patients and seeing patients in my private practice, I sometimes pulled 12-hour nights caring for very ill patients. It was grueling, and I came home drained and exhausted,” he recalled.

Raby’s wife, a surgical nurse, had been redeployed to care for COVID-19 patients in the ICU – a situation she found grueling as well. Adding to the stress were the “rigorous distancing and sanitation precautions we needed to practice at home.” Fear of contagion, together with exhaustion, resulted in “occasional moments of friction,” Raby acknowledged.

Still, some physicians managed to find a bit of a silver lining. “We tried to relax, get as much sleep as possible, and keep things simple, not taking on extra tasks that could be postponed,” Raby said. “It helped that we both recognized how difficult it was to reassure each other when we were stressed and scared, so we faced the crisis together, and I think it ultimately brought us closer.”

Thomas said that the pandemic has helped her to recognize what she can and cannot control and how to take things one day at a time.

“When my husband and I can both work from home, we are grateful to have that ability and grateful for the things that we do have. These small moments of gratitude have sustained us day to day,” Thomas said.

Socializing outside the box

Several physicians expressed a sense of loneliness because stay-at-home guidelines and social distancing prevented them from socializing with friends. In all countries, physician respondents to the Medscape survey reported feeling “more lonely” than prior to the pandemic. Over half (51%) of Portuguese physicians reported feeling lonelier; 48% of physicians in Brazil felt that way. The United States came in third, at 46%.

Many physicians feel cut off, even from other physicians, and are reluctant to share feelings of distress.

“Talking to colleagues about distress is an important human connection,” Margolis emphasized. “We need to rely on each other to commiserate and receive validation and comfort.”

Some institutions have formalized this process by instituting a “battle buddy” model – a term borrowed from the military – which involves pairing clinicians of similar specialty, career stage, and life circumstances to provide mutual peer support, Margolis said. A partner who notices concerning signs in the other partner can refer the person to resources for help.

Sinsky said that an organization called PeerRxMed offers physicians a chance to sign up for a “buddy,” even outside their own institution.

The importance of ‘fixing’ the workplace

Close to half (43%) of U.S. respondents to Medscape’s survey reported that their workplace offers activities to help physicians deal with grief and stress, but 39% said that their workplace does not offer this type of support, and 18% were not sure whether these services were offered.

At times of crisis, organizations need to offer “stress first aid,” Sinsky said. This includes providing for basic needs, such as child care, transportation, and healthy food, and having “open, transparent, and honest communication” from leadership regarding what is known and not known about the pandemic, clinician responsibilities, and stress reduction measures.

Marcus notes that, at his institution, psychiatric residents and other members of the psychiatry department have “stepped up and crafted process groups and peer support contexts to debrief, engage, explore productive outlets for feelings, and facilitate communication.” In particular, residents have found cognitive-behavioral therapy to be useful.

Despite the difficult situation, seeking help can be challenging for some physicians. One reason, Marcus says, is that doctors tend to think of themselves as being at the giving rather than the receiving end of help – especially during a crisis. “We do what we need to do, and we often don’t see the toll it takes on us,” he noted. Moreover, the pressure to be at the “giving” end can lead to stigma in acknowledging vulnerability.

Ross said he hopes his story will help to destigmatize reaching out for help. “It is possible that a silver lining of this terrible crisis is to normalize physicians receiving help for mental health issues.”

Marcus likewise openly shares his own experiences about struggles with burnout and depressive symptoms. “As a physician educator, I think it’s important for me to be public about these things, which validates help-seeking for residents and colleagues.”

For physicians seeking help not offered in their workplace, the Physician Support Line is a useful resource, added Margolis. She noted that its services are free and confidential.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patrick Ross, MD, a critical care physician at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, was plagued with increasing worry about his health and that of his family, patients, and colleagues. While distancing from his wife and daughter, he became terrified of falling ill and dying alone.

As he grew more anxious, Ross withdrew from family, colleagues, and friends, although his clinical and academic responsibilities were unaffected. He barely ate; his weight plummeted, and he began to have suicidal thoughts.

Rebecca Margolis, DO, a pediatric anesthesiologist whom Ross was mentoring, noticed something was amiss and suggested that he go to a therapist. That suggestion may have saved him.

“Once I started therapy, I no longer had suicidal ideations, but I still remained anxious on a day-to-day basis,” said Ross, who is an associate professor of clinical anesthesiology and pediatrics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “As soon as I learned to manage or mitigate the anxiety, I was no longer consumed to the degree I had been by the sense of day-to-day threat.”

Ross openly shares his story because “many other physicians may be going through versions of what I experienced, and I want to encourage them to get help if they’re feeling stressed, anxious, lonely, depressed, or burned out, and to recognize that they are not alone.”

Physicians feel a sense of betrayal

Ross’ experience, although extreme, is not unique. According to a Medscape survey of almost 7,500 physicians, about two-thirds (64%) of U.S. physicians reported experiencing more intense burnout, and close to half (46%) reported feeling more lonely and isolated during the pandemic.

“We know that stress, which was already significant in physicians, has increased dramatically for many physicians during the pandemic. That’s understandable, given the circumstances they’ve been working under,” said Christine A. Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association.

Physicians are stressed about potentially contracting the virus or infecting family members; being overworked and fatigued; witnessing wrenching scenes of patients dying alone; grieving the loss of patients, colleagues, or family members; and sometimes lacking adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), she said.

Lack of PPE has been identified as one of the most significant contributors to burnout and stress among physicians and other health care professionals. In all eight countries surveyed by Medscape, a significant number of respondents reported lacking appropriate PPE “sometimes,” “often,” or “always” when treating COVID-19 patients. Only 54% of U.S. respondents said they were always adequately protected.

The PPE shortage not only jeopardizes physical health but also has a negative effect on mental health and morale. A U.S.-based rheumatologist said, “The fact that we were sent to take care of infectious patients without proper PPE makes me feel we were betrayed in this fight.”

Not what they signed up for

Many physicians expressed fear regarding their personal safety, but that was often superseded by concern for family – especially elderly relatives or young children. (Medscape’s survey found that 9% of US respondents had immediate family members who had been diagnosed with COVID-19.)

Larissa Thomas, MD, MPH, University of California, San Francisco, said her greatest fear was bringing the virus home to her new baby and other vulnerable family members. Thomas is associate clinical professor of medicine and is a faculty hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital.

“Although physicians assume risk in our work, we didn’t sign up to care for patients without adequate protection, and our families certainly didn’t sign up for that risk, so the concern was acutely stressful,” said Thomas, who is also associate program director for the UCSF Internal Medicine Residency Program and is director of well-being for UCSF Graduate Medical Education.

The impact of stay-at-home restrictions on family members’ mental health also affected many physicians.

David Marcus, MD, residency director of the Combined Program in Emergency/Internal/Critical Care Medicine and chair of the GME Physician Wellbeing Committee at Northwell Health, Long Island, New York, said that a large stressor during the pandemic was having an elderly father with multiple comorbidities who lived alone and was unable to go out because of stay-at-home restrictions.

“I was worried not only for his physical health but also that his cognition might slip due to lack of socialization,” said Marcus.

Marcus was also worried about his preschool-age daughter, who seemed to be regressing and becoming desocialized from no longer being at school. “Fortunately, school has reopened, but it was a constant weight on my wife and me to see the impact of the lockdown on her development,” he said.

New situations create more anxiety

Being redeployed to new clinical roles in settings such as the emergency department or intensive care, which were not in their area of specialty, created much stress for physicians, Thomas said.

Physicians in private practice also had to adjust to new ways of practicing. In Medscape’s survey, 39% of U.S. physicians reported that their medical practice never closed during the pandemic. Keeping a practice open often meant learning to see patients virtually or becoming extremely vigilant about reducing the risk for contagion when seeing patients in person.

Relationships became more challenging

Social distancing during the pandemic had a negative effect on personal relationships for 44% of respondents, both in the United States and abroad.

One physician described her relationship with her partner as “more stressful” and argumentative. A rheumatologist reported experiencing frustration at having college-aged children living at home. Another respondent said that being with young children 24/7 left her “short-tempered,” and an emergency medicine physician respondent said she and her family were “driving each other crazy.”

Social distancing was not the only challenge to relationships. An orthopedist identified long, taxing work hours as contributing to a “decline in spousal harmony.”

On the other hand, some physicians said their relationships improved by developing shared insight. An emergency medicine physician wrote that he and his wife were “having more quarrels” but were “trying very hard and succeeding at understanding that much of this is due to the changes in our living situation.”

As a volunteer with New York City’s Medical Reserve Corps, Wilfrid Noel Raby, PhD, MD, adjunct clinical professor of psychiatry, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, chose to keep his Teaneck, New Jersey–based office open and was taking overnight shifts at Lincoln Hospital in New York City during the acute physician shortage. “After my regular hospital job treating psychiatric patients and seeing patients in my private practice, I sometimes pulled 12-hour nights caring for very ill patients. It was grueling, and I came home drained and exhausted,” he recalled.

Raby’s wife, a surgical nurse, had been redeployed to care for COVID-19 patients in the ICU – a situation she found grueling as well. Adding to the stress were the “rigorous distancing and sanitation precautions we needed to practice at home.” Fear of contagion, together with exhaustion, resulted in “occasional moments of friction,” Raby acknowledged.

Still, some physicians managed to find a bit of a silver lining. “We tried to relax, get as much sleep as possible, and keep things simple, not taking on extra tasks that could be postponed,” Raby said. “It helped that we both recognized how difficult it was to reassure each other when we were stressed and scared, so we faced the crisis together, and I think it ultimately brought us closer.”

Thomas said that the pandemic has helped her to recognize what she can and cannot control and how to take things one day at a time.

“When my husband and I can both work from home, we are grateful to have that ability and grateful for the things that we do have. These small moments of gratitude have sustained us day to day,” Thomas said.

Socializing outside the box

Several physicians expressed a sense of loneliness because stay-at-home guidelines and social distancing prevented them from socializing with friends. In all countries, physician respondents to the Medscape survey reported feeling “more lonely” than prior to the pandemic. Over half (51%) of Portuguese physicians reported feeling lonelier; 48% of physicians in Brazil felt that way. The United States came in third, at 46%.

Many physicians feel cut off, even from other physicians, and are reluctant to share feelings of distress.

“Talking to colleagues about distress is an important human connection,” Margolis emphasized. “We need to rely on each other to commiserate and receive validation and comfort.”

Some institutions have formalized this process by instituting a “battle buddy” model – a term borrowed from the military – which involves pairing clinicians of similar specialty, career stage, and life circumstances to provide mutual peer support, Margolis said. A partner who notices concerning signs in the other partner can refer the person to resources for help.

Sinsky said that an organization called PeerRxMed offers physicians a chance to sign up for a “buddy,” even outside their own institution.

The importance of ‘fixing’ the workplace

Close to half (43%) of U.S. respondents to Medscape’s survey reported that their workplace offers activities to help physicians deal with grief and stress, but 39% said that their workplace does not offer this type of support, and 18% were not sure whether these services were offered.

At times of crisis, organizations need to offer “stress first aid,” Sinsky said. This includes providing for basic needs, such as child care, transportation, and healthy food, and having “open, transparent, and honest communication” from leadership regarding what is known and not known about the pandemic, clinician responsibilities, and stress reduction measures.

Marcus notes that, at his institution, psychiatric residents and other members of the psychiatry department have “stepped up and crafted process groups and peer support contexts to debrief, engage, explore productive outlets for feelings, and facilitate communication.” In particular, residents have found cognitive-behavioral therapy to be useful.

Despite the difficult situation, seeking help can be challenging for some physicians. One reason, Marcus says, is that doctors tend to think of themselves as being at the giving rather than the receiving end of help – especially during a crisis. “We do what we need to do, and we often don’t see the toll it takes on us,” he noted. Moreover, the pressure to be at the “giving” end can lead to stigma in acknowledging vulnerability.

Ross said he hopes his story will help to destigmatize reaching out for help. “It is possible that a silver lining of this terrible crisis is to normalize physicians receiving help for mental health issues.”

Marcus likewise openly shares his own experiences about struggles with burnout and depressive symptoms. “As a physician educator, I think it’s important for me to be public about these things, which validates help-seeking for residents and colleagues.”

For physicians seeking help not offered in their workplace, the Physician Support Line is a useful resource, added Margolis. She noted that its services are free and confidential.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patrick Ross, MD, a critical care physician at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, was plagued with increasing worry about his health and that of his family, patients, and colleagues. While distancing from his wife and daughter, he became terrified of falling ill and dying alone.

As he grew more anxious, Ross withdrew from family, colleagues, and friends, although his clinical and academic responsibilities were unaffected. He barely ate; his weight plummeted, and he began to have suicidal thoughts.

Rebecca Margolis, DO, a pediatric anesthesiologist whom Ross was mentoring, noticed something was amiss and suggested that he go to a therapist. That suggestion may have saved him.

“Once I started therapy, I no longer had suicidal ideations, but I still remained anxious on a day-to-day basis,” said Ross, who is an associate professor of clinical anesthesiology and pediatrics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. “As soon as I learned to manage or mitigate the anxiety, I was no longer consumed to the degree I had been by the sense of day-to-day threat.”

Ross openly shares his story because “many other physicians may be going through versions of what I experienced, and I want to encourage them to get help if they’re feeling stressed, anxious, lonely, depressed, or burned out, and to recognize that they are not alone.”

Physicians feel a sense of betrayal

Ross’ experience, although extreme, is not unique. According to a Medscape survey of almost 7,500 physicians, about two-thirds (64%) of U.S. physicians reported experiencing more intense burnout, and close to half (46%) reported feeling more lonely and isolated during the pandemic.

“We know that stress, which was already significant in physicians, has increased dramatically for many physicians during the pandemic. That’s understandable, given the circumstances they’ve been working under,” said Christine A. Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association.

Physicians are stressed about potentially contracting the virus or infecting family members; being overworked and fatigued; witnessing wrenching scenes of patients dying alone; grieving the loss of patients, colleagues, or family members; and sometimes lacking adequate personal protective equipment (PPE), she said.

Lack of PPE has been identified as one of the most significant contributors to burnout and stress among physicians and other health care professionals. In all eight countries surveyed by Medscape, a significant number of respondents reported lacking appropriate PPE “sometimes,” “often,” or “always” when treating COVID-19 patients. Only 54% of U.S. respondents said they were always adequately protected.