User login

A plane crash interrupts a doctor’s vacation

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime – and sometimes physicians find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. “Is There a Doctor in the House?” is a new series telling these stories.

When the plane crashed, I was asleep. I had arrived the evening before with my wife and three sons at a house on Kezar Lake on the Maine–New Hampshire border. I jumped out of bed and ran downstairs. My kids had been watching a float plane circling and gliding along the lake. It had crashed into the water and flipped upside down. My oldest brother-in-law jumped into his ski boat and we sped out to the scene.

All we can see are the plane’s pontoons. The rest is underwater. A woman has already surfaced, screaming. I dive in.

I find the woman’s husband and 3-year-old son struggling to get free from the plane through the smashed windshield. They manage to get to the surface. The pilot is dead, impaled through the chest by the left wing strut.

The big problem: A little girl, whom I would learn later is named Lauren, remained trapped. The water is murky but I can see her, a 5- or 6-year-old girl with this long hair, strapped in upside down and unconscious.

The mom and I dive down over and over, pulling and ripping at the door. We cannot get it open. Finally, I’m able to bend the door open enough where I can reach in, but I can’t undo the seatbelt. In my mind, I’m debating, should I try and go through the front windshield? I’m getting really tired, I can tell there’s fuel in the water, and I don’t want to drown in the plane. So I pop up to the surface and yell, “Does anyone have a knife?”

My brother-in-law shoots back to shore in the boat, screaming, “Get a knife!” My niece gets in the boat with one. I’m standing on the pontoon, and my niece is in the front of the boat calling, “Uncle Todd! Uncle Todd!” and she throws the knife. It goes way over my head. I can’t even jump for it, it’s so high.

I have to get the knife. So, I dive into the water to try and find it. Somehow, the black knife has landed on the white wing, 4 or 5 feet under the water. Pure luck. It could have sunk down a hundred feet into the lake. I grab the knife and hand it to the mom, Beth. She’s able to cut the seatbelt, and we both pull Lauren to the surface.

I lay her out on the pontoon. She has no pulse and her pupils are fixed and dilated. Her mom is yelling, “She’s dead, isn’t she?” I start CPR. My skin and eyes are burning from the airplane fuel in the water. I get her breathing, and her heart comes back very quickly. Lauren starts to vomit and I’m trying to keep her airway clear. She’s breathing spontaneously and she has a pulse, so I decide it’s time to move her to shore.

We pull the boat up to the dock and Lauren’s now having anoxic seizures. Her brain has been without oxygen, and now she’s getting perfused again. We get her to shore and lay her on the lawn. I’m still doing mouth-to-mouth, but she’s seizing like crazy, and I don’t have any way to control that. Beth is crying and wants to hold her daughter gently while I’m working.

Someone had called 911, and finally this dude shows up with an ambulance, and it’s like something out of World War II. All he has is an oxygen tank, but the mask is old and cracked. It’s too big for Lauren, but it sort of fits me, so I’m sucking in oxygen and blowing it into the girl’s mouth. I’m doing whatever I can, but I don’t have an IV to start. I have no fluids. I got nothing.

As it happens, I’d done my emergency medicine training at Maine Medical Center, so I tell someone to call them and get a Life Flight chopper. We have to drive somewhere where the chopper can land, so we take the ambulance to the parking lot of the closest store called the Wicked Good Store. That’s a common thing in Maine. Everything is “wicked good.”

The whole town is there by that point. The chopper arrives. The ambulance doors pop open and a woman says, “Todd?” And I say, “Heather?”

Heather is an emergency flight nurse whom I’d trained with many years ago. There’s immediate trust. She has all the right equipment. We put in breathing tubes and IVs. We stop Lauren from seizing. The kid is soon stable.

There is only one extra seat in the chopper, so I tell Beth to go. They take off.

Suddenly, I begin to doubt my decision. Lauren had been underwater for 15 minutes at minimum. I know how long that is. Did I do the right thing? Did I resuscitate a brain-dead child? I didn’t think about it at the time, but if that patient had come to me in the emergency department, I’m honestly not sure what I would have done.

So, I go home. And I don’t get a call. The FAA and sheriff arrive to take statements from us. I don’t hear from anyone.

The next day I start calling. No one will tell me anything, so I finally get to one of the pediatric ICU attendings who had trained me. He says Lauren literally woke up and said, “I have to go pee.” And that was it. She was 100% normal. I couldn’t believe it.

Here’s a theory: In kids, there’s something called the glottic reflex. I think her glottic reflex went off as soon as she hit the water, which basically closed her airway. So when she passed out, she could never get enough water in her lungs and still had enough air in there to keep her alive. Later, I got a call from her uncle. He could barely get the words out because he was in tears. He said Lauren was doing beautifully.

Three days later, I drove to Lauren’s house with my wife and kids. I had her read to me. I watched her play on the jungle gym for motor function. All sorts of stuff. She was totally normal.

Beth told us that the night before the accident, her mother had given the women in her family what she called a “miracle bracelet,” a bracelet that is supposed to give you one miracle in your life. Beth said she had the bracelet on her wrist the day of the accident, and now it’s gone. “Saving Lauren’s life was my miracle,” she said.

Funny thing: For 20 years, I ran all the EMS, police, fire, ambulance, in Boulder, Colo., where I live. I wrote all the protocols, and I would never advise any of my paramedics to dive into jet fuel to save someone. That was risky. But at the time, it was totally automatic. I think it taught me not to give up in certain situations, because you really don’t know.

Dr. Dorfman is an emergency medicine physician in Boulder, Colo., and medical director at Cedalion Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime – and sometimes physicians find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. “Is There a Doctor in the House?” is a new series telling these stories.

When the plane crashed, I was asleep. I had arrived the evening before with my wife and three sons at a house on Kezar Lake on the Maine–New Hampshire border. I jumped out of bed and ran downstairs. My kids had been watching a float plane circling and gliding along the lake. It had crashed into the water and flipped upside down. My oldest brother-in-law jumped into his ski boat and we sped out to the scene.

All we can see are the plane’s pontoons. The rest is underwater. A woman has already surfaced, screaming. I dive in.

I find the woman’s husband and 3-year-old son struggling to get free from the plane through the smashed windshield. They manage to get to the surface. The pilot is dead, impaled through the chest by the left wing strut.

The big problem: A little girl, whom I would learn later is named Lauren, remained trapped. The water is murky but I can see her, a 5- or 6-year-old girl with this long hair, strapped in upside down and unconscious.

The mom and I dive down over and over, pulling and ripping at the door. We cannot get it open. Finally, I’m able to bend the door open enough where I can reach in, but I can’t undo the seatbelt. In my mind, I’m debating, should I try and go through the front windshield? I’m getting really tired, I can tell there’s fuel in the water, and I don’t want to drown in the plane. So I pop up to the surface and yell, “Does anyone have a knife?”

My brother-in-law shoots back to shore in the boat, screaming, “Get a knife!” My niece gets in the boat with one. I’m standing on the pontoon, and my niece is in the front of the boat calling, “Uncle Todd! Uncle Todd!” and she throws the knife. It goes way over my head. I can’t even jump for it, it’s so high.

I have to get the knife. So, I dive into the water to try and find it. Somehow, the black knife has landed on the white wing, 4 or 5 feet under the water. Pure luck. It could have sunk down a hundred feet into the lake. I grab the knife and hand it to the mom, Beth. She’s able to cut the seatbelt, and we both pull Lauren to the surface.

I lay her out on the pontoon. She has no pulse and her pupils are fixed and dilated. Her mom is yelling, “She’s dead, isn’t she?” I start CPR. My skin and eyes are burning from the airplane fuel in the water. I get her breathing, and her heart comes back very quickly. Lauren starts to vomit and I’m trying to keep her airway clear. She’s breathing spontaneously and she has a pulse, so I decide it’s time to move her to shore.

We pull the boat up to the dock and Lauren’s now having anoxic seizures. Her brain has been without oxygen, and now she’s getting perfused again. We get her to shore and lay her on the lawn. I’m still doing mouth-to-mouth, but she’s seizing like crazy, and I don’t have any way to control that. Beth is crying and wants to hold her daughter gently while I’m working.

Someone had called 911, and finally this dude shows up with an ambulance, and it’s like something out of World War II. All he has is an oxygen tank, but the mask is old and cracked. It’s too big for Lauren, but it sort of fits me, so I’m sucking in oxygen and blowing it into the girl’s mouth. I’m doing whatever I can, but I don’t have an IV to start. I have no fluids. I got nothing.

As it happens, I’d done my emergency medicine training at Maine Medical Center, so I tell someone to call them and get a Life Flight chopper. We have to drive somewhere where the chopper can land, so we take the ambulance to the parking lot of the closest store called the Wicked Good Store. That’s a common thing in Maine. Everything is “wicked good.”

The whole town is there by that point. The chopper arrives. The ambulance doors pop open and a woman says, “Todd?” And I say, “Heather?”

Heather is an emergency flight nurse whom I’d trained with many years ago. There’s immediate trust. She has all the right equipment. We put in breathing tubes and IVs. We stop Lauren from seizing. The kid is soon stable.

There is only one extra seat in the chopper, so I tell Beth to go. They take off.

Suddenly, I begin to doubt my decision. Lauren had been underwater for 15 minutes at minimum. I know how long that is. Did I do the right thing? Did I resuscitate a brain-dead child? I didn’t think about it at the time, but if that patient had come to me in the emergency department, I’m honestly not sure what I would have done.

So, I go home. And I don’t get a call. The FAA and sheriff arrive to take statements from us. I don’t hear from anyone.

The next day I start calling. No one will tell me anything, so I finally get to one of the pediatric ICU attendings who had trained me. He says Lauren literally woke up and said, “I have to go pee.” And that was it. She was 100% normal. I couldn’t believe it.

Here’s a theory: In kids, there’s something called the glottic reflex. I think her glottic reflex went off as soon as she hit the water, which basically closed her airway. So when she passed out, she could never get enough water in her lungs and still had enough air in there to keep her alive. Later, I got a call from her uncle. He could barely get the words out because he was in tears. He said Lauren was doing beautifully.

Three days later, I drove to Lauren’s house with my wife and kids. I had her read to me. I watched her play on the jungle gym for motor function. All sorts of stuff. She was totally normal.

Beth told us that the night before the accident, her mother had given the women in her family what she called a “miracle bracelet,” a bracelet that is supposed to give you one miracle in your life. Beth said she had the bracelet on her wrist the day of the accident, and now it’s gone. “Saving Lauren’s life was my miracle,” she said.

Funny thing: For 20 years, I ran all the EMS, police, fire, ambulance, in Boulder, Colo., where I live. I wrote all the protocols, and I would never advise any of my paramedics to dive into jet fuel to save someone. That was risky. But at the time, it was totally automatic. I think it taught me not to give up in certain situations, because you really don’t know.

Dr. Dorfman is an emergency medicine physician in Boulder, Colo., and medical director at Cedalion Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Emergencies happen anywhere, anytime – and sometimes physicians find themselves in situations where they are the only ones who can help. “Is There a Doctor in the House?” is a new series telling these stories.

When the plane crashed, I was asleep. I had arrived the evening before with my wife and three sons at a house on Kezar Lake on the Maine–New Hampshire border. I jumped out of bed and ran downstairs. My kids had been watching a float plane circling and gliding along the lake. It had crashed into the water and flipped upside down. My oldest brother-in-law jumped into his ski boat and we sped out to the scene.

All we can see are the plane’s pontoons. The rest is underwater. A woman has already surfaced, screaming. I dive in.

I find the woman’s husband and 3-year-old son struggling to get free from the plane through the smashed windshield. They manage to get to the surface. The pilot is dead, impaled through the chest by the left wing strut.

The big problem: A little girl, whom I would learn later is named Lauren, remained trapped. The water is murky but I can see her, a 5- or 6-year-old girl with this long hair, strapped in upside down and unconscious.

The mom and I dive down over and over, pulling and ripping at the door. We cannot get it open. Finally, I’m able to bend the door open enough where I can reach in, but I can’t undo the seatbelt. In my mind, I’m debating, should I try and go through the front windshield? I’m getting really tired, I can tell there’s fuel in the water, and I don’t want to drown in the plane. So I pop up to the surface and yell, “Does anyone have a knife?”

My brother-in-law shoots back to shore in the boat, screaming, “Get a knife!” My niece gets in the boat with one. I’m standing on the pontoon, and my niece is in the front of the boat calling, “Uncle Todd! Uncle Todd!” and she throws the knife. It goes way over my head. I can’t even jump for it, it’s so high.

I have to get the knife. So, I dive into the water to try and find it. Somehow, the black knife has landed on the white wing, 4 or 5 feet under the water. Pure luck. It could have sunk down a hundred feet into the lake. I grab the knife and hand it to the mom, Beth. She’s able to cut the seatbelt, and we both pull Lauren to the surface.

I lay her out on the pontoon. She has no pulse and her pupils are fixed and dilated. Her mom is yelling, “She’s dead, isn’t she?” I start CPR. My skin and eyes are burning from the airplane fuel in the water. I get her breathing, and her heart comes back very quickly. Lauren starts to vomit and I’m trying to keep her airway clear. She’s breathing spontaneously and she has a pulse, so I decide it’s time to move her to shore.

We pull the boat up to the dock and Lauren’s now having anoxic seizures. Her brain has been without oxygen, and now she’s getting perfused again. We get her to shore and lay her on the lawn. I’m still doing mouth-to-mouth, but she’s seizing like crazy, and I don’t have any way to control that. Beth is crying and wants to hold her daughter gently while I’m working.

Someone had called 911, and finally this dude shows up with an ambulance, and it’s like something out of World War II. All he has is an oxygen tank, but the mask is old and cracked. It’s too big for Lauren, but it sort of fits me, so I’m sucking in oxygen and blowing it into the girl’s mouth. I’m doing whatever I can, but I don’t have an IV to start. I have no fluids. I got nothing.

As it happens, I’d done my emergency medicine training at Maine Medical Center, so I tell someone to call them and get a Life Flight chopper. We have to drive somewhere where the chopper can land, so we take the ambulance to the parking lot of the closest store called the Wicked Good Store. That’s a common thing in Maine. Everything is “wicked good.”

The whole town is there by that point. The chopper arrives. The ambulance doors pop open and a woman says, “Todd?” And I say, “Heather?”

Heather is an emergency flight nurse whom I’d trained with many years ago. There’s immediate trust. She has all the right equipment. We put in breathing tubes and IVs. We stop Lauren from seizing. The kid is soon stable.

There is only one extra seat in the chopper, so I tell Beth to go. They take off.

Suddenly, I begin to doubt my decision. Lauren had been underwater for 15 minutes at minimum. I know how long that is. Did I do the right thing? Did I resuscitate a brain-dead child? I didn’t think about it at the time, but if that patient had come to me in the emergency department, I’m honestly not sure what I would have done.

So, I go home. And I don’t get a call. The FAA and sheriff arrive to take statements from us. I don’t hear from anyone.

The next day I start calling. No one will tell me anything, so I finally get to one of the pediatric ICU attendings who had trained me. He says Lauren literally woke up and said, “I have to go pee.” And that was it. She was 100% normal. I couldn’t believe it.

Here’s a theory: In kids, there’s something called the glottic reflex. I think her glottic reflex went off as soon as she hit the water, which basically closed her airway. So when she passed out, she could never get enough water in her lungs and still had enough air in there to keep her alive. Later, I got a call from her uncle. He could barely get the words out because he was in tears. He said Lauren was doing beautifully.

Three days later, I drove to Lauren’s house with my wife and kids. I had her read to me. I watched her play on the jungle gym for motor function. All sorts of stuff. She was totally normal.

Beth told us that the night before the accident, her mother had given the women in her family what she called a “miracle bracelet,” a bracelet that is supposed to give you one miracle in your life. Beth said she had the bracelet on her wrist the day of the accident, and now it’s gone. “Saving Lauren’s life was my miracle,” she said.

Funny thing: For 20 years, I ran all the EMS, police, fire, ambulance, in Boulder, Colo., where I live. I wrote all the protocols, and I would never advise any of my paramedics to dive into jet fuel to save someone. That was risky. But at the time, it was totally automatic. I think it taught me not to give up in certain situations, because you really don’t know.

Dr. Dorfman is an emergency medicine physician in Boulder, Colo., and medical director at Cedalion Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sick call

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Keeping up with the evidence (and the residents)

I work with medical students nearly every day that I see patients. I recently mentioned to a student that I have a limited working knowledge of the brand names of diabetes medications released in the past 10 years. Just like the M3s, I need the full generic name to know whether a medication is a GLP-1 inhibitor or a DPP-4 inhibitor, because I know that “flozins” are SGLT-2 inhibitors and “glutides” are GLP-1 agonists. The combined efforts of an ambulatory care pharmacist and some flashcards have helped me to better understand how they work and which ones to prescribe when. Meanwhile, the residents are capably counseling on the adverse effects of the latest diabetes agent, while I am googling its generic name.

The premise of science is continuous discovery. In the first 10 months of 2022, the US Food & Drug Administration approved more than 2 dozen new medications, almost 100 new generics, and new indications for dozens more.1,2 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued 13 new or reaffirmed recommendations in the first 10 months of 2022, and it is just one of dozens of bodies that issue guidelines relevant to primary care.3 PubMed indexes more than a million new articles each year. Learning new information and changing practice are crucial to being an effective clinician.

In this edition of JFP, Covey and Cagle4 write about updates to the USPSTF’s lung cancer screening guidelines. The authors reference changing evidence that led to the revised recommendations. When the original guideline was released in 2013, it drew on the best available evidence at the time.5 The National Lung Screening Trial, which looked at CT scanning compared with chest x-rays as screening tests for lung cancer, was groundbreaking in its methods and results.6 However, it was not without its flaws. It enrolled < 5% Black patients, and so the recommendations for age cutoffs and pack-year cutoffs were made based on the majority White population from the trial.

Black patients experience a higher mortality from lung cancer and are diagnosed at an earlier age and a lower cumulative pack-year exposure than White patients.7 Other studies have explored the social and political factors that lead to these disparities, which range from access to care to racial segregation of neighborhoods and tobacco marketing practices.7 When the USPSTF performed its periodic update of the guideline, it had access to additional research. The updates reflect the new information.

Every physician has a responsibility to find a way to adapt to important new information in medicine. Not using SGLT-2 inhibitors in the management of diabetes would be substandard care, and my patients would suffer for it. Not adopting the new lung cancer screening recommendations would exclude patients most at risk of lung cancer and allow disparities in lung cancer morbidity and mortality to grow.7,8Understanding the evidence behind the recommendations also reminds me that the guidelines will change again. These recommendations are no more static than the first guidelines were. I’ll be ready when the next update comes, and I’ll have the medical students and residents to keep me sharp.

1. US Food & Drug Administration. Novel drug approvals for 2022. Accessed October 27. 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/novel-drug-approvals-2022

2. US Food & Drug Administration. First generic drug approvals. Accessed October 27. 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-and-biologic-approval-and-ind-activity-reports/first-generic-drug-approvals

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendations. Accessed October 27, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/topic_search_results?topic_status=P

4. Covey CL, Cagle SD. Lung cancer screening: New evidence, updated guidance. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:398-402;415.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Lung cancer: screening. December 31, 2013. Accessed October 27, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening-december-2013

6. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

7. Pinheiro LC, Groner L, Soroka O, et al. Analysis of eligibility for lung cancer screening by race after 2021 changes to US Preventive Services Task Force screening guidelines. JAMA network open. 2022;5:e2229741. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29741

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:962-970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117

I work with medical students nearly every day that I see patients. I recently mentioned to a student that I have a limited working knowledge of the brand names of diabetes medications released in the past 10 years. Just like the M3s, I need the full generic name to know whether a medication is a GLP-1 inhibitor or a DPP-4 inhibitor, because I know that “flozins” are SGLT-2 inhibitors and “glutides” are GLP-1 agonists. The combined efforts of an ambulatory care pharmacist and some flashcards have helped me to better understand how they work and which ones to prescribe when. Meanwhile, the residents are capably counseling on the adverse effects of the latest diabetes agent, while I am googling its generic name.

The premise of science is continuous discovery. In the first 10 months of 2022, the US Food & Drug Administration approved more than 2 dozen new medications, almost 100 new generics, and new indications for dozens more.1,2 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued 13 new or reaffirmed recommendations in the first 10 months of 2022, and it is just one of dozens of bodies that issue guidelines relevant to primary care.3 PubMed indexes more than a million new articles each year. Learning new information and changing practice are crucial to being an effective clinician.

In this edition of JFP, Covey and Cagle4 write about updates to the USPSTF’s lung cancer screening guidelines. The authors reference changing evidence that led to the revised recommendations. When the original guideline was released in 2013, it drew on the best available evidence at the time.5 The National Lung Screening Trial, which looked at CT scanning compared with chest x-rays as screening tests for lung cancer, was groundbreaking in its methods and results.6 However, it was not without its flaws. It enrolled < 5% Black patients, and so the recommendations for age cutoffs and pack-year cutoffs were made based on the majority White population from the trial.

Black patients experience a higher mortality from lung cancer and are diagnosed at an earlier age and a lower cumulative pack-year exposure than White patients.7 Other studies have explored the social and political factors that lead to these disparities, which range from access to care to racial segregation of neighborhoods and tobacco marketing practices.7 When the USPSTF performed its periodic update of the guideline, it had access to additional research. The updates reflect the new information.

Every physician has a responsibility to find a way to adapt to important new information in medicine. Not using SGLT-2 inhibitors in the management of diabetes would be substandard care, and my patients would suffer for it. Not adopting the new lung cancer screening recommendations would exclude patients most at risk of lung cancer and allow disparities in lung cancer morbidity and mortality to grow.7,8Understanding the evidence behind the recommendations also reminds me that the guidelines will change again. These recommendations are no more static than the first guidelines were. I’ll be ready when the next update comes, and I’ll have the medical students and residents to keep me sharp.

I work with medical students nearly every day that I see patients. I recently mentioned to a student that I have a limited working knowledge of the brand names of diabetes medications released in the past 10 years. Just like the M3s, I need the full generic name to know whether a medication is a GLP-1 inhibitor or a DPP-4 inhibitor, because I know that “flozins” are SGLT-2 inhibitors and “glutides” are GLP-1 agonists. The combined efforts of an ambulatory care pharmacist and some flashcards have helped me to better understand how they work and which ones to prescribe when. Meanwhile, the residents are capably counseling on the adverse effects of the latest diabetes agent, while I am googling its generic name.

The premise of science is continuous discovery. In the first 10 months of 2022, the US Food & Drug Administration approved more than 2 dozen new medications, almost 100 new generics, and new indications for dozens more.1,2 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued 13 new or reaffirmed recommendations in the first 10 months of 2022, and it is just one of dozens of bodies that issue guidelines relevant to primary care.3 PubMed indexes more than a million new articles each year. Learning new information and changing practice are crucial to being an effective clinician.

In this edition of JFP, Covey and Cagle4 write about updates to the USPSTF’s lung cancer screening guidelines. The authors reference changing evidence that led to the revised recommendations. When the original guideline was released in 2013, it drew on the best available evidence at the time.5 The National Lung Screening Trial, which looked at CT scanning compared with chest x-rays as screening tests for lung cancer, was groundbreaking in its methods and results.6 However, it was not without its flaws. It enrolled < 5% Black patients, and so the recommendations for age cutoffs and pack-year cutoffs were made based on the majority White population from the trial.

Black patients experience a higher mortality from lung cancer and are diagnosed at an earlier age and a lower cumulative pack-year exposure than White patients.7 Other studies have explored the social and political factors that lead to these disparities, which range from access to care to racial segregation of neighborhoods and tobacco marketing practices.7 When the USPSTF performed its periodic update of the guideline, it had access to additional research. The updates reflect the new information.

Every physician has a responsibility to find a way to adapt to important new information in medicine. Not using SGLT-2 inhibitors in the management of diabetes would be substandard care, and my patients would suffer for it. Not adopting the new lung cancer screening recommendations would exclude patients most at risk of lung cancer and allow disparities in lung cancer morbidity and mortality to grow.7,8Understanding the evidence behind the recommendations also reminds me that the guidelines will change again. These recommendations are no more static than the first guidelines were. I’ll be ready when the next update comes, and I’ll have the medical students and residents to keep me sharp.

1. US Food & Drug Administration. Novel drug approvals for 2022. Accessed October 27. 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/novel-drug-approvals-2022

2. US Food & Drug Administration. First generic drug approvals. Accessed October 27. 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-and-biologic-approval-and-ind-activity-reports/first-generic-drug-approvals

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendations. Accessed October 27, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/topic_search_results?topic_status=P

4. Covey CL, Cagle SD. Lung cancer screening: New evidence, updated guidance. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:398-402;415.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Lung cancer: screening. December 31, 2013. Accessed October 27, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening-december-2013

6. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

7. Pinheiro LC, Groner L, Soroka O, et al. Analysis of eligibility for lung cancer screening by race after 2021 changes to US Preventive Services Task Force screening guidelines. JAMA network open. 2022;5:e2229741. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29741

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:962-970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117

1. US Food & Drug Administration. Novel drug approvals for 2022. Accessed October 27. 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/novel-drug-approvals-2022

2. US Food & Drug Administration. First generic drug approvals. Accessed October 27. 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-and-biologic-approval-and-ind-activity-reports/first-generic-drug-approvals

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendations. Accessed October 27, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/topic_search_results?topic_status=P

4. Covey CL, Cagle SD. Lung cancer screening: New evidence, updated guidance. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:398-402;415.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Lung cancer: screening. December 31, 2013. Accessed October 27, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening-december-2013

6. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873

7. Pinheiro LC, Groner L, Soroka O, et al. Analysis of eligibility for lung cancer screening by race after 2021 changes to US Preventive Services Task Force screening guidelines. JAMA network open. 2022;5:e2229741. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.29741

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325:962-970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117

New recommendations for hyperglycemia management

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

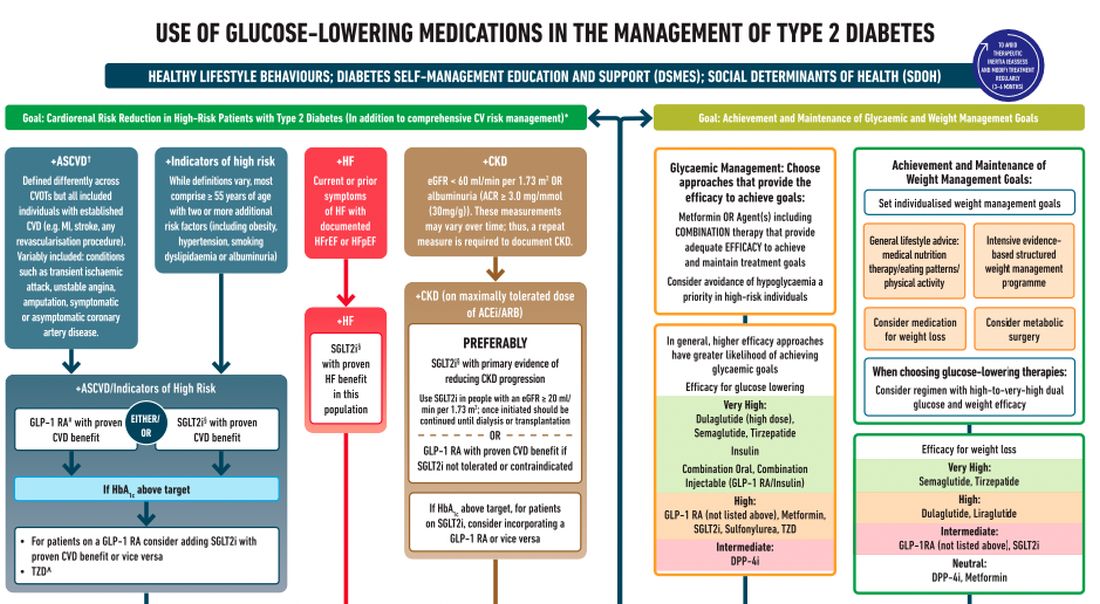

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

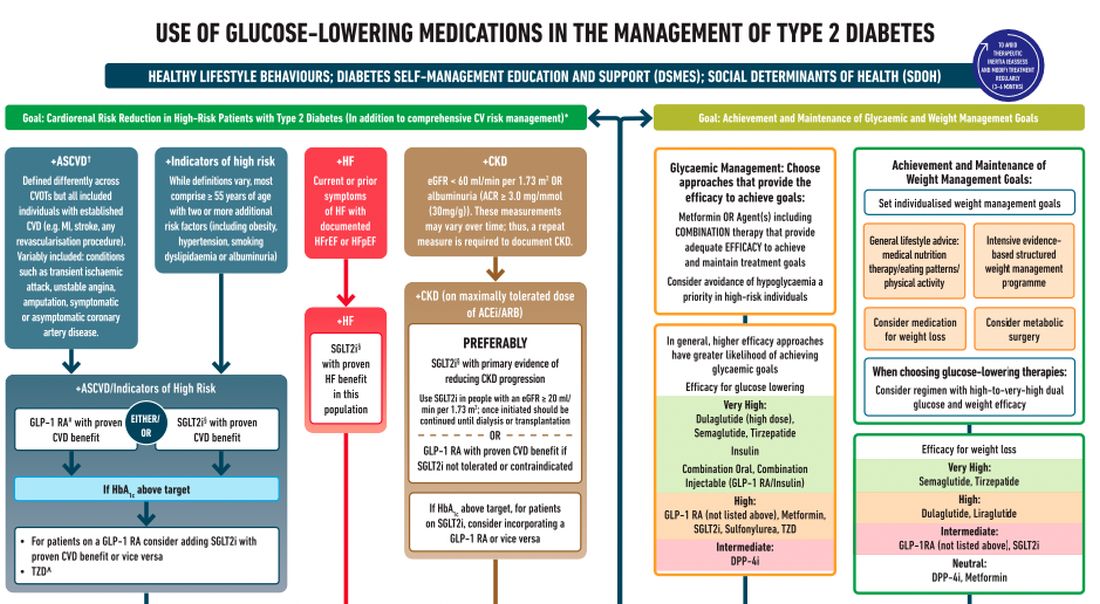

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’m Dr. Neil Skolnik. Today we’re going to talk about the consensus report by the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes on the management of hyperglycemia.

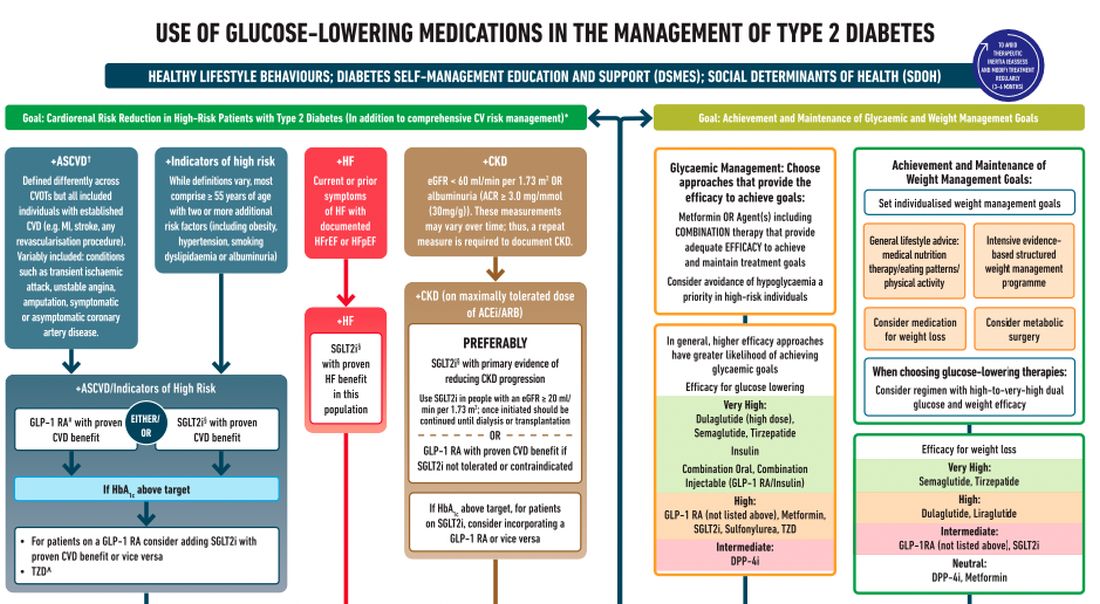

After lifestyle modifications, metformin is no longer the go-to drug for every patient in the management of hyperglycemia. It is recommended that we assess each patient’s personal characteristics in deciding what medication to prescribe. For patients at high cardiorenal risk, refer to the left side of the algorithm and to the right side for all other patients.

Cardiovascular disease. First, assess whether the patient is at high risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or already has ASCVD. How is ASCVD defined? Either coronary artery disease (a history of a myocardial infarction [MI] or coronary disease), peripheral vascular disease, stroke, or transient ischemic attack.

What is high risk for ASCVD? Diabetes in someone older than 55 years with two or more additional risk factors. If the patient is at high risk for or has existing ASCVD then it is recommended to prescribe a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonist with proven CVD benefit or an sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor with proven CVD benefit.

For patients at very high risk for ASCVD, it might be reasonable to combine both agents. The recommendation to use these agents holds true whether the patients are at their A1c goals or not. The patient doesn’t need to be on metformin to benefit from these agents. The patient with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure should be taking an SGLT-2 inhibitor.

Chronic kidney disease. Next up, chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urine albumin to creatinine ratio > 30. In that case, the patient should be preferentially on an SGLT-2 inhibitor. Patients not able to take an SGLT-2 for some reason should be prescribed a GLP-1 receptor agonist.

If someone doesn’t fit into that high cardiorenal risk category, then we go to the right side of the algorithm. The goal then is achievement and maintenance of glycemic and weight management goals.

Glycemic management. In choosing medicine for glycemic management, metformin is a reasonable choice. You may need to add another agent to metformin to reach the patient’s glycemic goal. If the patient is far away from goal, then a medication with higher efficacy at lowering glucose might be chosen.

Efficacy is listed as:

- Very high efficacy for glucose lowering: dulaglutide at a high dose, semaglutide, tirzepatide, insulin, or combination injectable agents (GLP-1 receptor agonist/insulin combinations).

- High glucose-lowering efficacy: a GLP-1 receptor agonist not already mentioned, metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones.

- Intermediate glucose lowering efficacy: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

Weight management. For weight management, lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) is important. If lifestyle modification alone is insufficient, consider either a medication that specifically helps with weight management or metabolic surgery.

We particularly want to focus on weight management in patients who have complications from obesity. What would those complications be? Sleep apnea, hip or knee pain from arthritis, back pain – that is, biomechanical complications of obesity or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications for weight loss are listed by degree of efficacy:

- Very high efficacy for weight loss: semaglutide, tirzepatide.

- High efficacy for weight loss: dulaglutide and liraglutide.

- Intermediate for weight loss: GLP-1 receptor agonist (not listed above), SGLT-2 inhibitor.

- Neutral for weight loss: DPP-4 inhibitors and metformin.

Where does insulin fit in? If patients present with a very high A1c, if they are on other medications and their A1c is still not to goal, or if they are catabolic and losing weight because of their diabetes, then insulin has an important place in management.

These are incredibly important guidelines that provide a clear algorithm for a personalized approach to diabetes management.

Dr. Skolnik is professor, department of family medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. He reported conflicts of interest with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Microtox and Mesotox

The terms when they mention one of these terms.

Let’s settle the nomenclature confusion. In this column, I define and outline suggested terminology based on studies and my 15 years of experience using neuromodulators. If any readers or colleagues disagree, please write to me and we can discuss the alternatives in a subsequent article; if you agree, please also write to me so we can collaboratively correct the discrepancies in the literature accordingly.

The term mesotherapy, originating from the Greek “mesos” referring to the early embryonic mesoderm, was identified in the 1950’s by Dr. Michel Pistor, a French physician who administered drugs intradermally. The term was defined as a minimally invasive technique by which drugs or bioactive substances are given in small quantities through dermal micropunctures. Drugs administered intradermally diffuse very slowly and therefore, stay in the tissue longer than those administered intramuscularly.

Thus, Mesotox is defined not by the concentration of the neuromodulator or location, but by the depth of injection in the superficial dermis. It can be delivered through individual injections or through a microneedling pen.

Microtox refers to the dilution of the neuromodulator at concentrations below the proposed dilution guidelines of the manufacturer: Less than 2.5 U per 0.1 mL for onabotulinumtoxinA (OBA), incobotulinumtoxinA (IBA), and prabotulinumtoxinA (PBA); and less than 10 U per 0.1 mL for abobotulinumtoxinA (ABO), This method allows for the injection of superficial cutaneous muscles softening the dynamic rhytids without complete paralysis.

Mesotox is widely used off label for facial lifting, reduction in skin laxity or crepiness, flushing of rosacea, acne, hyperhidrosis of the face, keloids, seborrhea, neck rejuvenation, contouring of the mandibular border, and scalp oiliness. Based on a review of articles using this technique, dilution methods were less than 2.5 U per 1 mL (OBA, IBA) and less than 10 U per 0.1 mL (ABO) depth of injection was the superficial to mid-dermis with injection points 0.5 cm to 1 cm apart.

In a study by Atwa and colleagues, 25 patients with mild facial skin laxity received intradermal Botox-A on one side and saline on the other. This split face study showed a highly significant difference with facial lifting on the treated side. Mesotox injection points vary based on the clinical indication and area being treated.

The treatment of dynamic muscles using standard neuromodulator dosing protocols include the treatment of the glabella, crow’s feet, forehead lines, masseter hypertrophy, bunny lines, gummy smile, perioral lines, mentalis hypertonia, platysmal bands, and marionette lines.

However, hyperdilute neuromodulators or Microtox can effectively be used alone or in combination with standard dosing for the following off-label uses. Used in combination with standard dosing of the forehead lines, I use Microtox in the lateral brow to soften the frontalis muscle without dropping the brow in patients with a low-set brow or lid laxity. I also use it for the jelly roll of the eyes and to open the aperture of the eyes. Along the nose, Microtox can also be used to treat a sagging nasal tip, decrease the width of the ala, and treat overactive facial muscles adjacent to the nose resulting in an overactive nasolabial fold.

Similarly, Microtox can be used to treat lateral smile lines and downward extensions of the crow’s feet. In all of the aforementioned treatment areas, I recommend approximately 0.5-1 U of toxin in each area divided at 1-cm intervals.Mesotox and Microtox are both highly effective strategies to treat the aging face. However, the nomenclature is not interchangeable. I propose that the term Mesotox be used only to articulate or define the superficial injection of a neuromodulator for the improvement of the skin that does not involve the injection into or paralysis of a cutaneous muscle (“tox” being used generically for all neuromodulators). I also propose that the term Microtox should be used to define the dilution of a neuromodulator beyond the manufacturer-recommended dilution protocols – used for the paralysis of a cutaneous muscle. In addition, I recommend that the terms MicroBotox and MesoBotox no longer be used. These procedures all have risks, and adverse events associated with Microtox and Mesotox are similar to those of any neuromodulator injection at FDA-recommended maximum doses, and dilution and storage protocols and proper injection techniques need to be followed. Expertise and training is crucial and treatment by a board-certified dermatologist or plastic surgeon is imperative.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Awaida CJ et al. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Sep;142(3):640-9.

Calvani F et al. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2019 May;27(2):156-61.

Iranmanesh B et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Oct;21(10):4160-70.

Kandhari R et al. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2022 Apr-Jun;15(2):101-7.

Lewandowski M et al. Molecules. 2022 May 13;27(10):3143.

Mammucari M et al. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011 Jun;15(6):682-94.

Park KY et al. Ann Dermatol. 2018 Dec;30(6):688-93.

Pistor M. Chir Dent Fr. 1976;46:59-60.

Rho NK, Gil YC. Toxins (Basel). 2021 Nov 19;13(11):817.

Wu WTL. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):92S-100S.

Zhang H et al. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021 Apr 30;14:407-17.

The terms when they mention one of these terms.

Let’s settle the nomenclature confusion. In this column, I define and outline suggested terminology based on studies and my 15 years of experience using neuromodulators. If any readers or colleagues disagree, please write to me and we can discuss the alternatives in a subsequent article; if you agree, please also write to me so we can collaboratively correct the discrepancies in the literature accordingly.

The term mesotherapy, originating from the Greek “mesos” referring to the early embryonic mesoderm, was identified in the 1950’s by Dr. Michel Pistor, a French physician who administered drugs intradermally. The term was defined as a minimally invasive technique by which drugs or bioactive substances are given in small quantities through dermal micropunctures. Drugs administered intradermally diffuse very slowly and therefore, stay in the tissue longer than those administered intramuscularly.

Thus, Mesotox is defined not by the concentration of the neuromodulator or location, but by the depth of injection in the superficial dermis. It can be delivered through individual injections or through a microneedling pen.

Microtox refers to the dilution of the neuromodulator at concentrations below the proposed dilution guidelines of the manufacturer: Less than 2.5 U per 0.1 mL for onabotulinumtoxinA (OBA), incobotulinumtoxinA (IBA), and prabotulinumtoxinA (PBA); and less than 10 U per 0.1 mL for abobotulinumtoxinA (ABO), This method allows for the injection of superficial cutaneous muscles softening the dynamic rhytids without complete paralysis.

Mesotox is widely used off label for facial lifting, reduction in skin laxity or crepiness, flushing of rosacea, acne, hyperhidrosis of the face, keloids, seborrhea, neck rejuvenation, contouring of the mandibular border, and scalp oiliness. Based on a review of articles using this technique, dilution methods were less than 2.5 U per 1 mL (OBA, IBA) and less than 10 U per 0.1 mL (ABO) depth of injection was the superficial to mid-dermis with injection points 0.5 cm to 1 cm apart.

In a study by Atwa and colleagues, 25 patients with mild facial skin laxity received intradermal Botox-A on one side and saline on the other. This split face study showed a highly significant difference with facial lifting on the treated side. Mesotox injection points vary based on the clinical indication and area being treated.

The treatment of dynamic muscles using standard neuromodulator dosing protocols include the treatment of the glabella, crow’s feet, forehead lines, masseter hypertrophy, bunny lines, gummy smile, perioral lines, mentalis hypertonia, platysmal bands, and marionette lines.

However, hyperdilute neuromodulators or Microtox can effectively be used alone or in combination with standard dosing for the following off-label uses. Used in combination with standard dosing of the forehead lines, I use Microtox in the lateral brow to soften the frontalis muscle without dropping the brow in patients with a low-set brow or lid laxity. I also use it for the jelly roll of the eyes and to open the aperture of the eyes. Along the nose, Microtox can also be used to treat a sagging nasal tip, decrease the width of the ala, and treat overactive facial muscles adjacent to the nose resulting in an overactive nasolabial fold.

Similarly, Microtox can be used to treat lateral smile lines and downward extensions of the crow’s feet. In all of the aforementioned treatment areas, I recommend approximately 0.5-1 U of toxin in each area divided at 1-cm intervals.Mesotox and Microtox are both highly effective strategies to treat the aging face. However, the nomenclature is not interchangeable. I propose that the term Mesotox be used only to articulate or define the superficial injection of a neuromodulator for the improvement of the skin that does not involve the injection into or paralysis of a cutaneous muscle (“tox” being used generically for all neuromodulators). I also propose that the term Microtox should be used to define the dilution of a neuromodulator beyond the manufacturer-recommended dilution protocols – used for the paralysis of a cutaneous muscle. In addition, I recommend that the terms MicroBotox and MesoBotox no longer be used. These procedures all have risks, and adverse events associated with Microtox and Mesotox are similar to those of any neuromodulator injection at FDA-recommended maximum doses, and dilution and storage protocols and proper injection techniques need to be followed. Expertise and training is crucial and treatment by a board-certified dermatologist or plastic surgeon is imperative.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Awaida CJ et al. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Sep;142(3):640-9.

Calvani F et al. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2019 May;27(2):156-61.

Iranmanesh B et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Oct;21(10):4160-70.

Kandhari R et al. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2022 Apr-Jun;15(2):101-7.

Lewandowski M et al. Molecules. 2022 May 13;27(10):3143.

Mammucari M et al. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011 Jun;15(6):682-94.

Park KY et al. Ann Dermatol. 2018 Dec;30(6):688-93.

Pistor M. Chir Dent Fr. 1976;46:59-60.

Rho NK, Gil YC. Toxins (Basel). 2021 Nov 19;13(11):817.

Wu WTL. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):92S-100S.

Zhang H et al. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021 Apr 30;14:407-17.

The terms when they mention one of these terms.

Let’s settle the nomenclature confusion. In this column, I define and outline suggested terminology based on studies and my 15 years of experience using neuromodulators. If any readers or colleagues disagree, please write to me and we can discuss the alternatives in a subsequent article; if you agree, please also write to me so we can collaboratively correct the discrepancies in the literature accordingly.

The term mesotherapy, originating from the Greek “mesos” referring to the early embryonic mesoderm, was identified in the 1950’s by Dr. Michel Pistor, a French physician who administered drugs intradermally. The term was defined as a minimally invasive technique by which drugs or bioactive substances are given in small quantities through dermal micropunctures. Drugs administered intradermally diffuse very slowly and therefore, stay in the tissue longer than those administered intramuscularly.

Thus, Mesotox is defined not by the concentration of the neuromodulator or location, but by the depth of injection in the superficial dermis. It can be delivered through individual injections or through a microneedling pen.

Microtox refers to the dilution of the neuromodulator at concentrations below the proposed dilution guidelines of the manufacturer: Less than 2.5 U per 0.1 mL for onabotulinumtoxinA (OBA), incobotulinumtoxinA (IBA), and prabotulinumtoxinA (PBA); and less than 10 U per 0.1 mL for abobotulinumtoxinA (ABO), This method allows for the injection of superficial cutaneous muscles softening the dynamic rhytids without complete paralysis.

Mesotox is widely used off label for facial lifting, reduction in skin laxity or crepiness, flushing of rosacea, acne, hyperhidrosis of the face, keloids, seborrhea, neck rejuvenation, contouring of the mandibular border, and scalp oiliness. Based on a review of articles using this technique, dilution methods were less than 2.5 U per 1 mL (OBA, IBA) and less than 10 U per 0.1 mL (ABO) depth of injection was the superficial to mid-dermis with injection points 0.5 cm to 1 cm apart.

In a study by Atwa and colleagues, 25 patients with mild facial skin laxity received intradermal Botox-A on one side and saline on the other. This split face study showed a highly significant difference with facial lifting on the treated side. Mesotox injection points vary based on the clinical indication and area being treated.

The treatment of dynamic muscles using standard neuromodulator dosing protocols include the treatment of the glabella, crow’s feet, forehead lines, masseter hypertrophy, bunny lines, gummy smile, perioral lines, mentalis hypertonia, platysmal bands, and marionette lines.

However, hyperdilute neuromodulators or Microtox can effectively be used alone or in combination with standard dosing for the following off-label uses. Used in combination with standard dosing of the forehead lines, I use Microtox in the lateral brow to soften the frontalis muscle without dropping the brow in patients with a low-set brow or lid laxity. I also use it for the jelly roll of the eyes and to open the aperture of the eyes. Along the nose, Microtox can also be used to treat a sagging nasal tip, decrease the width of the ala, and treat overactive facial muscles adjacent to the nose resulting in an overactive nasolabial fold.

Similarly, Microtox can be used to treat lateral smile lines and downward extensions of the crow’s feet. In all of the aforementioned treatment areas, I recommend approximately 0.5-1 U of toxin in each area divided at 1-cm intervals.Mesotox and Microtox are both highly effective strategies to treat the aging face. However, the nomenclature is not interchangeable. I propose that the term Mesotox be used only to articulate or define the superficial injection of a neuromodulator for the improvement of the skin that does not involve the injection into or paralysis of a cutaneous muscle (“tox” being used generically for all neuromodulators). I also propose that the term Microtox should be used to define the dilution of a neuromodulator beyond the manufacturer-recommended dilution protocols – used for the paralysis of a cutaneous muscle. In addition, I recommend that the terms MicroBotox and MesoBotox no longer be used. These procedures all have risks, and adverse events associated with Microtox and Mesotox are similar to those of any neuromodulator injection at FDA-recommended maximum doses, and dilution and storage protocols and proper injection techniques need to be followed. Expertise and training is crucial and treatment by a board-certified dermatologist or plastic surgeon is imperative.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Awaida CJ et al. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Sep;142(3):640-9.

Calvani F et al. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2019 May;27(2):156-61.

Iranmanesh B et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Oct;21(10):4160-70.

Kandhari R et al. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2022 Apr-Jun;15(2):101-7.

Lewandowski M et al. Molecules. 2022 May 13;27(10):3143.

Mammucari M et al. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011 Jun;15(6):682-94.

Park KY et al. Ann Dermatol. 2018 Dec;30(6):688-93.

Pistor M. Chir Dent Fr. 1976;46:59-60.

Rho NK, Gil YC. Toxins (Basel). 2021 Nov 19;13(11):817.

Wu WTL. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):92S-100S.

Zhang H et al. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021 Apr 30;14:407-17.

Ulmus davidiana root extract

Ulmus davidiana, commonly known as yugeunpi, has a long history of use in Korea in treating burns, eczema, frostbite, difficulties in urination, inflammation, and psoriasis,1 and has also been used in China for some of these indications, including skin inflammation.2,3 Currently, there are several areas in which the bioactivity of U. davidiana are under investigation, with numerous potential applications in dermatology. This column focuses briefly on the evidence supporting the traditional uses of the plant and potential new applications.

Anti-inflammatory activity

Eom and colleagues studied the potential of a polysaccharide extract from the root bark of U. davidiana to serve as a suitable cosmetic ingredient for conferring moisturizing, anti-inflammatory, and photoprotective activity. In this 2006 investigation, the composition of the polysaccharide extract was found to be primarily rhamnose, galactose, and glucose. The root extract exhibited a similar humectant moisturizing effect as hyaluronic acid, the researchers reported. The U. davidiana root extract was also found to dose-dependently suppress prostaglandin E2. The inhibition of the release of interleukin-6 and IL-8 was also reported to be significant. The use of the U. davidiana extract also stimulated the recovery of human fibroblasts (two times that of positive control) exposed to UVA irradiation. The researchers suggested that their overall results point to the viability of U. davidiana root extract as a cosmetic agent ingredient to protect skin from UV exposure and the inflammation that follows.2

In 2013, Choi and colleagues found that a methanol extract of the stem and root barks of U. davidiana revealed anti-inflammatory properties, with activity attributed to two trihydroxy acids [then-new trihydroxy fatty acid, 9,12,13-trihydroxyoctadeca-10(Z),15(Z)-dienoic acid, and pinellic acid], both of which blocked prostaglandin D₂ production.4

That same year, Lyu and colleagues studied the antiallergic and anti-inflammatory effects of U. davidiana using a 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB)–induced contact dermatitis mouse model. They found that treatment at a dose of 10 mg/mL successfully prevented skin lesions caused by consistent DNFB application. Further, the researchers observed that topically applied U. davidiana suppressed spongiosis and reduced total serum immunoglobulin and IgG2a levels. Overall, they concluded that the botanical treatment improved contact dermatitis in mice.1