User login

A case-based framework for de-escalating conflict

Hospital medicine can be a demanding and fast-paced environment where resources are stretched thin, with both clinicians and patients stressed. A hospitalist’s role is dynamic, serving as an advocate, leader, or role model while working with interdisciplinary and diverse teams for the welfare of the patient. This constellation of pressures makes a degree of conflict inevitable.

Often, an unexpected scenario can render the hospitalist uncertain and yet the hospitalist’s response can escalate or deescalate conflict. The multiple roles that a hospitalist represents may buckle to the single role of advocating for themselves, a colleague, or a patient in a tense scenario. When this happens, many hospitalists feel disempowered to respond.

De-escalation is a practical skill that involves being calm, respectful, and open minded toward the other person, while also maintaining boundaries. Here we provide case-based tips and skills that highlight the role for de-escalation.

Questions to ask yourself in midst of conflict:

- How did the problematic behavior make you feel?

- What will be your approach in handling this?

- When should you address this?

- What is the outcome you are hoping to achieve?

- What is the outcome the other person is hoping to achieve?

Case 1

There is a female physician rounding with your team. Introductions were made at the start of a patient encounter. The patient repeatedly calls the female physician by her first name and refers to a male colleague as “doctor.”

Commentary: This scenario is commonly encountered by women who are physicians. They may be mistaken for the nurse, a technician, or a housekeeper. This exacerbates inequality and impostor syndrome as women can feel unheard, undervalued, and not recognized for their expertise and achievements. It can be challenging for a woman to reaffirm herself as she worries that the patient will not respect her or will think that she is being aggressive.

Approach: It is vital to interject by firmly reintroducing the female physician by her correct title. If you are the subject of this scenario, you may interject by firmly reintroducing yourself. If the patient or a colleague continues to refer to her by her first name, it is appropriate to say, “Please call her Dr. XYZ.” There is likely another female colleague or trainee nearby that will view this scenario as a model for setting boundaries.

To prevent similar future situations, consistently refer to all peers by their title in front of patients and peers in all professional settings (such as lectures, luncheons, etc.) to establish this as a cultural norm. Also, utilize hospital badges that clearly display roles in large letters.

Case 2

During sign out from a colleague, the colleague repeatedly refers to a patient hospitalized with sickle cell disease as a “frequent flyer” and “drug seeker,” and then remarks, “you know how these patients are.”

Commentary: A situation like this raises concerns about bias and stereotyping. Everyone has implicit bias. Recognizing and acknowledging when implicit bias affects objectivity in patient care is vital to providing appropriate care. It can be intimidating to broach this subject with a colleague as it may cause the colleague to become defensive and uncomfortable as revealing another person’s bias can be difficult. But physicians owe it to a patient’s wellbeing to remain objective and to prevent future colleagues from providing subpar care as a result.

Approach: In this case, saying, “Sometimes my previous experiences can affect my thinking. Will you explain what behaviors the patient has shown this admission that are concerning to you? This will allow me to grasp the complexity of the situation.” Another strategy is to share that there are new recommendations for how to use language about patients with sickle cell disease and patients who require opioids as a part of their treatment plan. Your hospitalist group could have a journal club on how bias affects patients and about the best practices in the care of people with sickle cell disease. A next step could be to build a quality improvement project to review the care of patients hospitalized for sickle cell disease or opioid use.

Case 3

You are conducting bedside rounds with your team. Your intern, a person of color, begins to present. The patient interjects by requesting that the intern leave as he “does not want a foreigner taking care” of him.

Commentary: Requests like this can be shocking. The team leader has a responsibility to immediately act to ensure the psychological safety of the team. Ideally, your response should set firm boundaries and expectations that support the learner as a valued and respected clinician and allow the intern to complete the presentation. In this scenario, regardless of the response the patient takes, it is vital to maintain a safe environment for the trainee. It is crucial to debrief with the team immediately after as an exchange of thoughts and emotions in a safe space can allow for everyone to feel welcome. Additionally, this debrief can provide insights to the team leader of how to address similar situations in the future. The opportunity to allow the intern to no longer follow the patient should be offered, and if the intern opts to no longer follow the patient, accommodations should be made.

Approach: “This physician is a member of the medical team, and we are all working together to provide you with the best care. Everyone on this team is an equal. We value diversity of our team members as it allows us to take care of all our patients. We respect you and expect respect for each member of the team. If you feel that you are unable to respect our team members right now, we will leave for now and return later.” To ensure the patient is provided with appropriate care, be sure to debrief with the patient’s nurse.

Conclusion

These scenarios represent some of the many complex interpersonal challenges hospitalists encounter. These approaches are suggestions that are open to improvement as de-escalation of a conflict is a critical and evolving skill and practice.

For more tips on managing conflict, consider reading “Crucial Conversations” by Kerry Patterson and colleagues. These skills can provide the tools we need to recenter ourselves when we are in the midst of these challenging situations.

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Ashford is assistant professor and program director in the department of internal medicine/pediatrics at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Dr. Lee and Dr. Barrett are based in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. This article is sponsored by the SHM Physicians in Training (PIT) committee, which submits quarterly content to The Hospitalist on topics relevant to trainees and early career hospitalists.

Hospital medicine can be a demanding and fast-paced environment where resources are stretched thin, with both clinicians and patients stressed. A hospitalist’s role is dynamic, serving as an advocate, leader, or role model while working with interdisciplinary and diverse teams for the welfare of the patient. This constellation of pressures makes a degree of conflict inevitable.

Often, an unexpected scenario can render the hospitalist uncertain and yet the hospitalist’s response can escalate or deescalate conflict. The multiple roles that a hospitalist represents may buckle to the single role of advocating for themselves, a colleague, or a patient in a tense scenario. When this happens, many hospitalists feel disempowered to respond.

De-escalation is a practical skill that involves being calm, respectful, and open minded toward the other person, while also maintaining boundaries. Here we provide case-based tips and skills that highlight the role for de-escalation.

Questions to ask yourself in midst of conflict:

- How did the problematic behavior make you feel?

- What will be your approach in handling this?

- When should you address this?

- What is the outcome you are hoping to achieve?

- What is the outcome the other person is hoping to achieve?

Case 1

There is a female physician rounding with your team. Introductions were made at the start of a patient encounter. The patient repeatedly calls the female physician by her first name and refers to a male colleague as “doctor.”

Commentary: This scenario is commonly encountered by women who are physicians. They may be mistaken for the nurse, a technician, or a housekeeper. This exacerbates inequality and impostor syndrome as women can feel unheard, undervalued, and not recognized for their expertise and achievements. It can be challenging for a woman to reaffirm herself as she worries that the patient will not respect her or will think that she is being aggressive.

Approach: It is vital to interject by firmly reintroducing the female physician by her correct title. If you are the subject of this scenario, you may interject by firmly reintroducing yourself. If the patient or a colleague continues to refer to her by her first name, it is appropriate to say, “Please call her Dr. XYZ.” There is likely another female colleague or trainee nearby that will view this scenario as a model for setting boundaries.

To prevent similar future situations, consistently refer to all peers by their title in front of patients and peers in all professional settings (such as lectures, luncheons, etc.) to establish this as a cultural norm. Also, utilize hospital badges that clearly display roles in large letters.

Case 2

During sign out from a colleague, the colleague repeatedly refers to a patient hospitalized with sickle cell disease as a “frequent flyer” and “drug seeker,” and then remarks, “you know how these patients are.”

Commentary: A situation like this raises concerns about bias and stereotyping. Everyone has implicit bias. Recognizing and acknowledging when implicit bias affects objectivity in patient care is vital to providing appropriate care. It can be intimidating to broach this subject with a colleague as it may cause the colleague to become defensive and uncomfortable as revealing another person’s bias can be difficult. But physicians owe it to a patient’s wellbeing to remain objective and to prevent future colleagues from providing subpar care as a result.

Approach: In this case, saying, “Sometimes my previous experiences can affect my thinking. Will you explain what behaviors the patient has shown this admission that are concerning to you? This will allow me to grasp the complexity of the situation.” Another strategy is to share that there are new recommendations for how to use language about patients with sickle cell disease and patients who require opioids as a part of their treatment plan. Your hospitalist group could have a journal club on how bias affects patients and about the best practices in the care of people with sickle cell disease. A next step could be to build a quality improvement project to review the care of patients hospitalized for sickle cell disease or opioid use.

Case 3

You are conducting bedside rounds with your team. Your intern, a person of color, begins to present. The patient interjects by requesting that the intern leave as he “does not want a foreigner taking care” of him.

Commentary: Requests like this can be shocking. The team leader has a responsibility to immediately act to ensure the psychological safety of the team. Ideally, your response should set firm boundaries and expectations that support the learner as a valued and respected clinician and allow the intern to complete the presentation. In this scenario, regardless of the response the patient takes, it is vital to maintain a safe environment for the trainee. It is crucial to debrief with the team immediately after as an exchange of thoughts and emotions in a safe space can allow for everyone to feel welcome. Additionally, this debrief can provide insights to the team leader of how to address similar situations in the future. The opportunity to allow the intern to no longer follow the patient should be offered, and if the intern opts to no longer follow the patient, accommodations should be made.

Approach: “This physician is a member of the medical team, and we are all working together to provide you with the best care. Everyone on this team is an equal. We value diversity of our team members as it allows us to take care of all our patients. We respect you and expect respect for each member of the team. If you feel that you are unable to respect our team members right now, we will leave for now and return later.” To ensure the patient is provided with appropriate care, be sure to debrief with the patient’s nurse.

Conclusion

These scenarios represent some of the many complex interpersonal challenges hospitalists encounter. These approaches are suggestions that are open to improvement as de-escalation of a conflict is a critical and evolving skill and practice.

For more tips on managing conflict, consider reading “Crucial Conversations” by Kerry Patterson and colleagues. These skills can provide the tools we need to recenter ourselves when we are in the midst of these challenging situations.

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Ashford is assistant professor and program director in the department of internal medicine/pediatrics at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Dr. Lee and Dr. Barrett are based in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. This article is sponsored by the SHM Physicians in Training (PIT) committee, which submits quarterly content to The Hospitalist on topics relevant to trainees and early career hospitalists.

Hospital medicine can be a demanding and fast-paced environment where resources are stretched thin, with both clinicians and patients stressed. A hospitalist’s role is dynamic, serving as an advocate, leader, or role model while working with interdisciplinary and diverse teams for the welfare of the patient. This constellation of pressures makes a degree of conflict inevitable.

Often, an unexpected scenario can render the hospitalist uncertain and yet the hospitalist’s response can escalate or deescalate conflict. The multiple roles that a hospitalist represents may buckle to the single role of advocating for themselves, a colleague, or a patient in a tense scenario. When this happens, many hospitalists feel disempowered to respond.

De-escalation is a practical skill that involves being calm, respectful, and open minded toward the other person, while also maintaining boundaries. Here we provide case-based tips and skills that highlight the role for de-escalation.

Questions to ask yourself in midst of conflict:

- How did the problematic behavior make you feel?

- What will be your approach in handling this?

- When should you address this?

- What is the outcome you are hoping to achieve?

- What is the outcome the other person is hoping to achieve?

Case 1

There is a female physician rounding with your team. Introductions were made at the start of a patient encounter. The patient repeatedly calls the female physician by her first name and refers to a male colleague as “doctor.”

Commentary: This scenario is commonly encountered by women who are physicians. They may be mistaken for the nurse, a technician, or a housekeeper. This exacerbates inequality and impostor syndrome as women can feel unheard, undervalued, and not recognized for their expertise and achievements. It can be challenging for a woman to reaffirm herself as she worries that the patient will not respect her or will think that she is being aggressive.

Approach: It is vital to interject by firmly reintroducing the female physician by her correct title. If you are the subject of this scenario, you may interject by firmly reintroducing yourself. If the patient or a colleague continues to refer to her by her first name, it is appropriate to say, “Please call her Dr. XYZ.” There is likely another female colleague or trainee nearby that will view this scenario as a model for setting boundaries.

To prevent similar future situations, consistently refer to all peers by their title in front of patients and peers in all professional settings (such as lectures, luncheons, etc.) to establish this as a cultural norm. Also, utilize hospital badges that clearly display roles in large letters.

Case 2

During sign out from a colleague, the colleague repeatedly refers to a patient hospitalized with sickle cell disease as a “frequent flyer” and “drug seeker,” and then remarks, “you know how these patients are.”

Commentary: A situation like this raises concerns about bias and stereotyping. Everyone has implicit bias. Recognizing and acknowledging when implicit bias affects objectivity in patient care is vital to providing appropriate care. It can be intimidating to broach this subject with a colleague as it may cause the colleague to become defensive and uncomfortable as revealing another person’s bias can be difficult. But physicians owe it to a patient’s wellbeing to remain objective and to prevent future colleagues from providing subpar care as a result.

Approach: In this case, saying, “Sometimes my previous experiences can affect my thinking. Will you explain what behaviors the patient has shown this admission that are concerning to you? This will allow me to grasp the complexity of the situation.” Another strategy is to share that there are new recommendations for how to use language about patients with sickle cell disease and patients who require opioids as a part of their treatment plan. Your hospitalist group could have a journal club on how bias affects patients and about the best practices in the care of people with sickle cell disease. A next step could be to build a quality improvement project to review the care of patients hospitalized for sickle cell disease or opioid use.

Case 3

You are conducting bedside rounds with your team. Your intern, a person of color, begins to present. The patient interjects by requesting that the intern leave as he “does not want a foreigner taking care” of him.

Commentary: Requests like this can be shocking. The team leader has a responsibility to immediately act to ensure the psychological safety of the team. Ideally, your response should set firm boundaries and expectations that support the learner as a valued and respected clinician and allow the intern to complete the presentation. In this scenario, regardless of the response the patient takes, it is vital to maintain a safe environment for the trainee. It is crucial to debrief with the team immediately after as an exchange of thoughts and emotions in a safe space can allow for everyone to feel welcome. Additionally, this debrief can provide insights to the team leader of how to address similar situations in the future. The opportunity to allow the intern to no longer follow the patient should be offered, and if the intern opts to no longer follow the patient, accommodations should be made.

Approach: “This physician is a member of the medical team, and we are all working together to provide you with the best care. Everyone on this team is an equal. We value diversity of our team members as it allows us to take care of all our patients. We respect you and expect respect for each member of the team. If you feel that you are unable to respect our team members right now, we will leave for now and return later.” To ensure the patient is provided with appropriate care, be sure to debrief with the patient’s nurse.

Conclusion

These scenarios represent some of the many complex interpersonal challenges hospitalists encounter. These approaches are suggestions that are open to improvement as de-escalation of a conflict is a critical and evolving skill and practice.

For more tips on managing conflict, consider reading “Crucial Conversations” by Kerry Patterson and colleagues. These skills can provide the tools we need to recenter ourselves when we are in the midst of these challenging situations.

Dr. Rawal is clinical assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Ashford is assistant professor and program director in the department of internal medicine/pediatrics at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Dr. Lee and Dr. Barrett are based in the department of internal medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque. This article is sponsored by the SHM Physicians in Training (PIT) committee, which submits quarterly content to The Hospitalist on topics relevant to trainees and early career hospitalists.

Booster recommendations for pregnant women, teens, and other groups explained

These recommendations have been widened because of the continued emergence of new variants of the virus and the wane of protection over time for both vaccinations and previous disease.

The new recommendations take away some of the questions surrounding eligibility for booster vaccinations while potentially leaving some additional questions. All in all, they provide flexibility for individuals to help protect themselves against the COVID-19 virus, as many are considering celebrating the holidays with friends and family.

The first item that has become clear is that all individuals over 18 are now not only eligible for a booster vaccination a certain time after they have completed their series, but have a recommendation for one.1

But what about a fourth dose? There is a possibility that some patients should be receiving one. For those who require a three-dose series due to a condition that makes them immunocompromised, they should receive their booster vaccination six months after completion of the three-dose series. This distinction may cause confusion for some, but is important for those immunocompromised.

Boosters in women who are pregnant

The recommendations also include specific comments about individuals who are pregnant. Although initial studies did not include pregnant individuals, there has been increasing real world data that vaccination against COVID, including booster vaccinations, is safe and recommended. As pregnancy increases the risk of severe disease if infected by COVID-19, both the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,2 along with other specialty organizations, such as the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, recommend vaccinations for pregnant individuals.

The CDC goes on to describe that there is no evidence of vaccination increasing the risk of infertility. The vaccine protects the pregnant individual and also provides protection to the baby once born. The same is true of breastfeeding individuals.3

I hope that this information allows physicians to feel comfortable recommending vaccinations and boosters to those who are pregnant and breast feeding.

Expanded recommendations for those aged 16-17 years

Recently, the CDC also expanded booster recommendations to include those aged 16-17 years, 6 months after completing their vaccine series.

Those under 18 are currently only able to receive the Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine. This new guidance has left some parents wondering if there will also be approval for booster vaccinations soon for those aged 12-16 who are approaching or have reached six months past the initial vaccine.1

Booster brand for those over 18 years?

Although the recommendation has been simplified for all over age 18 years, there is still a decision to be made about which vaccine to use as the booster.

The recommendations allow individuals to decide which brand of vaccine they would like to have as a booster. They may choose to be vaccinated with the same vaccine they originally received or with a different vaccine. This vaccine flexibility may cause confusion, but ultimately is a good thing as it allows individuals to receive whatever vaccine is available and most convenient. This also allows individuals who have been vaccinated outside of the United States by a different brand of vaccine to also receive a booster vaccination with one of the options available here.

Take home message

Overall, the expansion of booster recommendations will help everyone avoid severe disease from COVID-19 infections. Physicians now have more clarity on who should be receiving these vaccines. Along with testing, masking, and appropriate distancing, these recommendations should help prevent severe disease and death from COVID-19.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, also in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Dec 9.

2. COVID-19 Vaccines and Pregnancy: Conversation Guide. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2021 November.

3. COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Dec 6.

These recommendations have been widened because of the continued emergence of new variants of the virus and the wane of protection over time for both vaccinations and previous disease.

The new recommendations take away some of the questions surrounding eligibility for booster vaccinations while potentially leaving some additional questions. All in all, they provide flexibility for individuals to help protect themselves against the COVID-19 virus, as many are considering celebrating the holidays with friends and family.

The first item that has become clear is that all individuals over 18 are now not only eligible for a booster vaccination a certain time after they have completed their series, but have a recommendation for one.1

But what about a fourth dose? There is a possibility that some patients should be receiving one. For those who require a three-dose series due to a condition that makes them immunocompromised, they should receive their booster vaccination six months after completion of the three-dose series. This distinction may cause confusion for some, but is important for those immunocompromised.

Boosters in women who are pregnant

The recommendations also include specific comments about individuals who are pregnant. Although initial studies did not include pregnant individuals, there has been increasing real world data that vaccination against COVID, including booster vaccinations, is safe and recommended. As pregnancy increases the risk of severe disease if infected by COVID-19, both the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,2 along with other specialty organizations, such as the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, recommend vaccinations for pregnant individuals.

The CDC goes on to describe that there is no evidence of vaccination increasing the risk of infertility. The vaccine protects the pregnant individual and also provides protection to the baby once born. The same is true of breastfeeding individuals.3

I hope that this information allows physicians to feel comfortable recommending vaccinations and boosters to those who are pregnant and breast feeding.

Expanded recommendations for those aged 16-17 years

Recently, the CDC also expanded booster recommendations to include those aged 16-17 years, 6 months after completing their vaccine series.

Those under 18 are currently only able to receive the Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine. This new guidance has left some parents wondering if there will also be approval for booster vaccinations soon for those aged 12-16 who are approaching or have reached six months past the initial vaccine.1

Booster brand for those over 18 years?

Although the recommendation has been simplified for all over age 18 years, there is still a decision to be made about which vaccine to use as the booster.

The recommendations allow individuals to decide which brand of vaccine they would like to have as a booster. They may choose to be vaccinated with the same vaccine they originally received or with a different vaccine. This vaccine flexibility may cause confusion, but ultimately is a good thing as it allows individuals to receive whatever vaccine is available and most convenient. This also allows individuals who have been vaccinated outside of the United States by a different brand of vaccine to also receive a booster vaccination with one of the options available here.

Take home message

Overall, the expansion of booster recommendations will help everyone avoid severe disease from COVID-19 infections. Physicians now have more clarity on who should be receiving these vaccines. Along with testing, masking, and appropriate distancing, these recommendations should help prevent severe disease and death from COVID-19.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, also in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Dec 9.

2. COVID-19 Vaccines and Pregnancy: Conversation Guide. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2021 November.

3. COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Dec 6.

These recommendations have been widened because of the continued emergence of new variants of the virus and the wane of protection over time for both vaccinations and previous disease.

The new recommendations take away some of the questions surrounding eligibility for booster vaccinations while potentially leaving some additional questions. All in all, they provide flexibility for individuals to help protect themselves against the COVID-19 virus, as many are considering celebrating the holidays with friends and family.

The first item that has become clear is that all individuals over 18 are now not only eligible for a booster vaccination a certain time after they have completed their series, but have a recommendation for one.1

But what about a fourth dose? There is a possibility that some patients should be receiving one. For those who require a three-dose series due to a condition that makes them immunocompromised, they should receive their booster vaccination six months after completion of the three-dose series. This distinction may cause confusion for some, but is important for those immunocompromised.

Boosters in women who are pregnant

The recommendations also include specific comments about individuals who are pregnant. Although initial studies did not include pregnant individuals, there has been increasing real world data that vaccination against COVID, including booster vaccinations, is safe and recommended. As pregnancy increases the risk of severe disease if infected by COVID-19, both the CDC and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,2 along with other specialty organizations, such as the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, recommend vaccinations for pregnant individuals.

The CDC goes on to describe that there is no evidence of vaccination increasing the risk of infertility. The vaccine protects the pregnant individual and also provides protection to the baby once born. The same is true of breastfeeding individuals.3

I hope that this information allows physicians to feel comfortable recommending vaccinations and boosters to those who are pregnant and breast feeding.

Expanded recommendations for those aged 16-17 years

Recently, the CDC also expanded booster recommendations to include those aged 16-17 years, 6 months after completing their vaccine series.

Those under 18 are currently only able to receive the Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine. This new guidance has left some parents wondering if there will also be approval for booster vaccinations soon for those aged 12-16 who are approaching or have reached six months past the initial vaccine.1

Booster brand for those over 18 years?

Although the recommendation has been simplified for all over age 18 years, there is still a decision to be made about which vaccine to use as the booster.

The recommendations allow individuals to decide which brand of vaccine they would like to have as a booster. They may choose to be vaccinated with the same vaccine they originally received or with a different vaccine. This vaccine flexibility may cause confusion, but ultimately is a good thing as it allows individuals to receive whatever vaccine is available and most convenient. This also allows individuals who have been vaccinated outside of the United States by a different brand of vaccine to also receive a booster vaccination with one of the options available here.

Take home message

Overall, the expansion of booster recommendations will help everyone avoid severe disease from COVID-19 infections. Physicians now have more clarity on who should be receiving these vaccines. Along with testing, masking, and appropriate distancing, these recommendations should help prevent severe disease and death from COVID-19.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program, also in Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Shots. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Dec 9.

2. COVID-19 Vaccines and Pregnancy: Conversation Guide. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2021 November.

3. COVID-19 Vaccines While Pregnant or Breastfeeding. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Dec 6.

Reflecting on 2021, looking forward to 2022

This month marks the end of my first full calendar year as SHM CEO. Over the years, I have made it a habit to take time to reflect during the month of December, assessing the previous year by reviewing what went well and what could have gone better, and how I can grow and change to meet the needs of future challenges. This reflection sets the stage for my personal and professional “New Year” goals.

This year, 2021, is certainly a year deserving of reflection, and I believe 2022 (and beyond) will need ambitious goals made by dedicated leaders, hospitalists included. Here are my thoughts on what went well in 2021 and what I wish went better – from our greater society to our specialty, to SHM.

Society (as in the larger society)

What went well: Vaccines

There is a lot to be impressed with in 2021, and for me, at the top of that list are the COVID-19 vaccines. I realize the research for mRNA vaccines started more than 20 years ago, and the most successful mRNA vaccine companies have been around for more than a decade, but to roll out a COVID-19 vaccine in less than a year is still just incredible. To take a disease with a 2% mortality rate for someone like myself and effectively reduce that to near zero is something historians will be writing about for years to come.

What I wish went better: Open dialogue

I can’t remember when we stopped listening to each other, and by that, I mean listening to those who do not think exactly like ourselves. As a kid, I was taught to be careful about discussing topics at social events that could go sideways. That usually involved politics, money, or strong beliefs, but wow – now, that list is much longer. Talking about the weather used to be safe, but not anymore. If I were to show pictures of the recent flooding in Annapolis? There would almost certainly be a debate about climate change. At least we can agree on Ted Lasso as a safe topic.

Our specialty

What went well: Hospitalists are vital

There are many, many professions that deserve “hero” status for their part in taming this pandemic: nurses, doctors, emergency medical services, physical therapists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, administrators, and more. But in the doctor category, hospitalists are at the top. Along with our emergency department and intensivist colleagues, hospitalists are one of the pillars of the inpatient response to COVID. More than 3.2 million COVID-19 hospitalizations have occurred, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with numerous state dashboards showing three-quarters of those are cared for on general medical wards, the domain of hospitalists (for example, see my own state of Maryland’s COVID-19 dashboard: https://coronavirus.maryland.gov).

We’ve always had “two patients” – the patient in the bed and the health care system. Many hospitalists have helped their institutions by building COVID care teams, COVID wards, or in the case of Dr. Mindy Kantsiper, building an entire COVID field hospital in a convention center. Without hospitalists, both patients and the system that serves them would have fared much worse in this pandemic. Hospitalists are vital to patients and the health care system. The end. Period. End of story.

What I wish went better: Getting credit

As a profession, we need to be more deliberate about getting credit for the fantastic work we have done to care for COVID-19 patients, as well as inpatients in general. SHM can and must focus more on how to highlight the great work hospitalists have done and will continue to do. A greater understanding by the health care industry – as well as the general public – regarding the important role we play for patient care will help add autonomy in our profession, which in turn adds to resilience during these challenging times.

SHM

What went well: Membership grew

This is the one thing that we at SHM – and I personally – are most proud of. SHM is a membership society; it is the single most important metric for me personally. If physicians aren’t joining, then we are not meeting our core mission to provide value to hospitalists. My sense is the services SHM provides to hospitalists continue to be of value – even during these strenuous times of the pandemic when we had to be physically distant.

Whether it’s our Government Relations Department advocating for hospitalists in Washington, or the Journal of Hospital Medicine, or this very magazine, The Hospitalist, or SHM’s numerous educational offerings, chapter events, and SHM national meetings (Converge, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Leadership Academies, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and more), SHM continues to provide hospitalists with vital tools to help you in your career.

This is also very much a two-way street. If you are reading this, know that without you, our members, our success would not be possible. Your passion and partnership drive us to innovate to meet your needs and those of the patients you serve every day. Thank you for your continued support and inspiration.

What could have gone better: Seeing more of you, in person

This is a tough one for me. Everything I worried about going wrong for SHM in 2021 never materialized. A year ago, my fears for SHM were that membership would shrink, finances would dry up, and the SHM staff would leave (by furlough or by choice). Thankfully, membership grew, our finances are in very good shape for any year, let alone a pandemic year, and the staff have remained at SHM and are engaged and dedicated! SHM even received a “Best Place to Work” award from the Philadelphia Business Journal.

Maybe the one regret I have is that we could not do more in-person events. But even there, I think we did better than most. We had some chapter meetings in person, and the October 2021 Leadership Academy hosted 110 hospitalist leaders, in person, at Amelia Island, Fla. That Leadership Academy went off without a hitch, and the early reviews are superb. I am very optimistic about 2022 in-person events!

Looking forward: 2022 and beyond

I have no illusions that 2022 is going to be easy. I know that the pandemic will not be gone (even though cases are falling nationwide as of this writing), that our nation will struggle with how to deal with polarization, and the workplace will continue to be redefined. Yet, I can’t help but be optimistic.

The pandemic will end eventually; all pandemics do. My hope is that young leaders will step forward to help our nation work through the divisive challenges, and some of those leaders will even be hospitalists! I also know that our profession is more vital than ever, for both patients and the health care system. We’re even getting ready to celebrate SHM’s 25th anniversary, and we can’t wait to revisit our humble beginnings while looking at the bright future of our society and our field.

I am working on my 2022 “New Year” goals, but you can be pretty sure they will revolve around making the world a better place, investing in people, and being ethical and transparent.

Dr. Howell is the CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

This month marks the end of my first full calendar year as SHM CEO. Over the years, I have made it a habit to take time to reflect during the month of December, assessing the previous year by reviewing what went well and what could have gone better, and how I can grow and change to meet the needs of future challenges. This reflection sets the stage for my personal and professional “New Year” goals.

This year, 2021, is certainly a year deserving of reflection, and I believe 2022 (and beyond) will need ambitious goals made by dedicated leaders, hospitalists included. Here are my thoughts on what went well in 2021 and what I wish went better – from our greater society to our specialty, to SHM.

Society (as in the larger society)

What went well: Vaccines

There is a lot to be impressed with in 2021, and for me, at the top of that list are the COVID-19 vaccines. I realize the research for mRNA vaccines started more than 20 years ago, and the most successful mRNA vaccine companies have been around for more than a decade, but to roll out a COVID-19 vaccine in less than a year is still just incredible. To take a disease with a 2% mortality rate for someone like myself and effectively reduce that to near zero is something historians will be writing about for years to come.

What I wish went better: Open dialogue

I can’t remember when we stopped listening to each other, and by that, I mean listening to those who do not think exactly like ourselves. As a kid, I was taught to be careful about discussing topics at social events that could go sideways. That usually involved politics, money, or strong beliefs, but wow – now, that list is much longer. Talking about the weather used to be safe, but not anymore. If I were to show pictures of the recent flooding in Annapolis? There would almost certainly be a debate about climate change. At least we can agree on Ted Lasso as a safe topic.

Our specialty

What went well: Hospitalists are vital

There are many, many professions that deserve “hero” status for their part in taming this pandemic: nurses, doctors, emergency medical services, physical therapists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, administrators, and more. But in the doctor category, hospitalists are at the top. Along with our emergency department and intensivist colleagues, hospitalists are one of the pillars of the inpatient response to COVID. More than 3.2 million COVID-19 hospitalizations have occurred, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with numerous state dashboards showing three-quarters of those are cared for on general medical wards, the domain of hospitalists (for example, see my own state of Maryland’s COVID-19 dashboard: https://coronavirus.maryland.gov).

We’ve always had “two patients” – the patient in the bed and the health care system. Many hospitalists have helped their institutions by building COVID care teams, COVID wards, or in the case of Dr. Mindy Kantsiper, building an entire COVID field hospital in a convention center. Without hospitalists, both patients and the system that serves them would have fared much worse in this pandemic. Hospitalists are vital to patients and the health care system. The end. Period. End of story.

What I wish went better: Getting credit

As a profession, we need to be more deliberate about getting credit for the fantastic work we have done to care for COVID-19 patients, as well as inpatients in general. SHM can and must focus more on how to highlight the great work hospitalists have done and will continue to do. A greater understanding by the health care industry – as well as the general public – regarding the important role we play for patient care will help add autonomy in our profession, which in turn adds to resilience during these challenging times.

SHM

What went well: Membership grew

This is the one thing that we at SHM – and I personally – are most proud of. SHM is a membership society; it is the single most important metric for me personally. If physicians aren’t joining, then we are not meeting our core mission to provide value to hospitalists. My sense is the services SHM provides to hospitalists continue to be of value – even during these strenuous times of the pandemic when we had to be physically distant.

Whether it’s our Government Relations Department advocating for hospitalists in Washington, or the Journal of Hospital Medicine, or this very magazine, The Hospitalist, or SHM’s numerous educational offerings, chapter events, and SHM national meetings (Converge, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Leadership Academies, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and more), SHM continues to provide hospitalists with vital tools to help you in your career.

This is also very much a two-way street. If you are reading this, know that without you, our members, our success would not be possible. Your passion and partnership drive us to innovate to meet your needs and those of the patients you serve every day. Thank you for your continued support and inspiration.

What could have gone better: Seeing more of you, in person

This is a tough one for me. Everything I worried about going wrong for SHM in 2021 never materialized. A year ago, my fears for SHM were that membership would shrink, finances would dry up, and the SHM staff would leave (by furlough or by choice). Thankfully, membership grew, our finances are in very good shape for any year, let alone a pandemic year, and the staff have remained at SHM and are engaged and dedicated! SHM even received a “Best Place to Work” award from the Philadelphia Business Journal.

Maybe the one regret I have is that we could not do more in-person events. But even there, I think we did better than most. We had some chapter meetings in person, and the October 2021 Leadership Academy hosted 110 hospitalist leaders, in person, at Amelia Island, Fla. That Leadership Academy went off without a hitch, and the early reviews are superb. I am very optimistic about 2022 in-person events!

Looking forward: 2022 and beyond

I have no illusions that 2022 is going to be easy. I know that the pandemic will not be gone (even though cases are falling nationwide as of this writing), that our nation will struggle with how to deal with polarization, and the workplace will continue to be redefined. Yet, I can’t help but be optimistic.

The pandemic will end eventually; all pandemics do. My hope is that young leaders will step forward to help our nation work through the divisive challenges, and some of those leaders will even be hospitalists! I also know that our profession is more vital than ever, for both patients and the health care system. We’re even getting ready to celebrate SHM’s 25th anniversary, and we can’t wait to revisit our humble beginnings while looking at the bright future of our society and our field.

I am working on my 2022 “New Year” goals, but you can be pretty sure they will revolve around making the world a better place, investing in people, and being ethical and transparent.

Dr. Howell is the CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

This month marks the end of my first full calendar year as SHM CEO. Over the years, I have made it a habit to take time to reflect during the month of December, assessing the previous year by reviewing what went well and what could have gone better, and how I can grow and change to meet the needs of future challenges. This reflection sets the stage for my personal and professional “New Year” goals.

This year, 2021, is certainly a year deserving of reflection, and I believe 2022 (and beyond) will need ambitious goals made by dedicated leaders, hospitalists included. Here are my thoughts on what went well in 2021 and what I wish went better – from our greater society to our specialty, to SHM.

Society (as in the larger society)

What went well: Vaccines

There is a lot to be impressed with in 2021, and for me, at the top of that list are the COVID-19 vaccines. I realize the research for mRNA vaccines started more than 20 years ago, and the most successful mRNA vaccine companies have been around for more than a decade, but to roll out a COVID-19 vaccine in less than a year is still just incredible. To take a disease with a 2% mortality rate for someone like myself and effectively reduce that to near zero is something historians will be writing about for years to come.

What I wish went better: Open dialogue

I can’t remember when we stopped listening to each other, and by that, I mean listening to those who do not think exactly like ourselves. As a kid, I was taught to be careful about discussing topics at social events that could go sideways. That usually involved politics, money, or strong beliefs, but wow – now, that list is much longer. Talking about the weather used to be safe, but not anymore. If I were to show pictures of the recent flooding in Annapolis? There would almost certainly be a debate about climate change. At least we can agree on Ted Lasso as a safe topic.

Our specialty

What went well: Hospitalists are vital

There are many, many professions that deserve “hero” status for their part in taming this pandemic: nurses, doctors, emergency medical services, physical therapists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, administrators, and more. But in the doctor category, hospitalists are at the top. Along with our emergency department and intensivist colleagues, hospitalists are one of the pillars of the inpatient response to COVID. More than 3.2 million COVID-19 hospitalizations have occurred, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with numerous state dashboards showing three-quarters of those are cared for on general medical wards, the domain of hospitalists (for example, see my own state of Maryland’s COVID-19 dashboard: https://coronavirus.maryland.gov).

We’ve always had “two patients” – the patient in the bed and the health care system. Many hospitalists have helped their institutions by building COVID care teams, COVID wards, or in the case of Dr. Mindy Kantsiper, building an entire COVID field hospital in a convention center. Without hospitalists, both patients and the system that serves them would have fared much worse in this pandemic. Hospitalists are vital to patients and the health care system. The end. Period. End of story.

What I wish went better: Getting credit

As a profession, we need to be more deliberate about getting credit for the fantastic work we have done to care for COVID-19 patients, as well as inpatients in general. SHM can and must focus more on how to highlight the great work hospitalists have done and will continue to do. A greater understanding by the health care industry – as well as the general public – regarding the important role we play for patient care will help add autonomy in our profession, which in turn adds to resilience during these challenging times.

SHM

What went well: Membership grew

This is the one thing that we at SHM – and I personally – are most proud of. SHM is a membership society; it is the single most important metric for me personally. If physicians aren’t joining, then we are not meeting our core mission to provide value to hospitalists. My sense is the services SHM provides to hospitalists continue to be of value – even during these strenuous times of the pandemic when we had to be physically distant.

Whether it’s our Government Relations Department advocating for hospitalists in Washington, or the Journal of Hospital Medicine, or this very magazine, The Hospitalist, or SHM’s numerous educational offerings, chapter events, and SHM national meetings (Converge, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Leadership Academies, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and more), SHM continues to provide hospitalists with vital tools to help you in your career.

This is also very much a two-way street. If you are reading this, know that without you, our members, our success would not be possible. Your passion and partnership drive us to innovate to meet your needs and those of the patients you serve every day. Thank you for your continued support and inspiration.

What could have gone better: Seeing more of you, in person

This is a tough one for me. Everything I worried about going wrong for SHM in 2021 never materialized. A year ago, my fears for SHM were that membership would shrink, finances would dry up, and the SHM staff would leave (by furlough or by choice). Thankfully, membership grew, our finances are in very good shape for any year, let alone a pandemic year, and the staff have remained at SHM and are engaged and dedicated! SHM even received a “Best Place to Work” award from the Philadelphia Business Journal.

Maybe the one regret I have is that we could not do more in-person events. But even there, I think we did better than most. We had some chapter meetings in person, and the October 2021 Leadership Academy hosted 110 hospitalist leaders, in person, at Amelia Island, Fla. That Leadership Academy went off without a hitch, and the early reviews are superb. I am very optimistic about 2022 in-person events!

Looking forward: 2022 and beyond

I have no illusions that 2022 is going to be easy. I know that the pandemic will not be gone (even though cases are falling nationwide as of this writing), that our nation will struggle with how to deal with polarization, and the workplace will continue to be redefined. Yet, I can’t help but be optimistic.

The pandemic will end eventually; all pandemics do. My hope is that young leaders will step forward to help our nation work through the divisive challenges, and some of those leaders will even be hospitalists! I also know that our profession is more vital than ever, for both patients and the health care system. We’re even getting ready to celebrate SHM’s 25th anniversary, and we can’t wait to revisit our humble beginnings while looking at the bright future of our society and our field.

I am working on my 2022 “New Year” goals, but you can be pretty sure they will revolve around making the world a better place, investing in people, and being ethical and transparent.

Dr. Howell is the CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Mumps: Sometimes forgotten but not gone

The 7-year-old boy sat at the edge of a stretcher in the emergency department, looking miserable, as his mother recounted his symptoms to a senior resident physician on duty. Low-grade fever, fatigue, and myalgias prompted rapid SARS-CoV-2 testing at his school. That test, as well as a repeat test at the pediatrician’s office, were negative. A triage protocol in the emergency department prompted a third test, which was also negative.

“Everyone has told me that it’s likely just a different virus,” the mother said. “But then his cheek started to swell. Have you ever seen anything like this?”

The boy turned his head, revealing a diffuse swelling that extended down his right cheek to the angle of his jaw.

“Only in textbooks,” the resident physician responded.

It is a credit to our national immunization program that most practicing clinicians have never actually seen a case of mumps. Before vaccination was introduced in 1967, infection in childhood was nearly universal. Unilateral or bilateral tender swelling of the parotid gland is the typical clinical finding. Low-grade fever, myalgias, decreased appetite, malaise, and headache may precede parotid swelling in some patients. Other patients infected with mumps may have only respiratory symptoms, and some may have no symptoms at all.

Two doses of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine have been recommended for children in the United States since 1989, with the first dose administered at 12-15 months of age. According to data collected through the National Immunization Survey, more than 92% of children in the United States receive at least one dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine by 24 months of age. The vaccine is immunogenic, with 94% of recipients developing measurable mumps antibody (range, 89%-97%). The vaccine has been a public health success: Overall, mumps cases declined more than 99% between 1967 and 2005.

But in the mid-2000s, mumps cases started to rise again, with more than 28,000 reported between 2007 and 2019. Annual cases ranged from 229 to 6,369 and while large, localized outbreaks have contributed to peak years, mumps has been reported from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. According to a recently published paper in Pediatrics, nearly a third of these cases occurred in children <18 years of age and most had been appropriately immunized for age.

Of the 9,172 cases reported in children, 5,461 or 60% occurred between 2015 and 2019. Of these, 55% were in boys. While cases occurred in children of all ages, 54% were in children 11-17 years of age, and 33% were in children 5-10 years of age. Non-Hispanic Asian and/or Pacific Islander children accounted for 38% of cases. Only 2% of cases were associated with international travel and were presumed to have been acquired outside the United States

The reason for the increase in mumps cases in recent years is not well understood. Outbreaks in fully immunized college students have prompted concern about poor B-cell memory after vaccination resulting in waning immunity over time. In the past, antibodies against mumps were boosted by exposure to wild-type mumps virus but such exposures have become fortunately rare for most of us. Cases in recently immunized children suggest there is more to the story. Notably, there is a mismatch between the genotype A mumps virus contained in the current MMR and MMRV vaccines and the genotype G virus currently circulating in the United States.

With the onset of the pandemic and implementation of mitigation measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, circulation of some common respiratory viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus and influenza, was sharply curtailed. Mumps continued to circulate, albeit at reduced levels, with 616 cases reported in 2020. In 2021, 30 states and jurisdictions reported 139 cases through Dec. 1.

Clinicians should suspect mumps in all cases of parotitis, regardless of an individual’s age, vaccination status, or travel history. Laboratory testing is required to distinguish mumps from other infectious and noninfectious causes of parotitis. Infectious causes include gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial infection, as well as other viral infections, including Epstein-Barr virus, coxsackie viruses, parainfluenza, and rarely, influenza. Case reports also describe parotitis coincident with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

When parotitis has been present for 3 days or less, a buccal swab for RT-PCR should be obtained, massaging the parotid gland for 30 seconds before specimen collection. When parotitis has been present for >3 days, a mumps Immunoglobulin M serum antibody should be collected in addition to the buccal swab PCR. A negative IgM does not exclude the possibility of infection, especially in immunized individuals. Mumps is a nationally notifiable disease, and all confirmed and suspect cases should be reported to the state or local health department.

Back in the emergency department, the mother was counseled about the potential diagnosis of mumps and the need for her son to isolate at home for 5 days after the onset of the parotid swelling. She was also educated about potential complications of mumps, including orchitis, aseptic meningitis and encephalitis, and hearing loss. Fortunately, complications are less common in individuals who have been immunized, and orchitis rarely occurs in prepubertal boys.

The resident physician also confirmed that other members of the household had been appropriately immunized for age. While the MMR vaccine does not prevent illness in those already infected with mumps and is not indicated as postexposure prophylaxis, providing vaccine to those not already immunized can protect against future exposures. A third dose of MMR vaccine is only indicated in the setting of an outbreak and when specifically recommended by public health authorities for those deemed to be in a high-risk group. Additional information about mumps is available at www.cdc.gov/mumps/hcp.html#report.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The 7-year-old boy sat at the edge of a stretcher in the emergency department, looking miserable, as his mother recounted his symptoms to a senior resident physician on duty. Low-grade fever, fatigue, and myalgias prompted rapid SARS-CoV-2 testing at his school. That test, as well as a repeat test at the pediatrician’s office, were negative. A triage protocol in the emergency department prompted a third test, which was also negative.

“Everyone has told me that it’s likely just a different virus,” the mother said. “But then his cheek started to swell. Have you ever seen anything like this?”

The boy turned his head, revealing a diffuse swelling that extended down his right cheek to the angle of his jaw.

“Only in textbooks,” the resident physician responded.

It is a credit to our national immunization program that most practicing clinicians have never actually seen a case of mumps. Before vaccination was introduced in 1967, infection in childhood was nearly universal. Unilateral or bilateral tender swelling of the parotid gland is the typical clinical finding. Low-grade fever, myalgias, decreased appetite, malaise, and headache may precede parotid swelling in some patients. Other patients infected with mumps may have only respiratory symptoms, and some may have no symptoms at all.

Two doses of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine have been recommended for children in the United States since 1989, with the first dose administered at 12-15 months of age. According to data collected through the National Immunization Survey, more than 92% of children in the United States receive at least one dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine by 24 months of age. The vaccine is immunogenic, with 94% of recipients developing measurable mumps antibody (range, 89%-97%). The vaccine has been a public health success: Overall, mumps cases declined more than 99% between 1967 and 2005.

But in the mid-2000s, mumps cases started to rise again, with more than 28,000 reported between 2007 and 2019. Annual cases ranged from 229 to 6,369 and while large, localized outbreaks have contributed to peak years, mumps has been reported from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. According to a recently published paper in Pediatrics, nearly a third of these cases occurred in children <18 years of age and most had been appropriately immunized for age.

Of the 9,172 cases reported in children, 5,461 or 60% occurred between 2015 and 2019. Of these, 55% were in boys. While cases occurred in children of all ages, 54% were in children 11-17 years of age, and 33% were in children 5-10 years of age. Non-Hispanic Asian and/or Pacific Islander children accounted for 38% of cases. Only 2% of cases were associated with international travel and were presumed to have been acquired outside the United States

The reason for the increase in mumps cases in recent years is not well understood. Outbreaks in fully immunized college students have prompted concern about poor B-cell memory after vaccination resulting in waning immunity over time. In the past, antibodies against mumps were boosted by exposure to wild-type mumps virus but such exposures have become fortunately rare for most of us. Cases in recently immunized children suggest there is more to the story. Notably, there is a mismatch between the genotype A mumps virus contained in the current MMR and MMRV vaccines and the genotype G virus currently circulating in the United States.

With the onset of the pandemic and implementation of mitigation measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, circulation of some common respiratory viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus and influenza, was sharply curtailed. Mumps continued to circulate, albeit at reduced levels, with 616 cases reported in 2020. In 2021, 30 states and jurisdictions reported 139 cases through Dec. 1.

Clinicians should suspect mumps in all cases of parotitis, regardless of an individual’s age, vaccination status, or travel history. Laboratory testing is required to distinguish mumps from other infectious and noninfectious causes of parotitis. Infectious causes include gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial infection, as well as other viral infections, including Epstein-Barr virus, coxsackie viruses, parainfluenza, and rarely, influenza. Case reports also describe parotitis coincident with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

When parotitis has been present for 3 days or less, a buccal swab for RT-PCR should be obtained, massaging the parotid gland for 30 seconds before specimen collection. When parotitis has been present for >3 days, a mumps Immunoglobulin M serum antibody should be collected in addition to the buccal swab PCR. A negative IgM does not exclude the possibility of infection, especially in immunized individuals. Mumps is a nationally notifiable disease, and all confirmed and suspect cases should be reported to the state or local health department.

Back in the emergency department, the mother was counseled about the potential diagnosis of mumps and the need for her son to isolate at home for 5 days after the onset of the parotid swelling. She was also educated about potential complications of mumps, including orchitis, aseptic meningitis and encephalitis, and hearing loss. Fortunately, complications are less common in individuals who have been immunized, and orchitis rarely occurs in prepubertal boys.

The resident physician also confirmed that other members of the household had been appropriately immunized for age. While the MMR vaccine does not prevent illness in those already infected with mumps and is not indicated as postexposure prophylaxis, providing vaccine to those not already immunized can protect against future exposures. A third dose of MMR vaccine is only indicated in the setting of an outbreak and when specifically recommended by public health authorities for those deemed to be in a high-risk group. Additional information about mumps is available at www.cdc.gov/mumps/hcp.html#report.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The 7-year-old boy sat at the edge of a stretcher in the emergency department, looking miserable, as his mother recounted his symptoms to a senior resident physician on duty. Low-grade fever, fatigue, and myalgias prompted rapid SARS-CoV-2 testing at his school. That test, as well as a repeat test at the pediatrician’s office, were negative. A triage protocol in the emergency department prompted a third test, which was also negative.

“Everyone has told me that it’s likely just a different virus,” the mother said. “But then his cheek started to swell. Have you ever seen anything like this?”

The boy turned his head, revealing a diffuse swelling that extended down his right cheek to the angle of his jaw.

“Only in textbooks,” the resident physician responded.

It is a credit to our national immunization program that most practicing clinicians have never actually seen a case of mumps. Before vaccination was introduced in 1967, infection in childhood was nearly universal. Unilateral or bilateral tender swelling of the parotid gland is the typical clinical finding. Low-grade fever, myalgias, decreased appetite, malaise, and headache may precede parotid swelling in some patients. Other patients infected with mumps may have only respiratory symptoms, and some may have no symptoms at all.

Two doses of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine have been recommended for children in the United States since 1989, with the first dose administered at 12-15 months of age. According to data collected through the National Immunization Survey, more than 92% of children in the United States receive at least one dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine by 24 months of age. The vaccine is immunogenic, with 94% of recipients developing measurable mumps antibody (range, 89%-97%). The vaccine has been a public health success: Overall, mumps cases declined more than 99% between 1967 and 2005.

But in the mid-2000s, mumps cases started to rise again, with more than 28,000 reported between 2007 and 2019. Annual cases ranged from 229 to 6,369 and while large, localized outbreaks have contributed to peak years, mumps has been reported from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. According to a recently published paper in Pediatrics, nearly a third of these cases occurred in children <18 years of age and most had been appropriately immunized for age.

Of the 9,172 cases reported in children, 5,461 or 60% occurred between 2015 and 2019. Of these, 55% were in boys. While cases occurred in children of all ages, 54% were in children 11-17 years of age, and 33% were in children 5-10 years of age. Non-Hispanic Asian and/or Pacific Islander children accounted for 38% of cases. Only 2% of cases were associated with international travel and were presumed to have been acquired outside the United States

The reason for the increase in mumps cases in recent years is not well understood. Outbreaks in fully immunized college students have prompted concern about poor B-cell memory after vaccination resulting in waning immunity over time. In the past, antibodies against mumps were boosted by exposure to wild-type mumps virus but such exposures have become fortunately rare for most of us. Cases in recently immunized children suggest there is more to the story. Notably, there is a mismatch between the genotype A mumps virus contained in the current MMR and MMRV vaccines and the genotype G virus currently circulating in the United States.

With the onset of the pandemic and implementation of mitigation measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, circulation of some common respiratory viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus and influenza, was sharply curtailed. Mumps continued to circulate, albeit at reduced levels, with 616 cases reported in 2020. In 2021, 30 states and jurisdictions reported 139 cases through Dec. 1.

Clinicians should suspect mumps in all cases of parotitis, regardless of an individual’s age, vaccination status, or travel history. Laboratory testing is required to distinguish mumps from other infectious and noninfectious causes of parotitis. Infectious causes include gram-positive and gram-negative bacterial infection, as well as other viral infections, including Epstein-Barr virus, coxsackie viruses, parainfluenza, and rarely, influenza. Case reports also describe parotitis coincident with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

When parotitis has been present for 3 days or less, a buccal swab for RT-PCR should be obtained, massaging the parotid gland for 30 seconds before specimen collection. When parotitis has been present for >3 days, a mumps Immunoglobulin M serum antibody should be collected in addition to the buccal swab PCR. A negative IgM does not exclude the possibility of infection, especially in immunized individuals. Mumps is a nationally notifiable disease, and all confirmed and suspect cases should be reported to the state or local health department.

Back in the emergency department, the mother was counseled about the potential diagnosis of mumps and the need for her son to isolate at home for 5 days after the onset of the parotid swelling. She was also educated about potential complications of mumps, including orchitis, aseptic meningitis and encephalitis, and hearing loss. Fortunately, complications are less common in individuals who have been immunized, and orchitis rarely occurs in prepubertal boys.

The resident physician also confirmed that other members of the household had been appropriately immunized for age. While the MMR vaccine does not prevent illness in those already infected with mumps and is not indicated as postexposure prophylaxis, providing vaccine to those not already immunized can protect against future exposures. A third dose of MMR vaccine is only indicated in the setting of an outbreak and when specifically recommended by public health authorities for those deemed to be in a high-risk group. Additional information about mumps is available at www.cdc.gov/mumps/hcp.html#report.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

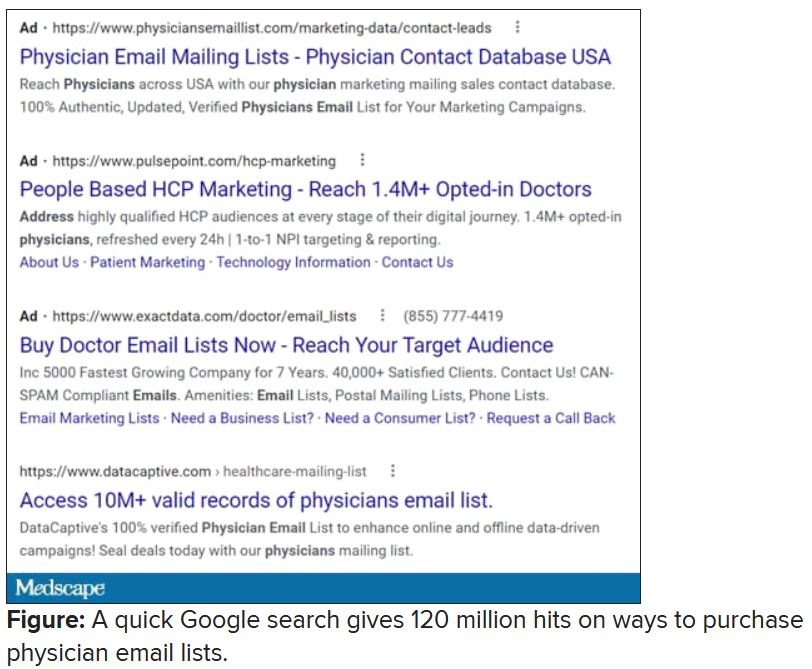

Spam filter failure: Selling physician emails equals big $$

Despite the best efforts of my institution’s spam filter, I’ve realized that I spend at least 4 minutes every day of the week removing junk email from my in basket: EMR vendors, predatory journals trying to lure me into paying their outrageous publication fees, people who want to help me with my billing software (evidently that .edu extension hasn’t clicked for them yet), headhunters trying to fill specialty positions in other states, market researchers offering a gift card for 40 minutes filling out a survey.

If you do the math, 4 minutes daily is 1,460 minutes per year. That’s an entire day of my life lost each year to this useless nonsense, which I never agreed to receive in the first place. Now multiply that by the 22 million health care workers in the United States, or even just by the 985,000 licensed physicians in this country. Then factor in the $638 per hour in gross revenue generated by the average primary care physician, as a conservative, well-documented value.

By my reckoning, these bozos owe the United States alone over $15 billion in lost GDP each year.

So why don’t we shut it down!? The CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 attempted to at least mitigate the problem. It applies only to commercial entities (I know, I’d love to report some political groups, too). To avoid violating the law and risking fines of up to $16,000 per individual email, senders must:

- Not use misleading header info (including domain name and email address)

- Not use deceptive subject lines

- Clearly label the email as an ad

- Give an actual physical address of the sender

- Tell recipients how to opt out of future emails

- Honor opt-out requests within 10 business days

- Monitor the activities of any subcontractor sending email on their behalf

I can say with certainty that much of the trash in my inbox violates at least one of these. But that doesn’t matter if there is not an efficient way to report the violators and ensure that they’ll be tracked down. Hard enough if they live here, impossible if the email is routed from overseas, as much of it clearly is.

If you receive email in violation of the act, experts recommend that you write down the email address and the business name of the sender, fill out a complaint form on the Federal Trade Commission website, or send an email to spam@uce.gov, then send an email to your Internet service provider’s abuse desk. If you’re not working within a big institution like mine that has hot and cold running IT personnel that operate their own abuse prevention office, the address you’ll need is likely abuse@domain_name or postmaster@domain_name. Just hitting the spam button at the top of your browser/email software may do the trick. There’s more good advice at the FTC’s consumer spam page.

The answer came, ironically, to my email inbox in the form of one of those emails that did indeed violate the law.

I rolled my eyes and started into my reporting subroutine but then stopped cold. Just 1 second. If this person is selling lists of email addresses of conference attendees, somebody within the conference structure must be providing them. How is that legal? I have never agreed, in registering for a medical conference, to allow them to share my email address with anyone. To think that they are making money from that is extremely galling.

Vermont, at least, has enacted a law requiring companies that traffic in such email lists to register with the state. Although it has been in effect for 2 years, the jury is out regarding its efficacy. Our European counterparts are protected by the General Data Protection Regulation, which specifies that commercial email can be sent only to individuals who have explicitly opted into such mailings, and that purchased email lists are not compliant with the requirement.

Anybody have the inside scoop on this? Can we demand that our professional societies safeguard their attendee databases so this won’t happen? If they won’t, why am I paying big money to attend their conferences, only for them to make even more money at my expense?

Dr. Hitchcock is assistant professor, department of radiation oncology, at the University of Florida, Gainesville. She reported receiving research grant money from Merck. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.