User login

State of Confusion: Should All Children Get Lipid Labs for High Cholesterol?

Clinicians receive conflicting advice on whether to order blood tests to screen for lipids in children. A new study could add to the confusion. Researchers found that a combination of physical proxy measures such as hypertension and body mass index (BMI) predicted the risk for future cardiovascular events as well as the physical model plus lipid labs, questioning the value of those blood tests.

Some medical organizations advise screening only for high-risk children because more research is needed to define the harms and benefits of universal screening. Diet and behavioral changes are sufficient for most children, and universal screening could lead to false positives and unnecessary further testing, they said.

Groups that favor lipid tests for all children say these measurements detect familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) that would not otherwise be diagnosed, leading to treatment with drugs like statins and a greater chance of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adulthood.

Researchers from the new study said their findings do not address screenings for FH, which affects 1 in 250 US children and puts them at a risk for atherosclerotic CVD.

Recommending Blood Tests in Age Groups

One of the seminal guidelines on screening lipids in children came from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which in 2011 recommended children undergo dyslipidemia screening between the ages of 9 and 11 years and again between 17 and 21 years. Children should receive a screening starting at age 2 years if they have a family history of CVD or dyslipidemia or have diabetes, an elevated BMI, or hypertension. The American Academy of Pediatrics shortly followed suit, issuing similar recommendations.

Screening for the two subsets of ages was an expansion from the original 1992 guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program, which recommended screening only for children with either a family history of early CVD or elevated total cholesterol levels.

A 2011 panel for the NHLBI said the older approach identified significantly fewer children with abnormal levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) than the addition of two age groups for screening, adding that many children do not have a complete family history. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association later supported NHLBI’s stance in their joint guidelines on the management of cholesterol.

Mark Corkins, MD, chair of the AAP’s Committee on Nutrition, told Medscape Medical News that if children are screened only because they have obesity or a family history of FH, some with elevated lipid levels will be missed. For instance, studies indicate caregiver recall of FH often is inaccurate, and the genetic disorder that causes the condition is not related to obesity.

“The screening is to find familial hypercholesterolemia, to try to find the ones that need therapy,” that would not be caught by the risk-based screening earlier on in childhood, Corkins said.

Only Screen Children With Risk Factors

But other groups do not agree. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening for lipid disorders in asymptomatic children and teens.

The group also said it found inadequate evidence that lipid-lowering interventions in the general pediatric population lead to reductions in cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality once they reached adulthood. USPSTF also raised questions about the safety of lipid-lowering drugs in children.

“The current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for lipid disorders in children and adolescents 20 years or younger,” the panel wrote.

The American Academy of Family Physicians supports USPSTF’s recommendations.

Low Rate of Screening

While the uncertainty over screening in children continues, the practice has been adopted by a minority of clinicians.

A study published in JAMA Network Open in July found 9% of 700,000 9- to 11-year-olds had a documented result from a lipid screening. Among more than 1.3 million 17- to 21-year-olds, 13% had received a screening.

As BMI went up, so did screening rates. A little over 9% children and teens with a healthy weight were screened compared with 14.7% of those with moderate obesity and 21.9% of those with severe obesity.

Among those screened, 32.3% of 9- to 11-year-olds and 30.2% of 17- to 21-year-olds had abnormal lipid levels, defined as having one elevated measure out of five, including total cholesterol of 200 mg/dL or higher or LDL-C levels of 130 mg/dL or higher.

Justin Zachariah, MD, MPH, an associate professor of pediatrics-cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, spoke about physicians screening children based only on factors like obesity during a presentation at the recent annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. He cited research showing roughly one in four children with abnormal lipids had a normal weight.

If a clinician is reserving a lipid screening for a child who is overweight or has obesity, “you’re missing nearly half the problem,” Zachariah said during his presentation.

One reason for the low rate of universal screening may be inattention to FH by clinicians, according to Samuel S. Gidding, MD, a professor in the Department of Genomic Health at Geisinger College of Health Sciences in Bridgewater Corners, Vermont.

For instance, a clinician has only a set amount of time during a well-child visit and other issues may take precedence, “so it doesn’t make sense to broach preventive screening for something that could happen 30 or 40 years from now, vs this [other] very immediate problem,” he said.

Clinicians “are triggered to act on the LDL level, but don’t think about FH as a possible diagnosis,” Gidding told Medscape Medical News.

Another barrier is that in some settings, caregivers must take children and teens to another facility on a different day to fulfill an order for a lipid test.

“It’s reluctance of doctors to order it, knowing patients won’t go through with it,” Gidding said.

Gidding is a consultant for Esperion Therapeutics. Other sources in this story reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians receive conflicting advice on whether to order blood tests to screen for lipids in children. A new study could add to the confusion. Researchers found that a combination of physical proxy measures such as hypertension and body mass index (BMI) predicted the risk for future cardiovascular events as well as the physical model plus lipid labs, questioning the value of those blood tests.

Some medical organizations advise screening only for high-risk children because more research is needed to define the harms and benefits of universal screening. Diet and behavioral changes are sufficient for most children, and universal screening could lead to false positives and unnecessary further testing, they said.

Groups that favor lipid tests for all children say these measurements detect familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) that would not otherwise be diagnosed, leading to treatment with drugs like statins and a greater chance of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adulthood.

Researchers from the new study said their findings do not address screenings for FH, which affects 1 in 250 US children and puts them at a risk for atherosclerotic CVD.

Recommending Blood Tests in Age Groups

One of the seminal guidelines on screening lipids in children came from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which in 2011 recommended children undergo dyslipidemia screening between the ages of 9 and 11 years and again between 17 and 21 years. Children should receive a screening starting at age 2 years if they have a family history of CVD or dyslipidemia or have diabetes, an elevated BMI, or hypertension. The American Academy of Pediatrics shortly followed suit, issuing similar recommendations.

Screening for the two subsets of ages was an expansion from the original 1992 guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program, which recommended screening only for children with either a family history of early CVD or elevated total cholesterol levels.

A 2011 panel for the NHLBI said the older approach identified significantly fewer children with abnormal levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) than the addition of two age groups for screening, adding that many children do not have a complete family history. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association later supported NHLBI’s stance in their joint guidelines on the management of cholesterol.

Mark Corkins, MD, chair of the AAP’s Committee on Nutrition, told Medscape Medical News that if children are screened only because they have obesity or a family history of FH, some with elevated lipid levels will be missed. For instance, studies indicate caregiver recall of FH often is inaccurate, and the genetic disorder that causes the condition is not related to obesity.

“The screening is to find familial hypercholesterolemia, to try to find the ones that need therapy,” that would not be caught by the risk-based screening earlier on in childhood, Corkins said.

Only Screen Children With Risk Factors

But other groups do not agree. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening for lipid disorders in asymptomatic children and teens.

The group also said it found inadequate evidence that lipid-lowering interventions in the general pediatric population lead to reductions in cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality once they reached adulthood. USPSTF also raised questions about the safety of lipid-lowering drugs in children.

“The current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for lipid disorders in children and adolescents 20 years or younger,” the panel wrote.

The American Academy of Family Physicians supports USPSTF’s recommendations.

Low Rate of Screening

While the uncertainty over screening in children continues, the practice has been adopted by a minority of clinicians.

A study published in JAMA Network Open in July found 9% of 700,000 9- to 11-year-olds had a documented result from a lipid screening. Among more than 1.3 million 17- to 21-year-olds, 13% had received a screening.

As BMI went up, so did screening rates. A little over 9% children and teens with a healthy weight were screened compared with 14.7% of those with moderate obesity and 21.9% of those with severe obesity.

Among those screened, 32.3% of 9- to 11-year-olds and 30.2% of 17- to 21-year-olds had abnormal lipid levels, defined as having one elevated measure out of five, including total cholesterol of 200 mg/dL or higher or LDL-C levels of 130 mg/dL or higher.

Justin Zachariah, MD, MPH, an associate professor of pediatrics-cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, spoke about physicians screening children based only on factors like obesity during a presentation at the recent annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. He cited research showing roughly one in four children with abnormal lipids had a normal weight.

If a clinician is reserving a lipid screening for a child who is overweight or has obesity, “you’re missing nearly half the problem,” Zachariah said during his presentation.

One reason for the low rate of universal screening may be inattention to FH by clinicians, according to Samuel S. Gidding, MD, a professor in the Department of Genomic Health at Geisinger College of Health Sciences in Bridgewater Corners, Vermont.

For instance, a clinician has only a set amount of time during a well-child visit and other issues may take precedence, “so it doesn’t make sense to broach preventive screening for something that could happen 30 or 40 years from now, vs this [other] very immediate problem,” he said.

Clinicians “are triggered to act on the LDL level, but don’t think about FH as a possible diagnosis,” Gidding told Medscape Medical News.

Another barrier is that in some settings, caregivers must take children and teens to another facility on a different day to fulfill an order for a lipid test.

“It’s reluctance of doctors to order it, knowing patients won’t go through with it,” Gidding said.

Gidding is a consultant for Esperion Therapeutics. Other sources in this story reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians receive conflicting advice on whether to order blood tests to screen for lipids in children. A new study could add to the confusion. Researchers found that a combination of physical proxy measures such as hypertension and body mass index (BMI) predicted the risk for future cardiovascular events as well as the physical model plus lipid labs, questioning the value of those blood tests.

Some medical organizations advise screening only for high-risk children because more research is needed to define the harms and benefits of universal screening. Diet and behavioral changes are sufficient for most children, and universal screening could lead to false positives and unnecessary further testing, they said.

Groups that favor lipid tests for all children say these measurements detect familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) that would not otherwise be diagnosed, leading to treatment with drugs like statins and a greater chance of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adulthood.

Researchers from the new study said their findings do not address screenings for FH, which affects 1 in 250 US children and puts them at a risk for atherosclerotic CVD.

Recommending Blood Tests in Age Groups

One of the seminal guidelines on screening lipids in children came from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which in 2011 recommended children undergo dyslipidemia screening between the ages of 9 and 11 years and again between 17 and 21 years. Children should receive a screening starting at age 2 years if they have a family history of CVD or dyslipidemia or have diabetes, an elevated BMI, or hypertension. The American Academy of Pediatrics shortly followed suit, issuing similar recommendations.

Screening for the two subsets of ages was an expansion from the original 1992 guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program, which recommended screening only for children with either a family history of early CVD or elevated total cholesterol levels.

A 2011 panel for the NHLBI said the older approach identified significantly fewer children with abnormal levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) than the addition of two age groups for screening, adding that many children do not have a complete family history. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association later supported NHLBI’s stance in their joint guidelines on the management of cholesterol.

Mark Corkins, MD, chair of the AAP’s Committee on Nutrition, told Medscape Medical News that if children are screened only because they have obesity or a family history of FH, some with elevated lipid levels will be missed. For instance, studies indicate caregiver recall of FH often is inaccurate, and the genetic disorder that causes the condition is not related to obesity.

“The screening is to find familial hypercholesterolemia, to try to find the ones that need therapy,” that would not be caught by the risk-based screening earlier on in childhood, Corkins said.

Only Screen Children With Risk Factors

But other groups do not agree. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening for lipid disorders in asymptomatic children and teens.

The group also said it found inadequate evidence that lipid-lowering interventions in the general pediatric population lead to reductions in cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality once they reached adulthood. USPSTF also raised questions about the safety of lipid-lowering drugs in children.

“The current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for lipid disorders in children and adolescents 20 years or younger,” the panel wrote.

The American Academy of Family Physicians supports USPSTF’s recommendations.

Low Rate of Screening

While the uncertainty over screening in children continues, the practice has been adopted by a minority of clinicians.

A study published in JAMA Network Open in July found 9% of 700,000 9- to 11-year-olds had a documented result from a lipid screening. Among more than 1.3 million 17- to 21-year-olds, 13% had received a screening.

As BMI went up, so did screening rates. A little over 9% children and teens with a healthy weight were screened compared with 14.7% of those with moderate obesity and 21.9% of those with severe obesity.

Among those screened, 32.3% of 9- to 11-year-olds and 30.2% of 17- to 21-year-olds had abnormal lipid levels, defined as having one elevated measure out of five, including total cholesterol of 200 mg/dL or higher or LDL-C levels of 130 mg/dL or higher.

Justin Zachariah, MD, MPH, an associate professor of pediatrics-cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, spoke about physicians screening children based only on factors like obesity during a presentation at the recent annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. He cited research showing roughly one in four children with abnormal lipids had a normal weight.

If a clinician is reserving a lipid screening for a child who is overweight or has obesity, “you’re missing nearly half the problem,” Zachariah said during his presentation.

One reason for the low rate of universal screening may be inattention to FH by clinicians, according to Samuel S. Gidding, MD, a professor in the Department of Genomic Health at Geisinger College of Health Sciences in Bridgewater Corners, Vermont.

For instance, a clinician has only a set amount of time during a well-child visit and other issues may take precedence, “so it doesn’t make sense to broach preventive screening for something that could happen 30 or 40 years from now, vs this [other] very immediate problem,” he said.

Clinicians “are triggered to act on the LDL level, but don’t think about FH as a possible diagnosis,” Gidding told Medscape Medical News.

Another barrier is that in some settings, caregivers must take children and teens to another facility on a different day to fulfill an order for a lipid test.

“It’s reluctance of doctors to order it, knowing patients won’t go through with it,” Gidding said.

Gidding is a consultant for Esperion Therapeutics. Other sources in this story reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AHA Scientific Statement Links Three Common Cardiovascular Diseases to Cognitive Decline, Dementia

The statement includes an extensive research review and offers compelling evidence of the inextricable link between heart health and brain health, which investigators said underscores the benefit of early intervention.

The cumulative evidence “confirms that the trajectories of cardiac health and brain health are inextricably intertwined through modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote.

Investigators say the findings reinforce the message that addressing cardiovascular health early in life may deter the onset or progression of cognitive impairment later on.

And the earlier this is done, the better, said lead author Fernando D. Testai, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology and the vascular neurology section head, Department of Neurology and Rehabilitation, University of Illinois, Chicago.

The statement was published online in Stroke.

Bridging the Research Gap

It’s well known that there’s a bidirectional relationship between heart and brain function. For example, heart failure can lead to decreased blood flow that can damage the brain, and stroke in some areas of the brain can affect the heart.

However, that’s only part of the puzzle and doesn’t address all the gaps in the understanding of how cardiovascular disease contributes to cognition, said Testai.

“What we’re trying to do here is to go one step further and describe other connections between the heart and the brain,” he said.

Investigators carried out an extensive PubMed search for heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and coronary heart disease. Researchers detailed the frequency of each condition, mechanisms by which they might cause cognitive impairment, and prospects for prevention and treatment to maintain brain health.

A recurring theme in the paper is the role of inflammation. Evidence shows there are “remarkable similarities in the inflammatory response that takes place,” with both cardiac disease and cognitive decline, said Testai.

Another potential shared mechanism relates to biomarkers, particularly amyloid, which is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

“But some studies show amyloid can also be present in the heart, especially in patients who have decreased ejection fraction,” said Testai.

Robust Heart-Brain Connection

The statement’s authors collected a substantial amount of evidence showing vascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes “can change how the brain processes and clears up amyloid,” Testai added.

The paper also provides a compilation of evidence of shared genetic predispositions when it comes to heart and brain disorders.

“We noticed that some genetic signatures that have historically been associated with heart disease seem to also correlate with structural changes in the brain. That means that at the end of the day, some patients may be born with a genetic predisposition to developing both conditions,” said Testai.

This indicates that the link between the two organs “begins as early as conception” and underscores the importance of adopting healthy lifestyle habits as early as possible, he added.

“That means you can avoid bad habits that eventually lead to hypertension, diabetes, and cholesterol, that eventually will lead to cardiac disease, which eventually will lead to stroke, which eventually will lead to cognitive decline,” Testai noted.

However, cardiovascular health is more complicated than having good genes and adhering to a healthy lifestyle. It’s not clear, for example, why some people who should be predisposed to developing heart disease do not develop it, something Testai refers to as enhanced “resilience.”

For example, Hispanic or Latino patients, who have relatively poor cardiovascular risk factor profiles, seem to be less susceptible to developing cardiac disease.

More Research Needed

While genetics may partly explain the paradox, Testai believes other protective factors are at play, including strong social support networks.

Testai referred to the AHA’s “Life’s Essential 8” — the eight components of cardiovascular health. These include a healthy diet, participation in physical activity, nicotine avoidance, healthy sleep, healthy weight, and healthy levels of blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure.

More evidence is needed to show that effective management of cardiac disease positively affects cognition. Currently, cognitive measures are rarely included in studies examining various heart disease treatments, said Testai.

“There should probably be an effort to include brain health outcomes in some of the cardiac literature to make sure we can also measure whether the intervention in the heart leads to an advantage for the brain,” he said.

More research is also needed to determine whether immunomodulation has a beneficial effect on the cognitive trajectory, the statement’s authors noted.

They point out that the interpretation and generalizability of the studies described in the statement are confounded by disparate methodologies, including small sample sizes, cross-sectional designs, and underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic individuals.

‘An Important Step’

Reached for a comment, Natalia S. Rost, MD, Chief of the Stroke Division at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said this paper “is an important step” in terms of pulling together pertinent information on the topic of heart-brain health.

She praised the authors for gathering evidence on risk factors related to atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and coronary heart disease, which is “the part of the puzzle that is controllable.”

This helps reinforce the message that controlling vascular risk factors helps with brain health, said Rost.

But brain health is “much more complex than just vascular health,” she said. It includes other elements such as freedom from epilepsy, migraine, traumatic brain injury, and adult learning disabilities.

No relevant conflicts of interest were disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The statement includes an extensive research review and offers compelling evidence of the inextricable link between heart health and brain health, which investigators said underscores the benefit of early intervention.

The cumulative evidence “confirms that the trajectories of cardiac health and brain health are inextricably intertwined through modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote.

Investigators say the findings reinforce the message that addressing cardiovascular health early in life may deter the onset or progression of cognitive impairment later on.

And the earlier this is done, the better, said lead author Fernando D. Testai, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology and the vascular neurology section head, Department of Neurology and Rehabilitation, University of Illinois, Chicago.

The statement was published online in Stroke.

Bridging the Research Gap

It’s well known that there’s a bidirectional relationship between heart and brain function. For example, heart failure can lead to decreased blood flow that can damage the brain, and stroke in some areas of the brain can affect the heart.

However, that’s only part of the puzzle and doesn’t address all the gaps in the understanding of how cardiovascular disease contributes to cognition, said Testai.

“What we’re trying to do here is to go one step further and describe other connections between the heart and the brain,” he said.

Investigators carried out an extensive PubMed search for heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and coronary heart disease. Researchers detailed the frequency of each condition, mechanisms by which they might cause cognitive impairment, and prospects for prevention and treatment to maintain brain health.

A recurring theme in the paper is the role of inflammation. Evidence shows there are “remarkable similarities in the inflammatory response that takes place,” with both cardiac disease and cognitive decline, said Testai.

Another potential shared mechanism relates to biomarkers, particularly amyloid, which is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

“But some studies show amyloid can also be present in the heart, especially in patients who have decreased ejection fraction,” said Testai.

Robust Heart-Brain Connection

The statement’s authors collected a substantial amount of evidence showing vascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes “can change how the brain processes and clears up amyloid,” Testai added.

The paper also provides a compilation of evidence of shared genetic predispositions when it comes to heart and brain disorders.

“We noticed that some genetic signatures that have historically been associated with heart disease seem to also correlate with structural changes in the brain. That means that at the end of the day, some patients may be born with a genetic predisposition to developing both conditions,” said Testai.

This indicates that the link between the two organs “begins as early as conception” and underscores the importance of adopting healthy lifestyle habits as early as possible, he added.

“That means you can avoid bad habits that eventually lead to hypertension, diabetes, and cholesterol, that eventually will lead to cardiac disease, which eventually will lead to stroke, which eventually will lead to cognitive decline,” Testai noted.

However, cardiovascular health is more complicated than having good genes and adhering to a healthy lifestyle. It’s not clear, for example, why some people who should be predisposed to developing heart disease do not develop it, something Testai refers to as enhanced “resilience.”

For example, Hispanic or Latino patients, who have relatively poor cardiovascular risk factor profiles, seem to be less susceptible to developing cardiac disease.

More Research Needed

While genetics may partly explain the paradox, Testai believes other protective factors are at play, including strong social support networks.

Testai referred to the AHA’s “Life’s Essential 8” — the eight components of cardiovascular health. These include a healthy diet, participation in physical activity, nicotine avoidance, healthy sleep, healthy weight, and healthy levels of blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure.

More evidence is needed to show that effective management of cardiac disease positively affects cognition. Currently, cognitive measures are rarely included in studies examining various heart disease treatments, said Testai.

“There should probably be an effort to include brain health outcomes in some of the cardiac literature to make sure we can also measure whether the intervention in the heart leads to an advantage for the brain,” he said.

More research is also needed to determine whether immunomodulation has a beneficial effect on the cognitive trajectory, the statement’s authors noted.

They point out that the interpretation and generalizability of the studies described in the statement are confounded by disparate methodologies, including small sample sizes, cross-sectional designs, and underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic individuals.

‘An Important Step’

Reached for a comment, Natalia S. Rost, MD, Chief of the Stroke Division at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said this paper “is an important step” in terms of pulling together pertinent information on the topic of heart-brain health.

She praised the authors for gathering evidence on risk factors related to atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and coronary heart disease, which is “the part of the puzzle that is controllable.”

This helps reinforce the message that controlling vascular risk factors helps with brain health, said Rost.

But brain health is “much more complex than just vascular health,” she said. It includes other elements such as freedom from epilepsy, migraine, traumatic brain injury, and adult learning disabilities.

No relevant conflicts of interest were disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The statement includes an extensive research review and offers compelling evidence of the inextricable link between heart health and brain health, which investigators said underscores the benefit of early intervention.

The cumulative evidence “confirms that the trajectories of cardiac health and brain health are inextricably intertwined through modifiable and nonmodifiable factors,” the authors wrote.

Investigators say the findings reinforce the message that addressing cardiovascular health early in life may deter the onset or progression of cognitive impairment later on.

And the earlier this is done, the better, said lead author Fernando D. Testai, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology and the vascular neurology section head, Department of Neurology and Rehabilitation, University of Illinois, Chicago.

The statement was published online in Stroke.

Bridging the Research Gap

It’s well known that there’s a bidirectional relationship between heart and brain function. For example, heart failure can lead to decreased blood flow that can damage the brain, and stroke in some areas of the brain can affect the heart.

However, that’s only part of the puzzle and doesn’t address all the gaps in the understanding of how cardiovascular disease contributes to cognition, said Testai.

“What we’re trying to do here is to go one step further and describe other connections between the heart and the brain,” he said.

Investigators carried out an extensive PubMed search for heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and coronary heart disease. Researchers detailed the frequency of each condition, mechanisms by which they might cause cognitive impairment, and prospects for prevention and treatment to maintain brain health.

A recurring theme in the paper is the role of inflammation. Evidence shows there are “remarkable similarities in the inflammatory response that takes place,” with both cardiac disease and cognitive decline, said Testai.

Another potential shared mechanism relates to biomarkers, particularly amyloid, which is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

“But some studies show amyloid can also be present in the heart, especially in patients who have decreased ejection fraction,” said Testai.

Robust Heart-Brain Connection

The statement’s authors collected a substantial amount of evidence showing vascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes “can change how the brain processes and clears up amyloid,” Testai added.

The paper also provides a compilation of evidence of shared genetic predispositions when it comes to heart and brain disorders.

“We noticed that some genetic signatures that have historically been associated with heart disease seem to also correlate with structural changes in the brain. That means that at the end of the day, some patients may be born with a genetic predisposition to developing both conditions,” said Testai.

This indicates that the link between the two organs “begins as early as conception” and underscores the importance of adopting healthy lifestyle habits as early as possible, he added.

“That means you can avoid bad habits that eventually lead to hypertension, diabetes, and cholesterol, that eventually will lead to cardiac disease, which eventually will lead to stroke, which eventually will lead to cognitive decline,” Testai noted.

However, cardiovascular health is more complicated than having good genes and adhering to a healthy lifestyle. It’s not clear, for example, why some people who should be predisposed to developing heart disease do not develop it, something Testai refers to as enhanced “resilience.”

For example, Hispanic or Latino patients, who have relatively poor cardiovascular risk factor profiles, seem to be less susceptible to developing cardiac disease.

More Research Needed

While genetics may partly explain the paradox, Testai believes other protective factors are at play, including strong social support networks.

Testai referred to the AHA’s “Life’s Essential 8” — the eight components of cardiovascular health. These include a healthy diet, participation in physical activity, nicotine avoidance, healthy sleep, healthy weight, and healthy levels of blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure.

More evidence is needed to show that effective management of cardiac disease positively affects cognition. Currently, cognitive measures are rarely included in studies examining various heart disease treatments, said Testai.

“There should probably be an effort to include brain health outcomes in some of the cardiac literature to make sure we can also measure whether the intervention in the heart leads to an advantage for the brain,” he said.

More research is also needed to determine whether immunomodulation has a beneficial effect on the cognitive trajectory, the statement’s authors noted.

They point out that the interpretation and generalizability of the studies described in the statement are confounded by disparate methodologies, including small sample sizes, cross-sectional designs, and underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic individuals.

‘An Important Step’

Reached for a comment, Natalia S. Rost, MD, Chief of the Stroke Division at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said this paper “is an important step” in terms of pulling together pertinent information on the topic of heart-brain health.

She praised the authors for gathering evidence on risk factors related to atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and coronary heart disease, which is “the part of the puzzle that is controllable.”

This helps reinforce the message that controlling vascular risk factors helps with brain health, said Rost.

But brain health is “much more complex than just vascular health,” she said. It includes other elements such as freedom from epilepsy, migraine, traumatic brain injury, and adult learning disabilities.

No relevant conflicts of interest were disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM STROKE

Ultraprocessed Foods and CVD: Myths vs Facts

I’d like to talk with you about ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) and risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and try to separate some of the facts from the myths. I’d like to discuss a recent report in The Lancet Regional Health that looks at this topic comprehensively and in detail.

This report includes three large-scale prospective cohort studies of US female and male health professionals, more than 200,000 participants in total. It also includes a meta-analysis of 22 international cohorts with about 1.2 million participants. I’d like to acknowledge that I’m a co-author of this study.

What are UPFs, and why are they important? Why do we care, and what are the knowledge gaps? UPFs are generally packaged foods that contain ingredients to extend shelf life and improve taste and palatability. It’s important because 60%-70% of the US diet, if not more, is made up of UPFs. So, the relationship between UPFs and CVD and other health outcomes is actually very important.

And the research to date on this subject has been quite limited.

In other studies, these UPFs have been linked to weight gain and dyslipidemia; some tissue glycation has been found, and some changes in the microbiome. Some studies have linked higher UPF intake with type 2 diabetes. A few have looked at certain selected UPF foods and found a higher risk for CVD, but a really comprehensive look at this question hasn’t been done.

So, that’s what we did in this paper and in the meta-analysis with the 22 cohorts, and we saw a very clear and distinct significant increase in coronary heart disease by 23%, total CVD by 17%, and stroke by 9% when comparing the highest vs the lowest category [of UPF intake]. When we drilled down deeply into the types of UPFs in the US health professional cohorts, we saw that there were some major differences in the relationship with CVD depending on the type of UPF.

In comparing the highest quintile vs the lowest quintile [of total UPF intake], we saw that some of the UPFs were associated with significant elevations in risk for CVD. These included sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats. But some UPFs were linked with a lower risk for CVD. These included breakfast cereals, yogurt, some dairy desserts, and whole grains.

Overall, it seemed that UPFs are actually quite diverse in their association with health. It’s not one size fits all. They’re not all created equal, and some of these differences matter. Although overall we would recommend that our diets be focused on whole foods, primarily plant based, lots of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and other whole foods, it seems from this report and the meta-analysis that certain types of UPFs can be incorporated into a healthy diet and don’t need to be avoided entirely.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She reported receiving donations and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) and risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and try to separate some of the facts from the myths. I’d like to discuss a recent report in The Lancet Regional Health that looks at this topic comprehensively and in detail.

This report includes three large-scale prospective cohort studies of US female and male health professionals, more than 200,000 participants in total. It also includes a meta-analysis of 22 international cohorts with about 1.2 million participants. I’d like to acknowledge that I’m a co-author of this study.

What are UPFs, and why are they important? Why do we care, and what are the knowledge gaps? UPFs are generally packaged foods that contain ingredients to extend shelf life and improve taste and palatability. It’s important because 60%-70% of the US diet, if not more, is made up of UPFs. So, the relationship between UPFs and CVD and other health outcomes is actually very important.

And the research to date on this subject has been quite limited.

In other studies, these UPFs have been linked to weight gain and dyslipidemia; some tissue glycation has been found, and some changes in the microbiome. Some studies have linked higher UPF intake with type 2 diabetes. A few have looked at certain selected UPF foods and found a higher risk for CVD, but a really comprehensive look at this question hasn’t been done.

So, that’s what we did in this paper and in the meta-analysis with the 22 cohorts, and we saw a very clear and distinct significant increase in coronary heart disease by 23%, total CVD by 17%, and stroke by 9% when comparing the highest vs the lowest category [of UPF intake]. When we drilled down deeply into the types of UPFs in the US health professional cohorts, we saw that there were some major differences in the relationship with CVD depending on the type of UPF.

In comparing the highest quintile vs the lowest quintile [of total UPF intake], we saw that some of the UPFs were associated with significant elevations in risk for CVD. These included sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats. But some UPFs were linked with a lower risk for CVD. These included breakfast cereals, yogurt, some dairy desserts, and whole grains.

Overall, it seemed that UPFs are actually quite diverse in their association with health. It’s not one size fits all. They’re not all created equal, and some of these differences matter. Although overall we would recommend that our diets be focused on whole foods, primarily plant based, lots of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and other whole foods, it seems from this report and the meta-analysis that certain types of UPFs can be incorporated into a healthy diet and don’t need to be avoided entirely.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She reported receiving donations and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about ultraprocessed foods (UPFs) and risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and try to separate some of the facts from the myths. I’d like to discuss a recent report in The Lancet Regional Health that looks at this topic comprehensively and in detail.

This report includes three large-scale prospective cohort studies of US female and male health professionals, more than 200,000 participants in total. It also includes a meta-analysis of 22 international cohorts with about 1.2 million participants. I’d like to acknowledge that I’m a co-author of this study.

What are UPFs, and why are they important? Why do we care, and what are the knowledge gaps? UPFs are generally packaged foods that contain ingredients to extend shelf life and improve taste and palatability. It’s important because 60%-70% of the US diet, if not more, is made up of UPFs. So, the relationship between UPFs and CVD and other health outcomes is actually very important.

And the research to date on this subject has been quite limited.

In other studies, these UPFs have been linked to weight gain and dyslipidemia; some tissue glycation has been found, and some changes in the microbiome. Some studies have linked higher UPF intake with type 2 diabetes. A few have looked at certain selected UPF foods and found a higher risk for CVD, but a really comprehensive look at this question hasn’t been done.

So, that’s what we did in this paper and in the meta-analysis with the 22 cohorts, and we saw a very clear and distinct significant increase in coronary heart disease by 23%, total CVD by 17%, and stroke by 9% when comparing the highest vs the lowest category [of UPF intake]. When we drilled down deeply into the types of UPFs in the US health professional cohorts, we saw that there were some major differences in the relationship with CVD depending on the type of UPF.

In comparing the highest quintile vs the lowest quintile [of total UPF intake], we saw that some of the UPFs were associated with significant elevations in risk for CVD. These included sugar-sweetened beverages and processed meats. But some UPFs were linked with a lower risk for CVD. These included breakfast cereals, yogurt, some dairy desserts, and whole grains.

Overall, it seemed that UPFs are actually quite diverse in their association with health. It’s not one size fits all. They’re not all created equal, and some of these differences matter. Although overall we would recommend that our diets be focused on whole foods, primarily plant based, lots of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and other whole foods, it seems from this report and the meta-analysis that certain types of UPFs can be incorporated into a healthy diet and don’t need to be avoided entirely.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. She reported receiving donations and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Heard of ApoB Testing? New Guidelines

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

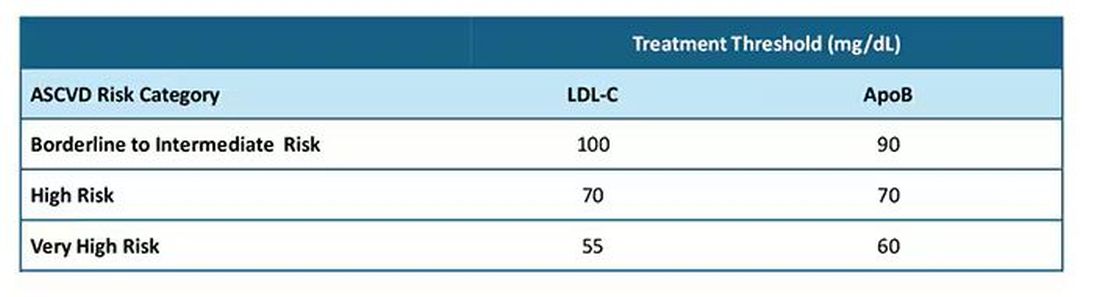

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Heart Attack, Stroke Survivors at High Risk for Long COVID

Primary care doctors and specialists should advise patients who have already experienced a heart attack or stroke that they are at a higher risk for long COVID and need to take steps to avoid contracting the virus, according to new research.

The study, led by researchers at Columbia University, New York City, suggests that anyone with cardiovascular disease (CVD) — defined as having experienced a heart attack or stroke — should consider getting the updated COVID vaccine boosters. They also suggest patients with CVD take other steps to avoid an acute infection, such as avoiding crowded indoor spaces.

There is no specific test or treatment for long COVID, which can become disabling and chronic. Long COVID is defined by the failure to recover from acute COVID-19 in 90 days.

The scientists used data from nearly 5000 people enrolled in 14 established, ongoing research programs, including the 76-year-old Framingham Heart Study. The results of the analysis of the “mega-cohort” were published in JAMA Network Open.

Most of the 14 studies already had 10-20 years of data on the cardiac health of thousands of enrollees, said Norrina B. Allen, one of the authors and a cardiac epidemiologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

“This is a particularly strong study that looked at risk factors — or individual health — prior to developing COVID and their impact on the likely of recovering from COVID,” she said.

In addition to those with CVD, women and adults with preexisting chronic illnesses took longer to recover.

More than 20% of those in the large, racially and ethnically diverse US population–based study did not recover from COVID in 90 days. The researchers found that the median self-reported time to recovery from acute infection was 20 days.

While women and those with chronic illness had a higher risk for long COVID, vaccination and infection with the Omicron variant wave were associated with shorter recovery times.

These findings make sense, said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System and clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We also see that COVID-19 can lead to new-onset cardiovascular disease,” said Al-Aly, who was not involved in the study. “There is clearly a (link) between COVID and cardiovascular disease. These two seem to be intimately intertwined. In my view, this emphasizes the importance of targeting these individuals for vaccination and potentially antivirals (when they get infected) to help reduce their risk of adverse events and ameliorate their chance of full and fast recovery.”

The study used data from the Collaborative Cohort of Cohorts for COVID-19 Research. The long list of researchers contributing to this study includes epidemiologists, biostatisticians, neurologists, pulmonologists, and cardiologists. The data come from a list of cohorts like the Framingham Heart Study, which identified key risk factors for CVD, including cholesterol levels. Other studies include the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, which began in the mid-1980s. Researchers there recruited a cohort of 15,792 men and women in rural North Carolina and Mississippi and suburban Minneapolis. They enrolled a high number of African American participants, who have been underrepresented in past studies. Other cohorts focused on young adults with CVD and Hispanics, while another focused on people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Lead author Elizabeth C. Oelsner, MD, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, said she was not surprised by the CVD-long COVID link.

“We were aware that individuals with CVD were at higher risk of a more severe acute infection,” she said. “We were also seeing evidence that long and severe infection led to persistent symptoms.”

Oelsner noted that many patients still take more than 3 months to recover, even during the Omicron wave.

“While that has improved over the course of the pandemic, many individuals are taking a very long time to recover, and that can have a huge burden on the patient,” she said.

She encourages healthcare providers to tell patients at higher risk to take steps to avoid the virus, including vaccination and boosters.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care doctors and specialists should advise patients who have already experienced a heart attack or stroke that they are at a higher risk for long COVID and need to take steps to avoid contracting the virus, according to new research.

The study, led by researchers at Columbia University, New York City, suggests that anyone with cardiovascular disease (CVD) — defined as having experienced a heart attack or stroke — should consider getting the updated COVID vaccine boosters. They also suggest patients with CVD take other steps to avoid an acute infection, such as avoiding crowded indoor spaces.

There is no specific test or treatment for long COVID, which can become disabling and chronic. Long COVID is defined by the failure to recover from acute COVID-19 in 90 days.

The scientists used data from nearly 5000 people enrolled in 14 established, ongoing research programs, including the 76-year-old Framingham Heart Study. The results of the analysis of the “mega-cohort” were published in JAMA Network Open.

Most of the 14 studies already had 10-20 years of data on the cardiac health of thousands of enrollees, said Norrina B. Allen, one of the authors and a cardiac epidemiologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

“This is a particularly strong study that looked at risk factors — or individual health — prior to developing COVID and their impact on the likely of recovering from COVID,” she said.

In addition to those with CVD, women and adults with preexisting chronic illnesses took longer to recover.

More than 20% of those in the large, racially and ethnically diverse US population–based study did not recover from COVID in 90 days. The researchers found that the median self-reported time to recovery from acute infection was 20 days.

While women and those with chronic illness had a higher risk for long COVID, vaccination and infection with the Omicron variant wave were associated with shorter recovery times.

These findings make sense, said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System and clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We also see that COVID-19 can lead to new-onset cardiovascular disease,” said Al-Aly, who was not involved in the study. “There is clearly a (link) between COVID and cardiovascular disease. These two seem to be intimately intertwined. In my view, this emphasizes the importance of targeting these individuals for vaccination and potentially antivirals (when they get infected) to help reduce their risk of adverse events and ameliorate their chance of full and fast recovery.”

The study used data from the Collaborative Cohort of Cohorts for COVID-19 Research. The long list of researchers contributing to this study includes epidemiologists, biostatisticians, neurologists, pulmonologists, and cardiologists. The data come from a list of cohorts like the Framingham Heart Study, which identified key risk factors for CVD, including cholesterol levels. Other studies include the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, which began in the mid-1980s. Researchers there recruited a cohort of 15,792 men and women in rural North Carolina and Mississippi and suburban Minneapolis. They enrolled a high number of African American participants, who have been underrepresented in past studies. Other cohorts focused on young adults with CVD and Hispanics, while another focused on people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Lead author Elizabeth C. Oelsner, MD, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, said she was not surprised by the CVD-long COVID link.

“We were aware that individuals with CVD were at higher risk of a more severe acute infection,” she said. “We were also seeing evidence that long and severe infection led to persistent symptoms.”

Oelsner noted that many patients still take more than 3 months to recover, even during the Omicron wave.

“While that has improved over the course of the pandemic, many individuals are taking a very long time to recover, and that can have a huge burden on the patient,” she said.

She encourages healthcare providers to tell patients at higher risk to take steps to avoid the virus, including vaccination and boosters.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care doctors and specialists should advise patients who have already experienced a heart attack or stroke that they are at a higher risk for long COVID and need to take steps to avoid contracting the virus, according to new research.

The study, led by researchers at Columbia University, New York City, suggests that anyone with cardiovascular disease (CVD) — defined as having experienced a heart attack or stroke — should consider getting the updated COVID vaccine boosters. They also suggest patients with CVD take other steps to avoid an acute infection, such as avoiding crowded indoor spaces.

There is no specific test or treatment for long COVID, which can become disabling and chronic. Long COVID is defined by the failure to recover from acute COVID-19 in 90 days.

The scientists used data from nearly 5000 people enrolled in 14 established, ongoing research programs, including the 76-year-old Framingham Heart Study. The results of the analysis of the “mega-cohort” were published in JAMA Network Open.

Most of the 14 studies already had 10-20 years of data on the cardiac health of thousands of enrollees, said Norrina B. Allen, one of the authors and a cardiac epidemiologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

“This is a particularly strong study that looked at risk factors — or individual health — prior to developing COVID and their impact on the likely of recovering from COVID,” she said.

In addition to those with CVD, women and adults with preexisting chronic illnesses took longer to recover.

More than 20% of those in the large, racially and ethnically diverse US population–based study did not recover from COVID in 90 days. The researchers found that the median self-reported time to recovery from acute infection was 20 days.

While women and those with chronic illness had a higher risk for long COVID, vaccination and infection with the Omicron variant wave were associated with shorter recovery times.

These findings make sense, said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, chief of research at Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System and clinical epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

“We also see that COVID-19 can lead to new-onset cardiovascular disease,” said Al-Aly, who was not involved in the study. “There is clearly a (link) between COVID and cardiovascular disease. These two seem to be intimately intertwined. In my view, this emphasizes the importance of targeting these individuals for vaccination and potentially antivirals (when they get infected) to help reduce their risk of adverse events and ameliorate their chance of full and fast recovery.”

The study used data from the Collaborative Cohort of Cohorts for COVID-19 Research. The long list of researchers contributing to this study includes epidemiologists, biostatisticians, neurologists, pulmonologists, and cardiologists. The data come from a list of cohorts like the Framingham Heart Study, which identified key risk factors for CVD, including cholesterol levels. Other studies include the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, which began in the mid-1980s. Researchers there recruited a cohort of 15,792 men and women in rural North Carolina and Mississippi and suburban Minneapolis. They enrolled a high number of African American participants, who have been underrepresented in past studies. Other cohorts focused on young adults with CVD and Hispanics, while another focused on people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Lead author Elizabeth C. Oelsner, MD, of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, said she was not surprised by the CVD-long COVID link.

“We were aware that individuals with CVD were at higher risk of a more severe acute infection,” she said. “We were also seeing evidence that long and severe infection led to persistent symptoms.”

Oelsner noted that many patients still take more than 3 months to recover, even during the Omicron wave.

“While that has improved over the course of the pandemic, many individuals are taking a very long time to recover, and that can have a huge burden on the patient,” she said.

She encourages healthcare providers to tell patients at higher risk to take steps to avoid the virus, including vaccination and boosters.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic Risk for Gout Raises Risk for Cardiovascular Disease Independent of Urate Level

TOPLINE:

Genetic predisposition to gout, unfavorable lifestyle habits, and poor metabolic health are associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD); however, adherence to a healthy lifestyle can reduce this risk by up to 62%, even in individuals with high genetic risk.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers investigated the association between genetic predisposition to gout, combined with lifestyle habits, and the risk for CVD in two diverse prospective cohorts from different ancestral backgrounds.

- They analyzed the data of 224,689 participants of European descent from the UK Biobank (mean age, 57.0 years; 56.1% women) and 50,364 participants of East Asian descent from the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES; mean age, 53.7 years; 66.0% women).

- The genetic predisposition to gout was evaluated using a polygenic risk score (PRS) derived from a metagenome-wide association study, and the participants were categorized into low, intermediate, and high genetic risk groups based on their PRS for gout.

- A favorable lifestyle was defined as having ≥ 3 healthy lifestyle factors, and 0-1 metabolic syndrome factor defined the ideal metabolic health status.

- The incident CVD risk was evaluated according to genetic risk, lifestyle habits, and metabolic syndrome.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals in the high genetic risk group had a higher risk for CVD than those in the low genetic risk group in both the UK Biobank (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; P < .001) and KoGES (aHR, 1.31; P = .024) cohorts.

- In the UK Biobank cohort, individuals with a high genetic risk for gout and unfavorable lifestyle choices had a 1.99 times higher risk for incident CVD than those with low genetic risk (aHR, 1.99; P < .001); similar outcomes were observed in the KoGES cohort.

- Similarly, individuals with a high genetic risk for gout and poor metabolic health in the UK Biobank cohort had a 2.16 times higher risk for CVD than those with low genetic risk (aHR, 2.16; P < .001 for both); outcomes were no different in the KoGES cohort.

- Improving metabolic health and adhering to a healthy lifestyle reduced the risk for CVD by 62% in individuals with high genetic risk and by 46% in those with low genetic risk (P < .001 for both).

IN PRACTICE:

“PRS for gout can be used for preventing not only gout but also CVD. It is possible to identify individuals with high genetic risk for gout and strongly recommend modifying lifestyle habits. Weight reduction, smoking cessation, regular exercise, and eating healthy food are effective strategies to prevent gout and CVD,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Ki Won Moon, MD, PhD, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Republic of Korea, and SangHyuk Jung, PhD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and was published online on October 8, 2024, in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The definitions of lifestyle and metabolic syndrome were different in each cohort, which may have affected the findings. Data on lifestyle behaviors and metabolic health statuses were collected at enrollment, but these variables may have changed during the follow-up period, which potentially introduced bias into the results. This study was not able to establish causality between genetic predisposition to gout and the incident risk for CVD.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Genetic predisposition to gout, unfavorable lifestyle habits, and poor metabolic health are associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD); however, adherence to a healthy lifestyle can reduce this risk by up to 62%, even in individuals with high genetic risk.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers investigated the association between genetic predisposition to gout, combined with lifestyle habits, and the risk for CVD in two diverse prospective cohorts from different ancestral backgrounds.

- They analyzed the data of 224,689 participants of European descent from the UK Biobank (mean age, 57.0 years; 56.1% women) and 50,364 participants of East Asian descent from the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES; mean age, 53.7 years; 66.0% women).

- The genetic predisposition to gout was evaluated using a polygenic risk score (PRS) derived from a metagenome-wide association study, and the participants were categorized into low, intermediate, and high genetic risk groups based on their PRS for gout.

- A favorable lifestyle was defined as having ≥ 3 healthy lifestyle factors, and 0-1 metabolic syndrome factor defined the ideal metabolic health status.

- The incident CVD risk was evaluated according to genetic risk, lifestyle habits, and metabolic syndrome.

TAKEAWAY:

- Individuals in the high genetic risk group had a higher risk for CVD than those in the low genetic risk group in both the UK Biobank (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; P < .001) and KoGES (aHR, 1.31; P = .024) cohorts.