User login

Monkeypox: What’s a pediatrician to do?

Not long ago, a pediatrician working in a local urgent care clinic called me about a teenage girl with a pruritic rash. She described vesicles and pustules located primarily on the face and arms with no surrounding cellulitis or other exam findings.

“She probably has impetigo,” my colleague said. “But I took a travel and exposure history and learned that her grandma had recently returned home from visiting family in the Congo. Do you think I need to worry about monkeypox?”

While most pediatricians in the United States have never seen a case of monkeypox, the virus is not new. An orthopox, it belongs to the same genus that includes smallpox and cowpox viruses. It was discovered in 1958 when two colonies of monkeys kept for research developed pox-like rashes. The earliest human case was reported in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and now the virus is endemic in some counties in Central and West Africa.

Monkeypox virus is a zoonotic disease – it can spread from animals to people. Rodents and other small mammals – not monkeys – are thought to be the most likely reservoir. The virus typically spreads from person to person through close contact with skin or respiratory secretions or contact with contaminated fomites. Typical infection begins with fever, lymphadenopathy, and flulike symptoms that include headache and malaise. One to four days after the onset of fever, the characteristic rash begins as macular lesions that evolve into papules, then vesicles, and finally pustules. Pustular lesions are deep-seated, well circumscribed, and are usually the same size and in the same stage of development on a given body site. The rash often starts on the face or the mouth, and then moves to the extremities, including the palms and soles. Over time, the lesions umbilicate and ultimately crust over.

On May 20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a Health Advisory describing a case of monkeypox in a patient in Massachusetts. A single case normally wouldn’t cause too much alarm. In fact, there were two cases reported in the United States in 2021, both in travelers returning to the United States from Nigeria, a country in which the virus is endemic. No transmissions from these individuals to close contacts were identified.

The Massachusetts case was remarkable for two reasons. It occurred in an individual who had recently returned from a trip to Canada, which is not a country in which the virus is endemic. Additionally, it occurred in the context of a global outbreak of monkey pox that has, to date, disproportionately affected individuals who identify as men who have sex with men. Patients have often lacked the characteristic prodrome and many have had rash localized to the perianal and genital area, with or without symptoms of proctitis (anorectal pain, tenesmus, and bleeding). Clinically, some lesions mimicked sexually transmitted infections that the occur in the anogenital area, including herpes, syphilis, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

As of May 31, 2022, 17 persons in nine states had been diagnosed with presumed monkeypox virus infection. They ranged in age from 28 to 61 years and 16/17 identified as MSM. Fourteen reported international travel in the 3 weeks before developing symptoms. As of June 12, that number had grown to 53, while worldwide the number of confirmed and suspected cases reached 1,584. Up-to-date case counts are available at https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox.

Back on the phone, my colleague laughed a little nervously. “I guess I’m not really worried about monkeypox in my patient.” She paused and then asked, “This isn’t going to be the next pandemic, is it?”

Public health experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have been reassuring in that regard. Two vaccines are available for the prevention of monkeypox. JYNNEOS is a nonreplicating live viral vaccine licensed as a two-dose series to prevent both monkeypox and smallpox. ACAM 2000 is a live Vaccinia virus preparation licensed to prevent smallpox. These vaccines are effective when given before exposure but are thought to also beneficial when given as postexposure prophylaxis. According to the CDC, vaccination within 4 days of exposure can prevent the development of disease. Vaccination within 14 days of exposure may not prevent the development of disease but may lessen symptoms. Treatment is generally supportive but antiviral therapy could be considered for individuals with severe disease. Tecovirmat is Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of smallpox but is available under nonresearch Expanded Access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol for the treatment of children and adults with severe orthopox infections, including monkeypox.

So, what’s a pediatrician to do? Take a good travel history, as my colleague did, because that is good medicine. At this point in an outbreak though, a lack of travel does not exclude the diagnosis. Perform a thorough exam of skin and mucosal areas. When there are rashes in the genital or perianal area, consider the possibility of monkeypox in addition to typical sexually transmitted infections. Ask about exposure to other persons with similar rashes, as well as close or intimate contact with a persons in a social network experiencing monkeypox infections. This includes MSM who meet partners through an online website, app, or at social events. Monkeypox can also be spread through contact with an animal (dead or alive) that is an African endemic species or use of a product derived from such animals. Public health experts encourage clinicians to be alert for rash illnesses consistent with monkeypox, regardless of a patient’s gender or sexual orientation, history of international travel, or specific risk factors.

Pediatricians see many kids with rashes, and while cases of monkeypox climb daily, the disease is still very rare. Given the media coverage of the outbreak, pediatricians should be prepared for questions from patients and their parents. Clinicians who suspect a case of monkeypox should contact their local or state health department for guidance and the need for testing. Tips for recognizing monkeypox and distinguishing it from more common viral illnesses such as chicken pox are available at www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Not long ago, a pediatrician working in a local urgent care clinic called me about a teenage girl with a pruritic rash. She described vesicles and pustules located primarily on the face and arms with no surrounding cellulitis or other exam findings.

“She probably has impetigo,” my colleague said. “But I took a travel and exposure history and learned that her grandma had recently returned home from visiting family in the Congo. Do you think I need to worry about monkeypox?”

While most pediatricians in the United States have never seen a case of monkeypox, the virus is not new. An orthopox, it belongs to the same genus that includes smallpox and cowpox viruses. It was discovered in 1958 when two colonies of monkeys kept for research developed pox-like rashes. The earliest human case was reported in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and now the virus is endemic in some counties in Central and West Africa.

Monkeypox virus is a zoonotic disease – it can spread from animals to people. Rodents and other small mammals – not monkeys – are thought to be the most likely reservoir. The virus typically spreads from person to person through close contact with skin or respiratory secretions or contact with contaminated fomites. Typical infection begins with fever, lymphadenopathy, and flulike symptoms that include headache and malaise. One to four days after the onset of fever, the characteristic rash begins as macular lesions that evolve into papules, then vesicles, and finally pustules. Pustular lesions are deep-seated, well circumscribed, and are usually the same size and in the same stage of development on a given body site. The rash often starts on the face or the mouth, and then moves to the extremities, including the palms and soles. Over time, the lesions umbilicate and ultimately crust over.

On May 20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a Health Advisory describing a case of monkeypox in a patient in Massachusetts. A single case normally wouldn’t cause too much alarm. In fact, there were two cases reported in the United States in 2021, both in travelers returning to the United States from Nigeria, a country in which the virus is endemic. No transmissions from these individuals to close contacts were identified.

The Massachusetts case was remarkable for two reasons. It occurred in an individual who had recently returned from a trip to Canada, which is not a country in which the virus is endemic. Additionally, it occurred in the context of a global outbreak of monkey pox that has, to date, disproportionately affected individuals who identify as men who have sex with men. Patients have often lacked the characteristic prodrome and many have had rash localized to the perianal and genital area, with or without symptoms of proctitis (anorectal pain, tenesmus, and bleeding). Clinically, some lesions mimicked sexually transmitted infections that the occur in the anogenital area, including herpes, syphilis, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

As of May 31, 2022, 17 persons in nine states had been diagnosed with presumed monkeypox virus infection. They ranged in age from 28 to 61 years and 16/17 identified as MSM. Fourteen reported international travel in the 3 weeks before developing symptoms. As of June 12, that number had grown to 53, while worldwide the number of confirmed and suspected cases reached 1,584. Up-to-date case counts are available at https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox.

Back on the phone, my colleague laughed a little nervously. “I guess I’m not really worried about monkeypox in my patient.” She paused and then asked, “This isn’t going to be the next pandemic, is it?”

Public health experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have been reassuring in that regard. Two vaccines are available for the prevention of monkeypox. JYNNEOS is a nonreplicating live viral vaccine licensed as a two-dose series to prevent both monkeypox and smallpox. ACAM 2000 is a live Vaccinia virus preparation licensed to prevent smallpox. These vaccines are effective when given before exposure but are thought to also beneficial when given as postexposure prophylaxis. According to the CDC, vaccination within 4 days of exposure can prevent the development of disease. Vaccination within 14 days of exposure may not prevent the development of disease but may lessen symptoms. Treatment is generally supportive but antiviral therapy could be considered for individuals with severe disease. Tecovirmat is Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of smallpox but is available under nonresearch Expanded Access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol for the treatment of children and adults with severe orthopox infections, including monkeypox.

So, what’s a pediatrician to do? Take a good travel history, as my colleague did, because that is good medicine. At this point in an outbreak though, a lack of travel does not exclude the diagnosis. Perform a thorough exam of skin and mucosal areas. When there are rashes in the genital or perianal area, consider the possibility of monkeypox in addition to typical sexually transmitted infections. Ask about exposure to other persons with similar rashes, as well as close or intimate contact with a persons in a social network experiencing monkeypox infections. This includes MSM who meet partners through an online website, app, or at social events. Monkeypox can also be spread through contact with an animal (dead or alive) that is an African endemic species or use of a product derived from such animals. Public health experts encourage clinicians to be alert for rash illnesses consistent with monkeypox, regardless of a patient’s gender or sexual orientation, history of international travel, or specific risk factors.

Pediatricians see many kids with rashes, and while cases of monkeypox climb daily, the disease is still very rare. Given the media coverage of the outbreak, pediatricians should be prepared for questions from patients and their parents. Clinicians who suspect a case of monkeypox should contact their local or state health department for guidance and the need for testing. Tips for recognizing monkeypox and distinguishing it from more common viral illnesses such as chicken pox are available at www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Not long ago, a pediatrician working in a local urgent care clinic called me about a teenage girl with a pruritic rash. She described vesicles and pustules located primarily on the face and arms with no surrounding cellulitis or other exam findings.

“She probably has impetigo,” my colleague said. “But I took a travel and exposure history and learned that her grandma had recently returned home from visiting family in the Congo. Do you think I need to worry about monkeypox?”

While most pediatricians in the United States have never seen a case of monkeypox, the virus is not new. An orthopox, it belongs to the same genus that includes smallpox and cowpox viruses. It was discovered in 1958 when two colonies of monkeys kept for research developed pox-like rashes. The earliest human case was reported in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and now the virus is endemic in some counties in Central and West Africa.

Monkeypox virus is a zoonotic disease – it can spread from animals to people. Rodents and other small mammals – not monkeys – are thought to be the most likely reservoir. The virus typically spreads from person to person through close contact with skin or respiratory secretions or contact with contaminated fomites. Typical infection begins with fever, lymphadenopathy, and flulike symptoms that include headache and malaise. One to four days after the onset of fever, the characteristic rash begins as macular lesions that evolve into papules, then vesicles, and finally pustules. Pustular lesions are deep-seated, well circumscribed, and are usually the same size and in the same stage of development on a given body site. The rash often starts on the face or the mouth, and then moves to the extremities, including the palms and soles. Over time, the lesions umbilicate and ultimately crust over.

On May 20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a Health Advisory describing a case of monkeypox in a patient in Massachusetts. A single case normally wouldn’t cause too much alarm. In fact, there were two cases reported in the United States in 2021, both in travelers returning to the United States from Nigeria, a country in which the virus is endemic. No transmissions from these individuals to close contacts were identified.

The Massachusetts case was remarkable for two reasons. It occurred in an individual who had recently returned from a trip to Canada, which is not a country in which the virus is endemic. Additionally, it occurred in the context of a global outbreak of monkey pox that has, to date, disproportionately affected individuals who identify as men who have sex with men. Patients have often lacked the characteristic prodrome and many have had rash localized to the perianal and genital area, with or without symptoms of proctitis (anorectal pain, tenesmus, and bleeding). Clinically, some lesions mimicked sexually transmitted infections that the occur in the anogenital area, including herpes, syphilis, and lymphogranuloma venereum.

As of May 31, 2022, 17 persons in nine states had been diagnosed with presumed monkeypox virus infection. They ranged in age from 28 to 61 years and 16/17 identified as MSM. Fourteen reported international travel in the 3 weeks before developing symptoms. As of June 12, that number had grown to 53, while worldwide the number of confirmed and suspected cases reached 1,584. Up-to-date case counts are available at https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox.

Back on the phone, my colleague laughed a little nervously. “I guess I’m not really worried about monkeypox in my patient.” She paused and then asked, “This isn’t going to be the next pandemic, is it?”

Public health experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have been reassuring in that regard. Two vaccines are available for the prevention of monkeypox. JYNNEOS is a nonreplicating live viral vaccine licensed as a two-dose series to prevent both monkeypox and smallpox. ACAM 2000 is a live Vaccinia virus preparation licensed to prevent smallpox. These vaccines are effective when given before exposure but are thought to also beneficial when given as postexposure prophylaxis. According to the CDC, vaccination within 4 days of exposure can prevent the development of disease. Vaccination within 14 days of exposure may not prevent the development of disease but may lessen symptoms. Treatment is generally supportive but antiviral therapy could be considered for individuals with severe disease. Tecovirmat is Food and Drug Administration approved for the treatment of smallpox but is available under nonresearch Expanded Access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol for the treatment of children and adults with severe orthopox infections, including monkeypox.

So, what’s a pediatrician to do? Take a good travel history, as my colleague did, because that is good medicine. At this point in an outbreak though, a lack of travel does not exclude the diagnosis. Perform a thorough exam of skin and mucosal areas. When there are rashes in the genital or perianal area, consider the possibility of monkeypox in addition to typical sexually transmitted infections. Ask about exposure to other persons with similar rashes, as well as close or intimate contact with a persons in a social network experiencing monkeypox infections. This includes MSM who meet partners through an online website, app, or at social events. Monkeypox can also be spread through contact with an animal (dead or alive) that is an African endemic species or use of a product derived from such animals. Public health experts encourage clinicians to be alert for rash illnesses consistent with monkeypox, regardless of a patient’s gender or sexual orientation, history of international travel, or specific risk factors.

Pediatricians see many kids with rashes, and while cases of monkeypox climb daily, the disease is still very rare. Given the media coverage of the outbreak, pediatricians should be prepared for questions from patients and their parents. Clinicians who suspect a case of monkeypox should contact their local or state health department for guidance and the need for testing. Tips for recognizing monkeypox and distinguishing it from more common viral illnesses such as chicken pox are available at www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/clinicians/clinical-recognition.html.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Pediatric hepatitis has not increased during pandemic: CDC

The number of pediatric hepatitis cases has remained steady since 2017, new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests, despite the recent investigation into children with hepatitis of unknown cause. The study also found that there was no indication of elevated rates of adenovirus type 40/41 infection in children.

But Rohit Kohli, MBBS, MS, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California, says that although the study is “well-designed and robust,” that does not mean that these hepatitis cases of unknown origin are no longer a concern. He was not involved with the CDC research. “As a clinician, I’m still worried,” he said. “Why I feel like this is not conclusive is that there are other data from entities like the United Kingdom Health Security Agency that are incongruent with [these findings],” he said.

The research was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In November 2021, the Alabama Department of Public Health began an investigation with the CDC after a cluster of children were admitted to a children’s hospital in the state with severe hepatitis, who all tested positive for adenovirus. When the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency announced an investigation into similar cases in early April 2022, the CDC decided to expand their search nationally.

Now, as of June 15, the agency is investigating 290 cases in 41 states and U.S. territories. Worldwide, 650 cases in 33 countries have been reported, according to the most recent update by the World Health Organization on May 27, 2022. At least 38 patients have needed liver transplants, and nine deaths have been reported to WHO.

In its most recent press call on the topic, the CDC announced that it’s aware of six deaths in the United States through May 20, 2022. The COVID-19 vaccine has been ruled out as a potential cause because the majority of affected children are unvaccinated or are too young to receive the vaccine. Adenovirus infection remains a leading suspect in these sick children because the virus has been detected in 60.8% of tested cases, WHO reports.

Investigators have detected an increase in reported pediatric hepatitis cases, compared with prior years in the United Kingdom, but it was not clear whether that same pattern would be found in the United States. Neither pediatric hepatitis nor adenovirus type 40/41 are reportable conditions in the United States. In the May 20 CDC press call, Umesh Parashar, MD, chief of the CDC’s Viral Gastroenteritis Branch, said that an estimated 1,500-2,000 children aged younger than 10 are hospitalized in the United States for hepatitis every year. “That’s a fairly large number,” he said, and it might make it difficult to detect a small increase in cases.

To better estimate trends in pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus infection in the United States, investigators collected available data on emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants associated with hepatitis in children as well as adenovirus stool testing results. Researchers used four large databases: the National Syndromic Surveillance Program; the Premier Healthcare Database Special Release; the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network; and Labcorp, which is a large commercial lab network.

To account for changes in health care utilization in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the team compared hepatitis-associated ED visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants from October 2021 to March 2022 versus the same months (January to March and October to December) in 2017, 2018, and 2019. For adenovirus stool testing, results from October 2021 to March 2022 were compared with the same calendar months (October to March) from 2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2019-2020, to help control for seasonality.

Investigators found no statistically significant increases in the outcomes during October 2021 to March 2022 versus pre-pandemic years:

- Weekly ED visits with hepatitis-associated discharge codes

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalizations in children aged 0-4 years (22 vs. 19.5; P = .26)

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalization in children aged 5-11 years (12 vs. 10.5; P = .42)

- Monthly liver transplants (5 vs. 4; P = .19)

- Percentage of stool specimens positive for adenovirus types 40/41, though the number of specimens tested was highest in March 2022

The authors acknowledged that pediatric hepatitis is rare, so it may be difficult tease out small changes in the number of cases. Also, data on hospitalizations and liver transplants have a 2- to 3-month reporting delay, so the case counts for March 2022 “might be underreported,” they wrote. Mr. Kohli noted that because hepatitis and adenovirus are not reportable conditions, the analysis relied on retrospective data from insurance companies and electronic medical records. Retrospective data are inherently limited, compared with prospective analyses, he said, and it’s possible that certain cases could be included in more than one database and thus be double-counted, whereas other cases could be missed entirely.

These findings also conflict with data from the United Kingdom, which in May reported that the average number of hepatitis cases had increased, compared with previous years, he said. More data are needed, he said, and he is involved with a study with the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that is also collecting data to try to understand whether there has been an uptick in pediatric hepatitis cases. The study will collect patient data directly from hospitals as well as include additional pathology data, such as biopsy results.

“We should not be inhibited to look further academically – and public health–wise – while we take into cognizance this very good, robust attempt from the CDC,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of pediatric hepatitis cases has remained steady since 2017, new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests, despite the recent investigation into children with hepatitis of unknown cause. The study also found that there was no indication of elevated rates of adenovirus type 40/41 infection in children.

But Rohit Kohli, MBBS, MS, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California, says that although the study is “well-designed and robust,” that does not mean that these hepatitis cases of unknown origin are no longer a concern. He was not involved with the CDC research. “As a clinician, I’m still worried,” he said. “Why I feel like this is not conclusive is that there are other data from entities like the United Kingdom Health Security Agency that are incongruent with [these findings],” he said.

The research was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In November 2021, the Alabama Department of Public Health began an investigation with the CDC after a cluster of children were admitted to a children’s hospital in the state with severe hepatitis, who all tested positive for adenovirus. When the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency announced an investigation into similar cases in early April 2022, the CDC decided to expand their search nationally.

Now, as of June 15, the agency is investigating 290 cases in 41 states and U.S. territories. Worldwide, 650 cases in 33 countries have been reported, according to the most recent update by the World Health Organization on May 27, 2022. At least 38 patients have needed liver transplants, and nine deaths have been reported to WHO.

In its most recent press call on the topic, the CDC announced that it’s aware of six deaths in the United States through May 20, 2022. The COVID-19 vaccine has been ruled out as a potential cause because the majority of affected children are unvaccinated or are too young to receive the vaccine. Adenovirus infection remains a leading suspect in these sick children because the virus has been detected in 60.8% of tested cases, WHO reports.

Investigators have detected an increase in reported pediatric hepatitis cases, compared with prior years in the United Kingdom, but it was not clear whether that same pattern would be found in the United States. Neither pediatric hepatitis nor adenovirus type 40/41 are reportable conditions in the United States. In the May 20 CDC press call, Umesh Parashar, MD, chief of the CDC’s Viral Gastroenteritis Branch, said that an estimated 1,500-2,000 children aged younger than 10 are hospitalized in the United States for hepatitis every year. “That’s a fairly large number,” he said, and it might make it difficult to detect a small increase in cases.

To better estimate trends in pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus infection in the United States, investigators collected available data on emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants associated with hepatitis in children as well as adenovirus stool testing results. Researchers used four large databases: the National Syndromic Surveillance Program; the Premier Healthcare Database Special Release; the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network; and Labcorp, which is a large commercial lab network.

To account for changes in health care utilization in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the team compared hepatitis-associated ED visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants from October 2021 to March 2022 versus the same months (January to March and October to December) in 2017, 2018, and 2019. For adenovirus stool testing, results from October 2021 to March 2022 were compared with the same calendar months (October to March) from 2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2019-2020, to help control for seasonality.

Investigators found no statistically significant increases in the outcomes during October 2021 to March 2022 versus pre-pandemic years:

- Weekly ED visits with hepatitis-associated discharge codes

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalizations in children aged 0-4 years (22 vs. 19.5; P = .26)

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalization in children aged 5-11 years (12 vs. 10.5; P = .42)

- Monthly liver transplants (5 vs. 4; P = .19)

- Percentage of stool specimens positive for adenovirus types 40/41, though the number of specimens tested was highest in March 2022

The authors acknowledged that pediatric hepatitis is rare, so it may be difficult tease out small changes in the number of cases. Also, data on hospitalizations and liver transplants have a 2- to 3-month reporting delay, so the case counts for March 2022 “might be underreported,” they wrote. Mr. Kohli noted that because hepatitis and adenovirus are not reportable conditions, the analysis relied on retrospective data from insurance companies and electronic medical records. Retrospective data are inherently limited, compared with prospective analyses, he said, and it’s possible that certain cases could be included in more than one database and thus be double-counted, whereas other cases could be missed entirely.

These findings also conflict with data from the United Kingdom, which in May reported that the average number of hepatitis cases had increased, compared with previous years, he said. More data are needed, he said, and he is involved with a study with the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that is also collecting data to try to understand whether there has been an uptick in pediatric hepatitis cases. The study will collect patient data directly from hospitals as well as include additional pathology data, such as biopsy results.

“We should not be inhibited to look further academically – and public health–wise – while we take into cognizance this very good, robust attempt from the CDC,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of pediatric hepatitis cases has remained steady since 2017, new research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests, despite the recent investigation into children with hepatitis of unknown cause. The study also found that there was no indication of elevated rates of adenovirus type 40/41 infection in children.

But Rohit Kohli, MBBS, MS, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, California, says that although the study is “well-designed and robust,” that does not mean that these hepatitis cases of unknown origin are no longer a concern. He was not involved with the CDC research. “As a clinician, I’m still worried,” he said. “Why I feel like this is not conclusive is that there are other data from entities like the United Kingdom Health Security Agency that are incongruent with [these findings],” he said.

The research was published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In November 2021, the Alabama Department of Public Health began an investigation with the CDC after a cluster of children were admitted to a children’s hospital in the state with severe hepatitis, who all tested positive for adenovirus. When the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency announced an investigation into similar cases in early April 2022, the CDC decided to expand their search nationally.

Now, as of June 15, the agency is investigating 290 cases in 41 states and U.S. territories. Worldwide, 650 cases in 33 countries have been reported, according to the most recent update by the World Health Organization on May 27, 2022. At least 38 patients have needed liver transplants, and nine deaths have been reported to WHO.

In its most recent press call on the topic, the CDC announced that it’s aware of six deaths in the United States through May 20, 2022. The COVID-19 vaccine has been ruled out as a potential cause because the majority of affected children are unvaccinated or are too young to receive the vaccine. Adenovirus infection remains a leading suspect in these sick children because the virus has been detected in 60.8% of tested cases, WHO reports.

Investigators have detected an increase in reported pediatric hepatitis cases, compared with prior years in the United Kingdom, but it was not clear whether that same pattern would be found in the United States. Neither pediatric hepatitis nor adenovirus type 40/41 are reportable conditions in the United States. In the May 20 CDC press call, Umesh Parashar, MD, chief of the CDC’s Viral Gastroenteritis Branch, said that an estimated 1,500-2,000 children aged younger than 10 are hospitalized in the United States for hepatitis every year. “That’s a fairly large number,” he said, and it might make it difficult to detect a small increase in cases.

To better estimate trends in pediatric hepatitis and adenovirus infection in the United States, investigators collected available data on emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants associated with hepatitis in children as well as adenovirus stool testing results. Researchers used four large databases: the National Syndromic Surveillance Program; the Premier Healthcare Database Special Release; the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network; and Labcorp, which is a large commercial lab network.

To account for changes in health care utilization in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the team compared hepatitis-associated ED visits, hospitalizations, and liver transplants from October 2021 to March 2022 versus the same months (January to March and October to December) in 2017, 2018, and 2019. For adenovirus stool testing, results from October 2021 to March 2022 were compared with the same calendar months (October to March) from 2017-2018, 2018-2019, and 2019-2020, to help control for seasonality.

Investigators found no statistically significant increases in the outcomes during October 2021 to March 2022 versus pre-pandemic years:

- Weekly ED visits with hepatitis-associated discharge codes

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalizations in children aged 0-4 years (22 vs. 19.5; P = .26)

- Hepatitis-associated monthly hospitalization in children aged 5-11 years (12 vs. 10.5; P = .42)

- Monthly liver transplants (5 vs. 4; P = .19)

- Percentage of stool specimens positive for adenovirus types 40/41, though the number of specimens tested was highest in March 2022

The authors acknowledged that pediatric hepatitis is rare, so it may be difficult tease out small changes in the number of cases. Also, data on hospitalizations and liver transplants have a 2- to 3-month reporting delay, so the case counts for March 2022 “might be underreported,” they wrote. Mr. Kohli noted that because hepatitis and adenovirus are not reportable conditions, the analysis relied on retrospective data from insurance companies and electronic medical records. Retrospective data are inherently limited, compared with prospective analyses, he said, and it’s possible that certain cases could be included in more than one database and thus be double-counted, whereas other cases could be missed entirely.

These findings also conflict with data from the United Kingdom, which in May reported that the average number of hepatitis cases had increased, compared with previous years, he said. More data are needed, he said, and he is involved with a study with the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases that is also collecting data to try to understand whether there has been an uptick in pediatric hepatitis cases. The study will collect patient data directly from hospitals as well as include additional pathology data, such as biopsy results.

“We should not be inhibited to look further academically – and public health–wise – while we take into cognizance this very good, robust attempt from the CDC,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MMWR

WHO to rename monkeypox because of stigma concerns

The virus has infected more than 1,600 people in 39 countries so far this year, the WHO said, including 32 countries where the virus isn’t typically detected.

“WHO is working with partners and experts from around the world on changing the name of monkeypox virus, its clades, and the disease it causes,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, the WHO’s director-general, said during a press briefing.

“We will make announcements about the new names as soon as possible,” he said.

Last week, more than 30 international scientists urged the public health community to change the name of the virus. The scientists posted a letter on June 10, which included support from the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, noting that the name should change with the ongoing transmission among humans this year.

“The prevailing perception in the international media and scientific literature is that MPXV is endemic in people in some African countries. However, it is well established that nearly all MPXV outbreaks in Africa prior to the 2022 outbreak have been the result of spillover from animals and humans and only rarely have there been reports of sustained human-to-human transmissions,” they wrote.

“In the context of the current global outbreak, continued reference to, and nomenclature of this virus being African is not only inaccurate but is also discriminatory and stigmatizing,” they added.

As one example, they noted, news outlets have used images of African patients to depict the pox lesions, although most stories about the current outbreak have focused on the global north. The Foreign Press Association of Africa has urged the global media to stop using images of Black people to highlight the outbreak in Europe.

“Although the origin of the new global MPXV outbreak is still unknown, there is growing evidence that the most likely scenario is that cross-continent, cryptic human transmission has been ongoing for longer than previously thought,” they wrote.

The WHO has listed two known clades of the monkeypox virus in recent updates – “one identified in West Africa and one in the Congo Basin region.” The group of scientists wrote that this approach is “counter to the best practice of avoiding geographic locations in the nomenclature of diseases and disease groups.”

The scientists proposed a new classification that would name three clades in order of detection – 1, 2, and 3 – for the viral genomes detected in Central Africa, Western Africa, and the localized spillover events detected this year in global north countries. More genome sequencing could uncover additional clades, they noted.

Even within the most recent clade, there is already notable diversity among the genomes, the scientists said. Like the new naming convention adopted for the coronavirus pandemic, the nomenclature for human monkeypox could be donated as “A.1, A.2, A.1.1,” they wrote.

The largest current outbreak is in the United Kingdom, where health officials have detected 524 cases, according to the latest update from the U.K. Health Security Agency.

As of June 15, 72 cases have been reported in the United States, including 15 in California and 15 in New York, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

Also on June 15, the WHO published interim guidance on the use of smallpox vaccines for monkeypox. The WHO doesn’t recommend mass vaccination against monkeypox and said vaccines should be used on a case-by-case basis.

The WHO will convene an emergency meeting next week to determine whether the spread of the virus should be considered a global public health emergency.

“The global outbreak of monkeypox is clearly unusual and concerning,” Dr. Tedros said June 15. “It’s for that reason that I have decided to convene the emergency committee under the International Health Regulations next week to assess whether this outbreak represents a public health emergency of international concern.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The virus has infected more than 1,600 people in 39 countries so far this year, the WHO said, including 32 countries where the virus isn’t typically detected.

“WHO is working with partners and experts from around the world on changing the name of monkeypox virus, its clades, and the disease it causes,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, the WHO’s director-general, said during a press briefing.

“We will make announcements about the new names as soon as possible,” he said.

Last week, more than 30 international scientists urged the public health community to change the name of the virus. The scientists posted a letter on June 10, which included support from the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, noting that the name should change with the ongoing transmission among humans this year.

“The prevailing perception in the international media and scientific literature is that MPXV is endemic in people in some African countries. However, it is well established that nearly all MPXV outbreaks in Africa prior to the 2022 outbreak have been the result of spillover from animals and humans and only rarely have there been reports of sustained human-to-human transmissions,” they wrote.

“In the context of the current global outbreak, continued reference to, and nomenclature of this virus being African is not only inaccurate but is also discriminatory and stigmatizing,” they added.

As one example, they noted, news outlets have used images of African patients to depict the pox lesions, although most stories about the current outbreak have focused on the global north. The Foreign Press Association of Africa has urged the global media to stop using images of Black people to highlight the outbreak in Europe.

“Although the origin of the new global MPXV outbreak is still unknown, there is growing evidence that the most likely scenario is that cross-continent, cryptic human transmission has been ongoing for longer than previously thought,” they wrote.

The WHO has listed two known clades of the monkeypox virus in recent updates – “one identified in West Africa and one in the Congo Basin region.” The group of scientists wrote that this approach is “counter to the best practice of avoiding geographic locations in the nomenclature of diseases and disease groups.”

The scientists proposed a new classification that would name three clades in order of detection – 1, 2, and 3 – for the viral genomes detected in Central Africa, Western Africa, and the localized spillover events detected this year in global north countries. More genome sequencing could uncover additional clades, they noted.

Even within the most recent clade, there is already notable diversity among the genomes, the scientists said. Like the new naming convention adopted for the coronavirus pandemic, the nomenclature for human monkeypox could be donated as “A.1, A.2, A.1.1,” they wrote.

The largest current outbreak is in the United Kingdom, where health officials have detected 524 cases, according to the latest update from the U.K. Health Security Agency.

As of June 15, 72 cases have been reported in the United States, including 15 in California and 15 in New York, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

Also on June 15, the WHO published interim guidance on the use of smallpox vaccines for monkeypox. The WHO doesn’t recommend mass vaccination against monkeypox and said vaccines should be used on a case-by-case basis.

The WHO will convene an emergency meeting next week to determine whether the spread of the virus should be considered a global public health emergency.

“The global outbreak of monkeypox is clearly unusual and concerning,” Dr. Tedros said June 15. “It’s for that reason that I have decided to convene the emergency committee under the International Health Regulations next week to assess whether this outbreak represents a public health emergency of international concern.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The virus has infected more than 1,600 people in 39 countries so far this year, the WHO said, including 32 countries where the virus isn’t typically detected.

“WHO is working with partners and experts from around the world on changing the name of monkeypox virus, its clades, and the disease it causes,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, PhD, the WHO’s director-general, said during a press briefing.

“We will make announcements about the new names as soon as possible,” he said.

Last week, more than 30 international scientists urged the public health community to change the name of the virus. The scientists posted a letter on June 10, which included support from the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, noting that the name should change with the ongoing transmission among humans this year.

“The prevailing perception in the international media and scientific literature is that MPXV is endemic in people in some African countries. However, it is well established that nearly all MPXV outbreaks in Africa prior to the 2022 outbreak have been the result of spillover from animals and humans and only rarely have there been reports of sustained human-to-human transmissions,” they wrote.

“In the context of the current global outbreak, continued reference to, and nomenclature of this virus being African is not only inaccurate but is also discriminatory and stigmatizing,” they added.

As one example, they noted, news outlets have used images of African patients to depict the pox lesions, although most stories about the current outbreak have focused on the global north. The Foreign Press Association of Africa has urged the global media to stop using images of Black people to highlight the outbreak in Europe.

“Although the origin of the new global MPXV outbreak is still unknown, there is growing evidence that the most likely scenario is that cross-continent, cryptic human transmission has been ongoing for longer than previously thought,” they wrote.

The WHO has listed two known clades of the monkeypox virus in recent updates – “one identified in West Africa and one in the Congo Basin region.” The group of scientists wrote that this approach is “counter to the best practice of avoiding geographic locations in the nomenclature of diseases and disease groups.”

The scientists proposed a new classification that would name three clades in order of detection – 1, 2, and 3 – for the viral genomes detected in Central Africa, Western Africa, and the localized spillover events detected this year in global north countries. More genome sequencing could uncover additional clades, they noted.

Even within the most recent clade, there is already notable diversity among the genomes, the scientists said. Like the new naming convention adopted for the coronavirus pandemic, the nomenclature for human monkeypox could be donated as “A.1, A.2, A.1.1,” they wrote.

The largest current outbreak is in the United Kingdom, where health officials have detected 524 cases, according to the latest update from the U.K. Health Security Agency.

As of June 15, 72 cases have been reported in the United States, including 15 in California and 15 in New York, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

Also on June 15, the WHO published interim guidance on the use of smallpox vaccines for monkeypox. The WHO doesn’t recommend mass vaccination against monkeypox and said vaccines should be used on a case-by-case basis.

The WHO will convene an emergency meeting next week to determine whether the spread of the virus should be considered a global public health emergency.

“The global outbreak of monkeypox is clearly unusual and concerning,” Dr. Tedros said June 15. “It’s for that reason that I have decided to convene the emergency committee under the International Health Regulations next week to assess whether this outbreak represents a public health emergency of international concern.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Blood test aims to measure COVID immunity

Scientists created a test that indirectly measures T-cell response – an important, long-term component of immunity that can last long after antibody levels fall off – to a challenge by the virus in whole blood.

The test mimics what can be done in a formal laboratory now but avoids some complicated steps and specialized training for lab personnel. This test, researchers said, is faster, can scale up to test many more people, and can be adapted to detect viral mutations as they emerge in the future.

The study explaining how all this works was published online in Nature Biotechnology.

The test, called dqTACT, could help predict the likelihood of “breakthrough” infections in people who are fully vaccinated and could help determine how frequently people who are immunocompromised might need to be revaccinated, the authors noted.

Infection with the coronavirus and other viruses can trigger a one-two punch from the immunity system – a fast antibody response followed by longer-lasting cellular immunity, including T cells, which “remember” the virus. Cellular immunity can trigger a quick response if the same virus ever shows up again.

The new test adds synthetic viral peptides – strings of amino acids that make up proteins – from the coronavirus to a blood sample. If there is no T-cell reaction within 24 hours, the test is negative. If the peptides trigger T cells, the test can measure the strength of the immune response.

The researchers validated the new test against traditional laboratory testing in 91 people, about half of whom never had COVID-19 and another half who were infected and recovered. The results matched well.

They also found the test predicted immune strength up to 8 months following a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, T-cell response was greater among people who received two doses of a vaccine versus others who received only one immunization.

Studies are ongoing and designed to meet authorization requirements as part of future licensing from the Food and Drug Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Scientists created a test that indirectly measures T-cell response – an important, long-term component of immunity that can last long after antibody levels fall off – to a challenge by the virus in whole blood.

The test mimics what can be done in a formal laboratory now but avoids some complicated steps and specialized training for lab personnel. This test, researchers said, is faster, can scale up to test many more people, and can be adapted to detect viral mutations as they emerge in the future.

The study explaining how all this works was published online in Nature Biotechnology.

The test, called dqTACT, could help predict the likelihood of “breakthrough” infections in people who are fully vaccinated and could help determine how frequently people who are immunocompromised might need to be revaccinated, the authors noted.

Infection with the coronavirus and other viruses can trigger a one-two punch from the immunity system – a fast antibody response followed by longer-lasting cellular immunity, including T cells, which “remember” the virus. Cellular immunity can trigger a quick response if the same virus ever shows up again.

The new test adds synthetic viral peptides – strings of amino acids that make up proteins – from the coronavirus to a blood sample. If there is no T-cell reaction within 24 hours, the test is negative. If the peptides trigger T cells, the test can measure the strength of the immune response.

The researchers validated the new test against traditional laboratory testing in 91 people, about half of whom never had COVID-19 and another half who were infected and recovered. The results matched well.

They also found the test predicted immune strength up to 8 months following a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, T-cell response was greater among people who received two doses of a vaccine versus others who received only one immunization.

Studies are ongoing and designed to meet authorization requirements as part of future licensing from the Food and Drug Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Scientists created a test that indirectly measures T-cell response – an important, long-term component of immunity that can last long after antibody levels fall off – to a challenge by the virus in whole blood.

The test mimics what can be done in a formal laboratory now but avoids some complicated steps and specialized training for lab personnel. This test, researchers said, is faster, can scale up to test many more people, and can be adapted to detect viral mutations as they emerge in the future.

The study explaining how all this works was published online in Nature Biotechnology.

The test, called dqTACT, could help predict the likelihood of “breakthrough” infections in people who are fully vaccinated and could help determine how frequently people who are immunocompromised might need to be revaccinated, the authors noted.

Infection with the coronavirus and other viruses can trigger a one-two punch from the immunity system – a fast antibody response followed by longer-lasting cellular immunity, including T cells, which “remember” the virus. Cellular immunity can trigger a quick response if the same virus ever shows up again.

The new test adds synthetic viral peptides – strings of amino acids that make up proteins – from the coronavirus to a blood sample. If there is no T-cell reaction within 24 hours, the test is negative. If the peptides trigger T cells, the test can measure the strength of the immune response.

The researchers validated the new test against traditional laboratory testing in 91 people, about half of whom never had COVID-19 and another half who were infected and recovered. The results matched well.

They also found the test predicted immune strength up to 8 months following a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, T-cell response was greater among people who received two doses of a vaccine versus others who received only one immunization.

Studies are ongoing and designed to meet authorization requirements as part of future licensing from the Food and Drug Administration.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY

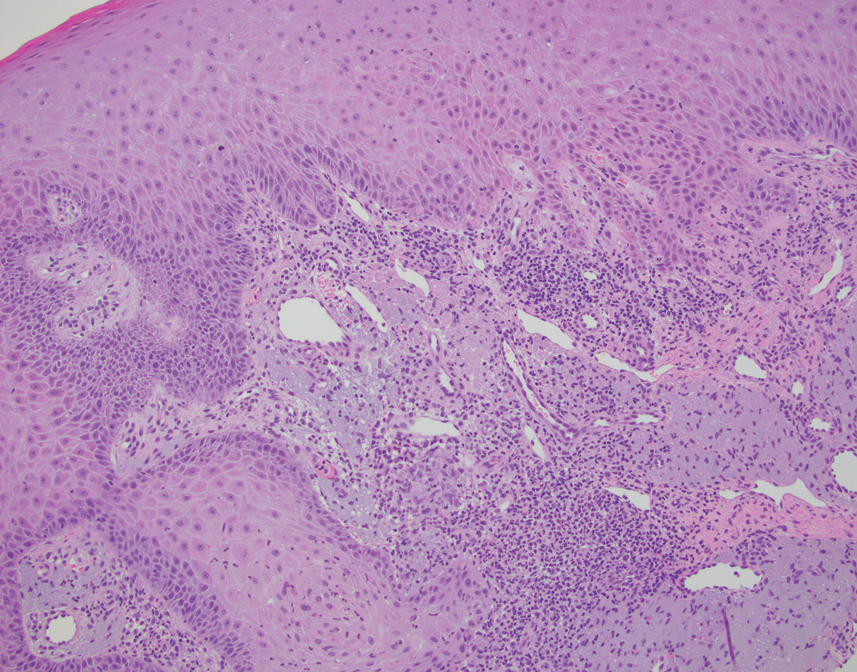

A Hispanic male presented with a 3-month history of a spreading, itchy rash

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, more often on exposed skin. In the United States, Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and Microsporum canis are the most common causal organisms. People can become infected from contact with other people, animals, or soil. Variants of tinea corporis include tinea imbricata (caused by T. concentricum), bullous tinea corporis, tinea gladiatorum (seen in wrestlers), tinea incognito (atypical tinea resulting from topical steroid use), and Majocchi’s granuloma. Widespread tinea may be secondary to underlying immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS or treatment with topical or oral steroids.

The typical presentation of tinea corporis is scaly erythematous or hypopigmented annular patches with a raised border and central clearing. In tinea imbricata, which is more commonly seen in southeast Asia, India, and Central America, concentric circles and serpiginous plaques are present. Majocchi’s granuloma has a deeper involvement of fungus in the hair follicles, presenting with papules and pustules at the periphery of the patches. Lesions of tinea incognito may lack a scaly border and can be more widespread.

Diagnosis can be confirmed with a skin scraping and potassium hydroxide (KOH) staining, which will reveal septate and branching hyphae. Biopsy is often helpful, especially in tinea incognito. Classically, a “sandwich sign” is seen: hyphae between orthokeratosis and compact hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis. In this patient, a biopsy from the left hip revealed dermatophytosis, with PAS positive for organisms.

Localized lesions respond to topical antifungal creams such as azoles or topical terbinafine. More extensive tinea will often require a systemic antifungal with griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, or fluconazole. This patient responded to topical ketoconazole cream and oral terbinafine. A workup for underlying immunodeficiency was negative.

Dr. Bilu Martin provided this case and photo.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Is hepatitis C an STI?

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at imnews@mdedge.com.

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at imnews@mdedge.com.

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at imnews@mdedge.com.

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

Nonhealing Violaceous Plaque of the Hand Following a Splinter Injury

The Diagnosis: Chromoblastomycosis

This case highlights the importance of routine skin biopsy and tissue culture when clinical suspicion for mycotic infection is high. Despite nonspecific biopsy results (Figure), a diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis (CBM) was reached based on tissue culture. Surgical excision was not possible in our patient due to the size and location of the lesion. The patient was referred to infectious disease, with the plan to start long-term itraconazole for at least 6 to 12 months.

Cases of CBM were first documented in 1914 and distinguished by the appearance of spherical, brown, muriform cells on skin biopsy—features that now serve as the hallmark of CBM diagnoses.1,2 The implantation mycosis commonly is caused by agents such as Fonsecaea pedrosoi and Fonsecaea monophora of the bantiana-clade, as classified according to molecular phylogeny2; these agents have been isolated from soil, plants, and wood sources in tropical and subtropical regions and are strongly associated with agricultural activities.3

Chromoblastomycosis lesions tend to be asymptomatic with a variable amount of time between inoculation and lesion presentation, delaying medical care by months to years.3 The fungus causes a granulomatous reaction after skin damage, with noticeable pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis and granulomas formed by epithelioid and Langerhans cells in the dermis.4 Typically, CBM initially presents as an erythematous macular skin lesion, which then progresses to become more pink, papular, and sometimes pruritic.2 Muriform (sclerotic) bodies, which reflect fungal components, extrude transepidermally and appear as black dots on the lesion’s surface.4 Chromoblastomycosis is limited to the subcutaneous tissue and has been classified into 5 types of lesions: nodular, tumoral, verrucous, scarring, and plaque.2 Diagnosis is established using fungal tests such as potassium hydroxide direct microscopy, which exposes muriform bodies often in combination with dematiaceous hyphae, while fungal culture of F pedrosoi in Sabouraud agar produces velvety dark colonies.3 Although an immune response to CBM infection remains unclear, it has been demonstrated that the response differs based on the severity of the infection. The severe form of CBM produces high levels of IL-10, low levels of IFN-γ, and inefficient T-cell proliferation, while milder forms of CBM display low levels of IL-10, high levels of IFN-γ, and efficient T-cell proliferation.5 Complications of CBM include chronic lymphedema, ankylosis, and secondary bacterial infections, which largely are observed in advanced cases; malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma, though rare, also has been observed.6