User login

Medicare faces calls to stop physician pay cuts in E/M overhaul

A planned overhaul of reimbursement for evaluation and management (E/M) services emerged as perhaps the most contentious issue connected to Medicare’s 2021 payment policies for clinicians.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included the planned E/M overhaul — and accompanying offsets — in the draft 2021 physician fee schedule, released in August. The draft fee schedule drew at least 45,675 responses by October 5, the deadline for offering comments, with many of the responses addressing the E/M overhaul.

The influential Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) “strongly” endorsed the “budget-neutral” approach taken with the E/M overhaul. This planned reshuffling of payments is a step toward addressing a shortfall of primary care clinicians, inasmuch as it would help make this field more financially appealing, MedPAC said in an October 2 letter to CMS.

In contrast, physician organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), asked CMS to waive or revise the budget-neutral aspect of the E/M overhaul. Among the specialties slated for reductions are those deeply involved with the response to the pandemic, wrote James L. Madara, AMA’s chief executive officer, in an October 5 comment to CMS. Emergency medicine as a field would see a 6% cut, and infectious disease specialists, a 4% reduction.

“Payment reductions of this magnitude would be a major problem at any time, but to impose cuts of this magnitude during or immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, including steep cuts to many of the specialties that have been on the front lines in efforts to treat patients in places with widespread infection, is unconscionable,” Madara wrote.

Madara also said specialties scheduled for payment reductions include those least able to make up for the lack of in-person care as a result of the uptick in telehealth during the pandemic.

A chart in the draft physician fee schedule (Table 90) shows reductions for many specialties that do not routinely bill for office visits. The table shows an 8% cut for anesthesiologists, a 7% cut for general surgeons, and a 6% cut for ophthalmologists. Table 90 also shows an estimated 11% reduction for radiologists and a 9% drop for pathologists.

The draft rule notes that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services, so they may not reflect what any particular clinician might receive.

In total, Table 90 shows how the E/M changes and connected offsets would affect more than 50 fields of medicine. The proposal includes a 17% expected increase for endocrinologists and a 14% bump for those in hematology/oncology. There are expected increases of 13% for family practice and 4% for internal medicine.

This reshuffling of payments among specialties is only part of the 2021 E/M overhaul. There’s strong support for other aspects, making it unlikely that CMS would consider dropping the plan entirely.

“CMS’ new office visit policy will lead to significant administrative burden reduction and will better describe and recognize the resources involved in clinical office visits as they are performed today,” AMA’s Madara wrote in his comment.

Changes for the billing framework for E/M slated to start in 2021 are the result of substantial collaboration by an AMA-convened work group, which brought together more than 170 state medical and specialty societies, Madara said in his comment.

CMS has been developing this plan for several years. It outlined this 2021 E/M overhaul in the 2020 Medicare physician fee schedule finalized last year.

Madara urged CMS to proceed with the E/M changes but also “exercise the full breadth and depth of its administrative authority” to avoid or minimize the planned cuts.

“To be clear, we are not asking CMS to phase in implementation of the E/M changes but rather to phase in the payment reductions for certain specialties and health professionals in 2021 due to budget neutrality,” he wrote.

Other groups asking CMS to waive the budget-neutrality requirement include the American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) asked CMS to temporarily waive the budget-neutrality requirement and pressed the agency to maintain the underlying principle of the E/M overhaul.

“Should HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] use its authority to waive budget neutrality, we also recommend that CMS finalize a reinstatement plan for the conversion factor reductions that provides physician practices with ample time to prepare and does not result in a financial cliff,” wrote John S. Cullen, MD, board chair for AAFP, in a September 28 comment to CMS.

Owing to the declaration of a public health emergency, HHS could use a special provision known as 1135 waiver authority to waive budget-neutrality requirements, Cullen wrote.

“The AAFP understands that HHS’ authority is limited by the timing of the end of the public health emergency, but we believe that this approach will provide Congress with needed time to enact an accompanying legislative solution,” he wrote.

Lawmakers weigh in

Lawmakers in both political parties have asked CMS to reconsider the offsets in the E/M overhaul.

Rep. Michael C. Burgess, MD (R-TX), who practiced as an obstetrician before joining Congress, in October introduced a bill with Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) that would provide for a 1-year waiver of budget-neutrality adjustments under the Medicare physician fee schedule.

Burgess and Rush were among the more than 160 members of Congress who signed a September letter to CMS asking the agency to act on its own to drop the budget-neutrality requirement. In the letter, led by Rep. Roger Marshall, MD (R-KS), the lawmakers acknowledge the usual legal requirements for CMS to offset payment increases in the physician fee schedule with cuts. But the lawmakers said the national public health emergency allows CMS to work around this.

“Given the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe you have the regulatory authority to immediately address these inequities,” the lawmakers wrote. “There is also the need to consider how the outbreak will be in the fall/winter months and if postponing certain elective procedures will go back into effect, per CMS’ recommendations.

“While we understand that legislative action may also be required to address this issue, given the January 1, 2021 effective date, we would ask you to take immediate actions to delay or mitigate these cuts while allowing the scheduled increases to go into effect,” the lawmakers said in closing their letter. “This approach will give Congress sufficient time to develop a meaningful solution and to address these looming needs.”

Another option might be for CMS to preserve the budget-neutrality claim for the 2021 physician fee schedule but soften the blow on specialties, Brian Fortune, president of the consulting firm Farragut Square Group, told Medscape Medical News. A former staffer for Republican leadership in the House of Representatives, Fortune has for more than 20 years followed Medicare policy.

The agency could redo some of the assumptions used in estimating the offsets, he said, adding that in the draft rule, CMS appears to be seeking feedback that could help it with new calculations.

“CMS has been looking for a way out,” Fortune said. “CMS could remodel the assumptions, and the cuts could drop by half or more.

“The agency has several options to get creative as the need arises,” he said.

“Overvalued” vs “devalued”

In its comment to CMS, though, MedPAC argued strongly for maintaining the offsets. The commission has for several years been investigating ways to use Medicare’s payment policies as a tool to boost the ranks of clinicians who provide primary care.

A reshuffling of payments among specialties is needed to address a known imbalance in which Medicare for many years has “overvalued” procedures at the expense of other medical care, wrote Michael E. Chernew, PhD, the chairman of MedPAC, in an October 2 comment to CMS.

“Some types of services — such as procedures, imaging, and tests — experience efficiency gains over time, as advances in technology, technique, and clinical practice enable clinicians to deliver them faster,” he wrote. “However, E&M office/outpatient visits do not lend themselves to such efficiency gains because they consist largely of activities that require the clinician’s time.”

Medicare’s payment policies have thus “passively devalued” the time many clinicians spend on office visits, helping to skew the decisions of young physicians toward specialties, according to Chernew.

Reshuffling payment away from specialties that are now “overvalued” is needed to “remedy several years of passive devaluation,” he wrote.

The median income in 2018 for primary care physicians was $243,000 in 2018, whereas that of specialists such as surgeons was $426,000, Chernew said in the letter, citing MedPAC research.

These figures echo the findings of Medscape’s most recent annual physician compensation report.

As one of the largest buyers of medical services, Medicare has significant influence on the practice of medicine in the United States. In 2018 alone, Medicare directly paid $70.5 billion for clinician services. Its payment policies already may have shaped the pool of clinicians available to treat people enrolled in Medicare, which covers those aged 65 years and older, Chernew said.

“The US has over three times as many specialists as primary care physicians, which could explain why MedPAC’s annual survey of Medicare beneficiaries has repeatedly found that beneficiaries who are looking for a new physician report having an easier time finding a new specialist than a new primary care provider,” he wrote.

“Access to primary care physicians could worsen in the future as the number of primary care physicians in the US, after remaining flat for several years, has actually started to decline,” Chernew said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A planned overhaul of reimbursement for evaluation and management (E/M) services emerged as perhaps the most contentious issue connected to Medicare’s 2021 payment policies for clinicians.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included the planned E/M overhaul — and accompanying offsets — in the draft 2021 physician fee schedule, released in August. The draft fee schedule drew at least 45,675 responses by October 5, the deadline for offering comments, with many of the responses addressing the E/M overhaul.

The influential Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) “strongly” endorsed the “budget-neutral” approach taken with the E/M overhaul. This planned reshuffling of payments is a step toward addressing a shortfall of primary care clinicians, inasmuch as it would help make this field more financially appealing, MedPAC said in an October 2 letter to CMS.

In contrast, physician organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), asked CMS to waive or revise the budget-neutral aspect of the E/M overhaul. Among the specialties slated for reductions are those deeply involved with the response to the pandemic, wrote James L. Madara, AMA’s chief executive officer, in an October 5 comment to CMS. Emergency medicine as a field would see a 6% cut, and infectious disease specialists, a 4% reduction.

“Payment reductions of this magnitude would be a major problem at any time, but to impose cuts of this magnitude during or immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, including steep cuts to many of the specialties that have been on the front lines in efforts to treat patients in places with widespread infection, is unconscionable,” Madara wrote.

Madara also said specialties scheduled for payment reductions include those least able to make up for the lack of in-person care as a result of the uptick in telehealth during the pandemic.

A chart in the draft physician fee schedule (Table 90) shows reductions for many specialties that do not routinely bill for office visits. The table shows an 8% cut for anesthesiologists, a 7% cut for general surgeons, and a 6% cut for ophthalmologists. Table 90 also shows an estimated 11% reduction for radiologists and a 9% drop for pathologists.

The draft rule notes that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services, so they may not reflect what any particular clinician might receive.

In total, Table 90 shows how the E/M changes and connected offsets would affect more than 50 fields of medicine. The proposal includes a 17% expected increase for endocrinologists and a 14% bump for those in hematology/oncology. There are expected increases of 13% for family practice and 4% for internal medicine.

This reshuffling of payments among specialties is only part of the 2021 E/M overhaul. There’s strong support for other aspects, making it unlikely that CMS would consider dropping the plan entirely.

“CMS’ new office visit policy will lead to significant administrative burden reduction and will better describe and recognize the resources involved in clinical office visits as they are performed today,” AMA’s Madara wrote in his comment.

Changes for the billing framework for E/M slated to start in 2021 are the result of substantial collaboration by an AMA-convened work group, which brought together more than 170 state medical and specialty societies, Madara said in his comment.

CMS has been developing this plan for several years. It outlined this 2021 E/M overhaul in the 2020 Medicare physician fee schedule finalized last year.

Madara urged CMS to proceed with the E/M changes but also “exercise the full breadth and depth of its administrative authority” to avoid or minimize the planned cuts.

“To be clear, we are not asking CMS to phase in implementation of the E/M changes but rather to phase in the payment reductions for certain specialties and health professionals in 2021 due to budget neutrality,” he wrote.

Other groups asking CMS to waive the budget-neutrality requirement include the American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) asked CMS to temporarily waive the budget-neutrality requirement and pressed the agency to maintain the underlying principle of the E/M overhaul.

“Should HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] use its authority to waive budget neutrality, we also recommend that CMS finalize a reinstatement plan for the conversion factor reductions that provides physician practices with ample time to prepare and does not result in a financial cliff,” wrote John S. Cullen, MD, board chair for AAFP, in a September 28 comment to CMS.

Owing to the declaration of a public health emergency, HHS could use a special provision known as 1135 waiver authority to waive budget-neutrality requirements, Cullen wrote.

“The AAFP understands that HHS’ authority is limited by the timing of the end of the public health emergency, but we believe that this approach will provide Congress with needed time to enact an accompanying legislative solution,” he wrote.

Lawmakers weigh in

Lawmakers in both political parties have asked CMS to reconsider the offsets in the E/M overhaul.

Rep. Michael C. Burgess, MD (R-TX), who practiced as an obstetrician before joining Congress, in October introduced a bill with Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) that would provide for a 1-year waiver of budget-neutrality adjustments under the Medicare physician fee schedule.

Burgess and Rush were among the more than 160 members of Congress who signed a September letter to CMS asking the agency to act on its own to drop the budget-neutrality requirement. In the letter, led by Rep. Roger Marshall, MD (R-KS), the lawmakers acknowledge the usual legal requirements for CMS to offset payment increases in the physician fee schedule with cuts. But the lawmakers said the national public health emergency allows CMS to work around this.

“Given the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe you have the regulatory authority to immediately address these inequities,” the lawmakers wrote. “There is also the need to consider how the outbreak will be in the fall/winter months and if postponing certain elective procedures will go back into effect, per CMS’ recommendations.

“While we understand that legislative action may also be required to address this issue, given the January 1, 2021 effective date, we would ask you to take immediate actions to delay or mitigate these cuts while allowing the scheduled increases to go into effect,” the lawmakers said in closing their letter. “This approach will give Congress sufficient time to develop a meaningful solution and to address these looming needs.”

Another option might be for CMS to preserve the budget-neutrality claim for the 2021 physician fee schedule but soften the blow on specialties, Brian Fortune, president of the consulting firm Farragut Square Group, told Medscape Medical News. A former staffer for Republican leadership in the House of Representatives, Fortune has for more than 20 years followed Medicare policy.

The agency could redo some of the assumptions used in estimating the offsets, he said, adding that in the draft rule, CMS appears to be seeking feedback that could help it with new calculations.

“CMS has been looking for a way out,” Fortune said. “CMS could remodel the assumptions, and the cuts could drop by half or more.

“The agency has several options to get creative as the need arises,” he said.

“Overvalued” vs “devalued”

In its comment to CMS, though, MedPAC argued strongly for maintaining the offsets. The commission has for several years been investigating ways to use Medicare’s payment policies as a tool to boost the ranks of clinicians who provide primary care.

A reshuffling of payments among specialties is needed to address a known imbalance in which Medicare for many years has “overvalued” procedures at the expense of other medical care, wrote Michael E. Chernew, PhD, the chairman of MedPAC, in an October 2 comment to CMS.

“Some types of services — such as procedures, imaging, and tests — experience efficiency gains over time, as advances in technology, technique, and clinical practice enable clinicians to deliver them faster,” he wrote. “However, E&M office/outpatient visits do not lend themselves to such efficiency gains because they consist largely of activities that require the clinician’s time.”

Medicare’s payment policies have thus “passively devalued” the time many clinicians spend on office visits, helping to skew the decisions of young physicians toward specialties, according to Chernew.

Reshuffling payment away from specialties that are now “overvalued” is needed to “remedy several years of passive devaluation,” he wrote.

The median income in 2018 for primary care physicians was $243,000 in 2018, whereas that of specialists such as surgeons was $426,000, Chernew said in the letter, citing MedPAC research.

These figures echo the findings of Medscape’s most recent annual physician compensation report.

As one of the largest buyers of medical services, Medicare has significant influence on the practice of medicine in the United States. In 2018 alone, Medicare directly paid $70.5 billion for clinician services. Its payment policies already may have shaped the pool of clinicians available to treat people enrolled in Medicare, which covers those aged 65 years and older, Chernew said.

“The US has over three times as many specialists as primary care physicians, which could explain why MedPAC’s annual survey of Medicare beneficiaries has repeatedly found that beneficiaries who are looking for a new physician report having an easier time finding a new specialist than a new primary care provider,” he wrote.

“Access to primary care physicians could worsen in the future as the number of primary care physicians in the US, after remaining flat for several years, has actually started to decline,” Chernew said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A planned overhaul of reimbursement for evaluation and management (E/M) services emerged as perhaps the most contentious issue connected to Medicare’s 2021 payment policies for clinicians.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included the planned E/M overhaul — and accompanying offsets — in the draft 2021 physician fee schedule, released in August. The draft fee schedule drew at least 45,675 responses by October 5, the deadline for offering comments, with many of the responses addressing the E/M overhaul.

The influential Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) “strongly” endorsed the “budget-neutral” approach taken with the E/M overhaul. This planned reshuffling of payments is a step toward addressing a shortfall of primary care clinicians, inasmuch as it would help make this field more financially appealing, MedPAC said in an October 2 letter to CMS.

In contrast, physician organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), asked CMS to waive or revise the budget-neutral aspect of the E/M overhaul. Among the specialties slated for reductions are those deeply involved with the response to the pandemic, wrote James L. Madara, AMA’s chief executive officer, in an October 5 comment to CMS. Emergency medicine as a field would see a 6% cut, and infectious disease specialists, a 4% reduction.

“Payment reductions of this magnitude would be a major problem at any time, but to impose cuts of this magnitude during or immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic, including steep cuts to many of the specialties that have been on the front lines in efforts to treat patients in places with widespread infection, is unconscionable,” Madara wrote.

Madara also said specialties scheduled for payment reductions include those least able to make up for the lack of in-person care as a result of the uptick in telehealth during the pandemic.

A chart in the draft physician fee schedule (Table 90) shows reductions for many specialties that do not routinely bill for office visits. The table shows an 8% cut for anesthesiologists, a 7% cut for general surgeons, and a 6% cut for ophthalmologists. Table 90 also shows an estimated 11% reduction for radiologists and a 9% drop for pathologists.

The draft rule notes that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services, so they may not reflect what any particular clinician might receive.

In total, Table 90 shows how the E/M changes and connected offsets would affect more than 50 fields of medicine. The proposal includes a 17% expected increase for endocrinologists and a 14% bump for those in hematology/oncology. There are expected increases of 13% for family practice and 4% for internal medicine.

This reshuffling of payments among specialties is only part of the 2021 E/M overhaul. There’s strong support for other aspects, making it unlikely that CMS would consider dropping the plan entirely.

“CMS’ new office visit policy will lead to significant administrative burden reduction and will better describe and recognize the resources involved in clinical office visits as they are performed today,” AMA’s Madara wrote in his comment.

Changes for the billing framework for E/M slated to start in 2021 are the result of substantial collaboration by an AMA-convened work group, which brought together more than 170 state medical and specialty societies, Madara said in his comment.

CMS has been developing this plan for several years. It outlined this 2021 E/M overhaul in the 2020 Medicare physician fee schedule finalized last year.

Madara urged CMS to proceed with the E/M changes but also “exercise the full breadth and depth of its administrative authority” to avoid or minimize the planned cuts.

“To be clear, we are not asking CMS to phase in implementation of the E/M changes but rather to phase in the payment reductions for certain specialties and health professionals in 2021 due to budget neutrality,” he wrote.

Other groups asking CMS to waive the budget-neutrality requirement include the American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the American Society of Neuroradiology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) asked CMS to temporarily waive the budget-neutrality requirement and pressed the agency to maintain the underlying principle of the E/M overhaul.

“Should HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] use its authority to waive budget neutrality, we also recommend that CMS finalize a reinstatement plan for the conversion factor reductions that provides physician practices with ample time to prepare and does not result in a financial cliff,” wrote John S. Cullen, MD, board chair for AAFP, in a September 28 comment to CMS.

Owing to the declaration of a public health emergency, HHS could use a special provision known as 1135 waiver authority to waive budget-neutrality requirements, Cullen wrote.

“The AAFP understands that HHS’ authority is limited by the timing of the end of the public health emergency, but we believe that this approach will provide Congress with needed time to enact an accompanying legislative solution,” he wrote.

Lawmakers weigh in

Lawmakers in both political parties have asked CMS to reconsider the offsets in the E/M overhaul.

Rep. Michael C. Burgess, MD (R-TX), who practiced as an obstetrician before joining Congress, in October introduced a bill with Rep. Bobby Rush (D-IL) that would provide for a 1-year waiver of budget-neutrality adjustments under the Medicare physician fee schedule.

Burgess and Rush were among the more than 160 members of Congress who signed a September letter to CMS asking the agency to act on its own to drop the budget-neutrality requirement. In the letter, led by Rep. Roger Marshall, MD (R-KS), the lawmakers acknowledge the usual legal requirements for CMS to offset payment increases in the physician fee schedule with cuts. But the lawmakers said the national public health emergency allows CMS to work around this.

“Given the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe you have the regulatory authority to immediately address these inequities,” the lawmakers wrote. “There is also the need to consider how the outbreak will be in the fall/winter months and if postponing certain elective procedures will go back into effect, per CMS’ recommendations.

“While we understand that legislative action may also be required to address this issue, given the January 1, 2021 effective date, we would ask you to take immediate actions to delay or mitigate these cuts while allowing the scheduled increases to go into effect,” the lawmakers said in closing their letter. “This approach will give Congress sufficient time to develop a meaningful solution and to address these looming needs.”

Another option might be for CMS to preserve the budget-neutrality claim for the 2021 physician fee schedule but soften the blow on specialties, Brian Fortune, president of the consulting firm Farragut Square Group, told Medscape Medical News. A former staffer for Republican leadership in the House of Representatives, Fortune has for more than 20 years followed Medicare policy.

The agency could redo some of the assumptions used in estimating the offsets, he said, adding that in the draft rule, CMS appears to be seeking feedback that could help it with new calculations.

“CMS has been looking for a way out,” Fortune said. “CMS could remodel the assumptions, and the cuts could drop by half or more.

“The agency has several options to get creative as the need arises,” he said.

“Overvalued” vs “devalued”

In its comment to CMS, though, MedPAC argued strongly for maintaining the offsets. The commission has for several years been investigating ways to use Medicare’s payment policies as a tool to boost the ranks of clinicians who provide primary care.

A reshuffling of payments among specialties is needed to address a known imbalance in which Medicare for many years has “overvalued” procedures at the expense of other medical care, wrote Michael E. Chernew, PhD, the chairman of MedPAC, in an October 2 comment to CMS.

“Some types of services — such as procedures, imaging, and tests — experience efficiency gains over time, as advances in technology, technique, and clinical practice enable clinicians to deliver them faster,” he wrote. “However, E&M office/outpatient visits do not lend themselves to such efficiency gains because they consist largely of activities that require the clinician’s time.”

Medicare’s payment policies have thus “passively devalued” the time many clinicians spend on office visits, helping to skew the decisions of young physicians toward specialties, according to Chernew.

Reshuffling payment away from specialties that are now “overvalued” is needed to “remedy several years of passive devaluation,” he wrote.

The median income in 2018 for primary care physicians was $243,000 in 2018, whereas that of specialists such as surgeons was $426,000, Chernew said in the letter, citing MedPAC research.

These figures echo the findings of Medscape’s most recent annual physician compensation report.

As one of the largest buyers of medical services, Medicare has significant influence on the practice of medicine in the United States. In 2018 alone, Medicare directly paid $70.5 billion for clinician services. Its payment policies already may have shaped the pool of clinicians available to treat people enrolled in Medicare, which covers those aged 65 years and older, Chernew said.

“The US has over three times as many specialists as primary care physicians, which could explain why MedPAC’s annual survey of Medicare beneficiaries has repeatedly found that beneficiaries who are looking for a new physician report having an easier time finding a new specialist than a new primary care provider,” he wrote.

“Access to primary care physicians could worsen in the future as the number of primary care physicians in the US, after remaining flat for several years, has actually started to decline,” Chernew said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

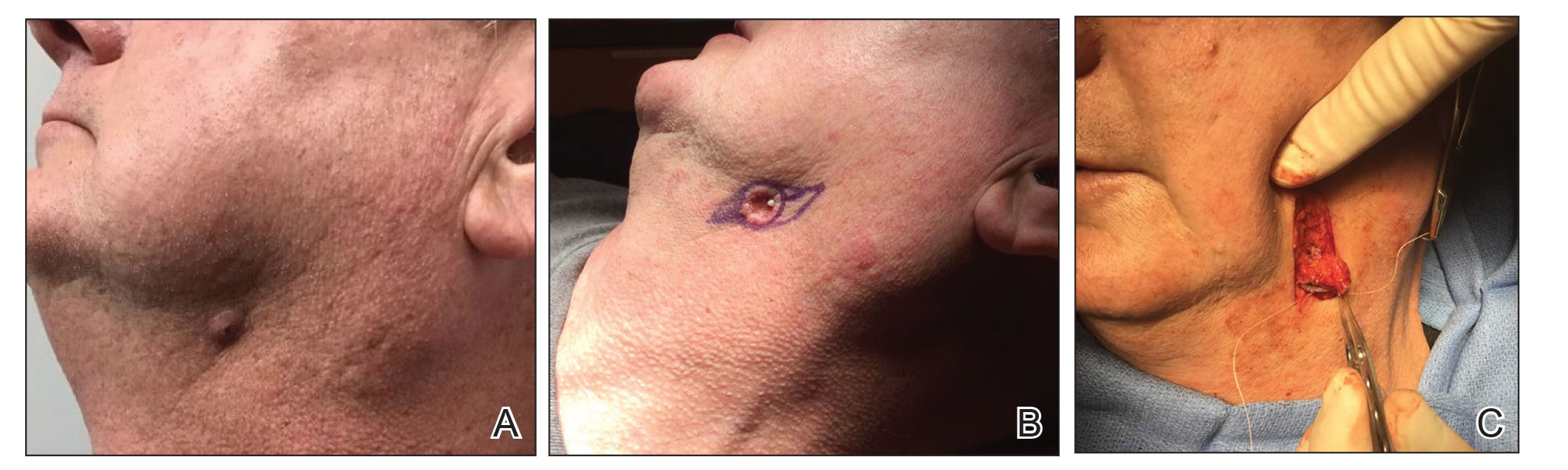

Irritated Pigmented Plaque on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

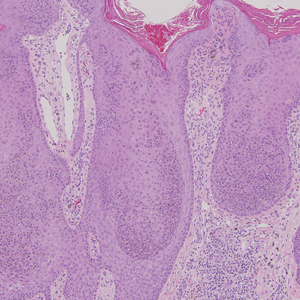

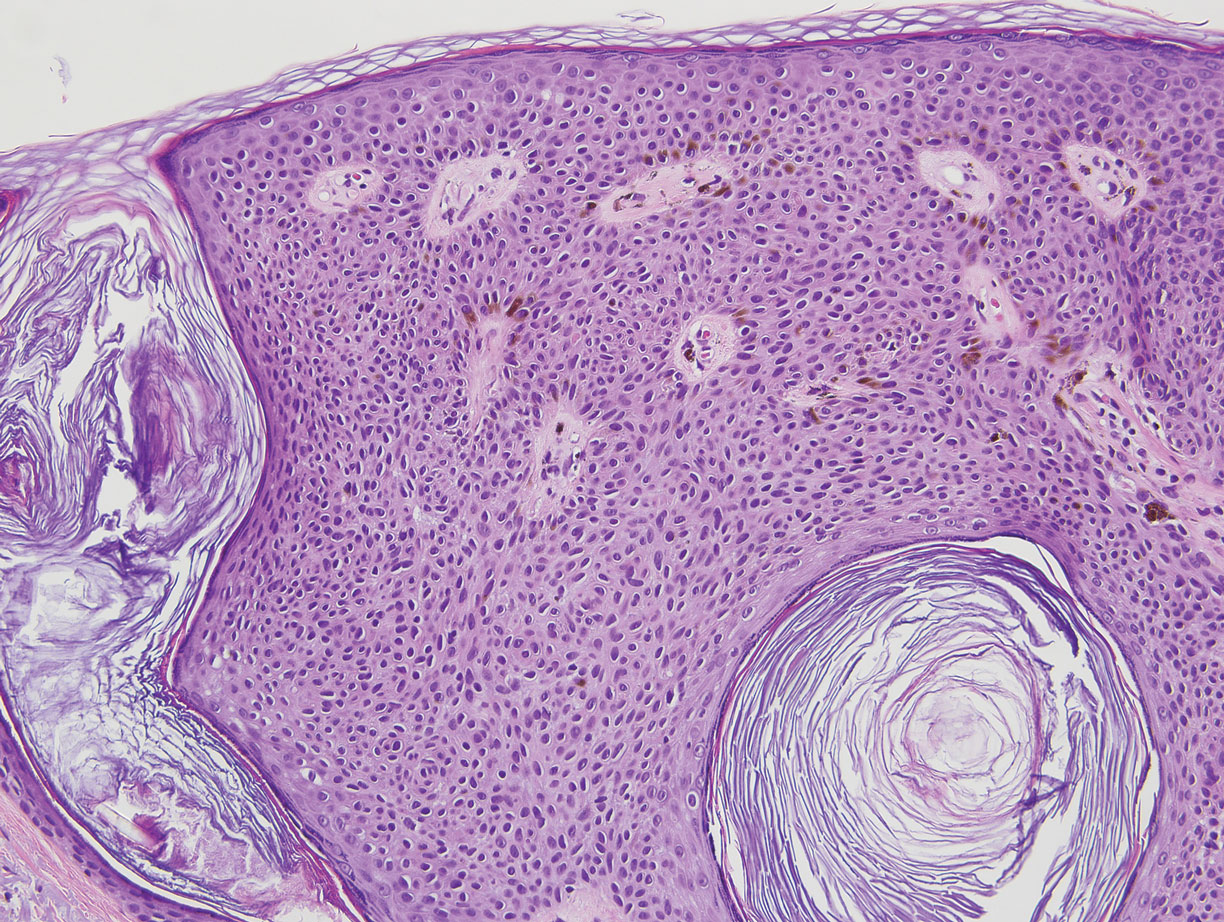

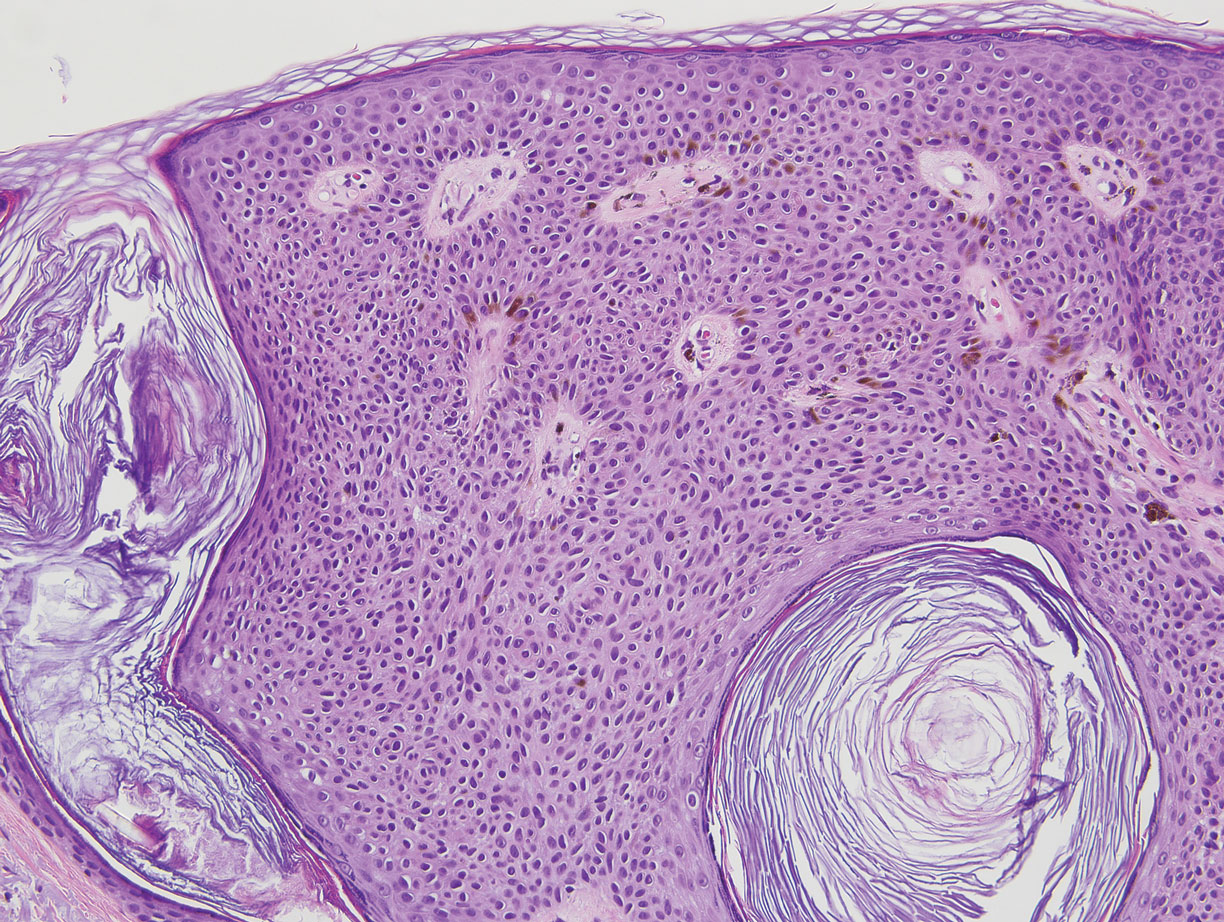

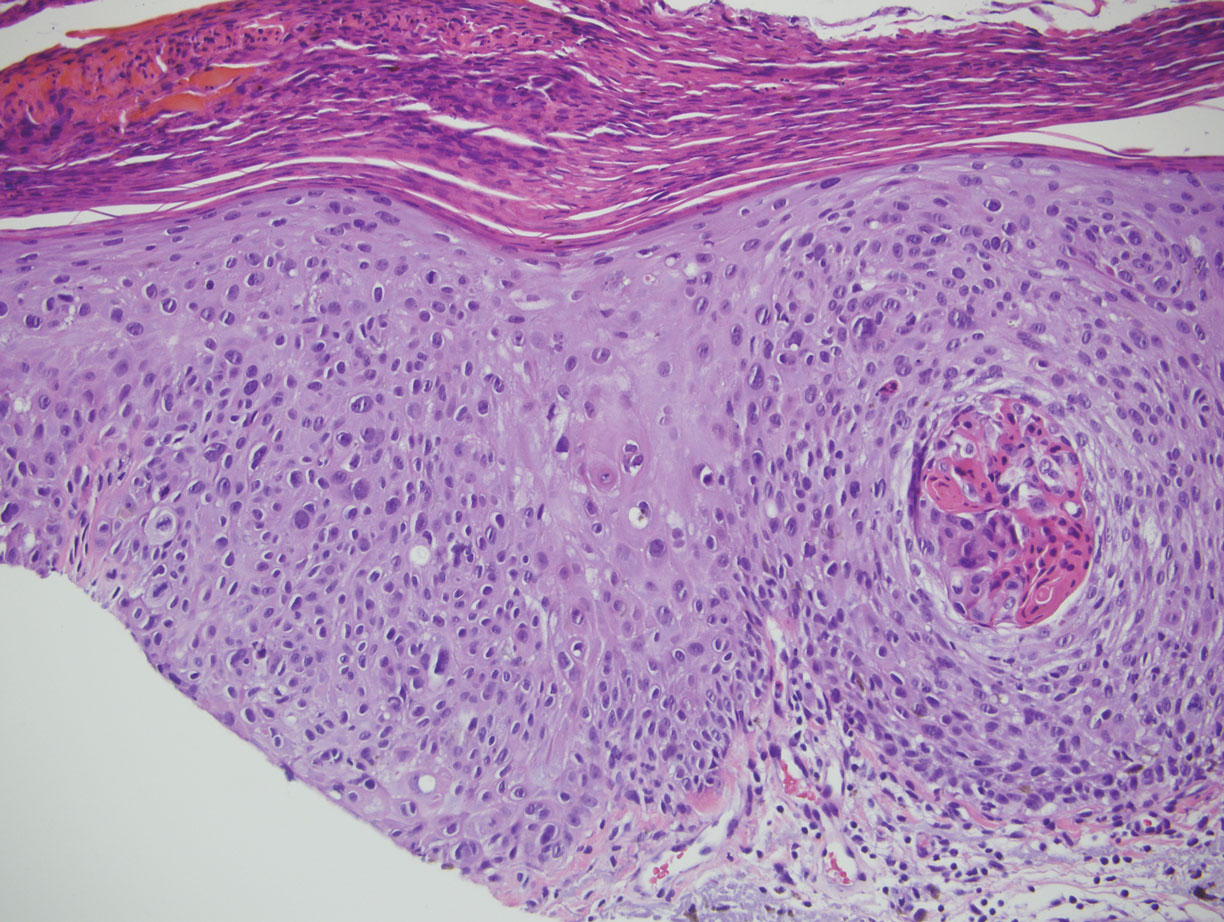

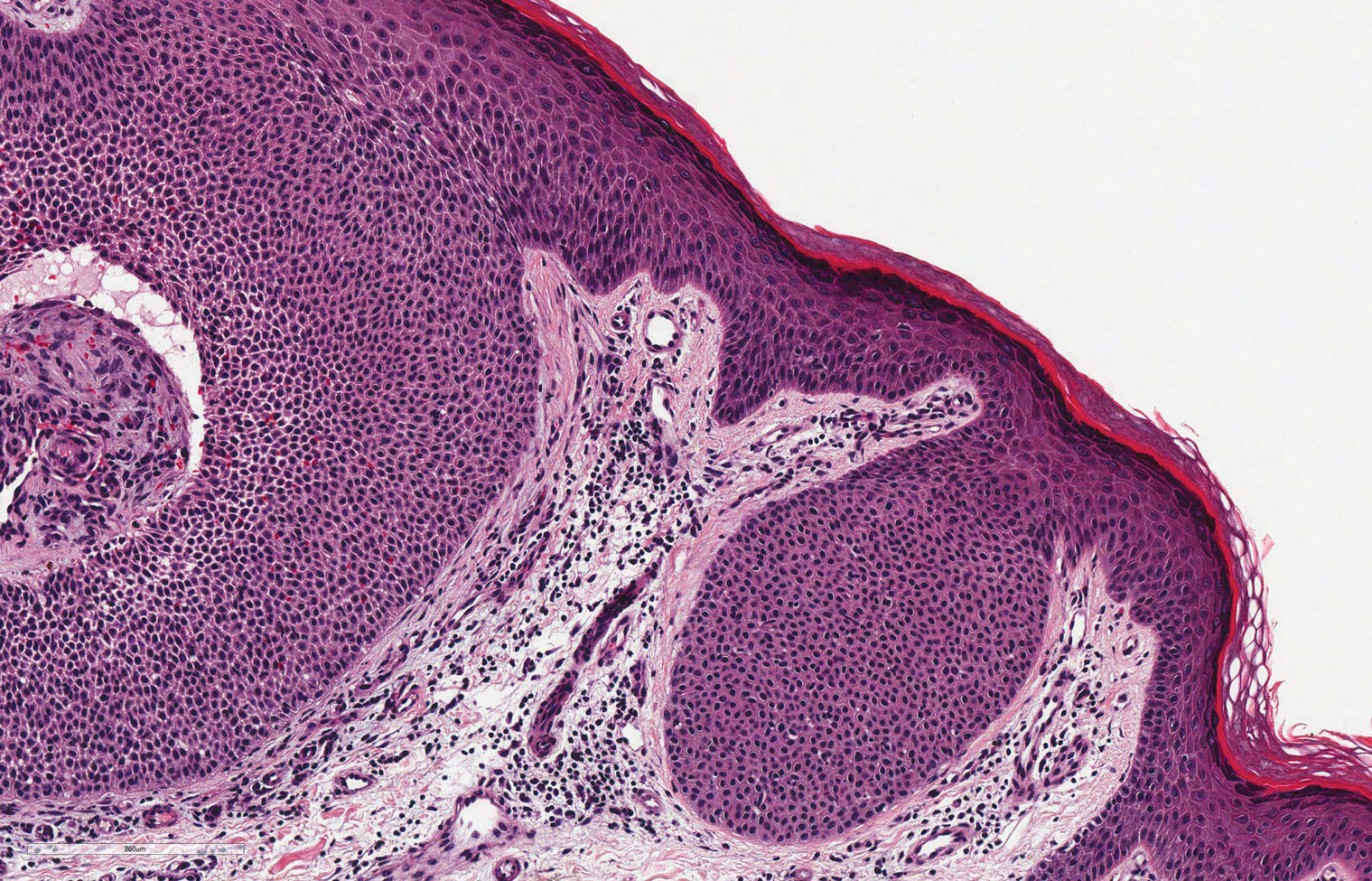

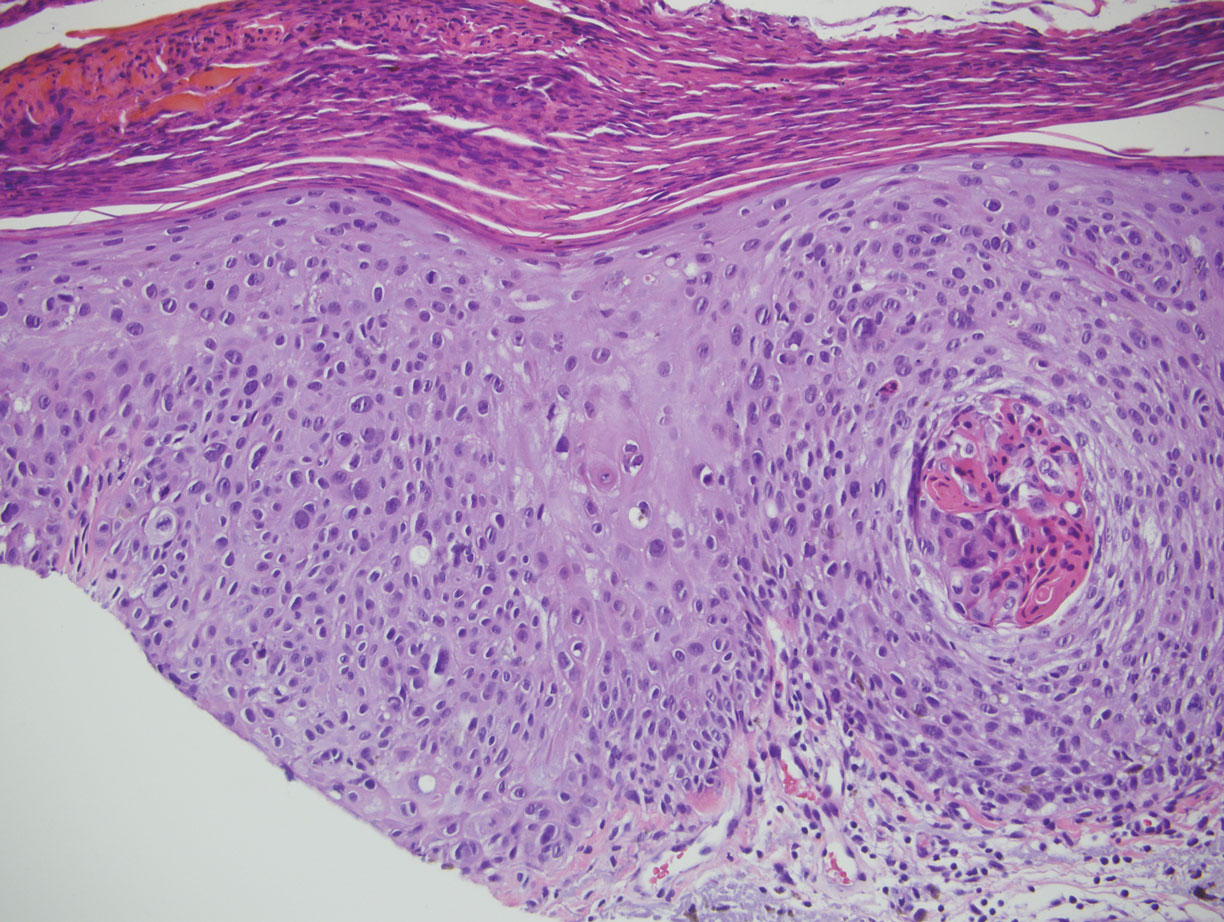

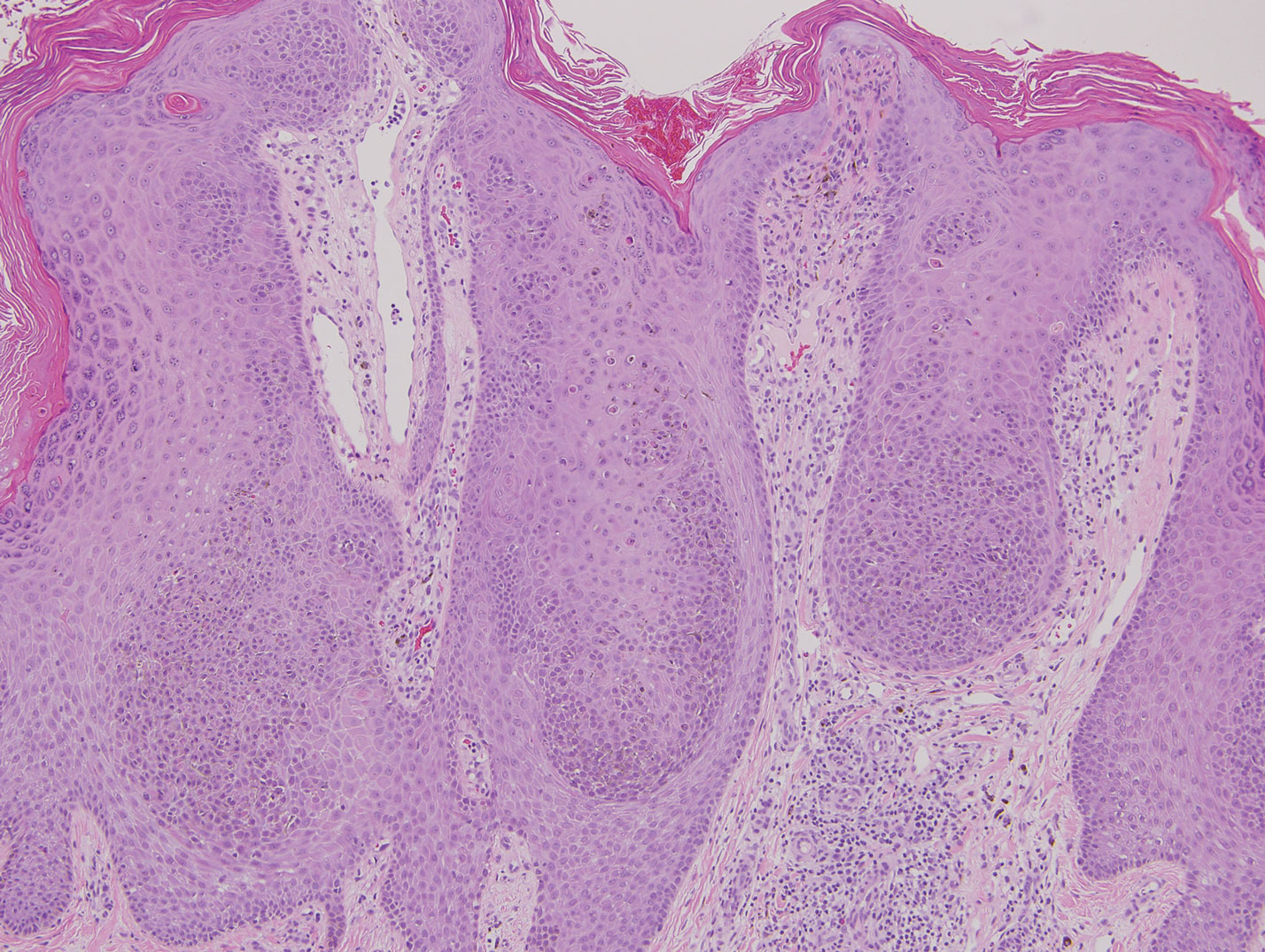

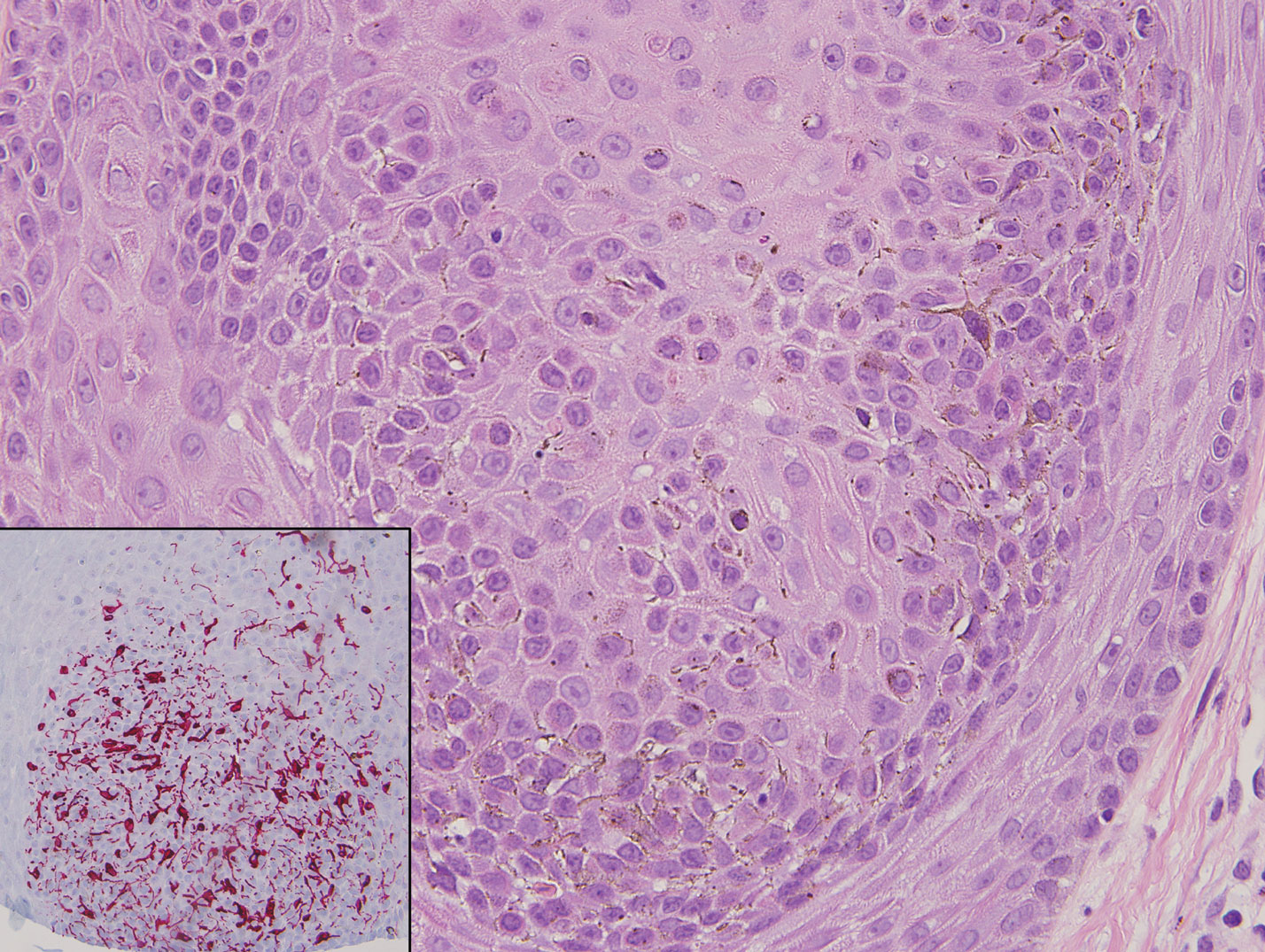

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

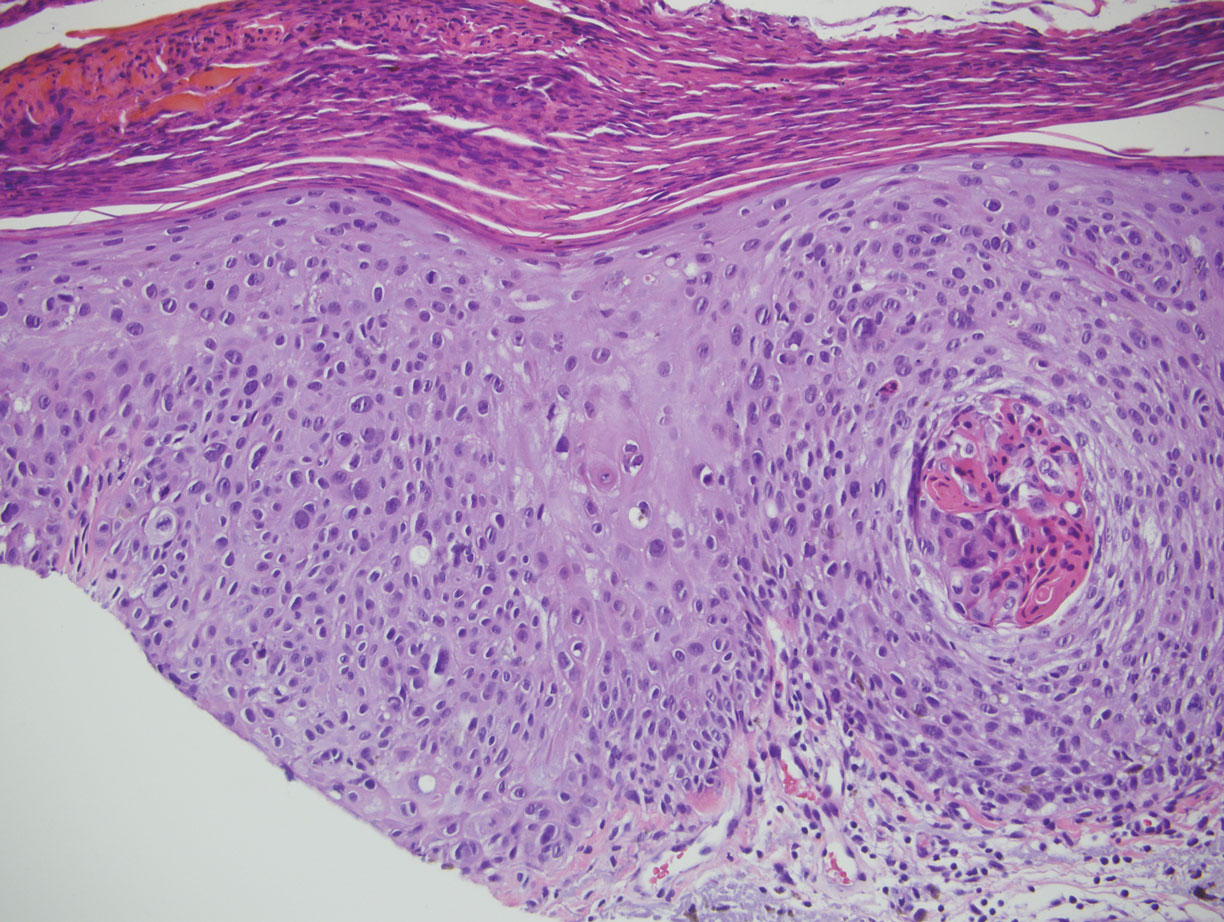

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

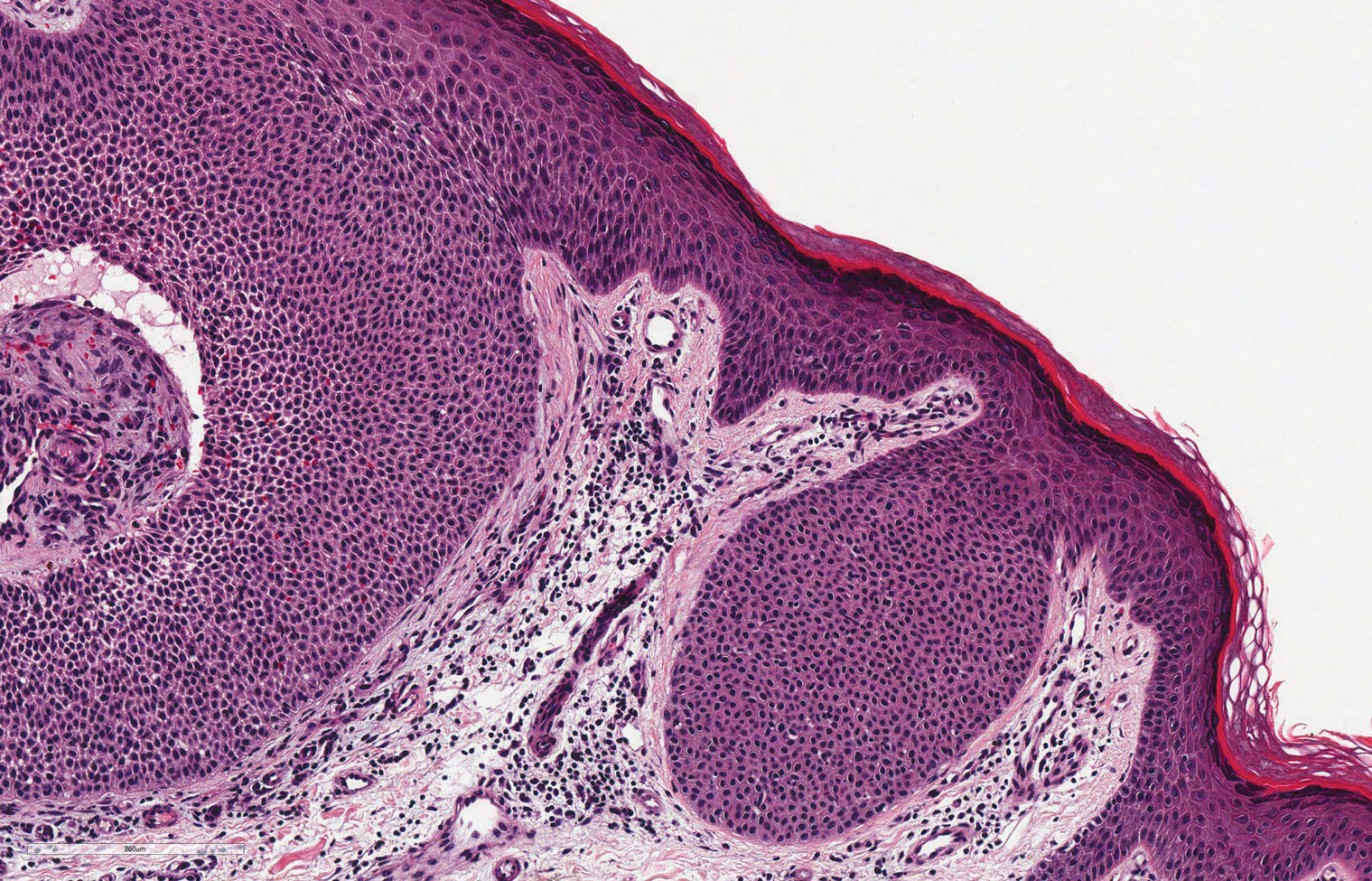

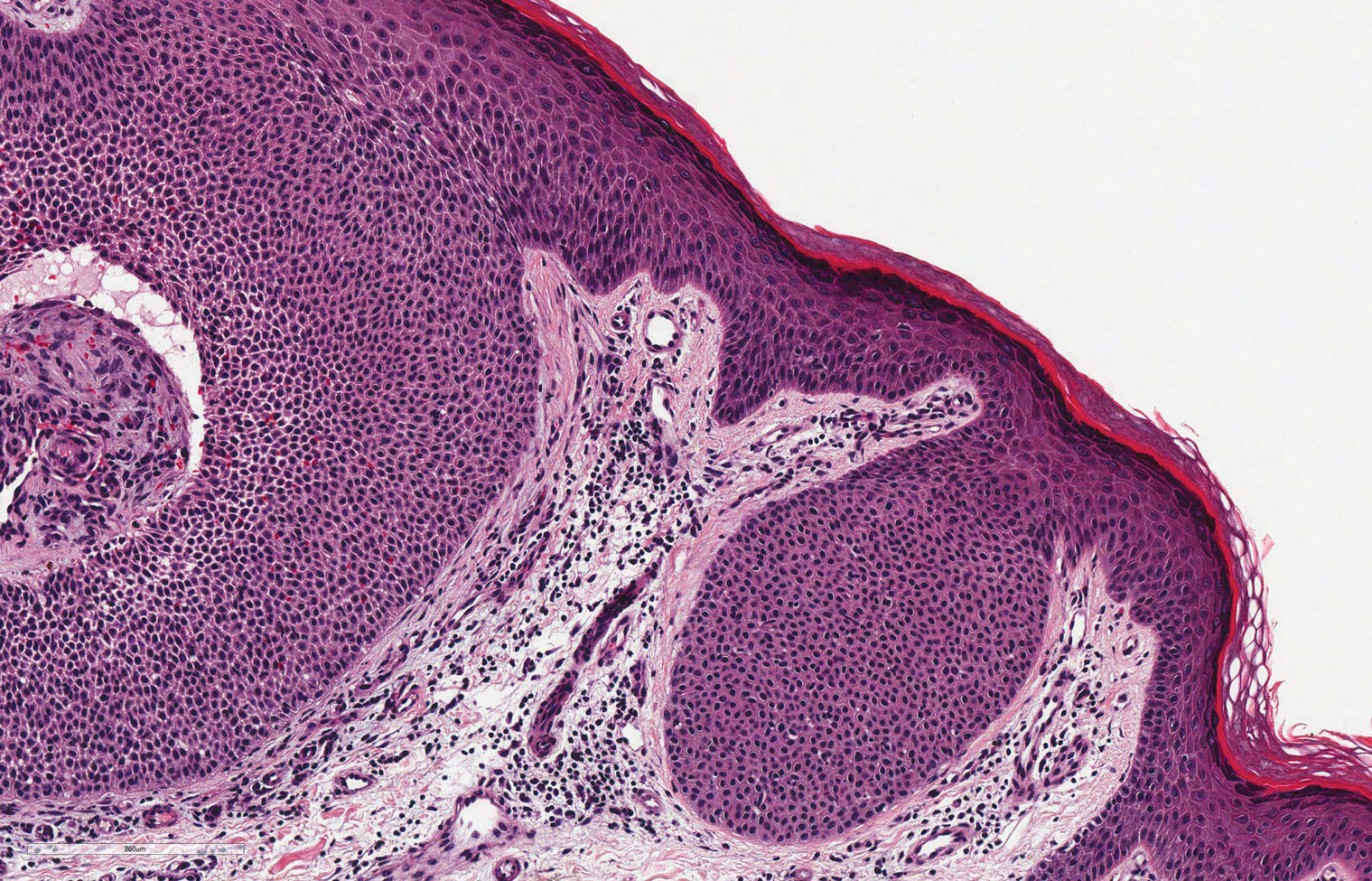

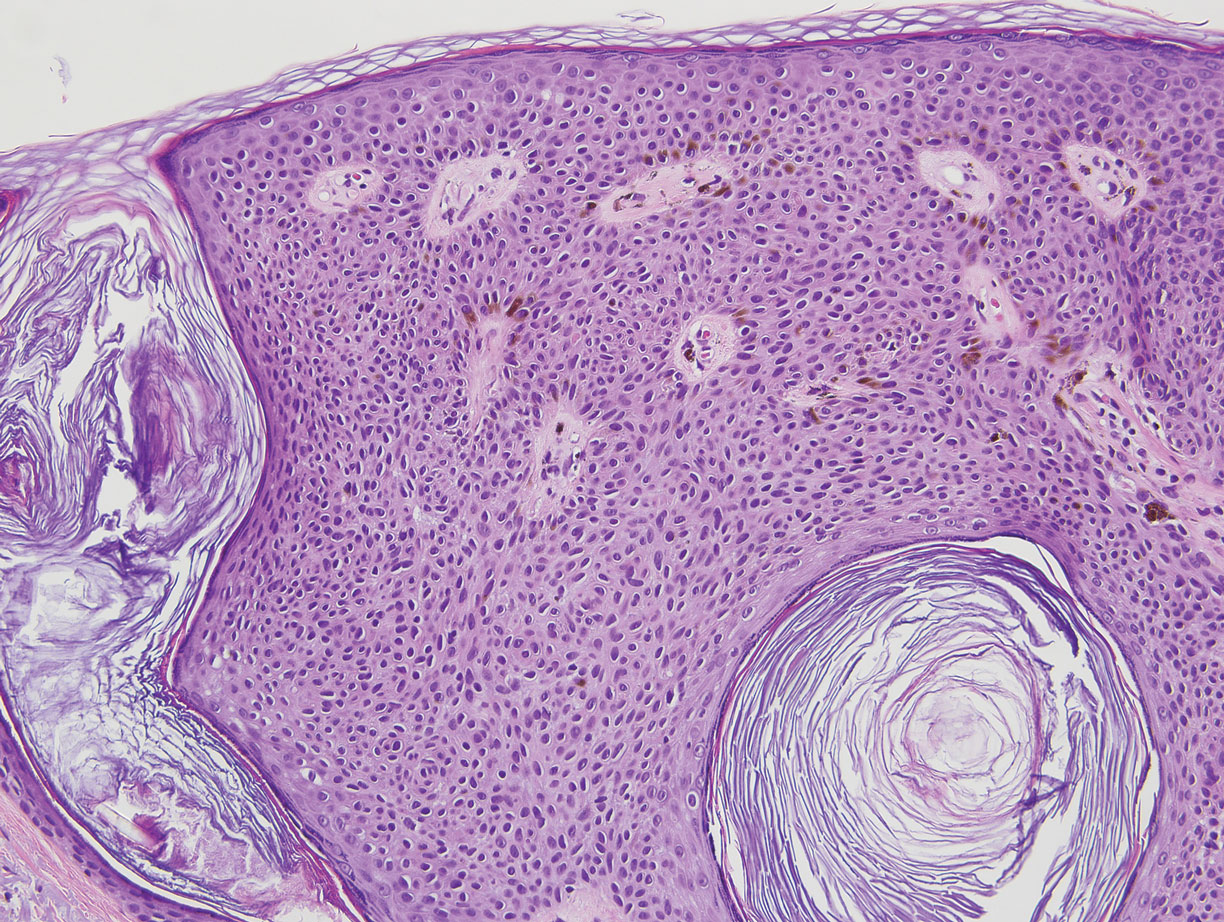

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Clonal Melanoacanthoma

Melanoacanthoma (MA) is an extremely rare, benign, epidermal tumor histologically characterized by keratinocytes and large, pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. These lesions are loosely related to seborrheic keratoses, and the term was first coined by Mishima and Pinkus1 in 1960. It is estimated that the lesion occurs in only 5 of 500,000 individuals and tends to occur in older, light-skinned individuals.2 The majority are slow growing and are present on the head, neck, or upper extremities; however, similar lesions also have been reported on the oral mucosa.3 Melanoacanthomas range in size from 2×2 to 15×15 cm; are clinically pigmented; and present as either a papule, plaque, nodule, or horn.2

Classic histologic findings of MA include papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperkeratosis with heavily pigmented dendritic melanocytes diffusely dispersed throughout all layers of the seborrheic keratosis-like epidermis.3 Other features include keratin-filled pseudocysts, Langerhans cells, reactive spindling of keratinocytes, and an inflammatory infiltrate. In our case, the classic histologic findings also were architecturally arranged in oval to round clones within the epidermis (quiz images 1 and 2). A MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells) immunostain was obtained that highlighted the numerous but benign-appearing, dendritic melanocytes (quiz image 2 [inset]). A dual MART-1/Ki67 immunostain later was obtained and demonstrated a negligible proliferation index within the dendritic melanocytes. Therefore, the diagnosis of clonal MA was rendered. This formation of epidermal clones also is called the Borst-Jadassohn phenomenon, which rarely occurs in MAs. This subtype is important to recognize because the clonal pattern can more closely mimic malignant neoplasms such as melanoma.

Hidroacanthoma simplex is an intraepidermal variant of eccrine poroma. It is a rare entity that typically occurs in the extremities of women as a hyperkeratotic plaque. These typically clonal epidermal tumors may be heavily pigmented and rarely contain dendritic melanocytes; therefore, they may be confused with MA. However, classic histology will reveal an intraepidermal clonal proliferation of bland, monotonous, cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm, as well as occasional cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).4 These ducts will highlight with carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunostaining.

Malignant melanoma typically presents as a growing pigmented lesion and therefore can clinically mimic MA. Histologically, MA could be confused with melanoma due to the increased number of melanocytes plus the appearance of pagetoid spread resulting from the diffuse presence of melanocytes throughout the neoplasm. However, histologic assessment of melanoma should reveal cytologic atypia such as nuclear enlargement, hyperchromasia, molding, pleomorphism, and mitotic activity (Figure 2). Architectural atypia such as poor lateral circumscription of melanocytes, confluence and pagetoid spread of nondendritic atypical junctional melanocytes, production of pigment in deep dermal nests of melanocytes, and lack of maturation and dispersion of dermal melanocytes also should be seen.5 Unlike a melanocytic neoplasm, true melanocytic nests are not seen in MA, and the melanocytes are bland, normal-appearing but heavily pigmented, dendritic melanocytes. Electron microscopy has shown a defect in the transfer of melanin from these highly dendritic melanocytes to the keratinocytes.6

Similar to melanoma, seborrheic keratosis presents as a pigmented growing lesion; therefore, definitive diagnosis often is achieved via skin biopsy. Classic histologic findings include acanthotic or exophytic epidermal growth with a dome-shaped configuration containing multiple cornified hornlike cysts (Figure 3).7 Multiple keratin plugs and variably sized concentric keratin islands are common features. There may be varying degrees of melanin pigment deposition among the proliferating cells, and clonal formation may occur. Melanocyte-specific special stains and immunostains can be used to differentiate MA from seborrheic keratosis by highlighting numerous dendritic melanocytes diffusely spread throughout the epidermis in MA vs a normal distribution of occasional junctional melanocytes in seborrheic keratosis.2,8

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ presents histologically with cytologically atypical keratinocytes encompassing the full thickness of the epidermis and sometimes crushing the basement membrane zone (Figure 4). There is a loss of the granular layer and overlying parakeratosis that often spares the adnexal ostial epithelium.9 Clonal formation can occur as well as increased pigment production. In comparison, bland keratinocytes are seen in MA.

Establishing the diagnosis of MA based on clinical features alone can be difficult. Dermoscopy can prove to be useful and typically will show a sunburst pattern with ridges and fissures.2 However, seborrheic keratoses and melanomas can have similar dermoscopic findings10; therefore, a biopsy often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

- Mishima Y, Pinkus H. Benign mixed tumor of melanocytes and malpighian cells: melanoacanthoma: its relationship to Bloch's benign non-nevoid melanoepithelioma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:539-550.

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C P, Calame A, et al. Melanoacanthoma masquerading as melanoma: case reports and literature review. Cureus. 2019;11:E4998.

- Fornatora ML, Reich RF, Haber S, et al. Oral melanoacanthoma: a report of 10 cases, review of literature, and immunohistochemical analysis for HMB-45 reactivity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:12-15.

- Rahbari H. Hidroacanthoma simplex--a review of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:219-225.

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:S34-S40.

- Mishra DK, Jakati S, Dave TV, et al. A rare pigmented lesion of the eyelid. Int J Trichol. 2019;11:167-169.

- Greco MJ, Mahabadi N, Gossman W. Seborrheic keratosis. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545285/. Accessed September 18, 2020.

- Kihiczak G, Centurion SA, Schwartz RA, et al. Giant cutaneous melanoacanthoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:936-937.

- Morais P, Schettini A, Junior R. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma: a case report and importance of differential diagnosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:96-98.

- Chung E, Marqhoob A, Carrera C, et al. Clinical and dermoscopic features of cutaneous melanoacanthoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1129-1130.

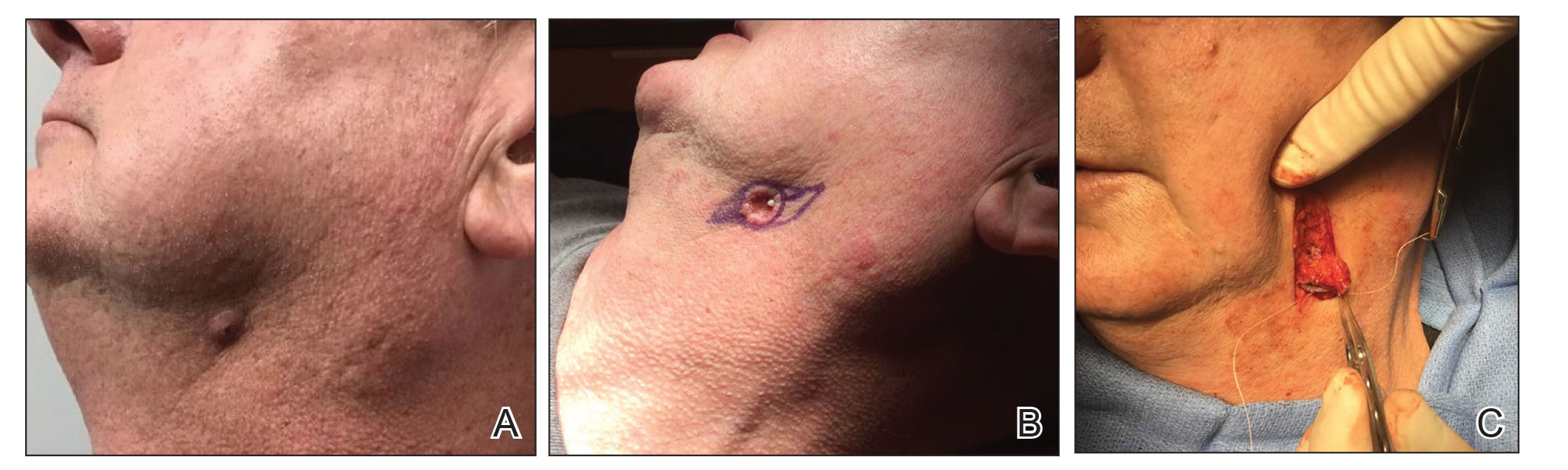

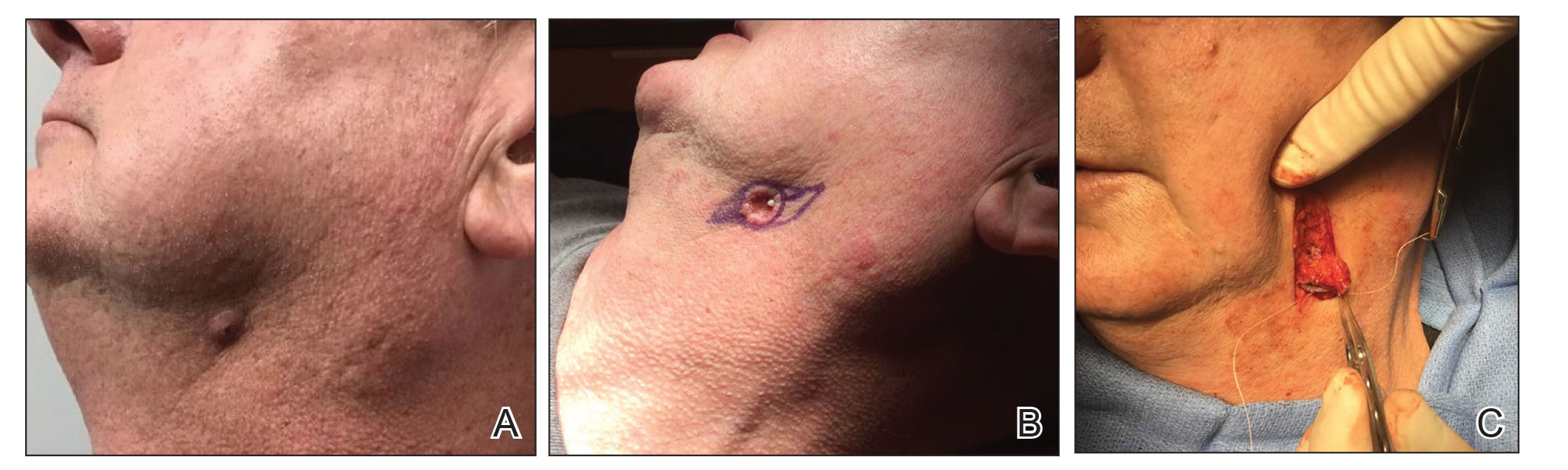

A 49-year-old man with light brown skin and no history of skin cancer presented with a pruritic lesion on the scalp of 3 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 7×3-cm, brown, mammillated plaque on the left parietal scalp. A shave biopsy of the scalp lesion was performed.

Influenza Vaccination Recommendations During Use of Select Immunosuppressants for Psoriasis

A 42-year-old woman with psoriasis presents for a checkup at the dermatology clinic. Her psoriasis has been fairly stable on methotrexate with no recent flares. She presents her concern of the coronavirus pandemic continuing into the flu season and mentions she would like to minimize her chances of having a respiratory illness. The influenza vaccine has just become available, and she inquires when she can get the vaccine and whether it will interfere with her treatment. What are your recommendations for the patient?

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated, inflammatory skin condition stemming from hyperproliferation of keratinocytes that classically involves erythematous skin plaques with overlying scale. Treatment options vary widely and include topical modalities, phototherapy, immunosuppressants, and biologic agents. Selection of treatment largely depends on the severity and extent of body surface area involvement; systemic therapy generally is indicated when the affected body surface area is greater than 5% to 10%. In patients on systemic therapy, increased susceptibility to infection is a priority concern for prescribing physicians. In the context of continuing immunosuppressive medications, vaccines that reduce susceptibility to infectious diseases can play an important role in reducing morbidity and mortality for these patients; however, an important consideration is that in patients with chronic conditions and frequent hospital visits, vaccines may be administered by various clinicians who may not be familiar with the management of immunosuppressive treatments. It is pivotal for prescribing dermatologists to provide appropriate vaccination instructions for the patient and any future clinicians to ensure vaccine efficacy in these patients.

The intramuscular influenza vaccine is a killed vaccine that is administered annually and has been shown to be safe for use in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients.1,2 Despite its safety, questions remain regarding the efficacy of vaccines while a patient is unable to mount a normal immune response and whether the treatment must be altered to maximize immunogenicity. The common systemic treatment options for psoriasis and any recommendations that can be made regarding administration of the influenza vaccine in that context are outlined in the Table. Given the sparsity of clinical data measuring vaccine immunogenicity in patients with psoriasis, vaccine guidelines are drawn from patients with various conditions who are receiving the same dose of medication as indicated for psoriasis.

Immunosuppressants and biologics commonly are used in dermatology for the management of many conditions, including psoriasis. As flu season approaches in the setting of a global pandemic, it is critical to understand the effects of commonly used psoriasis medications on the influenza vaccine. Through a brief review of the latest data concerning their interactions, dermatologists will be able to provide appropriate recommendations that maximize a patient’s immune response to the vaccine while minimizing adverse effects from holding medication.

- Zbinden D, Manuel O. Influenza vaccination in immunocompromised patients: efficacy and safety. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:131-139.

- Milanovic M, Stojanovich L, Djokovic A, et al. Influenza vaccination in autoimmune rheumatic disease patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:29-34.

- Dengler TJ, Strnad N, Bühring I, et al. Differential immune response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in immunosuppressed patients after heart transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66:1340-1347.

- Willcocks LC, Chaudhry AN, Smith JC, et al. The effect of sirolimus therapy on vaccine responses in transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2006-2011.

- Chioato A, Noseda E, Stevens M, et al. Treatment with the interleukin-17A-blocking antibody secukinumab does not interfere with the efficacy of influenza and meningococcal vaccinations in healthy subjects: results of an open-label, parallel-group, randomized single-center study. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:1597-1602.

- Richi P, Martín MD, de Ory F, et al. Secukinumab does not impair the immunogenic response to the influenza vaccine in patients. RMD Open. 2019;5:e001018.

- Furer V, Zisman D, Kaufman I, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of vaccination against seasonal influenza vaccine in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with secukinumab. Vaccine. 2020;38:847-851.

- Hua C, Barnetche T, Combe B, et al. Effect of methotrexate, anti-tumor necrosis factor α, and rituximab on the immune response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1016-1026.

- Park JK, Choi Y, Winthrop KL, et al. Optimal time between the last methotrexate administration and seasonal influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis: post hoc analysis of a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1283-1284.

- Park JK, Lee MA, Lee EY, et al. Effect of methotrexate discontinuation on efficacy of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1559-1565.

- Park JK, Lee YJ, Shin K, et al. Impact of temporary methotrexate discontinuation for 2 weeks on immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:898-904.

- Shirai S, Hara M, Sakata Y, et al. Immunogenicity of quadrivalent influenza vaccine for patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1082-1091.

- Fomin I. Vaccination against influenza in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease modifying drugs, including TNF blockers. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:191-194.

- Bosaeed M, Kumar D. Seasonal influenza vaccine in immunocompromised persons. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:1311-1322.

- Kaine JL, Kivitz AJ, Birbara C, et al. Immune responses following administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines to patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:272-279.

A 42-year-old woman with psoriasis presents for a checkup at the dermatology clinic. Her psoriasis has been fairly stable on methotrexate with no recent flares. She presents her concern of the coronavirus pandemic continuing into the flu season and mentions she would like to minimize her chances of having a respiratory illness. The influenza vaccine has just become available, and she inquires when she can get the vaccine and whether it will interfere with her treatment. What are your recommendations for the patient?

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated, inflammatory skin condition stemming from hyperproliferation of keratinocytes that classically involves erythematous skin plaques with overlying scale. Treatment options vary widely and include topical modalities, phototherapy, immunosuppressants, and biologic agents. Selection of treatment largely depends on the severity and extent of body surface area involvement; systemic therapy generally is indicated when the affected body surface area is greater than 5% to 10%. In patients on systemic therapy, increased susceptibility to infection is a priority concern for prescribing physicians. In the context of continuing immunosuppressive medications, vaccines that reduce susceptibility to infectious diseases can play an important role in reducing morbidity and mortality for these patients; however, an important consideration is that in patients with chronic conditions and frequent hospital visits, vaccines may be administered by various clinicians who may not be familiar with the management of immunosuppressive treatments. It is pivotal for prescribing dermatologists to provide appropriate vaccination instructions for the patient and any future clinicians to ensure vaccine efficacy in these patients.

The intramuscular influenza vaccine is a killed vaccine that is administered annually and has been shown to be safe for use in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients.1,2 Despite its safety, questions remain regarding the efficacy of vaccines while a patient is unable to mount a normal immune response and whether the treatment must be altered to maximize immunogenicity. The common systemic treatment options for psoriasis and any recommendations that can be made regarding administration of the influenza vaccine in that context are outlined in the Table. Given the sparsity of clinical data measuring vaccine immunogenicity in patients with psoriasis, vaccine guidelines are drawn from patients with various conditions who are receiving the same dose of medication as indicated for psoriasis.

Immunosuppressants and biologics commonly are used in dermatology for the management of many conditions, including psoriasis. As flu season approaches in the setting of a global pandemic, it is critical to understand the effects of commonly used psoriasis medications on the influenza vaccine. Through a brief review of the latest data concerning their interactions, dermatologists will be able to provide appropriate recommendations that maximize a patient’s immune response to the vaccine while minimizing adverse effects from holding medication.

A 42-year-old woman with psoriasis presents for a checkup at the dermatology clinic. Her psoriasis has been fairly stable on methotrexate with no recent flares. She presents her concern of the coronavirus pandemic continuing into the flu season and mentions she would like to minimize her chances of having a respiratory illness. The influenza vaccine has just become available, and she inquires when she can get the vaccine and whether it will interfere with her treatment. What are your recommendations for the patient?

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated, inflammatory skin condition stemming from hyperproliferation of keratinocytes that classically involves erythematous skin plaques with overlying scale. Treatment options vary widely and include topical modalities, phototherapy, immunosuppressants, and biologic agents. Selection of treatment largely depends on the severity and extent of body surface area involvement; systemic therapy generally is indicated when the affected body surface area is greater than 5% to 10%. In patients on systemic therapy, increased susceptibility to infection is a priority concern for prescribing physicians. In the context of continuing immunosuppressive medications, vaccines that reduce susceptibility to infectious diseases can play an important role in reducing morbidity and mortality for these patients; however, an important consideration is that in patients with chronic conditions and frequent hospital visits, vaccines may be administered by various clinicians who may not be familiar with the management of immunosuppressive treatments. It is pivotal for prescribing dermatologists to provide appropriate vaccination instructions for the patient and any future clinicians to ensure vaccine efficacy in these patients.

The intramuscular influenza vaccine is a killed vaccine that is administered annually and has been shown to be safe for use in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients.1,2 Despite its safety, questions remain regarding the efficacy of vaccines while a patient is unable to mount a normal immune response and whether the treatment must be altered to maximize immunogenicity. The common systemic treatment options for psoriasis and any recommendations that can be made regarding administration of the influenza vaccine in that context are outlined in the Table. Given the sparsity of clinical data measuring vaccine immunogenicity in patients with psoriasis, vaccine guidelines are drawn from patients with various conditions who are receiving the same dose of medication as indicated for psoriasis.

Immunosuppressants and biologics commonly are used in dermatology for the management of many conditions, including psoriasis. As flu season approaches in the setting of a global pandemic, it is critical to understand the effects of commonly used psoriasis medications on the influenza vaccine. Through a brief review of the latest data concerning their interactions, dermatologists will be able to provide appropriate recommendations that maximize a patient’s immune response to the vaccine while minimizing adverse effects from holding medication.

- Zbinden D, Manuel O. Influenza vaccination in immunocompromised patients: efficacy and safety. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:131-139.

- Milanovic M, Stojanovich L, Djokovic A, et al. Influenza vaccination in autoimmune rheumatic disease patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:29-34.

- Dengler TJ, Strnad N, Bühring I, et al. Differential immune response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in immunosuppressed patients after heart transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66:1340-1347.

- Willcocks LC, Chaudhry AN, Smith JC, et al. The effect of sirolimus therapy on vaccine responses in transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2006-2011.

- Chioato A, Noseda E, Stevens M, et al. Treatment with the interleukin-17A-blocking antibody secukinumab does not interfere with the efficacy of influenza and meningococcal vaccinations in healthy subjects: results of an open-label, parallel-group, randomized single-center study. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:1597-1602.

- Richi P, Martín MD, de Ory F, et al. Secukinumab does not impair the immunogenic response to the influenza vaccine in patients. RMD Open. 2019;5:e001018.

- Furer V, Zisman D, Kaufman I, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of vaccination against seasonal influenza vaccine in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with secukinumab. Vaccine. 2020;38:847-851.

- Hua C, Barnetche T, Combe B, et al. Effect of methotrexate, anti-tumor necrosis factor α, and rituximab on the immune response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1016-1026.

- Park JK, Choi Y, Winthrop KL, et al. Optimal time between the last methotrexate administration and seasonal influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis: post hoc analysis of a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1283-1284.

- Park JK, Lee MA, Lee EY, et al. Effect of methotrexate discontinuation on efficacy of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1559-1565.

- Park JK, Lee YJ, Shin K, et al. Impact of temporary methotrexate discontinuation for 2 weeks on immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:898-904.

- Shirai S, Hara M, Sakata Y, et al. Immunogenicity of quadrivalent influenza vaccine for patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1082-1091.

- Fomin I. Vaccination against influenza in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease modifying drugs, including TNF blockers. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:191-194.

- Bosaeed M, Kumar D. Seasonal influenza vaccine in immunocompromised persons. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:1311-1322.

- Kaine JL, Kivitz AJ, Birbara C, et al. Immune responses following administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines to patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:272-279.

- Zbinden D, Manuel O. Influenza vaccination in immunocompromised patients: efficacy and safety. Immunotherapy. 2014;6:131-139.

- Milanovic M, Stojanovich L, Djokovic A, et al. Influenza vaccination in autoimmune rheumatic disease patients. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2013;229:29-34.

- Dengler TJ, Strnad N, Bühring I, et al. Differential immune response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in immunosuppressed patients after heart transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66:1340-1347.

- Willcocks LC, Chaudhry AN, Smith JC, et al. The effect of sirolimus therapy on vaccine responses in transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2006-2011.

- Chioato A, Noseda E, Stevens M, et al. Treatment with the interleukin-17A-blocking antibody secukinumab does not interfere with the efficacy of influenza and meningococcal vaccinations in healthy subjects: results of an open-label, parallel-group, randomized single-center study. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:1597-1602.

- Richi P, Martín MD, de Ory F, et al. Secukinumab does not impair the immunogenic response to the influenza vaccine in patients. RMD Open. 2019;5:e001018.

- Furer V, Zisman D, Kaufman I, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of vaccination against seasonal influenza vaccine in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with secukinumab. Vaccine. 2020;38:847-851.

- Hua C, Barnetche T, Combe B, et al. Effect of methotrexate, anti-tumor necrosis factor α, and rituximab on the immune response to influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1016-1026.

- Park JK, Choi Y, Winthrop KL, et al. Optimal time between the last methotrexate administration and seasonal influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis: post hoc analysis of a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1283-1284.

- Park JK, Lee MA, Lee EY, et al. Effect of methotrexate discontinuation on efficacy of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1559-1565.

- Park JK, Lee YJ, Shin K, et al. Impact of temporary methotrexate discontinuation for 2 weeks on immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:898-904.

- Shirai S, Hara M, Sakata Y, et al. Immunogenicity of quadrivalent influenza vaccine for patients with inflammatory bowel disease undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1082-1091.

- Fomin I. Vaccination against influenza in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease modifying drugs, including TNF blockers. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:191-194.

- Bosaeed M, Kumar D. Seasonal influenza vaccine in immunocompromised persons. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:1311-1322.

- Kaine JL, Kivitz AJ, Birbara C, et al. Immune responses following administration of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines to patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:272-279.

Practice Points

- Patients receiving methotrexate appear to benefit from suspending treatment for 2 weeks following influenza vaccination, as it maximizes the seroprotective response.

- Patients receiving tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and low-dose IL-17 inhibitors have an unaltered humoral response to vaccination and attain protection equal to that of the general population.

- Patients treated with cyclosporine should be closely monitored for influenza symptoms even after vaccination, as approximately half of patients do not achieve a seroprotective response.

- Consider the increased risk for psoriatic flare during treatment suspension and the possibility of failed seroprotection, warranting close monitoring and clinical judgement tailored to each individual.

Tobacco-free homes yield more tobacco-free youth

Tsu-Suan Wu and Benjamin W. Chaffee, DDS, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, advised in their study in Pediatrics.

Previous studies have shown that children who grow up in a nonsmoking household are less likely to begin smoking themselves, and active parental engagement in interventions shows promise overall in protecting children from drug, alcohol, and illicit drug use. Households with rigid rules against smoking offer a deterrent for children who might otherwise be tempted, the researchers noted.

Other studies have shown that while youth smoking is on the decline, use of noncigarette products is increasing sharply. The inconspicuous appearance and attractive scents these delivery devices afford make it easier to conceal them from parents.

In the current study, using data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study involving 23,170 parents and youth ages 9 and up, Mr. Wu and Dr. Chaffee sought to assess to what extent parents had knowledge or suspicions of tobacco use and also to evaluate the association between youth initiating tobacco use and the establishment of household rules and engaging in regular conversation about tobacco.

Study results revealed in three of the four groups evaluated that youth were most likely to engage in using several different types of tobacco (polytobacco) products; in the fourth group, e-cigarette use was most common. Among polytobacco users, fully 77%-80% reported cigarette usage.

Parental knowledge and actions

Overall, Mr. Wu and Dr. Chaffee “identified substantial lapses in parents’ awareness of their children’s tobacco use.” Parents were most likely to register awareness when their children smoked cigarettes; half as many parents were aware or suspected use when noncigarette products were used.

Parents who had heightened awareness about possible tobacco usage tended to be the child’s mother, had completed lower levels of education, parented children who were older, male and non-Hispanic, and lived with a tobacco user.

Noteworthy was the growing percentage of parents who report awareness or suspicions of cigarette usage – approximately 70% – compared with previous study findings – about 40%. The researchers speculated that this increase could be directly tied to growing social concern regarding youth smoking. Unfortunately, parents will continue to be challenged to keep up with constantly changing e-cigarette designs in maintaining their awareness, Mr. Wu and Dr. Chaffee noted.

Establishing strict household rules was found to be more effective than just talking with youth about usage, which half of the youth reported their parents did. At all time points, the risk of tobacco initiation was 20%-26% lower for children who lived in a house with strict household rules forbidding any tobacco use by anyone. The researchers observed that success with the household rules method was best achieved with children at younger ages.

The study did not measure the quality or frequency of antitobacco conversations but it should not be concluded definitively that all parental communication is unhelpful, the researchers cautioned.

To their knowledge, this study is the first to analyze the effects of household antitobacco strategies on discouraging initiation the use of tobacco and other smoking products as well as assessing parental awareness surrounding tobacco usage among youth.

What to tell parents

In a separate interview, Kelly Curran, MD, MA, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, commented on the explosive growth of e-cigarette use in the last 7 years.

What makes e-cigs so difficult to detect is that they “can resemble common objects such as flash drives or pens, and as a result, can often be hidden or overlooked by parents,” noted Dr. Curran.

The most important message for parents from this study is that they have the potential to have a large impact in the prevention of tobacco initiation, she said. “This effort requires parents to ‘walk the walk’ instead of just ‘talking the talk.”

As the study revealed, simply talking to teens about not using tobacco products doesn’t decrease use, but “creating strict household rules around no tobacco use for all visitors and inhabitants has a significant impact in decreasing youth tobacco initiation – by nearly 25%,” she added. “When counseling patients and families about tobacco prevention, clinicians should encourage them to create a tobacco-free home.”

The study was funded by a National Institutes of Health grant and the Delta Dental Community Care Foundation. The authors have no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Curran, who is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board, said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Wu T-S and Chaffee BW. Pediatrics 2020 October. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4034.

Tsu-Suan Wu and Benjamin W. Chaffee, DDS, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, advised in their study in Pediatrics.

Previous studies have shown that children who grow up in a nonsmoking household are less likely to begin smoking themselves, and active parental engagement in interventions shows promise overall in protecting children from drug, alcohol, and illicit drug use. Households with rigid rules against smoking offer a deterrent for children who might otherwise be tempted, the researchers noted.

Other studies have shown that while youth smoking is on the decline, use of noncigarette products is increasing sharply. The inconspicuous appearance and attractive scents these delivery devices afford make it easier to conceal them from parents.

In the current study, using data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study involving 23,170 parents and youth ages 9 and up, Mr. Wu and Dr. Chaffee sought to assess to what extent parents had knowledge or suspicions of tobacco use and also to evaluate the association between youth initiating tobacco use and the establishment of household rules and engaging in regular conversation about tobacco.

Study results revealed in three of the four groups evaluated that youth were most likely to engage in using several different types of tobacco (polytobacco) products; in the fourth group, e-cigarette use was most common. Among polytobacco users, fully 77%-80% reported cigarette usage.

Parental knowledge and actions

Overall, Mr. Wu and Dr. Chaffee “identified substantial lapses in parents’ awareness of their children’s tobacco use.” Parents were most likely to register awareness when their children smoked cigarettes; half as many parents were aware or suspected use when noncigarette products were used.

Parents who had heightened awareness about possible tobacco usage tended to be the child’s mother, had completed lower levels of education, parented children who were older, male and non-Hispanic, and lived with a tobacco user.

Noteworthy was the growing percentage of parents who report awareness or suspicions of cigarette usage – approximately 70% – compared with previous study findings – about 40%. The researchers speculated that this increase could be directly tied to growing social concern regarding youth smoking. Unfortunately, parents will continue to be challenged to keep up with constantly changing e-cigarette designs in maintaining their awareness, Mr. Wu and Dr. Chaffee noted.

Establishing strict household rules was found to be more effective than just talking with youth about usage, which half of the youth reported their parents did. At all time points, the risk of tobacco initiation was 20%-26% lower for children who lived in a house with strict household rules forbidding any tobacco use by anyone. The researchers observed that success with the household rules method was best achieved with children at younger ages.

The study did not measure the quality or frequency of antitobacco conversations but it should not be concluded definitively that all parental communication is unhelpful, the researchers cautioned.

To their knowledge, this study is the first to analyze the effects of household antitobacco strategies on discouraging initiation the use of tobacco and other smoking products as well as assessing parental awareness surrounding tobacco usage among youth.

What to tell parents

In a separate interview, Kelly Curran, MD, MA, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City, commented on the explosive growth of e-cigarette use in the last 7 years.