User login

New-Onset Pemphigoid Gestationis Following COVID-19 Vaccination

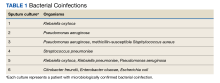

To the Editor:

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG), or gestational pemphigoid, is a rare autoimmune bullous disease (AIBD) occurring in 1 in 50,000 pregnancies. It is characterized by abrupt development of intensely pruritic papules and urticarial plaques, followed by an eruption of blisters.1 We present a case of new-onset PG that erupted 10 days following SARs-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech).

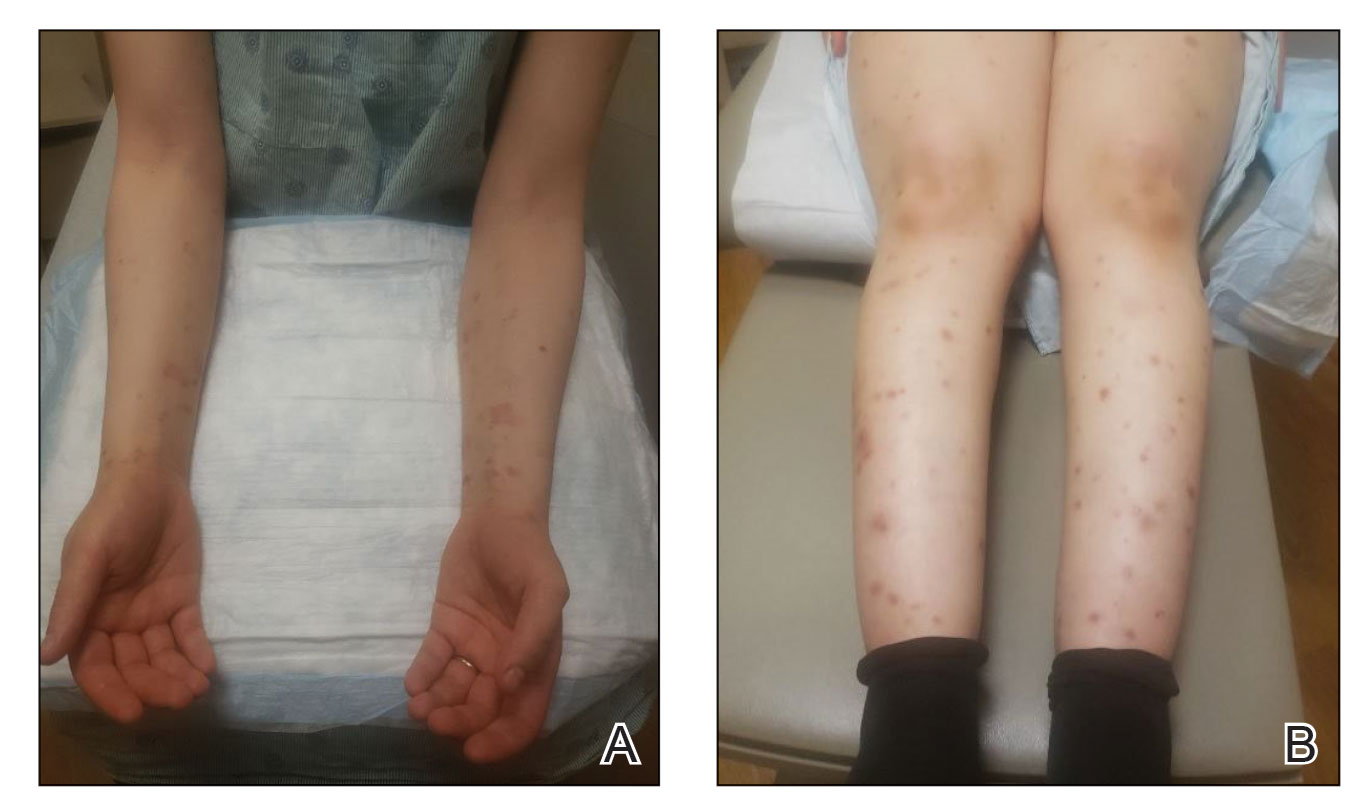

A 36-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 1, para 0, aborta 0) at 37 weeks’ gestation presented to our AIBD clinic with a pruritic dermatitis of 6 weeks’ duration that developed 10 days after receiving the second dose of BNT162b2. Multiple intensely pruritic, red bumps presented first on the forearms and within days spread to the thighs, hands, and abdomen, followed by progression to the ankles, feet, and back 2 weeks later. An initial biopsy was consistent with subacute spongiotic dermatitis with rare eosinophils. She found minimal relief from diphenhydramine or topical steroids. She denied oral, nasal, ocular, or genital involvement or history of any other skin disease. The pregnancy had been otherwise uneventful.

Physical examination revealed annular edematous plaques on the trunk and buttocks; excoriated and erythematous papules on the neck, trunk, arms, and legs; and scattered vesicles along the fingers, arms, hands, abdomen, back, legs, and feet (Figure 1). The Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) total skin activity score was 25.3, corresponding to moderate disease activity (validated at 20–56).2 The BPDAI total pruritus component score was 20. A repeat biopsy for direct immunofluorescence showed faint linear deposits of IgG and bright linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of IgG localized to the blister roof of salt-split skin at a dilution of 1:40. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-BP180 was 62 U/mL (negative, <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL), and anti-BP230 autoantibodies were less than 9 U/mL (negative <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL). Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, PG was diagnosed.

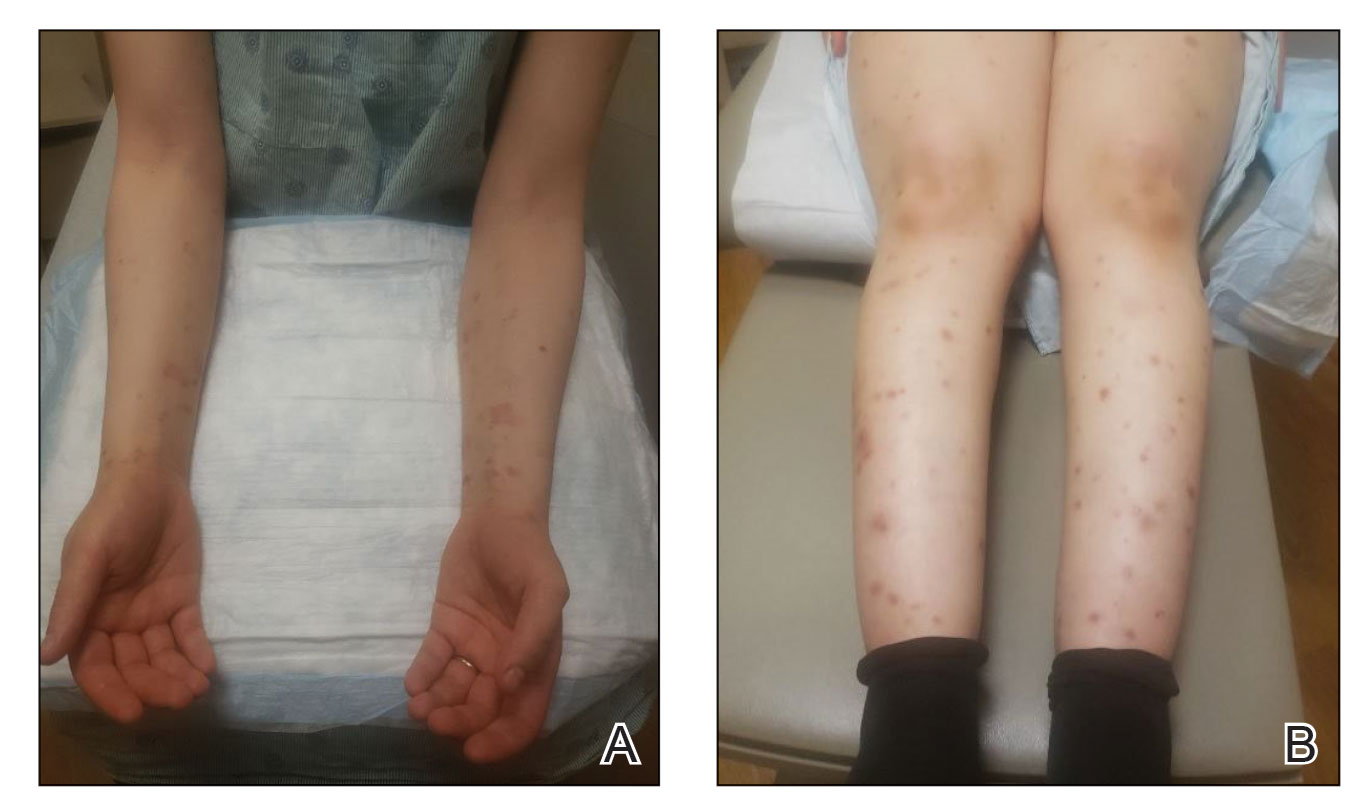

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and antihistamines while continuing topical steroids. Pruritus and blistering improved close to delivery. Fetal monitoring with regular biophysical profiles remained normal. The patient delivered a healthy neonate without skin lesions at 40 weeks’ gestation. The disease flared 2 days after delivery, and prednisone was increased to 40 mg and slowly tapered. Two months after delivery, the patient remained on prednisone 10 mg daily with ongoing but reduced blistering and pruritus (Figure 2). The BPDAI total skin activity and pruritus component scores remained elevated at 20.3 and 14, respectively, and anti-BP180 was 44 U/mL. After a discussion with the patient on safe systemic therapy while breastfeeding, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was initiated. The patient received 3 monthly infusions at 2 g/kg and was able to taper the prednisone to 5 mg every other day without new lesions. Four months after completion of IVIG therapy, she achieved complete remission off all therapy.

Management of PG begins with topical corticosteroids, but most patients require systemic steroid therapy.1 Remission commonly occurs close to delivery, and 75% of patients flare post partum, though the disease typically resolves 6 months following delivery.1,3,4 For persistent intrapartum cases requiring more than prednisone 20 mg daily, therapy can include dapsone, IVIG, azathioprine, rituximab, or plasmapheresis.4,5 Dapsone and IVIG are compatible with breastfeeding postpartum, but if dapsone is selected, the infant must be monitored for hemolytic anemia.5 Pemphigoid gestationis increases the risk for a premature or small-for-gestational-age neonate, necessitating regular fetal monitoring until delivery.1 Cutaneous lesions may affect the newborn, though this occurrence is rare and self-limiting.6Pemphigoid gestationis may recur in subsequent pregnancies at a rate of 33% to 55%, with earlier and more severe presentations.4

Clinically and histologically, PG closely resembles bullous pemphigoid (BP), but the exact pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recently, another case of what was termed pseudo-PG has been described 3 days following administration of the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.7 Since the introduction of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, cases of postvaccination BP, BP-like eruptions, and pemphigus vulgaris have been described.8-11 Tomayko et al10 reported 12 cases of subepidermal eruptions, including BP, in which 7 patients developed blisters after the second dose of either the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccine. Three patients who developed BP after the first dose of the vaccine and chose to receive the second dose tolerated it well, with a mild flare observed in 1 patient.10 Similarly, subsequent vaccine doses in reports of vaccine-associated AIBD resulted in increased disease activity in 21% of cases.12 COVID-19 vaccine–associated BP, similar to drug-induced BP, seemingly displays a milder course of disease compared to the classic form of BP.10,13 More follow-up is needed to better understand these reactions and inform appropriate discussions on the administration of booster doses. Currently, completion of the vaccination series against COVID-19 is advisable given the paucity of reports of postvaccination AIBD and the risk for COVID-19 infection, but careful discussions on a case-by-case basis are warranted related to the risk for disease exacerbation following subsequent vaccinations.

The clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation of our patient’s rash were consistent with PG. The temporal relationship between vaccine administration and PG lesion onset suggests the mRNA vaccine triggered AIBD in our patient. Interestingly, AIBD associated with COVID-19 is not unique to only the vaccines and has been observed following infection with the virus itself.14 The high rate of vaccination against COVID-19 in contrast with the low number of reported cases of AIBD after vaccination supports the overall safety of COVID-19 vaccines but identifies a need for further understanding of the processes that lead to the development of autoimmune conditions in at-risk populations.

- Wiznia LE, Pomeranz MK. Skin changes and diseases in pregnancy. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Masmoudi W, Vaillant M, Vassileva S, et al. International validation of the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index severity score and calculation of cut-off values for defining mild, moderate and severe types of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:1106-1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.19611

- Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:138-144.

- Savervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:441-449.

- Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

- Lipozencic J, Ljubojevic S, Bukvic-Mokos Z. Pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:51-55.

- de Lorenzi C, Kaya G, Toutous Trellu L. Pseudo-pemphigoid gestationis eruption following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with mRNA vaccine. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:203-206. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9030025

- McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:113-121.

- Solimani F, Mansour Y, Didona D, et al. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E649-E651.

- Tomayko MM, Damsky W, Fathy R, et al. Subepidermal blistering eruptions, including bullous pemphigoid, following COVID-19 vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:750-751.

- Coto-Segura P, Fernandez-Prada M, Mir-Bonafe M, et al. Vesiculobullous skin reactions induced by COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:141-143.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Woodley DT. Association between vaccination and autoimmune bullous diseases: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1160-1164.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Olson N, Eckhardt D, Delano A. New-onset bullous pemphigoid in a COVID-19 patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2021;2021:5575111.

To the Editor:

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG), or gestational pemphigoid, is a rare autoimmune bullous disease (AIBD) occurring in 1 in 50,000 pregnancies. It is characterized by abrupt development of intensely pruritic papules and urticarial plaques, followed by an eruption of blisters.1 We present a case of new-onset PG that erupted 10 days following SARs-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech).

A 36-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 1, para 0, aborta 0) at 37 weeks’ gestation presented to our AIBD clinic with a pruritic dermatitis of 6 weeks’ duration that developed 10 days after receiving the second dose of BNT162b2. Multiple intensely pruritic, red bumps presented first on the forearms and within days spread to the thighs, hands, and abdomen, followed by progression to the ankles, feet, and back 2 weeks later. An initial biopsy was consistent with subacute spongiotic dermatitis with rare eosinophils. She found minimal relief from diphenhydramine or topical steroids. She denied oral, nasal, ocular, or genital involvement or history of any other skin disease. The pregnancy had been otherwise uneventful.

Physical examination revealed annular edematous plaques on the trunk and buttocks; excoriated and erythematous papules on the neck, trunk, arms, and legs; and scattered vesicles along the fingers, arms, hands, abdomen, back, legs, and feet (Figure 1). The Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) total skin activity score was 25.3, corresponding to moderate disease activity (validated at 20–56).2 The BPDAI total pruritus component score was 20. A repeat biopsy for direct immunofluorescence showed faint linear deposits of IgG and bright linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of IgG localized to the blister roof of salt-split skin at a dilution of 1:40. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-BP180 was 62 U/mL (negative, <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL), and anti-BP230 autoantibodies were less than 9 U/mL (negative <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL). Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, PG was diagnosed.

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and antihistamines while continuing topical steroids. Pruritus and blistering improved close to delivery. Fetal monitoring with regular biophysical profiles remained normal. The patient delivered a healthy neonate without skin lesions at 40 weeks’ gestation. The disease flared 2 days after delivery, and prednisone was increased to 40 mg and slowly tapered. Two months after delivery, the patient remained on prednisone 10 mg daily with ongoing but reduced blistering and pruritus (Figure 2). The BPDAI total skin activity and pruritus component scores remained elevated at 20.3 and 14, respectively, and anti-BP180 was 44 U/mL. After a discussion with the patient on safe systemic therapy while breastfeeding, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was initiated. The patient received 3 monthly infusions at 2 g/kg and was able to taper the prednisone to 5 mg every other day without new lesions. Four months after completion of IVIG therapy, she achieved complete remission off all therapy.

Management of PG begins with topical corticosteroids, but most patients require systemic steroid therapy.1 Remission commonly occurs close to delivery, and 75% of patients flare post partum, though the disease typically resolves 6 months following delivery.1,3,4 For persistent intrapartum cases requiring more than prednisone 20 mg daily, therapy can include dapsone, IVIG, azathioprine, rituximab, or plasmapheresis.4,5 Dapsone and IVIG are compatible with breastfeeding postpartum, but if dapsone is selected, the infant must be monitored for hemolytic anemia.5 Pemphigoid gestationis increases the risk for a premature or small-for-gestational-age neonate, necessitating regular fetal monitoring until delivery.1 Cutaneous lesions may affect the newborn, though this occurrence is rare and self-limiting.6Pemphigoid gestationis may recur in subsequent pregnancies at a rate of 33% to 55%, with earlier and more severe presentations.4

Clinically and histologically, PG closely resembles bullous pemphigoid (BP), but the exact pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recently, another case of what was termed pseudo-PG has been described 3 days following administration of the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.7 Since the introduction of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, cases of postvaccination BP, BP-like eruptions, and pemphigus vulgaris have been described.8-11 Tomayko et al10 reported 12 cases of subepidermal eruptions, including BP, in which 7 patients developed blisters after the second dose of either the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccine. Three patients who developed BP after the first dose of the vaccine and chose to receive the second dose tolerated it well, with a mild flare observed in 1 patient.10 Similarly, subsequent vaccine doses in reports of vaccine-associated AIBD resulted in increased disease activity in 21% of cases.12 COVID-19 vaccine–associated BP, similar to drug-induced BP, seemingly displays a milder course of disease compared to the classic form of BP.10,13 More follow-up is needed to better understand these reactions and inform appropriate discussions on the administration of booster doses. Currently, completion of the vaccination series against COVID-19 is advisable given the paucity of reports of postvaccination AIBD and the risk for COVID-19 infection, but careful discussions on a case-by-case basis are warranted related to the risk for disease exacerbation following subsequent vaccinations.

The clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation of our patient’s rash were consistent with PG. The temporal relationship between vaccine administration and PG lesion onset suggests the mRNA vaccine triggered AIBD in our patient. Interestingly, AIBD associated with COVID-19 is not unique to only the vaccines and has been observed following infection with the virus itself.14 The high rate of vaccination against COVID-19 in contrast with the low number of reported cases of AIBD after vaccination supports the overall safety of COVID-19 vaccines but identifies a need for further understanding of the processes that lead to the development of autoimmune conditions in at-risk populations.

To the Editor:

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG), or gestational pemphigoid, is a rare autoimmune bullous disease (AIBD) occurring in 1 in 50,000 pregnancies. It is characterized by abrupt development of intensely pruritic papules and urticarial plaques, followed by an eruption of blisters.1 We present a case of new-onset PG that erupted 10 days following SARs-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech).

A 36-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 1, para 0, aborta 0) at 37 weeks’ gestation presented to our AIBD clinic with a pruritic dermatitis of 6 weeks’ duration that developed 10 days after receiving the second dose of BNT162b2. Multiple intensely pruritic, red bumps presented first on the forearms and within days spread to the thighs, hands, and abdomen, followed by progression to the ankles, feet, and back 2 weeks later. An initial biopsy was consistent with subacute spongiotic dermatitis with rare eosinophils. She found minimal relief from diphenhydramine or topical steroids. She denied oral, nasal, ocular, or genital involvement or history of any other skin disease. The pregnancy had been otherwise uneventful.

Physical examination revealed annular edematous plaques on the trunk and buttocks; excoriated and erythematous papules on the neck, trunk, arms, and legs; and scattered vesicles along the fingers, arms, hands, abdomen, back, legs, and feet (Figure 1). The Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) total skin activity score was 25.3, corresponding to moderate disease activity (validated at 20–56).2 The BPDAI total pruritus component score was 20. A repeat biopsy for direct immunofluorescence showed faint linear deposits of IgG and bright linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of IgG localized to the blister roof of salt-split skin at a dilution of 1:40. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-BP180 was 62 U/mL (negative, <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL), and anti-BP230 autoantibodies were less than 9 U/mL (negative <9 U/mL; positive, ≥9 U/mL). Given these clinical and histopathologic findings, PG was diagnosed.

The patient was started on prednisone 20 mg and antihistamines while continuing topical steroids. Pruritus and blistering improved close to delivery. Fetal monitoring with regular biophysical profiles remained normal. The patient delivered a healthy neonate without skin lesions at 40 weeks’ gestation. The disease flared 2 days after delivery, and prednisone was increased to 40 mg and slowly tapered. Two months after delivery, the patient remained on prednisone 10 mg daily with ongoing but reduced blistering and pruritus (Figure 2). The BPDAI total skin activity and pruritus component scores remained elevated at 20.3 and 14, respectively, and anti-BP180 was 44 U/mL. After a discussion with the patient on safe systemic therapy while breastfeeding, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was initiated. The patient received 3 monthly infusions at 2 g/kg and was able to taper the prednisone to 5 mg every other day without new lesions. Four months after completion of IVIG therapy, she achieved complete remission off all therapy.

Management of PG begins with topical corticosteroids, but most patients require systemic steroid therapy.1 Remission commonly occurs close to delivery, and 75% of patients flare post partum, though the disease typically resolves 6 months following delivery.1,3,4 For persistent intrapartum cases requiring more than prednisone 20 mg daily, therapy can include dapsone, IVIG, azathioprine, rituximab, or plasmapheresis.4,5 Dapsone and IVIG are compatible with breastfeeding postpartum, but if dapsone is selected, the infant must be monitored for hemolytic anemia.5 Pemphigoid gestationis increases the risk for a premature or small-for-gestational-age neonate, necessitating regular fetal monitoring until delivery.1 Cutaneous lesions may affect the newborn, though this occurrence is rare and self-limiting.6Pemphigoid gestationis may recur in subsequent pregnancies at a rate of 33% to 55%, with earlier and more severe presentations.4

Clinically and histologically, PG closely resembles bullous pemphigoid (BP), but the exact pathogenesis is not fully understood. Recently, another case of what was termed pseudo-PG has been described 3 days following administration of the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.7 Since the introduction of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, cases of postvaccination BP, BP-like eruptions, and pemphigus vulgaris have been described.8-11 Tomayko et al10 reported 12 cases of subepidermal eruptions, including BP, in which 7 patients developed blisters after the second dose of either the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna mRNA vaccine. Three patients who developed BP after the first dose of the vaccine and chose to receive the second dose tolerated it well, with a mild flare observed in 1 patient.10 Similarly, subsequent vaccine doses in reports of vaccine-associated AIBD resulted in increased disease activity in 21% of cases.12 COVID-19 vaccine–associated BP, similar to drug-induced BP, seemingly displays a milder course of disease compared to the classic form of BP.10,13 More follow-up is needed to better understand these reactions and inform appropriate discussions on the administration of booster doses. Currently, completion of the vaccination series against COVID-19 is advisable given the paucity of reports of postvaccination AIBD and the risk for COVID-19 infection, but careful discussions on a case-by-case basis are warranted related to the risk for disease exacerbation following subsequent vaccinations.

The clinical presentation and diagnostic evaluation of our patient’s rash were consistent with PG. The temporal relationship between vaccine administration and PG lesion onset suggests the mRNA vaccine triggered AIBD in our patient. Interestingly, AIBD associated with COVID-19 is not unique to only the vaccines and has been observed following infection with the virus itself.14 The high rate of vaccination against COVID-19 in contrast with the low number of reported cases of AIBD after vaccination supports the overall safety of COVID-19 vaccines but identifies a need for further understanding of the processes that lead to the development of autoimmune conditions in at-risk populations.

- Wiznia LE, Pomeranz MK. Skin changes and diseases in pregnancy. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Masmoudi W, Vaillant M, Vassileva S, et al. International validation of the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index severity score and calculation of cut-off values for defining mild, moderate and severe types of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:1106-1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.19611

- Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:138-144.

- Savervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:441-449.

- Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

- Lipozencic J, Ljubojevic S, Bukvic-Mokos Z. Pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:51-55.

- de Lorenzi C, Kaya G, Toutous Trellu L. Pseudo-pemphigoid gestationis eruption following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with mRNA vaccine. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:203-206. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9030025

- McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:113-121.

- Solimani F, Mansour Y, Didona D, et al. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E649-E651.

- Tomayko MM, Damsky W, Fathy R, et al. Subepidermal blistering eruptions, including bullous pemphigoid, following COVID-19 vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:750-751.

- Coto-Segura P, Fernandez-Prada M, Mir-Bonafe M, et al. Vesiculobullous skin reactions induced by COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:141-143.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Woodley DT. Association between vaccination and autoimmune bullous diseases: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1160-1164.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Olson N, Eckhardt D, Delano A. New-onset bullous pemphigoid in a COVID-19 patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2021;2021:5575111.

- Wiznia LE, Pomeranz MK. Skin changes and diseases in pregnancy. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2019.

- Masmoudi W, Vaillant M, Vassileva S, et al. International validation of the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index severity score and calculation of cut-off values for defining mild, moderate and severe types of bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:1106-1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.19611

- Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:138-144.

- Savervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:441-449.

- Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354-363.

- Lipozencic J, Ljubojevic S, Bukvic-Mokos Z. Pemphigoid gestationis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:51-55.

- de Lorenzi C, Kaya G, Toutous Trellu L. Pseudo-pemphigoid gestationis eruption following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with mRNA vaccine. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:203-206. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9030025

- McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:113-121.

- Solimani F, Mansour Y, Didona D, et al. Development of severe pemphigus vulgaris following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination with BNT162b2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E649-E651.

- Tomayko MM, Damsky W, Fathy R, et al. Subepidermal blistering eruptions, including bullous pemphigoid, following COVID-19 vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148:750-751.

- Coto-Segura P, Fernandez-Prada M, Mir-Bonafe M, et al. Vesiculobullous skin reactions induced by COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:141-143.

- Kasperkiewicz M, Woodley DT. Association between vaccination and autoimmune bullous diseases: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1160-1164.

- Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133-1140.

- Olson N, Eckhardt D, Delano A. New-onset bullous pemphigoid in a COVID-19 patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2021;2021:5575111.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware that COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccinations may present with various cutaneous complications.

- Pemphigoid gestationis should be considered in a pregnant or postpartum woman with an unexplained eruption of persistent, pruritic, urticarial lesions and blisters occurring postvaccination. Treatments include high-potency topical steroids and frequently systemic corticosteroids, along with steroid-sparing agents in severe cases.

Papular Reticulated Rash

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

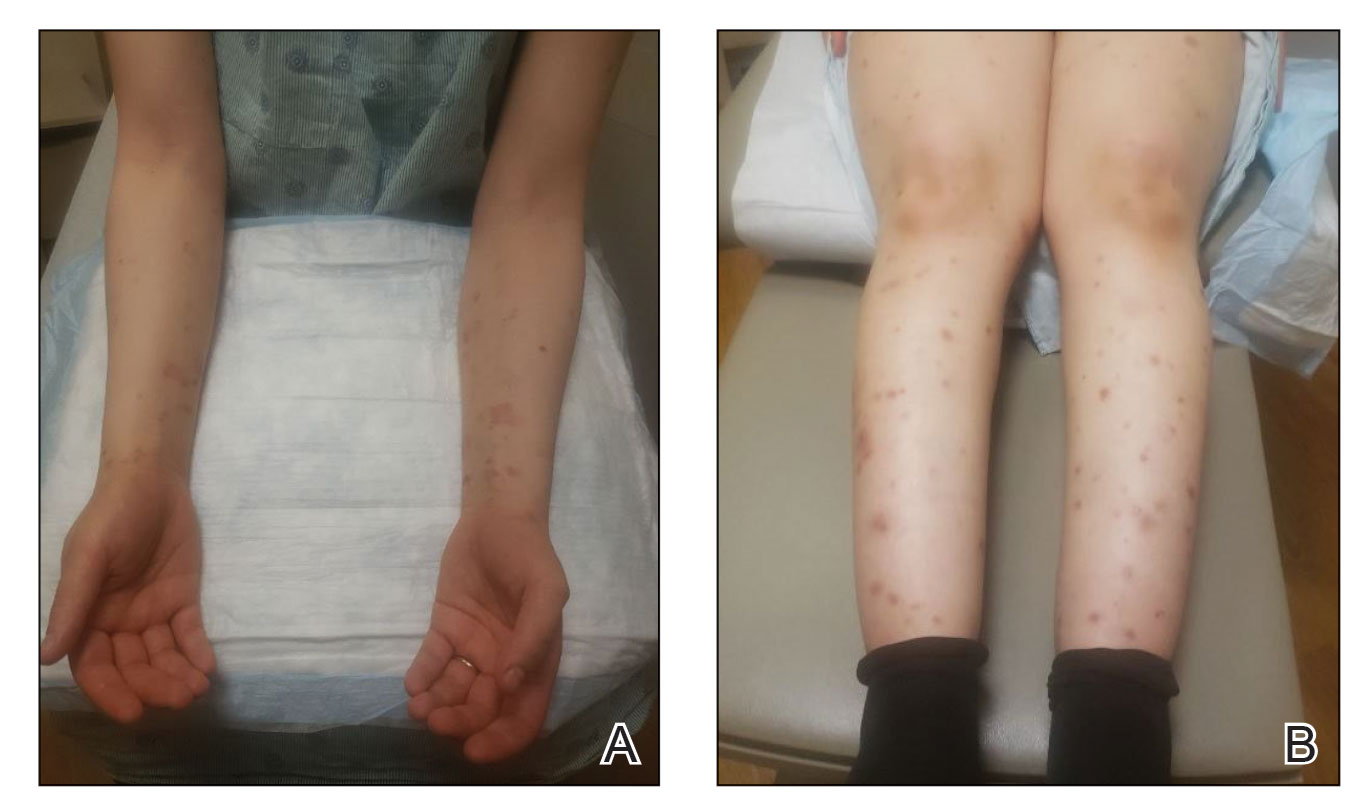

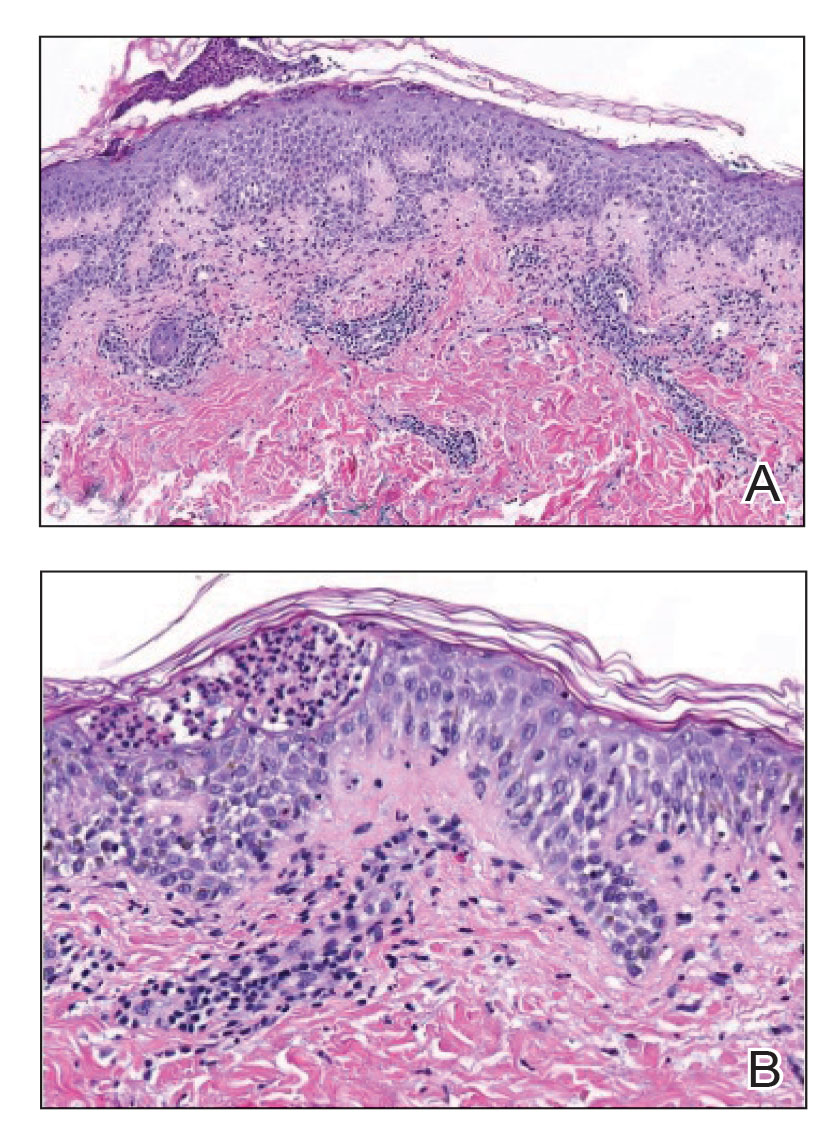

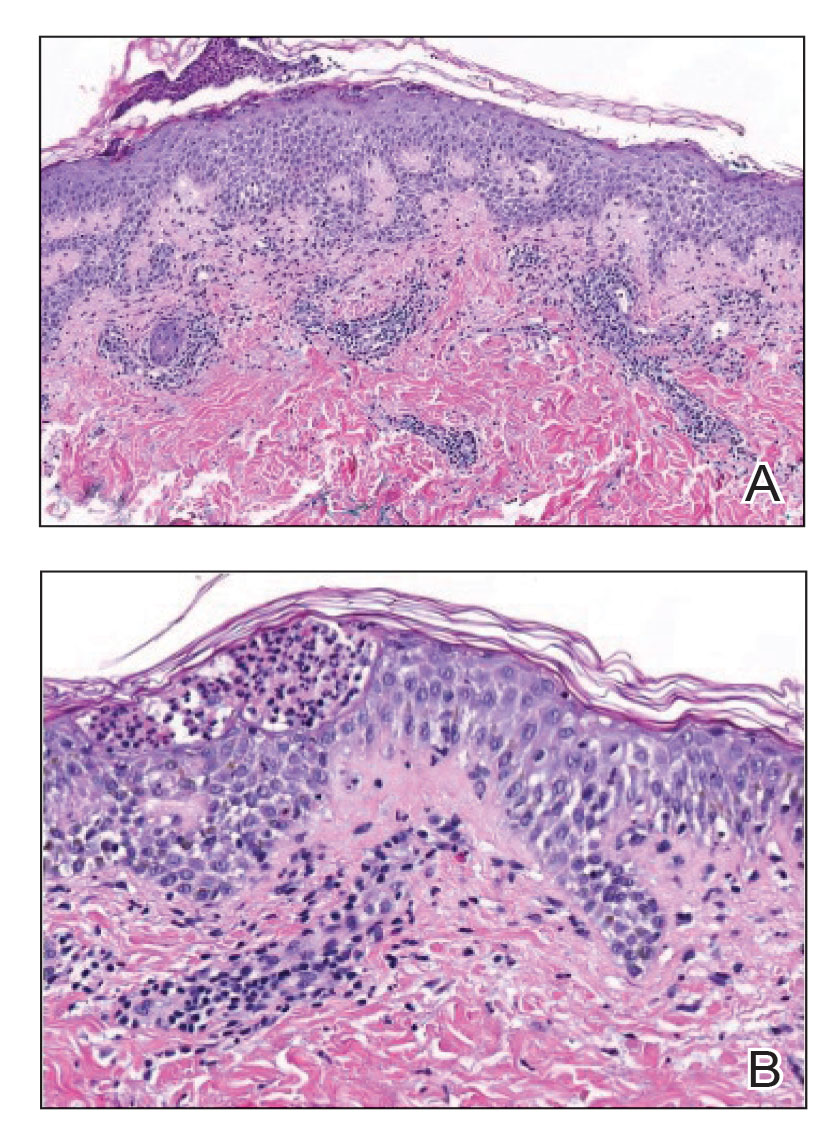

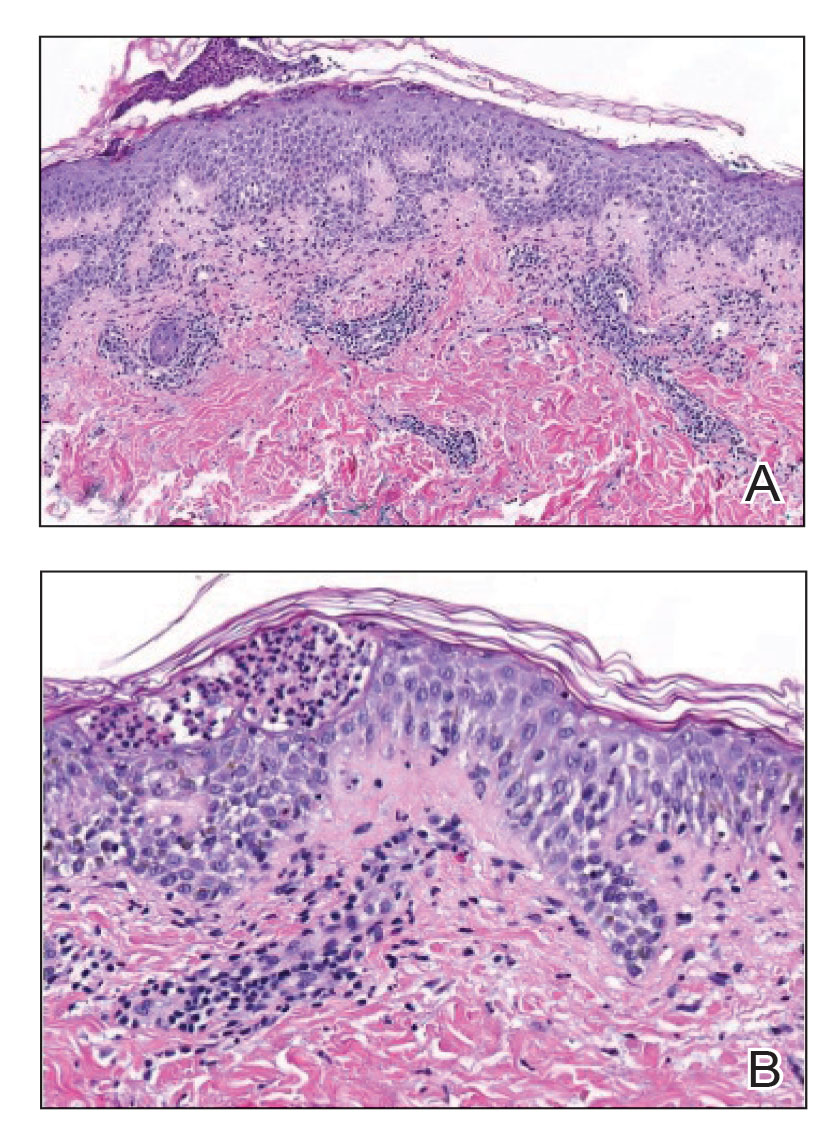

Histopathology of the punch biopsy revealed subcorneal collections of neutrophils flanked by a spongiotic epidermis with neutrophil and eosinophil exocytosis. Rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes were identified at the dermoepidermal junction, and grampositive bacterial organisms were seen in a follicular infundibulum with purulent inflammation. The dermis demonstrated a mildly dense superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and eosinophils (Figure).

Given the combination of clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa (PP) was rendered and a urinalysis was ordered, which confirmed ketonuria. The patient was started on minocycline 100 mg twice daily and was advised to reintroduce carbohydrates into her diet. Resolution of the inflammatory component of the rash was achieved at 3-week follow-up, with residual reticulated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare, albeit globally underrecognized, inflammatory dermatosis characterized by pruritic, symmetric, erythematous papules and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and rarely the arms and forehead that subsequently involute, leaving reticular postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.1 Prurigo pigmentosa is predominant in females (2.6:1 ratio). The mean age at presentation is 24.4 years, and it most commonly has been documented among populations in Asian countries, though it is unclear if a genetic predilection exists, as reports of PP are increasing globally with improved clinical awareness.1,2

The etiology of PP remains unknown; however, associations are well documented between PP and a ketogenic state secondary to uncontrolled diabetes, a low-carbohydrate diet, anorexia nervosa, or bariatric surgery.3 It is theorized that high serum ketones lead to perivascular ketone deposition, which induces neutrophil migration and chemotaxis,4 as substantiated by evidence of rash resolution with correction of the ketogenic state and improvement after administration of tetracyclines, a drug class known for neutrophil chemotaxis inhibition.5 Improvement of PP via these treatment mechanisms suggests that ketone bodies may play a role in the pathogenesis of PP.

Interestingly, Kafle et al6 reported that patients with PP commonly have bacterial colonies and associated inflammatory sequelae at the level of the hair follicles, which suggests that follicular involvement plays a role in the pathogenesis of PP. These findings are consistent with our patient’s histopathology consisting of gram-positive organisms and purulent inflammation at the infundibulum. The histopathologic features of PP are stage specific.1 Early stages are characterized by a superficial perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils that then spread to dermal papillae. Neutrophils then quickly sweep through the epidermis, causing spongiosis, ballooning, necrotic keratocytes, and consequent surface epithelium abscess formation. Over time, the dermal infiltrate assumes a lichenoid pattern as eosinophils and lymphocytes invade and predominate over neutrophils. Eventually, melanophages appear in the dermis as the epidermis undergoes hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and hyperpigmentation.1 The histologic differential diagnosis for PP is broad and varies based on the stage-specific progression of clinical and histopathologic findings.

Similar to PP, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has a female predominance and resolves with subsequent dyspigmentation; however, it initially is characterized by annular plaques with central clearing or papulosquamous lesions restricted to sun-exposed skin. Photosensitivity is a prominent feature, and roughly 50% of patients meet diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.7 Histopathology shows interface changes with increased dermal mucin and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Papular pityriasis rosea can present as a pruritic papular rash on the back and chest; however, it most commonly is associated with a herald patch and typically follows a flulike prodrome.8 Biopsy reveals mounds of parakeratosis with mild spongiosis, perivascular inflammation, and extravasated erythrocytes.

Galli-Galli disease can present as a pruritic rash with follicular papules under the breasts and other flexural areas but histopathologically shows elongated rete ridges with dermal melanosis and acantholysis.9

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly presents in the third decade of life and can manifest as painful, pruritic, vesicular lesions on erythematous skin distributed on the back, neck, and inframammary region, as seen in our case; however, it is histopathologically associated with widespread epidermal acantholysis unlike the findings seen in our patient.10

First-line treatment of PP includes antibiotics such as minocycline, doxycycline, and dapsone due to their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis. In patients with nutritional deficiencies or ketosis, reintroduction of carbohydrates alone has been effective.5,11

Prurigo pigmentosa is an underrecognized inflammatory dermatosis with a complex stage-dependent clinicopathologic presentation. Clinicians should be aware of the etiologic and histopathologic patterns of this unique dermatosis. Rash presentation in the context of a low-carbohydrate diet should prompt biopsy as well as treatment with antibiotics and dietary reintroduction of carbohydrates.

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- de Sousa Vargas TJ, Abreu Raposo CM, Lima RB, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: report of 3 cases from Brazil and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:267-274. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000643

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79. doi:10.1016/J .JDIN.2021.03.003

- Beutler BD, Cohen PR, Lee RA. Prurigo pigmentosa: literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:533-543. doi:10.1007/S40257-015-0154-4

- Chiam LYT, Goh BK, Lim KS, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a report of two cases that responded to minocycline. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2230.2009.03253.X

- Kafle SU, Swe SM, Hsiao PF, et al. Folliculitis in prurigo pigmentosa: a proposed pathogenesis based on clinical and pathological observation. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:20-27. doi:10.1111/CUP.12829

- Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263. doi:10.1016/J .AUTREV.2004.10.00

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:201-211. doi:10.2174/15733963166662 00923161330

- Sprecher E, Indelman M, Khamaysi Z, et al. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:572-574. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.2006.07703.X

- Burge SM. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:275-282. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1992.TB00658

- Lu L-Y, Chen C-B. Keto rash: ketoacidosis-induced prurigo pigmentosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.019

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

Histopathology of the punch biopsy revealed subcorneal collections of neutrophils flanked by a spongiotic epidermis with neutrophil and eosinophil exocytosis. Rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes were identified at the dermoepidermal junction, and grampositive bacterial organisms were seen in a follicular infundibulum with purulent inflammation. The dermis demonstrated a mildly dense superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and eosinophils (Figure).

Given the combination of clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa (PP) was rendered and a urinalysis was ordered, which confirmed ketonuria. The patient was started on minocycline 100 mg twice daily and was advised to reintroduce carbohydrates into her diet. Resolution of the inflammatory component of the rash was achieved at 3-week follow-up, with residual reticulated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare, albeit globally underrecognized, inflammatory dermatosis characterized by pruritic, symmetric, erythematous papules and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and rarely the arms and forehead that subsequently involute, leaving reticular postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.1 Prurigo pigmentosa is predominant in females (2.6:1 ratio). The mean age at presentation is 24.4 years, and it most commonly has been documented among populations in Asian countries, though it is unclear if a genetic predilection exists, as reports of PP are increasing globally with improved clinical awareness.1,2

The etiology of PP remains unknown; however, associations are well documented between PP and a ketogenic state secondary to uncontrolled diabetes, a low-carbohydrate diet, anorexia nervosa, or bariatric surgery.3 It is theorized that high serum ketones lead to perivascular ketone deposition, which induces neutrophil migration and chemotaxis,4 as substantiated by evidence of rash resolution with correction of the ketogenic state and improvement after administration of tetracyclines, a drug class known for neutrophil chemotaxis inhibition.5 Improvement of PP via these treatment mechanisms suggests that ketone bodies may play a role in the pathogenesis of PP.

Interestingly, Kafle et al6 reported that patients with PP commonly have bacterial colonies and associated inflammatory sequelae at the level of the hair follicles, which suggests that follicular involvement plays a role in the pathogenesis of PP. These findings are consistent with our patient’s histopathology consisting of gram-positive organisms and purulent inflammation at the infundibulum. The histopathologic features of PP are stage specific.1 Early stages are characterized by a superficial perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils that then spread to dermal papillae. Neutrophils then quickly sweep through the epidermis, causing spongiosis, ballooning, necrotic keratocytes, and consequent surface epithelium abscess formation. Over time, the dermal infiltrate assumes a lichenoid pattern as eosinophils and lymphocytes invade and predominate over neutrophils. Eventually, melanophages appear in the dermis as the epidermis undergoes hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and hyperpigmentation.1 The histologic differential diagnosis for PP is broad and varies based on the stage-specific progression of clinical and histopathologic findings.

Similar to PP, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has a female predominance and resolves with subsequent dyspigmentation; however, it initially is characterized by annular plaques with central clearing or papulosquamous lesions restricted to sun-exposed skin. Photosensitivity is a prominent feature, and roughly 50% of patients meet diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.7 Histopathology shows interface changes with increased dermal mucin and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Papular pityriasis rosea can present as a pruritic papular rash on the back and chest; however, it most commonly is associated with a herald patch and typically follows a flulike prodrome.8 Biopsy reveals mounds of parakeratosis with mild spongiosis, perivascular inflammation, and extravasated erythrocytes.

Galli-Galli disease can present as a pruritic rash with follicular papules under the breasts and other flexural areas but histopathologically shows elongated rete ridges with dermal melanosis and acantholysis.9

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly presents in the third decade of life and can manifest as painful, pruritic, vesicular lesions on erythematous skin distributed on the back, neck, and inframammary region, as seen in our case; however, it is histopathologically associated with widespread epidermal acantholysis unlike the findings seen in our patient.10

First-line treatment of PP includes antibiotics such as minocycline, doxycycline, and dapsone due to their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis. In patients with nutritional deficiencies or ketosis, reintroduction of carbohydrates alone has been effective.5,11

Prurigo pigmentosa is an underrecognized inflammatory dermatosis with a complex stage-dependent clinicopathologic presentation. Clinicians should be aware of the etiologic and histopathologic patterns of this unique dermatosis. Rash presentation in the context of a low-carbohydrate diet should prompt biopsy as well as treatment with antibiotics and dietary reintroduction of carbohydrates.

The Diagnosis: Prurigo Pigmentosa

Histopathology of the punch biopsy revealed subcorneal collections of neutrophils flanked by a spongiotic epidermis with neutrophil and eosinophil exocytosis. Rare dyskeratotic keratinocytes were identified at the dermoepidermal junction, and grampositive bacterial organisms were seen in a follicular infundibulum with purulent inflammation. The dermis demonstrated a mildly dense superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and eosinophils (Figure).

Given the combination of clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of prurigo pigmentosa (PP) was rendered and a urinalysis was ordered, which confirmed ketonuria. The patient was started on minocycline 100 mg twice daily and was advised to reintroduce carbohydrates into her diet. Resolution of the inflammatory component of the rash was achieved at 3-week follow-up, with residual reticulated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare, albeit globally underrecognized, inflammatory dermatosis characterized by pruritic, symmetric, erythematous papules and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and rarely the arms and forehead that subsequently involute, leaving reticular postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.1 Prurigo pigmentosa is predominant in females (2.6:1 ratio). The mean age at presentation is 24.4 years, and it most commonly has been documented among populations in Asian countries, though it is unclear if a genetic predilection exists, as reports of PP are increasing globally with improved clinical awareness.1,2

The etiology of PP remains unknown; however, associations are well documented between PP and a ketogenic state secondary to uncontrolled diabetes, a low-carbohydrate diet, anorexia nervosa, or bariatric surgery.3 It is theorized that high serum ketones lead to perivascular ketone deposition, which induces neutrophil migration and chemotaxis,4 as substantiated by evidence of rash resolution with correction of the ketogenic state and improvement after administration of tetracyclines, a drug class known for neutrophil chemotaxis inhibition.5 Improvement of PP via these treatment mechanisms suggests that ketone bodies may play a role in the pathogenesis of PP.

Interestingly, Kafle et al6 reported that patients with PP commonly have bacterial colonies and associated inflammatory sequelae at the level of the hair follicles, which suggests that follicular involvement plays a role in the pathogenesis of PP. These findings are consistent with our patient’s histopathology consisting of gram-positive organisms and purulent inflammation at the infundibulum. The histopathologic features of PP are stage specific.1 Early stages are characterized by a superficial perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils that then spread to dermal papillae. Neutrophils then quickly sweep through the epidermis, causing spongiosis, ballooning, necrotic keratocytes, and consequent surface epithelium abscess formation. Over time, the dermal infiltrate assumes a lichenoid pattern as eosinophils and lymphocytes invade and predominate over neutrophils. Eventually, melanophages appear in the dermis as the epidermis undergoes hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and hyperpigmentation.1 The histologic differential diagnosis for PP is broad and varies based on the stage-specific progression of clinical and histopathologic findings.

Similar to PP, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has a female predominance and resolves with subsequent dyspigmentation; however, it initially is characterized by annular plaques with central clearing or papulosquamous lesions restricted to sun-exposed skin. Photosensitivity is a prominent feature, and roughly 50% of patients meet diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.7 Histopathology shows interface changes with increased dermal mucin and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate.

Papular pityriasis rosea can present as a pruritic papular rash on the back and chest; however, it most commonly is associated with a herald patch and typically follows a flulike prodrome.8 Biopsy reveals mounds of parakeratosis with mild spongiosis, perivascular inflammation, and extravasated erythrocytes.

Galli-Galli disease can present as a pruritic rash with follicular papules under the breasts and other flexural areas but histopathologically shows elongated rete ridges with dermal melanosis and acantholysis.9

Hailey-Hailey disease commonly presents in the third decade of life and can manifest as painful, pruritic, vesicular lesions on erythematous skin distributed on the back, neck, and inframammary region, as seen in our case; however, it is histopathologically associated with widespread epidermal acantholysis unlike the findings seen in our patient.10

First-line treatment of PP includes antibiotics such as minocycline, doxycycline, and dapsone due to their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis. In patients with nutritional deficiencies or ketosis, reintroduction of carbohydrates alone has been effective.5,11

Prurigo pigmentosa is an underrecognized inflammatory dermatosis with a complex stage-dependent clinicopathologic presentation. Clinicians should be aware of the etiologic and histopathologic patterns of this unique dermatosis. Rash presentation in the context of a low-carbohydrate diet should prompt biopsy as well as treatment with antibiotics and dietary reintroduction of carbohydrates.

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- de Sousa Vargas TJ, Abreu Raposo CM, Lima RB, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: report of 3 cases from Brazil and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:267-274. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000643

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79. doi:10.1016/J .JDIN.2021.03.003

- Beutler BD, Cohen PR, Lee RA. Prurigo pigmentosa: literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:533-543. doi:10.1007/S40257-015-0154-4

- Chiam LYT, Goh BK, Lim KS, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a report of two cases that responded to minocycline. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2230.2009.03253.X

- Kafle SU, Swe SM, Hsiao PF, et al. Folliculitis in prurigo pigmentosa: a proposed pathogenesis based on clinical and pathological observation. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:20-27. doi:10.1111/CUP.12829

- Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263. doi:10.1016/J .AUTREV.2004.10.00

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:201-211. doi:10.2174/15733963166662 00923161330

- Sprecher E, Indelman M, Khamaysi Z, et al. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:572-574. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.2006.07703.X

- Burge SM. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:275-282. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1992.TB00658

- Lu L-Y, Chen C-B. Keto rash: ketoacidosis-induced prurigo pigmentosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.019

- Böer A, Misago N, Wolter M, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:117-129. doi:10.1097/00000372-200304000-00005

- de Sousa Vargas TJ, Abreu Raposo CM, Lima RB, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: report of 3 cases from Brazil and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:267-274. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000643

- Mufti A, Mirali S, Abduelmula A, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes in prurigo pigmentosa (Nagashima disease): a systematic review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2021;3:79. doi:10.1016/J .JDIN.2021.03.003

- Beutler BD, Cohen PR, Lee RA. Prurigo pigmentosa: literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:533-543. doi:10.1007/S40257-015-0154-4

- Chiam LYT, Goh BK, Lim KS, et al. Prurigo pigmentosa: a report of two cases that responded to minocycline. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2230.2009.03253.X

- Kafle SU, Swe SM, Hsiao PF, et al. Folliculitis in prurigo pigmentosa: a proposed pathogenesis based on clinical and pathological observation. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:20-27. doi:10.1111/CUP.12829

- Sontheimer RD. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: 25-year evolution of a prototypic subset (subphenotype) of lupus erythematosus defined by characteristic cutaneous, pathological, immunological, and genetic findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:253-263. doi:10.1016/J .AUTREV.2004.10.00

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Pityriasis rosea: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:201-211. doi:10.2174/15733963166662 00923161330

- Sprecher E, Indelman M, Khamaysi Z, et al. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:572-574. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.2006.07703.X

- Burge SM. Hailey-Hailey disease: the clinical features, response to treatment and prognosis. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:275-282. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2133.1992.TB00658

- Lu L-Y, Chen C-B. Keto rash: ketoacidosis-induced prurigo pigmentosa. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97:20-21. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.019

An otherwise healthy 22-year-old woman presented with a painful eruption with burning and pruritus that had been slowly worsening as it spread over the last 4 weeks. The rash first appeared on the lower chest and inframammary folds (top) and spread to the upper chest, neck, back (bottom), arms, and lower face. Physical examination revealed multiple illdefined, erythematous papules, patches, and plaques on the chest, back, neck, and upper abdomen. Individual lesions coalesced into plaques that displayed a reticular configuration. There were no lesions in the axillae. The patient had been following a low-carbohydrate diet for 4 months. A punch biopsy was performed.

Low disease state for childhood lupus approaches validation

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – An age-appropriate version of the Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) has been developed by an international task force that will hopefully enable childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) to be treated to target in the near future.

The new childhood LLDAS (cLLDAS) has been purposefully developed to align with that already used for adults, Eve Smith, MBChB, PhD, explained at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

“There’s a lot of compelling data that’s accumulating from adult lupus and increasingly from childhood lupus that [treat to target] might be a good idea,” said Dr. Smith, who is a senior clinical fellow and honorary consultant at the University of Liverpool (England) and Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Hospital, also in Liverpool.

Urgent need to improve childhood lupus outcomes

“We urgently need to do something to try and improve outcomes for children,” Dr. Smith said.

“We know that childhood lupus patients have got higher disease activity as compared to adults; they have a greater medication burden, particularly steroids; and they tend to have more severe organ manifestations,” she added.

Moreover, data show that one-fifth of pediatric patients with lupus have already accrued early damage, and there is much higher mortality associated with childhood lupus than there is with adult lupus.

“So, really we want to use treat to target as a way to try and improve on these aspects,” Dr. Smith said.

The treat-to-target (T2T) approach is not a new idea in lupus, with a lot of work already done in adult patients. One large study of more than 3,300 patients conducted in 13 countries has shown that patients who never achieve LLDAS are more likely to have high levels of damage, greater glucocorticoid use, worse quality of life, and higher mortality than are those who do.

Conversely, data have also shown that achieving a LLDAS is associated with a reduction in the risk for new damage, flares, and hospitalization, as well as reducing health care costs and improving patients’ overall health-related quality of life.

T2T is a recognized approach in European adult SLE guidelines, Dr. Smith said, although the approach has not really been fully realized as of yet, even in adult practice.

The cSLE T2T international task force and cLLDAS definition

With evidence accumulating on the benefits of getting children with SLE to a low disease activity state, Dr. Smith and colleague Michael Beresford, MBChB, PhD, Brough Chair, Professor of Child Health at the University of Liverpool, put out a call to develop a task force to look into the feasibility of a T2T approach.

“We had a really enthusiastic response internationally, which we were really encouraged by,” Dr. Smith said, “and we now lead a task force of 20 experts from across all five continents, and we have really strong patient involvement.”

Through a consensus process, an international cSLE T2T Task Force agreed on overarching principles and points to consider that will “lay the foundation for future T2T approaches in cSLE,” according to the recommendations statement, which was endorsed by the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society.

Next, they looked to develop an age-appropriate definition for low disease activity.

“We’re deliberately wanting to maintain sufficient unity with the adult definition, so that we could facilitate life-course studies,” said Dr. Smith, who presented the results of a literature review and series of Delphi surveys at the meeting.

The conceptual definition of cLLDAS is similar to adults in describing it as a sustained state that is associated with a low likelihood of adverse outcome, Dr. Smith said, but with the added wording of “considering disease activity, damage, and medication toxicity.”

The definition is achieved when the SLE Disease Activity Index-2K is ≤ 4 and there is no activity in major organ systems; there are no new features of lupus disease activity since the last assessment; there is a score of ≤ 1 on Physician Global Assessment; steroid doses are ≤ 0.15 mg/kg/day or a maximum of 7.5 mg/day (whichever is lower); and immunosuppressive treatment is stable, with any changes to medication only because of side effects, adherence, changes in weight, or when in the process of reaching a target dose.

“It’s all very well having a definition, but you need to think about how that will work in practice,” Dr. Smith said. This is something that the task force is thinking about very carefully.

The task force next aims to validate the cLLDAS definition, form an extensive research agenda to inform the T2T methods, and develop innovative methods to apply the approach in practice.

The work is supported by the Wellcome Trust, National Institutes for Health Research, Versus Arthritis, and the University of Liverpool, Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust and the Alder Hey Charity. Dr. Smith reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – An age-appropriate version of the Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) has been developed by an international task force that will hopefully enable childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) to be treated to target in the near future.

The new childhood LLDAS (cLLDAS) has been purposefully developed to align with that already used for adults, Eve Smith, MBChB, PhD, explained at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

“There’s a lot of compelling data that’s accumulating from adult lupus and increasingly from childhood lupus that [treat to target] might be a good idea,” said Dr. Smith, who is a senior clinical fellow and honorary consultant at the University of Liverpool (England) and Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Hospital, also in Liverpool.

Urgent need to improve childhood lupus outcomes

“We urgently need to do something to try and improve outcomes for children,” Dr. Smith said.

“We know that childhood lupus patients have got higher disease activity as compared to adults; they have a greater medication burden, particularly steroids; and they tend to have more severe organ manifestations,” she added.

Moreover, data show that one-fifth of pediatric patients with lupus have already accrued early damage, and there is much higher mortality associated with childhood lupus than there is with adult lupus.

“So, really we want to use treat to target as a way to try and improve on these aspects,” Dr. Smith said.

The treat-to-target (T2T) approach is not a new idea in lupus, with a lot of work already done in adult patients. One large study of more than 3,300 patients conducted in 13 countries has shown that patients who never achieve LLDAS are more likely to have high levels of damage, greater glucocorticoid use, worse quality of life, and higher mortality than are those who do.

Conversely, data have also shown that achieving a LLDAS is associated with a reduction in the risk for new damage, flares, and hospitalization, as well as reducing health care costs and improving patients’ overall health-related quality of life.

T2T is a recognized approach in European adult SLE guidelines, Dr. Smith said, although the approach has not really been fully realized as of yet, even in adult practice.

The cSLE T2T international task force and cLLDAS definition

With evidence accumulating on the benefits of getting children with SLE to a low disease activity state, Dr. Smith and colleague Michael Beresford, MBChB, PhD, Brough Chair, Professor of Child Health at the University of Liverpool, put out a call to develop a task force to look into the feasibility of a T2T approach.

“We had a really enthusiastic response internationally, which we were really encouraged by,” Dr. Smith said, “and we now lead a task force of 20 experts from across all five continents, and we have really strong patient involvement.”

Through a consensus process, an international cSLE T2T Task Force agreed on overarching principles and points to consider that will “lay the foundation for future T2T approaches in cSLE,” according to the recommendations statement, which was endorsed by the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society.

Next, they looked to develop an age-appropriate definition for low disease activity.

“We’re deliberately wanting to maintain sufficient unity with the adult definition, so that we could facilitate life-course studies,” said Dr. Smith, who presented the results of a literature review and series of Delphi surveys at the meeting.

The conceptual definition of cLLDAS is similar to adults in describing it as a sustained state that is associated with a low likelihood of adverse outcome, Dr. Smith said, but with the added wording of “considering disease activity, damage, and medication toxicity.”

The definition is achieved when the SLE Disease Activity Index-2K is ≤ 4 and there is no activity in major organ systems; there are no new features of lupus disease activity since the last assessment; there is a score of ≤ 1 on Physician Global Assessment; steroid doses are ≤ 0.15 mg/kg/day or a maximum of 7.5 mg/day (whichever is lower); and immunosuppressive treatment is stable, with any changes to medication only because of side effects, adherence, changes in weight, or when in the process of reaching a target dose.

“It’s all very well having a definition, but you need to think about how that will work in practice,” Dr. Smith said. This is something that the task force is thinking about very carefully.

The task force next aims to validate the cLLDAS definition, form an extensive research agenda to inform the T2T methods, and develop innovative methods to apply the approach in practice.

The work is supported by the Wellcome Trust, National Institutes for Health Research, Versus Arthritis, and the University of Liverpool, Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust and the Alder Hey Charity. Dr. Smith reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – An age-appropriate version of the Lupus Low Disease Activity State (LLDAS) has been developed by an international task force that will hopefully enable childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) to be treated to target in the near future.

The new childhood LLDAS (cLLDAS) has been purposefully developed to align with that already used for adults, Eve Smith, MBChB, PhD, explained at the annual meeting of the British Society for Rheumatology.

“There’s a lot of compelling data that’s accumulating from adult lupus and increasingly from childhood lupus that [treat to target] might be a good idea,” said Dr. Smith, who is a senior clinical fellow and honorary consultant at the University of Liverpool (England) and Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust Hospital, also in Liverpool.

Urgent need to improve childhood lupus outcomes

“We urgently need to do something to try and improve outcomes for children,” Dr. Smith said.

“We know that childhood lupus patients have got higher disease activity as compared to adults; they have a greater medication burden, particularly steroids; and they tend to have more severe organ manifestations,” she added.

Moreover, data show that one-fifth of pediatric patients with lupus have already accrued early damage, and there is much higher mortality associated with childhood lupus than there is with adult lupus.

“So, really we want to use treat to target as a way to try and improve on these aspects,” Dr. Smith said.

The treat-to-target (T2T) approach is not a new idea in lupus, with a lot of work already done in adult patients. One large study of more than 3,300 patients conducted in 13 countries has shown that patients who never achieve LLDAS are more likely to have high levels of damage, greater glucocorticoid use, worse quality of life, and higher mortality than are those who do.

Conversely, data have also shown that achieving a LLDAS is associated with a reduction in the risk for new damage, flares, and hospitalization, as well as reducing health care costs and improving patients’ overall health-related quality of life.

T2T is a recognized approach in European adult SLE guidelines, Dr. Smith said, although the approach has not really been fully realized as of yet, even in adult practice.

The cSLE T2T international task force and cLLDAS definition

With evidence accumulating on the benefits of getting children with SLE to a low disease activity state, Dr. Smith and colleague Michael Beresford, MBChB, PhD, Brough Chair, Professor of Child Health at the University of Liverpool, put out a call to develop a task force to look into the feasibility of a T2T approach.

“We had a really enthusiastic response internationally, which we were really encouraged by,” Dr. Smith said, “and we now lead a task force of 20 experts from across all five continents, and we have really strong patient involvement.”

Through a consensus process, an international cSLE T2T Task Force agreed on overarching principles and points to consider that will “lay the foundation for future T2T approaches in cSLE,” according to the recommendations statement, which was endorsed by the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society.

Next, they looked to develop an age-appropriate definition for low disease activity.

“We’re deliberately wanting to maintain sufficient unity with the adult definition, so that we could facilitate life-course studies,” said Dr. Smith, who presented the results of a literature review and series of Delphi surveys at the meeting.

The conceptual definition of cLLDAS is similar to adults in describing it as a sustained state that is associated with a low likelihood of adverse outcome, Dr. Smith said, but with the added wording of “considering disease activity, damage, and medication toxicity.”

The definition is achieved when the SLE Disease Activity Index-2K is ≤ 4 and there is no activity in major organ systems; there are no new features of lupus disease activity since the last assessment; there is a score of ≤ 1 on Physician Global Assessment; steroid doses are ≤ 0.15 mg/kg/day or a maximum of 7.5 mg/day (whichever is lower); and immunosuppressive treatment is stable, with any changes to medication only because of side effects, adherence, changes in weight, or when in the process of reaching a target dose.

“It’s all very well having a definition, but you need to think about how that will work in practice,” Dr. Smith said. This is something that the task force is thinking about very carefully.

The task force next aims to validate the cLLDAS definition, form an extensive research agenda to inform the T2T methods, and develop innovative methods to apply the approach in practice.

The work is supported by the Wellcome Trust, National Institutes for Health Research, Versus Arthritis, and the University of Liverpool, Alder Hey Children’s NHS Foundation Trust and the Alder Hey Charity. Dr. Smith reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT BSR 2023

Part-time physician: Is it a viable career choice?

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.

But physicians working part-time express a contrasting point of view. “I don’t believe that part-time workers are responsible for the health care shortage but rather, a great solution,” said Dr. O’Connell. “Because in order to continue working for a long time rather than quitting when the demands exceed human capacity, working part time is a great compromise to offer a life of more sustainable well-being and longevity as a physician, and still live a wholehearted life.”

Pros and cons of being a part-time physician

Pros

Less burnout: The American Medical Association has tracked burnout rates for 22 years. By the end of 2021, nearly 63% of physicians reported burnout symptoms, compared with 38% the year before. Going part time appears to reduce burnout, suggests a study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Better work-life balance: Rachel Miller, MD, an ob.gyn., worked 60-70 hours weekly for 9 years. In 2022, she went to work as an OB hospitalist for a health care system that welcomes part-time clinicians. Since then, she has achieved a better work-life balance, putting in 26-28 hours a week. Dr. Miller now spends more time with her kids and in her additional role as an executive coach to leaders in the medical field.

More focus: “When I’m at work, I’m 100% mentally in and focused,” said Dr. Miller. “My interactions with patients are different because I’m not burned out. My demeanor and my willingness to connect are stronger.”

Better health: Mehmet Cilingiroglu, MD, with CardioSolution, traded full-time work for part time when health issues and a kidney transplant sidelined his 30-year career in 2018. “Despite my significant health issues, I’ve been able to continue working at a pace that suits me rather than having to retire,” he said. “Part-time physicians can still enjoy patient care, research, innovation, education, and training while balancing that with other areas of life.”

Errin Weisman, a DO who gave up full-time work in 2016, said cutting back makes her feel healthier, happier, and more energized. “Part-time work helps me to bring my A game each day I work and deliver the best care.” She’s also a life coach encouraging other physicians to find balance in their professional and personal lives.

Cons

Cut in pay: Obviously, the No. 1 con is you’ll make less working part time, so adjusting to a salary decrease can be a huge issue, especially if you don’t have other sources of income. Physicians paying off student loans, those caring for children or elderly parents, or those in their prime earning years needing to save for retirement may not be able to go part time.

Diminished career: The chance for promotions or being well known in your field can be diminished, as well as a loss of proficiency if you’re only performing surgery or procedures part time. In some specialties, working part time and not keeping up with (or being able to practice) newer technology developments can harm your career or reputation in the long run.

Missing out: While working part time has many benefits, physicians also experience a wide range of drawbacks. Dr. Goodman, for example, said she misses delivering babies and doing surgeries. Dr. Miller said she gave up some aspects of her specialty, like performing hysterectomies, participating in complex cases, and no longer having an office like she did as a full-time ob.gyn.

Loss of fellowship: Dr. O’Connell said she missed the camaraderie and sense of belonging when she scaled back her hours. “I felt like a fish out of water, that my values didn’t align with the group’s values,” she said. This led to self-doubt, frustrated colleagues, and a reduction in benefits.

Lost esteem: Dr. O’Connell also felt she was expected to work overtime without additional pay and was no longer eligible for bonuses. “I was treated as a team player when I was needed, but not when it came to perks and benefits and insider privilege,” she said. There may be a loss of esteem among colleagues and supervisors.

Overcoming stigma: Because part-time physician work is still not prevalent among colleagues, some may resist the idea, have less respect for it, perceive it as not being serious about your career as a physician, or associate it with being lazy or entitled.

Summing it up

Every physician must weigh the value and drawbacks of part-time work, but the more physicians who go this route, the more part-time medicine gains traction and the more physicians can learn about its values versus its drawbacks.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

On average, physicians reported in the Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2023 that they worked 50 hours per week. Five specialties, including critical care, cardiology, and general surgery reported working 55 or more hours weekly.

In 2011, The New England Journal of Medicine reported that part-time physician careers were rising. At the time, part-time doctors made up 21% of the physician workforce, up from 13% in 2005.

In a more recent survey from the California Health Care Foundation, only 12% of California physicians said they devoted 20-29 hours a week to patient care.

Amy Knoup, a senior recruitment adviser with Provider Solutions & Development), has been helping doctors find jobs for over a decade, and she’s noticed a trend.

“Not only are more physicians seeking part-time roles than they were 10 years ago, but more large health care systems are also offering part time or per diem as well,” said Ms. Knoup.

Who’s working part time, and why?

Ten years ago, the fastest growing segment of part-timers were men nearing retirement and early- to mid-career women.

Pediatricians led the part-time pack in 2002, according to an American Academy of Pediatrics study. At the time, 15% of pediatricians reported their hours as part time. However, the numbers may have increased over the years. For example, a 2021 study by the department of pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, and Boston University found that almost 30% of graduating pediatricians sought part-time work at the end of their training.

At PS&D, Ms. Knoup said she has noticed a trend toward part-timers among primary care, behavioral health, and outpatient specialties such as endocrinology. “We’re also seeing it with the inpatient side in roles that are more shift based like hospitalists, radiologists, and critical care and ER doctors.”

Another trend Ms. Knoup has noticed is with early-career doctors. “They have a different mindset,” she said. “Younger generations are acutely aware of burnout. They may have experienced it in residency or during the pandemic. They’ve had a taste of that and don’t want to go down that road again, so they’re seeking part-time roles. It’s an intentional choice.”

Tracey O’Connell, MD, a radiologist, always knew that she wanted to work part time. “I had a baby as a resident, and I was pregnant with my second child as a fellow,” she said. “I was already feeling overwhelmed with medical training and having a family.”

Dr. O’Connell worked in private practice for 16 years on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, with no nights or weekends.

“I still found it completely overwhelming,” she said. “Even though I had more days not working than working, I felt like the demands of medical life had advanced faster than human beings could adapt, and I still feel that way.”

Today she runs a part-time teleradiology practice from home but spends more time on her second career as a life coach. “Most of my clients are physicians looking for more fulfillment and sustainable ways of practicing medicine while maintaining their own identity as human beings, not just the all-consuming identity of ‘doctor,’ ” she said.

On the other end of the career spectrum is Lois Goodman, MD, an ob.gyn. in her late 70s. After 42 years in a group practice, she started her solo practice at 72, seeing patients 3 days per week. “I’m just happy to be working. That’s a tremendous payoff for me. I need to keep working for my mental health.”

How does part-time work affect physician shortages and care delivery?

Reducing clinical effort is one of the strategies physicians use to scale down overload. Still, it’s not viable as a long-term solution, said Christine Sinsky, MD, AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction and a nationally regarded researcher on physician burnout.

“If all the physicians in a community went from working 100% FTE clinical to 50% FTE clinical, then the people in that community would have half the access to care that they had,” said Dr. Sinsky. “There’s less capacity in the system to care for patients.”

Some could argue, then, that part-time physician work may contribute to physician shortage predictions. An Association of American Medical Colleges report estimates there will be a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 physicians by 2034.