User login

Cat Scratch Disease Presenting With Concurrent Pityriasis Rosea in a 10-Year-Old Girl

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

To the Editor:

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is caused by Bartonella henselae and Bartonella clarridgeiae bacteria transferred from cats to humans that results in an inflamed inoculation site and tender lymphadenopathy. Pityriasis rosea (PR) and PR-like eruptions are self-limited, acute exanthems that have been associated with infections, vaccinations, and medications. We report a case of PR occurring in a 10-year-old girl with CSD, which may suggest an association between the 2 diseases.

A 10-year-old girl who was otherwise healthy presented in the winter with a rash of 5 days’ duration. Fourteen days prior to the rash, the patient reported being scratched by a new kitten and noted a pinpoint “puncture” on the left forearm that developed into a red papule over the following week. Seven days after the cat scratch, the patient experienced pain and swelling in the left axilla. Approximately 1 week after the onset of lymphadenopathy, the patient developed an asymptomatic rash that started with a large spot on the left chest, followed by smaller spots appearing over the next 2 days and spreading to the rest of the trunk. Four days after the rash onset, the patient experienced a mild headache, low-grade subjective fever, and chills. She denied any recent travel, bug bites, sore throat, and diarrhea. She was up-to-date on all vaccinations and had not received any vaccines preceding the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2-cm pink, scaly, thin plaque with a collarette of scale on the left upper chest (herald patch), along with multiple thin pink papules and small plaques with central scale on the trunk (Figure 1). A pustule with adjacent linear erosion was present on the left ventral forearm (Figure 2). The patient had a tender subcutaneous nodule in the left axilla as well as bilateral anterior and posterior cervical-chain subcutaneous tender nodules. There was no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucosae.

The patient was empirically treated for CSD with azithromycin (200 mg/5 mL), 404 mg on day 1 followed by 202 mg daily for 4 days. The rash was treated with hydrocortisone cream 2.5% twice daily for 2 weeks. A wound culture of the pustule on the left forearm was negative for neutrophils and organisms. Antibody serologies obtained 4 weeks after presentation were notable for an elevated B henselae IgG titer of 1:640, confirming the diagnosis of CSD. Following treatment with azithromycin and hydrocortisone, all of the patient’s symptoms resolved after 1 to 2 weeks.

Cat scratch disease is a zoonotic infection caused by the bacteria B henselae and the more recently described pathogen B clarridgeiae. Cat fleas spread these bacteria among cats, which subsequently inoculate the bacteria into humans through bites and scratches. The incidence of CSD in the United States is estimated to be 4.5 to 9.3 per 100,000 individuals in the outpatient setting and 0.19 to 0.86 per 100,000 individuals in the inpatient setting.1 Geographic variance can occur based on flea populations, resulting in higher incidence in warm humid climates and lower incidence in mountainous arid climates. The incidence of CSD in the pediatric population is highest in children aged 5 to 9 years. A national representative survey (N=3011) from 2017 revealed that 37.2% of primary care providers had diagnosed CSD in the prior year.1

Classic CSD presents as an erythematous papule at the inoculation site lasting days to weeks, with progression to tender lymphadenopathy lasting weeks to months. Fever, malaise, and chills also can be seen. Atypical CSD occurs in up to 24% of cases in immunocompetent patients.1 Atypical and systemic presentations are varied and can include fever of unknown origin, neuroretinitis, uveitis, retinal vessel occlusion, encephalitis, hepatosplenic lesions, Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, osteomyelitis, and endocarditis.1,2 Atypical dermatologic presentations of CSD include maculopapular rash in 7% of cases and erythema nodosum in 2.5% of cases, as well as rare reports of cutaneous vasculitis, urticaria, immune thrombocytopenic purpura, and papuloedematous eruption.3 Treatment guidelines for CSD vary widely depending on the clinical presentation as well as the immunocompetence of the infected individual. Our patient had limited regional lymphadenopathy with no signs of dissemination or neurologic involvement and was successfully treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin (weight based, 10 mg/kg). More extensive disease such as hepatosplenic or neurologic CSD may require multiple antibiotics for up to 6 weeks. Alternative or additional antibiotics used for CSD include rifampin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, gentamicin, and clarithromycin. Opinions vary as to whether all patients or just those with complicated infections warrant antibiotic therapy.4-6

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited acute exanthematous disease that is classically associated with a systemic reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. The incidence of PR is estimated to be 480 per 100,000 dermatologic patients. It is slightly more common in females and occurs most often in patients aged 10 to 35 years.7 Clinically, PR appears with the abrupt onset of a single erythematous scaly patch (termed the herald patch), followed by a secondary eruption of smaller erythematous scaly macules and patches along the trunk’s cleavage lines. The secondary eruption on the back is sometimes termed a Christmas or fir tree pattern.7,8

In addition to the classic presentation of PR, there have been reports of numerous atypical clinical presentations. The herald patch, which classically presents on the trunk, also has been reported to present on the extremities; PR of the extremities is defined by lesions that appear as large scaly plaques on the extremities only. Inverse PR presents with lesions occurring in flexural areas and acral surfaces but not on the trunk. There also is an acral PR variant in which lesions appear only on the palms, wrists, and soles. Purpuric or hemorrhagic PR has been described and presents with purpura and petechiae with or without collarettes of scale in diffuse locations, including the palate. Oral PR presents more commonly in patients of color as erosions, ulcers, hemorrhagic lesions, bullae, or geographic tongue. Erythema multiforme–like PR appears with targetoid lesions on the trunk, face, neck, and arms without a history of herpes simplex virus infection. A large pear-shaped herald patch has been reported and characterizes the gigantea PR of Darier variant. Irritated PR occurs with typical PR findings, but afflicted patients report severe pain and burning with diaphoresis. Relapsing PR can occur within 1 year of a prior episode of PR and presents without a herald patch. Persistent PR is defined by PR lasting more than 3 months, and most reported cases have included oral lesions. Finally, other PR variants that have been described include urticarial, papular, follicular, vesicular, and hypopigmented types.7-9

Furthermore, there have been reports of multiple atypical presentations occurring simultaneously in the same patient.10 Although PR classically has been associated with HHV-6 and/or HHV-7 reactivation, it has been reported with a few other clinical situations and conditions. Pityriasislike eruption specifically refers to an exanthem secondary to drugs or vaccination that resembles PR but shows clinical differences, including diffuse and confluent dusky-red macules and/or plaques with or without desquamation on the trunk, extremities, and face. Drugs that have been implicated as triggers include ACE inhibitors, gold, isotretinoin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, omeprazole, terbinafine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Smallpox, tuberculosis, poliomyelitis, influenza, diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, pneumococcus, papillomavirus, yellow fever, and pertussis vaccinations also have been associated with PR.7,11,12 Additionally, PR has been reported to occur with active systemic infections, specifically H1N1 influenza, though it is rare.13 Because of its self-limited course, treatment of PR most often involves only reassurance. Topical corticosteroids may be appropriate for pruritus.7,8

Pediatric health care providers including dermatologists should be familiar with both CSD and PR because they are common diseases that more often are encountered in the pediatric population. We present a unique case of CSD presenting with concurrent PR, which highlights a potential new etiology for PR and a rare cutaneous manifestation of CSD. Further investigation into a possible relationship between CSD and PR may be warranted. Patients with any signs and symptoms of fever, tender lymphadenopathy, worsening rash, or exposure to cats warrant a thorough history and physical examination to ensure that neither entity is overlooked.

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

- Nelson CA, Moore AR, Perea AE, et al. Cat scratch disease: U.S. clinicians’ experience and knowledge [published online July 14, 2017]. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:67-73. doi:10.1111/zph.12368

- Habot-Wilner Z, Trivizki O, Goldstein M, et al. Cat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and treatment outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:E524-E532. doi:10.1111/aos.13684

- Schattner A, Uliel L, Dubin I. The cat did it: erythema nodosum and additional atypical presentations of Bartonella henselae infection in immunocompetent hosts [published online February 16, 2018]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222511

- Shorbatli L, Koranyi K, Nahata M. Effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in pediatric patients with cat scratch disease. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1458-1461. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0746-1

- Bass JW, Freitas BC, Freitas AD, et al. Prospective randomized double blind placebo-controlled evaluation of azithromycin for treatment of cat-scratch disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:447-452. doi:10.1097/00006454-199806000-00002

- Spach DH, Kaplan SL. Treatment of cat scratch disease. UpToDate. Updated December 9, 2021. Accessed September 12, 2023. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-cat-scratch-disease

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Rebora A, et al. Pityriasis rosea: a comprehensive classification. Dermatology. 2016;232:431-437. doi:10.1159/000445375

- Urbina F, Das A, Sudy E. Clinical variants of pityriasis rosea. World J Clin Cases. 2017;5:203-211. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.203

- Alzahrani NA, Al Jasser MI. Geographic tonguelike presentation in a child with pityriasis rosea: case report and review of oral manifestations of pityriasis rosea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E124-E127. doi:10.1111/pde.13417

- Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg V. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: a case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538-540. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: how to distinguish them? JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:800-801. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.04.002

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Javor S, et al. Vaccine-induced pityriasis rosea and pityriasis rosea-like eruptions: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:544-545. doi:10.1111/jdv.12942

- Mubki TF, Bin Dayel SA, Kadry R. A case of pityriasis rosea concurrent with the novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:341-342. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01090.x

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should familiarize themselves with the physical examination findings of cat scratch disease.

- There are numerous clinical variants and triggers of pityriasis rosea (PR).

- There may be a new infectious trigger for PR, and exposure to cats prior to a classic PR eruption should raise one’s suspicion as a possible cause.

Primary care clinicians should spearhead HIV prevention

HIV continues to be a significant public health concern in the United States, with an estimated 1.2 million people currently living with the virus and more than 30,000 new diagnoses in 2020 alone.

Primary care clinicians can help decrease rates of HIV infection by prescribing pre-exposure prophylaxis to people who are sexually active.

But many do not.

“In medical school, we don’t spend much time discussing sexuality, sexual behavior, sexually transmitted infections, and such, so providers may feel uncomfortable asking what kind of sex their patient is having and with whom, whether they use a condom, and other basics,” said Matthew M. Hamill, MBChB, PhD, MPH, a specialist in sexually transmitted diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) is an antiviral medication that cuts the risk of contracting HIV through sex by around 99% when taken as prescribed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Many people who would benefit from PrEP are not receiving this highly effective medication,” said John B. Wong, MD, a primary care internist and professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston. The gap is particularly acute among Black, Hispanic, and Latino people, who are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with HIV but are much less likely than Whites to receive PrEP, he said.

Dr. Wong, a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, helped write the group’s new PrEP recommendations. Published in August, the guidelines call for clinicians to prescribe the drugs to adolescents and adults who do not have HIV but are at an increased risk for infection.

“Primary care physicians are ideally positioned to prescribe PrEP for their patients because they have longitudinal relationships: They get to know their patients, and hopefully their patients feel comfortable talking with them about their sexual health,” said Brandon Pollak, MD, a primary care physician and HIV specialist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus.

Dr. Pollak, who was not involved with the USPSTF recommendations, cares for patients who are heterosexual and living with HIV.

Clinicians should consider PrEP for all patients who have sex with someone who has HIV, do not use condoms, or have had a sexually transmitted infection within the previous 6 months. Men who have sex with men, transgender women who have sex with men, people who inject illicit drugs or engage in transactional sex, and Black, Hispanic, and Latino individuals also are at increased risk for the infection.

“The vast majority of patients on PrEP in any form sail through with no problems; they have regular lab work and can follow up in person or by telemedicine,” Dr. Hamill said. “They tend to be young, fit people without complicated medical histories, and the medications are very well-tolerated, particularly if people expect some short-term side effects.”

What you need to know when prescribing PrEP

Prescribing PrEP is similar in complexity to prescribing hypertension or diabetes medications, Dr. Hamill said.

Because taking the medications while already infected with the virus can lead to the emergence of drug-resistant HIV, patients must have a negative HIV test before starting PrEP. In addition, the USPSTF recommends testing for other sexually transmitted infections and for pregnancy, if appropriate. The task force also recommends conducting kidney function and hepatitis B tests, and a lipid profile before starting specific types of PrEP.

HIV screening is also recommended at 3-month intervals.

“Providers may order labs done at 3- to 4-month intervals but only see patients in clinic once or twice per year, depending on patient needs and risk behaviors,” said Jill S. Blumenthal, MD, associate professor of medicine at UC San Diego Health.

Clinicians should consider medication adherence and whether a patient is likely to take a pill once a day or could benefit from receiving an injection every 2 months. Patients may experience side effects such as diarrhea or headache with oral PrEP or soreness at the injection site. In rare cases, some of the drugs may cause kidney toxicity or bone mineral loss, according to Dr. Hamill.

Three similarly effective forms of PrEP approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration enable clinicians to tailor the medications to the specific needs and preferences of each patient. Truvada (emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) and Descovy (emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide) are both daily tablets, although the latter is not advised for people assigned female sex at birth who have receptive vaginal sex. Apretude (cabotegravir), an injectable agent, is not recommended for people who inject illegal drugs.

Patients with renal or bone disease are not good candidates for Truvada.

“Truvada can decrease bone density, so for someone with osteoporosis, you might choose Descovy or Apretude,” Dr. Pollak said. “For someone with chronic kidney disease, consider Descovy or Apretude. “If a patient has hepatitis B, Truvada or Descovy are appropriate, because hepatitis B is treatable.”

Patients taking an injectable PrEP may need more attention, because the concentration of the medication in the body decreases slowly and may linger for many months at low levels that don’t prevent HIV, according to Dr. Hamill. Someone who acquires HIV during that “tail” period might develop resistance to PrEP.

New research also showed that Descovy users were at elevated risk of developing hypertension and statin initiation, especially among those over age 40 years.

Primary care physicians may want to consult with renal specialists about medication safety in patients with severe kidney disease or with rheumatologists or endocrinologists about metabolic bone disease concerns, Dr. Hamill said.

Meanwhile, if a person begins a monogamous relationship and their risk for HIV drops, “it’s fine to stop taking PrEP tablets,” Dr. Pollak said. “I would still recommend routine HIV screening every 6 or 12 months or however often, depending on other risk factors.”

Caring for these patients entails ensuring labs are completed, monitoring adherence, ordering refills, and scheduling regular follow-up visits.

“For the vast majority of patients, the primary care physician is perfectly equipped for their care through the entire PrEP journey, from discussion and initiation to provision of PrEP,” and most cases do not require specialist care, Dr. Hamill said.

However, “if PrEP fails, which is exceedingly rare, primary care physicians should refer patients immediately, preferably with a warm handoff, for linkage to HIV care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

Talking about PrEP opens the door to conversations with patients about sexual health and broader health issues, Dr. Hamill said. Although these may not come naturally to primary care clinicians, training is available. The National Network of STD Clinical Prevention Training Centers, funded by the CDC, trains providers on how to overcome their anxiety and have open, inclusive conversations about sexuality and sexual behaviors with transgender and gender-diverse, nonbinary people.

“People worry about saying the wrong thing, about causing offense,” Dr. Hamill said. “But once you get comfortable discussing sexuality, you may open conversations around other health issues.”

Barriers for patients

The task force identified several barriers to PrEP access for patients because of lack of trusting relationships with health care, the effects of structural racism on health disparities, and persistent biases within the health care system.

Racial and ethnic disparities in HIV incidence persist, with 42% of new diagnoses occurring among Black people, 27% among Hispanic or Latino people, and 26% among White people in 2020.

Rates of PrEP usage for a year or longer are also low. Sometimes the patient no longer needs PrEP, but barriers often involve the costs of taking time off from work and arranging transportation to clinic visits.

Although nearly all insurance plans and state Medicaid programs cover PrEP, if a patient does not have coverage, the drugs and required tests and office visits can be expensive.

“One of the biggest barriers for all providers is navigating our complicated health system and drug assistance programs,” said Mehri S. McKellar, MD, associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C.

But lower-cost FDA-approved generic emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is now available, and clinicians can direct patients to programs that help provide the medications at low or no cost.

“Providing PrEP care is straightforward, beneficial, and satisfying,” Dr. Hamill said. “You help people protect themselves from a life-changing diagnosis, and the health system doesn’t need to pay the cost of treating HIV. Everyone wins.”

Dr. Hamill, Dr. McKellar, Dr. Pollak, and Dr. Wong have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Blumenthal has reported a financial relationship with Gilead Sciences.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

HIV continues to be a significant public health concern in the United States, with an estimated 1.2 million people currently living with the virus and more than 30,000 new diagnoses in 2020 alone.

Primary care clinicians can help decrease rates of HIV infection by prescribing pre-exposure prophylaxis to people who are sexually active.

But many do not.

“In medical school, we don’t spend much time discussing sexuality, sexual behavior, sexually transmitted infections, and such, so providers may feel uncomfortable asking what kind of sex their patient is having and with whom, whether they use a condom, and other basics,” said Matthew M. Hamill, MBChB, PhD, MPH, a specialist in sexually transmitted diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) is an antiviral medication that cuts the risk of contracting HIV through sex by around 99% when taken as prescribed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Many people who would benefit from PrEP are not receiving this highly effective medication,” said John B. Wong, MD, a primary care internist and professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston. The gap is particularly acute among Black, Hispanic, and Latino people, who are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with HIV but are much less likely than Whites to receive PrEP, he said.

Dr. Wong, a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, helped write the group’s new PrEP recommendations. Published in August, the guidelines call for clinicians to prescribe the drugs to adolescents and adults who do not have HIV but are at an increased risk for infection.

“Primary care physicians are ideally positioned to prescribe PrEP for their patients because they have longitudinal relationships: They get to know their patients, and hopefully their patients feel comfortable talking with them about their sexual health,” said Brandon Pollak, MD, a primary care physician and HIV specialist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus.

Dr. Pollak, who was not involved with the USPSTF recommendations, cares for patients who are heterosexual and living with HIV.

Clinicians should consider PrEP for all patients who have sex with someone who has HIV, do not use condoms, or have had a sexually transmitted infection within the previous 6 months. Men who have sex with men, transgender women who have sex with men, people who inject illicit drugs or engage in transactional sex, and Black, Hispanic, and Latino individuals also are at increased risk for the infection.

“The vast majority of patients on PrEP in any form sail through with no problems; they have regular lab work and can follow up in person or by telemedicine,” Dr. Hamill said. “They tend to be young, fit people without complicated medical histories, and the medications are very well-tolerated, particularly if people expect some short-term side effects.”

What you need to know when prescribing PrEP

Prescribing PrEP is similar in complexity to prescribing hypertension or diabetes medications, Dr. Hamill said.

Because taking the medications while already infected with the virus can lead to the emergence of drug-resistant HIV, patients must have a negative HIV test before starting PrEP. In addition, the USPSTF recommends testing for other sexually transmitted infections and for pregnancy, if appropriate. The task force also recommends conducting kidney function and hepatitis B tests, and a lipid profile before starting specific types of PrEP.

HIV screening is also recommended at 3-month intervals.

“Providers may order labs done at 3- to 4-month intervals but only see patients in clinic once or twice per year, depending on patient needs and risk behaviors,” said Jill S. Blumenthal, MD, associate professor of medicine at UC San Diego Health.

Clinicians should consider medication adherence and whether a patient is likely to take a pill once a day or could benefit from receiving an injection every 2 months. Patients may experience side effects such as diarrhea or headache with oral PrEP or soreness at the injection site. In rare cases, some of the drugs may cause kidney toxicity or bone mineral loss, according to Dr. Hamill.

Three similarly effective forms of PrEP approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration enable clinicians to tailor the medications to the specific needs and preferences of each patient. Truvada (emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) and Descovy (emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide) are both daily tablets, although the latter is not advised for people assigned female sex at birth who have receptive vaginal sex. Apretude (cabotegravir), an injectable agent, is not recommended for people who inject illegal drugs.

Patients with renal or bone disease are not good candidates for Truvada.

“Truvada can decrease bone density, so for someone with osteoporosis, you might choose Descovy or Apretude,” Dr. Pollak said. “For someone with chronic kidney disease, consider Descovy or Apretude. “If a patient has hepatitis B, Truvada or Descovy are appropriate, because hepatitis B is treatable.”

Patients taking an injectable PrEP may need more attention, because the concentration of the medication in the body decreases slowly and may linger for many months at low levels that don’t prevent HIV, according to Dr. Hamill. Someone who acquires HIV during that “tail” period might develop resistance to PrEP.

New research also showed that Descovy users were at elevated risk of developing hypertension and statin initiation, especially among those over age 40 years.

Primary care physicians may want to consult with renal specialists about medication safety in patients with severe kidney disease or with rheumatologists or endocrinologists about metabolic bone disease concerns, Dr. Hamill said.

Meanwhile, if a person begins a monogamous relationship and their risk for HIV drops, “it’s fine to stop taking PrEP tablets,” Dr. Pollak said. “I would still recommend routine HIV screening every 6 or 12 months or however often, depending on other risk factors.”

Caring for these patients entails ensuring labs are completed, monitoring adherence, ordering refills, and scheduling regular follow-up visits.

“For the vast majority of patients, the primary care physician is perfectly equipped for their care through the entire PrEP journey, from discussion and initiation to provision of PrEP,” and most cases do not require specialist care, Dr. Hamill said.

However, “if PrEP fails, which is exceedingly rare, primary care physicians should refer patients immediately, preferably with a warm handoff, for linkage to HIV care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

Talking about PrEP opens the door to conversations with patients about sexual health and broader health issues, Dr. Hamill said. Although these may not come naturally to primary care clinicians, training is available. The National Network of STD Clinical Prevention Training Centers, funded by the CDC, trains providers on how to overcome their anxiety and have open, inclusive conversations about sexuality and sexual behaviors with transgender and gender-diverse, nonbinary people.

“People worry about saying the wrong thing, about causing offense,” Dr. Hamill said. “But once you get comfortable discussing sexuality, you may open conversations around other health issues.”

Barriers for patients

The task force identified several barriers to PrEP access for patients because of lack of trusting relationships with health care, the effects of structural racism on health disparities, and persistent biases within the health care system.

Racial and ethnic disparities in HIV incidence persist, with 42% of new diagnoses occurring among Black people, 27% among Hispanic or Latino people, and 26% among White people in 2020.

Rates of PrEP usage for a year or longer are also low. Sometimes the patient no longer needs PrEP, but barriers often involve the costs of taking time off from work and arranging transportation to clinic visits.

Although nearly all insurance plans and state Medicaid programs cover PrEP, if a patient does not have coverage, the drugs and required tests and office visits can be expensive.

“One of the biggest barriers for all providers is navigating our complicated health system and drug assistance programs,” said Mehri S. McKellar, MD, associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C.

But lower-cost FDA-approved generic emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is now available, and clinicians can direct patients to programs that help provide the medications at low or no cost.

“Providing PrEP care is straightforward, beneficial, and satisfying,” Dr. Hamill said. “You help people protect themselves from a life-changing diagnosis, and the health system doesn’t need to pay the cost of treating HIV. Everyone wins.”

Dr. Hamill, Dr. McKellar, Dr. Pollak, and Dr. Wong have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Blumenthal has reported a financial relationship with Gilead Sciences.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

HIV continues to be a significant public health concern in the United States, with an estimated 1.2 million people currently living with the virus and more than 30,000 new diagnoses in 2020 alone.

Primary care clinicians can help decrease rates of HIV infection by prescribing pre-exposure prophylaxis to people who are sexually active.

But many do not.

“In medical school, we don’t spend much time discussing sexuality, sexual behavior, sexually transmitted infections, and such, so providers may feel uncomfortable asking what kind of sex their patient is having and with whom, whether they use a condom, and other basics,” said Matthew M. Hamill, MBChB, PhD, MPH, a specialist in sexually transmitted diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine, Baltimore.

PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) is an antiviral medication that cuts the risk of contracting HIV through sex by around 99% when taken as prescribed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Many people who would benefit from PrEP are not receiving this highly effective medication,” said John B. Wong, MD, a primary care internist and professor of medicine at Tufts University, Boston. The gap is particularly acute among Black, Hispanic, and Latino people, who are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with HIV but are much less likely than Whites to receive PrEP, he said.

Dr. Wong, a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, helped write the group’s new PrEP recommendations. Published in August, the guidelines call for clinicians to prescribe the drugs to adolescents and adults who do not have HIV but are at an increased risk for infection.

“Primary care physicians are ideally positioned to prescribe PrEP for their patients because they have longitudinal relationships: They get to know their patients, and hopefully their patients feel comfortable talking with them about their sexual health,” said Brandon Pollak, MD, a primary care physician and HIV specialist at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus.

Dr. Pollak, who was not involved with the USPSTF recommendations, cares for patients who are heterosexual and living with HIV.

Clinicians should consider PrEP for all patients who have sex with someone who has HIV, do not use condoms, or have had a sexually transmitted infection within the previous 6 months. Men who have sex with men, transgender women who have sex with men, people who inject illicit drugs or engage in transactional sex, and Black, Hispanic, and Latino individuals also are at increased risk for the infection.

“The vast majority of patients on PrEP in any form sail through with no problems; they have regular lab work and can follow up in person or by telemedicine,” Dr. Hamill said. “They tend to be young, fit people without complicated medical histories, and the medications are very well-tolerated, particularly if people expect some short-term side effects.”

What you need to know when prescribing PrEP

Prescribing PrEP is similar in complexity to prescribing hypertension or diabetes medications, Dr. Hamill said.

Because taking the medications while already infected with the virus can lead to the emergence of drug-resistant HIV, patients must have a negative HIV test before starting PrEP. In addition, the USPSTF recommends testing for other sexually transmitted infections and for pregnancy, if appropriate. The task force also recommends conducting kidney function and hepatitis B tests, and a lipid profile before starting specific types of PrEP.

HIV screening is also recommended at 3-month intervals.

“Providers may order labs done at 3- to 4-month intervals but only see patients in clinic once or twice per year, depending on patient needs and risk behaviors,” said Jill S. Blumenthal, MD, associate professor of medicine at UC San Diego Health.

Clinicians should consider medication adherence and whether a patient is likely to take a pill once a day or could benefit from receiving an injection every 2 months. Patients may experience side effects such as diarrhea or headache with oral PrEP or soreness at the injection site. In rare cases, some of the drugs may cause kidney toxicity or bone mineral loss, according to Dr. Hamill.

Three similarly effective forms of PrEP approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration enable clinicians to tailor the medications to the specific needs and preferences of each patient. Truvada (emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) and Descovy (emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide) are both daily tablets, although the latter is not advised for people assigned female sex at birth who have receptive vaginal sex. Apretude (cabotegravir), an injectable agent, is not recommended for people who inject illegal drugs.

Patients with renal or bone disease are not good candidates for Truvada.

“Truvada can decrease bone density, so for someone with osteoporosis, you might choose Descovy or Apretude,” Dr. Pollak said. “For someone with chronic kidney disease, consider Descovy or Apretude. “If a patient has hepatitis B, Truvada or Descovy are appropriate, because hepatitis B is treatable.”

Patients taking an injectable PrEP may need more attention, because the concentration of the medication in the body decreases slowly and may linger for many months at low levels that don’t prevent HIV, according to Dr. Hamill. Someone who acquires HIV during that “tail” period might develop resistance to PrEP.

New research also showed that Descovy users were at elevated risk of developing hypertension and statin initiation, especially among those over age 40 years.

Primary care physicians may want to consult with renal specialists about medication safety in patients with severe kidney disease or with rheumatologists or endocrinologists about metabolic bone disease concerns, Dr. Hamill said.

Meanwhile, if a person begins a monogamous relationship and their risk for HIV drops, “it’s fine to stop taking PrEP tablets,” Dr. Pollak said. “I would still recommend routine HIV screening every 6 or 12 months or however often, depending on other risk factors.”

Caring for these patients entails ensuring labs are completed, monitoring adherence, ordering refills, and scheduling regular follow-up visits.

“For the vast majority of patients, the primary care physician is perfectly equipped for their care through the entire PrEP journey, from discussion and initiation to provision of PrEP,” and most cases do not require specialist care, Dr. Hamill said.

However, “if PrEP fails, which is exceedingly rare, primary care physicians should refer patients immediately, preferably with a warm handoff, for linkage to HIV care,” Dr. Blumenthal said.

Talking about PrEP opens the door to conversations with patients about sexual health and broader health issues, Dr. Hamill said. Although these may not come naturally to primary care clinicians, training is available. The National Network of STD Clinical Prevention Training Centers, funded by the CDC, trains providers on how to overcome their anxiety and have open, inclusive conversations about sexuality and sexual behaviors with transgender and gender-diverse, nonbinary people.

“People worry about saying the wrong thing, about causing offense,” Dr. Hamill said. “But once you get comfortable discussing sexuality, you may open conversations around other health issues.”

Barriers for patients

The task force identified several barriers to PrEP access for patients because of lack of trusting relationships with health care, the effects of structural racism on health disparities, and persistent biases within the health care system.

Racial and ethnic disparities in HIV incidence persist, with 42% of new diagnoses occurring among Black people, 27% among Hispanic or Latino people, and 26% among White people in 2020.

Rates of PrEP usage for a year or longer are also low. Sometimes the patient no longer needs PrEP, but barriers often involve the costs of taking time off from work and arranging transportation to clinic visits.

Although nearly all insurance plans and state Medicaid programs cover PrEP, if a patient does not have coverage, the drugs and required tests and office visits can be expensive.

“One of the biggest barriers for all providers is navigating our complicated health system and drug assistance programs,” said Mehri S. McKellar, MD, associate professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C.

But lower-cost FDA-approved generic emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is now available, and clinicians can direct patients to programs that help provide the medications at low or no cost.

“Providing PrEP care is straightforward, beneficial, and satisfying,” Dr. Hamill said. “You help people protect themselves from a life-changing diagnosis, and the health system doesn’t need to pay the cost of treating HIV. Everyone wins.”

Dr. Hamill, Dr. McKellar, Dr. Pollak, and Dr. Wong have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Blumenthal has reported a financial relationship with Gilead Sciences.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Diffuse Pruritic Eruption in an Immunocompromised Patient

The Diagnosis: Scabies Infestation

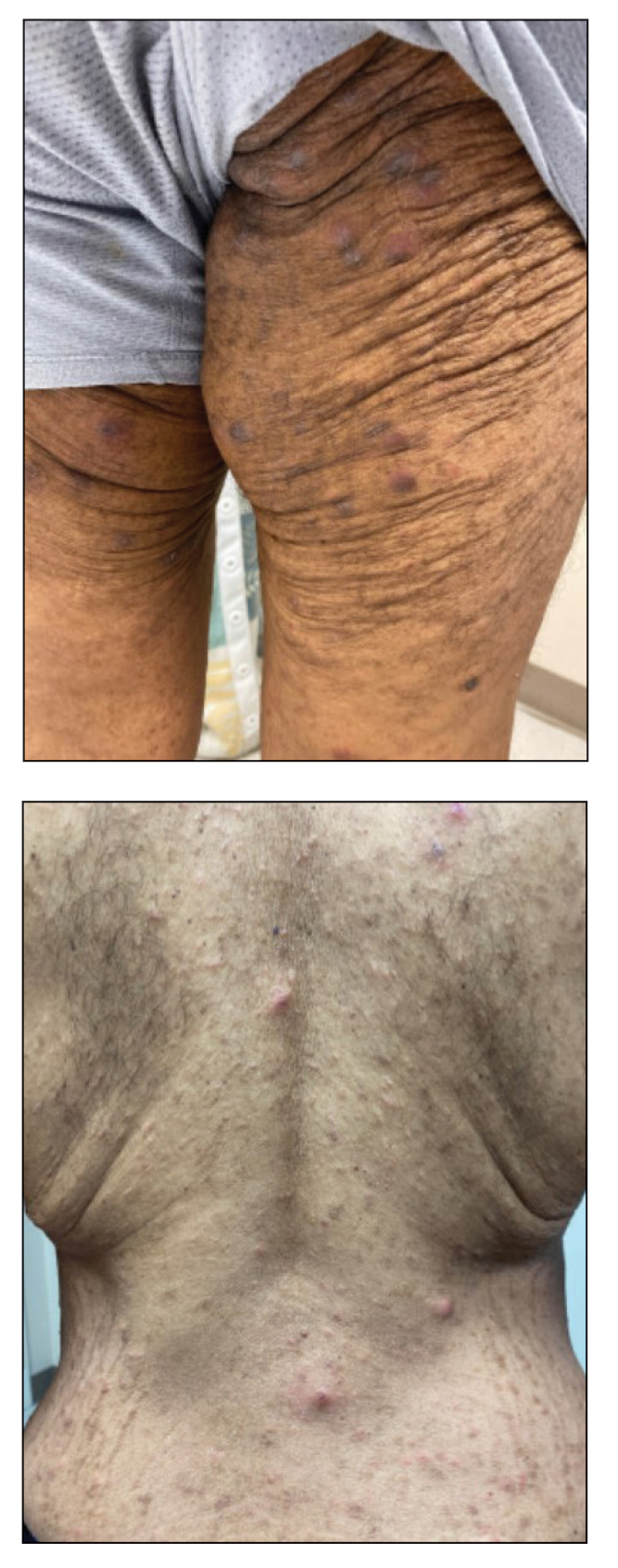

Direct microscopy revealed the presence of a live scabies mite and numerous eggs (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of a scabies infestation. Scabies, caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mite, characteristically presents in adults as pruritic hyperkeratotic plaques of the interdigital web spaces of the hands, flexor surfaces of the wrists and elbows, axillae, male genitalia, and breasts; however, an atypical presentation is common in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, such as our patient. In children, the palms, soles, and head (ie, face, scalp, neck) are common sites of involvement. Although dermatologists generally are familiar with severe atypical presentations such as Norwegian crusted scabies or bullous scabies, it is important that they are aware of other atypical presentations, such as the diffuse papulonodular variant observed in our patient.1 As such, a low threshold of suspicion for scabies infestations should be employed in immunocompromised patients with new-onset pruritic eruptions.

Direct microscopy is widely accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of scabies infestations; it is a fast and low-cost diagnostic tool. However, this technique displays variable sensitivity in clinical practice, requiring experience and a skilled hand.1,2 Other more sensitive diagnostic options for suspected scabies infestations include histopathology, serology, and molecular-based techniques such as DNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction. Although these tests do demonstrate greater sensitivity, they also are more invasive, time intensive, and costly.2 Therefore, they typically are not the first choice for a suspected scabies infestation. Dermoscopy has emerged as another tool to aid in the diagnosis of a suspected scabies infestation, enabling visualization of scaly burrows, eggs, and live mites. Classically, findings resembling a delta wing with contrail are seen on dermoscopic examination. The delta wing represents the brown triangular structure of the pigmented scabies mite head and anterior legs; the contrail is the lighter linear structures streaming behind the scabies mite (similar to visible vapor streams occurring behind flying jets), representing the burrow of the mite.

Although treatment of scabies infestations typically can be accomplished with permethrin cream 5%, the diffuse nature of our patient’s lesions in combination with his immunocompromised state made oral therapy a more appropriate choice. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations, the patient received 2 doses of oral weight-based ivermectin (200 μg/kg per dose) administered 1 week apart.1,3 The initial dose at day 1 serves to eliminate any scabies mites that are present, while the second dose 1 week later eliminates any residual eggs. Our patient experienced complete resolution of the symptoms following this treatment regimen.

It was important to differentiate our patient’s scabies infestation from other intensely pruritic conditions and morphologic mimics including papular urticaria, lichenoid drug eruptions, tinea corporis, and prurigo nodularis. Papular urticaria is an intensely pruritic hypersensitivity reaction to insect bites that commonly affects the extremities or other exposed areas. Visible puncta may be present.4 Our patient’s lesion distribution involved areas covered by clothing, no puncta were present, and he had no history of a recent arthropod assault, making the diagnosis of papular urticaria less likely.

Lichenoid drug eruptions classically present with symmetric, diffuse, pruritic, violaceous, scaling papules and plaques that present 2 to 3 months after exposure to an offending agent.5 Our patient’s eruption was papulonodular with no violaceous plaques, and he did not report changes to his medications, making a lichenoid drug eruption less likely.

Tinea corporis is another intensely pruritic condition that should be considered, especially in immunocompromised patients. It is caused by dermatophytes and classically presents as erythematous pruritic plaques with an annular, advancing, scaling border.6 Although immunocompromised patients may display extensive involvement, our patient’s lesions were papulonodular with no annular morphology or scale, rendering tinea corporis less likely.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition characterized by pruritic, violaceous, dome-shaped, smooth or crusted nodules secondary to repeated scratching or pressure. Although prurigo nodules can develop as a secondary change due to chronic excoriations in scabies infestations, prurigo nodules usually do not develop in areas such as the midline of the back that are not easily reached by the fingernails,7 which made prurigo nodularis less likely in our patient.

This case describes a unique papulonodular variant of scabies presenting in an immunocompromised cancer patient. Timely recognition and diagnosis of atypical scabies infestations can decrease morbidity and improve the quality of life of these patients.

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Siddig EE, Hay R. Laboratory-based diagnosis of scabies: a review of the current status. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116:4-9. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trab049

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites—scabies. medications. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ scabies/health_professionals/meds.html

- Örnek S, Zuberbier T, Kocatürk E. Annular urticarial lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:480-504. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol .2021.12.010

- Cheraghlou S, Levy LL. Fixed drug eruptions, bullous drug eruptions, and lichenoid drug eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:679-692. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.06.010

- Leung AK, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Tinea corporis: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2020;9:2020-5-6. doi:10.7573/dic.2020-5-6

- Kwon CD, Khanna R, Williams KA, et al. Diagnostic workup and evaluation of patients with prurigo nodularis. Medicines (Basel). 2019;6:97. doi:10.3390/medicines6040097

The Diagnosis: Scabies Infestation

Direct microscopy revealed the presence of a live scabies mite and numerous eggs (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of a scabies infestation. Scabies, caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mite, characteristically presents in adults as pruritic hyperkeratotic plaques of the interdigital web spaces of the hands, flexor surfaces of the wrists and elbows, axillae, male genitalia, and breasts; however, an atypical presentation is common in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, such as our patient. In children, the palms, soles, and head (ie, face, scalp, neck) are common sites of involvement. Although dermatologists generally are familiar with severe atypical presentations such as Norwegian crusted scabies or bullous scabies, it is important that they are aware of other atypical presentations, such as the diffuse papulonodular variant observed in our patient.1 As such, a low threshold of suspicion for scabies infestations should be employed in immunocompromised patients with new-onset pruritic eruptions.

Direct microscopy is widely accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of scabies infestations; it is a fast and low-cost diagnostic tool. However, this technique displays variable sensitivity in clinical practice, requiring experience and a skilled hand.1,2 Other more sensitive diagnostic options for suspected scabies infestations include histopathology, serology, and molecular-based techniques such as DNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction. Although these tests do demonstrate greater sensitivity, they also are more invasive, time intensive, and costly.2 Therefore, they typically are not the first choice for a suspected scabies infestation. Dermoscopy has emerged as another tool to aid in the diagnosis of a suspected scabies infestation, enabling visualization of scaly burrows, eggs, and live mites. Classically, findings resembling a delta wing with contrail are seen on dermoscopic examination. The delta wing represents the brown triangular structure of the pigmented scabies mite head and anterior legs; the contrail is the lighter linear structures streaming behind the scabies mite (similar to visible vapor streams occurring behind flying jets), representing the burrow of the mite.

Although treatment of scabies infestations typically can be accomplished with permethrin cream 5%, the diffuse nature of our patient’s lesions in combination with his immunocompromised state made oral therapy a more appropriate choice. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations, the patient received 2 doses of oral weight-based ivermectin (200 μg/kg per dose) administered 1 week apart.1,3 The initial dose at day 1 serves to eliminate any scabies mites that are present, while the second dose 1 week later eliminates any residual eggs. Our patient experienced complete resolution of the symptoms following this treatment regimen.

It was important to differentiate our patient’s scabies infestation from other intensely pruritic conditions and morphologic mimics including papular urticaria, lichenoid drug eruptions, tinea corporis, and prurigo nodularis. Papular urticaria is an intensely pruritic hypersensitivity reaction to insect bites that commonly affects the extremities or other exposed areas. Visible puncta may be present.4 Our patient’s lesion distribution involved areas covered by clothing, no puncta were present, and he had no history of a recent arthropod assault, making the diagnosis of papular urticaria less likely.

Lichenoid drug eruptions classically present with symmetric, diffuse, pruritic, violaceous, scaling papules and plaques that present 2 to 3 months after exposure to an offending agent.5 Our patient’s eruption was papulonodular with no violaceous plaques, and he did not report changes to his medications, making a lichenoid drug eruption less likely.

Tinea corporis is another intensely pruritic condition that should be considered, especially in immunocompromised patients. It is caused by dermatophytes and classically presents as erythematous pruritic plaques with an annular, advancing, scaling border.6 Although immunocompromised patients may display extensive involvement, our patient’s lesions were papulonodular with no annular morphology or scale, rendering tinea corporis less likely.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition characterized by pruritic, violaceous, dome-shaped, smooth or crusted nodules secondary to repeated scratching or pressure. Although prurigo nodules can develop as a secondary change due to chronic excoriations in scabies infestations, prurigo nodules usually do not develop in areas such as the midline of the back that are not easily reached by the fingernails,7 which made prurigo nodularis less likely in our patient.

This case describes a unique papulonodular variant of scabies presenting in an immunocompromised cancer patient. Timely recognition and diagnosis of atypical scabies infestations can decrease morbidity and improve the quality of life of these patients.

The Diagnosis: Scabies Infestation

Direct microscopy revealed the presence of a live scabies mite and numerous eggs (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of a scabies infestation. Scabies, caused by the Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mite, characteristically presents in adults as pruritic hyperkeratotic plaques of the interdigital web spaces of the hands, flexor surfaces of the wrists and elbows, axillae, male genitalia, and breasts; however, an atypical presentation is common in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals, such as our patient. In children, the palms, soles, and head (ie, face, scalp, neck) are common sites of involvement. Although dermatologists generally are familiar with severe atypical presentations such as Norwegian crusted scabies or bullous scabies, it is important that they are aware of other atypical presentations, such as the diffuse papulonodular variant observed in our patient.1 As such, a low threshold of suspicion for scabies infestations should be employed in immunocompromised patients with new-onset pruritic eruptions.

Direct microscopy is widely accepted as the gold standard for the diagnosis of scabies infestations; it is a fast and low-cost diagnostic tool. However, this technique displays variable sensitivity in clinical practice, requiring experience and a skilled hand.1,2 Other more sensitive diagnostic options for suspected scabies infestations include histopathology, serology, and molecular-based techniques such as DNA isolation and polymerase chain reaction. Although these tests do demonstrate greater sensitivity, they also are more invasive, time intensive, and costly.2 Therefore, they typically are not the first choice for a suspected scabies infestation. Dermoscopy has emerged as another tool to aid in the diagnosis of a suspected scabies infestation, enabling visualization of scaly burrows, eggs, and live mites. Classically, findings resembling a delta wing with contrail are seen on dermoscopic examination. The delta wing represents the brown triangular structure of the pigmented scabies mite head and anterior legs; the contrail is the lighter linear structures streaming behind the scabies mite (similar to visible vapor streams occurring behind flying jets), representing the burrow of the mite.

Although treatment of scabies infestations typically can be accomplished with permethrin cream 5%, the diffuse nature of our patient’s lesions in combination with his immunocompromised state made oral therapy a more appropriate choice. Based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations, the patient received 2 doses of oral weight-based ivermectin (200 μg/kg per dose) administered 1 week apart.1,3 The initial dose at day 1 serves to eliminate any scabies mites that are present, while the second dose 1 week later eliminates any residual eggs. Our patient experienced complete resolution of the symptoms following this treatment regimen.

It was important to differentiate our patient’s scabies infestation from other intensely pruritic conditions and morphologic mimics including papular urticaria, lichenoid drug eruptions, tinea corporis, and prurigo nodularis. Papular urticaria is an intensely pruritic hypersensitivity reaction to insect bites that commonly affects the extremities or other exposed areas. Visible puncta may be present.4 Our patient’s lesion distribution involved areas covered by clothing, no puncta were present, and he had no history of a recent arthropod assault, making the diagnosis of papular urticaria less likely.

Lichenoid drug eruptions classically present with symmetric, diffuse, pruritic, violaceous, scaling papules and plaques that present 2 to 3 months after exposure to an offending agent.5 Our patient’s eruption was papulonodular with no violaceous plaques, and he did not report changes to his medications, making a lichenoid drug eruption less likely.

Tinea corporis is another intensely pruritic condition that should be considered, especially in immunocompromised patients. It is caused by dermatophytes and classically presents as erythematous pruritic plaques with an annular, advancing, scaling border.6 Although immunocompromised patients may display extensive involvement, our patient’s lesions were papulonodular with no annular morphology or scale, rendering tinea corporis less likely.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition characterized by pruritic, violaceous, dome-shaped, smooth or crusted nodules secondary to repeated scratching or pressure. Although prurigo nodules can develop as a secondary change due to chronic excoriations in scabies infestations, prurigo nodules usually do not develop in areas such as the midline of the back that are not easily reached by the fingernails,7 which made prurigo nodularis less likely in our patient.

This case describes a unique papulonodular variant of scabies presenting in an immunocompromised cancer patient. Timely recognition and diagnosis of atypical scabies infestations can decrease morbidity and improve the quality of life of these patients.

- Chandler DJ, Fuller LC. A review of scabies: an infestation more than skin deep. Dermatology. 2019;235:79-90. doi:10.1159/000495290

- Siddig EE, Hay R. Laboratory-based diagnosis of scabies: a review of the current status. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2022;116:4-9. doi:10.1093/trstmh/trab049

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites—scabies. medications. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/ scabies/health_professionals/meds.html