User login

Firm Mobile Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

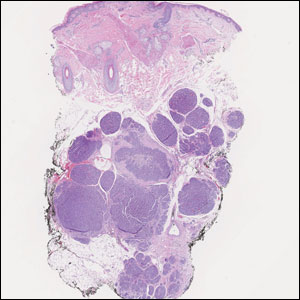

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

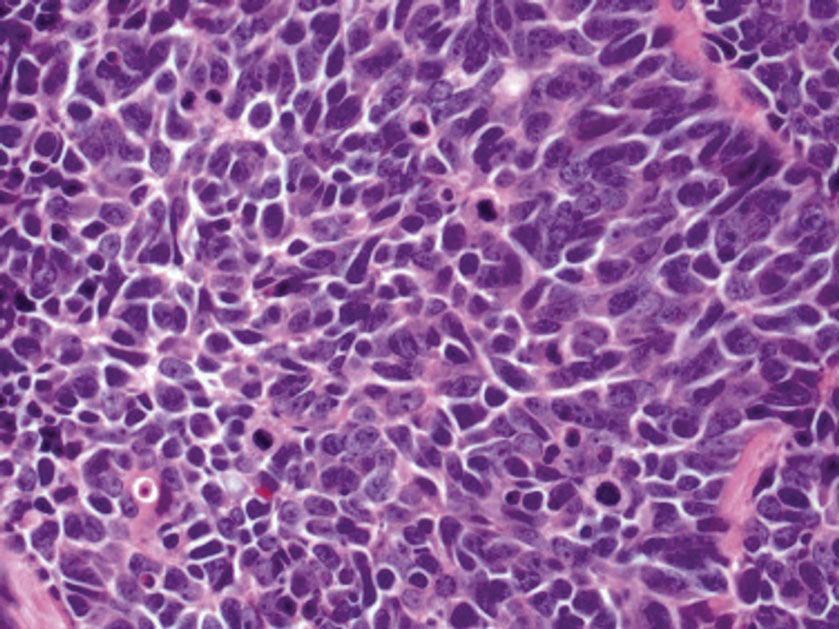

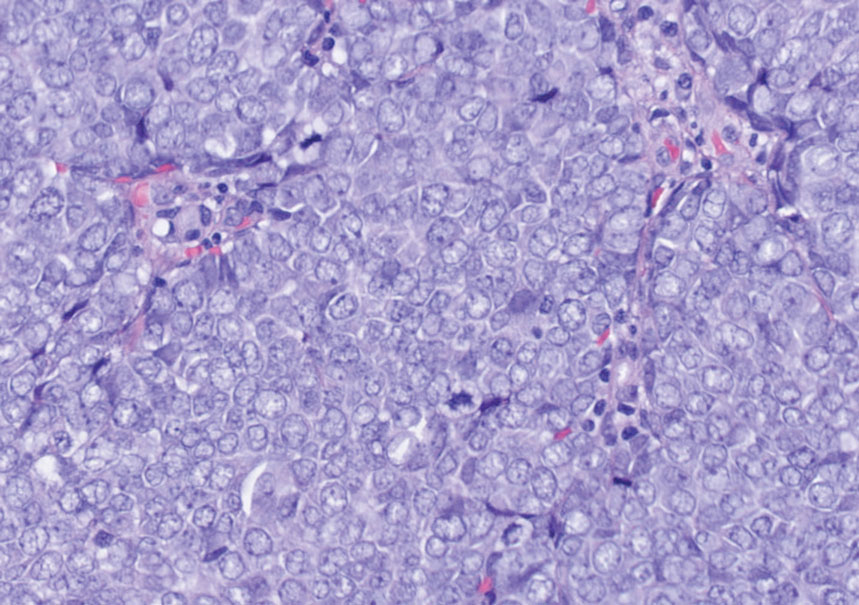

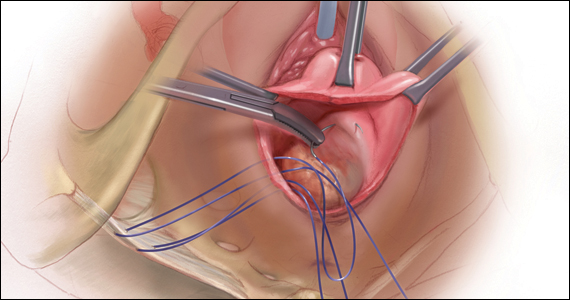

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

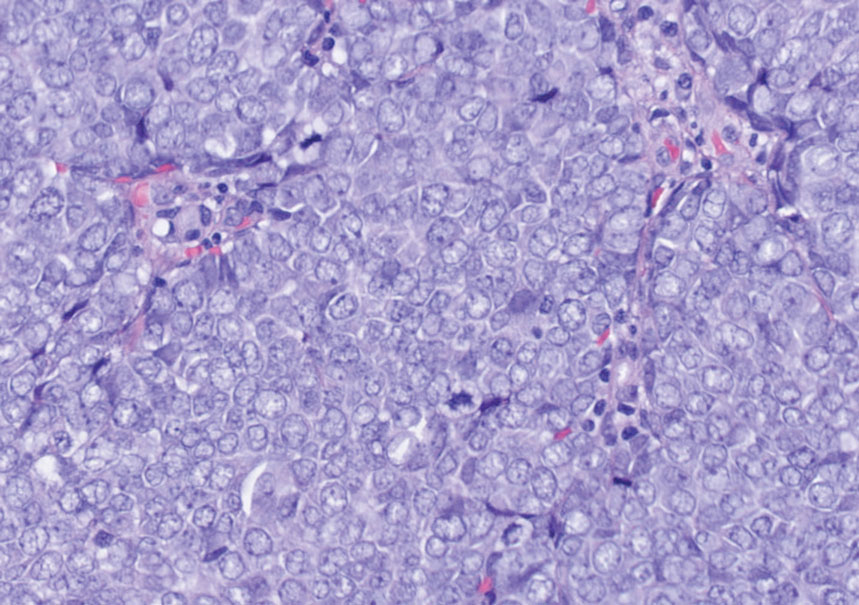

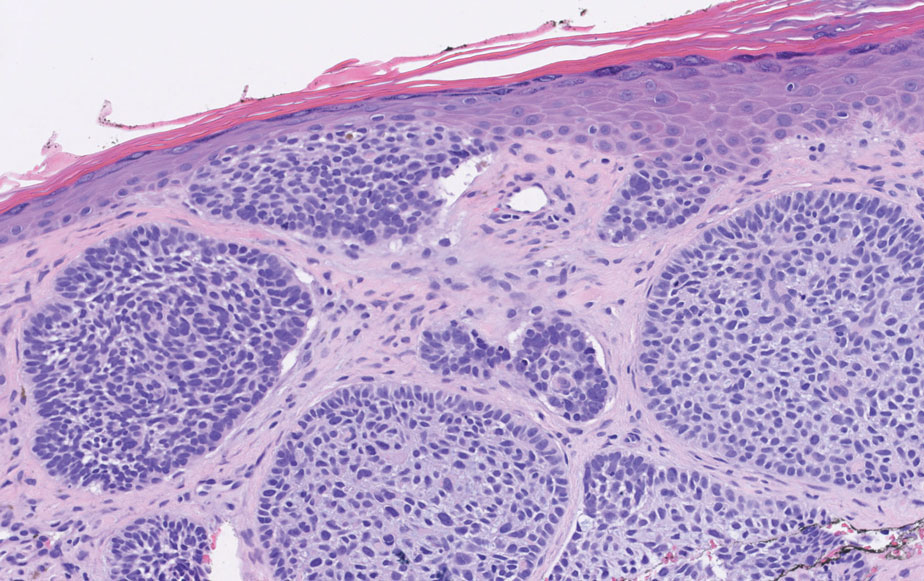

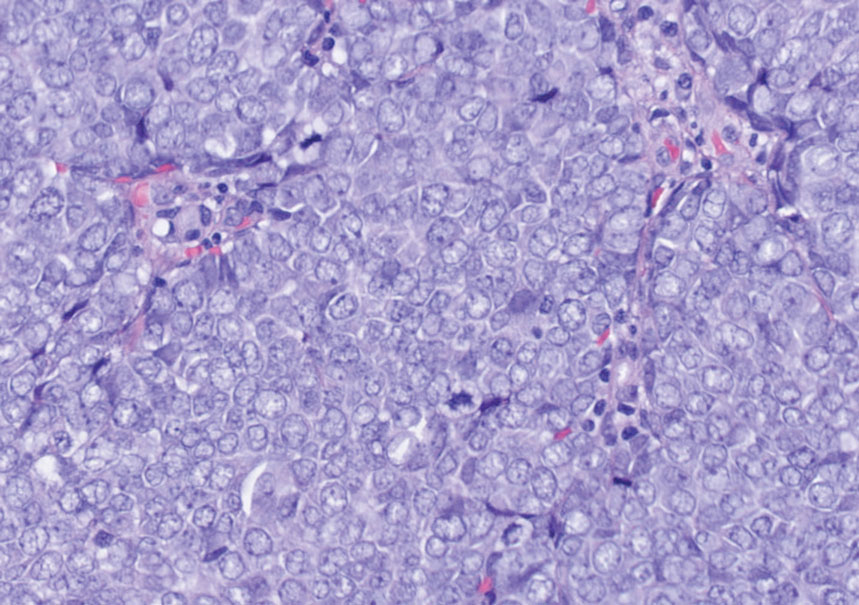

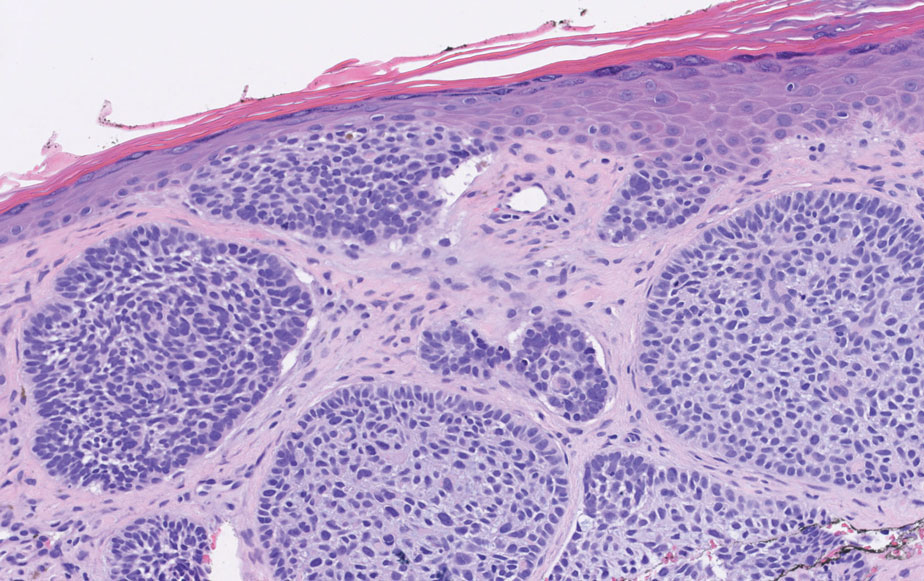

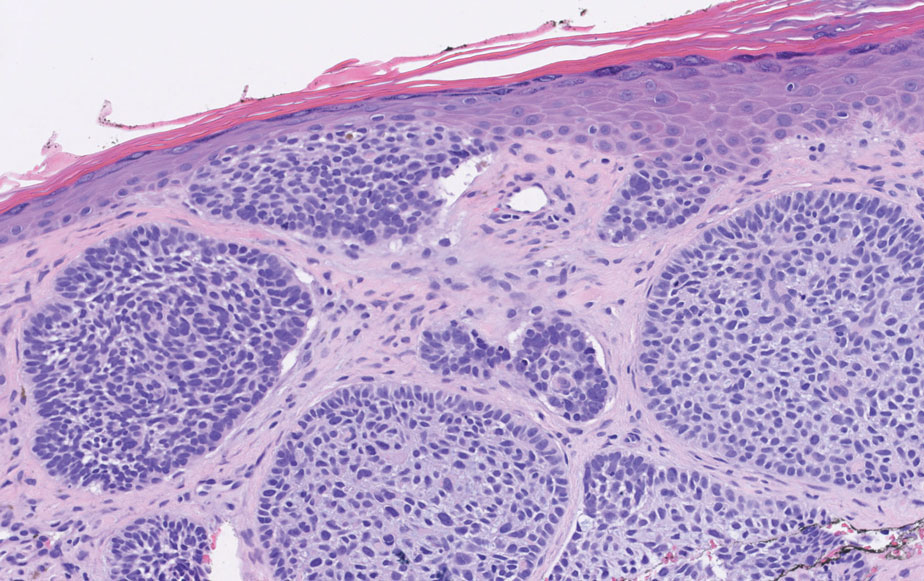

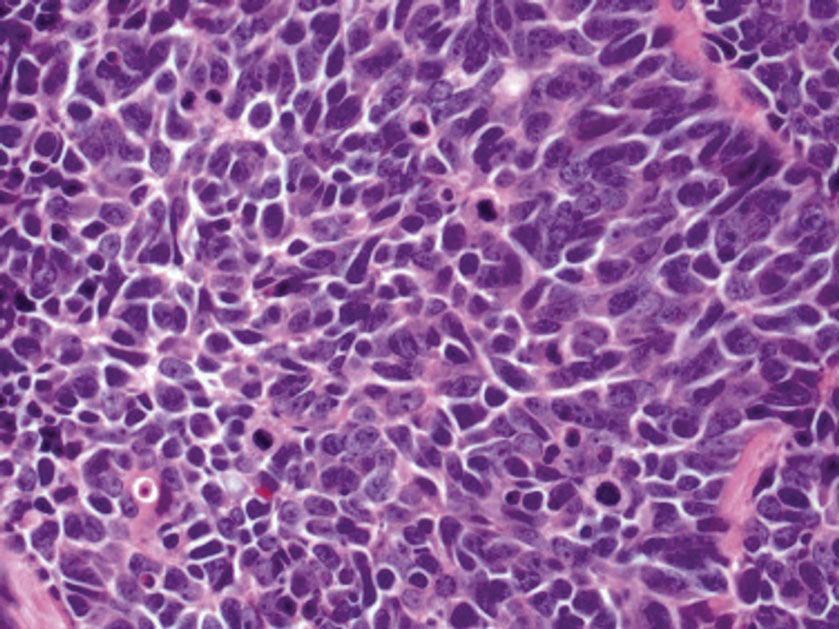

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

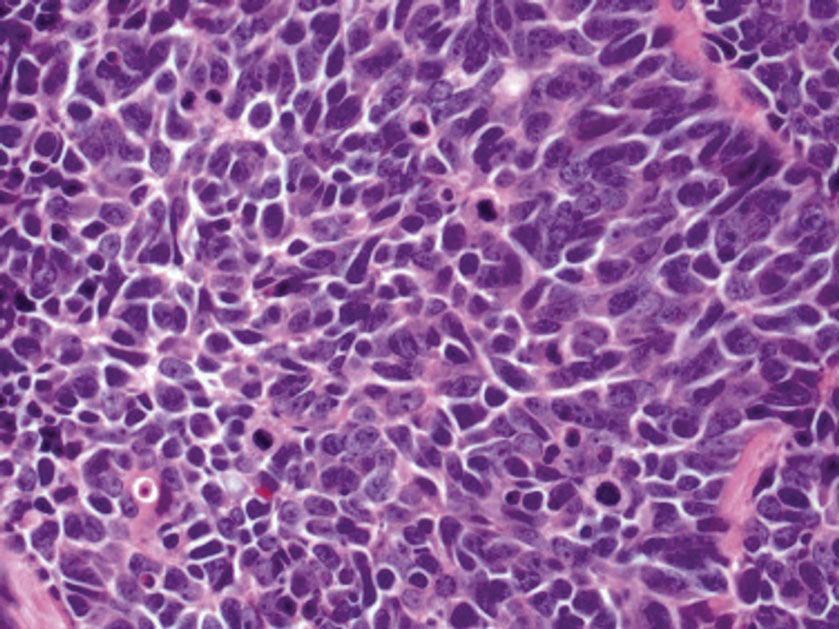

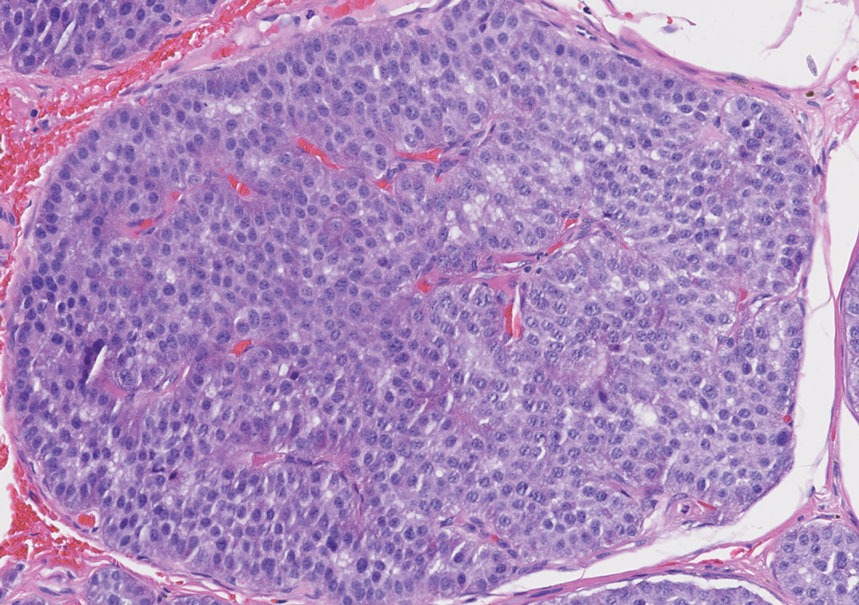

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor

Carcinoid tumors are derived from neuroendocrine cell compartments and generally arise in the gastrointestinal tract, with a quarter of carcinoids arising in the small bowel.1 Carcinoid tumors have an incidence of approximately 2 to 5 per 100,000 patients.2 Metastasis of carcinoids is approximately 31.2% to 46.7%.1 Metastasis to the skin is uncommon; we present a rare case of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum with metastasis to the scalp.

Unlike our patient, most patients with carcinoid tumors have an indolent clinical course. The most common cutaneous symptom is flushing, which occurs in 75% of patients.3 Secreted vasoactive peptides such as serotonin may cause other symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and bronchospasm; together, these symptoms comprise carcinoid syndrome. Carcinoid syndrome requires metastasis of the tumor to the liver or a site outside of the gastrointestinal tract because the liver will metabolize the secreted serotonin. However, even in patients with liver metastasis, carcinoid syndrome only occurs in approximately 10% of patients.4 Common skin findings of carcinoid syndrome include pellagralike dermatitis, flushing, and sclerodermalike changes.5 Our patient experienced several episodes of presyncope with symptoms of dyspnea, lightheadedness, and flushing but did not have bronchospasm or recurrent diarrhea. Intramuscular octreotide improved some symptoms.

The scalp accounts for approximately 15% of cutaneous metastases, the most common being from the lung, renal, and breast cancers.6 Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms metastatic AND [carcinoid OR neuroendocrine] tumors AND [skin OR cutaneous] revealed 47 cases.7-11 Similar to other skin metastases, cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors commonly present as firm erythematous nodules of varying sizes that may be asymptomatic, tender, or pruritic (Figure 1). Cases of carcinoid tumors with cutaneous metastasis as the initial and only presenting sign are exceedingly rare.12

Histology of carcinoid tumors reveals a dermal neoplasm composed of loosely cohesive, mildly atypical, polygonal cells with salt-and-pepper chromatin and eosinophilic cytoplasm, which are similar findings to the primary tumor. The cells may grow in the typical trabecular or organoid neuroendocrine pattern or exhibit a pseudoglandular growth pattern with prominent vessels (quiz image, top).12 Positive chromogranin and synaptophysin immunostaining are the most common and reliable markers used for the diagnosis of carcinoid tumors.

An important histopathologic differential diagnosis is the aggressive Merkel cell carcinoma, which also demonstrates homogenous salt-and-pepper chromatin but exhibits a higher mitotic rate and positive cytokeratin 20 staining (Figure 2).13 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) also may display similar features, including a blue tumor at scanning magnification and nodular or infiltrative growth patterns. The cell morphology of BCC is characterized by islands of basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm and frequent apoptosis, connecting to the epidermis with peripheral palisading, retraction artifact, and a myxoid stroma; BCC lacks the salt-and-pepper chromatin commonly seen in carcinoid tumors (Figure 3). Basal cell carcinoma is characterized by positive BerEP4 (epithelial cell adhesion molecule immunostain), cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin 14 uptake. Cytokeratin 20, often used to diagnose Merkel cell carcinoma, is negative in BCC. Chromogranin and synaptophysin occasionally may be positive in BCC.14

The superficial Ewing sarcoma family of tumors also may be included in the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors of the skin, but they are very rare. These tumors possess strong positive membranous staining of cytokeratin 99 and also can stain positively for synaptophysin and chromogranin.15 Epithelial membrane antigen, which is negative in Ewing sarcomas, is positive in carcinoid tumors.16 Neuroendocrine tumors of all sites share similar basic morphologic patterns, and multiple primary tumors should be considered, including small cell lung carcinoma (Figure 4).17,18 Red granulations and true glandular lumina typically are not seen in the lungs but are common in gastrointestinal carcinoids.18 Regarding immunohistochemistry, TTF-1 is negative and CDX2 is positive in gastroenteropancreatic carcinoids, suggesting that these 2 markers can help distinguish carcinoids of unknown primary origin.19

Metastases in carcinoid tumors are common, with one study noting that the highest frequency of small intestinal metastases was from the ileal subset.20 At the time of diagnosis, 58% to 64% of patients with small intestine carcinoid tumors already had nonlocalized disease, with frequent sites being the lymph nodes (89.8%), liver (44.1%), lungs (13.6%), and peritoneum (13.6%). Regional and distant metastases are associated with substantially worse prognoses, with survival rates of 71.7% and 38.5%, respectively.1 Treatment of symptomatic unresectable disease focuses on symptomatic management with somatostatin analogs that also control tumor growth.21

We present a rare case of scalp metastasis of a carcinoid tumor of the terminal ileum. Distant metastasis is associated with poorer prognosis and should be considered in patients with a known history of a carcinoid tumor.

Acknowledgment—We would like to acknowledge the Research Histology and Tissue Imaging Core at University of Illinois Chicago Research Resources Center for the immunohistochemistry studies.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, et al. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Tomassetti P. Clinical aspects of carcinoid tumours. Italian J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31(suppl 2):S143-S146.

- Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2 pt 1):228-236.

- Garcia A, Mays S, Silapunt S. Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma in the skin. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9052w9x1.

- Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Grillo A, et al. Unexpected response to palliative radiotherapy for subcutaneous metastases of an advanced small cell pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report of two different radiation schedules. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:311.

- Devnani B, Kumar R, Pathy S, et al. Cutaneous metastases from neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: an unusual metastatic lesion from an uncommon malignancy. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018; 42:527-533.

- Falto-Aizpurua L, Seyfer S, Krishnan B, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor. Cutis. 2017;99:E13-E15.

- Dhingra R, Tse JY, Saif MW. Cutaneous metastasis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-Nets)[published online September 8, 2018]. JOP. 2018;19.

- Jedrych J, Busam K, Klimstra DS, et al. Cutaneous metastases as an initial manifestation of visceral well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor: a report of four cases and a review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:113-122.

- Lloyd RV. Practical markers used in the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2003;14:293-301.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141:1490-1502.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Calabuig-Fariñas S, et al. Superficial Ewing’s sarcoma family of tumors: a clinicopathological study with differential diagnoses. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:636-643.

- D’Cruze L, Dutta R, Rao S, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry in the analysis of the spectrum of small round cell tumours at a tertiary care centre. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1377-1382.

- Chirila DN, Turdeanu NA, Constantea NA, et al. Multiple malignant tumors. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2013;108:498-502.

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628-1638.

- Lin X, Saad RS, Luckasevic TM, et al. Diagnostic value of CDX-2 and TTF-1 expressions in separating metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms of unknown origin. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2007;15:407-414.

- Olney JR, Urdaneta LF, Al-Jurf AS, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Am Surg. 1985;51:37-41.

- Strosberg JR, Halfdanarson TR, Bellizzi AM, et al. The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guidelines for surveillance and medical management of midgut neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2017;46:707-714.

A 47-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain and flushing. She had a history of a midgut carcinoid that originated in the ileum with metastasis to the colon, liver, and pancreas. Dermatologic examination revealed a firm, nontender, mobile, 7-mm scalp nodule with a pink-purple overlying epidermis. The lesion was associated with a slight decrease in hair density. A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Pumping iron improves longevity in older adults

with the strongest effects observed when the two types of exercise are combined, new research shows.

“The novel finding from our study is that weight lifting is independently associated with lower all-cause and CVD-specific mortality, regardless of aerobic activity,” first author Jessica Gorzelitz, PhD, said in an interview.

“What’s less surprising – but consistent and nonetheless noteworthy – is that weight lifting in combination with aerobic exercise provides the lowest...risk for mortality in older adults,” added Dr. Gorzelitz, an assistant professor of health promotion in the department of health and human physiology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Those who undertook weight lifting and aerobic exercise in combination had around a 40% lower risk of death than those who reported no moderate to vigorous aerobic activity or weight lifting. The findings were recently published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Physical activity guidelines generally recommend regular moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity, in addition to at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening exercise for all major muscle groups for adults to improve health and boost longevity.

However, few observational studies have examined the association between muscle strengthening and mortality, and even fewer have looked specifically at the benefits of weight lifting, Dr. Gorzelitz said.

Benefit of weight lifting stronger in women than men

To investigate, Dr. Gorzelitz and coauthors evaluated data on participants in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, which, initiated in 1993, and involved adults aged 55-74 at 10 U.S. cancer centers.

Thirteen years into the trial, in 2006, participants completed follow-up questionnaires that included an assessment of weight lifting (not included in a baseline survey).

Among 99,713 participants involved in the current analysis, the mean age at the time of the follow-up questionnaire was 71.3 years. Participants had a mean body mass index of 27.8 kg/m2 and 52.6% were women.

Only about a quarter of adults (23%) reported any weight lifting activity within the previous 12 months, with fewer, at 16%, reporting regular weight lifting of between one and six times per week.

Participants’ physical aerobic activity was also assessed. Physical activity guidelines (2018) recommend at least 150-300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or 75-150 minutes per week of vigorous intensity aerobic activity or an equal combination of the two. Overall, 23.6% of participants reported activity that met the guideline for moderate to vigorous physical activity, and 8% exceeded it.

Over a median follow-up of about 9 years, 28,477 deaths occurred.

Those reporting weight lifting had a 9% lower risk of combined all-cause mortality and CVD mortality, after adjustment for any moderate to vigorous physical activity (each hazard ratio, 0.91).

Adults who met aerobic activity recommendations but did not weight lift had a 32% lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.68), while those who also reported weight lifting 1-2 times per week in addition to the aerobic activity had as much as a 41% lower risk of death (HR, 0.59), compared with adults reporting no moderate to vigorous aerobic activity or weight lifting.

The benefit of weight lifting in terms of cancer mortality was only observed without adjustment for moderate to vigorous physical activity, and was therefore considered null, which Dr. Gorzelitz said was somewhat surprising. “We will examine this association further because there could still be a signal there,” she said, noting other studies have shown that muscle strengthening activity is associated with lower cancer-specific mortality.

Of note, the benefit of weight lifting appeared stronger in women versus men, Dr. Gorzelitz said.

What are the mechanisms?

Underscoring that the results show only associations and not causation, Dr. Gorzelitz speculated that mechanisms behind a mortality benefit could include known favorable physiological changes of weight lifting.

“If people are weight lifting [to a degree] to reap strength benefits, we generally see improvement in body composition, including reductions in fat and improvements in lean tissue, and we know that those changes are associated with mortality, so it could be that the weight lifting is driving the strength or body composition,” she said.

The full body response involved in weight lifting could also play a key role, she noted.

With weight lifting, “the muscles have to redirect more blood flow, the heart is pumping harder, the lungs breathe more and when the muscles are worked in that fashion, there could be other system-wide adaptations,” she said.

Furthermore, social aspects could play a role, Dr. Gorzelitz observed.

“Unlike muscle strengthening [activities] that can be done in the home setting, weight lifting typically has to be done in recreational facilities or other community centers, and considering that this is an older adult population, that social interaction could be very key for preventing isolation.”

Important limitations include that the study did not determine the nature of the weight lifting, including the duration of the weight lifting sessions or type of weight, which could feasibly range from small hand-held weights to heavier weight lifting.

The study also couldn’t show how long participants had engaged in weight lifting in terms of months or years, hence, the duration needed to see a mortality benefit was not established.

Nevertheless, the study’s finding that the group with the lowest benefits was the one reporting no aerobic or weight lifting exercise underscores the benefits of even small amounts of exercise.

“I think it’s really important to promote the importance of adding muscle strengthening, but also of any physical activity,” Dr. Gorzelitz said. “Start small, but something is better than nothing.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

with the strongest effects observed when the two types of exercise are combined, new research shows.

“The novel finding from our study is that weight lifting is independently associated with lower all-cause and CVD-specific mortality, regardless of aerobic activity,” first author Jessica Gorzelitz, PhD, said in an interview.

“What’s less surprising – but consistent and nonetheless noteworthy – is that weight lifting in combination with aerobic exercise provides the lowest...risk for mortality in older adults,” added Dr. Gorzelitz, an assistant professor of health promotion in the department of health and human physiology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Those who undertook weight lifting and aerobic exercise in combination had around a 40% lower risk of death than those who reported no moderate to vigorous aerobic activity or weight lifting. The findings were recently published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Physical activity guidelines generally recommend regular moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity, in addition to at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening exercise for all major muscle groups for adults to improve health and boost longevity.

However, few observational studies have examined the association between muscle strengthening and mortality, and even fewer have looked specifically at the benefits of weight lifting, Dr. Gorzelitz said.

Benefit of weight lifting stronger in women than men

To investigate, Dr. Gorzelitz and coauthors evaluated data on participants in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, which, initiated in 1993, and involved adults aged 55-74 at 10 U.S. cancer centers.

Thirteen years into the trial, in 2006, participants completed follow-up questionnaires that included an assessment of weight lifting (not included in a baseline survey).

Among 99,713 participants involved in the current analysis, the mean age at the time of the follow-up questionnaire was 71.3 years. Participants had a mean body mass index of 27.8 kg/m2 and 52.6% were women.

Only about a quarter of adults (23%) reported any weight lifting activity within the previous 12 months, with fewer, at 16%, reporting regular weight lifting of between one and six times per week.

Participants’ physical aerobic activity was also assessed. Physical activity guidelines (2018) recommend at least 150-300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or 75-150 minutes per week of vigorous intensity aerobic activity or an equal combination of the two. Overall, 23.6% of participants reported activity that met the guideline for moderate to vigorous physical activity, and 8% exceeded it.

Over a median follow-up of about 9 years, 28,477 deaths occurred.

Those reporting weight lifting had a 9% lower risk of combined all-cause mortality and CVD mortality, after adjustment for any moderate to vigorous physical activity (each hazard ratio, 0.91).

Adults who met aerobic activity recommendations but did not weight lift had a 32% lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.68), while those who also reported weight lifting 1-2 times per week in addition to the aerobic activity had as much as a 41% lower risk of death (HR, 0.59), compared with adults reporting no moderate to vigorous aerobic activity or weight lifting.

The benefit of weight lifting in terms of cancer mortality was only observed without adjustment for moderate to vigorous physical activity, and was therefore considered null, which Dr. Gorzelitz said was somewhat surprising. “We will examine this association further because there could still be a signal there,” she said, noting other studies have shown that muscle strengthening activity is associated with lower cancer-specific mortality.

Of note, the benefit of weight lifting appeared stronger in women versus men, Dr. Gorzelitz said.

What are the mechanisms?

Underscoring that the results show only associations and not causation, Dr. Gorzelitz speculated that mechanisms behind a mortality benefit could include known favorable physiological changes of weight lifting.

“If people are weight lifting [to a degree] to reap strength benefits, we generally see improvement in body composition, including reductions in fat and improvements in lean tissue, and we know that those changes are associated with mortality, so it could be that the weight lifting is driving the strength or body composition,” she said.

The full body response involved in weight lifting could also play a key role, she noted.

With weight lifting, “the muscles have to redirect more blood flow, the heart is pumping harder, the lungs breathe more and when the muscles are worked in that fashion, there could be other system-wide adaptations,” she said.

Furthermore, social aspects could play a role, Dr. Gorzelitz observed.

“Unlike muscle strengthening [activities] that can be done in the home setting, weight lifting typically has to be done in recreational facilities or other community centers, and considering that this is an older adult population, that social interaction could be very key for preventing isolation.”

Important limitations include that the study did not determine the nature of the weight lifting, including the duration of the weight lifting sessions or type of weight, which could feasibly range from small hand-held weights to heavier weight lifting.

The study also couldn’t show how long participants had engaged in weight lifting in terms of months or years, hence, the duration needed to see a mortality benefit was not established.

Nevertheless, the study’s finding that the group with the lowest benefits was the one reporting no aerobic or weight lifting exercise underscores the benefits of even small amounts of exercise.

“I think it’s really important to promote the importance of adding muscle strengthening, but also of any physical activity,” Dr. Gorzelitz said. “Start small, but something is better than nothing.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

with the strongest effects observed when the two types of exercise are combined, new research shows.

“The novel finding from our study is that weight lifting is independently associated with lower all-cause and CVD-specific mortality, regardless of aerobic activity,” first author Jessica Gorzelitz, PhD, said in an interview.

“What’s less surprising – but consistent and nonetheless noteworthy – is that weight lifting in combination with aerobic exercise provides the lowest...risk for mortality in older adults,” added Dr. Gorzelitz, an assistant professor of health promotion in the department of health and human physiology at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Those who undertook weight lifting and aerobic exercise in combination had around a 40% lower risk of death than those who reported no moderate to vigorous aerobic activity or weight lifting. The findings were recently published online in the British Journal of Sports Medicine.

Physical activity guidelines generally recommend regular moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity, in addition to at least 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening exercise for all major muscle groups for adults to improve health and boost longevity.

However, few observational studies have examined the association between muscle strengthening and mortality, and even fewer have looked specifically at the benefits of weight lifting, Dr. Gorzelitz said.

Benefit of weight lifting stronger in women than men

To investigate, Dr. Gorzelitz and coauthors evaluated data on participants in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, which, initiated in 1993, and involved adults aged 55-74 at 10 U.S. cancer centers.

Thirteen years into the trial, in 2006, participants completed follow-up questionnaires that included an assessment of weight lifting (not included in a baseline survey).

Among 99,713 participants involved in the current analysis, the mean age at the time of the follow-up questionnaire was 71.3 years. Participants had a mean body mass index of 27.8 kg/m2 and 52.6% were women.

Only about a quarter of adults (23%) reported any weight lifting activity within the previous 12 months, with fewer, at 16%, reporting regular weight lifting of between one and six times per week.

Participants’ physical aerobic activity was also assessed. Physical activity guidelines (2018) recommend at least 150-300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity or 75-150 minutes per week of vigorous intensity aerobic activity or an equal combination of the two. Overall, 23.6% of participants reported activity that met the guideline for moderate to vigorous physical activity, and 8% exceeded it.

Over a median follow-up of about 9 years, 28,477 deaths occurred.

Those reporting weight lifting had a 9% lower risk of combined all-cause mortality and CVD mortality, after adjustment for any moderate to vigorous physical activity (each hazard ratio, 0.91).

Adults who met aerobic activity recommendations but did not weight lift had a 32% lower risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 0.68), while those who also reported weight lifting 1-2 times per week in addition to the aerobic activity had as much as a 41% lower risk of death (HR, 0.59), compared with adults reporting no moderate to vigorous aerobic activity or weight lifting.

The benefit of weight lifting in terms of cancer mortality was only observed without adjustment for moderate to vigorous physical activity, and was therefore considered null, which Dr. Gorzelitz said was somewhat surprising. “We will examine this association further because there could still be a signal there,” she said, noting other studies have shown that muscle strengthening activity is associated with lower cancer-specific mortality.

Of note, the benefit of weight lifting appeared stronger in women versus men, Dr. Gorzelitz said.

What are the mechanisms?

Underscoring that the results show only associations and not causation, Dr. Gorzelitz speculated that mechanisms behind a mortality benefit could include known favorable physiological changes of weight lifting.

“If people are weight lifting [to a degree] to reap strength benefits, we generally see improvement in body composition, including reductions in fat and improvements in lean tissue, and we know that those changes are associated with mortality, so it could be that the weight lifting is driving the strength or body composition,” she said.

The full body response involved in weight lifting could also play a key role, she noted.

With weight lifting, “the muscles have to redirect more blood flow, the heart is pumping harder, the lungs breathe more and when the muscles are worked in that fashion, there could be other system-wide adaptations,” she said.

Furthermore, social aspects could play a role, Dr. Gorzelitz observed.

“Unlike muscle strengthening [activities] that can be done in the home setting, weight lifting typically has to be done in recreational facilities or other community centers, and considering that this is an older adult population, that social interaction could be very key for preventing isolation.”

Important limitations include that the study did not determine the nature of the weight lifting, including the duration of the weight lifting sessions or type of weight, which could feasibly range from small hand-held weights to heavier weight lifting.

The study also couldn’t show how long participants had engaged in weight lifting in terms of months or years, hence, the duration needed to see a mortality benefit was not established.

Nevertheless, the study’s finding that the group with the lowest benefits was the one reporting no aerobic or weight lifting exercise underscores the benefits of even small amounts of exercise.

“I think it’s really important to promote the importance of adding muscle strengthening, but also of any physical activity,” Dr. Gorzelitz said. “Start small, but something is better than nothing.”

The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE

Colonoscopy lowers CRC risk and death, but not by much: NordICC

VIENNA – the 10-year follow-up of the large, multicenter, randomized Northern-European Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (NordICC) trial shows.

In effect, this means the number needed to invite to undergo screening to prevent one case of colorectal cancer is 455 (95% confidence interval, 270-1,429), the researchers determined.

The results were presented at the United European Gastroenterology Week 2022 meeting and were published simultaneously in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the study, which was designed to be truly population based and to mimic national colorectal cancer screening programs, provide an estimate of the effect of screening colonoscopy in the general population.

The primary outcome was determined on an intention-to-screen basis. All persons who were invited to undergo colonoscopy screening were compared with people who received usual care (that is, received no invitation or screening). At UEG 2022, the researchers presented the interim 10-year colorectal cancer risk, which was found to be 0.98%, compared to 1.20%. This represents a risk reduction of 18% among colonoscopy invitees (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.93). During the study period, 259 cases of colorectal cancer were diagnosed in the invited group versus622 in the usual-care group.

The risk of death from colorectal cancer was 0.28% in the invited group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). The risk of death from any cause was similar in both the invited group and the usual-care group, at 11.03% and 11.04%, respectively (RR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.96-1.04).

The authors noted that the benefit would have been greater had more people undergone screening; only 42% of those who were invited actually underwent colonoscopy. In an adjusted analysis, had all those who had been invited to undergo screening undergone colonoscopy, the 10-year risk of colorectal cancer would have decreased from 1.22% to 0.84%, and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death would have fallen from 0.30% to 0.15%.

The researchers, led by gastroenterologist Michael Bretthauer, MD, from the department of medicine, gastrointestinal endoscopy, University of Oslo, who presented the data at UEG 2022 on behalf of the NordICC study group, acknowledged that, despite the “observed appreciable reductions in relative risks, the absolute risks of the risk of colorectal cancer and even more so of colorectal cancer–related death were lower than those in previous screening trials and lower than what we anticipated when the trial was planned.”

However, they add that “optimism related to the effects of screening on colorectal cancer–related death may be warranted in light of the 50% decrease observed in adjusted per-protocol analyses.”

With his coauthors, Dr. Bretthauer wrote that even their adjusted findings “probably underestimated the benefit because, as in most other large-scale trials of colorectal cancer screening, we could not adjust for all important confounders in all countries.”

Dr. Bretthauer also noted that results were similar to those achieved through sigmoidoscopy screening. By close comparison, sigmoidoscopy studies show the risk of colorectal cancer is reduced between 33% and 40%, according to per protocol analyses. “These results suggest that colonoscopy screening might not be substantially better in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer than sigmoidoscopy.”

Real-world, population-based study

NordICC is an ongoing, pragmatic study and is the first randomized trial to quantify the possible benefit of colonoscopy screening on risk of colorectal cancer and related death.

Researchers recruited healthy men and women from registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Most participants came from Poland (54,258), followed by Norway (26,411) and Sweden (3,646). Data from the Netherlands could not be included owing to data protection law.

At baseline, 84,585 participants aged 55-64 years were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio either to receive an invitation to undergo a single screening colonoscopy (28,220; invited) or to undergo usual care in each participant country (56,365; no invitation or screening).

Any colorectal cancer lesions detected were removed, whenever possible. The primary endpoints were the risks of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death. The secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

‘Modest effectiveness,’ but longer follow-up to give fuller picture

In an editorial that accompanied publication of the study, Jason A. Dominitz, MD, from the division of gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle, and Douglas J. Robertson, MD, from White River Junction (Vt.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center, commented on the possible reasons for the low reduction in incident cancer and deaths seen in NordICC.

They pointed out that cohort studies suggest a 40%-69% decrease in the incidence of colorectal cancer and a 29%-88% decrease in the risk of death with colonoscopy. However, they noted that “cohort studies probably overestimate the real-world effectiveness of colonoscopy because of the inability to adjust for important factors such as incomplete adherence to testing and the tendency of healthier persons to seek preventive care.”

Referring to Dr. Bretthauer’s point about attendance to screening, Dr. Dominitz and Dr. Robertson added that, in the United States, colonoscopy is the predominant form of screening for colorectal cancer and that in countries where colonoscopy is less established, participation may be very different.

“The actual effectiveness of colonoscopy in populations that are more accepting of colonoscopy could more closely resemble the effectiveness shown in the per-protocol analysis in this trial,” they wrote.

The editorialists also pointed out that the benefits of screening colonoscopy take time to be realized “because the incidence of colorectal cancer is initially increased when presymptomatic cancers are identified.” A repeat and final analysis of the NordICC data is due at 15 years’ follow-up.

In addition, they noted that “colonoscopy is highly operator dependent” and that the adenoma detection rate is variable and affects cancer risk and related mortality.

Given the “modest effectiveness” of screening colonoscopy in the trial, they asserted that, “if the trial truly represents the real-world performance of population-based screening colonoscopy, it might be hard to justify the risk and expense of this form of screening when simpler, less-invasive strategies (e.g., sigmoidoscopy and FIT [fecal immunochemical test]) are available.”

However, they also noted that “additional analyses, including longer follow up and results from other ongoing comparative effectiveness trials, will help us to fully understand the benefits of this test.”

Also commenting on the study was Michiel Maas, MD, from the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, told this news organization that he agreed that the absolute effect on colorectal cancer risk or colorectal cancer–related death was not as high as expected and may be disappointing.

But Dr. Maas said that “around half of the patients in the study did not undergo colonoscopy, which may have negatively impacted the results.

“An additional factor, which can be influential in colonoscopy studies, is the potential variability in detection rates between operators/endoscopists,” he said.

Looking to the future, Dr. Maas noted that “AI [artificial intelligence] or computer-aided detection can level this playing field in detection rates.

“Nevertheless, this is a very interesting study, which sheds a new light on the efficacy on screening colonoscopies,” he said.

Dr. Bretthauer has relationships with Paion, Cybernet, and the Norwegian Council of Research. Dr. Dominitz is cochair of VA Cooperative Studies Program #577: “Colonoscopy vs. Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) in Reducing Mortality from Colorectal Cancer” (the CONFIRM Study), which is funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Robertson is national cochair (with Dr. Dominitz) of the CONFIRM trial and has received personal fees from Freenome outside of the submitted work. Dr. Maas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA – the 10-year follow-up of the large, multicenter, randomized Northern-European Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (NordICC) trial shows.

In effect, this means the number needed to invite to undergo screening to prevent one case of colorectal cancer is 455 (95% confidence interval, 270-1,429), the researchers determined.

The results were presented at the United European Gastroenterology Week 2022 meeting and were published simultaneously in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the study, which was designed to be truly population based and to mimic national colorectal cancer screening programs, provide an estimate of the effect of screening colonoscopy in the general population.

The primary outcome was determined on an intention-to-screen basis. All persons who were invited to undergo colonoscopy screening were compared with people who received usual care (that is, received no invitation or screening). At UEG 2022, the researchers presented the interim 10-year colorectal cancer risk, which was found to be 0.98%, compared to 1.20%. This represents a risk reduction of 18% among colonoscopy invitees (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.93). During the study period, 259 cases of colorectal cancer were diagnosed in the invited group versus622 in the usual-care group.

The risk of death from colorectal cancer was 0.28% in the invited group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). The risk of death from any cause was similar in both the invited group and the usual-care group, at 11.03% and 11.04%, respectively (RR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.96-1.04).

The authors noted that the benefit would have been greater had more people undergone screening; only 42% of those who were invited actually underwent colonoscopy. In an adjusted analysis, had all those who had been invited to undergo screening undergone colonoscopy, the 10-year risk of colorectal cancer would have decreased from 1.22% to 0.84%, and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death would have fallen from 0.30% to 0.15%.

The researchers, led by gastroenterologist Michael Bretthauer, MD, from the department of medicine, gastrointestinal endoscopy, University of Oslo, who presented the data at UEG 2022 on behalf of the NordICC study group, acknowledged that, despite the “observed appreciable reductions in relative risks, the absolute risks of the risk of colorectal cancer and even more so of colorectal cancer–related death were lower than those in previous screening trials and lower than what we anticipated when the trial was planned.”

However, they add that “optimism related to the effects of screening on colorectal cancer–related death may be warranted in light of the 50% decrease observed in adjusted per-protocol analyses.”

With his coauthors, Dr. Bretthauer wrote that even their adjusted findings “probably underestimated the benefit because, as in most other large-scale trials of colorectal cancer screening, we could not adjust for all important confounders in all countries.”

Dr. Bretthauer also noted that results were similar to those achieved through sigmoidoscopy screening. By close comparison, sigmoidoscopy studies show the risk of colorectal cancer is reduced between 33% and 40%, according to per protocol analyses. “These results suggest that colonoscopy screening might not be substantially better in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer than sigmoidoscopy.”

Real-world, population-based study

NordICC is an ongoing, pragmatic study and is the first randomized trial to quantify the possible benefit of colonoscopy screening on risk of colorectal cancer and related death.

Researchers recruited healthy men and women from registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Most participants came from Poland (54,258), followed by Norway (26,411) and Sweden (3,646). Data from the Netherlands could not be included owing to data protection law.

At baseline, 84,585 participants aged 55-64 years were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio either to receive an invitation to undergo a single screening colonoscopy (28,220; invited) or to undergo usual care in each participant country (56,365; no invitation or screening).

Any colorectal cancer lesions detected were removed, whenever possible. The primary endpoints were the risks of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death. The secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

‘Modest effectiveness,’ but longer follow-up to give fuller picture

In an editorial that accompanied publication of the study, Jason A. Dominitz, MD, from the division of gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle, and Douglas J. Robertson, MD, from White River Junction (Vt.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center, commented on the possible reasons for the low reduction in incident cancer and deaths seen in NordICC.

They pointed out that cohort studies suggest a 40%-69% decrease in the incidence of colorectal cancer and a 29%-88% decrease in the risk of death with colonoscopy. However, they noted that “cohort studies probably overestimate the real-world effectiveness of colonoscopy because of the inability to adjust for important factors such as incomplete adherence to testing and the tendency of healthier persons to seek preventive care.”

Referring to Dr. Bretthauer’s point about attendance to screening, Dr. Dominitz and Dr. Robertson added that, in the United States, colonoscopy is the predominant form of screening for colorectal cancer and that in countries where colonoscopy is less established, participation may be very different.

“The actual effectiveness of colonoscopy in populations that are more accepting of colonoscopy could more closely resemble the effectiveness shown in the per-protocol analysis in this trial,” they wrote.

The editorialists also pointed out that the benefits of screening colonoscopy take time to be realized “because the incidence of colorectal cancer is initially increased when presymptomatic cancers are identified.” A repeat and final analysis of the NordICC data is due at 15 years’ follow-up.

In addition, they noted that “colonoscopy is highly operator dependent” and that the adenoma detection rate is variable and affects cancer risk and related mortality.

Given the “modest effectiveness” of screening colonoscopy in the trial, they asserted that, “if the trial truly represents the real-world performance of population-based screening colonoscopy, it might be hard to justify the risk and expense of this form of screening when simpler, less-invasive strategies (e.g., sigmoidoscopy and FIT [fecal immunochemical test]) are available.”

However, they also noted that “additional analyses, including longer follow up and results from other ongoing comparative effectiveness trials, will help us to fully understand the benefits of this test.”

Also commenting on the study was Michiel Maas, MD, from the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, told this news organization that he agreed that the absolute effect on colorectal cancer risk or colorectal cancer–related death was not as high as expected and may be disappointing.

But Dr. Maas said that “around half of the patients in the study did not undergo colonoscopy, which may have negatively impacted the results.

“An additional factor, which can be influential in colonoscopy studies, is the potential variability in detection rates between operators/endoscopists,” he said.

Looking to the future, Dr. Maas noted that “AI [artificial intelligence] or computer-aided detection can level this playing field in detection rates.

“Nevertheless, this is a very interesting study, which sheds a new light on the efficacy on screening colonoscopies,” he said.

Dr. Bretthauer has relationships with Paion, Cybernet, and the Norwegian Council of Research. Dr. Dominitz is cochair of VA Cooperative Studies Program #577: “Colonoscopy vs. Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) in Reducing Mortality from Colorectal Cancer” (the CONFIRM Study), which is funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Robertson is national cochair (with Dr. Dominitz) of the CONFIRM trial and has received personal fees from Freenome outside of the submitted work. Dr. Maas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA – the 10-year follow-up of the large, multicenter, randomized Northern-European Initiative on Colorectal Cancer (NordICC) trial shows.

In effect, this means the number needed to invite to undergo screening to prevent one case of colorectal cancer is 455 (95% confidence interval, 270-1,429), the researchers determined.

The results were presented at the United European Gastroenterology Week 2022 meeting and were published simultaneously in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the study, which was designed to be truly population based and to mimic national colorectal cancer screening programs, provide an estimate of the effect of screening colonoscopy in the general population.

The primary outcome was determined on an intention-to-screen basis. All persons who were invited to undergo colonoscopy screening were compared with people who received usual care (that is, received no invitation or screening). At UEG 2022, the researchers presented the interim 10-year colorectal cancer risk, which was found to be 0.98%, compared to 1.20%. This represents a risk reduction of 18% among colonoscopy invitees (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.93). During the study period, 259 cases of colorectal cancer were diagnosed in the invited group versus622 in the usual-care group.

The risk of death from colorectal cancer was 0.28% in the invited group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64-1.16). The risk of death from any cause was similar in both the invited group and the usual-care group, at 11.03% and 11.04%, respectively (RR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.96-1.04).

The authors noted that the benefit would have been greater had more people undergone screening; only 42% of those who were invited actually underwent colonoscopy. In an adjusted analysis, had all those who had been invited to undergo screening undergone colonoscopy, the 10-year risk of colorectal cancer would have decreased from 1.22% to 0.84%, and the risk of colorectal cancer–related death would have fallen from 0.30% to 0.15%.

The researchers, led by gastroenterologist Michael Bretthauer, MD, from the department of medicine, gastrointestinal endoscopy, University of Oslo, who presented the data at UEG 2022 on behalf of the NordICC study group, acknowledged that, despite the “observed appreciable reductions in relative risks, the absolute risks of the risk of colorectal cancer and even more so of colorectal cancer–related death were lower than those in previous screening trials and lower than what we anticipated when the trial was planned.”

However, they add that “optimism related to the effects of screening on colorectal cancer–related death may be warranted in light of the 50% decrease observed in adjusted per-protocol analyses.”

With his coauthors, Dr. Bretthauer wrote that even their adjusted findings “probably underestimated the benefit because, as in most other large-scale trials of colorectal cancer screening, we could not adjust for all important confounders in all countries.”

Dr. Bretthauer also noted that results were similar to those achieved through sigmoidoscopy screening. By close comparison, sigmoidoscopy studies show the risk of colorectal cancer is reduced between 33% and 40%, according to per protocol analyses. “These results suggest that colonoscopy screening might not be substantially better in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer than sigmoidoscopy.”

Real-world, population-based study

NordICC is an ongoing, pragmatic study and is the first randomized trial to quantify the possible benefit of colonoscopy screening on risk of colorectal cancer and related death.

Researchers recruited healthy men and women from registries in Poland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands between 2009 and 2014. Most participants came from Poland (54,258), followed by Norway (26,411) and Sweden (3,646). Data from the Netherlands could not be included owing to data protection law.

At baseline, 84,585 participants aged 55-64 years were randomly assigned in a 1:2 ratio either to receive an invitation to undergo a single screening colonoscopy (28,220; invited) or to undergo usual care in each participant country (56,365; no invitation or screening).

Any colorectal cancer lesions detected were removed, whenever possible. The primary endpoints were the risks of colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer–related death. The secondary endpoint was death from any cause.

‘Modest effectiveness,’ but longer follow-up to give fuller picture

In an editorial that accompanied publication of the study, Jason A. Dominitz, MD, from the division of gastroenterology, University of Washington, Seattle, and Douglas J. Robertson, MD, from White River Junction (Vt.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center, commented on the possible reasons for the low reduction in incident cancer and deaths seen in NordICC.

They pointed out that cohort studies suggest a 40%-69% decrease in the incidence of colorectal cancer and a 29%-88% decrease in the risk of death with colonoscopy. However, they noted that “cohort studies probably overestimate the real-world effectiveness of colonoscopy because of the inability to adjust for important factors such as incomplete adherence to testing and the tendency of healthier persons to seek preventive care.”

Referring to Dr. Bretthauer’s point about attendance to screening, Dr. Dominitz and Dr. Robertson added that, in the United States, colonoscopy is the predominant form of screening for colorectal cancer and that in countries where colonoscopy is less established, participation may be very different.

“The actual effectiveness of colonoscopy in populations that are more accepting of colonoscopy could more closely resemble the effectiveness shown in the per-protocol analysis in this trial,” they wrote.

The editorialists also pointed out that the benefits of screening colonoscopy take time to be realized “because the incidence of colorectal cancer is initially increased when presymptomatic cancers are identified.” A repeat and final analysis of the NordICC data is due at 15 years’ follow-up.

In addition, they noted that “colonoscopy is highly operator dependent” and that the adenoma detection rate is variable and affects cancer risk and related mortality.

Given the “modest effectiveness” of screening colonoscopy in the trial, they asserted that, “if the trial truly represents the real-world performance of population-based screening colonoscopy, it might be hard to justify the risk and expense of this form of screening when simpler, less-invasive strategies (e.g., sigmoidoscopy and FIT [fecal immunochemical test]) are available.”

However, they also noted that “additional analyses, including longer follow up and results from other ongoing comparative effectiveness trials, will help us to fully understand the benefits of this test.”

Also commenting on the study was Michiel Maas, MD, from the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, Radboud UMC, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, told this news organization that he agreed that the absolute effect on colorectal cancer risk or colorectal cancer–related death was not as high as expected and may be disappointing.

But Dr. Maas said that “around half of the patients in the study did not undergo colonoscopy, which may have negatively impacted the results.

“An additional factor, which can be influential in colonoscopy studies, is the potential variability in detection rates between operators/endoscopists,” he said.

Looking to the future, Dr. Maas noted that “AI [artificial intelligence] or computer-aided detection can level this playing field in detection rates.

“Nevertheless, this is a very interesting study, which sheds a new light on the efficacy on screening colonoscopies,” he said.

Dr. Bretthauer has relationships with Paion, Cybernet, and the Norwegian Council of Research. Dr. Dominitz is cochair of VA Cooperative Studies Program #577: “Colonoscopy vs. Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) in Reducing Mortality from Colorectal Cancer” (the CONFIRM Study), which is funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Robertson is national cochair (with Dr. Dominitz) of the CONFIRM trial and has received personal fees from Freenome outside of the submitted work. Dr. Maas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM UEG 2022

Gut microbiota disruption a driver of aggression in schizophrenia?

However, at least one expert expressed concerns over the study’s conclusions.

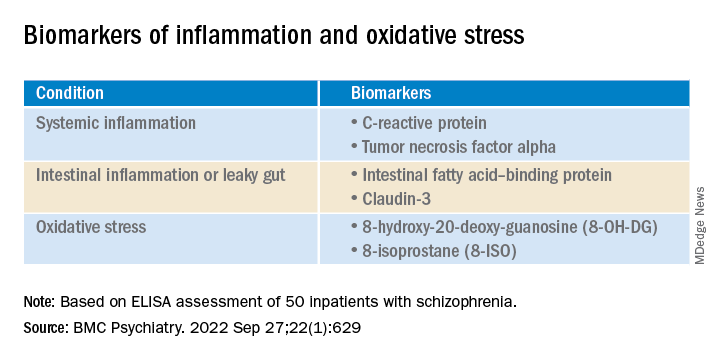

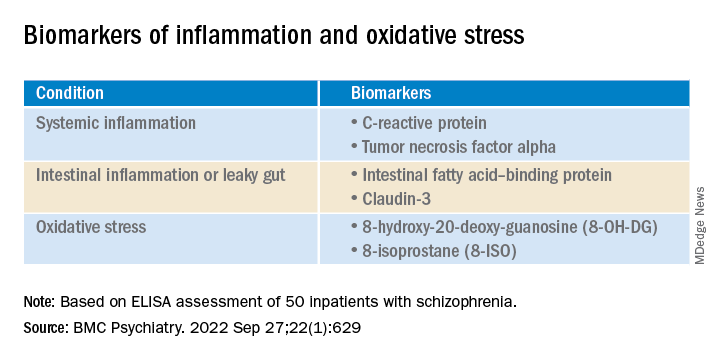

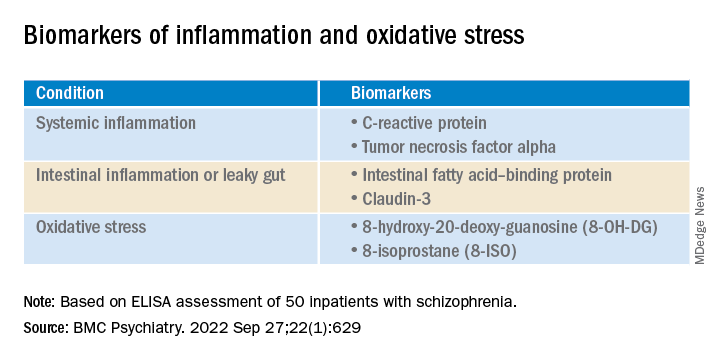

Results from a study of 50 inpatients with schizophrenia showed significantly higher pro-inflammation, pro-oxidation, and leaky gut biomarkers in those with aggression vs. their peers who did not display aggression.

In addition, those with aggression showed less alpha diversity and evenness of the fecal bacterial community, lower levels of several beneficial gut bacteria, and higher levels of the fecal genera Prevotella.

Six short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and six neurotransmitters were also lower in the aggression vs. no-aggression groups.

“The present study was the first to compare the state of inflammation, oxidation, intestinal microbiota, and metabolites” in inpatients with schizophrenia and aggression, compared with those who did not show aggression, write the investigators, led by Hongxin Deng, department of psychiatry, Zhumadian (China) Psychiatric Hospital.

“Results indicate pro-inflammation, pro-oxidation and leaky gut phenotypes relating to enteric dysbacteriosis and microbial SCFAs feature the aggression in [individuals with schizophrenia], which provides clues for future microbial-based or anti-inflammatory/oxidative therapies on aggression,” they add.

The findings were published online in BMC Psychiatry.

Unknown pathogenesis

Although emerging evidence suggests that schizophrenia “may augment the propensity for aggression incidence about fourfold to sevenfold,” the pathogenesis of aggression “remains largely unknown,” the investigators note.

The same researchers previously found an association between the systemic pro-inflammation response and the onset or severity of aggression in schizophrenia, “possibly caused by leaky gut-induced bacterial translocation.”

The researchers suggest that peripheral cytokines “could cross the blood-brain barrier, thus precipitating changes in mood and behavior through hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.”

However, they note that the pro-inflammation phenotype is “often a synergistic effect of multiple causes.” Of these, chronic pro-oxidative stress has been shown to contribute to aggression onset in intermittent explosive disorder, but this association has rarely been confirmed in patients with schizophrenia.

In addition, increasing evidence points to enteric dysbacteriosis and dysbiosis of intestinal flora metabolites, including SCFAs or neurotransmitters, as potentially “integral parts of psychiatric disorders’ pathophysiology” by changing the state of both oxidative stress and inflammation.

The investigators hypothesized that the systemic pro-inflammation phenotype in aggression-affected schizophrenia cases “involves alterations to gut microbiota and its metabolites, leaky gut, and oxidative stress.” However, the profiles of these variables and their interrelationships have been “poorly investigated” in inpatients with schizophrenia and aggression.

To fill this gap, they assessed adult psychiatric inpatients with schizophrenia and aggressive behaviors and inpatients with schizophrenia but no aggressive behavior within 1 week before admission (n = 25 per group; mean age, 33.52 years, and 32.88 years, respectively; 68% and 64% women, respectively).

They collected stool samples from each patient and used enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) to detect fecal calprotectin protein, an indicator of intestinal inflammation. They also collected fasting peripheral blood samples, using ELISA to detect several biomarkers.

The researchers also used the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) to characterize aggressive behaviors and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale to characterize psychiatric symptoms.

‘Vital role’

Significantly higher biomarkers for systemic pro-inflammation, pro-oxidation and leaky gut were found in the aggression vs the no-aggression group (all P < .05).

After controlling for potential confounders, the researchers also found positive associations between MOAS scores and biomarkers, both serum and fecal.

There were also positive associations between serum 8-hydroxy-20-deoxy-guanosine (8-OH-DG) or 8-isoprostane (8-ISO) and systemic inflammatory biomarkers (all R > 0; P < .05).

In addition, the alpha diversity and evenness of the fecal bacterial community were lower in the aggression vs. no aggression groups.

When the researchers compared the relative abundance of the top 15 genera composition of intestinal microflora in the two groups, Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, Blautia, Bifidobacterium, Collinsella, and Eubacterium coprostanoligenes were “remarkably reduced” in the group with aggression, whereas the abundance of fecal genera Prevotella was significantly increased (all corrected P < .001).

In the patients who had schizophrenia with aggression, levels of six SCFAs and six neurotransmitters were much lower than in the patients with schizophrenia but no aggression (all P < .05).

Inpatients with schizophrenia and aggression “had dramatically increased serum level of 8-OH-DG (nucleic acid oxidation biomarker) and 8-ISO (lipid oxidation biomarker) than those without, and further correlation analysis also showed positive correlativity between pro-oxidation and systemic pro-inflammation response or aggression severity,” the investigators write.

The findings “collectively suggest the cocontributory role of systemic pro-inflammation and pro-oxidation in the development of aggression” in schizophrenia, they add. “Gut dysbacteriosis with leaky gut seems to play a vital role in the pathophysiology.”

Correlation vs. causality

Commenting for this article, Emeran Mayer, MD, distinguished research professor of medicine at the G. Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience and UCLA Brain Gut Microbiome Center, Los Angeles, said that “at first glance, it is interesting that the behavioral trait of aggression but not the diagnosis of schizophrenia showed the differences in markers of systemic inflammation, increased gut permeability, and microbiome parameters.”

However, like many such descriptive studies, the research is flawed by comparing two patient groups and concluding causality between the biomarkers and the behavior traits, added Dr. Mayer, who was not involved with the study.

The study’s shortcomings include its small sample size as well as several confounding factors – particularly diet, sleep, exercise, and stress and anxiety levels – that were not considered, he said. The study also lacked a control group with high levels of aggression but without schizophrenia.

“The observed changes in intestinal permeability, unscientifically referred to as ‘leaky gut,’ as well as the gut microbiome differences, could be secondary to chronically increased sympathetic nervous system activation in the high aggression group,” Dr. Mayer said. “This is an interesting hypothesis which should be discussed and should have been addressed in this study.”

The differences in gut microbial composition and SCFA production “could be secondary to differences in plant-based diet components,” Dr. Mayer speculated, wondering how well dietary intake was controlled.

“Overall, it is an interesting descriptive study, which unfortunately does not contribute significantly to a better understanding of the role of the brain-gut microbiome system in schizophrenic patients,” he said.

The study was funded by a grant from China Postdoctoral Science Foundation. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mayer is a scientific advisory board member of Danone, Axial Therapeutics, Viome, Amare, Mahana Therapeutics, Pendulum, Bloom Biosciences, and APC Microbiome Ireland.