User login

End the Routine Shackling of Incarcerated Inpatients

The police shooting of Jacob Blake, an unarmed Wisconsin man, during an arrest in August 2020, led to more protests in a summer filled with calls against the unequal application of police force. Outrage grew as it was revealed that Blake, paralyzed from his waist down and not yet convicted of a crime, was still handcuffed to his hospital bed while receiving treatment.1 To many this seemed unusually cruel, but to those tasked with caring for incarcerated patients, it is all too familiar. Given the high rates of incarceration in the United States and the increased medical needs of this population, caring for those in custody is unavoidable for many physicians and hospitals. Though safety should be paramount, the universal application of metal handcuffs or leg cuffs by law enforcement officials, a process known as shackling, can lead to a variety of harms and should be abandoned.

BACKGROUND

The United States incarcerates more individuals both in total numbers and per capita than any other country in the world. This is currently believed to be more than two million people on any given day or more than 650 persons per 100,000 population.2 Incarceration occurs in jails, which are locally run facilities holding individuals on short sentences or those not yet convicted who are unable to afford bail before their trials (pretrial), or prisons, which are state and federally run facilities that house those with long sentences. When an incarcerated person experiences a medical emergency requiring hospitalization, they are either treated in the correctional facility or transferred to a local hospital for a higher level of care. Some hospitals are equipped with security measures similar to those of a correctional facility, with secure floors or wings dedicated solely to the care of the incarcerated. Secure units are more commonly seen in hospitals associated with prisons rather than local jails. Other hospitals house incarcerated patients in the same rooms as the public population, and thus movement is restricted by other means.3 Most commonly, this is done with a hard metal shackle resembling a handcuff with one end attached to the leg or wrist and the other end attached to the bed. Some agencies require more restraints, often requiring the use of wrist cuffs and leg cuffs concurrently for the entire duration of a patient’s hospitalization.4 In our experience, agencies apply these restraints universally, regardless of age, illness, mobility, or pretrial status.

Restraint practices are rooted in a concern for practitioner and public safety and bear merit. A patient from a correctional facility is usually guarded by just one officer in lieu of the multiple security measures at a jail or prison facility. Nonsecured hospitals have become sites of multiple escapes by incarcerated inpatients, given the lack of secured doors and the multiple movements during the admission and discharge processes.5 Furthermore, violence against hospital staff is now a focus issue in many hospitals and is no longer accepted as just “part of the job.” In several high-profile incidents, incarcerated inpatients have harmed staff, including one at our own institution, when an incarcerated patient held a makeshift weapon to a student’s throat.6

LEGAL CHALLENGES

The use of shackles during hospital visits has been challenged in US courts and routinely upheld. In one case, an incarcerated patient with renal failure received injuries after his leg edema was so severe that “at one point the shackles themselves were barely visible.”7 Though he was injured, the shackles were determined to have served a penological purpose outside of punishment, such as preventing escape, and the injuries were the result of the patient’s guards not following protocol. British courts have taken a different stance, ruling for an incarcerated patient who challenged the use of cuffs during three outpatient appointments and one inpatient admission.8 While the cuffs in the outpatient setting were deemed acceptable (as they were removed during the medical visit itself), they remained during the duration of the inpatient stay. This was deemed in violation of Title I/Article 3 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, Dignity/The right to integrity of the person. One area in US healthcare where shackling has been roundly condemned is the peripartum shackling of pregnant women. Though courts have had a mixed record to challenges, activism and advocacy have led to the banning of the practice in 23 states, though in most states significant exemptions exist.9 Through the First Step Act of 2018, the federal government banned peripartum shackling for all federal prisoners, but as most incarcerations are under state or local control, a considerable number of incarcerated pregnant women can legally be shackled during their deliveries.

RISKS OF SHACKLING

Legal and safety concerns aside, the shackling of incarcerated patients carries enormous risk. The use of medical restraints in hospitals has decreased over the past few decades, given their proven harms in increasing falls, exacerbating delirium, and increasing the risk of in-hospital death.10 There is no reason to believe that trading a soft medical restraint for a metal leg or wrist cuff would not confer the same risk. Additionally, metal law enforcement cuffs are not designed with patient safety in mind and have been known to cause specific nerve injuries, or handcuff neuropathy. This can occur when placement is too tight or when a patient struggles against them, as could happen with an agitated or delirious patient. The bar for removal, even briefly for an exam, is also much higher than that of a medical restraint, leading to a greater likelihood that certain aspects of the physical exam, such as gait or strength assessment, may not be adequately performed. In one small survey, British physicians reported often performing an exam while the patient was cuffed and with a guard in the room, despite country guidelines against both practices.11

Additionally, marginalized communities are disproportionately incarcerated and have a fraught and tenuous relationship with the healthcare system. Black patients routinely report greater mistrust than White patients in the outcomes of care and the motivations of physicians, in large part due to past and current discrimination and the medical community’s history of experimentation.12 A shackled patient may view a treating physician and hospital as complicit with the practice, rather than seeing the practice as something outside of their control. If a patient’s sole interaction with inpatient medicine involves shackling, it risks damaging whatever fragile physician-patient relationship may exist and could delay or limit care even further.

While the universal application of metal handcuffs or leg cuffs ensures low rates of escape or attacks on workers, it does so at the expense of vulnerable individuals. We have cared for an incarcerated elderly woman arrested for multiple traffic violations, a man with severe autism who slipped through the cracks of mental health diversion protocols and ended up in jail, and an arrested delirious man with severe alcohol withdrawal, all shackled with hard shackles on the wrists, legs, or in the final case, both. Safety and the rights of the vulnerable are not mutually exclusive, and we feel the following measures can protect both.

A WAY FORWARD

First, the universal application of shackles in the hospitalized incarcerated patient should end. If no alternative security measures are available for high-risk patients, correctional facilities must document their necessity as physicians and nurses are required to do for medical restraints. Hospitals should have processes in place for providers who feel unsafe with an unshackled patient or think a patient is unnecessarily shackled, and collegial discussions about shackling with law enforcement should be the norm. If safe to do so, shackles should routinely be removed for physical exams without question. Since law enforcement officials, rather than the hospitals, make the rules for shackling, this will take some degree of physician and administrative advocacy at the hospital level and legislative advocacy at the local and state levels.

Second, vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, those experiencing a mental health crisis, or others at risk for in-hospital delirium, should never be restrained with hard law enforcement cuffs. Restraint procedures should follow standard medical restraint procedures, and soft restraints should be used if at all possible. Given the high rates of psychiatric illness amongst the incarcerated and the role jails play in filling gaps in psychiatric care, medical admissions for those with mental illness are not rare occasions.

Finally, hospitals routinely taking care of an incarcerated population should seek to build secure units, a move that would dramatically reduce the need for shackling. In several cities, the primary referral hospitals for some of the largest jails in the country do not have units with the proper security to allow for freedom of movement, and thus, shackling persists. Creating secure units will take significant investment on the part of hospital and local authorities, but there is potential for decreasing costs due to consolidating supervision, which would lead to better patient outcomes given the above risks.

Advocating for the health of the incarcerated, even those who have not yet been convicted, is typically not a high priority for the general public. As inpatient physicians, we see the impact universal shackling has on some of our most vulnerable patients and should be their voice where they have none. Advocating for and implementing the above procedures will be a step toward improving patient care while maintaining safety.

1. Proctor C. Jacob Blake handcuffed to hospital bed, father says. Chicago Sun-Times. Updated August 27, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2020. chicago.suntimes.com/2020/8/27/21404463/jacob-blake-father-kenosha-police-shooting-hospital-bed-handcuffs

2. Maruschak LM, Minton TD. Correctional populations in the United States, 2017-2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics. August 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus1718.pdf

3. Huh K, Boucher A, Fehr S, McGaffey F, McKillop M, Schiff M. State prisons and the delivery of hospital care: how states set up and finance off-site care for incarcerated individuals. The Pew Charitable Trusts. July 2018. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/07/prisons-and-hospital-care_report.pdf

4. Haber LA, Erickson HP, Ranji SR, Ortiz GM, Pratt LA. Acute care for patients who are incarcerated: a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1561-1567. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3881

5. Mikow-Porto VA, Smith TA. The IHSSF 2011 Prisoner Escape Study. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2011;27(2):38-58.

6. Lezon D, Blakinger K. Inmate shot by deputy after holding medical student at Ben Taub. Houston Chronicle. October 6, 2016. Accessed December 29, 2020. https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Deputy-shoots-suspect-at-Ben-Taub-hopsital-9873972.php

7. Yearwood LT. Pregnant and shackled: why inmates are still giving birth cuffed and bound. The Guardian. January 24, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2020. theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jan/24/shackled-pregnant-women-prisoners-birth

8. Haslar v Megerman, 104 F.3d 178 (8th Cir. 1997).

9. FGP v Serco Plc and SSHD, EWHC 1804 (Admin) (2012).

10. Cleary K, Prescott K. The use of physical restraints in acute and long-term care: an updated review of the evidence, regulations, ethics, and legality. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2015;6(1):8-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAT.0000000000000005

11. Tuite H, Browne K, O’Neill D. Prisoners in general hospitals: doctors’ attitudes and practice. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):548-549. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7540.548-b

12. LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146-161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558700057001S07

The police shooting of Jacob Blake, an unarmed Wisconsin man, during an arrest in August 2020, led to more protests in a summer filled with calls against the unequal application of police force. Outrage grew as it was revealed that Blake, paralyzed from his waist down and not yet convicted of a crime, was still handcuffed to his hospital bed while receiving treatment.1 To many this seemed unusually cruel, but to those tasked with caring for incarcerated patients, it is all too familiar. Given the high rates of incarceration in the United States and the increased medical needs of this population, caring for those in custody is unavoidable for many physicians and hospitals. Though safety should be paramount, the universal application of metal handcuffs or leg cuffs by law enforcement officials, a process known as shackling, can lead to a variety of harms and should be abandoned.

BACKGROUND

The United States incarcerates more individuals both in total numbers and per capita than any other country in the world. This is currently believed to be more than two million people on any given day or more than 650 persons per 100,000 population.2 Incarceration occurs in jails, which are locally run facilities holding individuals on short sentences or those not yet convicted who are unable to afford bail before their trials (pretrial), or prisons, which are state and federally run facilities that house those with long sentences. When an incarcerated person experiences a medical emergency requiring hospitalization, they are either treated in the correctional facility or transferred to a local hospital for a higher level of care. Some hospitals are equipped with security measures similar to those of a correctional facility, with secure floors or wings dedicated solely to the care of the incarcerated. Secure units are more commonly seen in hospitals associated with prisons rather than local jails. Other hospitals house incarcerated patients in the same rooms as the public population, and thus movement is restricted by other means.3 Most commonly, this is done with a hard metal shackle resembling a handcuff with one end attached to the leg or wrist and the other end attached to the bed. Some agencies require more restraints, often requiring the use of wrist cuffs and leg cuffs concurrently for the entire duration of a patient’s hospitalization.4 In our experience, agencies apply these restraints universally, regardless of age, illness, mobility, or pretrial status.

Restraint practices are rooted in a concern for practitioner and public safety and bear merit. A patient from a correctional facility is usually guarded by just one officer in lieu of the multiple security measures at a jail or prison facility. Nonsecured hospitals have become sites of multiple escapes by incarcerated inpatients, given the lack of secured doors and the multiple movements during the admission and discharge processes.5 Furthermore, violence against hospital staff is now a focus issue in many hospitals and is no longer accepted as just “part of the job.” In several high-profile incidents, incarcerated inpatients have harmed staff, including one at our own institution, when an incarcerated patient held a makeshift weapon to a student’s throat.6

LEGAL CHALLENGES

The use of shackles during hospital visits has been challenged in US courts and routinely upheld. In one case, an incarcerated patient with renal failure received injuries after his leg edema was so severe that “at one point the shackles themselves were barely visible.”7 Though he was injured, the shackles were determined to have served a penological purpose outside of punishment, such as preventing escape, and the injuries were the result of the patient’s guards not following protocol. British courts have taken a different stance, ruling for an incarcerated patient who challenged the use of cuffs during three outpatient appointments and one inpatient admission.8 While the cuffs in the outpatient setting were deemed acceptable (as they were removed during the medical visit itself), they remained during the duration of the inpatient stay. This was deemed in violation of Title I/Article 3 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, Dignity/The right to integrity of the person. One area in US healthcare where shackling has been roundly condemned is the peripartum shackling of pregnant women. Though courts have had a mixed record to challenges, activism and advocacy have led to the banning of the practice in 23 states, though in most states significant exemptions exist.9 Through the First Step Act of 2018, the federal government banned peripartum shackling for all federal prisoners, but as most incarcerations are under state or local control, a considerable number of incarcerated pregnant women can legally be shackled during their deliveries.

RISKS OF SHACKLING

Legal and safety concerns aside, the shackling of incarcerated patients carries enormous risk. The use of medical restraints in hospitals has decreased over the past few decades, given their proven harms in increasing falls, exacerbating delirium, and increasing the risk of in-hospital death.10 There is no reason to believe that trading a soft medical restraint for a metal leg or wrist cuff would not confer the same risk. Additionally, metal law enforcement cuffs are not designed with patient safety in mind and have been known to cause specific nerve injuries, or handcuff neuropathy. This can occur when placement is too tight or when a patient struggles against them, as could happen with an agitated or delirious patient. The bar for removal, even briefly for an exam, is also much higher than that of a medical restraint, leading to a greater likelihood that certain aspects of the physical exam, such as gait or strength assessment, may not be adequately performed. In one small survey, British physicians reported often performing an exam while the patient was cuffed and with a guard in the room, despite country guidelines against both practices.11

Additionally, marginalized communities are disproportionately incarcerated and have a fraught and tenuous relationship with the healthcare system. Black patients routinely report greater mistrust than White patients in the outcomes of care and the motivations of physicians, in large part due to past and current discrimination and the medical community’s history of experimentation.12 A shackled patient may view a treating physician and hospital as complicit with the practice, rather than seeing the practice as something outside of their control. If a patient’s sole interaction with inpatient medicine involves shackling, it risks damaging whatever fragile physician-patient relationship may exist and could delay or limit care even further.

While the universal application of metal handcuffs or leg cuffs ensures low rates of escape or attacks on workers, it does so at the expense of vulnerable individuals. We have cared for an incarcerated elderly woman arrested for multiple traffic violations, a man with severe autism who slipped through the cracks of mental health diversion protocols and ended up in jail, and an arrested delirious man with severe alcohol withdrawal, all shackled with hard shackles on the wrists, legs, or in the final case, both. Safety and the rights of the vulnerable are not mutually exclusive, and we feel the following measures can protect both.

A WAY FORWARD

First, the universal application of shackles in the hospitalized incarcerated patient should end. If no alternative security measures are available for high-risk patients, correctional facilities must document their necessity as physicians and nurses are required to do for medical restraints. Hospitals should have processes in place for providers who feel unsafe with an unshackled patient or think a patient is unnecessarily shackled, and collegial discussions about shackling with law enforcement should be the norm. If safe to do so, shackles should routinely be removed for physical exams without question. Since law enforcement officials, rather than the hospitals, make the rules for shackling, this will take some degree of physician and administrative advocacy at the hospital level and legislative advocacy at the local and state levels.

Second, vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, those experiencing a mental health crisis, or others at risk for in-hospital delirium, should never be restrained with hard law enforcement cuffs. Restraint procedures should follow standard medical restraint procedures, and soft restraints should be used if at all possible. Given the high rates of psychiatric illness amongst the incarcerated and the role jails play in filling gaps in psychiatric care, medical admissions for those with mental illness are not rare occasions.

Finally, hospitals routinely taking care of an incarcerated population should seek to build secure units, a move that would dramatically reduce the need for shackling. In several cities, the primary referral hospitals for some of the largest jails in the country do not have units with the proper security to allow for freedom of movement, and thus, shackling persists. Creating secure units will take significant investment on the part of hospital and local authorities, but there is potential for decreasing costs due to consolidating supervision, which would lead to better patient outcomes given the above risks.

Advocating for the health of the incarcerated, even those who have not yet been convicted, is typically not a high priority for the general public. As inpatient physicians, we see the impact universal shackling has on some of our most vulnerable patients and should be their voice where they have none. Advocating for and implementing the above procedures will be a step toward improving patient care while maintaining safety.

The police shooting of Jacob Blake, an unarmed Wisconsin man, during an arrest in August 2020, led to more protests in a summer filled with calls against the unequal application of police force. Outrage grew as it was revealed that Blake, paralyzed from his waist down and not yet convicted of a crime, was still handcuffed to his hospital bed while receiving treatment.1 To many this seemed unusually cruel, but to those tasked with caring for incarcerated patients, it is all too familiar. Given the high rates of incarceration in the United States and the increased medical needs of this population, caring for those in custody is unavoidable for many physicians and hospitals. Though safety should be paramount, the universal application of metal handcuffs or leg cuffs by law enforcement officials, a process known as shackling, can lead to a variety of harms and should be abandoned.

BACKGROUND

The United States incarcerates more individuals both in total numbers and per capita than any other country in the world. This is currently believed to be more than two million people on any given day or more than 650 persons per 100,000 population.2 Incarceration occurs in jails, which are locally run facilities holding individuals on short sentences or those not yet convicted who are unable to afford bail before their trials (pretrial), or prisons, which are state and federally run facilities that house those with long sentences. When an incarcerated person experiences a medical emergency requiring hospitalization, they are either treated in the correctional facility or transferred to a local hospital for a higher level of care. Some hospitals are equipped with security measures similar to those of a correctional facility, with secure floors or wings dedicated solely to the care of the incarcerated. Secure units are more commonly seen in hospitals associated with prisons rather than local jails. Other hospitals house incarcerated patients in the same rooms as the public population, and thus movement is restricted by other means.3 Most commonly, this is done with a hard metal shackle resembling a handcuff with one end attached to the leg or wrist and the other end attached to the bed. Some agencies require more restraints, often requiring the use of wrist cuffs and leg cuffs concurrently for the entire duration of a patient’s hospitalization.4 In our experience, agencies apply these restraints universally, regardless of age, illness, mobility, or pretrial status.

Restraint practices are rooted in a concern for practitioner and public safety and bear merit. A patient from a correctional facility is usually guarded by just one officer in lieu of the multiple security measures at a jail or prison facility. Nonsecured hospitals have become sites of multiple escapes by incarcerated inpatients, given the lack of secured doors and the multiple movements during the admission and discharge processes.5 Furthermore, violence against hospital staff is now a focus issue in many hospitals and is no longer accepted as just “part of the job.” In several high-profile incidents, incarcerated inpatients have harmed staff, including one at our own institution, when an incarcerated patient held a makeshift weapon to a student’s throat.6

LEGAL CHALLENGES

The use of shackles during hospital visits has been challenged in US courts and routinely upheld. In one case, an incarcerated patient with renal failure received injuries after his leg edema was so severe that “at one point the shackles themselves were barely visible.”7 Though he was injured, the shackles were determined to have served a penological purpose outside of punishment, such as preventing escape, and the injuries were the result of the patient’s guards not following protocol. British courts have taken a different stance, ruling for an incarcerated patient who challenged the use of cuffs during three outpatient appointments and one inpatient admission.8 While the cuffs in the outpatient setting were deemed acceptable (as they were removed during the medical visit itself), they remained during the duration of the inpatient stay. This was deemed in violation of Title I/Article 3 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, Dignity/The right to integrity of the person. One area in US healthcare where shackling has been roundly condemned is the peripartum shackling of pregnant women. Though courts have had a mixed record to challenges, activism and advocacy have led to the banning of the practice in 23 states, though in most states significant exemptions exist.9 Through the First Step Act of 2018, the federal government banned peripartum shackling for all federal prisoners, but as most incarcerations are under state or local control, a considerable number of incarcerated pregnant women can legally be shackled during their deliveries.

RISKS OF SHACKLING

Legal and safety concerns aside, the shackling of incarcerated patients carries enormous risk. The use of medical restraints in hospitals has decreased over the past few decades, given their proven harms in increasing falls, exacerbating delirium, and increasing the risk of in-hospital death.10 There is no reason to believe that trading a soft medical restraint for a metal leg or wrist cuff would not confer the same risk. Additionally, metal law enforcement cuffs are not designed with patient safety in mind and have been known to cause specific nerve injuries, or handcuff neuropathy. This can occur when placement is too tight or when a patient struggles against them, as could happen with an agitated or delirious patient. The bar for removal, even briefly for an exam, is also much higher than that of a medical restraint, leading to a greater likelihood that certain aspects of the physical exam, such as gait or strength assessment, may not be adequately performed. In one small survey, British physicians reported often performing an exam while the patient was cuffed and with a guard in the room, despite country guidelines against both practices.11

Additionally, marginalized communities are disproportionately incarcerated and have a fraught and tenuous relationship with the healthcare system. Black patients routinely report greater mistrust than White patients in the outcomes of care and the motivations of physicians, in large part due to past and current discrimination and the medical community’s history of experimentation.12 A shackled patient may view a treating physician and hospital as complicit with the practice, rather than seeing the practice as something outside of their control. If a patient’s sole interaction with inpatient medicine involves shackling, it risks damaging whatever fragile physician-patient relationship may exist and could delay or limit care even further.

While the universal application of metal handcuffs or leg cuffs ensures low rates of escape or attacks on workers, it does so at the expense of vulnerable individuals. We have cared for an incarcerated elderly woman arrested for multiple traffic violations, a man with severe autism who slipped through the cracks of mental health diversion protocols and ended up in jail, and an arrested delirious man with severe alcohol withdrawal, all shackled with hard shackles on the wrists, legs, or in the final case, both. Safety and the rights of the vulnerable are not mutually exclusive, and we feel the following measures can protect both.

A WAY FORWARD

First, the universal application of shackles in the hospitalized incarcerated patient should end. If no alternative security measures are available for high-risk patients, correctional facilities must document their necessity as physicians and nurses are required to do for medical restraints. Hospitals should have processes in place for providers who feel unsafe with an unshackled patient or think a patient is unnecessarily shackled, and collegial discussions about shackling with law enforcement should be the norm. If safe to do so, shackles should routinely be removed for physical exams without question. Since law enforcement officials, rather than the hospitals, make the rules for shackling, this will take some degree of physician and administrative advocacy at the hospital level and legislative advocacy at the local and state levels.

Second, vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, those experiencing a mental health crisis, or others at risk for in-hospital delirium, should never be restrained with hard law enforcement cuffs. Restraint procedures should follow standard medical restraint procedures, and soft restraints should be used if at all possible. Given the high rates of psychiatric illness amongst the incarcerated and the role jails play in filling gaps in psychiatric care, medical admissions for those with mental illness are not rare occasions.

Finally, hospitals routinely taking care of an incarcerated population should seek to build secure units, a move that would dramatically reduce the need for shackling. In several cities, the primary referral hospitals for some of the largest jails in the country do not have units with the proper security to allow for freedom of movement, and thus, shackling persists. Creating secure units will take significant investment on the part of hospital and local authorities, but there is potential for decreasing costs due to consolidating supervision, which would lead to better patient outcomes given the above risks.

Advocating for the health of the incarcerated, even those who have not yet been convicted, is typically not a high priority for the general public. As inpatient physicians, we see the impact universal shackling has on some of our most vulnerable patients and should be their voice where they have none. Advocating for and implementing the above procedures will be a step toward improving patient care while maintaining safety.

1. Proctor C. Jacob Blake handcuffed to hospital bed, father says. Chicago Sun-Times. Updated August 27, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2020. chicago.suntimes.com/2020/8/27/21404463/jacob-blake-father-kenosha-police-shooting-hospital-bed-handcuffs

2. Maruschak LM, Minton TD. Correctional populations in the United States, 2017-2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics. August 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus1718.pdf

3. Huh K, Boucher A, Fehr S, McGaffey F, McKillop M, Schiff M. State prisons and the delivery of hospital care: how states set up and finance off-site care for incarcerated individuals. The Pew Charitable Trusts. July 2018. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/07/prisons-and-hospital-care_report.pdf

4. Haber LA, Erickson HP, Ranji SR, Ortiz GM, Pratt LA. Acute care for patients who are incarcerated: a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1561-1567. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3881

5. Mikow-Porto VA, Smith TA. The IHSSF 2011 Prisoner Escape Study. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2011;27(2):38-58.

6. Lezon D, Blakinger K. Inmate shot by deputy after holding medical student at Ben Taub. Houston Chronicle. October 6, 2016. Accessed December 29, 2020. https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Deputy-shoots-suspect-at-Ben-Taub-hopsital-9873972.php

7. Yearwood LT. Pregnant and shackled: why inmates are still giving birth cuffed and bound. The Guardian. January 24, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2020. theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jan/24/shackled-pregnant-women-prisoners-birth

8. Haslar v Megerman, 104 F.3d 178 (8th Cir. 1997).

9. FGP v Serco Plc and SSHD, EWHC 1804 (Admin) (2012).

10. Cleary K, Prescott K. The use of physical restraints in acute and long-term care: an updated review of the evidence, regulations, ethics, and legality. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2015;6(1):8-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAT.0000000000000005

11. Tuite H, Browne K, O’Neill D. Prisoners in general hospitals: doctors’ attitudes and practice. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):548-549. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7540.548-b

12. LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146-161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558700057001S07

1. Proctor C. Jacob Blake handcuffed to hospital bed, father says. Chicago Sun-Times. Updated August 27, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2020. chicago.suntimes.com/2020/8/27/21404463/jacob-blake-father-kenosha-police-shooting-hospital-bed-handcuffs

2. Maruschak LM, Minton TD. Correctional populations in the United States, 2017-2018. Bureau of Justice Statistics. August 2020. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus1718.pdf

3. Huh K, Boucher A, Fehr S, McGaffey F, McKillop M, Schiff M. State prisons and the delivery of hospital care: how states set up and finance off-site care for incarcerated individuals. The Pew Charitable Trusts. July 2018. Accessed September 30, 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/07/prisons-and-hospital-care_report.pdf

4. Haber LA, Erickson HP, Ranji SR, Ortiz GM, Pratt LA. Acute care for patients who are incarcerated: a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1561-1567. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3881

5. Mikow-Porto VA, Smith TA. The IHSSF 2011 Prisoner Escape Study. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2011;27(2):38-58.

6. Lezon D, Blakinger K. Inmate shot by deputy after holding medical student at Ben Taub. Houston Chronicle. October 6, 2016. Accessed December 29, 2020. https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/article/Deputy-shoots-suspect-at-Ben-Taub-hopsital-9873972.php

7. Yearwood LT. Pregnant and shackled: why inmates are still giving birth cuffed and bound. The Guardian. January 24, 2020. Accessed December 29, 2020. theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jan/24/shackled-pregnant-women-prisoners-birth

8. Haslar v Megerman, 104 F.3d 178 (8th Cir. 1997).

9. FGP v Serco Plc and SSHD, EWHC 1804 (Admin) (2012).

10. Cleary K, Prescott K. The use of physical restraints in acute and long-term care: an updated review of the evidence, regulations, ethics, and legality. J Acute Care Phys Ther. 2015;6(1):8-15. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAT.0000000000000005

11. Tuite H, Browne K, O’Neill D. Prisoners in general hospitals: doctors’ attitudes and practice. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):548-549. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7540.548-b

12. LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146-161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558700057001S07

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

AHA/ACC guidance on ethics, professionalism in cardiovascular care

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have issued a new report on medical ethics and professionalism in cardiovascular medicine.

The report addresses a variety of topics including diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; racial, ethnic and gender inequities; conflicts of interest; clinician well-being; data privacy; social justice; and modern health care delivery systems.

The 54-page report is based on the proceedings of the joint 2020 Consensus Conference on Professionalism and Ethics, held Oct. 19 and 20, 2020. It was published online May 11 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology .

The 2020 consensus conference on professionalism and ethics came at a time even more fraught than the eras of the three previous meetings on the same topics, held in 1989, 1997, and 2004, the writing group notes.

“We have seen the COVID-19 pandemic challenge the physical and economic health of the entire country, coupled with a series of national tragedies that have awakened the call for social justice,” conference cochair C. Michael Valentine, MD, said in a news release.

“There is no better time than now to review, evaluate, and take a fresh perspective on medical ethics and professionalism,” said Dr. Valentine, professor of medicine at the Heart and Vascular Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“We hope this report will provide cardiovascular professionals and health systems with the recommendations and tools they need to address conflicts of interest; racial, ethnic, and gender inequities; and improve diversity, inclusion, and wellness among our workforce,” Dr. Valentine added. “The majority of our members are now employed and must be engaged as the leaders for change in cardiovascular care.”

Road map to improve diversity, achieve allyship

The writing committee was made up of a diverse group of cardiologists, internists, and associated health care professionals and laypeople and was organized into five task forces, each addressing a specific topic: conflicts of interest; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; clinician well-being; patient autonomy, privacy, and social justice in health care; and modern health care delivery.

The report serves as a road map to achieve equity, inclusion, and belonging among cardiovascular professionals and calls for ongoing assessment of the professional culture and climate, focused on improving diversity and achieving effective allyship, the writing group says.

The report proposes continuous training to address individual, structural, and systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and ableism.

It offers recommendations for championing equity in patient care that include an annual review of practice records to look for differences in patient treatment by race, ethnicity, zip code, and primary language.

The report calls for a foundation of training in allyship and antiracism as part of medical school course requirements and experiences: A required course on social justice, race, and racism as part of the first-year curriculum; school programs and professional organizations supporting students, trainees, and members in allyship and antiracism action; and facilitating immersion and partnership with surrounding communities.

“As much as 80% of a person’s health is determined by the social and economic conditions of their environment,” consensus cochair Ivor Benjamin, MD, said in the release.

“To achieve social justice and mitigate health disparities, we must go to the margins and shift our discussions to be inclusive of populations such as rural and marginalized groups from the perspective of health equity lens for all,” said Dr. Benjamin, professor of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The report also highlights the need for psychosocial support of the cardiovascular community and recommends that health care organizations prioritize regular assessment of clinicians’ well-being and engagement.

It also recommends addressing the well-being of trainees in postgraduate training programs and calls for an ombudsman program that allows for confidential reporting of mistreatment and access to support.

The report also highlights additional opportunities to:

- improve the efficiency of health information technology, such as electronic health records, and reduce the administrative burden

- identify and assist clinicians who experience mental health conditions, , or

- emphasize patient autonomy using shared decision-making and patient-centered care that is supportive of the individual patient’s values

- increase privacy protections for patient data used in research

- maintain integrity as new ways of delivering care, such as telemedicine, team-based care approaches, and physician-owned specialty centers emerge

- perform routine audits of electronic health records to promote optimal patient care, as well as ethical medical practice

- expand and make mandatory the reporting of intellectual or associational interests in addition to relationships with industry

The report’s details and recommendations will be presented and discussed Saturday, May 15, at 8:00 AM ET, during ACC.21. The session is titled Diversity and Equity: The Means to Expand Inclusion and Belonging.

The AHA will present a live webinar and six-episode podcast series (available on demand) to highlight the report’s details, dialogue, and actionable steps for cardiovascular and health care professionals, researchers, and educators.

This research had no commercial funding. The list of 40 volunteer committee members and coauthors, including their disclosures, are listed in the original report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have issued a new report on medical ethics and professionalism in cardiovascular medicine.

The report addresses a variety of topics including diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; racial, ethnic and gender inequities; conflicts of interest; clinician well-being; data privacy; social justice; and modern health care delivery systems.

The 54-page report is based on the proceedings of the joint 2020 Consensus Conference on Professionalism and Ethics, held Oct. 19 and 20, 2020. It was published online May 11 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology .

The 2020 consensus conference on professionalism and ethics came at a time even more fraught than the eras of the three previous meetings on the same topics, held in 1989, 1997, and 2004, the writing group notes.

“We have seen the COVID-19 pandemic challenge the physical and economic health of the entire country, coupled with a series of national tragedies that have awakened the call for social justice,” conference cochair C. Michael Valentine, MD, said in a news release.

“There is no better time than now to review, evaluate, and take a fresh perspective on medical ethics and professionalism,” said Dr. Valentine, professor of medicine at the Heart and Vascular Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“We hope this report will provide cardiovascular professionals and health systems with the recommendations and tools they need to address conflicts of interest; racial, ethnic, and gender inequities; and improve diversity, inclusion, and wellness among our workforce,” Dr. Valentine added. “The majority of our members are now employed and must be engaged as the leaders for change in cardiovascular care.”

Road map to improve diversity, achieve allyship

The writing committee was made up of a diverse group of cardiologists, internists, and associated health care professionals and laypeople and was organized into five task forces, each addressing a specific topic: conflicts of interest; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; clinician well-being; patient autonomy, privacy, and social justice in health care; and modern health care delivery.

The report serves as a road map to achieve equity, inclusion, and belonging among cardiovascular professionals and calls for ongoing assessment of the professional culture and climate, focused on improving diversity and achieving effective allyship, the writing group says.

The report proposes continuous training to address individual, structural, and systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and ableism.

It offers recommendations for championing equity in patient care that include an annual review of practice records to look for differences in patient treatment by race, ethnicity, zip code, and primary language.

The report calls for a foundation of training in allyship and antiracism as part of medical school course requirements and experiences: A required course on social justice, race, and racism as part of the first-year curriculum; school programs and professional organizations supporting students, trainees, and members in allyship and antiracism action; and facilitating immersion and partnership with surrounding communities.

“As much as 80% of a person’s health is determined by the social and economic conditions of their environment,” consensus cochair Ivor Benjamin, MD, said in the release.

“To achieve social justice and mitigate health disparities, we must go to the margins and shift our discussions to be inclusive of populations such as rural and marginalized groups from the perspective of health equity lens for all,” said Dr. Benjamin, professor of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The report also highlights the need for psychosocial support of the cardiovascular community and recommends that health care organizations prioritize regular assessment of clinicians’ well-being and engagement.

It also recommends addressing the well-being of trainees in postgraduate training programs and calls for an ombudsman program that allows for confidential reporting of mistreatment and access to support.

The report also highlights additional opportunities to:

- improve the efficiency of health information technology, such as electronic health records, and reduce the administrative burden

- identify and assist clinicians who experience mental health conditions, , or

- emphasize patient autonomy using shared decision-making and patient-centered care that is supportive of the individual patient’s values

- increase privacy protections for patient data used in research

- maintain integrity as new ways of delivering care, such as telemedicine, team-based care approaches, and physician-owned specialty centers emerge

- perform routine audits of electronic health records to promote optimal patient care, as well as ethical medical practice

- expand and make mandatory the reporting of intellectual or associational interests in addition to relationships with industry

The report’s details and recommendations will be presented and discussed Saturday, May 15, at 8:00 AM ET, during ACC.21. The session is titled Diversity and Equity: The Means to Expand Inclusion and Belonging.

The AHA will present a live webinar and six-episode podcast series (available on demand) to highlight the report’s details, dialogue, and actionable steps for cardiovascular and health care professionals, researchers, and educators.

This research had no commercial funding. The list of 40 volunteer committee members and coauthors, including their disclosures, are listed in the original report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology have issued a new report on medical ethics and professionalism in cardiovascular medicine.

The report addresses a variety of topics including diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; racial, ethnic and gender inequities; conflicts of interest; clinician well-being; data privacy; social justice; and modern health care delivery systems.

The 54-page report is based on the proceedings of the joint 2020 Consensus Conference on Professionalism and Ethics, held Oct. 19 and 20, 2020. It was published online May 11 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology .

The 2020 consensus conference on professionalism and ethics came at a time even more fraught than the eras of the three previous meetings on the same topics, held in 1989, 1997, and 2004, the writing group notes.

“We have seen the COVID-19 pandemic challenge the physical and economic health of the entire country, coupled with a series of national tragedies that have awakened the call for social justice,” conference cochair C. Michael Valentine, MD, said in a news release.

“There is no better time than now to review, evaluate, and take a fresh perspective on medical ethics and professionalism,” said Dr. Valentine, professor of medicine at the Heart and Vascular Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

“We hope this report will provide cardiovascular professionals and health systems with the recommendations and tools they need to address conflicts of interest; racial, ethnic, and gender inequities; and improve diversity, inclusion, and wellness among our workforce,” Dr. Valentine added. “The majority of our members are now employed and must be engaged as the leaders for change in cardiovascular care.”

Road map to improve diversity, achieve allyship

The writing committee was made up of a diverse group of cardiologists, internists, and associated health care professionals and laypeople and was organized into five task forces, each addressing a specific topic: conflicts of interest; diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; clinician well-being; patient autonomy, privacy, and social justice in health care; and modern health care delivery.

The report serves as a road map to achieve equity, inclusion, and belonging among cardiovascular professionals and calls for ongoing assessment of the professional culture and climate, focused on improving diversity and achieving effective allyship, the writing group says.

The report proposes continuous training to address individual, structural, and systemic racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and ableism.

It offers recommendations for championing equity in patient care that include an annual review of practice records to look for differences in patient treatment by race, ethnicity, zip code, and primary language.

The report calls for a foundation of training in allyship and antiracism as part of medical school course requirements and experiences: A required course on social justice, race, and racism as part of the first-year curriculum; school programs and professional organizations supporting students, trainees, and members in allyship and antiracism action; and facilitating immersion and partnership with surrounding communities.

“As much as 80% of a person’s health is determined by the social and economic conditions of their environment,” consensus cochair Ivor Benjamin, MD, said in the release.

“To achieve social justice and mitigate health disparities, we must go to the margins and shift our discussions to be inclusive of populations such as rural and marginalized groups from the perspective of health equity lens for all,” said Dr. Benjamin, professor of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.

The report also highlights the need for psychosocial support of the cardiovascular community and recommends that health care organizations prioritize regular assessment of clinicians’ well-being and engagement.

It also recommends addressing the well-being of trainees in postgraduate training programs and calls for an ombudsman program that allows for confidential reporting of mistreatment and access to support.

The report also highlights additional opportunities to:

- improve the efficiency of health information technology, such as electronic health records, and reduce the administrative burden

- identify and assist clinicians who experience mental health conditions, , or

- emphasize patient autonomy using shared decision-making and patient-centered care that is supportive of the individual patient’s values

- increase privacy protections for patient data used in research

- maintain integrity as new ways of delivering care, such as telemedicine, team-based care approaches, and physician-owned specialty centers emerge

- perform routine audits of electronic health records to promote optimal patient care, as well as ethical medical practice

- expand and make mandatory the reporting of intellectual or associational interests in addition to relationships with industry

The report’s details and recommendations will be presented and discussed Saturday, May 15, at 8:00 AM ET, during ACC.21. The session is titled Diversity and Equity: The Means to Expand Inclusion and Belonging.

The AHA will present a live webinar and six-episode podcast series (available on demand) to highlight the report’s details, dialogue, and actionable steps for cardiovascular and health care professionals, researchers, and educators.

This research had no commercial funding. The list of 40 volunteer committee members and coauthors, including their disclosures, are listed in the original report.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

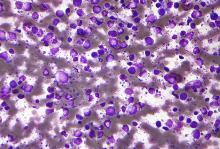

High-dose methotrexate of no CNS benefit for patients with high-risk DLBCL

Patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) have a greater than 10% risk of central nervous system (CNS) relapse, and the use of prophylactic high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) has been proposed as a preventative measure.

However, the use of prophylactic HD-MTX did not improve CNS or survival outcomes of patients with high-risk DLBCL, but instead was associated with increased toxicities, according to the results of a retrospective study by Hyehyun Jeong, MD, of University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues.

The researchers evaluated the effects of prophylactic HD-MTX on CNS relapse and survival outcomes in newly diagnosed R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone)–treated patients with high-risk DLBCL. The assessment was based on the initial treatment intent (ITT) of the physician on the use of prophylactic HD-MTX.

A total of 5,130 patients were classified into an ITT HD-MTX group and an equal number into a non-ITT HD-MTX group, according to the report, published online in Blood Advances.

Equivalent results

The study showed that the CNS relapse rate was not significantly different between the two groups, with 2-year CNS relapse rates of 12.4% and 13.9%, respectively (P = .96). Three-year progression-free survival and overall survival rates in the ITT HD-MTX and non-ITT HD-MTX groups were 62.4% vs. 64.5% (P = .94) and 71.7% vs. 71.4% (P = .7), respectively. In addition, the propensity score–matched analyses showed no significant differences in the time-to-CNS relapse, progression-free survival, or overall survival, according to the researchers.

One key concern, however, was the increase in toxicity seen in the HD-MTX group. In this study, the ITT HD-MTX group had a statistically higher incidence of grade 3/4 oral mucositis and elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, a marker for liver damage. In addition, the ITT HD-MTX group tended to have a higher incidence of elevated creatinine levels during treatment compared with the non-ITT HD-MTX group.

The HD-MTX group also showed a more common treatment delay or a dose reduction in R-CHOP, which might be attributable to toxicities related to intercalated HD-MTX treatments between R-CHOP cycles, the researchers suggested, potentially resulting in a reduced dose intensity of R-CHOP that could play a role in the lack of an observed survival benefit with additional HD-MTX.

“Another vital issue to consider is that HD-MTX treatment requires hospitalization because intensive hydration and leucovorin rescue is needed, which increases the medical costs,” the authors added.

“This real-world experience, which is unique in its scope and analytical methods, should provide insightful information on the role of HD-MTX prophylaxis to help guide current practice, given the lack of prospective clinical evidence in this patient population,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

Patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) have a greater than 10% risk of central nervous system (CNS) relapse, and the use of prophylactic high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) has been proposed as a preventative measure.

However, the use of prophylactic HD-MTX did not improve CNS or survival outcomes of patients with high-risk DLBCL, but instead was associated with increased toxicities, according to the results of a retrospective study by Hyehyun Jeong, MD, of University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues.

The researchers evaluated the effects of prophylactic HD-MTX on CNS relapse and survival outcomes in newly diagnosed R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone)–treated patients with high-risk DLBCL. The assessment was based on the initial treatment intent (ITT) of the physician on the use of prophylactic HD-MTX.

A total of 5,130 patients were classified into an ITT HD-MTX group and an equal number into a non-ITT HD-MTX group, according to the report, published online in Blood Advances.

Equivalent results

The study showed that the CNS relapse rate was not significantly different between the two groups, with 2-year CNS relapse rates of 12.4% and 13.9%, respectively (P = .96). Three-year progression-free survival and overall survival rates in the ITT HD-MTX and non-ITT HD-MTX groups were 62.4% vs. 64.5% (P = .94) and 71.7% vs. 71.4% (P = .7), respectively. In addition, the propensity score–matched analyses showed no significant differences in the time-to-CNS relapse, progression-free survival, or overall survival, according to the researchers.

One key concern, however, was the increase in toxicity seen in the HD-MTX group. In this study, the ITT HD-MTX group had a statistically higher incidence of grade 3/4 oral mucositis and elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, a marker for liver damage. In addition, the ITT HD-MTX group tended to have a higher incidence of elevated creatinine levels during treatment compared with the non-ITT HD-MTX group.

The HD-MTX group also showed a more common treatment delay or a dose reduction in R-CHOP, which might be attributable to toxicities related to intercalated HD-MTX treatments between R-CHOP cycles, the researchers suggested, potentially resulting in a reduced dose intensity of R-CHOP that could play a role in the lack of an observed survival benefit with additional HD-MTX.

“Another vital issue to consider is that HD-MTX treatment requires hospitalization because intensive hydration and leucovorin rescue is needed, which increases the medical costs,” the authors added.

“This real-world experience, which is unique in its scope and analytical methods, should provide insightful information on the role of HD-MTX prophylaxis to help guide current practice, given the lack of prospective clinical evidence in this patient population,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

Patients with high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) have a greater than 10% risk of central nervous system (CNS) relapse, and the use of prophylactic high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) has been proposed as a preventative measure.

However, the use of prophylactic HD-MTX did not improve CNS or survival outcomes of patients with high-risk DLBCL, but instead was associated with increased toxicities, according to the results of a retrospective study by Hyehyun Jeong, MD, of University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea, and colleagues.

The researchers evaluated the effects of prophylactic HD-MTX on CNS relapse and survival outcomes in newly diagnosed R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone)–treated patients with high-risk DLBCL. The assessment was based on the initial treatment intent (ITT) of the physician on the use of prophylactic HD-MTX.

A total of 5,130 patients were classified into an ITT HD-MTX group and an equal number into a non-ITT HD-MTX group, according to the report, published online in Blood Advances.

Equivalent results

The study showed that the CNS relapse rate was not significantly different between the two groups, with 2-year CNS relapse rates of 12.4% and 13.9%, respectively (P = .96). Three-year progression-free survival and overall survival rates in the ITT HD-MTX and non-ITT HD-MTX groups were 62.4% vs. 64.5% (P = .94) and 71.7% vs. 71.4% (P = .7), respectively. In addition, the propensity score–matched analyses showed no significant differences in the time-to-CNS relapse, progression-free survival, or overall survival, according to the researchers.

One key concern, however, was the increase in toxicity seen in the HD-MTX group. In this study, the ITT HD-MTX group had a statistically higher incidence of grade 3/4 oral mucositis and elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, a marker for liver damage. In addition, the ITT HD-MTX group tended to have a higher incidence of elevated creatinine levels during treatment compared with the non-ITT HD-MTX group.

The HD-MTX group also showed a more common treatment delay or a dose reduction in R-CHOP, which might be attributable to toxicities related to intercalated HD-MTX treatments between R-CHOP cycles, the researchers suggested, potentially resulting in a reduced dose intensity of R-CHOP that could play a role in the lack of an observed survival benefit with additional HD-MTX.

“Another vital issue to consider is that HD-MTX treatment requires hospitalization because intensive hydration and leucovorin rescue is needed, which increases the medical costs,” the authors added.

“This real-world experience, which is unique in its scope and analytical methods, should provide insightful information on the role of HD-MTX prophylaxis to help guide current practice, given the lack of prospective clinical evidence in this patient population,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

FROM BLOOD ADVANCES

New guidance for those fully vaccinated against COVID-19

As has been dominating the headlines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released updated public health guidance for those who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

This new guidance applies to those who are fully vaccinated as indicated by 2 weeks after the second dose in a 2-dose series or 2 weeks after a single-dose vaccine. Those who meet these criteria no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance themselves from others in both indoor and outdoor settings. For those not fully vaccinated, masking and social distancing should continue to be practiced.

The new guidance indicates that quarantine after a known exposure is no longer necessary.

Unless required by local, state, or territorial health authorities, testing is no longer required following domestic travel for fully vaccinated individuals. A negative test is still required prior to boarding an international flight to the United States and testing 3-5 days after arrival is still recommended. Self-quarantine is no longer required after international travel for fully vaccinated individuals.

The new guidance recommends that individuals who are fully vaccinated not participate in routine screening programs when feasible. Finally, if an individual has tested positive for COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, that person should isolate and not visit public or private settings for a minimum of ten days.1

Updated guidance for health care facilities

In addition to changes for the general public in all settings, the CDC updated guidance for health care facilities on April 27, 2021. These updated guidelines allow for communal dining and visitation for fully vaccinated patients and their visitors. The guidelines indicate that fully vaccinated health care personnel (HCP) do not require quarantine after exposure to patients who have tested positive for COVID-19 as long as the HCP remains asymptomatic. They should, however, continue to utilize personal protective equipment as previously recommended. HCPs are able to be in break and meeting rooms unmasked if all HCPs are vaccinated.2

There are some important caveats to these updated guidelines. They do not apply to those who have immunocompromising conditions, including those using immunosuppressant agents. They also do not apply to locations subject to federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance.

Those who work or reside in correction or detention facilities and homeless shelters are also still required to test after known exposures. Masking is still required by all travelers on all forms of public transportation into and within the United States.

Most importantly, the guidelines apply only to those who are fully vaccinated. Finally, no vaccine is perfect. As such, anyone who experiences symptoms indicative of COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, should obtain viral testing and isolate themselves from others.1,2

Pros and cons to new guidance

Both sets of updated guidelines are a great example of public health guidance that is changing as the evidence is gathered and changes. This guidance is also a welcome encouragement that the vaccines are effective at decreasing transmission of this virus that has upended our world.

These guidelines leave room for change as evidence is gathered on emerging novel variants. There are, however, a few remaining concerns.

My first concern is for those who are not yet able to be vaccinated, including children under the age of 12. For families with members who are not fully vaccinated, they may have first heard the headlines of “you do not have to mask” to then read the fine print that remains. When truly following these guidelines, many social situations in both the public and private setting should still include both masking and social distancing.

There is no clarity on how these guidelines are enforced. Within the guidance, it is clear that individuals’ privacy is of utmost importance. In the absence of knowledge, that means that the assumption should be that all are not yet vaccinated. Unless there is a way to reliably demonstrate vaccination status, it would likely still be safer to assume that there are individuals who are not fully vaccinated within the setting.

Finally, although this is great news surrounding the efficacy of the vaccine, some are concerned that local mask mandates that have already started to be lifted will be completely removed. As there is still a large portion of the population not yet fully vaccinated, it seems premature for local, state, and territorial authorities to lift these mandates.

How to continue exercising caution

With the outstanding concerns, I will continue to mask in settings, particularly indoors, where I do not definitely know that everyone is vaccinated. I will continue to do this to protect my children and my patients who are not yet vaccinated, and my patients who are immunosuppressed for whom we do not yet have enough information.

I will continue to advise my patients to be thoughtful about the risk for themselves and their families as well.

There has been more benefit to these public health measures then just decreased transmission of COVID-19. I hope that this year has reinforced within us the benefits of masking and self-isolation in the cases of any contagious illnesses.

Although I am looking forward to the opportunities to interact in person with more colleagues and friends, I think we should continue to do this with caution and thoughtfulness. We must be prepared for the possibility of vaccines having decreased efficacy against novel variants as well as eventually the possibility of waning immunity. If these should occur, we need to be prepared for additional recommendation changes and tightening of restrictions.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Public Health Recommendations for Fully Vaccinated People. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, May 13, 2021.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations in Response to COVID-19 Vaccination. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 27, 2021.

As has been dominating the headlines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released updated public health guidance for those who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

This new guidance applies to those who are fully vaccinated as indicated by 2 weeks after the second dose in a 2-dose series or 2 weeks after a single-dose vaccine. Those who meet these criteria no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance themselves from others in both indoor and outdoor settings. For those not fully vaccinated, masking and social distancing should continue to be practiced.

The new guidance indicates that quarantine after a known exposure is no longer necessary.

Unless required by local, state, or territorial health authorities, testing is no longer required following domestic travel for fully vaccinated individuals. A negative test is still required prior to boarding an international flight to the United States and testing 3-5 days after arrival is still recommended. Self-quarantine is no longer required after international travel for fully vaccinated individuals.

The new guidance recommends that individuals who are fully vaccinated not participate in routine screening programs when feasible. Finally, if an individual has tested positive for COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, that person should isolate and not visit public or private settings for a minimum of ten days.1

Updated guidance for health care facilities

In addition to changes for the general public in all settings, the CDC updated guidance for health care facilities on April 27, 2021. These updated guidelines allow for communal dining and visitation for fully vaccinated patients and their visitors. The guidelines indicate that fully vaccinated health care personnel (HCP) do not require quarantine after exposure to patients who have tested positive for COVID-19 as long as the HCP remains asymptomatic. They should, however, continue to utilize personal protective equipment as previously recommended. HCPs are able to be in break and meeting rooms unmasked if all HCPs are vaccinated.2

There are some important caveats to these updated guidelines. They do not apply to those who have immunocompromising conditions, including those using immunosuppressant agents. They also do not apply to locations subject to federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial laws, rules, and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance.

Those who work or reside in correction or detention facilities and homeless shelters are also still required to test after known exposures. Masking is still required by all travelers on all forms of public transportation into and within the United States.

Most importantly, the guidelines apply only to those who are fully vaccinated. Finally, no vaccine is perfect. As such, anyone who experiences symptoms indicative of COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, should obtain viral testing and isolate themselves from others.1,2

Pros and cons to new guidance

Both sets of updated guidelines are a great example of public health guidance that is changing as the evidence is gathered and changes. This guidance is also a welcome encouragement that the vaccines are effective at decreasing transmission of this virus that has upended our world.

These guidelines leave room for change as evidence is gathered on emerging novel variants. There are, however, a few remaining concerns.

My first concern is for those who are not yet able to be vaccinated, including children under the age of 12. For families with members who are not fully vaccinated, they may have first heard the headlines of “you do not have to mask” to then read the fine print that remains. When truly following these guidelines, many social situations in both the public and private setting should still include both masking and social distancing.

There is no clarity on how these guidelines are enforced. Within the guidance, it is clear that individuals’ privacy is of utmost importance. In the absence of knowledge, that means that the assumption should be that all are not yet vaccinated. Unless there is a way to reliably demonstrate vaccination status, it would likely still be safer to assume that there are individuals who are not fully vaccinated within the setting.

Finally, although this is great news surrounding the efficacy of the vaccine, some are concerned that local mask mandates that have already started to be lifted will be completely removed. As there is still a large portion of the population not yet fully vaccinated, it seems premature for local, state, and territorial authorities to lift these mandates.

How to continue exercising caution

With the outstanding concerns, I will continue to mask in settings, particularly indoors, where I do not definitely know that everyone is vaccinated. I will continue to do this to protect my children and my patients who are not yet vaccinated, and my patients who are immunosuppressed for whom we do not yet have enough information.

I will continue to advise my patients to be thoughtful about the risk for themselves and their families as well.

There has been more benefit to these public health measures then just decreased transmission of COVID-19. I hope that this year has reinforced within us the benefits of masking and self-isolation in the cases of any contagious illnesses.

Although I am looking forward to the opportunities to interact in person with more colleagues and friends, I think we should continue to do this with caution and thoughtfulness. We must be prepared for the possibility of vaccines having decreased efficacy against novel variants as well as eventually the possibility of waning immunity. If these should occur, we need to be prepared for additional recommendation changes and tightening of restrictions.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Public Health Recommendations for Fully Vaccinated People. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, May 13, 2021.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations in Response to COVID-19 Vaccination. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, April 27, 2021.

As has been dominating the headlines, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released updated public health guidance for those who are fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

This new guidance applies to those who are fully vaccinated as indicated by 2 weeks after the second dose in a 2-dose series or 2 weeks after a single-dose vaccine. Those who meet these criteria no longer need to wear a mask or physically distance themselves from others in both indoor and outdoor settings. For those not fully vaccinated, masking and social distancing should continue to be practiced.

The new guidance indicates that quarantine after a known exposure is no longer necessary.

Unless required by local, state, or territorial health authorities, testing is no longer required following domestic travel for fully vaccinated individuals. A negative test is still required prior to boarding an international flight to the United States and testing 3-5 days after arrival is still recommended. Self-quarantine is no longer required after international travel for fully vaccinated individuals.

The new guidance recommends that individuals who are fully vaccinated not participate in routine screening programs when feasible. Finally, if an individual has tested positive for COVID-19, regardless of vaccination status, that person should isolate and not visit public or private settings for a minimum of ten days.1

Updated guidance for health care facilities

In addition to changes for the general public in all settings, the CDC updated guidance for health care facilities on April 27, 2021. These updated guidelines allow for communal dining and visitation for fully vaccinated patients and their visitors. The guidelines indicate that fully vaccinated health care personnel (HCP) do not require quarantine after exposure to patients who have tested positive for COVID-19 as long as the HCP remains asymptomatic. They should, however, continue to utilize personal protective equipment as previously recommended. HCPs are able to be in break and meeting rooms unmasked if all HCPs are vaccinated.2