User login

Implementing Trustworthy AI in VA High Reliability Health Care Organizations

Artificial intelligence (AI) has lagged in health care but has considerable potential to improve quality, safety, clinician experience, and access to care. It is being tested in areas like billing, hospital operations, and preventing adverse events (eg, sepsis mortality) with some early success. However, there are still many barriers preventing the widespread use of AI, such as data problems, mismatched rewards, and workplace obstacles. Innovative projects, partnerships, better rewards, and more investment could remove barriers. Implemented reliably and safely, AI can add to what clinicians know, help them work faster, cut costs, and, most importantly, improve patient care.1

AI can potentially bring several clinical benefits, such as reducing the administrative strain on clinicians and granting them more time for direct patient care. It can also improve diagnostic accuracy by analyzing patient data and diagnostic images, providing differential diagnoses, and increasing access to care by providing medical information and essential online services to patients.2

High Reliability Organizations

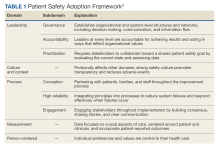

High reliability health care organizations have considerable experience safely launching new programs. For example, the Patient Safety Adoption Framework gives practical tips for smoothly rolling out safety initiatives (Table 1). Developed with experts and diverse views, this framework has 5 key areas: leadership, culture and context, process, measurement, and person-centeredness. These address adoption problems, guide leaders step-by-step, and focus on leadership buy-in, safety culture, cooperation, and local customization. Checklists and tools make it systematic to go from ideas to action on patient safety.3

Leadership involves establishing organizational commitment behind new safety programs. This visible commitment signals importance and priorities to others. Leaders model desired behaviors and language around safety, allocate resources, remove obstacles, and keep initiatives energized over time through consistent messaging.4 Culture and context recognizes that safety culture differs across units and facilities. Local input tailors programs to fit and examines strengths to build on, like psychological safety. Surveys gauge the existing culture and its need for change. Process details how to plan, design, test, implement, and improve new safety practices and provides a phased roadmap from idea to results. Measurement collects data to drive improvement and show impact. Metrics track progress and allow benchmarking. Person-centeredness puts patients first in safety efforts through participation, education, and transparency.

The Veterans Health Administration piloted a comprehensive high reliability hospital (HRH) model. Over 3 years, the Veterans Health Administration focused on leadership, culture, and process improvement at a hospital. After initiating the model, the pilot hospital improved its safety culture, reported more minor safety issues, and reduced deaths and complications better than other hospitals. The high-reliability approach successfully instilled principles and improved culture and outcomes. The HRH model is set to be expanded to 18 more US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) sites for further evaluation across diverse settings.5

Trustworthy AI Framework

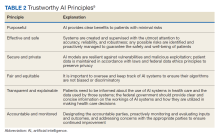

AI systems are growing more powerful and widespread, including in health care. Unfortunately, irresponsible AI can introduce new harm. ChatGPT and other large language models, for example, sometimes are known to provide erroneous information in a compelling way. Clinicians and patients who use such programs can act on such information, which would lead to unforeseen negative consequences. Several frameworks on ethical AI have come from governmental groups.6-9 In 2023, the VA National AI Institute suggested a Trustworthy AI Framework based on core principles tailored for federal health care. The framework has 6 key principles: purposeful, effective and safe, secure and private, fair and equitable, transparent and explainable, and accountable and monitored (Table 2).10

First, AI must clearly help veterans while minimizing risks. To ensure purpose, the VA will assess patient and clinician needs and design AI that targets meaningful problems to avoid scope creep or feature bloat. For example, adding new features to the AI software after release can clutter and complicate the interface, making it difficult to use. Rigorous testing will confirm that AI meets intent prior to deployment. Second, AI is designed and checked for effectiveness, safety, and reliability. The VA pledges to monitor AI’s impact to ensure it performs as expected without unintended consequences. Algorithms will be stress tested across representative datasets and approval processes will screen for safety issues. Third, AI models are secured from vulnerabilities and misuse. Technical controls will prevent unauthorized access or changes to AI systems. Audits will check for appropriate internal usage per policies. Continual patches and upgrades will maintain security. Fourth, the VA manages AI for fairness, avoiding bias. They will proactively assess datasets and algorithms for potential biases based on protected attributes like race, gender, or age. Biased outputs will be addressed through techniques such as data augmentation, reweighting, and algorithm tweaks. Fifth, transparency explains AI’s role in care. Documentation will detail an AI system’s data sources, methodology, testing, limitations, and integration with clinical workflows. Clinicians and patients will receive education on interpreting AI outputs. Finally, the VA pledges to closely monitor AI systems to sustain trust. The VA will establish oversight processes to quickly identify any declines in reliability or unfair impacts on subgroups. AI models will be retrained as needed based on incoming data patterns.

Each Trustworthy AI Framework principle connects to others in existing frameworks. The purpose principle aligns with human-centric AI focused on benefits. Effectiveness and safety link to technical robustness and risk management principles. Security maps to privacy protection principles. Fairness connects to principles of avoiding bias and discrimination. Transparency corresponds with accountable and explainable AI. Monitoring and accountability tie back to governance principles. Overall, the VA framework aims to guide ethical AI based on context. It offers a model for managing risks and building trust in health care AI.

Combining VA principles with high-reliability safety principles can ensure that AI benefits veterans. The leadership and culture aspects will drive commitment to trustworthy AI practices. Leaders will communicate the importance of responsible AI through words and actions. Culture surveys can assess baseline awareness of AI ethics issues to target education. AI security and fairness will be emphasized as safety critical. The process aspect will institute policies and procedures to uphold AI principles through the project lifecycle. For example, structured testing processes will validate safety. Measurement will collect data on principles like transparency and fairness. Dashboards can track metrics like explainability and biases. A patient-centered approach will incorporate veteran perspectives on AI through participatory design and advisory councils. They can give input on AI explainability and potential biases based on their diverse backgrounds.

Conclusions

Joint principles will lead to successful AI that improves care while proactively managing risks. Involve leaders to stress the necessity of eliminating biases. Build security into the AI development process. Co-design AI transparency features with end users. Closely monitor the impact of AI across safety, fairness, and other principles. Adhering to both Trustworthy AI and high reliability organizations principles will earn veterans’ confidence. Health care organizations like the VA can integrate ethical AI safely via established frameworks. With responsible design and implementation, AI’s potential to enhance care quality, safety, and access can be realized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Joshua Mueller, Theo Tiffney, John Zachary, and Gil Alterovitz for their excellent work creating the VA Trustworthy Principles. This material is the result of work supported by resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

1. Sahni NR, Carrus B. Artificial intelligence in U.S. health care delivery. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(4):348-358. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2204673

2. Borkowski AA, Jakey CE, Mastorides SM, et al. Applications of ChatGPT and large language models in medicine and health care: benefits and pitfalls. Fed Pract. 2023;40(6):170-173. doi:10.12788/fp.0386

3. Moyal-Smith R, Margo J, Maloney FL, et al. The patient safety adoption framework: a practical framework to bridge the know-do gap. J Patient Saf. 2023;19(4):243-248. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001118

4. Isaacks DB, Anderson TM, Moore SC, Patterson W, Govindan S. High reliability organization principles improve VA workplace burnout: the Truman THRIVE2 model. Am J Med Qual. 2021;36(6):422-428. doi:10.1097/01.JMQ.0000735516.35323.97

5. Sculli GL, Pendley-Louis R, Neily J, et al. A high-reliability organization framework for health care: a multiyear implementation strategy and associated outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):64-70. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000788

6. National Institute of Standards and Technology. AI risk management framework. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://www.nist.gov/itl/ai-risk-management-framework

7. Executive Office of the President, Office of Science and Technology Policy. Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights

8. Executive Office of the President. Executive Order 13960: promoting the use of trustworthy artificial intelligence in the federal government. Fed Regist. 2020;89(236):78939-78943.

9. Biden JR. Executive Order on the safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of artificial intelligence. Published October 30, 2023. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Trustworthy AI. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://department.va.gov/ai/trustworthy/

Artificial intelligence (AI) has lagged in health care but has considerable potential to improve quality, safety, clinician experience, and access to care. It is being tested in areas like billing, hospital operations, and preventing adverse events (eg, sepsis mortality) with some early success. However, there are still many barriers preventing the widespread use of AI, such as data problems, mismatched rewards, and workplace obstacles. Innovative projects, partnerships, better rewards, and more investment could remove barriers. Implemented reliably and safely, AI can add to what clinicians know, help them work faster, cut costs, and, most importantly, improve patient care.1

AI can potentially bring several clinical benefits, such as reducing the administrative strain on clinicians and granting them more time for direct patient care. It can also improve diagnostic accuracy by analyzing patient data and diagnostic images, providing differential diagnoses, and increasing access to care by providing medical information and essential online services to patients.2

High Reliability Organizations

High reliability health care organizations have considerable experience safely launching new programs. For example, the Patient Safety Adoption Framework gives practical tips for smoothly rolling out safety initiatives (Table 1). Developed with experts and diverse views, this framework has 5 key areas: leadership, culture and context, process, measurement, and person-centeredness. These address adoption problems, guide leaders step-by-step, and focus on leadership buy-in, safety culture, cooperation, and local customization. Checklists and tools make it systematic to go from ideas to action on patient safety.3

Leadership involves establishing organizational commitment behind new safety programs. This visible commitment signals importance and priorities to others. Leaders model desired behaviors and language around safety, allocate resources, remove obstacles, and keep initiatives energized over time through consistent messaging.4 Culture and context recognizes that safety culture differs across units and facilities. Local input tailors programs to fit and examines strengths to build on, like psychological safety. Surveys gauge the existing culture and its need for change. Process details how to plan, design, test, implement, and improve new safety practices and provides a phased roadmap from idea to results. Measurement collects data to drive improvement and show impact. Metrics track progress and allow benchmarking. Person-centeredness puts patients first in safety efforts through participation, education, and transparency.

The Veterans Health Administration piloted a comprehensive high reliability hospital (HRH) model. Over 3 years, the Veterans Health Administration focused on leadership, culture, and process improvement at a hospital. After initiating the model, the pilot hospital improved its safety culture, reported more minor safety issues, and reduced deaths and complications better than other hospitals. The high-reliability approach successfully instilled principles and improved culture and outcomes. The HRH model is set to be expanded to 18 more US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) sites for further evaluation across diverse settings.5

Trustworthy AI Framework

AI systems are growing more powerful and widespread, including in health care. Unfortunately, irresponsible AI can introduce new harm. ChatGPT and other large language models, for example, sometimes are known to provide erroneous information in a compelling way. Clinicians and patients who use such programs can act on such information, which would lead to unforeseen negative consequences. Several frameworks on ethical AI have come from governmental groups.6-9 In 2023, the VA National AI Institute suggested a Trustworthy AI Framework based on core principles tailored for federal health care. The framework has 6 key principles: purposeful, effective and safe, secure and private, fair and equitable, transparent and explainable, and accountable and monitored (Table 2).10

First, AI must clearly help veterans while minimizing risks. To ensure purpose, the VA will assess patient and clinician needs and design AI that targets meaningful problems to avoid scope creep or feature bloat. For example, adding new features to the AI software after release can clutter and complicate the interface, making it difficult to use. Rigorous testing will confirm that AI meets intent prior to deployment. Second, AI is designed and checked for effectiveness, safety, and reliability. The VA pledges to monitor AI’s impact to ensure it performs as expected without unintended consequences. Algorithms will be stress tested across representative datasets and approval processes will screen for safety issues. Third, AI models are secured from vulnerabilities and misuse. Technical controls will prevent unauthorized access or changes to AI systems. Audits will check for appropriate internal usage per policies. Continual patches and upgrades will maintain security. Fourth, the VA manages AI for fairness, avoiding bias. They will proactively assess datasets and algorithms for potential biases based on protected attributes like race, gender, or age. Biased outputs will be addressed through techniques such as data augmentation, reweighting, and algorithm tweaks. Fifth, transparency explains AI’s role in care. Documentation will detail an AI system’s data sources, methodology, testing, limitations, and integration with clinical workflows. Clinicians and patients will receive education on interpreting AI outputs. Finally, the VA pledges to closely monitor AI systems to sustain trust. The VA will establish oversight processes to quickly identify any declines in reliability or unfair impacts on subgroups. AI models will be retrained as needed based on incoming data patterns.

Each Trustworthy AI Framework principle connects to others in existing frameworks. The purpose principle aligns with human-centric AI focused on benefits. Effectiveness and safety link to technical robustness and risk management principles. Security maps to privacy protection principles. Fairness connects to principles of avoiding bias and discrimination. Transparency corresponds with accountable and explainable AI. Monitoring and accountability tie back to governance principles. Overall, the VA framework aims to guide ethical AI based on context. It offers a model for managing risks and building trust in health care AI.

Combining VA principles with high-reliability safety principles can ensure that AI benefits veterans. The leadership and culture aspects will drive commitment to trustworthy AI practices. Leaders will communicate the importance of responsible AI through words and actions. Culture surveys can assess baseline awareness of AI ethics issues to target education. AI security and fairness will be emphasized as safety critical. The process aspect will institute policies and procedures to uphold AI principles through the project lifecycle. For example, structured testing processes will validate safety. Measurement will collect data on principles like transparency and fairness. Dashboards can track metrics like explainability and biases. A patient-centered approach will incorporate veteran perspectives on AI through participatory design and advisory councils. They can give input on AI explainability and potential biases based on their diverse backgrounds.

Conclusions

Joint principles will lead to successful AI that improves care while proactively managing risks. Involve leaders to stress the necessity of eliminating biases. Build security into the AI development process. Co-design AI transparency features with end users. Closely monitor the impact of AI across safety, fairness, and other principles. Adhering to both Trustworthy AI and high reliability organizations principles will earn veterans’ confidence. Health care organizations like the VA can integrate ethical AI safely via established frameworks. With responsible design and implementation, AI’s potential to enhance care quality, safety, and access can be realized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Joshua Mueller, Theo Tiffney, John Zachary, and Gil Alterovitz for their excellent work creating the VA Trustworthy Principles. This material is the result of work supported by resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has lagged in health care but has considerable potential to improve quality, safety, clinician experience, and access to care. It is being tested in areas like billing, hospital operations, and preventing adverse events (eg, sepsis mortality) with some early success. However, there are still many barriers preventing the widespread use of AI, such as data problems, mismatched rewards, and workplace obstacles. Innovative projects, partnerships, better rewards, and more investment could remove barriers. Implemented reliably and safely, AI can add to what clinicians know, help them work faster, cut costs, and, most importantly, improve patient care.1

AI can potentially bring several clinical benefits, such as reducing the administrative strain on clinicians and granting them more time for direct patient care. It can also improve diagnostic accuracy by analyzing patient data and diagnostic images, providing differential diagnoses, and increasing access to care by providing medical information and essential online services to patients.2

High Reliability Organizations

High reliability health care organizations have considerable experience safely launching new programs. For example, the Patient Safety Adoption Framework gives practical tips for smoothly rolling out safety initiatives (Table 1). Developed with experts and diverse views, this framework has 5 key areas: leadership, culture and context, process, measurement, and person-centeredness. These address adoption problems, guide leaders step-by-step, and focus on leadership buy-in, safety culture, cooperation, and local customization. Checklists and tools make it systematic to go from ideas to action on patient safety.3

Leadership involves establishing organizational commitment behind new safety programs. This visible commitment signals importance and priorities to others. Leaders model desired behaviors and language around safety, allocate resources, remove obstacles, and keep initiatives energized over time through consistent messaging.4 Culture and context recognizes that safety culture differs across units and facilities. Local input tailors programs to fit and examines strengths to build on, like psychological safety. Surveys gauge the existing culture and its need for change. Process details how to plan, design, test, implement, and improve new safety practices and provides a phased roadmap from idea to results. Measurement collects data to drive improvement and show impact. Metrics track progress and allow benchmarking. Person-centeredness puts patients first in safety efforts through participation, education, and transparency.

The Veterans Health Administration piloted a comprehensive high reliability hospital (HRH) model. Over 3 years, the Veterans Health Administration focused on leadership, culture, and process improvement at a hospital. After initiating the model, the pilot hospital improved its safety culture, reported more minor safety issues, and reduced deaths and complications better than other hospitals. The high-reliability approach successfully instilled principles and improved culture and outcomes. The HRH model is set to be expanded to 18 more US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) sites for further evaluation across diverse settings.5

Trustworthy AI Framework

AI systems are growing more powerful and widespread, including in health care. Unfortunately, irresponsible AI can introduce new harm. ChatGPT and other large language models, for example, sometimes are known to provide erroneous information in a compelling way. Clinicians and patients who use such programs can act on such information, which would lead to unforeseen negative consequences. Several frameworks on ethical AI have come from governmental groups.6-9 In 2023, the VA National AI Institute suggested a Trustworthy AI Framework based on core principles tailored for federal health care. The framework has 6 key principles: purposeful, effective and safe, secure and private, fair and equitable, transparent and explainable, and accountable and monitored (Table 2).10

First, AI must clearly help veterans while minimizing risks. To ensure purpose, the VA will assess patient and clinician needs and design AI that targets meaningful problems to avoid scope creep or feature bloat. For example, adding new features to the AI software after release can clutter and complicate the interface, making it difficult to use. Rigorous testing will confirm that AI meets intent prior to deployment. Second, AI is designed and checked for effectiveness, safety, and reliability. The VA pledges to monitor AI’s impact to ensure it performs as expected without unintended consequences. Algorithms will be stress tested across representative datasets and approval processes will screen for safety issues. Third, AI models are secured from vulnerabilities and misuse. Technical controls will prevent unauthorized access or changes to AI systems. Audits will check for appropriate internal usage per policies. Continual patches and upgrades will maintain security. Fourth, the VA manages AI for fairness, avoiding bias. They will proactively assess datasets and algorithms for potential biases based on protected attributes like race, gender, or age. Biased outputs will be addressed through techniques such as data augmentation, reweighting, and algorithm tweaks. Fifth, transparency explains AI’s role in care. Documentation will detail an AI system’s data sources, methodology, testing, limitations, and integration with clinical workflows. Clinicians and patients will receive education on interpreting AI outputs. Finally, the VA pledges to closely monitor AI systems to sustain trust. The VA will establish oversight processes to quickly identify any declines in reliability or unfair impacts on subgroups. AI models will be retrained as needed based on incoming data patterns.

Each Trustworthy AI Framework principle connects to others in existing frameworks. The purpose principle aligns with human-centric AI focused on benefits. Effectiveness and safety link to technical robustness and risk management principles. Security maps to privacy protection principles. Fairness connects to principles of avoiding bias and discrimination. Transparency corresponds with accountable and explainable AI. Monitoring and accountability tie back to governance principles. Overall, the VA framework aims to guide ethical AI based on context. It offers a model for managing risks and building trust in health care AI.

Combining VA principles with high-reliability safety principles can ensure that AI benefits veterans. The leadership and culture aspects will drive commitment to trustworthy AI practices. Leaders will communicate the importance of responsible AI through words and actions. Culture surveys can assess baseline awareness of AI ethics issues to target education. AI security and fairness will be emphasized as safety critical. The process aspect will institute policies and procedures to uphold AI principles through the project lifecycle. For example, structured testing processes will validate safety. Measurement will collect data on principles like transparency and fairness. Dashboards can track metrics like explainability and biases. A patient-centered approach will incorporate veteran perspectives on AI through participatory design and advisory councils. They can give input on AI explainability and potential biases based on their diverse backgrounds.

Conclusions

Joint principles will lead to successful AI that improves care while proactively managing risks. Involve leaders to stress the necessity of eliminating biases. Build security into the AI development process. Co-design AI transparency features with end users. Closely monitor the impact of AI across safety, fairness, and other principles. Adhering to both Trustworthy AI and high reliability organizations principles will earn veterans’ confidence. Health care organizations like the VA can integrate ethical AI safely via established frameworks. With responsible design and implementation, AI’s potential to enhance care quality, safety, and access can be realized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Joshua Mueller, Theo Tiffney, John Zachary, and Gil Alterovitz for their excellent work creating the VA Trustworthy Principles. This material is the result of work supported by resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

1. Sahni NR, Carrus B. Artificial intelligence in U.S. health care delivery. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(4):348-358. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2204673

2. Borkowski AA, Jakey CE, Mastorides SM, et al. Applications of ChatGPT and large language models in medicine and health care: benefits and pitfalls. Fed Pract. 2023;40(6):170-173. doi:10.12788/fp.0386

3. Moyal-Smith R, Margo J, Maloney FL, et al. The patient safety adoption framework: a practical framework to bridge the know-do gap. J Patient Saf. 2023;19(4):243-248. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001118

4. Isaacks DB, Anderson TM, Moore SC, Patterson W, Govindan S. High reliability organization principles improve VA workplace burnout: the Truman THRIVE2 model. Am J Med Qual. 2021;36(6):422-428. doi:10.1097/01.JMQ.0000735516.35323.97

5. Sculli GL, Pendley-Louis R, Neily J, et al. A high-reliability organization framework for health care: a multiyear implementation strategy and associated outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):64-70. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000788

6. National Institute of Standards and Technology. AI risk management framework. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://www.nist.gov/itl/ai-risk-management-framework

7. Executive Office of the President, Office of Science and Technology Policy. Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights

8. Executive Office of the President. Executive Order 13960: promoting the use of trustworthy artificial intelligence in the federal government. Fed Regist. 2020;89(236):78939-78943.

9. Biden JR. Executive Order on the safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of artificial intelligence. Published October 30, 2023. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Trustworthy AI. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://department.va.gov/ai/trustworthy/

1. Sahni NR, Carrus B. Artificial intelligence in U.S. health care delivery. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(4):348-358. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2204673

2. Borkowski AA, Jakey CE, Mastorides SM, et al. Applications of ChatGPT and large language models in medicine and health care: benefits and pitfalls. Fed Pract. 2023;40(6):170-173. doi:10.12788/fp.0386

3. Moyal-Smith R, Margo J, Maloney FL, et al. The patient safety adoption framework: a practical framework to bridge the know-do gap. J Patient Saf. 2023;19(4):243-248. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001118

4. Isaacks DB, Anderson TM, Moore SC, Patterson W, Govindan S. High reliability organization principles improve VA workplace burnout: the Truman THRIVE2 model. Am J Med Qual. 2021;36(6):422-428. doi:10.1097/01.JMQ.0000735516.35323.97

5. Sculli GL, Pendley-Louis R, Neily J, et al. A high-reliability organization framework for health care: a multiyear implementation strategy and associated outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):64-70. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000788

6. National Institute of Standards and Technology. AI risk management framework. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://www.nist.gov/itl/ai-risk-management-framework

7. Executive Office of the President, Office of Science and Technology Policy. Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights

8. Executive Office of the President. Executive Order 13960: promoting the use of trustworthy artificial intelligence in the federal government. Fed Regist. 2020;89(236):78939-78943.

9. Biden JR. Executive Order on the safe, secure, and trustworthy development and use of artificial intelligence. Published October 30, 2023. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/

10. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Trustworthy AI. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://department.va.gov/ai/trustworthy/

Most Americans Believe Bariatric Surgery Is Shortcut, Should Be ‘Last Resort’: Survey

Most Americans’ views about obesity and bariatric surgery are colored by stigmas, according to a new survey from the healthcare system at Orlando Health.

For example, most Americans believe that weight loss surgery should be pursued only as a last resort and that bariatric surgery is a shortcut to shedding pounds, the survey found.

Common stigmas could be deterring people who qualify for bariatric surgery from pursuing it, according to Orlando Health, located in Florida.

“Bariatric surgery is by no means an easy way out. If you have the courage to ask for help and commit to doing the hard work of changing your diet and improving your life, you’re a champion in my book,” said Andre Teixeira, MD, medical director and bariatric surgeon at Orlando Health Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery Institute, Orlando, Florida.

“Surgery is simply a tool to jumpstart that change,” he said. “After surgery, it is up to the patient to learn how to eat well, implement exercise into their routine, and shift their mindset to maintain their health for the rest of their lives.”

The survey results were published in January by Orlando Health.

Surveying Americans

The national survey, conducted for Orlando Health by the market research firm Ipsos in early November 2023, asked 1017 US adults whether they agreed or disagreed with several statements about weight loss and bariatric surgery. The statements and responses are as follows:

- “Weight loss surgery is a shortcut to shedding pounds” — 60% strongly or somewhat agreed, 38% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to answer.

- “Weight loss surgery is cosmetic and mainly impacts appearance” — 37% strongly or somewhat agreed, 61% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

- “Exercise and diet should be enough for weight loss” — 61% strongly or somewhat agreed, 37% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

- “Weight loss surgery should only be pursued as a last resort” — 79% strongly or somewhat agreed, 19% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to answer.

- “Surgery should be more socially accepted as a way to lose weight” — 46% strongly or somewhat agreed, 52% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

Men’s responses indicated that they are more likely to have negative views toward weight loss surgery than women. For example, 66% of men vs 54% of women respondents see weight loss surgery as a shortcut to losing weight. Conversely, 42% of men vs 50% of women said that surgery should be a more socially accepted weight loss method.

Opinions that might interfere with the willingness to have weight loss surgery were apparent among people with obesity. The survey found that 65% of respondents with obesity and 59% with extreme obesity view surgery as a shortcut. Eighty-two percent of respondents with obesity and 68% with extreme obesity see surgery as a last resort.

At the end of 2022, the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders updated their guidelines for metabolic and bariatric surgery for the first time since 1991, with the aim of expanding access to surgery, Orlando Health noted. However, only 1% of those who are clinically eligible end up undergoing weight loss surgery, even with advancements in laparoscopic and robotic techniques that have made it safer and less invasive, the health system added.

“Because of the stigma around obesity and bariatric surgery, so many of my patients feel defeated if they can’t lose weight on their own,” said Muhammad Ghanem, MD, a bariatric surgeon at Orlando Health.

“But when I tell them obesity is a disease and that many of its causes are outside of their control, you can see their relief,” he said. “They often even shed a tear because they’ve struggled with their weight all their lives and finally have some validation.”

Individualizing Treatment

Obesity treatment plans should be tailored to patients on the basis of individual factors such as body mass index, existing medical conditions, and family history, Dr. Teixeira said.

Besides bariatric surgery, patients also may consider options such as counseling, lifestyle changes, and medications including the latest weight loss drugs, he added.

The clinical approach to obesity treatment has evolved, said Miguel Burch, MD, director of general surgery and chief of minimally invasive and gastrointestinal surgery at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, California, who was not involved in the survey.

“At one point in my career, I could say the only proven durable treatment for obesity is weight loss surgery. This was in the context of patients who were morbidly obese requiring risk reduction, not for a year or two but for decades, and not for 10-20 pounds but for 40-60 pounds of weight loss,” said Dr. Burch, who also directs the bariatric surgery program at Torrance Memorial Medical Center, Torrance, California.

“That was a previous era. We are now in a new one with the weight loss drugs,” Dr. Burch said. “In fact, it’s wonderful to have the opportunity to serve so many patients with an option other than just surgery.”

Still, Dr. Burch added, “we have to change the way we look at obesity management as being either surgery or medicine and start thinking about it more as a multidisciplinary approach to a chronic and potentially relapsing disease.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Most Americans’ views about obesity and bariatric surgery are colored by stigmas, according to a new survey from the healthcare system at Orlando Health.

For example, most Americans believe that weight loss surgery should be pursued only as a last resort and that bariatric surgery is a shortcut to shedding pounds, the survey found.

Common stigmas could be deterring people who qualify for bariatric surgery from pursuing it, according to Orlando Health, located in Florida.

“Bariatric surgery is by no means an easy way out. If you have the courage to ask for help and commit to doing the hard work of changing your diet and improving your life, you’re a champion in my book,” said Andre Teixeira, MD, medical director and bariatric surgeon at Orlando Health Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery Institute, Orlando, Florida.

“Surgery is simply a tool to jumpstart that change,” he said. “After surgery, it is up to the patient to learn how to eat well, implement exercise into their routine, and shift their mindset to maintain their health for the rest of their lives.”

The survey results were published in January by Orlando Health.

Surveying Americans

The national survey, conducted for Orlando Health by the market research firm Ipsos in early November 2023, asked 1017 US adults whether they agreed or disagreed with several statements about weight loss and bariatric surgery. The statements and responses are as follows:

- “Weight loss surgery is a shortcut to shedding pounds” — 60% strongly or somewhat agreed, 38% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to answer.

- “Weight loss surgery is cosmetic and mainly impacts appearance” — 37% strongly or somewhat agreed, 61% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

- “Exercise and diet should be enough for weight loss” — 61% strongly or somewhat agreed, 37% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

- “Weight loss surgery should only be pursued as a last resort” — 79% strongly or somewhat agreed, 19% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to answer.

- “Surgery should be more socially accepted as a way to lose weight” — 46% strongly or somewhat agreed, 52% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

Men’s responses indicated that they are more likely to have negative views toward weight loss surgery than women. For example, 66% of men vs 54% of women respondents see weight loss surgery as a shortcut to losing weight. Conversely, 42% of men vs 50% of women said that surgery should be a more socially accepted weight loss method.

Opinions that might interfere with the willingness to have weight loss surgery were apparent among people with obesity. The survey found that 65% of respondents with obesity and 59% with extreme obesity view surgery as a shortcut. Eighty-two percent of respondents with obesity and 68% with extreme obesity see surgery as a last resort.

At the end of 2022, the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders updated their guidelines for metabolic and bariatric surgery for the first time since 1991, with the aim of expanding access to surgery, Orlando Health noted. However, only 1% of those who are clinically eligible end up undergoing weight loss surgery, even with advancements in laparoscopic and robotic techniques that have made it safer and less invasive, the health system added.

“Because of the stigma around obesity and bariatric surgery, so many of my patients feel defeated if they can’t lose weight on their own,” said Muhammad Ghanem, MD, a bariatric surgeon at Orlando Health.

“But when I tell them obesity is a disease and that many of its causes are outside of their control, you can see their relief,” he said. “They often even shed a tear because they’ve struggled with their weight all their lives and finally have some validation.”

Individualizing Treatment

Obesity treatment plans should be tailored to patients on the basis of individual factors such as body mass index, existing medical conditions, and family history, Dr. Teixeira said.

Besides bariatric surgery, patients also may consider options such as counseling, lifestyle changes, and medications including the latest weight loss drugs, he added.

The clinical approach to obesity treatment has evolved, said Miguel Burch, MD, director of general surgery and chief of minimally invasive and gastrointestinal surgery at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, California, who was not involved in the survey.

“At one point in my career, I could say the only proven durable treatment for obesity is weight loss surgery. This was in the context of patients who were morbidly obese requiring risk reduction, not for a year or two but for decades, and not for 10-20 pounds but for 40-60 pounds of weight loss,” said Dr. Burch, who also directs the bariatric surgery program at Torrance Memorial Medical Center, Torrance, California.

“That was a previous era. We are now in a new one with the weight loss drugs,” Dr. Burch said. “In fact, it’s wonderful to have the opportunity to serve so many patients with an option other than just surgery.”

Still, Dr. Burch added, “we have to change the way we look at obesity management as being either surgery or medicine and start thinking about it more as a multidisciplinary approach to a chronic and potentially relapsing disease.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Most Americans’ views about obesity and bariatric surgery are colored by stigmas, according to a new survey from the healthcare system at Orlando Health.

For example, most Americans believe that weight loss surgery should be pursued only as a last resort and that bariatric surgery is a shortcut to shedding pounds, the survey found.

Common stigmas could be deterring people who qualify for bariatric surgery from pursuing it, according to Orlando Health, located in Florida.

“Bariatric surgery is by no means an easy way out. If you have the courage to ask for help and commit to doing the hard work of changing your diet and improving your life, you’re a champion in my book,” said Andre Teixeira, MD, medical director and bariatric surgeon at Orlando Health Weight Loss and Bariatric Surgery Institute, Orlando, Florida.

“Surgery is simply a tool to jumpstart that change,” he said. “After surgery, it is up to the patient to learn how to eat well, implement exercise into their routine, and shift their mindset to maintain their health for the rest of their lives.”

The survey results were published in January by Orlando Health.

Surveying Americans

The national survey, conducted for Orlando Health by the market research firm Ipsos in early November 2023, asked 1017 US adults whether they agreed or disagreed with several statements about weight loss and bariatric surgery. The statements and responses are as follows:

- “Weight loss surgery is a shortcut to shedding pounds” — 60% strongly or somewhat agreed, 38% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to answer.

- “Weight loss surgery is cosmetic and mainly impacts appearance” — 37% strongly or somewhat agreed, 61% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

- “Exercise and diet should be enough for weight loss” — 61% strongly or somewhat agreed, 37% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

- “Weight loss surgery should only be pursued as a last resort” — 79% strongly or somewhat agreed, 19% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to answer.

- “Surgery should be more socially accepted as a way to lose weight” — 46% strongly or somewhat agreed, 52% strongly or somewhat disagreed, and the remainder declined to respond.

Men’s responses indicated that they are more likely to have negative views toward weight loss surgery than women. For example, 66% of men vs 54% of women respondents see weight loss surgery as a shortcut to losing weight. Conversely, 42% of men vs 50% of women said that surgery should be a more socially accepted weight loss method.

Opinions that might interfere with the willingness to have weight loss surgery were apparent among people with obesity. The survey found that 65% of respondents with obesity and 59% with extreme obesity view surgery as a shortcut. Eighty-two percent of respondents with obesity and 68% with extreme obesity see surgery as a last resort.

At the end of 2022, the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders updated their guidelines for metabolic and bariatric surgery for the first time since 1991, with the aim of expanding access to surgery, Orlando Health noted. However, only 1% of those who are clinically eligible end up undergoing weight loss surgery, even with advancements in laparoscopic and robotic techniques that have made it safer and less invasive, the health system added.

“Because of the stigma around obesity and bariatric surgery, so many of my patients feel defeated if they can’t lose weight on their own,” said Muhammad Ghanem, MD, a bariatric surgeon at Orlando Health.

“But when I tell them obesity is a disease and that many of its causes are outside of their control, you can see their relief,” he said. “They often even shed a tear because they’ve struggled with their weight all their lives and finally have some validation.”

Individualizing Treatment

Obesity treatment plans should be tailored to patients on the basis of individual factors such as body mass index, existing medical conditions, and family history, Dr. Teixeira said.

Besides bariatric surgery, patients also may consider options such as counseling, lifestyle changes, and medications including the latest weight loss drugs, he added.

The clinical approach to obesity treatment has evolved, said Miguel Burch, MD, director of general surgery and chief of minimally invasive and gastrointestinal surgery at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, California, who was not involved in the survey.

“At one point in my career, I could say the only proven durable treatment for obesity is weight loss surgery. This was in the context of patients who were morbidly obese requiring risk reduction, not for a year or two but for decades, and not for 10-20 pounds but for 40-60 pounds of weight loss,” said Dr. Burch, who also directs the bariatric surgery program at Torrance Memorial Medical Center, Torrance, California.

“That was a previous era. We are now in a new one with the weight loss drugs,” Dr. Burch said. “In fact, it’s wonderful to have the opportunity to serve so many patients with an option other than just surgery.”

Still, Dr. Burch added, “we have to change the way we look at obesity management as being either surgery or medicine and start thinking about it more as a multidisciplinary approach to a chronic and potentially relapsing disease.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Working together

Dear Friends,

After 6 months in my first faculty position, I have come to appreciate the term “multidisciplinary approach” more than ever. Not only does this facilitate optimal patient care, but I have personally learned so much from experts in other fields. This theme resonates across this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, from treating complex gallbladder disease, to caring for sexual and gender minorities, and collaborating with the tech industry to advance patient care.

Our “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Andrew Gilman and Dr. Todd Baron, is on endoscopic management of gallbladder disease. They review endoscopic treatment options in patients with benign gallbladder disease, with emphasis on working with surgical and interventional radiology colleagues, as well as relaying endoscopic tips and techniques to achieve success in these complicated procedures.

In the “Short Clinical Reviews” section, Dr. David Chiang and Dr. Victor Chedid highlight the gaps in research and clinical care and competency for sexual and gender minorities, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. They describe the creation of the Pride in IBD clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., that creates a culturally sensitive space to care for this community.

As trainees transition to early faculty, becoming a mentor is a new role that can be very rewarding and daunting at the same time. Dr. Anna Lok, recipient of the AGA’s Distinguished Mentor Award, and Dr. Vincent Chen share invaluable experiences and advice on being a mentor from senior and early-career perspectives, respectively. Similarly in the transition to early faculty, Erin Anderson, CPA, answers five common financial questions that arise to better understand and manage a significant increase in salary.

Lastly, Dr. Shifa Umar describes her unique experience as part of the AGA’s annual Tech Summit Fellows Program, a cross-section of medicine, technology, and innovation.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu), or Jillian Schweitzer (jschweitzer@gastro.org), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The concept of the clinicopathologic conference (CPC) was introduced by Dr. Walter B. Cannon as a medical student at Harvard Medical School.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

After 6 months in my first faculty position, I have come to appreciate the term “multidisciplinary approach” more than ever. Not only does this facilitate optimal patient care, but I have personally learned so much from experts in other fields. This theme resonates across this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, from treating complex gallbladder disease, to caring for sexual and gender minorities, and collaborating with the tech industry to advance patient care.

Our “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Andrew Gilman and Dr. Todd Baron, is on endoscopic management of gallbladder disease. They review endoscopic treatment options in patients with benign gallbladder disease, with emphasis on working with surgical and interventional radiology colleagues, as well as relaying endoscopic tips and techniques to achieve success in these complicated procedures.

In the “Short Clinical Reviews” section, Dr. David Chiang and Dr. Victor Chedid highlight the gaps in research and clinical care and competency for sexual and gender minorities, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. They describe the creation of the Pride in IBD clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., that creates a culturally sensitive space to care for this community.

As trainees transition to early faculty, becoming a mentor is a new role that can be very rewarding and daunting at the same time. Dr. Anna Lok, recipient of the AGA’s Distinguished Mentor Award, and Dr. Vincent Chen share invaluable experiences and advice on being a mentor from senior and early-career perspectives, respectively. Similarly in the transition to early faculty, Erin Anderson, CPA, answers five common financial questions that arise to better understand and manage a significant increase in salary.

Lastly, Dr. Shifa Umar describes her unique experience as part of the AGA’s annual Tech Summit Fellows Program, a cross-section of medicine, technology, and innovation.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu), or Jillian Schweitzer (jschweitzer@gastro.org), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The concept of the clinicopathologic conference (CPC) was introduced by Dr. Walter B. Cannon as a medical student at Harvard Medical School.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

After 6 months in my first faculty position, I have come to appreciate the term “multidisciplinary approach” more than ever. Not only does this facilitate optimal patient care, but I have personally learned so much from experts in other fields. This theme resonates across this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, from treating complex gallbladder disease, to caring for sexual and gender minorities, and collaborating with the tech industry to advance patient care.

Our “In Focus” feature, written by Dr. Andrew Gilman and Dr. Todd Baron, is on endoscopic management of gallbladder disease. They review endoscopic treatment options in patients with benign gallbladder disease, with emphasis on working with surgical and interventional radiology colleagues, as well as relaying endoscopic tips and techniques to achieve success in these complicated procedures.

In the “Short Clinical Reviews” section, Dr. David Chiang and Dr. Victor Chedid highlight the gaps in research and clinical care and competency for sexual and gender minorities, particularly in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. They describe the creation of the Pride in IBD clinic at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., that creates a culturally sensitive space to care for this community.

As trainees transition to early faculty, becoming a mentor is a new role that can be very rewarding and daunting at the same time. Dr. Anna Lok, recipient of the AGA’s Distinguished Mentor Award, and Dr. Vincent Chen share invaluable experiences and advice on being a mentor from senior and early-career perspectives, respectively. Similarly in the transition to early faculty, Erin Anderson, CPA, answers five common financial questions that arise to better understand and manage a significant increase in salary.

Lastly, Dr. Shifa Umar describes her unique experience as part of the AGA’s annual Tech Summit Fellows Program, a cross-section of medicine, technology, and innovation.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu), or Jillian Schweitzer (jschweitzer@gastro.org), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The concept of the clinicopathologic conference (CPC) was introduced by Dr. Walter B. Cannon as a medical student at Harvard Medical School.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Moving the Field FORWARD

As an organization, AGA has invested heavily in programs and initiatives to support the professional development of its members across career stages. This includes programs such as the AGA-AASLD Academic Skills Workshop (in which I was fortunate to participate in 2016), Women’s Leadership and Executive Leadership Conferences (with the Midwest Women in GI Regional Workshop taking place later this month), and the AGA Research Foundation Awards Program, which distributes over $2 million in funding annually to support promising early career and senior investigators.

AGA’s Fostering Opportunities Resulting in Workforce and Research Diversity (FORWARD) Program, which was first funded by the National Institutes of Health in 2018 and is focused on improving the diversity of the GI research workforce, is another shining example. Led by Dr. Byron Cryer and Dr. Sandra Quezada, the program recently welcomed its 3rd cohort of participants, including 14 mentees and 28 senior and near-peer mentors.

We are pleased to frequently highlight these programs in the pages of GI & Hepatology News, and hope you enjoy learning more about each of these initiatives in future issues.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we highlight AGA’s newest Clinical Practice Guideline focused on management of pouchitis. We also report on the results of a recent RCT published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating the efficacy of thalidomide as a treatment for recurrent bleeding due to small-intestinal angiodysplasia and summarize other key journal content impacting your clinical practice. In our February Member Spotlight, we feature Dr. Rajeev Jain of Texas Digestive Disease Consultants, a former AGA Governing Board member, and learn about his advocacy work to improve patient care and reduce physician burnout through insurance coverage and MOC reform. We hope you enjoy this, and all the exciting content included in our February issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

As an organization, AGA has invested heavily in programs and initiatives to support the professional development of its members across career stages. This includes programs such as the AGA-AASLD Academic Skills Workshop (in which I was fortunate to participate in 2016), Women’s Leadership and Executive Leadership Conferences (with the Midwest Women in GI Regional Workshop taking place later this month), and the AGA Research Foundation Awards Program, which distributes over $2 million in funding annually to support promising early career and senior investigators.

AGA’s Fostering Opportunities Resulting in Workforce and Research Diversity (FORWARD) Program, which was first funded by the National Institutes of Health in 2018 and is focused on improving the diversity of the GI research workforce, is another shining example. Led by Dr. Byron Cryer and Dr. Sandra Quezada, the program recently welcomed its 3rd cohort of participants, including 14 mentees and 28 senior and near-peer mentors.

We are pleased to frequently highlight these programs in the pages of GI & Hepatology News, and hope you enjoy learning more about each of these initiatives in future issues.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we highlight AGA’s newest Clinical Practice Guideline focused on management of pouchitis. We also report on the results of a recent RCT published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating the efficacy of thalidomide as a treatment for recurrent bleeding due to small-intestinal angiodysplasia and summarize other key journal content impacting your clinical practice. In our February Member Spotlight, we feature Dr. Rajeev Jain of Texas Digestive Disease Consultants, a former AGA Governing Board member, and learn about his advocacy work to improve patient care and reduce physician burnout through insurance coverage and MOC reform. We hope you enjoy this, and all the exciting content included in our February issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

As an organization, AGA has invested heavily in programs and initiatives to support the professional development of its members across career stages. This includes programs such as the AGA-AASLD Academic Skills Workshop (in which I was fortunate to participate in 2016), Women’s Leadership and Executive Leadership Conferences (with the Midwest Women in GI Regional Workshop taking place later this month), and the AGA Research Foundation Awards Program, which distributes over $2 million in funding annually to support promising early career and senior investigators.

AGA’s Fostering Opportunities Resulting in Workforce and Research Diversity (FORWARD) Program, which was first funded by the National Institutes of Health in 2018 and is focused on improving the diversity of the GI research workforce, is another shining example. Led by Dr. Byron Cryer and Dr. Sandra Quezada, the program recently welcomed its 3rd cohort of participants, including 14 mentees and 28 senior and near-peer mentors.

We are pleased to frequently highlight these programs in the pages of GI & Hepatology News, and hope you enjoy learning more about each of these initiatives in future issues.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we highlight AGA’s newest Clinical Practice Guideline focused on management of pouchitis. We also report on the results of a recent RCT published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating the efficacy of thalidomide as a treatment for recurrent bleeding due to small-intestinal angiodysplasia and summarize other key journal content impacting your clinical practice. In our February Member Spotlight, we feature Dr. Rajeev Jain of Texas Digestive Disease Consultants, a former AGA Governing Board member, and learn about his advocacy work to improve patient care and reduce physician burnout through insurance coverage and MOC reform. We hope you enjoy this, and all the exciting content included in our February issue!

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Psychogenic Purpura

To the Editor:

A 14-year-old Black adolescent girl presented with episodic, painful, edematous plaques that occurred symmetrically on the arms and legs of 5 years’ duration. The plaques evolved into hyperpigmented patches within 24 to 48 hours before eventually resolving. Fatigue, headache, arthralgias of the arms and legs, chest pain, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting variably accompanied these episodes.

Prior to visiting our clinic, the patient had been seen by numerous specialists. A review of her medical records revealed an initial diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), then urticarial vasculitis. She had been treated with antihistamines, topical and systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, dapsone, azathioprine, and gabapentin. All treatments were ineffectual. She underwent extensive diagnostic testing and imaging, which were normal or noncontributory, including type I allergy testing; multiple exhaustive batteries of hematologic testing; and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvic region. Biopsies from symptomatic segments of the gastrointestinal tract were normal.

Chronic treatment with systemic steroids over 9 months resulted in gastritis and an episode of hematemesis requiring emergent hospitalization. A lengthy multidisciplinary evaluation was conducted at the patient’s local community hospital; the team concluded that she had an urticarial-type rash with accompanying symptoms that did not have an autoimmune, rheumatologic, or inflammatory basis.

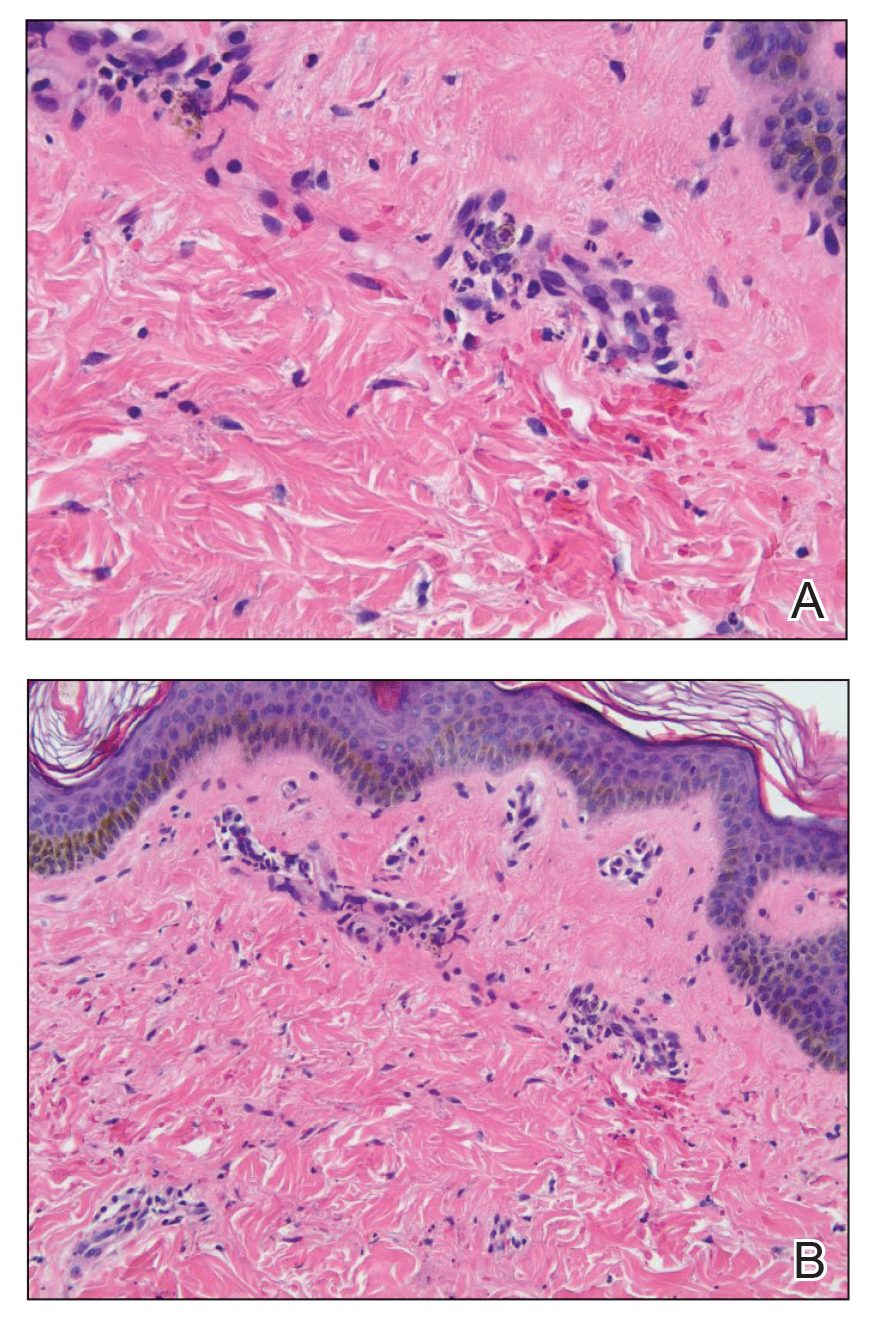

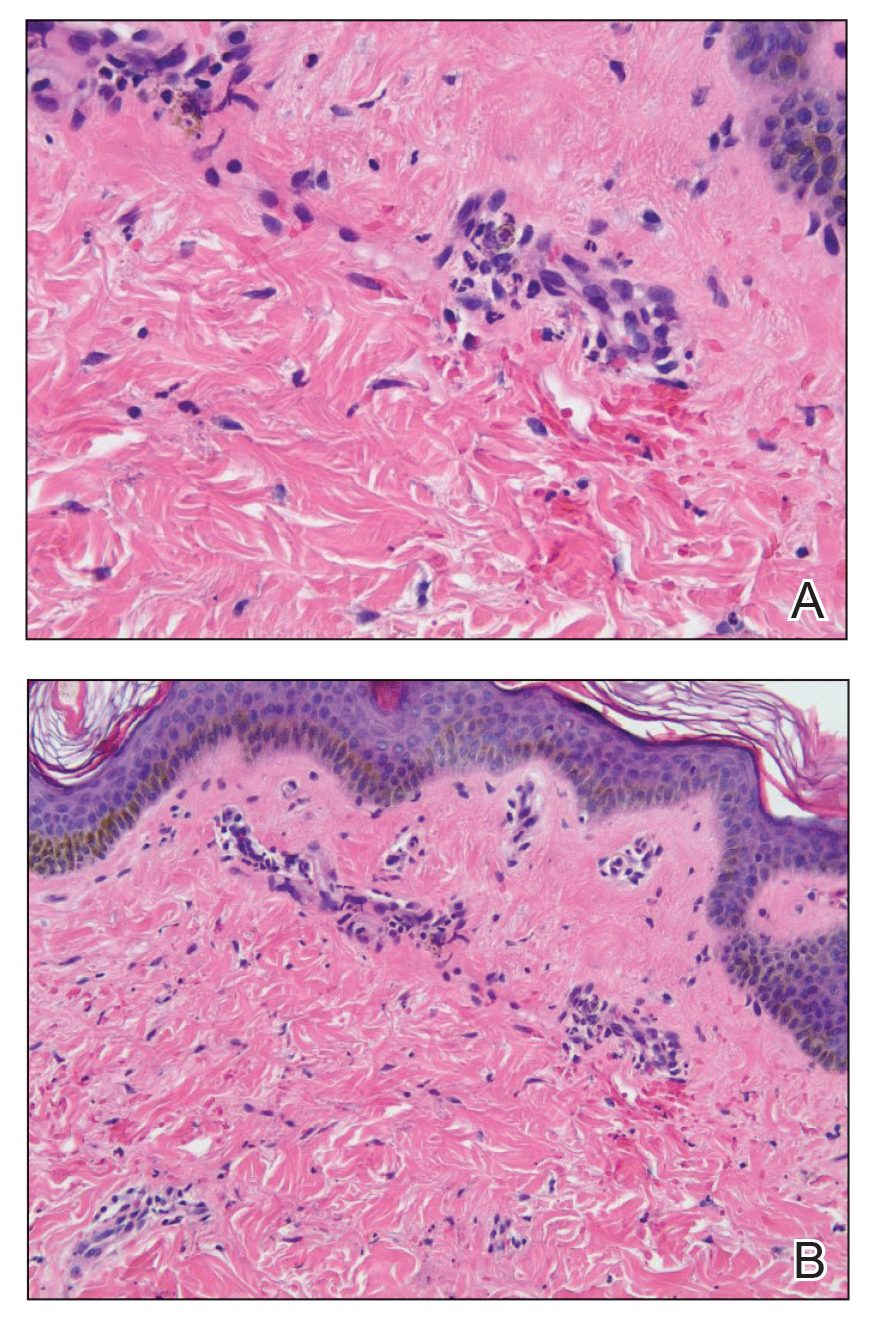

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for recent-onset panic attacks. Her family medical history was noncontributory. Physical examination revealed multiple violaceous hyperpigmented patches diffusely located on the proximal upper arms (Figure 1). There were no additional findings on physical examination.

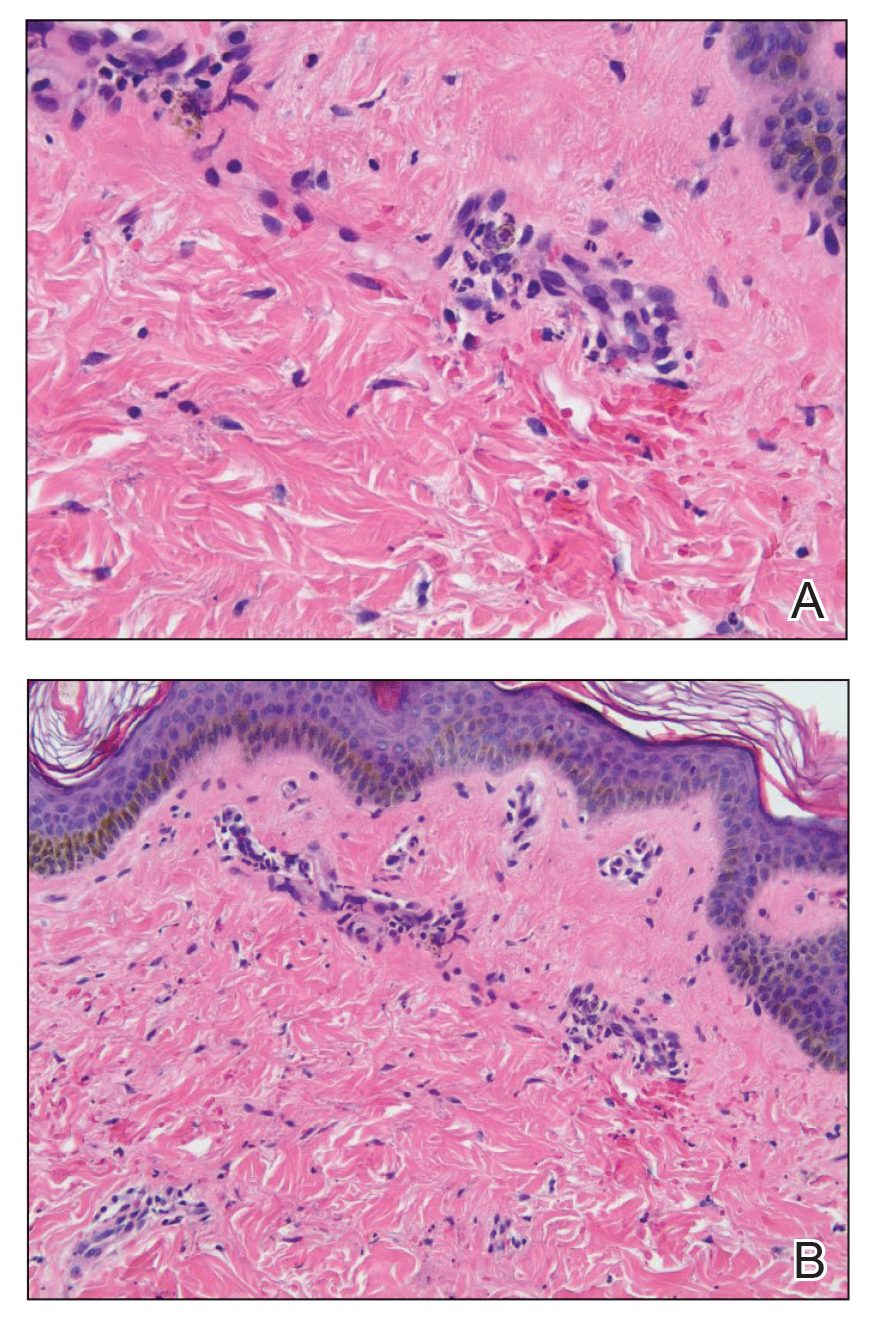

Punch biopsies were performed on lesional areas of the arm. Histopathology indicated a mild superficial perivascular dermal mixed infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing was negative for vasculitis. Immunohistochemical stains for CD117 and tryptase demonstrated a slight increase in the number of dermal mast cells; however, the increase was not sufficient to diagnose cutaneous mastocytosis, which was in the differential. We proposed a diagnosis of psychogenic purpura (PP)(also known as Gardner-Diamond syndrome). She was treated with gabapentin, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and cognitive therapy. Unfortunately, after starting therapy the patient was lost to follow-up.

Psychogenic purpura is a rare vasculopathy of unknown etiology that may be a special form of factitious disorder.1,2 In one study, PP occurred predominantly in females aged 15 to 66 years, with a median onset age of 33 years.3 A prodrome of localized itching, burning, and/or pain precedes the development of edematous plaques. The plaques evolve into painful ecchymoses within 1 to 2 days and resolve in 10 days or fewer without treatment. Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities but may occur anywhere on the body. The most common associated finding is an underlying depressive disorder. Episodes may be accompanied by headache, dizziness, fatigue, fever, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, menstrual irregularities, myalgia, and urologic conditions.

In 1955, Gardner and Diamond4 described the first cases of PP in 4 female patients at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. The investigators were able to replicate the painful ecchymoses with intradermal injection of the patient’s own erythrocytes into the skin. They proposed that the underlying pathogenesis involved autosensitization to erythrocyte stroma.4 Since then, others have suggested that the pathogenesis may include autosensitization to erythrocyte phosphatidylserine, tonus dysregulation of venous capillaries, abnormal endothelial fibrin synthesis, and capillary wall instability.5-7

Histopathology typically reveals superficial and deep perivascular inflammation with extravasated erythrocytes. Direct immunofluorescence is negative for vasculitis.8 Diagnostics and laboratory findings for underlying systemic illness are negative or noncontributory. Cutaneous injection of 1 mL of the patient’s own washed erythrocytes may result in the formation of the characteristic painful plaques within 24 hours; however, this test is limited by lack of standardization and low sensitivity.3

Psychogenic purpura may share clinical features with cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, such as HSP or urticarial vasculitis. Some of the findings that our patient was experiencing, including purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, are associated with HSP. However, HSP typically is self-limiting and classically features palpable purpura distributed across the lower extremities and buttocks. Histopathology demonstrates the classic findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; DIF typically is positive for perivascular IgA and C3 deposition. Increased serum IgA may be present.9 Urticarial vasculitis appears as erythematous indurated wheals that favor a proximal extremity and truncal distribution. They characteristically last longer than 24 hours, are frequently associated with nonprodromal pain or burning, and resolve with hyperpigmentation. Arthralgia and gastrointestinal, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic symptoms may be present, especially in patients with low complement levels.10 Skin biopsy demonstrates leukocytoclasia that must be accompanied by vessel wall necrosis. Fibrinoid deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, or perivascular inflammation may be present. In 70% of cases revealing perivascular immunoglobulin, C3, and fibrinogen deposition, DIF is positive. Serum C1q autoantibody may be associated with the hypocomplementemic form.10

The classic histopathologic findings in leukocytoclastic vasculitis include transmural neutrophilic infiltration of the walls of small vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, leukocytoclasia, extravasated erythrocytes, and signs of endothelial cell damage.9 A prior punch biopsy in this patient demonstrated rare neutrophilic nuclear debris within the vessel walls without fibrin deposition. Although the presence of nuclear debris and extravasated erythrocytes could be compatible with a manifestation of urticarial vasculitis, the lack of direct evidence of vessel wall necrosis combined with subsequent biopsies unequivocally ruled out cutaneous small vessel vasculitis in our patient.

Psychogenic purpura has been reported to occur frequently in the background of psycho-emotional distress. In 1989, Ratnoff11 noted that many of the patients he was treating at the University Hospitals of Cleveland, Ohio, had a depressive syndrome. A review of patients treated at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, illustrated concomitant psychiatric illnesses in 41 of 76 (54%) patients treated for PP, most commonly depressive, personality, and anxiety disorders.3

There is no consensus on therapy for PP. Treatment is based on providing symptomatic relief and relieving underlying psychiatric distress. Block et al12 found the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and psychotherapy to be successful in improving symptoms and reducing lesions at follow-up visits.

- Piette WW. Purpura: mechanisms and differential diagnosis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:376-389.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Factitious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372.

- Sridharan M, Ali U, Hook CC, et al. The Mayo Clinic experience with psychogenic purpura (Gardner-Diamond syndrome). Am J Med Sci. 2019;357:411‐420.

- Gardner FH, Diamond LK. Autoerythrocyte sensitization; a form of purpura producing painful bruising following autosensitization to red blood cells in certain women. Blood. 1955;10:675-690.

- Groch GS, Finch SC, Rogoway W, et al. Studies in the pathogenesis of autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome. Blood. 1966;28:19-33.

- Strunecká A, Krpejsová L, Palecek J, et al. Transbilayer redistribution of phosphatidylserine in erythrocytes of a patient with autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (psychogenic purpura). Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch. 1990;117:829-841.

- Merlen JF. Ecchymotic patches of the fingers and Gardner-Diamond vascular purpura. Phlebologie. 1987;40:473-487.

- Ivanov OL, Lvov AN, Michenko AV, et al. Autoerythrocyte sensitization syndrome (Gardner-Diamond syndrome): review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:499-504.

- Wetter DA, Dutz JP, Shinkai K, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:409-439.

- Hamad A, Jithpratuck W, Krishnaswamy G. Urticarial vasculitis and associated disorders. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:394-398.

- Ratnoff OD. Psychogenic purpura (autoerythrocyte sensitization): an unsolved dilemma. Am J Med. 1989;87:16N-21N.

- Block ME, Sitenga JL, Lehrer M, et al. Gardner‐Diamond syndrome: a systematic review of treatment options for a rare psychodermatological disorder. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:782-787.

To the Editor:

A 14-year-old Black adolescent girl presented with episodic, painful, edematous plaques that occurred symmetrically on the arms and legs of 5 years’ duration. The plaques evolved into hyperpigmented patches within 24 to 48 hours before eventually resolving. Fatigue, headache, arthralgias of the arms and legs, chest pain, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting variably accompanied these episodes.

Prior to visiting our clinic, the patient had been seen by numerous specialists. A review of her medical records revealed an initial diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), then urticarial vasculitis. She had been treated with antihistamines, topical and systemic steroids, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, dapsone, azathioprine, and gabapentin. All treatments were ineffectual. She underwent extensive diagnostic testing and imaging, which were normal or noncontributory, including type I allergy testing; multiple exhaustive batteries of hematologic testing; and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography of the brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvic region. Biopsies from symptomatic segments of the gastrointestinal tract were normal.

Chronic treatment with systemic steroids over 9 months resulted in gastritis and an episode of hematemesis requiring emergent hospitalization. A lengthy multidisciplinary evaluation was conducted at the patient’s local community hospital; the team concluded that she had an urticarial-type rash with accompanying symptoms that did not have an autoimmune, rheumatologic, or inflammatory basis.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for recent-onset panic attacks. Her family medical history was noncontributory. Physical examination revealed multiple violaceous hyperpigmented patches diffusely located on the proximal upper arms (Figure 1). There were no additional findings on physical examination.

Punch biopsies were performed on lesional areas of the arm. Histopathology indicated a mild superficial perivascular dermal mixed infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) testing was negative for vasculitis. Immunohistochemical stains for CD117 and tryptase demonstrated a slight increase in the number of dermal mast cells; however, the increase was not sufficient to diagnose cutaneous mastocytosis, which was in the differential. We proposed a diagnosis of psychogenic purpura (PP)(also known as Gardner-Diamond syndrome). She was treated with gabapentin, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and cognitive therapy. Unfortunately, after starting therapy the patient was lost to follow-up.

Psychogenic purpura is a rare vasculopathy of unknown etiology that may be a special form of factitious disorder.1,2 In one study, PP occurred predominantly in females aged 15 to 66 years, with a median onset age of 33 years.3 A prodrome of localized itching, burning, and/or pain precedes the development of edematous plaques. The plaques evolve into painful ecchymoses within 1 to 2 days and resolve in 10 days or fewer without treatment. Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities but may occur anywhere on the body. The most common associated finding is an underlying depressive disorder. Episodes may be accompanied by headache, dizziness, fatigue, fever, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, menstrual irregularities, myalgia, and urologic conditions.

In 1955, Gardner and Diamond4 described the first cases of PP in 4 female patients at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. The investigators were able to replicate the painful ecchymoses with intradermal injection of the patient’s own erythrocytes into the skin. They proposed that the underlying pathogenesis involved autosensitization to erythrocyte stroma.4 Since then, others have suggested that the pathogenesis may include autosensitization to erythrocyte phosphatidylserine, tonus dysregulation of venous capillaries, abnormal endothelial fibrin synthesis, and capillary wall instability.5-7

Histopathology typically reveals superficial and deep perivascular inflammation with extravasated erythrocytes. Direct immunofluorescence is negative for vasculitis.8 Diagnostics and laboratory findings for underlying systemic illness are negative or noncontributory. Cutaneous injection of 1 mL of the patient’s own washed erythrocytes may result in the formation of the characteristic painful plaques within 24 hours; however, this test is limited by lack of standardization and low sensitivity.3

Psychogenic purpura may share clinical features with cutaneous small vessel vasculitis, such as HSP or urticarial vasculitis. Some of the findings that our patient was experiencing, including purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, are associated with HSP. However, HSP typically is self-limiting and classically features palpable purpura distributed across the lower extremities and buttocks. Histopathology demonstrates the classic findings of leukocytoclastic vasculitis; DIF typically is positive for perivascular IgA and C3 deposition. Increased serum IgA may be present.9 Urticarial vasculitis appears as erythematous indurated wheals that favor a proximal extremity and truncal distribution. They characteristically last longer than 24 hours, are frequently associated with nonprodromal pain or burning, and resolve with hyperpigmentation. Arthralgia and gastrointestinal, renal, pulmonary, cardiac, and neurologic symptoms may be present, especially in patients with low complement levels.10 Skin biopsy demonstrates leukocytoclasia that must be accompanied by vessel wall necrosis. Fibrinoid deposition, erythrocyte extravasation, or perivascular inflammation may be present. In 70% of cases revealing perivascular immunoglobulin, C3, and fibrinogen deposition, DIF is positive. Serum C1q autoantibody may be associated with the hypocomplementemic form.10

The classic histopathologic findings in leukocytoclastic vasculitis include transmural neutrophilic infiltration of the walls of small vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls, leukocytoclasia, extravasated erythrocytes, and signs of endothelial cell damage.9 A prior punch biopsy in this patient demonstrated rare neutrophilic nuclear debris within the vessel walls without fibrin deposition. Although the presence of nuclear debris and extravasated erythrocytes could be compatible with a manifestation of urticarial vasculitis, the lack of direct evidence of vessel wall necrosis combined with subsequent biopsies unequivocally ruled out cutaneous small vessel vasculitis in our patient.

Psychogenic purpura has been reported to occur frequently in the background of psycho-emotional distress. In 1989, Ratnoff11 noted that many of the patients he was treating at the University Hospitals of Cleveland, Ohio, had a depressive syndrome. A review of patients treated at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, illustrated concomitant psychiatric illnesses in 41 of 76 (54%) patients treated for PP, most commonly depressive, personality, and anxiety disorders.3

There is no consensus on therapy for PP. Treatment is based on providing symptomatic relief and relieving underlying psychiatric distress. Block et al12 found the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and psychotherapy to be successful in improving symptoms and reducing lesions at follow-up visits.

To the Editor: