User login

Doctors With Limited Vacation Have Increased Burnout Risk

A recent study sheds light on the heightened risk for burnout among physicians who take infrequent vacations and engage in patient-related work during their time off.

Conducted by the American Medical Association (AMA), the study focuses on the United States, where labor regulations regarding vacation days and compensation differ from German norms. Despite this distinction, it provides valuable insights into the vacation behavior of doctors and its potential impact on burnout risk.

Christine A. Sinsky, MD, study author and senior physician advisor for physician satisfaction at the AMA, and her colleagues invited more than 90,000 physicians to participate in a survey that used postal and computer-based methods. In all, 3024 physicians, mainly those contacted by mail, filled out the questionnaire.

Limited Vacation Days

A significant proportion (59.6%) of respondents reported having taken fewer than 15 vacation days in the previous year, with nearly 20% taking fewer than 5 days off. Even when officially on vacation, most (70.4%) found themselves dealing with patient-related tasks. For one-third, these tasks consumed at least 30 minutes on a typical vacation day, often longer. This phenomenon was noted especially among female physicians.

Doctors who took less vacation and worked during their time off displayed higher emotional exhaustion and reported feeling less fulfilled in their profession.

Administrative Tasks

Administrative tasks, though no longer confined to paper, significantly influenced physicians’ vacation behavior. In the United States, handling messages from patients through the electronic health records (EHR) inbox demands a considerable amount of time.

Courses and tutorials on EHR inbox management are on the rise. A 2023 review linked electronic health records management to an increased burnout risk in the US medical community.

Lack of Coverage

Many physicians lack coverage for their EHR inbox during their absence. Less than half (49.1%) stated that someone else manages their inbox while they are on vacation.

Difficulty in finding coverage, whether for the EHR inbox or patient care, is a leading reason why many physicians seldom take more than 3 weeks of vacation per year. Financial considerations also contribute to this decision, as revealed in the survey.

Vacation Lowers Risk

Further analysis showed that doctors who took more than 3 weeks of vacation per year, which is not common, had a lower risk of developing burnout. Having coverage for vacation was also associated with reduced burnout risk and increased professional fulfillment.

However, these benefits applied only when physicians truly took a break during their vacation. Respondents who spent 30 minutes or more per day on patient-related work had a higher burnout risk. The risk was 1.58 times greater for 30-60 minutes, 1.97 times greater for 60-90 minutes, and 1.92 times greater for more than 90 minutes.

System-Level Interventions

The vacation behavior observed in this study likely exacerbates the effects of chronic workplace overload that are associated with long working hours, thus increasing the risk for burnout, according to the researchers.

“System-level measures must be implemented to ensure physicians take an appropriate number of vacation days,” wrote the researchers. “This includes having coverage available to handle clinical activities and administrative tasks, such as managing the EHR inbox. This could potentially reduce the burnout rate among physicians.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent study sheds light on the heightened risk for burnout among physicians who take infrequent vacations and engage in patient-related work during their time off.

Conducted by the American Medical Association (AMA), the study focuses on the United States, where labor regulations regarding vacation days and compensation differ from German norms. Despite this distinction, it provides valuable insights into the vacation behavior of doctors and its potential impact on burnout risk.

Christine A. Sinsky, MD, study author and senior physician advisor for physician satisfaction at the AMA, and her colleagues invited more than 90,000 physicians to participate in a survey that used postal and computer-based methods. In all, 3024 physicians, mainly those contacted by mail, filled out the questionnaire.

Limited Vacation Days

A significant proportion (59.6%) of respondents reported having taken fewer than 15 vacation days in the previous year, with nearly 20% taking fewer than 5 days off. Even when officially on vacation, most (70.4%) found themselves dealing with patient-related tasks. For one-third, these tasks consumed at least 30 minutes on a typical vacation day, often longer. This phenomenon was noted especially among female physicians.

Doctors who took less vacation and worked during their time off displayed higher emotional exhaustion and reported feeling less fulfilled in their profession.

Administrative Tasks

Administrative tasks, though no longer confined to paper, significantly influenced physicians’ vacation behavior. In the United States, handling messages from patients through the electronic health records (EHR) inbox demands a considerable amount of time.

Courses and tutorials on EHR inbox management are on the rise. A 2023 review linked electronic health records management to an increased burnout risk in the US medical community.

Lack of Coverage

Many physicians lack coverage for their EHR inbox during their absence. Less than half (49.1%) stated that someone else manages their inbox while they are on vacation.

Difficulty in finding coverage, whether for the EHR inbox or patient care, is a leading reason why many physicians seldom take more than 3 weeks of vacation per year. Financial considerations also contribute to this decision, as revealed in the survey.

Vacation Lowers Risk

Further analysis showed that doctors who took more than 3 weeks of vacation per year, which is not common, had a lower risk of developing burnout. Having coverage for vacation was also associated with reduced burnout risk and increased professional fulfillment.

However, these benefits applied only when physicians truly took a break during their vacation. Respondents who spent 30 minutes or more per day on patient-related work had a higher burnout risk. The risk was 1.58 times greater for 30-60 minutes, 1.97 times greater for 60-90 minutes, and 1.92 times greater for more than 90 minutes.

System-Level Interventions

The vacation behavior observed in this study likely exacerbates the effects of chronic workplace overload that are associated with long working hours, thus increasing the risk for burnout, according to the researchers.

“System-level measures must be implemented to ensure physicians take an appropriate number of vacation days,” wrote the researchers. “This includes having coverage available to handle clinical activities and administrative tasks, such as managing the EHR inbox. This could potentially reduce the burnout rate among physicians.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent study sheds light on the heightened risk for burnout among physicians who take infrequent vacations and engage in patient-related work during their time off.

Conducted by the American Medical Association (AMA), the study focuses on the United States, where labor regulations regarding vacation days and compensation differ from German norms. Despite this distinction, it provides valuable insights into the vacation behavior of doctors and its potential impact on burnout risk.

Christine A. Sinsky, MD, study author and senior physician advisor for physician satisfaction at the AMA, and her colleagues invited more than 90,000 physicians to participate in a survey that used postal and computer-based methods. In all, 3024 physicians, mainly those contacted by mail, filled out the questionnaire.

Limited Vacation Days

A significant proportion (59.6%) of respondents reported having taken fewer than 15 vacation days in the previous year, with nearly 20% taking fewer than 5 days off. Even when officially on vacation, most (70.4%) found themselves dealing with patient-related tasks. For one-third, these tasks consumed at least 30 minutes on a typical vacation day, often longer. This phenomenon was noted especially among female physicians.

Doctors who took less vacation and worked during their time off displayed higher emotional exhaustion and reported feeling less fulfilled in their profession.

Administrative Tasks

Administrative tasks, though no longer confined to paper, significantly influenced physicians’ vacation behavior. In the United States, handling messages from patients through the electronic health records (EHR) inbox demands a considerable amount of time.

Courses and tutorials on EHR inbox management are on the rise. A 2023 review linked electronic health records management to an increased burnout risk in the US medical community.

Lack of Coverage

Many physicians lack coverage for their EHR inbox during their absence. Less than half (49.1%) stated that someone else manages their inbox while they are on vacation.

Difficulty in finding coverage, whether for the EHR inbox or patient care, is a leading reason why many physicians seldom take more than 3 weeks of vacation per year. Financial considerations also contribute to this decision, as revealed in the survey.

Vacation Lowers Risk

Further analysis showed that doctors who took more than 3 weeks of vacation per year, which is not common, had a lower risk of developing burnout. Having coverage for vacation was also associated with reduced burnout risk and increased professional fulfillment.

However, these benefits applied only when physicians truly took a break during their vacation. Respondents who spent 30 minutes or more per day on patient-related work had a higher burnout risk. The risk was 1.58 times greater for 30-60 minutes, 1.97 times greater for 60-90 minutes, and 1.92 times greater for more than 90 minutes.

System-Level Interventions

The vacation behavior observed in this study likely exacerbates the effects of chronic workplace overload that are associated with long working hours, thus increasing the risk for burnout, according to the researchers.

“System-level measures must be implemented to ensure physicians take an appropriate number of vacation days,” wrote the researchers. “This includes having coverage available to handle clinical activities and administrative tasks, such as managing the EHR inbox. This could potentially reduce the burnout rate among physicians.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Mental Health Screening May Benefit Youth With Obesity

TOPLINE:

Mental health comorbidities are prevalent among youth with overweight or obesity, with the strongest risk factors being male sex, older age, and extreme obesity.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers compared clinical characteristics and outcomes among children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity with or without a comorbid mental disorder who participated in a lifestyle intervention program.

- Overall, data from 114,248 individuals (age, 6-30 years; 53% females) from 226 centers in Germany and Austria participating in the Adiposity Patient Registry were evaluated.

- Individuals were excluded if they had bariatric surgery or used weight-modifying drugs (metformin, orlistat, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues).

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as a standard deviation score (SDS) from a German youth population reference and was used to define overweight (90th to < 97th percentile), obesity (97th percentile), and severe obesity (≥ 99.5th percentile), which at age 18 correspond to adult cutoffs for overweight and obesity (25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively).

- Regression analysis identified the factors associated with mental disorders in those with overweight or obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- A comorbid mental disorder was reported in 3969 individuals, with attention-deficit disorder (ADHD, 42.5%), anxiety (31.3%), depression (24.3%), and eating disorders (12.9%) being the most common.

- The factors most strongly associated with mental health comorbidity were male sex (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52), older age (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62), and severe obesity (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.30-1.63).

- Mean BMI-SDS was higher in individuals with depression and eating disorders and lower in individuals with ADHD (both P < .001) than in those without mental disorders.

- Individuals with and without mental disorders benefited from similar BMI changes from lifestyle intervention programs.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Healthcare professionals caring for youth with overweight or obesity should be aware of comorbid mental disorders, and regular mental health screening should be considered.”

SOURCE:

This study, led by Angela Galler from the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, was published online on January 9, 2024, in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s findings are based on data from a group of children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity treated in specialized obesity centers and may not be generalizable to all youth with obesity. Moreover, the study could not establish any conclusions regarding the cause or effect between obesity and mental disorders. Individuals were not tested psychologically for mental disorders and might have been underreported.

DISCLOSURES:

The manuscript is part of the Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy project, which was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mental health comorbidities are prevalent among youth with overweight or obesity, with the strongest risk factors being male sex, older age, and extreme obesity.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers compared clinical characteristics and outcomes among children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity with or without a comorbid mental disorder who participated in a lifestyle intervention program.

- Overall, data from 114,248 individuals (age, 6-30 years; 53% females) from 226 centers in Germany and Austria participating in the Adiposity Patient Registry were evaluated.

- Individuals were excluded if they had bariatric surgery or used weight-modifying drugs (metformin, orlistat, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues).

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as a standard deviation score (SDS) from a German youth population reference and was used to define overweight (90th to < 97th percentile), obesity (97th percentile), and severe obesity (≥ 99.5th percentile), which at age 18 correspond to adult cutoffs for overweight and obesity (25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively).

- Regression analysis identified the factors associated with mental disorders in those with overweight or obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- A comorbid mental disorder was reported in 3969 individuals, with attention-deficit disorder (ADHD, 42.5%), anxiety (31.3%), depression (24.3%), and eating disorders (12.9%) being the most common.

- The factors most strongly associated with mental health comorbidity were male sex (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52), older age (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62), and severe obesity (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.30-1.63).

- Mean BMI-SDS was higher in individuals with depression and eating disorders and lower in individuals with ADHD (both P < .001) than in those without mental disorders.

- Individuals with and without mental disorders benefited from similar BMI changes from lifestyle intervention programs.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Healthcare professionals caring for youth with overweight or obesity should be aware of comorbid mental disorders, and regular mental health screening should be considered.”

SOURCE:

This study, led by Angela Galler from the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, was published online on January 9, 2024, in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s findings are based on data from a group of children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity treated in specialized obesity centers and may not be generalizable to all youth with obesity. Moreover, the study could not establish any conclusions regarding the cause or effect between obesity and mental disorders. Individuals were not tested psychologically for mental disorders and might have been underreported.

DISCLOSURES:

The manuscript is part of the Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy project, which was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mental health comorbidities are prevalent among youth with overweight or obesity, with the strongest risk factors being male sex, older age, and extreme obesity.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers compared clinical characteristics and outcomes among children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity with or without a comorbid mental disorder who participated in a lifestyle intervention program.

- Overall, data from 114,248 individuals (age, 6-30 years; 53% females) from 226 centers in Germany and Austria participating in the Adiposity Patient Registry were evaluated.

- Individuals were excluded if they had bariatric surgery or used weight-modifying drugs (metformin, orlistat, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues).

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as a standard deviation score (SDS) from a German youth population reference and was used to define overweight (90th to < 97th percentile), obesity (97th percentile), and severe obesity (≥ 99.5th percentile), which at age 18 correspond to adult cutoffs for overweight and obesity (25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively).

- Regression analysis identified the factors associated with mental disorders in those with overweight or obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- A comorbid mental disorder was reported in 3969 individuals, with attention-deficit disorder (ADHD, 42.5%), anxiety (31.3%), depression (24.3%), and eating disorders (12.9%) being the most common.

- The factors most strongly associated with mental health comorbidity were male sex (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52), older age (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62), and severe obesity (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.30-1.63).

- Mean BMI-SDS was higher in individuals with depression and eating disorders and lower in individuals with ADHD (both P < .001) than in those without mental disorders.

- Individuals with and without mental disorders benefited from similar BMI changes from lifestyle intervention programs.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Healthcare professionals caring for youth with overweight or obesity should be aware of comorbid mental disorders, and regular mental health screening should be considered.”

SOURCE:

This study, led by Angela Galler from the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, was published online on January 9, 2024, in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s findings are based on data from a group of children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity treated in specialized obesity centers and may not be generalizable to all youth with obesity. Moreover, the study could not establish any conclusions regarding the cause or effect between obesity and mental disorders. Individuals were not tested psychologically for mental disorders and might have been underreported.

DISCLOSURES:

The manuscript is part of the Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy project, which was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Study Concludes Most Melanoma Overdiagnoses Are In Situ

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The increase in melanoma diagnoses in the United States, while mortality has remained flat, has raised concerns about overdiagnosis of melanoma, cases that may not result in harm if left untreated. How much of the overdiagnoses can be attributed to melanoma in situ vs invasive melanoma is unknown.

- To address this question, researchers collected data from the SEER 9 registries database.

- They used DevCan software to calculate the cumulative lifetime risk of White American men and women being diagnosed with melanoma between 1975 and 2018, adjusting for changes in longevity and risk factors over the study period.

- The primary outcome was excess lifetime risk for melanoma diagnosis between 1976 and 2018, adjusted for year 2018 competing mortality and changes in risk factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers found that between 1975 and 2018, the adjusted lifetime risk of being diagnosed with melanoma in situ increased from 0.17% to 2.7% in White men and 0.08% to 2% in White women.

- An estimated 49.7% and 64.6% of melanomas diagnosed in White men and White women, respectively, were overdiagnosed in 2018.

- Among individuals diagnosed with melanoma in situ, 89.4% of White men and 85.4% of White women were likely overdiagnosed in 2018.

IN PRACTICE:

“A large proportion of overdiagnosed melanomas are in situ cancers, pointing to a potential area to focus for an intervention de-escalation of the intensity of treatment and survivorship care,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Adewole S. Adamson, MD, of the Division of Dermatology at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School, led the research. The study was published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine on January 19, 2024.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis only involved White individuals. Other limitations include a high risk for selection bias and that the researchers assumed no melanoma diagnosis in 1975, which may not be the case.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Adamson disclosed that he is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through The Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program. Coauthor Katy J.L. Bell, MBchB, PhD, of the University of Sydney, is supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The increase in melanoma diagnoses in the United States, while mortality has remained flat, has raised concerns about overdiagnosis of melanoma, cases that may not result in harm if left untreated. How much of the overdiagnoses can be attributed to melanoma in situ vs invasive melanoma is unknown.

- To address this question, researchers collected data from the SEER 9 registries database.

- They used DevCan software to calculate the cumulative lifetime risk of White American men and women being diagnosed with melanoma between 1975 and 2018, adjusting for changes in longevity and risk factors over the study period.

- The primary outcome was excess lifetime risk for melanoma diagnosis between 1976 and 2018, adjusted for year 2018 competing mortality and changes in risk factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers found that between 1975 and 2018, the adjusted lifetime risk of being diagnosed with melanoma in situ increased from 0.17% to 2.7% in White men and 0.08% to 2% in White women.

- An estimated 49.7% and 64.6% of melanomas diagnosed in White men and White women, respectively, were overdiagnosed in 2018.

- Among individuals diagnosed with melanoma in situ, 89.4% of White men and 85.4% of White women were likely overdiagnosed in 2018.

IN PRACTICE:

“A large proportion of overdiagnosed melanomas are in situ cancers, pointing to a potential area to focus for an intervention de-escalation of the intensity of treatment and survivorship care,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Adewole S. Adamson, MD, of the Division of Dermatology at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School, led the research. The study was published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine on January 19, 2024.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis only involved White individuals. Other limitations include a high risk for selection bias and that the researchers assumed no melanoma diagnosis in 1975, which may not be the case.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Adamson disclosed that he is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through The Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program. Coauthor Katy J.L. Bell, MBchB, PhD, of the University of Sydney, is supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- The increase in melanoma diagnoses in the United States, while mortality has remained flat, has raised concerns about overdiagnosis of melanoma, cases that may not result in harm if left untreated. How much of the overdiagnoses can be attributed to melanoma in situ vs invasive melanoma is unknown.

- To address this question, researchers collected data from the SEER 9 registries database.

- They used DevCan software to calculate the cumulative lifetime risk of White American men and women being diagnosed with melanoma between 1975 and 2018, adjusting for changes in longevity and risk factors over the study period.

- The primary outcome was excess lifetime risk for melanoma diagnosis between 1976 and 2018, adjusted for year 2018 competing mortality and changes in risk factors.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers found that between 1975 and 2018, the adjusted lifetime risk of being diagnosed with melanoma in situ increased from 0.17% to 2.7% in White men and 0.08% to 2% in White women.

- An estimated 49.7% and 64.6% of melanomas diagnosed in White men and White women, respectively, were overdiagnosed in 2018.

- Among individuals diagnosed with melanoma in situ, 89.4% of White men and 85.4% of White women were likely overdiagnosed in 2018.

IN PRACTICE:

“A large proportion of overdiagnosed melanomas are in situ cancers, pointing to a potential area to focus for an intervention de-escalation of the intensity of treatment and survivorship care,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Adewole S. Adamson, MD, of the Division of Dermatology at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School, led the research. The study was published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine on January 19, 2024.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis only involved White individuals. Other limitations include a high risk for selection bias and that the researchers assumed no melanoma diagnosis in 1975, which may not be the case.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Adamson disclosed that he is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation through The Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program. Coauthor Katy J.L. Bell, MBchB, PhD, of the University of Sydney, is supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rituximab Results in Sustained Remission for Pemphigus, Study Found

TOPLINE:

, an analysis showed.

METHODOLOGY:

- The short-term efficacy and safety of first-line treatment with rituximab for pemphigus were demonstrated in the Ritux 3 trial, but the rates of long-term remission are unknown.

- French investigators from 25 dermatology departments evaluated 83 patients from the Ritux 3 trial between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2015.

- They used Kaplan-Meir curves to determine the 5- and 7-year rates of disease-free survival (DFS) without corticosteroids.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 83 patients, 44 were in the rituximab-plus-prednisone group and 39 were in the prednisone-only group, with a median follow-up of 87.3 months (7.3 years).

- Among patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group, 43 (93.5%) achieved complete remission without corticosteroids at any time during follow-up, compared with 17 patients (39%) in the prednisone-only group.

- DFS (without corticosteroid therapy) statistically favored patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group compared with patients in the prednisone-only group at follow-up times of 5 years (76.7% vs 35.3%, respectively) and 7 years (72.1% vs 35.3%; P < .001 for both associations).

- In another finding, 31 patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group reported fewer serious adverse events (SAEs) than 58 patients in the prednisone-only group, which corresponds to 0.67 and 1.32 SAEs per patient, respectively (P = .003).

IN PRACTICE:

The study findings demonstrated “the superiority of rituximab over a standard corticosteroids regimen, both in the short term and the long term,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Corresponding author Billal Tedbirt, MD, of the Department of Dermatology at CHU Rouen in France, led the study, which was published online on January 24, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Nearly 8% of patients did not attend the end of follow-up visit. Also, serum samples used to predict relapse were drawn at month 36, but the researchers said that a window of every 4-6 months might provide higher accuracy of relapses.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Tedbirt reported having no disclosures. Four of the study authors reported being investigators for and/or receiving personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies. The study was supported by a grant from the French Society of Dermatology.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, an analysis showed.

METHODOLOGY:

- The short-term efficacy and safety of first-line treatment with rituximab for pemphigus were demonstrated in the Ritux 3 trial, but the rates of long-term remission are unknown.

- French investigators from 25 dermatology departments evaluated 83 patients from the Ritux 3 trial between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2015.

- They used Kaplan-Meir curves to determine the 5- and 7-year rates of disease-free survival (DFS) without corticosteroids.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 83 patients, 44 were in the rituximab-plus-prednisone group and 39 were in the prednisone-only group, with a median follow-up of 87.3 months (7.3 years).

- Among patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group, 43 (93.5%) achieved complete remission without corticosteroids at any time during follow-up, compared with 17 patients (39%) in the prednisone-only group.

- DFS (without corticosteroid therapy) statistically favored patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group compared with patients in the prednisone-only group at follow-up times of 5 years (76.7% vs 35.3%, respectively) and 7 years (72.1% vs 35.3%; P < .001 for both associations).

- In another finding, 31 patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group reported fewer serious adverse events (SAEs) than 58 patients in the prednisone-only group, which corresponds to 0.67 and 1.32 SAEs per patient, respectively (P = .003).

IN PRACTICE:

The study findings demonstrated “the superiority of rituximab over a standard corticosteroids regimen, both in the short term and the long term,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Corresponding author Billal Tedbirt, MD, of the Department of Dermatology at CHU Rouen in France, led the study, which was published online on January 24, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Nearly 8% of patients did not attend the end of follow-up visit. Also, serum samples used to predict relapse were drawn at month 36, but the researchers said that a window of every 4-6 months might provide higher accuracy of relapses.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Tedbirt reported having no disclosures. Four of the study authors reported being investigators for and/or receiving personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies. The study was supported by a grant from the French Society of Dermatology.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, an analysis showed.

METHODOLOGY:

- The short-term efficacy and safety of first-line treatment with rituximab for pemphigus were demonstrated in the Ritux 3 trial, but the rates of long-term remission are unknown.

- French investigators from 25 dermatology departments evaluated 83 patients from the Ritux 3 trial between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2015.

- They used Kaplan-Meir curves to determine the 5- and 7-year rates of disease-free survival (DFS) without corticosteroids.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 83 patients, 44 were in the rituximab-plus-prednisone group and 39 were in the prednisone-only group, with a median follow-up of 87.3 months (7.3 years).

- Among patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group, 43 (93.5%) achieved complete remission without corticosteroids at any time during follow-up, compared with 17 patients (39%) in the prednisone-only group.

- DFS (without corticosteroid therapy) statistically favored patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group compared with patients in the prednisone-only group at follow-up times of 5 years (76.7% vs 35.3%, respectively) and 7 years (72.1% vs 35.3%; P < .001 for both associations).

- In another finding, 31 patients in the rituximab plus prednisone group reported fewer serious adverse events (SAEs) than 58 patients in the prednisone-only group, which corresponds to 0.67 and 1.32 SAEs per patient, respectively (P = .003).

IN PRACTICE:

The study findings demonstrated “the superiority of rituximab over a standard corticosteroids regimen, both in the short term and the long term,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Corresponding author Billal Tedbirt, MD, of the Department of Dermatology at CHU Rouen in France, led the study, which was published online on January 24, 2024, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Nearly 8% of patients did not attend the end of follow-up visit. Also, serum samples used to predict relapse were drawn at month 36, but the researchers said that a window of every 4-6 months might provide higher accuracy of relapses.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Tedbirt reported having no disclosures. Four of the study authors reported being investigators for and/or receiving personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies. The study was supported by a grant from the French Society of Dermatology.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Microbiome Impacts Vaccine Responses

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

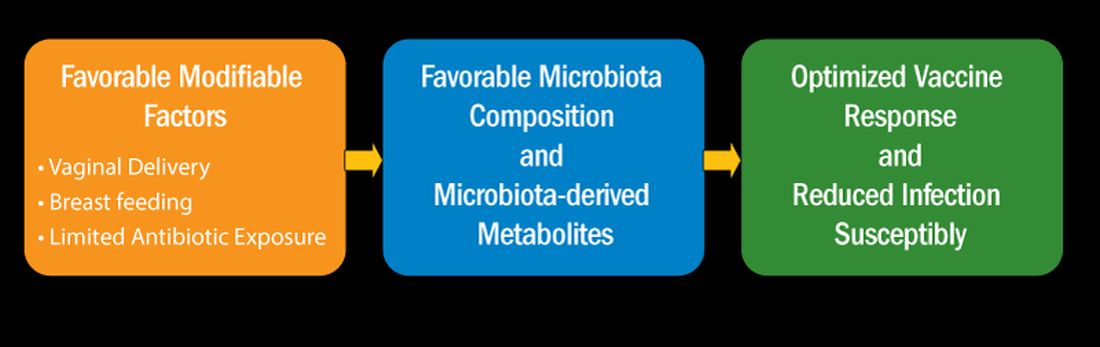

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

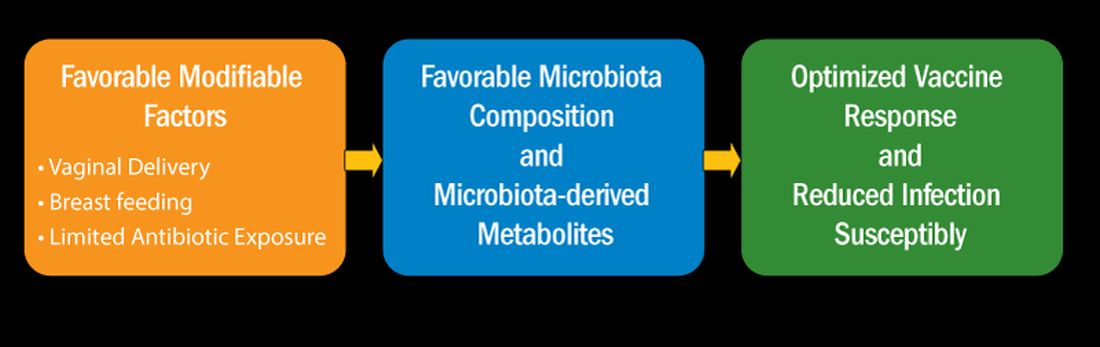

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

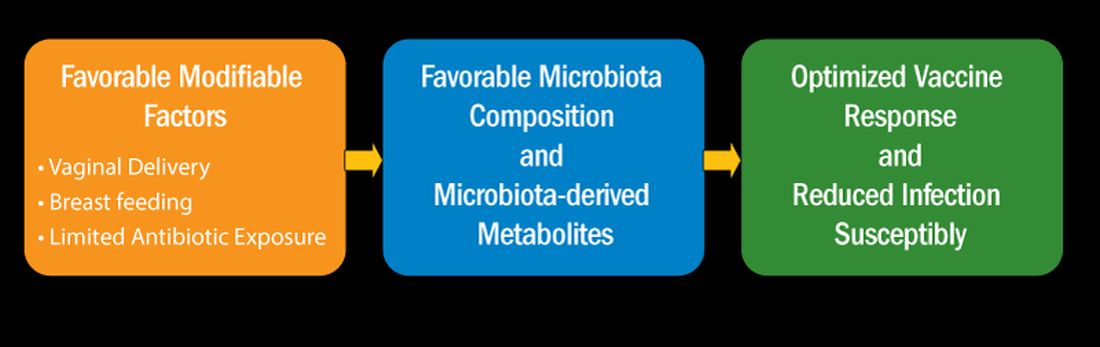

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

Ibuprofen Fails for Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Stockholm3 Prostate Test Bests PSA for Prostate Cancer Risk in North America

The Stockholm3 (A3P Biomedical) multiparametic blood test has shown accuracy in assessing the risk of prostate cancer, exceeding that of the standard prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based test, in Swedish patients.

“The Stockholm3 outperformed the PSA test overall and in every subcohort, with an impressive reduction of unnecessary biopsies of 40% to 50%, while maintaining relative sensitivity,” first author Scott E. Eggener, MD, said in presenting the findings at the ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. The test “has attractive characteristics in a diverse cohort, including within various racial and ethnic subgroups,” added Dr. Eggener, professor of surgery and radiology at the University of Chicago.

While the PSA test, the standard-of-care in prostate cancer risk assessment, reduces mortality, the test is known to have a risk for false positive results, leading to unnecessary prostate biopsies, as well as overdiagnosis of low-risk prostate cancers, Dr. Eggener explained in his talk.

Randomized trials do show “fewer men die from prostate cancer with screening [with PSA testing], however, the likelihood of unnecessarily finding out about a cancer, undergoing treatment, and exposure to potential treatment-related side effects is significantly higher,” Dr. Eggener said in a interview.

The Stockholm3 clinical diagnostic prostate cancer test, which has been used in Sweden and Norway since 2017, was validated in a sample of nearly 60,000 men in the STHLM3 study (doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[15]00361-7), which was published in The Lancet Oncology in December 2015. That study showed significant improvement over PSA alone detection of prostate cancers with a Gleason score of at least 7 (P < .0001), Dr. Eggener explained.

The test combines five plasma protein markers, including total and free PSA, PSP94, GDF-15 and KLK2, along with 101 genetic markers and clinical patient data, including age, previous biopsy results and family history.

Because the Stockholm3 test was validated in a Swedish population cohort, evidence on the accuracy of the test in other racial and ethnic populations is lacking, the authors noted in the abstract.

Study Methods and Results

To further investigate, Dr. Eggener and his colleagues conducted the prospective SEPTA trial, involving 2,129 men with no known prostate cancer but clinical indications for prostate biopsy, who were referred for prostate biopsy at 17 North American sites between 2019 and 2023.

Among the men, 24% were self-identified as African American/Black; 46% were White/Caucasian; 14% were Hispanic/Latina; and 16% were Asian. The men’s median age was 63; their median PSA value was 6.1 ng/mL, according to the abstract.

Of the patients, 16% received magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-targeted biopsies and 20% had prior benign biopsies, the abstract notes.

Biopsy results showed that clinically significant prostate cancer, defined as International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Gleason Grade group ≥ 2, was detected in 29% of patients, with 14% having ISUP 1 cancer and 57% of cases having been benign, according to the abstract.

Overall detection rates of grade 2 or higher were 37% for African American/Black, 28% for White/Caucasian, 29% for Hispanic/Latino, and 21% Asian.

In terms of sensitivity of the two tests, the Stockholm3 (cut-point of ≥ 15) was noninferior compared with the traditional PSA cut-point of ≥ 4 ng/mL (relative sensitivity 0.95).

Results were consistent across ethnic subgroups: noninferior sensitivity (0.91-0.98) and superior specificity (2.51-4.70), the abstract authors reported.

Compared with the use of the PSA test’s cut-point of ≥ 4 ng/mL, the use of Stockholm3’s cut-point of ≥ 15 or higher would have reduced unnecessary biopsies by 45% overall, including by 46% among Asian and Black/African American patients, by 53% in Hispanic patients and 42% in White patients, according to the abstract.

Overall, “utilization of Stockholm3 improves the net benefit:harm ratio of PSA screening by identifying nearly all men with Gleason Grade 2 or higher, while minimizing the number of men undergoing biopsy who show no cancer or an indolent cancer (Gleason Grade 1),” Dr. Eggener said in an interview.

Stockholm3 Expected to be Available in U.S. This Year

The test, which has been available in Sweden since 2018, is expected to become commercially available in the United States in early 2024. Dr. Eggener noted that “cost of the test hasn’t been finalized, but will be considerably more expensive than PSA, which is very cheap.”

Commenting on the findings, Bradley McGregor, MD, of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and an ASCO oncology expert, noted that “ultimately, the goal [of prostate screening] is to be able to better decide when a biopsy is going to yield a clinically relevant prostate cancer, [and] this study gives us some insight of the use of the Stockholm3 tool in a more diverse population.

“How the tool will be utilized in the clinic and in guidelines is something that is a work in progress,” he added. “But I think this provides some reassurances that this will have implications beyond just the homogeneous populations in the original studies.”

Dr. McGregor noted that considerations of the issue of cost should be weighed against the potential costs involved in unnecessary biopsies and a host of other costs that can arise with an inaccurate risk assessment.

“If there is a way to avoid those costs and help us have more confidence in the prostate test results and intervene at an earlier stage, I think that’s exciting,” he said.

Dr. Eggener has consulted for A3P Biomedical but had no financial relationship with the company to disclose.

The Stockholm3 (A3P Biomedical) multiparametic blood test has shown accuracy in assessing the risk of prostate cancer, exceeding that of the standard prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based test, in Swedish patients.

“The Stockholm3 outperformed the PSA test overall and in every subcohort, with an impressive reduction of unnecessary biopsies of 40% to 50%, while maintaining relative sensitivity,” first author Scott E. Eggener, MD, said in presenting the findings at the ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. The test “has attractive characteristics in a diverse cohort, including within various racial and ethnic subgroups,” added Dr. Eggener, professor of surgery and radiology at the University of Chicago.

While the PSA test, the standard-of-care in prostate cancer risk assessment, reduces mortality, the test is known to have a risk for false positive results, leading to unnecessary prostate biopsies, as well as overdiagnosis of low-risk prostate cancers, Dr. Eggener explained in his talk.

Randomized trials do show “fewer men die from prostate cancer with screening [with PSA testing], however, the likelihood of unnecessarily finding out about a cancer, undergoing treatment, and exposure to potential treatment-related side effects is significantly higher,” Dr. Eggener said in a interview.

The Stockholm3 clinical diagnostic prostate cancer test, which has been used in Sweden and Norway since 2017, was validated in a sample of nearly 60,000 men in the STHLM3 study (doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[15]00361-7), which was published in The Lancet Oncology in December 2015. That study showed significant improvement over PSA alone detection of prostate cancers with a Gleason score of at least 7 (P < .0001), Dr. Eggener explained.

The test combines five plasma protein markers, including total and free PSA, PSP94, GDF-15 and KLK2, along with 101 genetic markers and clinical patient data, including age, previous biopsy results and family history.

Because the Stockholm3 test was validated in a Swedish population cohort, evidence on the accuracy of the test in other racial and ethnic populations is lacking, the authors noted in the abstract.

Study Methods and Results

To further investigate, Dr. Eggener and his colleagues conducted the prospective SEPTA trial, involving 2,129 men with no known prostate cancer but clinical indications for prostate biopsy, who were referred for prostate biopsy at 17 North American sites between 2019 and 2023.

Among the men, 24% were self-identified as African American/Black; 46% were White/Caucasian; 14% were Hispanic/Latina; and 16% were Asian. The men’s median age was 63; their median PSA value was 6.1 ng/mL, according to the abstract.

Of the patients, 16% received magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-targeted biopsies and 20% had prior benign biopsies, the abstract notes.

Biopsy results showed that clinically significant prostate cancer, defined as International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Gleason Grade group ≥ 2, was detected in 29% of patients, with 14% having ISUP 1 cancer and 57% of cases having been benign, according to the abstract.

Overall detection rates of grade 2 or higher were 37% for African American/Black, 28% for White/Caucasian, 29% for Hispanic/Latino, and 21% Asian.

In terms of sensitivity of the two tests, the Stockholm3 (cut-point of ≥ 15) was noninferior compared with the traditional PSA cut-point of ≥ 4 ng/mL (relative sensitivity 0.95).

Results were consistent across ethnic subgroups: noninferior sensitivity (0.91-0.98) and superior specificity (2.51-4.70), the abstract authors reported.

Compared with the use of the PSA test’s cut-point of ≥ 4 ng/mL, the use of Stockholm3’s cut-point of ≥ 15 or higher would have reduced unnecessary biopsies by 45% overall, including by 46% among Asian and Black/African American patients, by 53% in Hispanic patients and 42% in White patients, according to the abstract.

Overall, “utilization of Stockholm3 improves the net benefit:harm ratio of PSA screening by identifying nearly all men with Gleason Grade 2 or higher, while minimizing the number of men undergoing biopsy who show no cancer or an indolent cancer (Gleason Grade 1),” Dr. Eggener said in an interview.

Stockholm3 Expected to be Available in U.S. This Year

The test, which has been available in Sweden since 2018, is expected to become commercially available in the United States in early 2024. Dr. Eggener noted that “cost of the test hasn’t been finalized, but will be considerably more expensive than PSA, which is very cheap.”

Commenting on the findings, Bradley McGregor, MD, of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and an ASCO oncology expert, noted that “ultimately, the goal [of prostate screening] is to be able to better decide when a biopsy is going to yield a clinically relevant prostate cancer, [and] this study gives us some insight of the use of the Stockholm3 tool in a more diverse population.

“How the tool will be utilized in the clinic and in guidelines is something that is a work in progress,” he added. “But I think this provides some reassurances that this will have implications beyond just the homogeneous populations in the original studies.”

Dr. McGregor noted that considerations of the issue of cost should be weighed against the potential costs involved in unnecessary biopsies and a host of other costs that can arise with an inaccurate risk assessment.

“If there is a way to avoid those costs and help us have more confidence in the prostate test results and intervene at an earlier stage, I think that’s exciting,” he said.

Dr. Eggener has consulted for A3P Biomedical but had no financial relationship with the company to disclose.

The Stockholm3 (A3P Biomedical) multiparametic blood test has shown accuracy in assessing the risk of prostate cancer, exceeding that of the standard prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based test, in Swedish patients.

“The Stockholm3 outperformed the PSA test overall and in every subcohort, with an impressive reduction of unnecessary biopsies of 40% to 50%, while maintaining relative sensitivity,” first author Scott E. Eggener, MD, said in presenting the findings at the ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. The test “has attractive characteristics in a diverse cohort, including within various racial and ethnic subgroups,” added Dr. Eggener, professor of surgery and radiology at the University of Chicago.

While the PSA test, the standard-of-care in prostate cancer risk assessment, reduces mortality, the test is known to have a risk for false positive results, leading to unnecessary prostate biopsies, as well as overdiagnosis of low-risk prostate cancers, Dr. Eggener explained in his talk.

Randomized trials do show “fewer men die from prostate cancer with screening [with PSA testing], however, the likelihood of unnecessarily finding out about a cancer, undergoing treatment, and exposure to potential treatment-related side effects is significantly higher,” Dr. Eggener said in a interview.

The Stockholm3 clinical diagnostic prostate cancer test, which has been used in Sweden and Norway since 2017, was validated in a sample of nearly 60,000 men in the STHLM3 study (doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[15]00361-7), which was published in The Lancet Oncology in December 2015. That study showed significant improvement over PSA alone detection of prostate cancers with a Gleason score of at least 7 (P < .0001), Dr. Eggener explained.

The test combines five plasma protein markers, including total and free PSA, PSP94, GDF-15 and KLK2, along with 101 genetic markers and clinical patient data, including age, previous biopsy results and family history.

Because the Stockholm3 test was validated in a Swedish population cohort, evidence on the accuracy of the test in other racial and ethnic populations is lacking, the authors noted in the abstract.

Study Methods and Results

To further investigate, Dr. Eggener and his colleagues conducted the prospective SEPTA trial, involving 2,129 men with no known prostate cancer but clinical indications for prostate biopsy, who were referred for prostate biopsy at 17 North American sites between 2019 and 2023.