User login

Aspirin plus a DOAC may do more harm than good in some

ORLANDO – in a large registry-based cohort.

The study, which involved a cohort of 2,045 patients who were followed at 6 anticoagulation clinics in Michigan during January 2009–June 2019, also found no apparent improvement in thrombosis incidence with the addition of aspirin, Jordan K. Schaefer, MD, reported during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Of the cohort patients, 639 adults who received a DOAC plus aspirin after VTE or for NVAF without a clear indication were compared with 639 propensity-matched controls. The bleeding event rate per 100 patient years was 39.50 vs. 32.32 at an average of 15.2 months of follow-up in the combination therapy and DOAC monotherapy groups, respectively, said Dr. Schaefer of the division of hematology/oncology, department of internal medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“This result was statistically significant for clinically relevant non-major bleeding, with an 18.7 rate per 100 patient years, compared with 13.5 for DOAC monotherapy,” (P = .02), he said. “We also saw a significant increase in non-major bleeding with combination therapy, compared with direct oral anticoagulant monotherapy” (rate, 32.82 vs. 25.88; P =.04).

No significant difference was seen overall (P =.07) or for other specific types of bleeding, he noted.

The observed rates of thrombosis in the groups, respectively, were 2.35 and 2.23 per 100 patient years (P =.95), he said, noting that patients on combination therapy also had more emergency department visits and hospitalizations, but those differences were not statistically significant.

“Direct-acting oral anticoagulants, which include apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban, are increasingly used in clinical practice for indications that include the prevention of strokes for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, and the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolic disease,” Dr. Schaefer said.

Aspirin is commonly used in clinical practice for various indications, including primary prevention of heart attacks, strokes, and colorectal cancer, as well as for thromboprophylaxis in patients with certain blood disorders or with certain cardiac devices, he added.

“Aspirin is used for the secondary prevention of thrombosis for patients with known coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, or carotid artery disease,” he said. “And while adding aspirin to a DOAC is often appropriate after acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous coronary intervention, many patients receive the combination therapy without a clear indication, he said, noting that increasing evidence in recent years, largely from patients treated with warfarin and aspirin, suggest that the approach may do more harm than good for certain patients.

Specifically, there’s a question of whether aspirin is increasing the rates of bleeding without protecting patients from adverse thrombotic outcomes.

“This has specifically been a concern for patients who are on full-dose anticoagulation,” he said.

In the current study, patient demographics, comorbidities, and concurrent medications were well balanced in the treatment and control groups after propensity score matching, he said, noting that patients with a history of heart valve replacement, recent MI, or less than 3 months of follow-up were excluded.

“These findings need to be confirmed in larger studies, but until such data [are] available, clinicians and patients should continue to balance the relative risks and benefits of adding aspirin to their direct oral anticoagulant therapy,” Dr. Schaefer said. “Further research needs to evaluate key subgroups to see if any particular population may benefit from combination therapy compared to DOAC therapy alone.”

Dr. Schaefer reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Schaeffer J et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 787.

ORLANDO – in a large registry-based cohort.

The study, which involved a cohort of 2,045 patients who were followed at 6 anticoagulation clinics in Michigan during January 2009–June 2019, also found no apparent improvement in thrombosis incidence with the addition of aspirin, Jordan K. Schaefer, MD, reported during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Of the cohort patients, 639 adults who received a DOAC plus aspirin after VTE or for NVAF without a clear indication were compared with 639 propensity-matched controls. The bleeding event rate per 100 patient years was 39.50 vs. 32.32 at an average of 15.2 months of follow-up in the combination therapy and DOAC monotherapy groups, respectively, said Dr. Schaefer of the division of hematology/oncology, department of internal medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“This result was statistically significant for clinically relevant non-major bleeding, with an 18.7 rate per 100 patient years, compared with 13.5 for DOAC monotherapy,” (P = .02), he said. “We also saw a significant increase in non-major bleeding with combination therapy, compared with direct oral anticoagulant monotherapy” (rate, 32.82 vs. 25.88; P =.04).

No significant difference was seen overall (P =.07) or for other specific types of bleeding, he noted.

The observed rates of thrombosis in the groups, respectively, were 2.35 and 2.23 per 100 patient years (P =.95), he said, noting that patients on combination therapy also had more emergency department visits and hospitalizations, but those differences were not statistically significant.

“Direct-acting oral anticoagulants, which include apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban, are increasingly used in clinical practice for indications that include the prevention of strokes for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, and the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolic disease,” Dr. Schaefer said.

Aspirin is commonly used in clinical practice for various indications, including primary prevention of heart attacks, strokes, and colorectal cancer, as well as for thromboprophylaxis in patients with certain blood disorders or with certain cardiac devices, he added.

“Aspirin is used for the secondary prevention of thrombosis for patients with known coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, or carotid artery disease,” he said. “And while adding aspirin to a DOAC is often appropriate after acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous coronary intervention, many patients receive the combination therapy without a clear indication, he said, noting that increasing evidence in recent years, largely from patients treated with warfarin and aspirin, suggest that the approach may do more harm than good for certain patients.

Specifically, there’s a question of whether aspirin is increasing the rates of bleeding without protecting patients from adverse thrombotic outcomes.

“This has specifically been a concern for patients who are on full-dose anticoagulation,” he said.

In the current study, patient demographics, comorbidities, and concurrent medications were well balanced in the treatment and control groups after propensity score matching, he said, noting that patients with a history of heart valve replacement, recent MI, or less than 3 months of follow-up were excluded.

“These findings need to be confirmed in larger studies, but until such data [are] available, clinicians and patients should continue to balance the relative risks and benefits of adding aspirin to their direct oral anticoagulant therapy,” Dr. Schaefer said. “Further research needs to evaluate key subgroups to see if any particular population may benefit from combination therapy compared to DOAC therapy alone.”

Dr. Schaefer reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Schaeffer J et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 787.

ORLANDO – in a large registry-based cohort.

The study, which involved a cohort of 2,045 patients who were followed at 6 anticoagulation clinics in Michigan during January 2009–June 2019, also found no apparent improvement in thrombosis incidence with the addition of aspirin, Jordan K. Schaefer, MD, reported during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Of the cohort patients, 639 adults who received a DOAC plus aspirin after VTE or for NVAF without a clear indication were compared with 639 propensity-matched controls. The bleeding event rate per 100 patient years was 39.50 vs. 32.32 at an average of 15.2 months of follow-up in the combination therapy and DOAC monotherapy groups, respectively, said Dr. Schaefer of the division of hematology/oncology, department of internal medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“This result was statistically significant for clinically relevant non-major bleeding, with an 18.7 rate per 100 patient years, compared with 13.5 for DOAC monotherapy,” (P = .02), he said. “We also saw a significant increase in non-major bleeding with combination therapy, compared with direct oral anticoagulant monotherapy” (rate, 32.82 vs. 25.88; P =.04).

No significant difference was seen overall (P =.07) or for other specific types of bleeding, he noted.

The observed rates of thrombosis in the groups, respectively, were 2.35 and 2.23 per 100 patient years (P =.95), he said, noting that patients on combination therapy also had more emergency department visits and hospitalizations, but those differences were not statistically significant.

“Direct-acting oral anticoagulants, which include apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban, are increasingly used in clinical practice for indications that include the prevention of strokes for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, and the treatment and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolic disease,” Dr. Schaefer said.

Aspirin is commonly used in clinical practice for various indications, including primary prevention of heart attacks, strokes, and colorectal cancer, as well as for thromboprophylaxis in patients with certain blood disorders or with certain cardiac devices, he added.

“Aspirin is used for the secondary prevention of thrombosis for patients with known coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, or carotid artery disease,” he said. “And while adding aspirin to a DOAC is often appropriate after acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous coronary intervention, many patients receive the combination therapy without a clear indication, he said, noting that increasing evidence in recent years, largely from patients treated with warfarin and aspirin, suggest that the approach may do more harm than good for certain patients.

Specifically, there’s a question of whether aspirin is increasing the rates of bleeding without protecting patients from adverse thrombotic outcomes.

“This has specifically been a concern for patients who are on full-dose anticoagulation,” he said.

In the current study, patient demographics, comorbidities, and concurrent medications were well balanced in the treatment and control groups after propensity score matching, he said, noting that patients with a history of heart valve replacement, recent MI, or less than 3 months of follow-up were excluded.

“These findings need to be confirmed in larger studies, but until such data [are] available, clinicians and patients should continue to balance the relative risks and benefits of adding aspirin to their direct oral anticoagulant therapy,” Dr. Schaefer said. “Further research needs to evaluate key subgroups to see if any particular population may benefit from combination therapy compared to DOAC therapy alone.”

Dr. Schaefer reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Schaeffer J et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 787.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2019

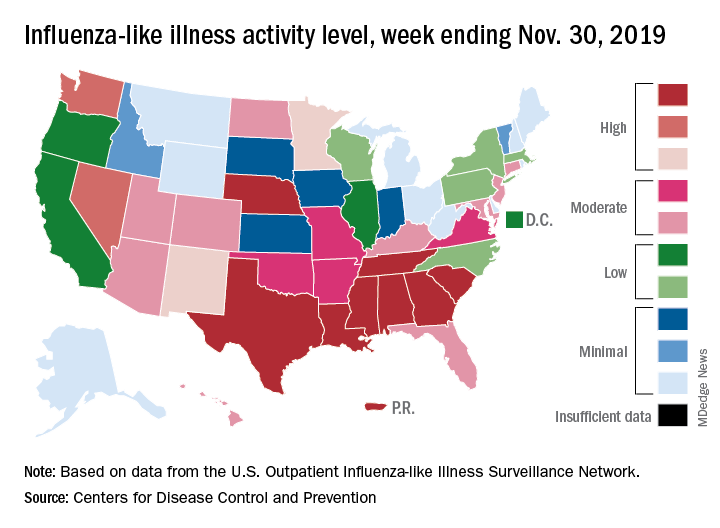

Influenza already in midseason form

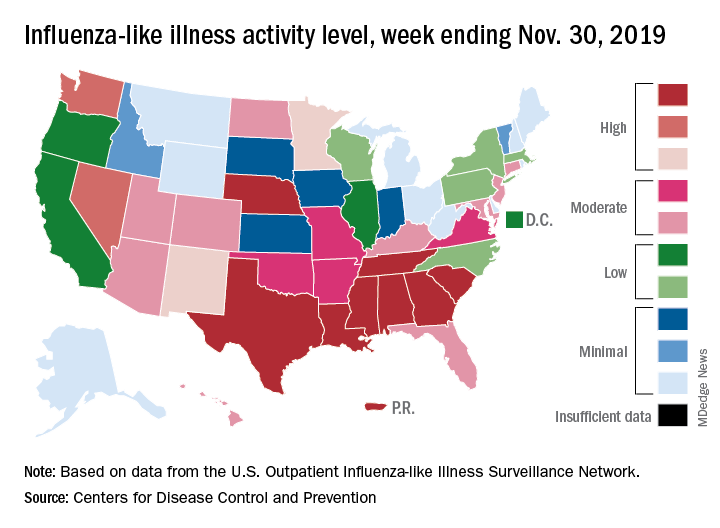

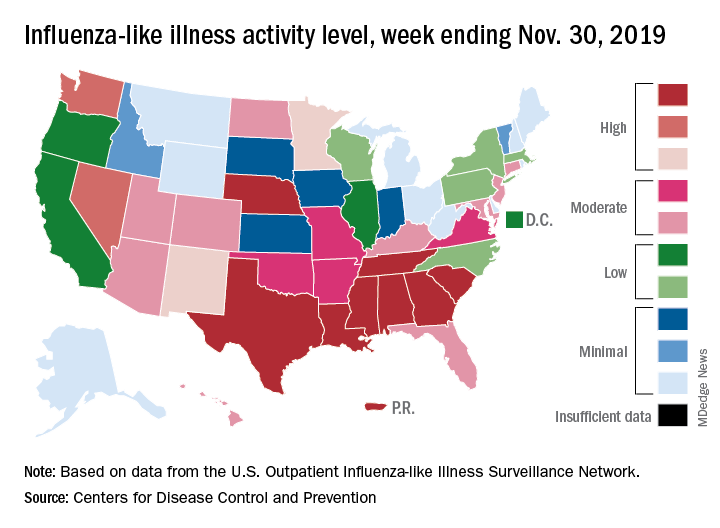

It’s been a decade since flu activity levels were this high this early in the season.

For the week ending Nov. 30, outpatient visits for influenza-like illness reached 3.5% of all visits to health care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 6. That is the highest pre-December rate since the pandemic of 2009-2010, when the rate peaked at 7.7% in mid-October, CDC data show.

For the last week of November, eight states and Puerto Rico reported activity levels at the high point of the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is at least five more states than any of the past five flu seasons. Three of the last five seasons had no states at level 10 this early in the season.

Another 4 states at levels 8 and 9 put a total of 13 jurisdictions in the “high” range of flu activity, with another 14 states in the “moderate” range of levels 6 and 7. Geographically speaking, 24 jurisdictions are experiencing regional or widespread activity, which is up from the 15 reported last week, the CDC’s influenza division said.

The hospitalization rate to date for the 2019-2020 season – 2.7 per 100,000 population – is “similar to what has been seen at this time during other recent seasons,” the CDC said.

One influenza-related pediatric death was reported during the week ending Nov. 30, which brings the total for the season to six, according to the CDC report.

It’s been a decade since flu activity levels were this high this early in the season.

For the week ending Nov. 30, outpatient visits for influenza-like illness reached 3.5% of all visits to health care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 6. That is the highest pre-December rate since the pandemic of 2009-2010, when the rate peaked at 7.7% in mid-October, CDC data show.

For the last week of November, eight states and Puerto Rico reported activity levels at the high point of the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is at least five more states than any of the past five flu seasons. Three of the last five seasons had no states at level 10 this early in the season.

Another 4 states at levels 8 and 9 put a total of 13 jurisdictions in the “high” range of flu activity, with another 14 states in the “moderate” range of levels 6 and 7. Geographically speaking, 24 jurisdictions are experiencing regional or widespread activity, which is up from the 15 reported last week, the CDC’s influenza division said.

The hospitalization rate to date for the 2019-2020 season – 2.7 per 100,000 population – is “similar to what has been seen at this time during other recent seasons,” the CDC said.

One influenza-related pediatric death was reported during the week ending Nov. 30, which brings the total for the season to six, according to the CDC report.

It’s been a decade since flu activity levels were this high this early in the season.

For the week ending Nov. 30, outpatient visits for influenza-like illness reached 3.5% of all visits to health care providers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported Dec. 6. That is the highest pre-December rate since the pandemic of 2009-2010, when the rate peaked at 7.7% in mid-October, CDC data show.

For the last week of November, eight states and Puerto Rico reported activity levels at the high point of the CDC’s 1-10 scale, which is at least five more states than any of the past five flu seasons. Three of the last five seasons had no states at level 10 this early in the season.

Another 4 states at levels 8 and 9 put a total of 13 jurisdictions in the “high” range of flu activity, with another 14 states in the “moderate” range of levels 6 and 7. Geographically speaking, 24 jurisdictions are experiencing regional or widespread activity, which is up from the 15 reported last week, the CDC’s influenza division said.

The hospitalization rate to date for the 2019-2020 season – 2.7 per 100,000 population – is “similar to what has been seen at this time during other recent seasons,” the CDC said.

One influenza-related pediatric death was reported during the week ending Nov. 30, which brings the total for the season to six, according to the CDC report.

Experts bring clarity to end of life difficulties

Understanding family perspective is an important factor

A Vietnam veteran steered clear of the health care system for years, then showed up at the hospital with pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was whisked to the intensive care unit, and cancerous masses were found.

The situation – as described by Jeffrey Frank, MD, director of quality and performance at Vituity, a physician group in Emeryville, Calif. – then got worse.

“No one was there for him,” Dr. Frank said. “He’s laying in the ICU, he does not have the capacity to make decisions, let alone communicate. So the care team needs guidance.”

Too often, hospitalists find themselves in confusing situations involving patients near the end of their lives, having to determine how to go about treating a patient or withholding treatment when patients are not in a position to announce their wishes. When family is present, the health care team thinks the most sensible course of treatment is at odds with what the family wants to be done.

At the Society of Hospital Medicine 2019 Annual Conference, hospitalists with palliative care training offered advice on how to go about handling these difficult situations, which can sometimes become more manageable with certain strategies.

For situations in which there is no designated representative to speak for a patient who is unresponsive – the so-called “unbefriended patient” or “unrepresented patient” – any source of information can be valuable. And health care providers should seek out this input, Dr. Frank said.

“When there is a visitor at the bedside, and as long as they know the person, and they can start giving the medical providers some information about what the patient would have wanted, most of us will talk with that person and that’s actually a good habit,” he said.

Thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have regulations on whom health care providers should talk to when there is no obvious representative, Dr. Frank said, noting that most of these regulations follow a classic family-tree order. But in the discouraging results of many surveys of health care providers on the subject, most clinicians say that they do not know the regulations in their state, Dr. Frank said. But he said such results betray a silver lining because clinicians say that they would be inclined to use a family tree–style hierarchy in deciding with whom they should speak about end of life decisions.

Hospitalists should at least know whether their hospital has a policy on unrepresented patients, Dr. Frank said.

“That’s your road map on how to get through consenting this patient – what am I going to do with Mr. Smith?” he said. “You may ask yourself, ‘Do I just keep treating him and treating him?’ If you have a policy at your hospital, it will protect you from liability, as well as give you a sense of process.”

Conflicts in communication

An even worse situation, perhaps, is one that many hospitalists have seen: A patient is teetering at the edge of life, and a spouse arrives, along with two daughters from out of state who have not seen their father in a year, said Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, director of the ethics curriculum at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“The family requests that the medical team do everything, including intubation and attempts at resuscitation if needed,” she said. “The family says he was fine prior to this admission. Another thing I hear a lot is, ‘He was even sicker than this last year, and he got better.’ ”

Meanwhile, “the medical team consensus is that he is not going to survive this illness,” Dr. Gundersen said.

The situation is so common and problematic that it has a name – the “Daughter from California Syndrome.” (According to medical literature says, it’s called the “Daughter from Chicago Syndrome” in California.)

“This is one of the most agonizing things that happens to us in medicine,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It affects us, it affects our nurses, it affects the entire medical team. It’s agonizing when we feel like treatment has somehow turned to torture.”

Dr. Gundersen said the medical staff should avoid using the word “futile,” or similar language, with families.

“Words matter,” she said. “Inappropriate language can inadvertently convey the feeling that, ‘They’re giving up on my dad – they think it’s hopeless.’ That can make families and the medical team dig in their heels further.”

Sometimes it can be hard to define the terms of decision making. Even if the family and the medical team can agree that no “nonbeneficial treatments” should be administered, Dr. Gundersen said, what exactly does that mean? Does it mean less than a 1% chance of working; less than a 5% chance?

If the medical staff thinks a mode of care won’t be effective, but the family still insists, some states have laws that could help the medical team. In Texas, for example, if the medical team thinks the care they’re giving isn’t helping the patient, and the patient is likely going to have a poor outcome, there’s a legal process that the team can go through, Dr. Gundersen said. But even these laws are seen as potentially problematic because of concerns that they put too much power in the hands of a hospital committee.

Dr. Gundersen strongly advised getting at the root causes of a family’s apprehension. They might not have been informed early enough about the dire nature of an illness to feel they can make a decision comfortably. They also may be receiving information in a piecemeal manner or information that is inconsistent. Another common fear expressed by families is a concern over abandonment by the medical team if a decision is made to forgo a certain treatment. Also, sometimes the goals of care might not be properly detailed and discussed, she said.

But better communication can help overcome these snags, Dr. Gundersen said.

She suggested that sometimes it’s helpful to clarify things with the family, for example, what do they mean by “Do everything”?

“Does it mean ‘I want you to do everything to prolong their life even if they suffer,’ or does it mean ‘I want you do to everything that’s reasonable to try to prolong their life but not at the risk of increased suffering,’ or anywhere in between. Really just having these clarifying conversations is helpful.”

She also emphasized the importance of talking about interests, such as not wanting a patient to suffer, instead of taking positions, such as flatly recommending the withdrawal of treatment.

“It’s easy for both sides to kind of dig in their heels and not communicate effectively,” Dr. Gundersen said.

‘Emotional torture’

There are times when, no matter how skillfully the medical team communicates, they stand at an impasse with the family.

“This is emotional torture for us,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It’s moral distress. We kind of dread these situations. In these cases, trying to support yourself and your team emotionally is the most important thing.”

Ami Doshi, MD, director of palliative care inpatient services at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, described the case of a baby girl that touched on the especially painful issues that can arise in pediatric cases. The 2-month-old girl had been born after a pregnancy affected by polyhydramnios and had an abnormal neurological exam and brain MRI, as well as congenital abnormalities. She’d been intubated for respiratory failure and was now on high-flow nasal cannula therapy. The girl was intolerant to feeding and was put on a nasojejunal feeding tube and then a gastrostomy-jejunostomy tube.

But the baby’s vomiting continued, and she had bradycardia and hypoxia so severe she needed bag mask ventilation to recover. The mother started to feel like she was “torturing” the baby.

The family decided to stop respiratory support but to continue artificial nutrition and hydration, which Dr. Doshi said, has an elevated status in the human psyche. Mentioning discontinuing feeding is fraught with complexity, she said.

“The notion of feeding is such a basic instinct, especially with a baby, that tackling the notion of discontinuing any sort of feeds, orally or tube feeds, is fraught with emotion and angst at times,” Dr. Doshi said.

The girl had respiratory events but recovered from them on her own, but the vomiting and retching continued. Eventually the artificial nutrition and hydration was stopped. But after 5 days, the medical staff began feeling uncomfortable, Dr. Doshi said. “We’re starting to hear from nurses, doctors, other people, that something just doesn’t feel right about what’s happening: ‘She seems okay,’ and, ‘Is it really okay for us to be doing this?’ and ‘Gosh, this is taking a long time.’ ”

The medical staff had, in a sense, joined the family on the emotional roller coaster.

Dr. Doshi said it’s important to remember that there is no ethical or moral distinction between withdrawing a medical intervention and withholding one.

“Stopping an intervention once it has started is no different ethically or legally than not starting it in the first place,” she said.

According to Dr. Doshi, there is a general consensus among medical societies that artificial nutrition and hydration is a medical intervention just like any other and that it should be evaluated within the same framework: Is it overly burdensome? Are we doing harm? Is it consistent with the goal of care? In so doing, be sure to respect patient autonomy and obtain informed consent.

As with so much in medicine, careful communication is a must.

“Paint a picture of what the patient’s trajectory is going to look like with and without artificial nutrition and hydration. At the end of the day, having done all of that, we’re going to ultimately respect what the patient or the surrogate decision maker decides,” Dr. Doshi said.

After assessment the data and the chances of success, and still without clarity about how to proceed, a good option might be considering a “time-limited trial” in which the medical team sits with the family and agrees on a time frame for an intervention and chooses predetermined endpoints for assessing success or failure.

“This can be very powerful to help us understand whether it is beneficial, but also – from the family’s perspective – to know everything was tried,” Dr. Doshi said.

Hospitalists should emphasize what is being added to treatment so that families don’t think only of what is being taken away, she said.

“Usually we are adding a lot – symptom management, a lot of psychosocial support. So what are all the other ways that we’re going to continue to care for the patient, even when we are withdrawing or withholding a specific intervention?” Dr. Doshi noted.

Sometimes, the best healer of distress in the midst of end of life decision making is time itself, Dr. Gundersen said.

In a condolence call, she once spoke with a family member involved in an agonizing case in which the medical team and family were at odds. Yet the man told her: “I know that you all were telling us the entire time that this was going to happen, but I guess we just had to go through our own process.”

Understanding family perspective is an important factor

Understanding family perspective is an important factor

A Vietnam veteran steered clear of the health care system for years, then showed up at the hospital with pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was whisked to the intensive care unit, and cancerous masses were found.

The situation – as described by Jeffrey Frank, MD, director of quality and performance at Vituity, a physician group in Emeryville, Calif. – then got worse.

“No one was there for him,” Dr. Frank said. “He’s laying in the ICU, he does not have the capacity to make decisions, let alone communicate. So the care team needs guidance.”

Too often, hospitalists find themselves in confusing situations involving patients near the end of their lives, having to determine how to go about treating a patient or withholding treatment when patients are not in a position to announce their wishes. When family is present, the health care team thinks the most sensible course of treatment is at odds with what the family wants to be done.

At the Society of Hospital Medicine 2019 Annual Conference, hospitalists with palliative care training offered advice on how to go about handling these difficult situations, which can sometimes become more manageable with certain strategies.

For situations in which there is no designated representative to speak for a patient who is unresponsive – the so-called “unbefriended patient” or “unrepresented patient” – any source of information can be valuable. And health care providers should seek out this input, Dr. Frank said.

“When there is a visitor at the bedside, and as long as they know the person, and they can start giving the medical providers some information about what the patient would have wanted, most of us will talk with that person and that’s actually a good habit,” he said.

Thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have regulations on whom health care providers should talk to when there is no obvious representative, Dr. Frank said, noting that most of these regulations follow a classic family-tree order. But in the discouraging results of many surveys of health care providers on the subject, most clinicians say that they do not know the regulations in their state, Dr. Frank said. But he said such results betray a silver lining because clinicians say that they would be inclined to use a family tree–style hierarchy in deciding with whom they should speak about end of life decisions.

Hospitalists should at least know whether their hospital has a policy on unrepresented patients, Dr. Frank said.

“That’s your road map on how to get through consenting this patient – what am I going to do with Mr. Smith?” he said. “You may ask yourself, ‘Do I just keep treating him and treating him?’ If you have a policy at your hospital, it will protect you from liability, as well as give you a sense of process.”

Conflicts in communication

An even worse situation, perhaps, is one that many hospitalists have seen: A patient is teetering at the edge of life, and a spouse arrives, along with two daughters from out of state who have not seen their father in a year, said Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, director of the ethics curriculum at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“The family requests that the medical team do everything, including intubation and attempts at resuscitation if needed,” she said. “The family says he was fine prior to this admission. Another thing I hear a lot is, ‘He was even sicker than this last year, and he got better.’ ”

Meanwhile, “the medical team consensus is that he is not going to survive this illness,” Dr. Gundersen said.

The situation is so common and problematic that it has a name – the “Daughter from California Syndrome.” (According to medical literature says, it’s called the “Daughter from Chicago Syndrome” in California.)

“This is one of the most agonizing things that happens to us in medicine,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It affects us, it affects our nurses, it affects the entire medical team. It’s agonizing when we feel like treatment has somehow turned to torture.”

Dr. Gundersen said the medical staff should avoid using the word “futile,” or similar language, with families.

“Words matter,” she said. “Inappropriate language can inadvertently convey the feeling that, ‘They’re giving up on my dad – they think it’s hopeless.’ That can make families and the medical team dig in their heels further.”

Sometimes it can be hard to define the terms of decision making. Even if the family and the medical team can agree that no “nonbeneficial treatments” should be administered, Dr. Gundersen said, what exactly does that mean? Does it mean less than a 1% chance of working; less than a 5% chance?

If the medical staff thinks a mode of care won’t be effective, but the family still insists, some states have laws that could help the medical team. In Texas, for example, if the medical team thinks the care they’re giving isn’t helping the patient, and the patient is likely going to have a poor outcome, there’s a legal process that the team can go through, Dr. Gundersen said. But even these laws are seen as potentially problematic because of concerns that they put too much power in the hands of a hospital committee.

Dr. Gundersen strongly advised getting at the root causes of a family’s apprehension. They might not have been informed early enough about the dire nature of an illness to feel they can make a decision comfortably. They also may be receiving information in a piecemeal manner or information that is inconsistent. Another common fear expressed by families is a concern over abandonment by the medical team if a decision is made to forgo a certain treatment. Also, sometimes the goals of care might not be properly detailed and discussed, she said.

But better communication can help overcome these snags, Dr. Gundersen said.

She suggested that sometimes it’s helpful to clarify things with the family, for example, what do they mean by “Do everything”?

“Does it mean ‘I want you to do everything to prolong their life even if they suffer,’ or does it mean ‘I want you do to everything that’s reasonable to try to prolong their life but not at the risk of increased suffering,’ or anywhere in between. Really just having these clarifying conversations is helpful.”

She also emphasized the importance of talking about interests, such as not wanting a patient to suffer, instead of taking positions, such as flatly recommending the withdrawal of treatment.

“It’s easy for both sides to kind of dig in their heels and not communicate effectively,” Dr. Gundersen said.

‘Emotional torture’

There are times when, no matter how skillfully the medical team communicates, they stand at an impasse with the family.

“This is emotional torture for us,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It’s moral distress. We kind of dread these situations. In these cases, trying to support yourself and your team emotionally is the most important thing.”

Ami Doshi, MD, director of palliative care inpatient services at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, described the case of a baby girl that touched on the especially painful issues that can arise in pediatric cases. The 2-month-old girl had been born after a pregnancy affected by polyhydramnios and had an abnormal neurological exam and brain MRI, as well as congenital abnormalities. She’d been intubated for respiratory failure and was now on high-flow nasal cannula therapy. The girl was intolerant to feeding and was put on a nasojejunal feeding tube and then a gastrostomy-jejunostomy tube.

But the baby’s vomiting continued, and she had bradycardia and hypoxia so severe she needed bag mask ventilation to recover. The mother started to feel like she was “torturing” the baby.

The family decided to stop respiratory support but to continue artificial nutrition and hydration, which Dr. Doshi said, has an elevated status in the human psyche. Mentioning discontinuing feeding is fraught with complexity, she said.

“The notion of feeding is such a basic instinct, especially with a baby, that tackling the notion of discontinuing any sort of feeds, orally or tube feeds, is fraught with emotion and angst at times,” Dr. Doshi said.

The girl had respiratory events but recovered from them on her own, but the vomiting and retching continued. Eventually the artificial nutrition and hydration was stopped. But after 5 days, the medical staff began feeling uncomfortable, Dr. Doshi said. “We’re starting to hear from nurses, doctors, other people, that something just doesn’t feel right about what’s happening: ‘She seems okay,’ and, ‘Is it really okay for us to be doing this?’ and ‘Gosh, this is taking a long time.’ ”

The medical staff had, in a sense, joined the family on the emotional roller coaster.

Dr. Doshi said it’s important to remember that there is no ethical or moral distinction between withdrawing a medical intervention and withholding one.

“Stopping an intervention once it has started is no different ethically or legally than not starting it in the first place,” she said.

According to Dr. Doshi, there is a general consensus among medical societies that artificial nutrition and hydration is a medical intervention just like any other and that it should be evaluated within the same framework: Is it overly burdensome? Are we doing harm? Is it consistent with the goal of care? In so doing, be sure to respect patient autonomy and obtain informed consent.

As with so much in medicine, careful communication is a must.

“Paint a picture of what the patient’s trajectory is going to look like with and without artificial nutrition and hydration. At the end of the day, having done all of that, we’re going to ultimately respect what the patient or the surrogate decision maker decides,” Dr. Doshi said.

After assessment the data and the chances of success, and still without clarity about how to proceed, a good option might be considering a “time-limited trial” in which the medical team sits with the family and agrees on a time frame for an intervention and chooses predetermined endpoints for assessing success or failure.

“This can be very powerful to help us understand whether it is beneficial, but also – from the family’s perspective – to know everything was tried,” Dr. Doshi said.

Hospitalists should emphasize what is being added to treatment so that families don’t think only of what is being taken away, she said.

“Usually we are adding a lot – symptom management, a lot of psychosocial support. So what are all the other ways that we’re going to continue to care for the patient, even when we are withdrawing or withholding a specific intervention?” Dr. Doshi noted.

Sometimes, the best healer of distress in the midst of end of life decision making is time itself, Dr. Gundersen said.

In a condolence call, she once spoke with a family member involved in an agonizing case in which the medical team and family were at odds. Yet the man told her: “I know that you all were telling us the entire time that this was going to happen, but I guess we just had to go through our own process.”

A Vietnam veteran steered clear of the health care system for years, then showed up at the hospital with pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was whisked to the intensive care unit, and cancerous masses were found.

The situation – as described by Jeffrey Frank, MD, director of quality and performance at Vituity, a physician group in Emeryville, Calif. – then got worse.

“No one was there for him,” Dr. Frank said. “He’s laying in the ICU, he does not have the capacity to make decisions, let alone communicate. So the care team needs guidance.”

Too often, hospitalists find themselves in confusing situations involving patients near the end of their lives, having to determine how to go about treating a patient or withholding treatment when patients are not in a position to announce their wishes. When family is present, the health care team thinks the most sensible course of treatment is at odds with what the family wants to be done.

At the Society of Hospital Medicine 2019 Annual Conference, hospitalists with palliative care training offered advice on how to go about handling these difficult situations, which can sometimes become more manageable with certain strategies.

For situations in which there is no designated representative to speak for a patient who is unresponsive – the so-called “unbefriended patient” or “unrepresented patient” – any source of information can be valuable. And health care providers should seek out this input, Dr. Frank said.

“When there is a visitor at the bedside, and as long as they know the person, and they can start giving the medical providers some information about what the patient would have wanted, most of us will talk with that person and that’s actually a good habit,” he said.

Thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have regulations on whom health care providers should talk to when there is no obvious representative, Dr. Frank said, noting that most of these regulations follow a classic family-tree order. But in the discouraging results of many surveys of health care providers on the subject, most clinicians say that they do not know the regulations in their state, Dr. Frank said. But he said such results betray a silver lining because clinicians say that they would be inclined to use a family tree–style hierarchy in deciding with whom they should speak about end of life decisions.

Hospitalists should at least know whether their hospital has a policy on unrepresented patients, Dr. Frank said.

“That’s your road map on how to get through consenting this patient – what am I going to do with Mr. Smith?” he said. “You may ask yourself, ‘Do I just keep treating him and treating him?’ If you have a policy at your hospital, it will protect you from liability, as well as give you a sense of process.”

Conflicts in communication

An even worse situation, perhaps, is one that many hospitalists have seen: A patient is teetering at the edge of life, and a spouse arrives, along with two daughters from out of state who have not seen their father in a year, said Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, director of the ethics curriculum at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“The family requests that the medical team do everything, including intubation and attempts at resuscitation if needed,” she said. “The family says he was fine prior to this admission. Another thing I hear a lot is, ‘He was even sicker than this last year, and he got better.’ ”

Meanwhile, “the medical team consensus is that he is not going to survive this illness,” Dr. Gundersen said.

The situation is so common and problematic that it has a name – the “Daughter from California Syndrome.” (According to medical literature says, it’s called the “Daughter from Chicago Syndrome” in California.)

“This is one of the most agonizing things that happens to us in medicine,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It affects us, it affects our nurses, it affects the entire medical team. It’s agonizing when we feel like treatment has somehow turned to torture.”

Dr. Gundersen said the medical staff should avoid using the word “futile,” or similar language, with families.

“Words matter,” she said. “Inappropriate language can inadvertently convey the feeling that, ‘They’re giving up on my dad – they think it’s hopeless.’ That can make families and the medical team dig in their heels further.”

Sometimes it can be hard to define the terms of decision making. Even if the family and the medical team can agree that no “nonbeneficial treatments” should be administered, Dr. Gundersen said, what exactly does that mean? Does it mean less than a 1% chance of working; less than a 5% chance?

If the medical staff thinks a mode of care won’t be effective, but the family still insists, some states have laws that could help the medical team. In Texas, for example, if the medical team thinks the care they’re giving isn’t helping the patient, and the patient is likely going to have a poor outcome, there’s a legal process that the team can go through, Dr. Gundersen said. But even these laws are seen as potentially problematic because of concerns that they put too much power in the hands of a hospital committee.

Dr. Gundersen strongly advised getting at the root causes of a family’s apprehension. They might not have been informed early enough about the dire nature of an illness to feel they can make a decision comfortably. They also may be receiving information in a piecemeal manner or information that is inconsistent. Another common fear expressed by families is a concern over abandonment by the medical team if a decision is made to forgo a certain treatment. Also, sometimes the goals of care might not be properly detailed and discussed, she said.

But better communication can help overcome these snags, Dr. Gundersen said.

She suggested that sometimes it’s helpful to clarify things with the family, for example, what do they mean by “Do everything”?

“Does it mean ‘I want you to do everything to prolong their life even if they suffer,’ or does it mean ‘I want you do to everything that’s reasonable to try to prolong their life but not at the risk of increased suffering,’ or anywhere in between. Really just having these clarifying conversations is helpful.”

She also emphasized the importance of talking about interests, such as not wanting a patient to suffer, instead of taking positions, such as flatly recommending the withdrawal of treatment.

“It’s easy for both sides to kind of dig in their heels and not communicate effectively,” Dr. Gundersen said.

‘Emotional torture’

There are times when, no matter how skillfully the medical team communicates, they stand at an impasse with the family.

“This is emotional torture for us,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It’s moral distress. We kind of dread these situations. In these cases, trying to support yourself and your team emotionally is the most important thing.”

Ami Doshi, MD, director of palliative care inpatient services at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, described the case of a baby girl that touched on the especially painful issues that can arise in pediatric cases. The 2-month-old girl had been born after a pregnancy affected by polyhydramnios and had an abnormal neurological exam and brain MRI, as well as congenital abnormalities. She’d been intubated for respiratory failure and was now on high-flow nasal cannula therapy. The girl was intolerant to feeding and was put on a nasojejunal feeding tube and then a gastrostomy-jejunostomy tube.

But the baby’s vomiting continued, and she had bradycardia and hypoxia so severe she needed bag mask ventilation to recover. The mother started to feel like she was “torturing” the baby.

The family decided to stop respiratory support but to continue artificial nutrition and hydration, which Dr. Doshi said, has an elevated status in the human psyche. Mentioning discontinuing feeding is fraught with complexity, she said.

“The notion of feeding is such a basic instinct, especially with a baby, that tackling the notion of discontinuing any sort of feeds, orally or tube feeds, is fraught with emotion and angst at times,” Dr. Doshi said.

The girl had respiratory events but recovered from them on her own, but the vomiting and retching continued. Eventually the artificial nutrition and hydration was stopped. But after 5 days, the medical staff began feeling uncomfortable, Dr. Doshi said. “We’re starting to hear from nurses, doctors, other people, that something just doesn’t feel right about what’s happening: ‘She seems okay,’ and, ‘Is it really okay for us to be doing this?’ and ‘Gosh, this is taking a long time.’ ”

The medical staff had, in a sense, joined the family on the emotional roller coaster.

Dr. Doshi said it’s important to remember that there is no ethical or moral distinction between withdrawing a medical intervention and withholding one.

“Stopping an intervention once it has started is no different ethically or legally than not starting it in the first place,” she said.

According to Dr. Doshi, there is a general consensus among medical societies that artificial nutrition and hydration is a medical intervention just like any other and that it should be evaluated within the same framework: Is it overly burdensome? Are we doing harm? Is it consistent with the goal of care? In so doing, be sure to respect patient autonomy and obtain informed consent.

As with so much in medicine, careful communication is a must.

“Paint a picture of what the patient’s trajectory is going to look like with and without artificial nutrition and hydration. At the end of the day, having done all of that, we’re going to ultimately respect what the patient or the surrogate decision maker decides,” Dr. Doshi said.

After assessment the data and the chances of success, and still without clarity about how to proceed, a good option might be considering a “time-limited trial” in which the medical team sits with the family and agrees on a time frame for an intervention and chooses predetermined endpoints for assessing success or failure.

“This can be very powerful to help us understand whether it is beneficial, but also – from the family’s perspective – to know everything was tried,” Dr. Doshi said.

Hospitalists should emphasize what is being added to treatment so that families don’t think only of what is being taken away, she said.

“Usually we are adding a lot – symptom management, a lot of psychosocial support. So what are all the other ways that we’re going to continue to care for the patient, even when we are withdrawing or withholding a specific intervention?” Dr. Doshi noted.

Sometimes, the best healer of distress in the midst of end of life decision making is time itself, Dr. Gundersen said.

In a condolence call, she once spoke with a family member involved in an agonizing case in which the medical team and family were at odds. Yet the man told her: “I know that you all were telling us the entire time that this was going to happen, but I guess we just had to go through our own process.”

Gunshot wound victims are at high risk for readmission

CHICAGO –

A study of individuals at a single institution who were hospitalized and had a prior history of gunshot wound found some patterns of injury that set patients up for a greater likelihood of readmission.

In particular, patients who sustained visceral gunshot wounds were over six times more likely to be readmitted to the hospital, Corbin Pomeranz, MD, a radiology resident at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. Dr. Pomeranz led the retrospective study that begins to fill a knowledge gap about what happens over the long term to those who sustain gunshot wounds.

“There continues to be profound lack of substantial information related to gun violence, particularly in predicting long-term outcomes,” Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

The researchers performed a single-site retrospective analysis over 3 months in 2018, tapping into an imaging database and looking for inpatient imaging exams that were nonacute, but related to gunshot wounds. From this information, the researchers went back to the original gunshot wound injury imaging, and recorded the pattern of injury, classifying wounds as neurologic, vascular, visceral, musculoskeletal, or involving multiple systems.

The investigators were able to glean additional information including the initial admitting hospital unit, information about interval admissions or surgeries, and demographic data. Regarding the nature of the gunshot injury itself, Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors went back to the earlier imaging studies to note bullet morphology, recording whether the bullet was intact, deformed, or had splintered into shrapnel within injured tissues.

In all, 174 imaging studies involving 110 patients were examined. Men made up 92% of the study population; the average age was 49.7 years. Neurologic and visceral gunshot wounds were moderately correlated with subsequent readmission (r = .436; P less than .001). However, some of this effect was blunted when patient age was controlled for in the statistical analysis.

Patients who were initially admitted to the intensive care unit, and who presumably had more severe injuries, were also more likely to be readmitted (r = .494, P less than .001). Here, “controlling for age had very little effect on the strength of the relationship between these two variables,” noted Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors.

A more elaborate statistical model incorporated several independent variables including age, type of injury, and body region involved, as well as bullet morphology. In this model, visceral injury was the strongest predictor for readmission, with an odds ratio of 6.44.

Dr. Pomeranz said that both the initial gunshot wound and subsequent gaps in care can contribute to readmissions. A patient who has a spinal cord injury may not be reimbursed adequately for supportive cushioning, or an appropriate wheelchair, and so may require admission for decubitus ulcers.

The number of admissions for osteomyelitis, which made up more than half of the subsequent admissions, initially surprised Dr. Pomeranz, until he realized that lack of mobility and sensory losses from gunshot-induced spinal cord injuries could easily lead to nonhealing lower extremity wounds, with osteomyelitis as a sequela.

Several patients were admitted for small bowel obstructions with no interval surgery since treatment for the gunshot wound. These readmissions, said Dr. Pomeranz, were assessed as related to the gunshot wound since it’s extremely rare for a patient with no history of abdominal surgery and no malignancy to have a small bowel obstruction. Exploratory laparotomies are common in the context of abdominal trauma caused by gunshot wounds, and either the gunshot itself or the laparotomy was the likely cause of adhesions.

Dr. Pomeranz acknowledged the many limitations of the study, but pointed out that some will be addressed when he and his coauthors conduct a larger study they have planned to look at readmissions from gunshot wounds at multiple hospitals in the Philadelphia area. The small sample size in the current study meant that the impact of socioeconomic status and other lifestyle and social variables and comorbidities couldn’t be adequately addressed in the statistical analysis. By casting a wider net within the greater Philadelphia area, the investigators should be able to track patients who receive care in more than one hospital system, increasing participant numbers, he said.

“Morbidity and outcomes from gun violence can only be assessed after a firm understanding of injury patterns on imaging,” noted Dr. Pomeranz. He said that interdisciplinary research investigating individual and societal short- and long-term costs of gun violence is sorely needed to inform public policy.

Dr. Pomeranz reported no outside sources of funding and reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pomeranz C et al. RSNA 2019, Presentation HP226-SD-THA3.

CHICAGO –

A study of individuals at a single institution who were hospitalized and had a prior history of gunshot wound found some patterns of injury that set patients up for a greater likelihood of readmission.

In particular, patients who sustained visceral gunshot wounds were over six times more likely to be readmitted to the hospital, Corbin Pomeranz, MD, a radiology resident at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. Dr. Pomeranz led the retrospective study that begins to fill a knowledge gap about what happens over the long term to those who sustain gunshot wounds.

“There continues to be profound lack of substantial information related to gun violence, particularly in predicting long-term outcomes,” Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

The researchers performed a single-site retrospective analysis over 3 months in 2018, tapping into an imaging database and looking for inpatient imaging exams that were nonacute, but related to gunshot wounds. From this information, the researchers went back to the original gunshot wound injury imaging, and recorded the pattern of injury, classifying wounds as neurologic, vascular, visceral, musculoskeletal, or involving multiple systems.

The investigators were able to glean additional information including the initial admitting hospital unit, information about interval admissions or surgeries, and demographic data. Regarding the nature of the gunshot injury itself, Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors went back to the earlier imaging studies to note bullet morphology, recording whether the bullet was intact, deformed, or had splintered into shrapnel within injured tissues.

In all, 174 imaging studies involving 110 patients were examined. Men made up 92% of the study population; the average age was 49.7 years. Neurologic and visceral gunshot wounds were moderately correlated with subsequent readmission (r = .436; P less than .001). However, some of this effect was blunted when patient age was controlled for in the statistical analysis.

Patients who were initially admitted to the intensive care unit, and who presumably had more severe injuries, were also more likely to be readmitted (r = .494, P less than .001). Here, “controlling for age had very little effect on the strength of the relationship between these two variables,” noted Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors.

A more elaborate statistical model incorporated several independent variables including age, type of injury, and body region involved, as well as bullet morphology. In this model, visceral injury was the strongest predictor for readmission, with an odds ratio of 6.44.

Dr. Pomeranz said that both the initial gunshot wound and subsequent gaps in care can contribute to readmissions. A patient who has a spinal cord injury may not be reimbursed adequately for supportive cushioning, or an appropriate wheelchair, and so may require admission for decubitus ulcers.

The number of admissions for osteomyelitis, which made up more than half of the subsequent admissions, initially surprised Dr. Pomeranz, until he realized that lack of mobility and sensory losses from gunshot-induced spinal cord injuries could easily lead to nonhealing lower extremity wounds, with osteomyelitis as a sequela.

Several patients were admitted for small bowel obstructions with no interval surgery since treatment for the gunshot wound. These readmissions, said Dr. Pomeranz, were assessed as related to the gunshot wound since it’s extremely rare for a patient with no history of abdominal surgery and no malignancy to have a small bowel obstruction. Exploratory laparotomies are common in the context of abdominal trauma caused by gunshot wounds, and either the gunshot itself or the laparotomy was the likely cause of adhesions.

Dr. Pomeranz acknowledged the many limitations of the study, but pointed out that some will be addressed when he and his coauthors conduct a larger study they have planned to look at readmissions from gunshot wounds at multiple hospitals in the Philadelphia area. The small sample size in the current study meant that the impact of socioeconomic status and other lifestyle and social variables and comorbidities couldn’t be adequately addressed in the statistical analysis. By casting a wider net within the greater Philadelphia area, the investigators should be able to track patients who receive care in more than one hospital system, increasing participant numbers, he said.

“Morbidity and outcomes from gun violence can only be assessed after a firm understanding of injury patterns on imaging,” noted Dr. Pomeranz. He said that interdisciplinary research investigating individual and societal short- and long-term costs of gun violence is sorely needed to inform public policy.

Dr. Pomeranz reported no outside sources of funding and reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pomeranz C et al. RSNA 2019, Presentation HP226-SD-THA3.

CHICAGO –

A study of individuals at a single institution who were hospitalized and had a prior history of gunshot wound found some patterns of injury that set patients up for a greater likelihood of readmission.

In particular, patients who sustained visceral gunshot wounds were over six times more likely to be readmitted to the hospital, Corbin Pomeranz, MD, a radiology resident at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America. Dr. Pomeranz led the retrospective study that begins to fill a knowledge gap about what happens over the long term to those who sustain gunshot wounds.

“There continues to be profound lack of substantial information related to gun violence, particularly in predicting long-term outcomes,” Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors wrote in the abstract accompanying the presentation.

The researchers performed a single-site retrospective analysis over 3 months in 2018, tapping into an imaging database and looking for inpatient imaging exams that were nonacute, but related to gunshot wounds. From this information, the researchers went back to the original gunshot wound injury imaging, and recorded the pattern of injury, classifying wounds as neurologic, vascular, visceral, musculoskeletal, or involving multiple systems.

The investigators were able to glean additional information including the initial admitting hospital unit, information about interval admissions or surgeries, and demographic data. Regarding the nature of the gunshot injury itself, Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors went back to the earlier imaging studies to note bullet morphology, recording whether the bullet was intact, deformed, or had splintered into shrapnel within injured tissues.

In all, 174 imaging studies involving 110 patients were examined. Men made up 92% of the study population; the average age was 49.7 years. Neurologic and visceral gunshot wounds were moderately correlated with subsequent readmission (r = .436; P less than .001). However, some of this effect was blunted when patient age was controlled for in the statistical analysis.

Patients who were initially admitted to the intensive care unit, and who presumably had more severe injuries, were also more likely to be readmitted (r = .494, P less than .001). Here, “controlling for age had very little effect on the strength of the relationship between these two variables,” noted Dr. Pomeranz and coauthors.

A more elaborate statistical model incorporated several independent variables including age, type of injury, and body region involved, as well as bullet morphology. In this model, visceral injury was the strongest predictor for readmission, with an odds ratio of 6.44.

Dr. Pomeranz said that both the initial gunshot wound and subsequent gaps in care can contribute to readmissions. A patient who has a spinal cord injury may not be reimbursed adequately for supportive cushioning, or an appropriate wheelchair, and so may require admission for decubitus ulcers.

The number of admissions for osteomyelitis, which made up more than half of the subsequent admissions, initially surprised Dr. Pomeranz, until he realized that lack of mobility and sensory losses from gunshot-induced spinal cord injuries could easily lead to nonhealing lower extremity wounds, with osteomyelitis as a sequela.

Several patients were admitted for small bowel obstructions with no interval surgery since treatment for the gunshot wound. These readmissions, said Dr. Pomeranz, were assessed as related to the gunshot wound since it’s extremely rare for a patient with no history of abdominal surgery and no malignancy to have a small bowel obstruction. Exploratory laparotomies are common in the context of abdominal trauma caused by gunshot wounds, and either the gunshot itself or the laparotomy was the likely cause of adhesions.

Dr. Pomeranz acknowledged the many limitations of the study, but pointed out that some will be addressed when he and his coauthors conduct a larger study they have planned to look at readmissions from gunshot wounds at multiple hospitals in the Philadelphia area. The small sample size in the current study meant that the impact of socioeconomic status and other lifestyle and social variables and comorbidities couldn’t be adequately addressed in the statistical analysis. By casting a wider net within the greater Philadelphia area, the investigators should be able to track patients who receive care in more than one hospital system, increasing participant numbers, he said.

“Morbidity and outcomes from gun violence can only be assessed after a firm understanding of injury patterns on imaging,” noted Dr. Pomeranz. He said that interdisciplinary research investigating individual and societal short- and long-term costs of gun violence is sorely needed to inform public policy.

Dr. Pomeranz reported no outside sources of funding and reported that he had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pomeranz C et al. RSNA 2019, Presentation HP226-SD-THA3.

REPORTING FROM RSNA 2019

2019-2020 flu season starts off full throttle

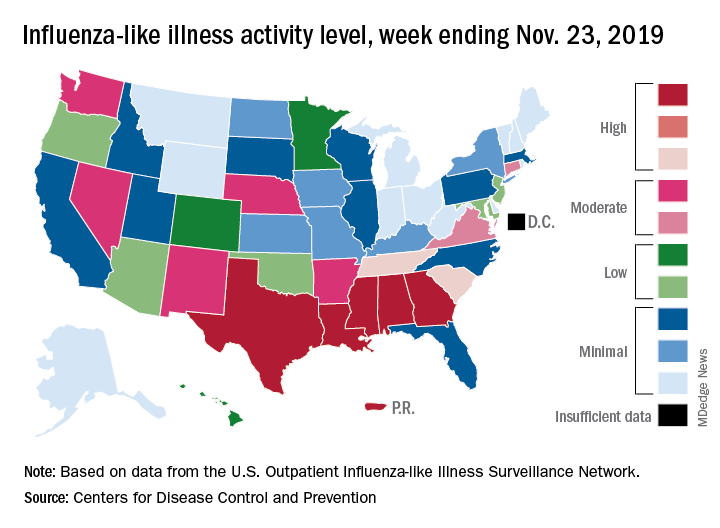

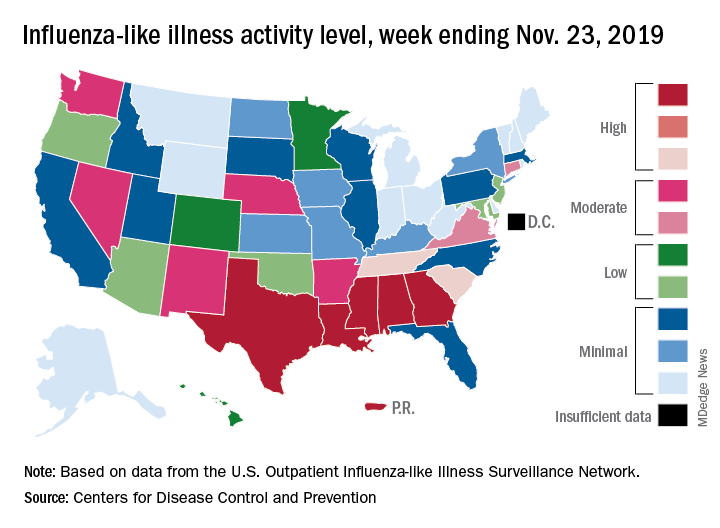

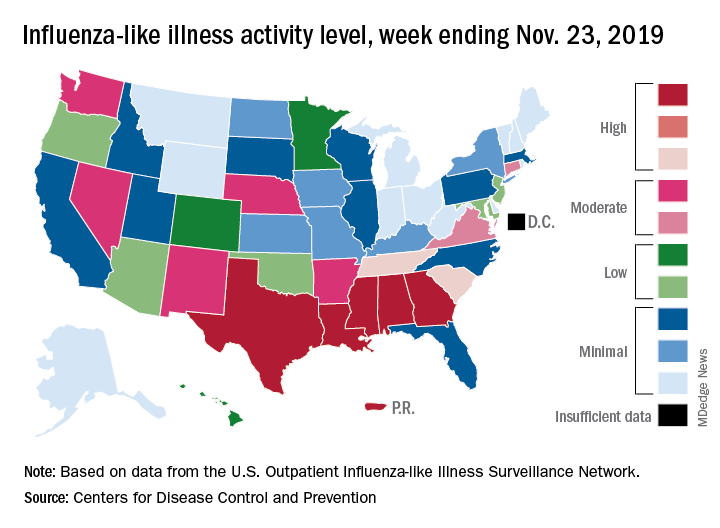

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

For the week ending Nov. 23, there were five states, along with Puerto Rico, at the highest level of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 1-10 scale of flu activity. That’s more than any year since 2012, including the pandemic season of 2017-2018, according to CDC data, and may suggest either an early peak or the beginning of a particularly bad winter.

“Nationally, ILI [influenza-like illness] activity has been at or above baseline for 3 weeks; however, the amount of influenza activity across the country varies with the south and parts of the west seeing elevated activity while other parts of the country are still seeing low activity,” the CDC’s influenza division said in its weekly FluView report.

The five highest-activity states – Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas – are all at level 10, and they join two others – South Carolina and Tennessee, which are at level 8 – in the “high” range from 8-10 on the ILI activity scale; Puerto Rico also is at level 10. ILI is defined as “fever (temperature of 100° F [37.8° C] or greater) and a cough and/or a sore throat without a known cause other than influenza,” the CDC said.

The activity scale is based on the percentage of outpatient visits for ILI in each state, which is reported to the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) each week. The national rate for the week ending Nov. 23 was 2.9%, which is above the new-for-this-season baseline rate of 2.4%. For the three previous flu seasons, the national baseline was 2.2%, having been raised from its previous level of 2.1% in 2015-2016, CDC data show.

The peak month of flu activity occurs most often in February – 15 times from 1982-1983 to 2017-2018 – but there were seven peaks in December and six each in January and March over that time period, along with one peak each in October and November, the CDC said. The October peak occurred during the H1N1 pandemic year of 2009, when the national outpatient ILI rate climbed to just over 7.7%.

Anticipating the A.I. revolution

Goal is to augment human performance

Artificial intelligence (A.I.) is likely to change almost everything in medical practice, according to a new book called “Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again,” by Eric Topol, MD.

Dr. Topol told The Hospitalist that his book’s subtitle “is the paradox: the unexpected, far-reaching goal of A.I. that can, if used properly, restore the most important part of medicine – a deep patient-doctor relationship.”

That’s because A.I. can do more than enhance diagnoses; it can also help with tasks such as note-taking and reading scans, making it possible for hospitalists to spend more time connecting with their patients. “Hospitalists could have a much better handle on a patient’s dataset via algorithmic processing, providing alerts and augmented performance of hospitalists (when validated),” Dr. Topol said. “They can also expect far less keyboard use with the help of speech recognition, natural language processing, and deep learning.”In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Topol said that by augmenting human performance, A.I. has the potential to markedly improve productivity, efficiency, work flow, accuracy and speed, both for doctors and for patients, giving more charge and control to consumers through algorithmic support of their data.

“We can’t, and will never, rely on only algorithms for interpretation of life and death matters,” he said. “That requires human expert contextualization, something machines can’t do.”Of course, there could be pitfalls. “The liabilities include breaches of privacy and security, hacking, the lack of explainability of most A.I. algorithms, the potential to worsen inequities, the embedded bias, and ethical quandaries,” he said.

Reference

1. O’Connor A. How Artificial Intelligence Could Transform Medicine. New York Times. March 11, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/11/well/live/how-artificial-intelligence-could-transform-medicine.html.

Goal is to augment human performance

Goal is to augment human performance

Artificial intelligence (A.I.) is likely to change almost everything in medical practice, according to a new book called “Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again,” by Eric Topol, MD.

Dr. Topol told The Hospitalist that his book’s subtitle “is the paradox: the unexpected, far-reaching goal of A.I. that can, if used properly, restore the most important part of medicine – a deep patient-doctor relationship.”

That’s because A.I. can do more than enhance diagnoses; it can also help with tasks such as note-taking and reading scans, making it possible for hospitalists to spend more time connecting with their patients. “Hospitalists could have a much better handle on a patient’s dataset via algorithmic processing, providing alerts and augmented performance of hospitalists (when validated),” Dr. Topol said. “They can also expect far less keyboard use with the help of speech recognition, natural language processing, and deep learning.”In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Topol said that by augmenting human performance, A.I. has the potential to markedly improve productivity, efficiency, work flow, accuracy and speed, both for doctors and for patients, giving more charge and control to consumers through algorithmic support of their data.

“We can’t, and will never, rely on only algorithms for interpretation of life and death matters,” he said. “That requires human expert contextualization, something machines can’t do.”Of course, there could be pitfalls. “The liabilities include breaches of privacy and security, hacking, the lack of explainability of most A.I. algorithms, the potential to worsen inequities, the embedded bias, and ethical quandaries,” he said.

Reference

1. O’Connor A. How Artificial Intelligence Could Transform Medicine. New York Times. March 11, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/11/well/live/how-artificial-intelligence-could-transform-medicine.html.

Artificial intelligence (A.I.) is likely to change almost everything in medical practice, according to a new book called “Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again,” by Eric Topol, MD.

Dr. Topol told The Hospitalist that his book’s subtitle “is the paradox: the unexpected, far-reaching goal of A.I. that can, if used properly, restore the most important part of medicine – a deep patient-doctor relationship.”

That’s because A.I. can do more than enhance diagnoses; it can also help with tasks such as note-taking and reading scans, making it possible for hospitalists to spend more time connecting with their patients. “Hospitalists could have a much better handle on a patient’s dataset via algorithmic processing, providing alerts and augmented performance of hospitalists (when validated),” Dr. Topol said. “They can also expect far less keyboard use with the help of speech recognition, natural language processing, and deep learning.”In an interview with the New York Times, Dr. Topol said that by augmenting human performance, A.I. has the potential to markedly improve productivity, efficiency, work flow, accuracy and speed, both for doctors and for patients, giving more charge and control to consumers through algorithmic support of their data.

“We can’t, and will never, rely on only algorithms for interpretation of life and death matters,” he said. “That requires human expert contextualization, something machines can’t do.”Of course, there could be pitfalls. “The liabilities include breaches of privacy and security, hacking, the lack of explainability of most A.I. algorithms, the potential to worsen inequities, the embedded bias, and ethical quandaries,” he said.

Reference

1. O’Connor A. How Artificial Intelligence Could Transform Medicine. New York Times. March 11, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/11/well/live/how-artificial-intelligence-could-transform-medicine.html.

DAPA-HF: Dapagliflozin benefits regardless of age, HF severity

PHILADELPHIA – The substantial benefits from adding dapagliflozin to guideline-directed medical therapy for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction enrolled in the DAPA-HF trial applied to patients regardless of their age or baseline health status, a pair of new post hoc analyses suggest.

These findings emerged a day after a report that more fully delineated dapagliflozin’s consistent safety and efficacy in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) regardless of whether they also had type 2 diabetes. One of the new, post hoc analyses reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions suggested that even the most elderly enrolled patients, 75 years and older, had a similar cut in mortality and acute heart failure exacerbations, compared with younger patients. A second post hoc analysis indicated that patients with severe heart failure symptoms at entry into the trial received about as much benefit from the addition of dapagliflozin as did patients with mild baseline symptoms, measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ).

The primary results from the DAPA-HF (Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Heart Failure) trial, first reported in August 2019, showed that among more than 4,700 patients with HFrEF randomized to receive the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor dapagliflozin (Farxiga) on top of standard HFrEF medications or placebo, those who received dapagliflozin had a statistically significant, 26% decrease in their incidence of the primary study endpoint over a median 18 months, regardless of diabetes status (N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 21;381[21]:1995-2008).

“These benefits were entirely consistent across the range of ages studied,” extending from patients younger than 55 years to those older than 75 years, John McMurray, MD, said at the meeting. “In many parts of the world, particularly North America and Western Europe, we have an increasingly elderly population. Many patients with heart failure are much older than in clinical trials,” he said.