User login

COVID-19’s religious strain: Differentiating spirituality from pathology

As the world grapples with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the search for answers, comfort, how to cope, and how to make sense of it all has become paramount. People commonly turn to their faith in times of crisis, but this recent global public health emergency is unlike many have ever seen or could have imagined.1 What happens when the well-intentioned journey for spiritual insight intersects with psychiatric symptomatology? Where does the line between these phenomena get crossed? As a psychiatric resident and person who was raised in the Pentecostal faith, I have observed faith and psychopathology come to a head in the last 6 months. COVID-19 has dealt a religious strain of undocumented cases; I hope to shed light on the topic by sharing my experience of navigating the assessment and treatment plan of patients with psychiatric symptoms whose spiritual beliefs are a cornerstone of life.

Piety, or pathology?

The following approaches have helped me to identify what is driven by faith vs what is psychopathology:

While taking the patient history. Obtaining a history from a patient who professes to have strong spiritual beliefs and presents with psychiatric symptoms is similar to a standard patient interview, but pay special attention to how the patient came to the emergency department. Was there a family member, friend, or emergency medical services present at that time? During the interview, patients often appear “normal,” which may lead a clinician to question the reason for the consult, yet considering the recent events preceding the presentation will be a good place to start gathering the appropriate information for investigation.

Next, compare the patient’s recent daily functioning with his/her baseline. If this information comes solely from the patient, it may be skewed, so try to retrieve information from a collateral source. If the patient was accompanied by someone, request permission from the patient to speak with him/her. It may also be best in some instances to speak with the collateral source out of earshot of the patient. Be aware that collateral information that comes from just one source also could be biased, so search for additional contacts to help acquire a comprehensive representation of the circumstances.

Information about a patient could come from a faith leader because people often rely on their faith leaders when they are ill, in need of support, or in crisis.2 Faith leaders may have valuable information and insight into the patient and the history of the patient’s illness. In addition, diverse sources of collateral reports may be helpful because specific spiritual views and practices can vary even within one family or congregation. What may be an abnormal practice to some followers may be normal for others.3 When approaching these situations with parishioners, it is essential to maintain confidentiality.

While performing the clinical examination. As with any psychiatric diagnosis, other causative factors (metabolic and organic) need to be ruled out. Also, assess for the use of mood-altering substances. The patient may express offense or resistance to such questions, but maintain a matter-of-fact approach and explain that assessment for substance use is a routine part of the clinical examination. Approximately 18% of people in the United States with psychiatric disorders have a comorbid substance use disorder.4 However, keep in mind that a patient who refuses substance use screening is not necessarily hiding something. The road to being thorough may lead to strained rapport with the patient, and this risk must be balanced with providing the best care. As in any other clinical situation, seek evidence to both verify and clarify information without being deterred by a patient’s vocalization of spiritual tenants.

Learn about your patients’ beliefs

Do not feel defeated if you find these interviews difficult. Religion and symptomatology can overlap and fluctuate within the same faith group, which can make these types of assessments complex.5 In an effort to understand the patient more clearly, be sensitive to their spiritual practices and receptive to learning about unfamiliar spiritual beliefs. Be transparent about not knowing a specific belief or practice, and exhibit humility. Most patients are open to sharing their religious/spiritual views with a clinician who is sincere about wanting insight. Understanding the value of spiritual care is an important skill that many medical practitioners often lack.6 This understanding is especially critical when patients express worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic and how they are coping.

Continue to: Integrate your patient's spiritual requests

Integrate your patient’s spiritual requests

If you are comfortable with certain practices that do not compromise your values or beliefs or put a patient at risk, try to integrate your patients’ spiritual request(s) in their care. For a patient who serves a higher power, admitting to a problem (eg, fears related to COVID-19) or seeking professional help for symptoms (eg, anxiety, depression) may imply spiritual doubt. Patients may believe that seeking professional assistance means they are questioning the omnipotence of their deity to prevent or heal a condition. While spiritual distress can stimulate changes in behavior, it may not be pathological.

To avoid misdiagnosis, refer to the description “V62.89 (Z65.8) Religious or Spiritual Problem” in the DSM-5.7 If you find that it is a discord in faith that is affecting the patient’s presentation, and that this has not caused a psychiatric disorder, document this appropriately and provide the necessary resources to continue supporting the patient holistically.

1. Dein S, Loewenthal K, Lewis CA, et al. COVID-19, mental health and religion: an agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2020;23(1):1-9.

2. American Psychiatric Association Foundation. Mental health: a guide for faith leaders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Foundation; 2018.

3. Johnson CV, Friedman HL. Enlightened or delusional? Differentiating religious, spiritual, and transpersonal experiences from psychopathology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2008;48(4):505-527.

4. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of US adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1739-1747.

5. Menezes Jr A, Moreira-Almeida A. Differential diagnosis between spiritual experiences and mental disorders of religious content. Rev Psiq Clín. 2009;36(2):75-82.

6. Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Doctors discussing religion and spirituality: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(4):327-337.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:725.

As the world grapples with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the search for answers, comfort, how to cope, and how to make sense of it all has become paramount. People commonly turn to their faith in times of crisis, but this recent global public health emergency is unlike many have ever seen or could have imagined.1 What happens when the well-intentioned journey for spiritual insight intersects with psychiatric symptomatology? Where does the line between these phenomena get crossed? As a psychiatric resident and person who was raised in the Pentecostal faith, I have observed faith and psychopathology come to a head in the last 6 months. COVID-19 has dealt a religious strain of undocumented cases; I hope to shed light on the topic by sharing my experience of navigating the assessment and treatment plan of patients with psychiatric symptoms whose spiritual beliefs are a cornerstone of life.

Piety, or pathology?

The following approaches have helped me to identify what is driven by faith vs what is psychopathology:

While taking the patient history. Obtaining a history from a patient who professes to have strong spiritual beliefs and presents with psychiatric symptoms is similar to a standard patient interview, but pay special attention to how the patient came to the emergency department. Was there a family member, friend, or emergency medical services present at that time? During the interview, patients often appear “normal,” which may lead a clinician to question the reason for the consult, yet considering the recent events preceding the presentation will be a good place to start gathering the appropriate information for investigation.

Next, compare the patient’s recent daily functioning with his/her baseline. If this information comes solely from the patient, it may be skewed, so try to retrieve information from a collateral source. If the patient was accompanied by someone, request permission from the patient to speak with him/her. It may also be best in some instances to speak with the collateral source out of earshot of the patient. Be aware that collateral information that comes from just one source also could be biased, so search for additional contacts to help acquire a comprehensive representation of the circumstances.

Information about a patient could come from a faith leader because people often rely on their faith leaders when they are ill, in need of support, or in crisis.2 Faith leaders may have valuable information and insight into the patient and the history of the patient’s illness. In addition, diverse sources of collateral reports may be helpful because specific spiritual views and practices can vary even within one family or congregation. What may be an abnormal practice to some followers may be normal for others.3 When approaching these situations with parishioners, it is essential to maintain confidentiality.

While performing the clinical examination. As with any psychiatric diagnosis, other causative factors (metabolic and organic) need to be ruled out. Also, assess for the use of mood-altering substances. The patient may express offense or resistance to such questions, but maintain a matter-of-fact approach and explain that assessment for substance use is a routine part of the clinical examination. Approximately 18% of people in the United States with psychiatric disorders have a comorbid substance use disorder.4 However, keep in mind that a patient who refuses substance use screening is not necessarily hiding something. The road to being thorough may lead to strained rapport with the patient, and this risk must be balanced with providing the best care. As in any other clinical situation, seek evidence to both verify and clarify information without being deterred by a patient’s vocalization of spiritual tenants.

Learn about your patients’ beliefs

Do not feel defeated if you find these interviews difficult. Religion and symptomatology can overlap and fluctuate within the same faith group, which can make these types of assessments complex.5 In an effort to understand the patient more clearly, be sensitive to their spiritual practices and receptive to learning about unfamiliar spiritual beliefs. Be transparent about not knowing a specific belief or practice, and exhibit humility. Most patients are open to sharing their religious/spiritual views with a clinician who is sincere about wanting insight. Understanding the value of spiritual care is an important skill that many medical practitioners often lack.6 This understanding is especially critical when patients express worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic and how they are coping.

Continue to: Integrate your patient's spiritual requests

Integrate your patient’s spiritual requests

If you are comfortable with certain practices that do not compromise your values or beliefs or put a patient at risk, try to integrate your patients’ spiritual request(s) in their care. For a patient who serves a higher power, admitting to a problem (eg, fears related to COVID-19) or seeking professional help for symptoms (eg, anxiety, depression) may imply spiritual doubt. Patients may believe that seeking professional assistance means they are questioning the omnipotence of their deity to prevent or heal a condition. While spiritual distress can stimulate changes in behavior, it may not be pathological.

To avoid misdiagnosis, refer to the description “V62.89 (Z65.8) Religious or Spiritual Problem” in the DSM-5.7 If you find that it is a discord in faith that is affecting the patient’s presentation, and that this has not caused a psychiatric disorder, document this appropriately and provide the necessary resources to continue supporting the patient holistically.

As the world grapples with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the search for answers, comfort, how to cope, and how to make sense of it all has become paramount. People commonly turn to their faith in times of crisis, but this recent global public health emergency is unlike many have ever seen or could have imagined.1 What happens when the well-intentioned journey for spiritual insight intersects with psychiatric symptomatology? Where does the line between these phenomena get crossed? As a psychiatric resident and person who was raised in the Pentecostal faith, I have observed faith and psychopathology come to a head in the last 6 months. COVID-19 has dealt a religious strain of undocumented cases; I hope to shed light on the topic by sharing my experience of navigating the assessment and treatment plan of patients with psychiatric symptoms whose spiritual beliefs are a cornerstone of life.

Piety, or pathology?

The following approaches have helped me to identify what is driven by faith vs what is psychopathology:

While taking the patient history. Obtaining a history from a patient who professes to have strong spiritual beliefs and presents with psychiatric symptoms is similar to a standard patient interview, but pay special attention to how the patient came to the emergency department. Was there a family member, friend, or emergency medical services present at that time? During the interview, patients often appear “normal,” which may lead a clinician to question the reason for the consult, yet considering the recent events preceding the presentation will be a good place to start gathering the appropriate information for investigation.

Next, compare the patient’s recent daily functioning with his/her baseline. If this information comes solely from the patient, it may be skewed, so try to retrieve information from a collateral source. If the patient was accompanied by someone, request permission from the patient to speak with him/her. It may also be best in some instances to speak with the collateral source out of earshot of the patient. Be aware that collateral information that comes from just one source also could be biased, so search for additional contacts to help acquire a comprehensive representation of the circumstances.

Information about a patient could come from a faith leader because people often rely on their faith leaders when they are ill, in need of support, or in crisis.2 Faith leaders may have valuable information and insight into the patient and the history of the patient’s illness. In addition, diverse sources of collateral reports may be helpful because specific spiritual views and practices can vary even within one family or congregation. What may be an abnormal practice to some followers may be normal for others.3 When approaching these situations with parishioners, it is essential to maintain confidentiality.

While performing the clinical examination. As with any psychiatric diagnosis, other causative factors (metabolic and organic) need to be ruled out. Also, assess for the use of mood-altering substances. The patient may express offense or resistance to such questions, but maintain a matter-of-fact approach and explain that assessment for substance use is a routine part of the clinical examination. Approximately 18% of people in the United States with psychiatric disorders have a comorbid substance use disorder.4 However, keep in mind that a patient who refuses substance use screening is not necessarily hiding something. The road to being thorough may lead to strained rapport with the patient, and this risk must be balanced with providing the best care. As in any other clinical situation, seek evidence to both verify and clarify information without being deterred by a patient’s vocalization of spiritual tenants.

Learn about your patients’ beliefs

Do not feel defeated if you find these interviews difficult. Religion and symptomatology can overlap and fluctuate within the same faith group, which can make these types of assessments complex.5 In an effort to understand the patient more clearly, be sensitive to their spiritual practices and receptive to learning about unfamiliar spiritual beliefs. Be transparent about not knowing a specific belief or practice, and exhibit humility. Most patients are open to sharing their religious/spiritual views with a clinician who is sincere about wanting insight. Understanding the value of spiritual care is an important skill that many medical practitioners often lack.6 This understanding is especially critical when patients express worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic and how they are coping.

Continue to: Integrate your patient's spiritual requests

Integrate your patient’s spiritual requests

If you are comfortable with certain practices that do not compromise your values or beliefs or put a patient at risk, try to integrate your patients’ spiritual request(s) in their care. For a patient who serves a higher power, admitting to a problem (eg, fears related to COVID-19) or seeking professional help for symptoms (eg, anxiety, depression) may imply spiritual doubt. Patients may believe that seeking professional assistance means they are questioning the omnipotence of their deity to prevent or heal a condition. While spiritual distress can stimulate changes in behavior, it may not be pathological.

To avoid misdiagnosis, refer to the description “V62.89 (Z65.8) Religious or Spiritual Problem” in the DSM-5.7 If you find that it is a discord in faith that is affecting the patient’s presentation, and that this has not caused a psychiatric disorder, document this appropriately and provide the necessary resources to continue supporting the patient holistically.

1. Dein S, Loewenthal K, Lewis CA, et al. COVID-19, mental health and religion: an agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2020;23(1):1-9.

2. American Psychiatric Association Foundation. Mental health: a guide for faith leaders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Foundation; 2018.

3. Johnson CV, Friedman HL. Enlightened or delusional? Differentiating religious, spiritual, and transpersonal experiences from psychopathology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2008;48(4):505-527.

4. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of US adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1739-1747.

5. Menezes Jr A, Moreira-Almeida A. Differential diagnosis between spiritual experiences and mental disorders of religious content. Rev Psiq Clín. 2009;36(2):75-82.

6. Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Doctors discussing religion and spirituality: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(4):327-337.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:725.

1. Dein S, Loewenthal K, Lewis CA, et al. COVID-19, mental health and religion: an agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2020;23(1):1-9.

2. American Psychiatric Association Foundation. Mental health: a guide for faith leaders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Foundation; 2018.

3. Johnson CV, Friedman HL. Enlightened or delusional? Differentiating religious, spiritual, and transpersonal experiences from psychopathology. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2008;48(4):505-527.

4. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of US adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1739-1747.

5. Menezes Jr A, Moreira-Almeida A. Differential diagnosis between spiritual experiences and mental disorders of religious content. Rev Psiq Clín. 2009;36(2):75-82.

6. Best M, Butow P, Olver I. Doctors discussing religion and spirituality: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(4):327-337.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:725.

How much longer?

SHM has changed direction as needed during the pandemic

“How much longer?” As a kid, I can remember the long holiday car ride with my parents from my home in Annapolis, Md., to Upstate New York where my grandparents lived. At the time, the ride felt like an eternity: endless miles of frozen landscape, limited food, and a brother who constantly crossed over the invisible line that was my side of the car.

We made our parents crazy asking, “how much longer?” every few minutes. This was the late 1970s, with no GPS or Google Maps to give you arrival times to the minute, traffic warnings, or reroutes when the inevitable delays occurred. We just plowed ahead, and my parents’ answer was always something vague like, “in a few hours” or “we’re about halfway through.” They did not know when we’d arrive with certainty either.

We at SHM have that same feeling about the pandemic. How much longer? No one can tell us when the COVID-19 threat will abate. The experts’ answers are understandably vague, and the tools for forecasting are non-existent. Months? That is the best we know for now.

At SHM, we believe we will make it through this journey by adapting to roadblocks, providing tools for success to our professional community, and identifying opportunities for us to connect with each other, even if that means virtually.

Like the rest of the planet, the spring of 2020 hit SHM with a shock. Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego was shaping up to be the largest Annual Conference SHM ever had, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020 (PHM20) conference was well planned and expected to be a huge success, regional SHM chapters were meeting (and growing), and membership was thriving. I was transitioning out of my roles at Johns Hopkins and looking forward to my new role as CEO of SHM. All in all, March 2020 began with a fantastic outlook.

Wow, what a difference a few weeks made. We watched as the pandemic spread across regions of the country, concerned for the wellbeing of our patients and our hospitalists. We saw how our members were at the forefront of patient care during this crisis and understood that SHM had to adapt rapidly to meet their needs in real time.

By May, SHM had canceled HM20, Chapter activity was halted, PHM20 was on its way to being canceled, SHM committee work was put on hold, and I was spending my last few months at Hopkins as the chief medical officer at the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (which we got up and running in less than a month)! Whew.

But just like my dad could pivot our 1970s Chevy station wagon around a traffic jam in a flash, so too did SHM leadership start navigating around the COVID-19 landscape. As soon as HM20 was canceled, SHM immediately began planning for a virtual offering in August. We had hoped to attract at least 100 attendees and we were thrilled to have more than 1,000! PHM20 was switched from an in-person to a virtual meeting with 634 attendees. We launched numerous COVID-19 webinars and made our clinical and educational offerings open access. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19 and hospitalist-related topics – immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few. (And I even met with the POTUS & advocated for PPE.) The Journal of Hospital Medicine worked with authors to get important publications out at record speed. And of course, The Hospitalist connected all of us to our professional leaders and experts.

By the fall of 2020, SHM had actively adjusted to the “new normal” of this pandemic: SHM staff have settled into their new “work from home” environments, SHM Chapters are connecting members in the virtual world, SHM’s 2021 Annual Conference will be all virtual – rebranded as “SHM Converge” – and the State of Hospital Medicine Report (our every-other-year source for trends in hospital medicine) now has a COVID-19 supplement, which was developed at lightning speed. Even our SHM Board of Directors is meeting virtually! All this while advancing the routine work at SHM, which never faltered. Our work on resources for quality improvement, the opioid epidemic, wellbeing, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), leadership, professional development, advocacy, and so much more is as active as ever.

I don’t know how much longer we have on this very long pandemic journey, so I’ll use my father’s answer of “we’re about halfway through.” We have been immersed in it for months already, with months still ahead. But regardless of the upcoming twists and turns COVID-19 forces you, our patients, and our larger society to take, SHM is ready to change direction faster than a 1970s Chevy. The SHM staff, leadership, and members will be sure that hospitalists receive the tools to navigate these unprecedented times. Our patients need our skills to get through this as safely as possible. While we may not be able to tell them “how much longer,” we can certainly be prepared for the long road ahead as we begin 2021.

Dr. Howell is CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

SHM has changed direction as needed during the pandemic

SHM has changed direction as needed during the pandemic

“How much longer?” As a kid, I can remember the long holiday car ride with my parents from my home in Annapolis, Md., to Upstate New York where my grandparents lived. At the time, the ride felt like an eternity: endless miles of frozen landscape, limited food, and a brother who constantly crossed over the invisible line that was my side of the car.

We made our parents crazy asking, “how much longer?” every few minutes. This was the late 1970s, with no GPS or Google Maps to give you arrival times to the minute, traffic warnings, or reroutes when the inevitable delays occurred. We just plowed ahead, and my parents’ answer was always something vague like, “in a few hours” or “we’re about halfway through.” They did not know when we’d arrive with certainty either.

We at SHM have that same feeling about the pandemic. How much longer? No one can tell us when the COVID-19 threat will abate. The experts’ answers are understandably vague, and the tools for forecasting are non-existent. Months? That is the best we know for now.

At SHM, we believe we will make it through this journey by adapting to roadblocks, providing tools for success to our professional community, and identifying opportunities for us to connect with each other, even if that means virtually.

Like the rest of the planet, the spring of 2020 hit SHM with a shock. Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego was shaping up to be the largest Annual Conference SHM ever had, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020 (PHM20) conference was well planned and expected to be a huge success, regional SHM chapters were meeting (and growing), and membership was thriving. I was transitioning out of my roles at Johns Hopkins and looking forward to my new role as CEO of SHM. All in all, March 2020 began with a fantastic outlook.

Wow, what a difference a few weeks made. We watched as the pandemic spread across regions of the country, concerned for the wellbeing of our patients and our hospitalists. We saw how our members were at the forefront of patient care during this crisis and understood that SHM had to adapt rapidly to meet their needs in real time.

By May, SHM had canceled HM20, Chapter activity was halted, PHM20 was on its way to being canceled, SHM committee work was put on hold, and I was spending my last few months at Hopkins as the chief medical officer at the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (which we got up and running in less than a month)! Whew.

But just like my dad could pivot our 1970s Chevy station wagon around a traffic jam in a flash, so too did SHM leadership start navigating around the COVID-19 landscape. As soon as HM20 was canceled, SHM immediately began planning for a virtual offering in August. We had hoped to attract at least 100 attendees and we were thrilled to have more than 1,000! PHM20 was switched from an in-person to a virtual meeting with 634 attendees. We launched numerous COVID-19 webinars and made our clinical and educational offerings open access. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19 and hospitalist-related topics – immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few. (And I even met with the POTUS & advocated for PPE.) The Journal of Hospital Medicine worked with authors to get important publications out at record speed. And of course, The Hospitalist connected all of us to our professional leaders and experts.

By the fall of 2020, SHM had actively adjusted to the “new normal” of this pandemic: SHM staff have settled into their new “work from home” environments, SHM Chapters are connecting members in the virtual world, SHM’s 2021 Annual Conference will be all virtual – rebranded as “SHM Converge” – and the State of Hospital Medicine Report (our every-other-year source for trends in hospital medicine) now has a COVID-19 supplement, which was developed at lightning speed. Even our SHM Board of Directors is meeting virtually! All this while advancing the routine work at SHM, which never faltered. Our work on resources for quality improvement, the opioid epidemic, wellbeing, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), leadership, professional development, advocacy, and so much more is as active as ever.

I don’t know how much longer we have on this very long pandemic journey, so I’ll use my father’s answer of “we’re about halfway through.” We have been immersed in it for months already, with months still ahead. But regardless of the upcoming twists and turns COVID-19 forces you, our patients, and our larger society to take, SHM is ready to change direction faster than a 1970s Chevy. The SHM staff, leadership, and members will be sure that hospitalists receive the tools to navigate these unprecedented times. Our patients need our skills to get through this as safely as possible. While we may not be able to tell them “how much longer,” we can certainly be prepared for the long road ahead as we begin 2021.

Dr. Howell is CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“How much longer?” As a kid, I can remember the long holiday car ride with my parents from my home in Annapolis, Md., to Upstate New York where my grandparents lived. At the time, the ride felt like an eternity: endless miles of frozen landscape, limited food, and a brother who constantly crossed over the invisible line that was my side of the car.

We made our parents crazy asking, “how much longer?” every few minutes. This was the late 1970s, with no GPS or Google Maps to give you arrival times to the minute, traffic warnings, or reroutes when the inevitable delays occurred. We just plowed ahead, and my parents’ answer was always something vague like, “in a few hours” or “we’re about halfway through.” They did not know when we’d arrive with certainty either.

We at SHM have that same feeling about the pandemic. How much longer? No one can tell us when the COVID-19 threat will abate. The experts’ answers are understandably vague, and the tools for forecasting are non-existent. Months? That is the best we know for now.

At SHM, we believe we will make it through this journey by adapting to roadblocks, providing tools for success to our professional community, and identifying opportunities for us to connect with each other, even if that means virtually.

Like the rest of the planet, the spring of 2020 hit SHM with a shock. Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego was shaping up to be the largest Annual Conference SHM ever had, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020 (PHM20) conference was well planned and expected to be a huge success, regional SHM chapters were meeting (and growing), and membership was thriving. I was transitioning out of my roles at Johns Hopkins and looking forward to my new role as CEO of SHM. All in all, March 2020 began with a fantastic outlook.

Wow, what a difference a few weeks made. We watched as the pandemic spread across regions of the country, concerned for the wellbeing of our patients and our hospitalists. We saw how our members were at the forefront of patient care during this crisis and understood that SHM had to adapt rapidly to meet their needs in real time.

By May, SHM had canceled HM20, Chapter activity was halted, PHM20 was on its way to being canceled, SHM committee work was put on hold, and I was spending my last few months at Hopkins as the chief medical officer at the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (which we got up and running in less than a month)! Whew.

But just like my dad could pivot our 1970s Chevy station wagon around a traffic jam in a flash, so too did SHM leadership start navigating around the COVID-19 landscape. As soon as HM20 was canceled, SHM immediately began planning for a virtual offering in August. We had hoped to attract at least 100 attendees and we were thrilled to have more than 1,000! PHM20 was switched from an in-person to a virtual meeting with 634 attendees. We launched numerous COVID-19 webinars and made our clinical and educational offerings open access. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19 and hospitalist-related topics – immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few. (And I even met with the POTUS & advocated for PPE.) The Journal of Hospital Medicine worked with authors to get important publications out at record speed. And of course, The Hospitalist connected all of us to our professional leaders and experts.

By the fall of 2020, SHM had actively adjusted to the “new normal” of this pandemic: SHM staff have settled into their new “work from home” environments, SHM Chapters are connecting members in the virtual world, SHM’s 2021 Annual Conference will be all virtual – rebranded as “SHM Converge” – and the State of Hospital Medicine Report (our every-other-year source for trends in hospital medicine) now has a COVID-19 supplement, which was developed at lightning speed. Even our SHM Board of Directors is meeting virtually! All this while advancing the routine work at SHM, which never faltered. Our work on resources for quality improvement, the opioid epidemic, wellbeing, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), leadership, professional development, advocacy, and so much more is as active as ever.

I don’t know how much longer we have on this very long pandemic journey, so I’ll use my father’s answer of “we’re about halfway through.” We have been immersed in it for months already, with months still ahead. But regardless of the upcoming twists and turns COVID-19 forces you, our patients, and our larger society to take, SHM is ready to change direction faster than a 1970s Chevy. The SHM staff, leadership, and members will be sure that hospitalists receive the tools to navigate these unprecedented times. Our patients need our skills to get through this as safely as possible. While we may not be able to tell them “how much longer,” we can certainly be prepared for the long road ahead as we begin 2021.

Dr. Howell is CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Equitable Post-COVID-19 Care: A Practical Framework to Integrate Health Equity in Diabetes Management

From T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Dr. Ebekozien, Dr. Odugbesan, and Nicole Rioles); Barbara Davis Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO (Dr. Majidi); Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH (Dr. Jones); and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH (Dr. Kamboj)

Health equity has been described as the opportunity for all persons to obtain their highest level of health possible.1 Unfortunately, even with advances in technology and care practices, disparities persist in health care outcomes. Disparities in prevalence, prognosis, and outcomes still exist in diabetes management.2 Non-Hispanic Black and/or Hispanic populations are more likely to have worse glycemic control,3,4 to encounter more barriers in access to care,5 and to have higher levels of acute complications,4 and to use advanced technologies less frequently.4 Diabetes is one of the preexisting conditions that increase morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.6,7 Unfortunately, adverse outcomes from COVID-19 also disproportionately impact a specific vulnerable population.8,9 The urgent transition to managing diabetes remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate long-term inequities because some vulnerable patients might not have access to technology devices necessary for effective remote management.

Here, we describe how quality improvement (QI) tools and principles can be adapted into a framework for advancing health equity. Specifically, we describe a 10-step framework that may be applied in diabetes care management to achieve improvement, using a hypothetical example of increasing use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) among patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.10 This framework was developed to address the literature gap on practical ways health care providers can address inequities using QI principles, and was implemented by 1 of the authors at a local public health department.11 The framework’s iterative and comprehensive design makes it ideal for addressing inequities in chronic diseases like diabetes, which have multiple root causes with no easy solutions. The improvement program pilot received a national model practice award.11,12

10-Step Framework

Step 1: Review program/project baseline data for existing disparities. Diabetes programs and routine QI processes encourage existing data review to determine how effective the current system is working and if the existing process has a predictable pattern.13,14 Our equity-revised framework proposes a more in-depth review to stratify baseline data based on factors that might contribute to inequities, including race, age, income levels, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, insurance type, and zip code. This process will identify patients not served or unfairly impacted due to socioeconomic factors. For example, using the hypothetical example of improving CGM use, a team completes a preliminary data review and determines that baseline CGM use is 30% in the clinic population. However, in a review to assess for disparities, they also identify that patients on public insurance have a significantly lower CGM uptake of only 15%.

Step 2: Build an equitable project team, including patients with lived experiences. Routine projects typically have clinicians, administrative staff, and analytic staff as members of their team. In a post-COVID-19 world, every team needs to learn directly from people impacted and share decision-making power. The traditional approach to receiving feedback has generally been to collect responses using surveys or focus groups. We propose that individuals/families who are disproportionately impacted be included as active members on QI teams. For example, in the hypothetical example of the CGM project, team members would include patients with type 1 diabetes who are on public insurance and their families.

Step 3: Develop equity-focused goals. The traditional program involves the development of aims that are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound).15 The proposed framework encourages the inclusion of equity-revised goals (SMARTer) using insights from Steps 1 and 2. For example, your typical smart goal might be to increase the percentage of patients using CGM by 20% in 6 months, while a SMARTer goal would be to increase the proportion of patients using CGM by 20% and reduce the disparities among public and private insurance patients by 30% in 6 months.

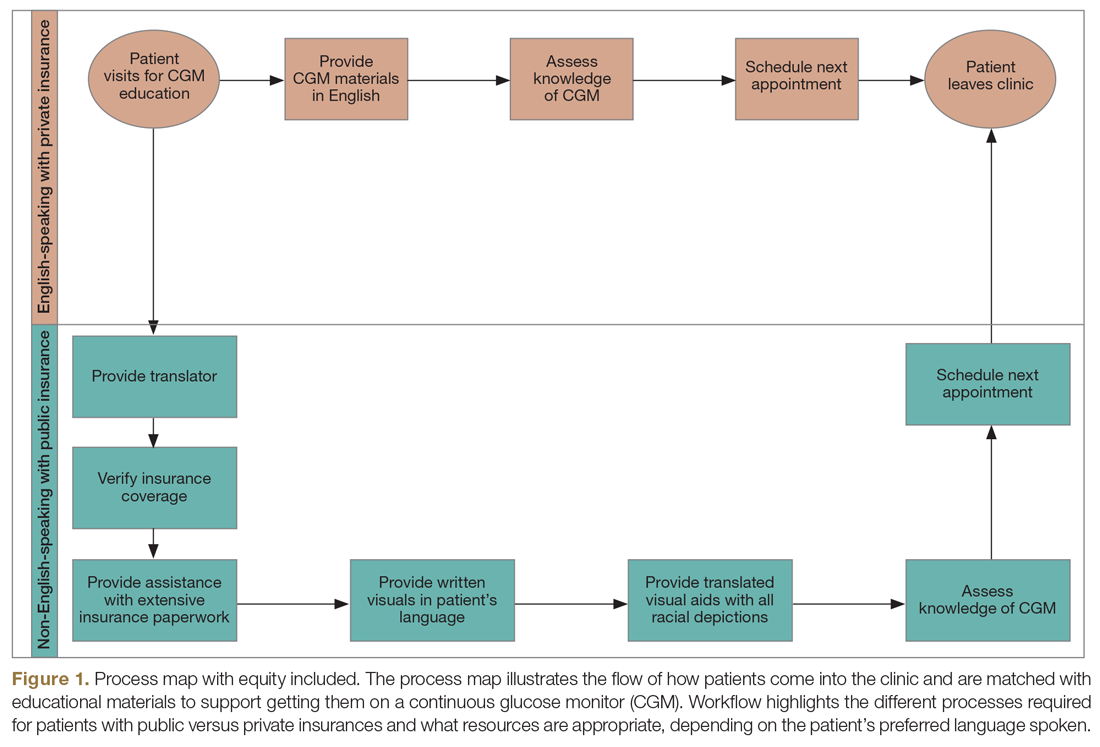

Step 4: Identify inequitable processes/pathways. Traditional QI programs might use a process map or flow diagram to depict the current state of a process visually.16 For example, in Figure 1, the process map diagram depicts some differences in the process for patients with public insurance as opposed to those with private insurance. The framework also advocates for using visual tools like process maps to depict how there might be inequitable pathways in a system. Visually identifying inequitable processes/pathways can help a team see barriers, address challenges, and pilot innovative solutions.

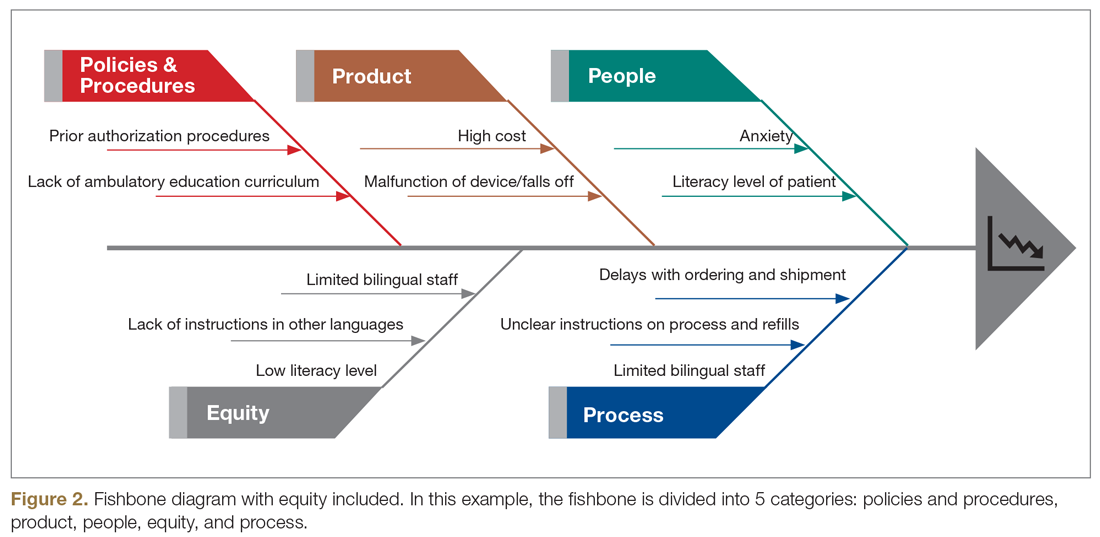

Step 5: Identify how socioeconomic factors are contributing to the current outcome. A good understanding of factors that contribute to the problem is an essential part of finding fundamental solutions. The fishbone diagram16 is a visualization tool used to identify contributing factors. When investigating contributing factors, it is commonplace to identify factors that fit into 1 of 5 categories: people, process, place, product, and policies (5 Ps). An equity-focused process will include equity as a new major factor category, and the socioeconomic impacts that contribute to inequities will be brainstormed and visually represented. For example, in the hypothetical CGM improvement example, an equity contributing factor is extensive CGM application paperwork for patients on public insurance as compared to those on private insurance. Figure 2 shows equity integrated into a fishbone diagram.

Step 6: Brainstorm possible improvements. Potential improvement ideas for the hypothetical CGM example might include redesigning the existing workflow, piloting CGM educational classes, and using a CGM barrier assessment tool to identify and address barriers to adoption.

Step 7: Use the decision matrix with equity as a criterion to prioritize improvement ideas. Decision matrix15 is a great tool that is frequently used to help teams prioritize potential ideas. Project team members must decide what criteria are important in prioritizing ideas to implement. Common criteria include implementation cost, time, and resources, but in addition to the common criteria, the team can specify ”impact on equity” as one of their criteria, alongside other standard criteria like impact.

Step 8: Test one small change at a time. This step is consistent with other traditional improvement models using the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model for improvement.17 During this phase, the team should make predictions on the expected impact of the intervention on outcomes. For example, in the hypothetical example, the team predicts that testing and expanding CGM classes will reduce disparities among public versus private health insurance users by 5% and increase overall CGM uptake by 10%.

Step 9: Measure and compare results with predictions to identify inequitable practices or consequences. After each test of change, the team should review the results, including implementation cost considerations, and compare them to the predictions in the earlier step. The team should also document the potential reasons why their predictions were correct or inaccurate, and whether there were any unforeseen outcomes from the intervention.

Step 10: Celebrate small wins and repeat the process. Making fundamental and equitable changes takes time. This framework aimed at undoing inequities, particularly those inequities that have been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, is iterative and ongoing.18,19 Not every test of change will impact the outcome or reduce inequity, but over time, each change will impact the next, generating sustainable effects.

Conclusion

There are ongoing studies examining the adverse outcomes and potential health inequities for patients with diabetes impacted by COVID-19.20 Health care providers need to plan for post-COVID-19 care, keeping in mind that the pandemic might worsen already existing health disparities in diabetes management.3,4,21 This work will involve an intentional approach to address structural and systemic racism.22 Therefore, the work of building health equity solutions must be rooted in racial justice, economic equity, and equitable access to health care and education.

Initiatives like this are currently being funded through foundation grants as well as state and federal research or program grants. Regional and national payors, including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, are currently piloting long-term sustainable funding models through programs like accountable care organizations and the Accountable Health Communities Model.23

Health systems can successfully address health equity and racial justice, using a framework as described above, to identify determinants of health, develop policies to expand access to care for the most vulnerable patients, distribute decision-making power, and train staff by naming structural racism as a driver of health inequities.

Acknowledgment: The authors acknowledge the contributions of patients, families, diabetes care teams, and collaborators within the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative, who continually seek to improve care and outcomes for people living with diabetes.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, 11 Avenue De La Fayette, Boston, MA 02115; oebekozien@t1dexchange.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: T1D Exchange QI Collaborative is funded by The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. No specific funding was received for this manuscript or the development of this framework.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes; quality improvement; QI framework; racial justice; health disparities.

1. American Public Health Association Health Equity web site. https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-equity. Accessed June 4, 2020.

2. Lado J, Lipman T. Racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of youth with type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45:453-461.

3. Kahkoska AR, Shay CM, Crandell J, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with glycemic control and hemoglobin A1c levels in youth with type 1 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e181851.

4. Willi SM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al; T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Racial-ethnic disparities in management and outcomes among children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2015;135:424-434.

5. Valenzuela JM, Seid M, Waitzfelder B, et al. Prevalence of and disparities in barriers to care experienced by youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1369-1375.

6. Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: Knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142.

7. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle Region - case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012-2022.

8. Laurencin CT, McClinton A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7:398-402.

9. Shah M, Sachdeva M, Dodiuk-Gad RP. COVID-19 and racial disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e35.

10. Ebekozien O, Rioles N, DeSalvo D, et al. Improving continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) use across national centers: results from the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI). Diabetes. 2020;69(Supplement 1):145-LB.

11. Ebekozien O. QI methodology to address health equity. Presented at American Society of Quality BOSCON 2018; Boston, MA; March 19 and 20, 2018.

12. 2019 Model Practice Award, Building A Culture of Improvement. National Association of County and City Health Officials web site. www.naccho.org/membership/awards/model-practices. Accessed June 4, 2020.

13. Nuckols TK, Keeler E, Anderson LJ, et al. Economic evaluation of quality improvement interventions designed to improve glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and weighted regression analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:985‐993.

14. Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Arcangeli A, et al. Baseline quality-of-care data from a quality-improvement program implemented by a network of diabetes outpatient clinics. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2166‐2168.

15. McQuillan RF, Silver SA, Harel Z, et al. How to measure and interpret quality improvement data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:908-914.

16. Siddiqi FS. Quality improvement in diabetes care: time for us to step up? Can J Diabetes. 2019;43:233.

17. Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:290‐298.

18. Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. African American COVID-19 mortality: a sentinel event. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2746-2748..

19. Muniyappa R, Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318:E736-E741.

20. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e83-e85.

21. Majidi S, Ebekozien O, Noor N, et al. Inequities in health outcomes among patients in the T1D Exchange-QI Collaborative. Diabetes. 2020;69(Supplement 1):1220-P. https://doi.org/10.2337/ db20-1220.-P.

22. Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32:20-47.

23. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accountable Health Communities Model. CMS.gov web site. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm. Accessed October 10, 2020.

From T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Dr. Ebekozien, Dr. Odugbesan, and Nicole Rioles); Barbara Davis Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO (Dr. Majidi); Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH (Dr. Jones); and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH (Dr. Kamboj)

Health equity has been described as the opportunity for all persons to obtain their highest level of health possible.1 Unfortunately, even with advances in technology and care practices, disparities persist in health care outcomes. Disparities in prevalence, prognosis, and outcomes still exist in diabetes management.2 Non-Hispanic Black and/or Hispanic populations are more likely to have worse glycemic control,3,4 to encounter more barriers in access to care,5 and to have higher levels of acute complications,4 and to use advanced technologies less frequently.4 Diabetes is one of the preexisting conditions that increase morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.6,7 Unfortunately, adverse outcomes from COVID-19 also disproportionately impact a specific vulnerable population.8,9 The urgent transition to managing diabetes remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate long-term inequities because some vulnerable patients might not have access to technology devices necessary for effective remote management.

Here, we describe how quality improvement (QI) tools and principles can be adapted into a framework for advancing health equity. Specifically, we describe a 10-step framework that may be applied in diabetes care management to achieve improvement, using a hypothetical example of increasing use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) among patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.10 This framework was developed to address the literature gap on practical ways health care providers can address inequities using QI principles, and was implemented by 1 of the authors at a local public health department.11 The framework’s iterative and comprehensive design makes it ideal for addressing inequities in chronic diseases like diabetes, which have multiple root causes with no easy solutions. The improvement program pilot received a national model practice award.11,12

10-Step Framework

Step 1: Review program/project baseline data for existing disparities. Diabetes programs and routine QI processes encourage existing data review to determine how effective the current system is working and if the existing process has a predictable pattern.13,14 Our equity-revised framework proposes a more in-depth review to stratify baseline data based on factors that might contribute to inequities, including race, age, income levels, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, insurance type, and zip code. This process will identify patients not served or unfairly impacted due to socioeconomic factors. For example, using the hypothetical example of improving CGM use, a team completes a preliminary data review and determines that baseline CGM use is 30% in the clinic population. However, in a review to assess for disparities, they also identify that patients on public insurance have a significantly lower CGM uptake of only 15%.

Step 2: Build an equitable project team, including patients with lived experiences. Routine projects typically have clinicians, administrative staff, and analytic staff as members of their team. In a post-COVID-19 world, every team needs to learn directly from people impacted and share decision-making power. The traditional approach to receiving feedback has generally been to collect responses using surveys or focus groups. We propose that individuals/families who are disproportionately impacted be included as active members on QI teams. For example, in the hypothetical example of the CGM project, team members would include patients with type 1 diabetes who are on public insurance and their families.

Step 3: Develop equity-focused goals. The traditional program involves the development of aims that are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound).15 The proposed framework encourages the inclusion of equity-revised goals (SMARTer) using insights from Steps 1 and 2. For example, your typical smart goal might be to increase the percentage of patients using CGM by 20% in 6 months, while a SMARTer goal would be to increase the proportion of patients using CGM by 20% and reduce the disparities among public and private insurance patients by 30% in 6 months.

Step 4: Identify inequitable processes/pathways. Traditional QI programs might use a process map or flow diagram to depict the current state of a process visually.16 For example, in Figure 1, the process map diagram depicts some differences in the process for patients with public insurance as opposed to those with private insurance. The framework also advocates for using visual tools like process maps to depict how there might be inequitable pathways in a system. Visually identifying inequitable processes/pathways can help a team see barriers, address challenges, and pilot innovative solutions.

Step 5: Identify how socioeconomic factors are contributing to the current outcome. A good understanding of factors that contribute to the problem is an essential part of finding fundamental solutions. The fishbone diagram16 is a visualization tool used to identify contributing factors. When investigating contributing factors, it is commonplace to identify factors that fit into 1 of 5 categories: people, process, place, product, and policies (5 Ps). An equity-focused process will include equity as a new major factor category, and the socioeconomic impacts that contribute to inequities will be brainstormed and visually represented. For example, in the hypothetical CGM improvement example, an equity contributing factor is extensive CGM application paperwork for patients on public insurance as compared to those on private insurance. Figure 2 shows equity integrated into a fishbone diagram.

Step 6: Brainstorm possible improvements. Potential improvement ideas for the hypothetical CGM example might include redesigning the existing workflow, piloting CGM educational classes, and using a CGM barrier assessment tool to identify and address barriers to adoption.

Step 7: Use the decision matrix with equity as a criterion to prioritize improvement ideas. Decision matrix15 is a great tool that is frequently used to help teams prioritize potential ideas. Project team members must decide what criteria are important in prioritizing ideas to implement. Common criteria include implementation cost, time, and resources, but in addition to the common criteria, the team can specify ”impact on equity” as one of their criteria, alongside other standard criteria like impact.

Step 8: Test one small change at a time. This step is consistent with other traditional improvement models using the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model for improvement.17 During this phase, the team should make predictions on the expected impact of the intervention on outcomes. For example, in the hypothetical example, the team predicts that testing and expanding CGM classes will reduce disparities among public versus private health insurance users by 5% and increase overall CGM uptake by 10%.

Step 9: Measure and compare results with predictions to identify inequitable practices or consequences. After each test of change, the team should review the results, including implementation cost considerations, and compare them to the predictions in the earlier step. The team should also document the potential reasons why their predictions were correct or inaccurate, and whether there were any unforeseen outcomes from the intervention.

Step 10: Celebrate small wins and repeat the process. Making fundamental and equitable changes takes time. This framework aimed at undoing inequities, particularly those inequities that have been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, is iterative and ongoing.18,19 Not every test of change will impact the outcome or reduce inequity, but over time, each change will impact the next, generating sustainable effects.

Conclusion

There are ongoing studies examining the adverse outcomes and potential health inequities for patients with diabetes impacted by COVID-19.20 Health care providers need to plan for post-COVID-19 care, keeping in mind that the pandemic might worsen already existing health disparities in diabetes management.3,4,21 This work will involve an intentional approach to address structural and systemic racism.22 Therefore, the work of building health equity solutions must be rooted in racial justice, economic equity, and equitable access to health care and education.

Initiatives like this are currently being funded through foundation grants as well as state and federal research or program grants. Regional and national payors, including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, are currently piloting long-term sustainable funding models through programs like accountable care organizations and the Accountable Health Communities Model.23

Health systems can successfully address health equity and racial justice, using a framework as described above, to identify determinants of health, develop policies to expand access to care for the most vulnerable patients, distribute decision-making power, and train staff by naming structural racism as a driver of health inequities.

Acknowledgment: The authors acknowledge the contributions of patients, families, diabetes care teams, and collaborators within the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative, who continually seek to improve care and outcomes for people living with diabetes.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, 11 Avenue De La Fayette, Boston, MA 02115; oebekozien@t1dexchange.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: T1D Exchange QI Collaborative is funded by The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. No specific funding was received for this manuscript or the development of this framework.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes; quality improvement; QI framework; racial justice; health disparities.

From T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Dr. Ebekozien, Dr. Odugbesan, and Nicole Rioles); Barbara Davis Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO (Dr. Majidi); Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH (Dr. Jones); and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH (Dr. Kamboj)

Health equity has been described as the opportunity for all persons to obtain their highest level of health possible.1 Unfortunately, even with advances in technology and care practices, disparities persist in health care outcomes. Disparities in prevalence, prognosis, and outcomes still exist in diabetes management.2 Non-Hispanic Black and/or Hispanic populations are more likely to have worse glycemic control,3,4 to encounter more barriers in access to care,5 and to have higher levels of acute complications,4 and to use advanced technologies less frequently.4 Diabetes is one of the preexisting conditions that increase morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.6,7 Unfortunately, adverse outcomes from COVID-19 also disproportionately impact a specific vulnerable population.8,9 The urgent transition to managing diabetes remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate long-term inequities because some vulnerable patients might not have access to technology devices necessary for effective remote management.

Here, we describe how quality improvement (QI) tools and principles can be adapted into a framework for advancing health equity. Specifically, we describe a 10-step framework that may be applied in diabetes care management to achieve improvement, using a hypothetical example of increasing use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) among patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.10 This framework was developed to address the literature gap on practical ways health care providers can address inequities using QI principles, and was implemented by 1 of the authors at a local public health department.11 The framework’s iterative and comprehensive design makes it ideal for addressing inequities in chronic diseases like diabetes, which have multiple root causes with no easy solutions. The improvement program pilot received a national model practice award.11,12

10-Step Framework

Step 1: Review program/project baseline data for existing disparities. Diabetes programs and routine QI processes encourage existing data review to determine how effective the current system is working and if the existing process has a predictable pattern.13,14 Our equity-revised framework proposes a more in-depth review to stratify baseline data based on factors that might contribute to inequities, including race, age, income levels, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, insurance type, and zip code. This process will identify patients not served or unfairly impacted due to socioeconomic factors. For example, using the hypothetical example of improving CGM use, a team completes a preliminary data review and determines that baseline CGM use is 30% in the clinic population. However, in a review to assess for disparities, they also identify that patients on public insurance have a significantly lower CGM uptake of only 15%.

Step 2: Build an equitable project team, including patients with lived experiences. Routine projects typically have clinicians, administrative staff, and analytic staff as members of their team. In a post-COVID-19 world, every team needs to learn directly from people impacted and share decision-making power. The traditional approach to receiving feedback has generally been to collect responses using surveys or focus groups. We propose that individuals/families who are disproportionately impacted be included as active members on QI teams. For example, in the hypothetical example of the CGM project, team members would include patients with type 1 diabetes who are on public insurance and their families.

Step 3: Develop equity-focused goals. The traditional program involves the development of aims that are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound).15 The proposed framework encourages the inclusion of equity-revised goals (SMARTer) using insights from Steps 1 and 2. For example, your typical smart goal might be to increase the percentage of patients using CGM by 20% in 6 months, while a SMARTer goal would be to increase the proportion of patients using CGM by 20% and reduce the disparities among public and private insurance patients by 30% in 6 months.

Step 4: Identify inequitable processes/pathways. Traditional QI programs might use a process map or flow diagram to depict the current state of a process visually.16 For example, in Figure 1, the process map diagram depicts some differences in the process for patients with public insurance as opposed to those with private insurance. The framework also advocates for using visual tools like process maps to depict how there might be inequitable pathways in a system. Visually identifying inequitable processes/pathways can help a team see barriers, address challenges, and pilot innovative solutions.

Step 5: Identify how socioeconomic factors are contributing to the current outcome. A good understanding of factors that contribute to the problem is an essential part of finding fundamental solutions. The fishbone diagram16 is a visualization tool used to identify contributing factors. When investigating contributing factors, it is commonplace to identify factors that fit into 1 of 5 categories: people, process, place, product, and policies (5 Ps). An equity-focused process will include equity as a new major factor category, and the socioeconomic impacts that contribute to inequities will be brainstormed and visually represented. For example, in the hypothetical CGM improvement example, an equity contributing factor is extensive CGM application paperwork for patients on public insurance as compared to those on private insurance. Figure 2 shows equity integrated into a fishbone diagram.

Step 6: Brainstorm possible improvements. Potential improvement ideas for the hypothetical CGM example might include redesigning the existing workflow, piloting CGM educational classes, and using a CGM barrier assessment tool to identify and address barriers to adoption.

Step 7: Use the decision matrix with equity as a criterion to prioritize improvement ideas. Decision matrix15 is a great tool that is frequently used to help teams prioritize potential ideas. Project team members must decide what criteria are important in prioritizing ideas to implement. Common criteria include implementation cost, time, and resources, but in addition to the common criteria, the team can specify ”impact on equity” as one of their criteria, alongside other standard criteria like impact.

Step 8: Test one small change at a time. This step is consistent with other traditional improvement models using the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) model for improvement.17 During this phase, the team should make predictions on the expected impact of the intervention on outcomes. For example, in the hypothetical example, the team predicts that testing and expanding CGM classes will reduce disparities among public versus private health insurance users by 5% and increase overall CGM uptake by 10%.

Step 9: Measure and compare results with predictions to identify inequitable practices or consequences. After each test of change, the team should review the results, including implementation cost considerations, and compare them to the predictions in the earlier step. The team should also document the potential reasons why their predictions were correct or inaccurate, and whether there were any unforeseen outcomes from the intervention.

Step 10: Celebrate small wins and repeat the process. Making fundamental and equitable changes takes time. This framework aimed at undoing inequities, particularly those inequities that have been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, is iterative and ongoing.18,19 Not every test of change will impact the outcome or reduce inequity, but over time, each change will impact the next, generating sustainable effects.

Conclusion

There are ongoing studies examining the adverse outcomes and potential health inequities for patients with diabetes impacted by COVID-19.20 Health care providers need to plan for post-COVID-19 care, keeping in mind that the pandemic might worsen already existing health disparities in diabetes management.3,4,21 This work will involve an intentional approach to address structural and systemic racism.22 Therefore, the work of building health equity solutions must be rooted in racial justice, economic equity, and equitable access to health care and education.

Initiatives like this are currently being funded through foundation grants as well as state and federal research or program grants. Regional and national payors, including the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, are currently piloting long-term sustainable funding models through programs like accountable care organizations and the Accountable Health Communities Model.23

Health systems can successfully address health equity and racial justice, using a framework as described above, to identify determinants of health, develop policies to expand access to care for the most vulnerable patients, distribute decision-making power, and train staff by naming structural racism as a driver of health inequities.

Acknowledgment: The authors acknowledge the contributions of patients, families, diabetes care teams, and collaborators within the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative, who continually seek to improve care and outcomes for people living with diabetes.

Corresponding author: Osagie Ebekozien, MD, 11 Avenue De La Fayette, Boston, MA 02115; oebekozien@t1dexchange.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding: T1D Exchange QI Collaborative is funded by The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. No specific funding was received for this manuscript or the development of this framework.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes; quality improvement; QI framework; racial justice; health disparities.

1. American Public Health Association Health Equity web site. https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-equity. Accessed June 4, 2020.

2. Lado J, Lipman T. Racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of youth with type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45:453-461.

3. Kahkoska AR, Shay CM, Crandell J, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with glycemic control and hemoglobin A1c levels in youth with type 1 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e181851.

4. Willi SM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al; T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Racial-ethnic disparities in management and outcomes among children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2015;135:424-434.

5. Valenzuela JM, Seid M, Waitzfelder B, et al. Prevalence of and disparities in barriers to care experienced by youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1369-1375.

6. Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: Knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142.

7. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle Region - case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012-2022.

8. Laurencin CT, McClinton A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7:398-402.

9. Shah M, Sachdeva M, Dodiuk-Gad RP. COVID-19 and racial disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e35.

10. Ebekozien O, Rioles N, DeSalvo D, et al. Improving continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) use across national centers: results from the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI). Diabetes. 2020;69(Supplement 1):145-LB.

11. Ebekozien O. QI methodology to address health equity. Presented at American Society of Quality BOSCON 2018; Boston, MA; March 19 and 20, 2018.

12. 2019 Model Practice Award, Building A Culture of Improvement. National Association of County and City Health Officials web site. www.naccho.org/membership/awards/model-practices. Accessed June 4, 2020.

13. Nuckols TK, Keeler E, Anderson LJ, et al. Economic evaluation of quality improvement interventions designed to improve glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and weighted regression analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:985‐993.

14. Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Arcangeli A, et al. Baseline quality-of-care data from a quality-improvement program implemented by a network of diabetes outpatient clinics. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2166‐2168.

15. McQuillan RF, Silver SA, Harel Z, et al. How to measure and interpret quality improvement data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:908-914.

16. Siddiqi FS. Quality improvement in diabetes care: time for us to step up? Can J Diabetes. 2019;43:233.

17. Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:290‐298.

18. Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. African American COVID-19 mortality: a sentinel event. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2746-2748..

19. Muniyappa R, Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318:E736-E741.

20. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e83-e85.

21. Majidi S, Ebekozien O, Noor N, et al. Inequities in health outcomes among patients in the T1D Exchange-QI Collaborative. Diabetes. 2020;69(Supplement 1):1220-P. https://doi.org/10.2337/ db20-1220.-P.

22. Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32:20-47.

23. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accountable Health Communities Model. CMS.gov web site. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm. Accessed October 10, 2020.

1. American Public Health Association Health Equity web site. https://www.apha.org/topics-and-issues/health-equity. Accessed June 4, 2020.

2. Lado J, Lipman T. Racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of youth with type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2016;45:453-461.

3. Kahkoska AR, Shay CM, Crandell J, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with glycemic control and hemoglobin A1c levels in youth with type 1 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e181851.

4. Willi SM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al; T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Racial-ethnic disparities in management and outcomes among children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2015;135:424-434.

5. Valenzuela JM, Seid M, Waitzfelder B, et al. Prevalence of and disparities in barriers to care experienced by youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1369-1375.

6. Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: Knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142.

7. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle Region - case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012-2022.

8. Laurencin CT, McClinton A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a call to action to identify and address racial and ethnic disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7:398-402.

9. Shah M, Sachdeva M, Dodiuk-Gad RP. COVID-19 and racial disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e35.

10. Ebekozien O, Rioles N, DeSalvo D, et al. Improving continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) use across national centers: results from the T1D Exchange Quality Improvement Collaborative (T1DX-QI). Diabetes. 2020;69(Supplement 1):145-LB.

11. Ebekozien O. QI methodology to address health equity. Presented at American Society of Quality BOSCON 2018; Boston, MA; March 19 and 20, 2018.

12. 2019 Model Practice Award, Building A Culture of Improvement. National Association of County and City Health Officials web site. www.naccho.org/membership/awards/model-practices. Accessed June 4, 2020.

13. Nuckols TK, Keeler E, Anderson LJ, et al. Economic evaluation of quality improvement interventions designed to improve glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and weighted regression analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:985‐993.

14. Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Arcangeli A, et al. Baseline quality-of-care data from a quality-improvement program implemented by a network of diabetes outpatient clinics. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2166‐2168.

15. McQuillan RF, Silver SA, Harel Z, et al. How to measure and interpret quality improvement data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:908-914.

16. Siddiqi FS. Quality improvement in diabetes care: time for us to step up? Can J Diabetes. 2019;43:233.

17. Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:290‐298.

18. Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. African American COVID-19 mortality: a sentinel event. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2746-2748..

19. Muniyappa R, Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, coronaviruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318:E736-E741.

20. Ebekozien OA, Noor N, Gallagher MP, Alonso GT. Type 1 diabetes and COVID-19: preliminary findings from a multicenter surveillance study in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:e83-e85.

21. Majidi S, Ebekozien O, Noor N, et al. Inequities in health outcomes among patients in the T1D Exchange-QI Collaborative. Diabetes. 2020;69(Supplement 1):1220-P. https://doi.org/10.2337/ db20-1220.-P.

22. Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32:20-47.

23. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accountable Health Communities Model. CMS.gov web site. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/ahcm. Accessed October 10, 2020.

Tips for physicians, patients to make the most of the holidays amid COVID

“We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope,” Martin Luther King, Jr.

This holiday season will be like no other. We will remember it for the rest of our lives, and we will look back to see how we faced the holidays during a pandemic.

Like the rest of 2020, the holidays will need to be reimagined. Years and even decades of tradition will be broken as we place health above merriment.

Here are a few tips to help all of us and our patients make the most of this holiday season.

- Reprioritize: This holiday season will be about depth not breadth, quality not quantity, and less not more. Trips are canceled and gatherings have shrunk. We are not running from store to store or party to party. Instead, you will find yourself surrounded by fewer friends and family. Some will be alone to optimally protect their health and the health of others. Do your best to focus on the half-full portion.