User login

Colonic Crohn’s: Segmental vs. total colectomy

Segmental rather than total colectomy may be a safe and effective choice for some patients with colonic Crohn’s disease (cCD), showing significantly lower rates of repeat surgery and reduced need for stoma, according to long-term data.

Gianluca Pellino, MD, with the department of advanced medical and surgical sciences, Università degli Studi della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” in Naples, Italy, led the study, which was published in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis.

CD of the colon has gotten less attention than the more prevalent small bowel disease, according to the authors, but it can be debilitating and permanently reduce quality of life. Isolated cCD incidence ranges between 14% and 32% of all CD cases from the start of disease. Historically, extensive resection has been linked with longer disease-free intervals, and reduced repeat surgeries compared with segmental resections. However, most of the data have included low-quality evidence and reports typically have not adequately considered the role of biologics or advances in perioperative management of patients with cCD, the authors wrote.

The Segmental Colectomy for Crohn’s disease (SCOTCH) international study included a retrospective analysis of data from six European Inflammatory Bowel Disease referral centers on patients operated on between 2000 and 2019 who had either segmental or total colectomy for cCD.

Among 687 patients (301 male; 386 female), segmental colectomy was performed in 285 (41.5%) of cases and total colectomy in 402 (58.5%). The 15-year surgical recurrence rate was 44% among patients who had TC and 27% for patients with segmental colectomy (P = .006).

The SCOTCH study found that segmental colectomy may be performed safely and effectively and reduce the need for stoma in cCD patients without increasing risk of repeat surgeries compared with total colectomy, which was the primary measure investigators studied.

The findings of this study also suggest that biologics, when used early and correctly, may allow more conservative options for cCD, with a fivefold reduction in surgical recurrence risk in patients who have one to three large bowel locations.

Morbidity and mortality were similar in the SC and TC groups.

Among the limitations of the study are that the total colectomy patients in the study had indications for total colectomy that were also higher risk factors for recurrence – for instance, perianal disease.

The authors wrote, “The differences between patients who underwent SC vs TC might have accounted for the choice of one treatment over the other. It is however difficult to obtain a homogenous population of cCD patients.” They also cite the difficulties in gathering enough patients for randomized trials.

“These findings need to be discussed with the patients, and the choice of operation should be individualised,” they concluded. “Multidisciplinary management of patients with cCD is of critical importance to achieve optimal long-term results of bowel-sparing approaches.”

Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic, who was not part of the study, told this publication the findings should be considered confirmatory rather than suggestive of practice change.

“If a patient has a limited segment of Crohn’s, for example ileocecal Crohn’s – a common phenotype – then the standard of care is a segmental resection and primary anastomosis,” he said. “If the patient has more extensive CD – perianal fistula, colonic-only CD – they’re more likely to undergo a total colectomy. This study confirms that.“

The authors and Dr. Regueiro declared no relevant financial relationships.

Segmental rather than total colectomy may be a safe and effective choice for some patients with colonic Crohn’s disease (cCD), showing significantly lower rates of repeat surgery and reduced need for stoma, according to long-term data.

Gianluca Pellino, MD, with the department of advanced medical and surgical sciences, Università degli Studi della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” in Naples, Italy, led the study, which was published in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis.

CD of the colon has gotten less attention than the more prevalent small bowel disease, according to the authors, but it can be debilitating and permanently reduce quality of life. Isolated cCD incidence ranges between 14% and 32% of all CD cases from the start of disease. Historically, extensive resection has been linked with longer disease-free intervals, and reduced repeat surgeries compared with segmental resections. However, most of the data have included low-quality evidence and reports typically have not adequately considered the role of biologics or advances in perioperative management of patients with cCD, the authors wrote.

The Segmental Colectomy for Crohn’s disease (SCOTCH) international study included a retrospective analysis of data from six European Inflammatory Bowel Disease referral centers on patients operated on between 2000 and 2019 who had either segmental or total colectomy for cCD.

Among 687 patients (301 male; 386 female), segmental colectomy was performed in 285 (41.5%) of cases and total colectomy in 402 (58.5%). The 15-year surgical recurrence rate was 44% among patients who had TC and 27% for patients with segmental colectomy (P = .006).

The SCOTCH study found that segmental colectomy may be performed safely and effectively and reduce the need for stoma in cCD patients without increasing risk of repeat surgeries compared with total colectomy, which was the primary measure investigators studied.

The findings of this study also suggest that biologics, when used early and correctly, may allow more conservative options for cCD, with a fivefold reduction in surgical recurrence risk in patients who have one to three large bowel locations.

Morbidity and mortality were similar in the SC and TC groups.

Among the limitations of the study are that the total colectomy patients in the study had indications for total colectomy that were also higher risk factors for recurrence – for instance, perianal disease.

The authors wrote, “The differences between patients who underwent SC vs TC might have accounted for the choice of one treatment over the other. It is however difficult to obtain a homogenous population of cCD patients.” They also cite the difficulties in gathering enough patients for randomized trials.

“These findings need to be discussed with the patients, and the choice of operation should be individualised,” they concluded. “Multidisciplinary management of patients with cCD is of critical importance to achieve optimal long-term results of bowel-sparing approaches.”

Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic, who was not part of the study, told this publication the findings should be considered confirmatory rather than suggestive of practice change.

“If a patient has a limited segment of Crohn’s, for example ileocecal Crohn’s – a common phenotype – then the standard of care is a segmental resection and primary anastomosis,” he said. “If the patient has more extensive CD – perianal fistula, colonic-only CD – they’re more likely to undergo a total colectomy. This study confirms that.“

The authors and Dr. Regueiro declared no relevant financial relationships.

Segmental rather than total colectomy may be a safe and effective choice for some patients with colonic Crohn’s disease (cCD), showing significantly lower rates of repeat surgery and reduced need for stoma, according to long-term data.

Gianluca Pellino, MD, with the department of advanced medical and surgical sciences, Università degli Studi della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” in Naples, Italy, led the study, which was published in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis.

CD of the colon has gotten less attention than the more prevalent small bowel disease, according to the authors, but it can be debilitating and permanently reduce quality of life. Isolated cCD incidence ranges between 14% and 32% of all CD cases from the start of disease. Historically, extensive resection has been linked with longer disease-free intervals, and reduced repeat surgeries compared with segmental resections. However, most of the data have included low-quality evidence and reports typically have not adequately considered the role of biologics or advances in perioperative management of patients with cCD, the authors wrote.

The Segmental Colectomy for Crohn’s disease (SCOTCH) international study included a retrospective analysis of data from six European Inflammatory Bowel Disease referral centers on patients operated on between 2000 and 2019 who had either segmental or total colectomy for cCD.

Among 687 patients (301 male; 386 female), segmental colectomy was performed in 285 (41.5%) of cases and total colectomy in 402 (58.5%). The 15-year surgical recurrence rate was 44% among patients who had TC and 27% for patients with segmental colectomy (P = .006).

The SCOTCH study found that segmental colectomy may be performed safely and effectively and reduce the need for stoma in cCD patients without increasing risk of repeat surgeries compared with total colectomy, which was the primary measure investigators studied.

The findings of this study also suggest that biologics, when used early and correctly, may allow more conservative options for cCD, with a fivefold reduction in surgical recurrence risk in patients who have one to three large bowel locations.

Morbidity and mortality were similar in the SC and TC groups.

Among the limitations of the study are that the total colectomy patients in the study had indications for total colectomy that were also higher risk factors for recurrence – for instance, perianal disease.

The authors wrote, “The differences between patients who underwent SC vs TC might have accounted for the choice of one treatment over the other. It is however difficult to obtain a homogenous population of cCD patients.” They also cite the difficulties in gathering enough patients for randomized trials.

“These findings need to be discussed with the patients, and the choice of operation should be individualised,” they concluded. “Multidisciplinary management of patients with cCD is of critical importance to achieve optimal long-term results of bowel-sparing approaches.”

Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic, who was not part of the study, told this publication the findings should be considered confirmatory rather than suggestive of practice change.

“If a patient has a limited segment of Crohn’s, for example ileocecal Crohn’s – a common phenotype – then the standard of care is a segmental resection and primary anastomosis,” he said. “If the patient has more extensive CD – perianal fistula, colonic-only CD – they’re more likely to undergo a total colectomy. This study confirms that.“

The authors and Dr. Regueiro declared no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JOURNAL OF CROHN’S AND COLITIS

Life-threatening adverse events in liver cancer less frequent with ICI therapy

(TKIs), shows a new systematic review and meta-analysis.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, found that ICIs were associated with fewer serious adverse events, such as death, illness requiring hospitalization or illness leading to disability.

The findings are based on a meta-analysis of 30 randomized clinical trials and 12,921 patients. The analysis found a greater frequency of serious adverse events among those treated with TKIs than those treated with ICIs, though the rates of less serious liver-related adverse events were similar.

“When considering objective response rates, combination therapy with atezolizumab and bevacizumab or lenvatinib alone likely offer the most promise in the neoadjuvant setting in terms of objective response and toxic effects without preventing patients from reaching surgery,” the authors wrote.

Most newly diagnosed cases of HCC are unresectable, which leads to palliative treatment. When disease is advanced, systemic treatment is generally chosen, and new options introduced in the past decade have boosted survival. Many of these approaches feature ICIs and TKIs.

HCC therapy continues to evolve, with targeted surgical and locoregional therapies like ablation and embolization, and it’s important to understand how side effects from ICIs and TKIs might impact follow-on procedures.

Neoadjuvant therapy can avoid delays to adjuvant chemotherapy that might occur due to surgical complications. Neoadjuvant therapy also has the potential to downstage the disease from advanced to resectable, and it can provide greater opportunity for patient selection based on both tumor biology and patient characteristics.

However, advanced HCC is a complicated condition. Patients typically have cirrhosis and require an adequate functional liver remnant. Neoadjuvant locoregional treatment has been studied in HCC. A systematic review of 55 studies found no significant difference in disease-free or overall survival between preoperative or postoperative transarterial chemoembolization in resectable HCC. There is some weak evidence that locoregional therapies may achieve downstaging or maintain candidacy past 6 months.

The median age of participants was 62 years. Among the included studies, on average, 84% of patients were male. The mean fraction of patients with disease originating outside the liver was 61%, and the mean percentage with microvascular invasion was 28%. A mean of 82% had stage C according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Center staging.

21% of patients who received TKIs (95% confidence interval, 16%-26%) experienced liver toxicities versus 24% (95% CI, 13%-35%) of patients receiving ICIs. Severe adverse events were more common with TKIs, with a frequency of 46% (95% CI, 40%-51%), compared with 24% of those who received ICIs (95% CI, 13%-35%).

TKIs other than sorafenib were associated with higher rates of severe adverse events (risk ratio, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07-1.44). ICIs and sorafenib had similar rates of liver toxic effects and severe adverse events.

The study has some limitations, including variations within the included studies in the way adverse events were reported, and there was variation in the inclusion criteria.

(TKIs), shows a new systematic review and meta-analysis.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, found that ICIs were associated with fewer serious adverse events, such as death, illness requiring hospitalization or illness leading to disability.

The findings are based on a meta-analysis of 30 randomized clinical trials and 12,921 patients. The analysis found a greater frequency of serious adverse events among those treated with TKIs than those treated with ICIs, though the rates of less serious liver-related adverse events were similar.

“When considering objective response rates, combination therapy with atezolizumab and bevacizumab or lenvatinib alone likely offer the most promise in the neoadjuvant setting in terms of objective response and toxic effects without preventing patients from reaching surgery,” the authors wrote.

Most newly diagnosed cases of HCC are unresectable, which leads to palliative treatment. When disease is advanced, systemic treatment is generally chosen, and new options introduced in the past decade have boosted survival. Many of these approaches feature ICIs and TKIs.

HCC therapy continues to evolve, with targeted surgical and locoregional therapies like ablation and embolization, and it’s important to understand how side effects from ICIs and TKIs might impact follow-on procedures.

Neoadjuvant therapy can avoid delays to adjuvant chemotherapy that might occur due to surgical complications. Neoadjuvant therapy also has the potential to downstage the disease from advanced to resectable, and it can provide greater opportunity for patient selection based on both tumor biology and patient characteristics.

However, advanced HCC is a complicated condition. Patients typically have cirrhosis and require an adequate functional liver remnant. Neoadjuvant locoregional treatment has been studied in HCC. A systematic review of 55 studies found no significant difference in disease-free or overall survival between preoperative or postoperative transarterial chemoembolization in resectable HCC. There is some weak evidence that locoregional therapies may achieve downstaging or maintain candidacy past 6 months.

The median age of participants was 62 years. Among the included studies, on average, 84% of patients were male. The mean fraction of patients with disease originating outside the liver was 61%, and the mean percentage with microvascular invasion was 28%. A mean of 82% had stage C according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Center staging.

21% of patients who received TKIs (95% confidence interval, 16%-26%) experienced liver toxicities versus 24% (95% CI, 13%-35%) of patients receiving ICIs. Severe adverse events were more common with TKIs, with a frequency of 46% (95% CI, 40%-51%), compared with 24% of those who received ICIs (95% CI, 13%-35%).

TKIs other than sorafenib were associated with higher rates of severe adverse events (risk ratio, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07-1.44). ICIs and sorafenib had similar rates of liver toxic effects and severe adverse events.

The study has some limitations, including variations within the included studies in the way adverse events were reported, and there was variation in the inclusion criteria.

(TKIs), shows a new systematic review and meta-analysis.

The study, which was published online in JAMA Network Open, found that ICIs were associated with fewer serious adverse events, such as death, illness requiring hospitalization or illness leading to disability.

The findings are based on a meta-analysis of 30 randomized clinical trials and 12,921 patients. The analysis found a greater frequency of serious adverse events among those treated with TKIs than those treated with ICIs, though the rates of less serious liver-related adverse events were similar.

“When considering objective response rates, combination therapy with atezolizumab and bevacizumab or lenvatinib alone likely offer the most promise in the neoadjuvant setting in terms of objective response and toxic effects without preventing patients from reaching surgery,” the authors wrote.

Most newly diagnosed cases of HCC are unresectable, which leads to palliative treatment. When disease is advanced, systemic treatment is generally chosen, and new options introduced in the past decade have boosted survival. Many of these approaches feature ICIs and TKIs.

HCC therapy continues to evolve, with targeted surgical and locoregional therapies like ablation and embolization, and it’s important to understand how side effects from ICIs and TKIs might impact follow-on procedures.

Neoadjuvant therapy can avoid delays to adjuvant chemotherapy that might occur due to surgical complications. Neoadjuvant therapy also has the potential to downstage the disease from advanced to resectable, and it can provide greater opportunity for patient selection based on both tumor biology and patient characteristics.

However, advanced HCC is a complicated condition. Patients typically have cirrhosis and require an adequate functional liver remnant. Neoadjuvant locoregional treatment has been studied in HCC. A systematic review of 55 studies found no significant difference in disease-free or overall survival between preoperative or postoperative transarterial chemoembolization in resectable HCC. There is some weak evidence that locoregional therapies may achieve downstaging or maintain candidacy past 6 months.

The median age of participants was 62 years. Among the included studies, on average, 84% of patients were male. The mean fraction of patients with disease originating outside the liver was 61%, and the mean percentage with microvascular invasion was 28%. A mean of 82% had stage C according to Barcelona Clinic Liver Center staging.

21% of patients who received TKIs (95% confidence interval, 16%-26%) experienced liver toxicities versus 24% (95% CI, 13%-35%) of patients receiving ICIs. Severe adverse events were more common with TKIs, with a frequency of 46% (95% CI, 40%-51%), compared with 24% of those who received ICIs (95% CI, 13%-35%).

TKIs other than sorafenib were associated with higher rates of severe adverse events (risk ratio, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.07-1.44). ICIs and sorafenib had similar rates of liver toxic effects and severe adverse events.

The study has some limitations, including variations within the included studies in the way adverse events were reported, and there was variation in the inclusion criteria.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

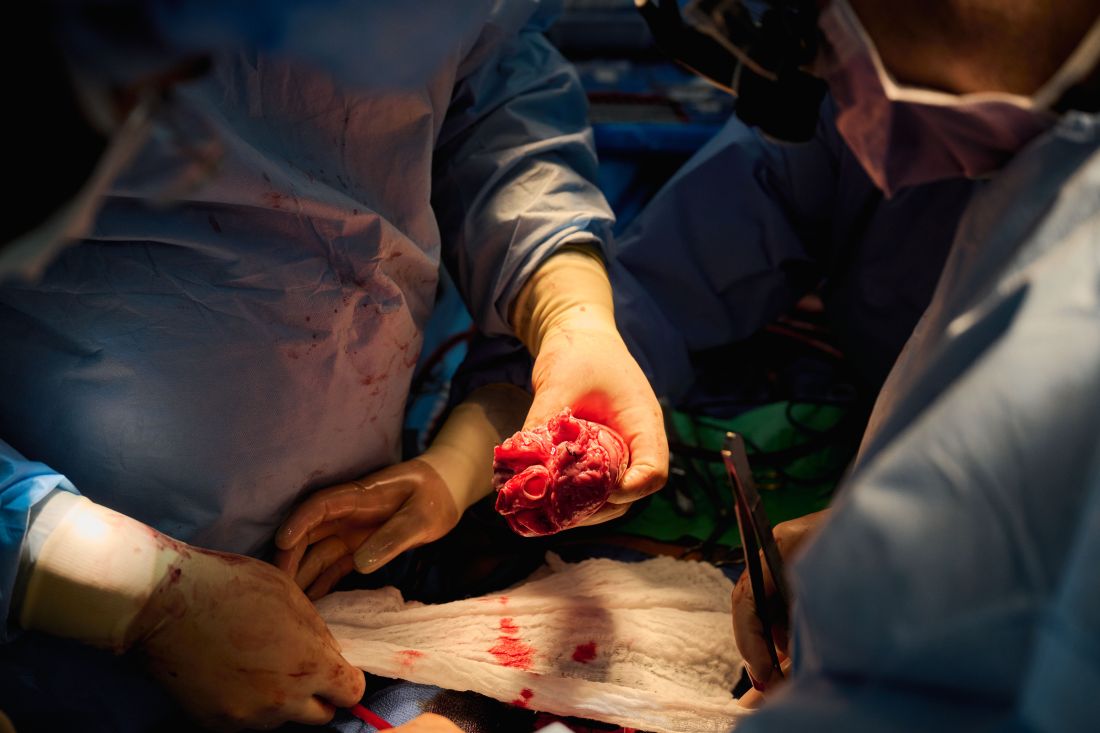

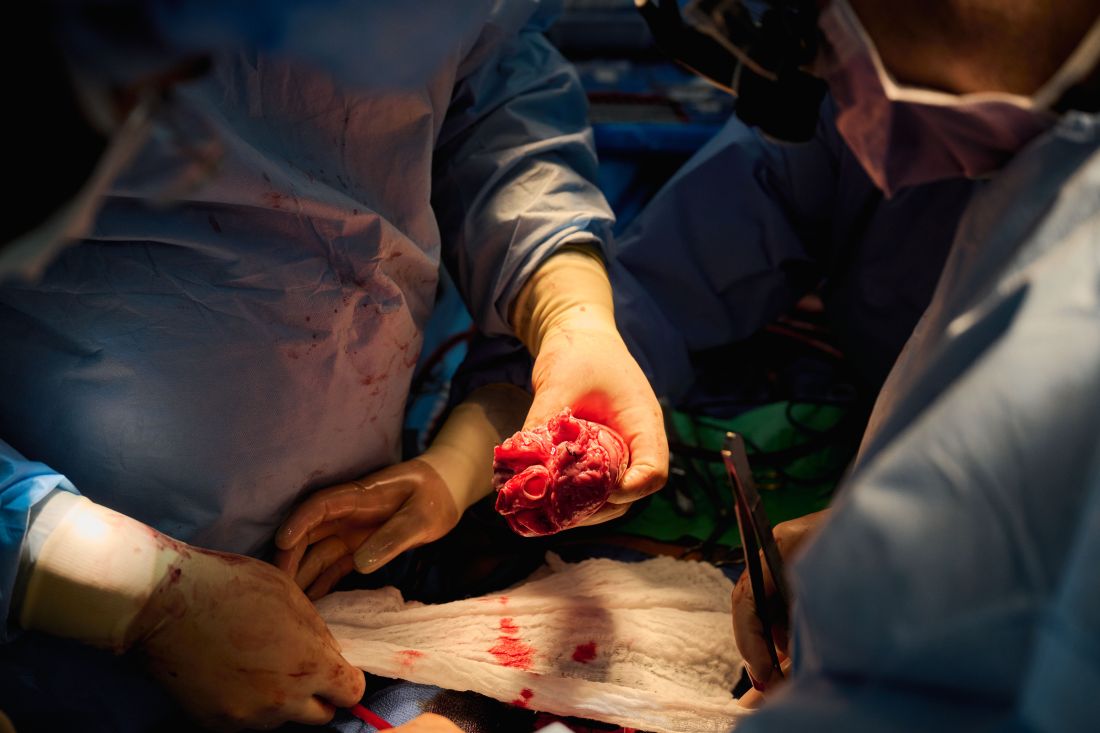

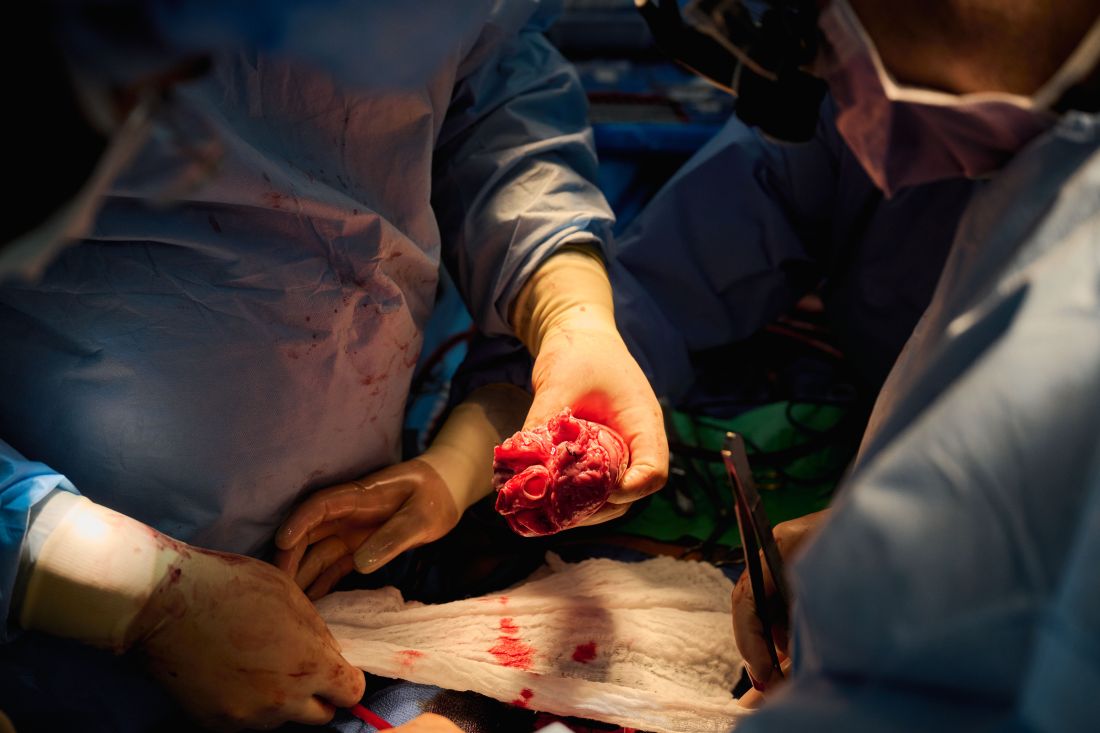

Pig heart transplants and the ethical challenges that lie ahead

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

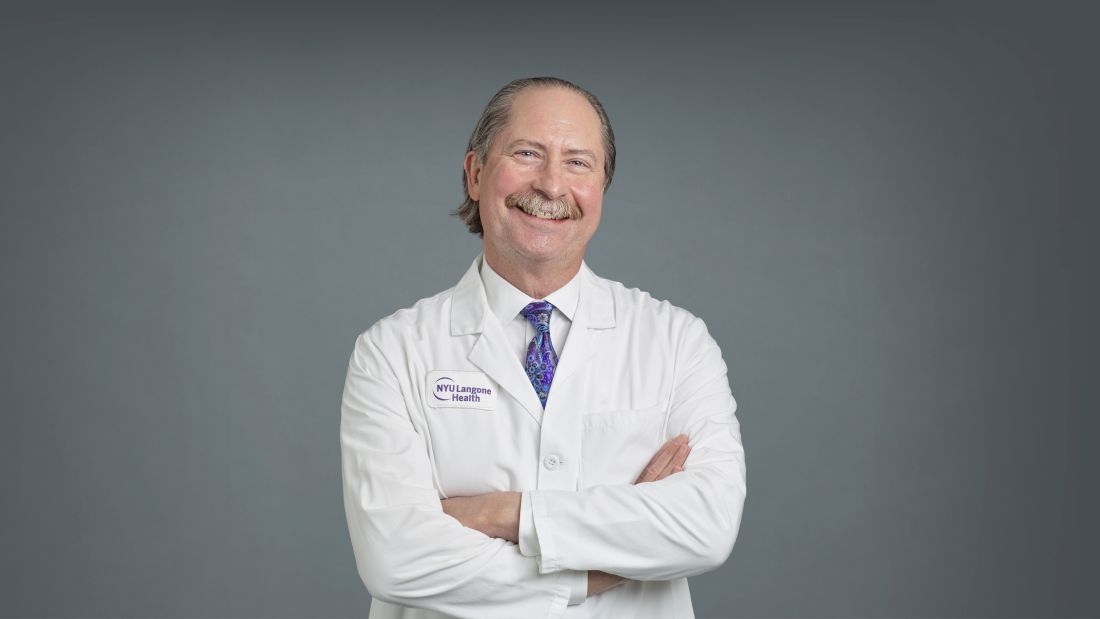

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Lung cancer treatment combo may be effective after ICI failure

In a phase 2 clinical trial, the combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor led to improved overall survival versus standard of care in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had failed previous ICI therapy.

NSCLC patients usually receive immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy at some point, whether in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, or among stage 3 patients after radiation. “The majority of patients who get diagnosed with lung cancer will get some sort of immunotherapy, and we know that at least from the advanced setting, about 15% of those will have long-term responses, which means the majority of patients will develop tumor resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” said Karen L. Reckamp, MD, who is the lead author of the study published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

That clinical need has led to the combination of ICIs with VEGF inhibitors. This approach is approved for first-line therapy of renal cell cancer, endometrial, and hepatocellular cancer. Along with its effect on tumor vasculature, VEGF inhibition assists in the activation and maturation of dendritic cells, as well as to attract cytotoxic T cells to the tumor. “By both changing the vasculature and changing the tumor milieu, there’s a potential to overcome that immune suppression and potentially overcome that (ICI) resistance,” said Dr. Reckamp, who is associate director of clinical research at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “The results of the study were encouraging. . We would like to confirm this finding in a phase 3 trial and potentially provide to patients an option that does not include chemotherapy and can potentially overcome resistance to their prior immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study included 136 patients. The median patient age was 66 years and 61% were male. The ICI/VEGF arm had better overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.69; SLR one-sided P = .05). The median overall survival was 14.5 months in the ICI/VEGF arm, versus 11.6 months in the standard care arm. Both arms had similar response rates, and grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were more common in the chemotherapy arm (60% versus 42%).

The next step is a phase 3 trial and Dr. Reckamp hopes to improve patient selection for VEGF inhibitor and VEGF receptor inhibitor therapy. “The precision medicine that’s associated with other tumor alterations has kind of been elusive for VEGF therapies, but I would hope with potentially a larger trial and understanding of some of the biomarkers that we might find a more select patient population who will benefit the most,” Dr. Reckamp said.

She also noted that the comparative arm in the phase 2 study was a combination of docetaxel and ramucirumab. “That combination has shown to be more effective than single agent docetaxel alone so [the new study] was really improved overall survival over the best standard of care therapy we have,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study was funded, in part, by Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Dr. Reckamp disclosed ties to Amgen, Tesaro, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, EMD Serono, Janssen Oncology, Merck KGaA, GlaxoSmithKline, and Mirati Therapeutics.

In a phase 2 clinical trial, the combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor led to improved overall survival versus standard of care in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had failed previous ICI therapy.

NSCLC patients usually receive immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy at some point, whether in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, or among stage 3 patients after radiation. “The majority of patients who get diagnosed with lung cancer will get some sort of immunotherapy, and we know that at least from the advanced setting, about 15% of those will have long-term responses, which means the majority of patients will develop tumor resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” said Karen L. Reckamp, MD, who is the lead author of the study published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

That clinical need has led to the combination of ICIs with VEGF inhibitors. This approach is approved for first-line therapy of renal cell cancer, endometrial, and hepatocellular cancer. Along with its effect on tumor vasculature, VEGF inhibition assists in the activation and maturation of dendritic cells, as well as to attract cytotoxic T cells to the tumor. “By both changing the vasculature and changing the tumor milieu, there’s a potential to overcome that immune suppression and potentially overcome that (ICI) resistance,” said Dr. Reckamp, who is associate director of clinical research at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “The results of the study were encouraging. . We would like to confirm this finding in a phase 3 trial and potentially provide to patients an option that does not include chemotherapy and can potentially overcome resistance to their prior immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study included 136 patients. The median patient age was 66 years and 61% were male. The ICI/VEGF arm had better overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.69; SLR one-sided P = .05). The median overall survival was 14.5 months in the ICI/VEGF arm, versus 11.6 months in the standard care arm. Both arms had similar response rates, and grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were more common in the chemotherapy arm (60% versus 42%).

The next step is a phase 3 trial and Dr. Reckamp hopes to improve patient selection for VEGF inhibitor and VEGF receptor inhibitor therapy. “The precision medicine that’s associated with other tumor alterations has kind of been elusive for VEGF therapies, but I would hope with potentially a larger trial and understanding of some of the biomarkers that we might find a more select patient population who will benefit the most,” Dr. Reckamp said.

She also noted that the comparative arm in the phase 2 study was a combination of docetaxel and ramucirumab. “That combination has shown to be more effective than single agent docetaxel alone so [the new study] was really improved overall survival over the best standard of care therapy we have,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study was funded, in part, by Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Dr. Reckamp disclosed ties to Amgen, Tesaro, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, EMD Serono, Janssen Oncology, Merck KGaA, GlaxoSmithKline, and Mirati Therapeutics.

In a phase 2 clinical trial, the combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitor led to improved overall survival versus standard of care in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who had failed previous ICI therapy.

NSCLC patients usually receive immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy at some point, whether in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting, or among stage 3 patients after radiation. “The majority of patients who get diagnosed with lung cancer will get some sort of immunotherapy, and we know that at least from the advanced setting, about 15% of those will have long-term responses, which means the majority of patients will develop tumor resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” said Karen L. Reckamp, MD, who is the lead author of the study published online in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

That clinical need has led to the combination of ICIs with VEGF inhibitors. This approach is approved for first-line therapy of renal cell cancer, endometrial, and hepatocellular cancer. Along with its effect on tumor vasculature, VEGF inhibition assists in the activation and maturation of dendritic cells, as well as to attract cytotoxic T cells to the tumor. “By both changing the vasculature and changing the tumor milieu, there’s a potential to overcome that immune suppression and potentially overcome that (ICI) resistance,” said Dr. Reckamp, who is associate director of clinical research at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “The results of the study were encouraging. . We would like to confirm this finding in a phase 3 trial and potentially provide to patients an option that does not include chemotherapy and can potentially overcome resistance to their prior immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study included 136 patients. The median patient age was 66 years and 61% were male. The ICI/VEGF arm had better overall survival (hazard ratio, 0.69; SLR one-sided P = .05). The median overall survival was 14.5 months in the ICI/VEGF arm, versus 11.6 months in the standard care arm. Both arms had similar response rates, and grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events were more common in the chemotherapy arm (60% versus 42%).

The next step is a phase 3 trial and Dr. Reckamp hopes to improve patient selection for VEGF inhibitor and VEGF receptor inhibitor therapy. “The precision medicine that’s associated with other tumor alterations has kind of been elusive for VEGF therapies, but I would hope with potentially a larger trial and understanding of some of the biomarkers that we might find a more select patient population who will benefit the most,” Dr. Reckamp said.

She also noted that the comparative arm in the phase 2 study was a combination of docetaxel and ramucirumab. “That combination has shown to be more effective than single agent docetaxel alone so [the new study] was really improved overall survival over the best standard of care therapy we have,” Dr. Reckamp said.

The study was funded, in part, by Eli Lilly and Company and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Dr. Reckamp disclosed ties to Amgen, Tesaro, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Genentech, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, EMD Serono, Janssen Oncology, Merck KGaA, GlaxoSmithKline, and Mirati Therapeutics.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

CAR T-cell therapy turns 10 and finally earns the word ‘cure’

Ten years ago, Stephan Grupp, MD, PhD, plunged into an unexplored area of pediatric cancer treatment with a 6-year-old patient for whom every treatment available for her acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had been exhausted.

Dr. Grupp, a pioneer in cellular immunotherapy at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, had just got the green light to launch the first phase 1 trial of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for children.

“The trial opened at the absolute last possible moment that it could have been helpful to her,” he said in an interview. “There was nothing else to do to temporize her further. ... It had to open then or never.”

The patient was Emily Whitehead, who has since become a poster girl for the dramatic results that can be achieved with these novel therapies. After that one CAR T-cell treatment back in 2012, she has been free of her leukemia and has remained in remission for more than 10 years.

Dr. Grupp said that he is, at last, starting to use the “cure” word.

“I’m not just a doctor, I’m a scientist – and one case isn’t enough to have confidence about anything,” he said. “We wanted more patients to be out longer to be able to say that thing which we have for a long time called the ‘c word.’

“CAR T-cell therapy has now been given to hundreds of patients at CHOP, and – we are unique in this – we have a couple dozen patients who are 5, 6, 7, 9 years out or more without further therapy. That feels like a cure to me,” he commented.

First patient with ALL

Emily was the first patient with ALL to receive the novel treatment, and also the first child.

There was a precedent, however. After having been “stuck” for decades, the CAR T-cell field had recently made a breakthrough, thanks to research by Dr. Grupp’s colleague Carl June, MD, and associates at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. By tweaking two key steps in the genetic modification of T cells, Dr. June’s team had successfully treated three adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), two of whom were in complete remission.

But using the treatment for a child and for a different type of leukemia was a daunting prospect. Dr. Grupp said that he was candid with Emily’s parents, Tom and Kari Whitehead, emphasizing that there are no guarantees in cancer treatment, particularly in a phase 1 trial.

But the Whiteheads had no time to waste and nowhere else to turn. Her father, Tom, recalled saying: “This is something outside the box, this is going to give her a chance.”

Dr. Grupp, who described himself as being “on the cowboy end” of oncology care, was ready to take the plunge.

Little did any of them know that the treatment would make Emily even sicker than she already was, putting her in intensive care. But thanks to a combination of several lucky breaks and a lot of brain power, she would make a breathtakingly rapid recovery.

The ‘magic formula’

CAR T-cell therapy involves harvesting a patient’s T cells and modifying them in the lab with a chimeric antigen receptor to target CD19, a protein found on the surface of ALL cancer cells.

Before the University of Pennsylvania team tweaked the process, clinical trials of the therapy yielded only modest results because the modified T cells “were very powerful in the short term but had almost no proliferative capacity” once they were infused back into the patient, Dr. Grupp explained.

“It does not matter how many cells you give to a patient, what matters is that the cells grow in the patient to the level needed to control the leukemia,” he said.

Dr. June’s team came up with what Dr. Grupp calls “the magic formula”: A bead-based manufacturing process that produced younger T-cell phenotypes with “enormous” proliferative capacity, and a lentiviral approach to the genetic modification, enabling prolonged expression of the CAR-T molecule.

“Was it rogue? Absolutely, positively not,” said Dr. Grupp, thinking back to the day he enrolled Emily in the trial. “Was it risky? Obviously ... we all dived into this pool without knowing what was under the water, so I would say, rogue, no, risky, yes. And I would say we didn’t know nearly enough about the risks.”

Cytokine storm

The gravest risk that Dr. Grupp and his team encountered was something they had not anticipated. At the time, they had no name for it.

The three adults with CLL who had received CAR T-cell therapy had experienced a mild version that the researchers referred to as “tumor lysis syndrome”.

But for Emily, on day 3 of her CAR T-cell infusion, there was a ferocious reaction storm that later came to be called cytokine release syndrome.

“The wheels just came off then,” said Mr. Whitehead. “I remember her blood pressure was 53 over 29. They took her to the ICU, induced a coma, and put her on a ventilator. It was brutal to watch. The oscillatory ventilator just pounds on you, and there was blood bubbling out around the hose in her mouth.

“I remember the third or fourth night, a doctor took me in the hallway and said, ‘There’s a one-in-a-thousand chance your daughter is alive when the sun comes up,’” Mr. Whitehead said in an interview. “And I said: ‘All right, I’ll see you at rounds tomorrow, because she’ll still be here.’ ”

“We had some vague notion of toxicity ... but it turned out not nearly enough,” said Dr. Grupp. The ICU “worked flat out” to save her life. “They had deployed everything they had to keep a human being alive and they had nothing more to add. At some point, you run out of things that you can do, and we had run out.”

On the fly

It was then that the team ran into some good luck. The first break was when they decided to look at her cytokines. “Our whole knowledge base came together in the moment, on the fly, at the exact moment when Emily was so very sick,” he recalled. “Could we get the result fast enough? The lab dropped everything to run the test.”

They ordered a broad cytokine panel that included 30 analytes. The results showed that a number of cytokines “were just unbelievably elevated,” he said. Among them was interleukin-6.

“IL-6 isn’t even made by T cells, so nobody in the world would have guessed that this would have mattered. If we’d ordered a smaller panel, it might not even have been on it. Yet this was the one cytokine we had a drug for – tocilizumab – so that was chance. And then, another chance was that the drug was at the hospital, because there are rheumatology patients who get it.

“So, we went from making the determination that IL-6 was high and figuring out there was a drug for it at 3:00 o’clock to giving the drug to her at 8:00 o’clock, and then her clinical situation turned around so quickly – I mean hours later.”

Emily woke up from a 14-day medically induced coma on her seventh birthday.

Eight days later, her bone marrow showed complete remission. “The doctors said, ‘We’ve never seen anyone this sick get better any faster,’ ” Mr. Whitehead said.

She had already been through a battery of treatments for her leukemia. “It was 22 months of failed, standard treatment, and then just 23 days after they gave her the first dose of CAR T-cells that she was cancer free,” he added.

Talking about ‘cure’

Now that Emily, 17, has remained in remission for 10 years, Dr. Grupp is finally willing to use the word “cure” – but it has taken him a long time.

Now, he says, the challenge from the bedside is to keep parents’ and patients’ expectations realistic about what they see as a miracle cure.

“It’s not a miracle. We can get patients into remission 90-plus percent of the time – but some patients do relapse – and then there are the risks [of the cytokine storm, which can be life-threatening].

“Right now, our experience is that about 12% of patients end up in the ICU, but they hardly ever end up as sick as Emily ... because now we’re giving the tocilizumab much earlier,” Dr. Grupp said.

Hearing whispers

Since their daughter’s recovery, Tom and Kari Whitehead have dedicated much of their time to spreading the word about the treatment that saved Emily’s life. Mr. Whitehead testified at the Food and Drug Administration’s advisory committee meeting in 2017 when approval was being considered for the CAR T-cell product that Emily received. The product was tisagenlecleucel-T (Novartis); at that meeting, there was a unanimous vote to recommend approval. This was the first CAR T cell to reach the market.

As cofounders of the Emily Whitehead Foundation, Emily’s parents have helped raise more than $2 million to support research in the field, and they travel around the world telling their story to “move this revolution forward.”

Despite their fierce belief in the science that saved Emily, they also acknowledge there was luck – and faith. Early in their journey, when Emily experienced relapse after her initial treatments, Mr. Whitehead drew comfort from two visions, which he calls “whispers,” that guided them through several forks in the road and through tough decisions about Emily’s treatment.

Several times the parents refused treatment that was offered to Emily, and once they had her discharged against medical advice. “I told Kari she’s definitely going to beat her cancer – I saw it. I don’t know how it’s going to happen, but we’re going to be in the bone marrow transplant hallway [at CHOP] teaching her to walk again. I know a lot of doctors don’t want to hear anything about ‘a sign,’ or what guided us, but I don’t think you have to separate faith and science, I think it takes everything to make something like this to happen.”

Enduring effect

The key to the CAR T-cell breakthrough that gave rise to Emily’s therapy was cell proliferation, and the effect is enduring, beyond all expectations, said Dr. Grupp. The modified T cells are still detectable in Emily and other patients in long-term remission.

“The fundamental question is, are the cells still working, or are the patients cured and they don’t need them?” said Dr. Grupp. “I think it’s the latter. The data that we have from several large datasets that we developed with Novartis are that, if you get to a year and your minimal residual disease testing both by flow and by next-generation sequencing is negative and you still have B-cell aplasia, the relapse risk is close to zero at that point.”

While it’s still not clear if and when that risk will ever get to zero, Emily and Dr. Grupp have successfully closed the chapter.

“Oncologists have different notions of what the word ‘cure’ means. If your attitude is you’re not cured until you’ve basically reached the end of your life and you haven’t relapsed, well, that’s an impossible bar to hit. My attitude is, if your likelihood of having a disease recurrence is lower than the other risks in your life, like getting into your car and driving to your appointment, then that’s what a functional cure looks like,” he said.

“I’m probably the doctor that still sees her the most, but honestly, the whole conversation is not about leukemia at all. She has B-cell aplasia, so we have to treat that, and then it’s about making sure there’s no long-term side effects from the totality of her treatment. Generally, for a patient who’s gotten a moderate amount of chemotherapy and CAR T, that should not interfere with fertility. Has any patient in the history of the world ever relapsed more than 5 years out from their therapy? Of course. Is that incredibly rare? Yes, it is. You can be paralyzed by that, or you can compartmentalize it.”

As for the Whiteheads, they are focused on Emily’s college applications, her new driver’s license, and her project to cowrite a film about her story with a Hollywood filmmaker.

Mr. Whitehead said the one thing he hopes clinicians take away from their story is that sometimes a parent’s instinct transcends science.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ten years ago, Stephan Grupp, MD, PhD, plunged into an unexplored area of pediatric cancer treatment with a 6-year-old patient for whom every treatment available for her acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had been exhausted.

Dr. Grupp, a pioneer in cellular immunotherapy at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, had just got the green light to launch the first phase 1 trial of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for children.

“The trial opened at the absolute last possible moment that it could have been helpful to her,” he said in an interview. “There was nothing else to do to temporize her further. ... It had to open then or never.”

The patient was Emily Whitehead, who has since become a poster girl for the dramatic results that can be achieved with these novel therapies. After that one CAR T-cell treatment back in 2012, she has been free of her leukemia and has remained in remission for more than 10 years.

Dr. Grupp said that he is, at last, starting to use the “cure” word.

“I’m not just a doctor, I’m a scientist – and one case isn’t enough to have confidence about anything,” he said. “We wanted more patients to be out longer to be able to say that thing which we have for a long time called the ‘c word.’

“CAR T-cell therapy has now been given to hundreds of patients at CHOP, and – we are unique in this – we have a couple dozen patients who are 5, 6, 7, 9 years out or more without further therapy. That feels like a cure to me,” he commented.

First patient with ALL

Emily was the first patient with ALL to receive the novel treatment, and also the first child.

There was a precedent, however. After having been “stuck” for decades, the CAR T-cell field had recently made a breakthrough, thanks to research by Dr. Grupp’s colleague Carl June, MD, and associates at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. By tweaking two key steps in the genetic modification of T cells, Dr. June’s team had successfully treated three adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), two of whom were in complete remission.

But using the treatment for a child and for a different type of leukemia was a daunting prospect. Dr. Grupp said that he was candid with Emily’s parents, Tom and Kari Whitehead, emphasizing that there are no guarantees in cancer treatment, particularly in a phase 1 trial.

But the Whiteheads had no time to waste and nowhere else to turn. Her father, Tom, recalled saying: “This is something outside the box, this is going to give her a chance.”

Dr. Grupp, who described himself as being “on the cowboy end” of oncology care, was ready to take the plunge.

Little did any of them know that the treatment would make Emily even sicker than she already was, putting her in intensive care. But thanks to a combination of several lucky breaks and a lot of brain power, she would make a breathtakingly rapid recovery.

The ‘magic formula’

CAR T-cell therapy involves harvesting a patient’s T cells and modifying them in the lab with a chimeric antigen receptor to target CD19, a protein found on the surface of ALL cancer cells.

Before the University of Pennsylvania team tweaked the process, clinical trials of the therapy yielded only modest results because the modified T cells “were very powerful in the short term but had almost no proliferative capacity” once they were infused back into the patient, Dr. Grupp explained.

“It does not matter how many cells you give to a patient, what matters is that the cells grow in the patient to the level needed to control the leukemia,” he said.

Dr. June’s team came up with what Dr. Grupp calls “the magic formula”: A bead-based manufacturing process that produced younger T-cell phenotypes with “enormous” proliferative capacity, and a lentiviral approach to the genetic modification, enabling prolonged expression of the CAR-T molecule.

“Was it rogue? Absolutely, positively not,” said Dr. Grupp, thinking back to the day he enrolled Emily in the trial. “Was it risky? Obviously ... we all dived into this pool without knowing what was under the water, so I would say, rogue, no, risky, yes. And I would say we didn’t know nearly enough about the risks.”

Cytokine storm

The gravest risk that Dr. Grupp and his team encountered was something they had not anticipated. At the time, they had no name for it.

The three adults with CLL who had received CAR T-cell therapy had experienced a mild version that the researchers referred to as “tumor lysis syndrome”.

But for Emily, on day 3 of her CAR T-cell infusion, there was a ferocious reaction storm that later came to be called cytokine release syndrome.

“The wheels just came off then,” said Mr. Whitehead. “I remember her blood pressure was 53 over 29. They took her to the ICU, induced a coma, and put her on a ventilator. It was brutal to watch. The oscillatory ventilator just pounds on you, and there was blood bubbling out around the hose in her mouth.