User login

NAMDRC Update

The old adage of not wanting to see how laws or sausage is made holds true today, perhaps more so than ever. But certain clinical realities within pulmonary medicine virtually ensure that legislation is actually part of any reasonable solution.

NAMDRC has initiated an outreach to all the key medical, allied health, and patient societies that focus on pulmonary medicine to determine if consensus can be reached on a focused laundry list of issues that, for varying reasons, lean toward Congress for legislative solutions.

Here is a list of some of the issues under discussion:

• Home mechanical ventilation. Under current law, “ventilators” are covered items under the durable medical equipment benefit. In the 1990s, in order to circumvent statutory requirements that ventilators be paid under a “frequent and substantial servicing” payment methodology, HCFA (now CMS) created a new category – respiratory assist devices and declared that these devices, despite classification by FDA as ventilators, are not ventilators in reality, and the payment methodology, therefore, does not apply.

Over the past several years, the pulmonary medicine community tried its best to convince CMS that its rules were problematic, archaic, and costing the Medicare program tens of millions of dollars in unnecessary expenditures. A formal submission to CMS, a request for a National Coverage Determination reconsideration, was denied with a phrase now echoed throughout health care, “it’s complicated.” The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• High flow oxygen therapy for ILD patients. Oxygen remains the largest single component of the durable medical equipment benefit and, largely due to competitive bidding, has seen payment drop dramatically since the implementation of competitive bidding.

One can easily argue that competitive pricing is self-inflicted by the DME industry as the rates are set through a complicated formula based on bids from suppliers. But the impact has been particularly hard on liquid systems, the delivery system choice of not only many Medicare beneficiaries but also is the modality of choice for patients with clear need for high flow oxygen. While delivery in the home for high flow needs can be met by some stationary concentrators, the virtual disappearance of liquid systems, attributable to pricing triggered by competitive bidding, results in many ILD patients unable to leave their homes. The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• Section 603. This provision of the Balanced Budget Act of 2015 was designed to inhibit hospital purchases of certain physician practices that were based on aberrations within the Medicare payment system that rewarded hospitals significantly more than the same service provided in a physician office. For example, a physician office-based sleep lab may be able to bill Medicare for a particular service, but if the hospital purchases that physician practice and bills for the same service, it might receive upwards of twice as much payment.

While all involved seem to agree that this provision was not intended to target pulmonary rehabilitation services, it is being hit particularly hard by CMS rules implementing the statute. Any new pulmonary rehab program that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus must bill at the physician fee schedule rate, a rate about half of the hospital outpatient rate. Furthermore, existing programs that choose to expand must do so within the confines of their specific current location, unable to move a floor away. Doing so would trigger the reduced payment methodology.

[[{"fid":"197721","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]

CMS agrees this is clearly an example of unintended consequences, but CMS also acknowledges it does not have the authority to remedy the situation. The agency itself signaled the only way to exempt pulmonary rehabilitation services is to seek Congressional action.

And now to the “sausage” part of the equation. Congressional action on virtually anything except renaming a post office becomes a political, as well as substantive, challenge. Here are just some of the considerations that must be addressed by any legislative strategy.

1. Any “fix” must be clinically sound and supported across a broad cross section of physician and patient groups. And the fix must give some level of flexibility to CMS to implement it in a reasonable way but tie their hands to force changes in policy.

2. Any “fix” must have a strong political strategy that can muster support within key Congressional committees (House Ways & Means Committee and Energy & Commerce Committee, along with the Senate Finance Committee, let alone 218 votes in the House and 51 votes in the Senate.

Given these issues, almost regardless of the political environment, it is time to begin working on substantive solutions so that when the political climate improves, pulmonary medicine is ready to move forward with a coordinated cohesive strategy.

The old adage of not wanting to see how laws or sausage is made holds true today, perhaps more so than ever. But certain clinical realities within pulmonary medicine virtually ensure that legislation is actually part of any reasonable solution.

NAMDRC has initiated an outreach to all the key medical, allied health, and patient societies that focus on pulmonary medicine to determine if consensus can be reached on a focused laundry list of issues that, for varying reasons, lean toward Congress for legislative solutions.

Here is a list of some of the issues under discussion:

• Home mechanical ventilation. Under current law, “ventilators” are covered items under the durable medical equipment benefit. In the 1990s, in order to circumvent statutory requirements that ventilators be paid under a “frequent and substantial servicing” payment methodology, HCFA (now CMS) created a new category – respiratory assist devices and declared that these devices, despite classification by FDA as ventilators, are not ventilators in reality, and the payment methodology, therefore, does not apply.

Over the past several years, the pulmonary medicine community tried its best to convince CMS that its rules were problematic, archaic, and costing the Medicare program tens of millions of dollars in unnecessary expenditures. A formal submission to CMS, a request for a National Coverage Determination reconsideration, was denied with a phrase now echoed throughout health care, “it’s complicated.” The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• High flow oxygen therapy for ILD patients. Oxygen remains the largest single component of the durable medical equipment benefit and, largely due to competitive bidding, has seen payment drop dramatically since the implementation of competitive bidding.

One can easily argue that competitive pricing is self-inflicted by the DME industry as the rates are set through a complicated formula based on bids from suppliers. But the impact has been particularly hard on liquid systems, the delivery system choice of not only many Medicare beneficiaries but also is the modality of choice for patients with clear need for high flow oxygen. While delivery in the home for high flow needs can be met by some stationary concentrators, the virtual disappearance of liquid systems, attributable to pricing triggered by competitive bidding, results in many ILD patients unable to leave their homes. The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• Section 603. This provision of the Balanced Budget Act of 2015 was designed to inhibit hospital purchases of certain physician practices that were based on aberrations within the Medicare payment system that rewarded hospitals significantly more than the same service provided in a physician office. For example, a physician office-based sleep lab may be able to bill Medicare for a particular service, but if the hospital purchases that physician practice and bills for the same service, it might receive upwards of twice as much payment.

While all involved seem to agree that this provision was not intended to target pulmonary rehabilitation services, it is being hit particularly hard by CMS rules implementing the statute. Any new pulmonary rehab program that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus must bill at the physician fee schedule rate, a rate about half of the hospital outpatient rate. Furthermore, existing programs that choose to expand must do so within the confines of their specific current location, unable to move a floor away. Doing so would trigger the reduced payment methodology.

[[{"fid":"197721","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]

CMS agrees this is clearly an example of unintended consequences, but CMS also acknowledges it does not have the authority to remedy the situation. The agency itself signaled the only way to exempt pulmonary rehabilitation services is to seek Congressional action.

And now to the “sausage” part of the equation. Congressional action on virtually anything except renaming a post office becomes a political, as well as substantive, challenge. Here are just some of the considerations that must be addressed by any legislative strategy.

1. Any “fix” must be clinically sound and supported across a broad cross section of physician and patient groups. And the fix must give some level of flexibility to CMS to implement it in a reasonable way but tie their hands to force changes in policy.

2. Any “fix” must have a strong political strategy that can muster support within key Congressional committees (House Ways & Means Committee and Energy & Commerce Committee, along with the Senate Finance Committee, let alone 218 votes in the House and 51 votes in the Senate.

Given these issues, almost regardless of the political environment, it is time to begin working on substantive solutions so that when the political climate improves, pulmonary medicine is ready to move forward with a coordinated cohesive strategy.

The old adage of not wanting to see how laws or sausage is made holds true today, perhaps more so than ever. But certain clinical realities within pulmonary medicine virtually ensure that legislation is actually part of any reasonable solution.

NAMDRC has initiated an outreach to all the key medical, allied health, and patient societies that focus on pulmonary medicine to determine if consensus can be reached on a focused laundry list of issues that, for varying reasons, lean toward Congress for legislative solutions.

Here is a list of some of the issues under discussion:

• Home mechanical ventilation. Under current law, “ventilators” are covered items under the durable medical equipment benefit. In the 1990s, in order to circumvent statutory requirements that ventilators be paid under a “frequent and substantial servicing” payment methodology, HCFA (now CMS) created a new category – respiratory assist devices and declared that these devices, despite classification by FDA as ventilators, are not ventilators in reality, and the payment methodology, therefore, does not apply.

Over the past several years, the pulmonary medicine community tried its best to convince CMS that its rules were problematic, archaic, and costing the Medicare program tens of millions of dollars in unnecessary expenditures. A formal submission to CMS, a request for a National Coverage Determination reconsideration, was denied with a phrase now echoed throughout health care, “it’s complicated.” The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• High flow oxygen therapy for ILD patients. Oxygen remains the largest single component of the durable medical equipment benefit and, largely due to competitive bidding, has seen payment drop dramatically since the implementation of competitive bidding.

One can easily argue that competitive pricing is self-inflicted by the DME industry as the rates are set through a complicated formula based on bids from suppliers. But the impact has been particularly hard on liquid systems, the delivery system choice of not only many Medicare beneficiaries but also is the modality of choice for patients with clear need for high flow oxygen. While delivery in the home for high flow needs can be met by some stationary concentrators, the virtual disappearance of liquid systems, attributable to pricing triggered by competitive bidding, results in many ILD patients unable to leave their homes. The only effective solution is a legislative one.

• Section 603. This provision of the Balanced Budget Act of 2015 was designed to inhibit hospital purchases of certain physician practices that were based on aberrations within the Medicare payment system that rewarded hospitals significantly more than the same service provided in a physician office. For example, a physician office-based sleep lab may be able to bill Medicare for a particular service, but if the hospital purchases that physician practice and bills for the same service, it might receive upwards of twice as much payment.

While all involved seem to agree that this provision was not intended to target pulmonary rehabilitation services, it is being hit particularly hard by CMS rules implementing the statute. Any new pulmonary rehab program that is not within 250 yards of the main hospital campus must bill at the physician fee schedule rate, a rate about half of the hospital outpatient rate. Furthermore, existing programs that choose to expand must do so within the confines of their specific current location, unable to move a floor away. Doing so would trigger the reduced payment methodology.

[[{"fid":"197721","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"plain_text","field_file_image_credit[und][0][format]":"plain_text"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1","format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"Phil Porte","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":""}}}]]

CMS agrees this is clearly an example of unintended consequences, but CMS also acknowledges it does not have the authority to remedy the situation. The agency itself signaled the only way to exempt pulmonary rehabilitation services is to seek Congressional action.

And now to the “sausage” part of the equation. Congressional action on virtually anything except renaming a post office becomes a political, as well as substantive, challenge. Here are just some of the considerations that must be addressed by any legislative strategy.

1. Any “fix” must be clinically sound and supported across a broad cross section of physician and patient groups. And the fix must give some level of flexibility to CMS to implement it in a reasonable way but tie their hands to force changes in policy.

2. Any “fix” must have a strong political strategy that can muster support within key Congressional committees (House Ways & Means Committee and Energy & Commerce Committee, along with the Senate Finance Committee, let alone 218 votes in the House and 51 votes in the Senate.

Given these issues, almost regardless of the political environment, it is time to begin working on substantive solutions so that when the political climate improves, pulmonary medicine is ready to move forward with a coordinated cohesive strategy.

Florence A. Blanchfield: A Lifetime of Nursing Leadership

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

Abstracts Presented at the 2017 AVAHO Annual Meeting (Digital Edition)

Student Hospitalist Scholars: The importance of shared mental models

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

As I walk the University of Chicago Hospital observing various health care practitioners, I am continually impressed with the businesslike approach and productivity of each individual. The hospital staff is composed of highly intelligent, experienced, and talented physicians, but I have come to understand that in this large system it can be difficult to maintain quality patient care with both increased census and increased handoffs.

The research project I am working on focuses on shared mental models between the MICU and the general floor on what the most important factor of care is while they are on the floor, and to identify how prominent it is for shared mental models to be present between the transferring and receiving teams. After reading various papers, I am beginning to understand the various complexities present in translating information when transferring patients from any department onto the floor.

I continue to discuss these topics with my mentors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, in order to appropriately categorize all survey responses and identify whether there is concordance between teams. I am glad to be able to rely on their insight concerning methods of coding the data, as well as what type of medical care each responding individual receives, and remaining on track with my estimated timeline of completion.

Past research supports the idea that increased times, distractions, and workloads in regard to handoffs result in potential errors, decreasing the quality of patient care and potentially resulting in worse patient outcomes. MICU patients are at a particular risk, since ineffective communication could lead to readmission, which could result in worsened health outcomes.

I believe that this current research project is highly significant since it highlights whether effective communication is occurring in the first place, and whether teams are appropriately communicating patient plans for this group of higher-acuity patients. As I continue my research at the university, I hope to further identify whether effective communication is taking place for this at-risk group of floor patients.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

As I walk the University of Chicago Hospital observing various health care practitioners, I am continually impressed with the businesslike approach and productivity of each individual. The hospital staff is composed of highly intelligent, experienced, and talented physicians, but I have come to understand that in this large system it can be difficult to maintain quality patient care with both increased census and increased handoffs.

The research project I am working on focuses on shared mental models between the MICU and the general floor on what the most important factor of care is while they are on the floor, and to identify how prominent it is for shared mental models to be present between the transferring and receiving teams. After reading various papers, I am beginning to understand the various complexities present in translating information when transferring patients from any department onto the floor.

I continue to discuss these topics with my mentors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, in order to appropriately categorize all survey responses and identify whether there is concordance between teams. I am glad to be able to rely on their insight concerning methods of coding the data, as well as what type of medical care each responding individual receives, and remaining on track with my estimated timeline of completion.

Past research supports the idea that increased times, distractions, and workloads in regard to handoffs result in potential errors, decreasing the quality of patient care and potentially resulting in worse patient outcomes. MICU patients are at a particular risk, since ineffective communication could lead to readmission, which could result in worsened health outcomes.

I believe that this current research project is highly significant since it highlights whether effective communication is occurring in the first place, and whether teams are appropriately communicating patient plans for this group of higher-acuity patients. As I continue my research at the university, I hope to further identify whether effective communication is taking place for this at-risk group of floor patients.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

As I walk the University of Chicago Hospital observing various health care practitioners, I am continually impressed with the businesslike approach and productivity of each individual. The hospital staff is composed of highly intelligent, experienced, and talented physicians, but I have come to understand that in this large system it can be difficult to maintain quality patient care with both increased census and increased handoffs.

The research project I am working on focuses on shared mental models between the MICU and the general floor on what the most important factor of care is while they are on the floor, and to identify how prominent it is for shared mental models to be present between the transferring and receiving teams. After reading various papers, I am beginning to understand the various complexities present in translating information when transferring patients from any department onto the floor.

I continue to discuss these topics with my mentors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, in order to appropriately categorize all survey responses and identify whether there is concordance between teams. I am glad to be able to rely on their insight concerning methods of coding the data, as well as what type of medical care each responding individual receives, and remaining on track with my estimated timeline of completion.

Past research supports the idea that increased times, distractions, and workloads in regard to handoffs result in potential errors, decreasing the quality of patient care and potentially resulting in worse patient outcomes. MICU patients are at a particular risk, since ineffective communication could lead to readmission, which could result in worsened health outcomes.

I believe that this current research project is highly significant since it highlights whether effective communication is occurring in the first place, and whether teams are appropriately communicating patient plans for this group of higher-acuity patients. As I continue my research at the university, I hope to further identify whether effective communication is taking place for this at-risk group of floor patients.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

In Hodgkin lymphoma, HAPLO transplant outcomes match those of conventional transplants

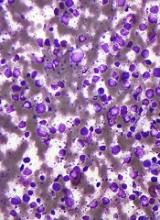

Hodgkin lymphoma patients who received haploidentical (HAPLO) allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after a nonmyeloablative regimen and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide had outcomes similar to those of patients who had conventional transplants, in a retrospective analysis of 709 adult patients in the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation database.

In addition, patients who underwent HAPLO had a lower incidence of extensive chronic graft-versus host disease (cGVHD) compared with HLA-matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplantation and higher cGVHD-free/relapse-free survival compared with HLA-matched sibling donor (SIB) transplantation.

“Use of HAPLO donors may allow patients to proceed more rapidly to transplantation, avoiding the time needed to complete a formal MUD search and arrange for graft collection at a remote center,” wrote Carmen Martinez, MD, of the Institute of Hematology and Oncology, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona. The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Conventional donors are unavailable for a significant proportion of Hodgkin lymphoma patients.

Recommendations from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation consider alloHCT to be the standard treatment option for eligible patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who have relapsed after undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation and SIB or MUD. For the retrospective study, outcomes were compared for 338 patients who had SIB transplants, 273 patients who had MUD transplants, and 98 patients who received HAPLO transplants after a nonmyeloablative regimen and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy) as GVHD prophylaxis.

The rate of grade II-IV acute GVHD after HAPLO was higher than after SIB (33% vs. 18%; P = .003), and was comparable to the rate with MUD (30%). The rates of grade III-IV acute GVHD were similar for all three cohorts (HAPLO, 9%; SIB, 6%; and MUD, 9%).

At 1 year, the cumulative rate of chronic GVHD was 26% after HAPLO and 25% after SIB; it was significantly higher at 41% after MUD (P = .017).

The cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality at 1 year was 17% with HAPLO, 13% with SIB, and significantly higher at 21% with MUD (P = .003). At 2 years, the cumulative incidence of relapse or progression was 39%, 49%, and 32%, respectively. The difference was significantly higher for SIB than HAPLO (P = .047) and MUD (P = .001).

There were no significant differences in 2-year overall survival, but MUD transplant recipients had lower overall survival (62%; 95% CI, 56 to 68; P = .039) compared with SIB transplant recipients.

“Whether HAPLO transplantation is the first choice instead of MUD transplantation and whether it can eventually substitute SIB transplantation in specific subgroups of patients must be assessed within the context of a randomized prospective clinical trial,” wrote Dr. Martinez and colleagues.

Hodgkin lymphoma patients who received haploidentical (HAPLO) allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after a nonmyeloablative regimen and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide had outcomes similar to those of patients who had conventional transplants, in a retrospective analysis of 709 adult patients in the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation database.

In addition, patients who underwent HAPLO had a lower incidence of extensive chronic graft-versus host disease (cGVHD) compared with HLA-matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplantation and higher cGVHD-free/relapse-free survival compared with HLA-matched sibling donor (SIB) transplantation.

“Use of HAPLO donors may allow patients to proceed more rapidly to transplantation, avoiding the time needed to complete a formal MUD search and arrange for graft collection at a remote center,” wrote Carmen Martinez, MD, of the Institute of Hematology and Oncology, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona. The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Conventional donors are unavailable for a significant proportion of Hodgkin lymphoma patients.

Recommendations from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation consider alloHCT to be the standard treatment option for eligible patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who have relapsed after undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation and SIB or MUD. For the retrospective study, outcomes were compared for 338 patients who had SIB transplants, 273 patients who had MUD transplants, and 98 patients who received HAPLO transplants after a nonmyeloablative regimen and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy) as GVHD prophylaxis.

The rate of grade II-IV acute GVHD after HAPLO was higher than after SIB (33% vs. 18%; P = .003), and was comparable to the rate with MUD (30%). The rates of grade III-IV acute GVHD were similar for all three cohorts (HAPLO, 9%; SIB, 6%; and MUD, 9%).

At 1 year, the cumulative rate of chronic GVHD was 26% after HAPLO and 25% after SIB; it was significantly higher at 41% after MUD (P = .017).

The cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality at 1 year was 17% with HAPLO, 13% with SIB, and significantly higher at 21% with MUD (P = .003). At 2 years, the cumulative incidence of relapse or progression was 39%, 49%, and 32%, respectively. The difference was significantly higher for SIB than HAPLO (P = .047) and MUD (P = .001).

There were no significant differences in 2-year overall survival, but MUD transplant recipients had lower overall survival (62%; 95% CI, 56 to 68; P = .039) compared with SIB transplant recipients.

“Whether HAPLO transplantation is the first choice instead of MUD transplantation and whether it can eventually substitute SIB transplantation in specific subgroups of patients must be assessed within the context of a randomized prospective clinical trial,” wrote Dr. Martinez and colleagues.

Hodgkin lymphoma patients who received haploidentical (HAPLO) allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after a nonmyeloablative regimen and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide had outcomes similar to those of patients who had conventional transplants, in a retrospective analysis of 709 adult patients in the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation database.

In addition, patients who underwent HAPLO had a lower incidence of extensive chronic graft-versus host disease (cGVHD) compared with HLA-matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplantation and higher cGVHD-free/relapse-free survival compared with HLA-matched sibling donor (SIB) transplantation.

“Use of HAPLO donors may allow patients to proceed more rapidly to transplantation, avoiding the time needed to complete a formal MUD search and arrange for graft collection at a remote center,” wrote Carmen Martinez, MD, of the Institute of Hematology and Oncology, Hospital Clinic, Barcelona. The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. Conventional donors are unavailable for a significant proportion of Hodgkin lymphoma patients.

Recommendations from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation consider alloHCT to be the standard treatment option for eligible patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who have relapsed after undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation and SIB or MUD. For the retrospective study, outcomes were compared for 338 patients who had SIB transplants, 273 patients who had MUD transplants, and 98 patients who received HAPLO transplants after a nonmyeloablative regimen and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCy) as GVHD prophylaxis.

The rate of grade II-IV acute GVHD after HAPLO was higher than after SIB (33% vs. 18%; P = .003), and was comparable to the rate with MUD (30%). The rates of grade III-IV acute GVHD were similar for all three cohorts (HAPLO, 9%; SIB, 6%; and MUD, 9%).

At 1 year, the cumulative rate of chronic GVHD was 26% after HAPLO and 25% after SIB; it was significantly higher at 41% after MUD (P = .017).

The cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality at 1 year was 17% with HAPLO, 13% with SIB, and significantly higher at 21% with MUD (P = .003). At 2 years, the cumulative incidence of relapse or progression was 39%, 49%, and 32%, respectively. The difference was significantly higher for SIB than HAPLO (P = .047) and MUD (P = .001).

There were no significant differences in 2-year overall survival, but MUD transplant recipients had lower overall survival (62%; 95% CI, 56 to 68; P = .039) compared with SIB transplant recipients.

“Whether HAPLO transplantation is the first choice instead of MUD transplantation and whether it can eventually substitute SIB transplantation in specific subgroups of patients must be assessed within the context of a randomized prospective clinical trial,” wrote Dr. Martinez and colleagues.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Haploidentical allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after a nonmyeloablative regimen and posttransplantation cyclophosphamide resulted in outcomes similar to those seen with conventional transplantations in Hodgkin lymphoma patients.

Major finding: The 2-year overall survival was 67% for HAPLO, 71% for a transplant from an HLA-matched sibling donor, and 62% for a transplant from an HLA-matched unrelated donor.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 709 adult patients in the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation database.

Disclosures: No funding source was disclosed. Dr. Martinez has no disclosures and several of the coauthors report relationships with industry.

Louisiana Program Brings “Missing” Patients With HIV Back Into the Fold

Ever-improving HIV treatments mean more people are living with the virus under control. But what if they are not getting the treatment? The Louisiana Links program, operating in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Shreveport, demonstrates that it is possible to make sure that more people are aware of the support they could be getting—and give it to them.

Louisiana Links is funded through the Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund (SMAIF), which supports programs to improve HIV prevention, care, and treatment for racial and ethnic minorities. During the funding period, the program has successfully linked and reengaged 90% of 686 enrollees to HIV medical care. Of the clients who were already in care but had not achieved viral suppression, 2 of 3 had the virus under control and were virally suppressed as shown at their last laboratory testing results.

In the Louisiana Links program, Linkage to Care Coordinators are hired to use state health department surveillance data in “innovative ways” to locate, engage, and enroll people living with HIV. They not only find “missing” people, but also provide support. For instance, coordinators attend medical and social service appointments with clients to ensure that they can overcome barriers to care and navigate complex health care systems. They work closely with local health care providers to maximize the resources and supportive services available to each client to increase long-term retention. They also educate clients about HIV and the importance of staying in care and adhering to treatment.

Due the success of the program, the Louisiana Department of Health has expanded services with core HIV prevention and care funding from the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Ever-improving HIV treatments mean more people are living with the virus under control. But what if they are not getting the treatment? The Louisiana Links program, operating in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Shreveport, demonstrates that it is possible to make sure that more people are aware of the support they could be getting—and give it to them.

Louisiana Links is funded through the Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund (SMAIF), which supports programs to improve HIV prevention, care, and treatment for racial and ethnic minorities. During the funding period, the program has successfully linked and reengaged 90% of 686 enrollees to HIV medical care. Of the clients who were already in care but had not achieved viral suppression, 2 of 3 had the virus under control and were virally suppressed as shown at their last laboratory testing results.

In the Louisiana Links program, Linkage to Care Coordinators are hired to use state health department surveillance data in “innovative ways” to locate, engage, and enroll people living with HIV. They not only find “missing” people, but also provide support. For instance, coordinators attend medical and social service appointments with clients to ensure that they can overcome barriers to care and navigate complex health care systems. They work closely with local health care providers to maximize the resources and supportive services available to each client to increase long-term retention. They also educate clients about HIV and the importance of staying in care and adhering to treatment.

Due the success of the program, the Louisiana Department of Health has expanded services with core HIV prevention and care funding from the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Ever-improving HIV treatments mean more people are living with the virus under control. But what if they are not getting the treatment? The Louisiana Links program, operating in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Shreveport, demonstrates that it is possible to make sure that more people are aware of the support they could be getting—and give it to them.

Louisiana Links is funded through the Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund (SMAIF), which supports programs to improve HIV prevention, care, and treatment for racial and ethnic minorities. During the funding period, the program has successfully linked and reengaged 90% of 686 enrollees to HIV medical care. Of the clients who were already in care but had not achieved viral suppression, 2 of 3 had the virus under control and were virally suppressed as shown at their last laboratory testing results.

In the Louisiana Links program, Linkage to Care Coordinators are hired to use state health department surveillance data in “innovative ways” to locate, engage, and enroll people living with HIV. They not only find “missing” people, but also provide support. For instance, coordinators attend medical and social service appointments with clients to ensure that they can overcome barriers to care and navigate complex health care systems. They work closely with local health care providers to maximize the resources and supportive services available to each client to increase long-term retention. They also educate clients about HIV and the importance of staying in care and adhering to treatment.

Due the success of the program, the Louisiana Department of Health has expanded services with core HIV prevention and care funding from the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration.

FDA approves drug to treat relapsed FL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted accelerated approval to copanlisib (Aliqopa), an intravenous PI3K inhibitor developed by Bayer.

The drug is now approved to treat adults with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least 2 prior systemic therapies.

Copanlisib received accelerated approval from the FDA because it has not yet shown a clinical benefit in these patients.

The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows conditional approval of a drug that fills an unmet medical need for a serious condition.

Accelerated approval is based on a surrogate or intermediate endpoint—in this case, overall response rate—that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit.

Continued approval of copanlisib for the aforementioned indication may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

The FDA previously granted copanlisib priority review, fast track designation, and orphan drug designation.

According to Bayer, copanlisib is now available. The prescribing information is available for download here.

In addition, Bayer has created the Aliqopa™ Resource Connections (ARCTM) Program, which includes resources to help patients navigate the insurance process and identify sources of financial assistance.

The program offers free medication to patients who are uninsured or underinsured and meet the eligibility criteria. It includes a $0 co-pay program for covered patients.

Phase 2 results

The FDA’s approval of copanlisib is based on data from the phase 2 CHRONOS-1 trial. Data from this trial were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 and the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting.

The trial included 104 patients with FL who had relapsed after at least 2 prior systemic therapies.

The median duration of treatment with copanlisib was 22 weeks (range, 1-105). Thirty-three patients (32%) were still on treatment at last follow-up.

The overall response rate was 59%, with 14% of patients achieving a complete response. The median duration of response was 12.2 months (range, 0+ to 22.6).

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (in ≥25% of patients) were diarrhea (34% all grades, 5% ≥grade 3), reduced neutrophil count (30% all grades, 24% ≥grade 3), fatigue (30% all grades, 2% ≥grade 3), and fever (25% all grades, 4% ≥grade 3).

There were 6 deaths, and 3 of them were attributed to copanlisib. One patient died of lung infection, 1 died of respiratory failure, and 1 died of a thromboembolic event. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted accelerated approval to copanlisib (Aliqopa), an intravenous PI3K inhibitor developed by Bayer.

The drug is now approved to treat adults with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least 2 prior systemic therapies.

Copanlisib received accelerated approval from the FDA because it has not yet shown a clinical benefit in these patients.

The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows conditional approval of a drug that fills an unmet medical need for a serious condition.

Accelerated approval is based on a surrogate or intermediate endpoint—in this case, overall response rate—that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit.

Continued approval of copanlisib for the aforementioned indication may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

The FDA previously granted copanlisib priority review, fast track designation, and orphan drug designation.

According to Bayer, copanlisib is now available. The prescribing information is available for download here.

In addition, Bayer has created the Aliqopa™ Resource Connections (ARCTM) Program, which includes resources to help patients navigate the insurance process and identify sources of financial assistance.

The program offers free medication to patients who are uninsured or underinsured and meet the eligibility criteria. It includes a $0 co-pay program for covered patients.

Phase 2 results

The FDA’s approval of copanlisib is based on data from the phase 2 CHRONOS-1 trial. Data from this trial were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 and the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting.

The trial included 104 patients with FL who had relapsed after at least 2 prior systemic therapies.

The median duration of treatment with copanlisib was 22 weeks (range, 1-105). Thirty-three patients (32%) were still on treatment at last follow-up.

The overall response rate was 59%, with 14% of patients achieving a complete response. The median duration of response was 12.2 months (range, 0+ to 22.6).

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (in ≥25% of patients) were diarrhea (34% all grades, 5% ≥grade 3), reduced neutrophil count (30% all grades, 24% ≥grade 3), fatigue (30% all grades, 2% ≥grade 3), and fever (25% all grades, 4% ≥grade 3).

There were 6 deaths, and 3 of them were attributed to copanlisib. One patient died of lung infection, 1 died of respiratory failure, and 1 died of a thromboembolic event. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted accelerated approval to copanlisib (Aliqopa), an intravenous PI3K inhibitor developed by Bayer.

The drug is now approved to treat adults with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) who have received at least 2 prior systemic therapies.

Copanlisib received accelerated approval from the FDA because it has not yet shown a clinical benefit in these patients.

The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows conditional approval of a drug that fills an unmet medical need for a serious condition.

Accelerated approval is based on a surrogate or intermediate endpoint—in this case, overall response rate—that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit.

Continued approval of copanlisib for the aforementioned indication may be contingent upon verification of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

The FDA previously granted copanlisib priority review, fast track designation, and orphan drug designation.

According to Bayer, copanlisib is now available. The prescribing information is available for download here.

In addition, Bayer has created the Aliqopa™ Resource Connections (ARCTM) Program, which includes resources to help patients navigate the insurance process and identify sources of financial assistance.

The program offers free medication to patients who are uninsured or underinsured and meet the eligibility criteria. It includes a $0 co-pay program for covered patients.

Phase 2 results

The FDA’s approval of copanlisib is based on data from the phase 2 CHRONOS-1 trial. Data from this trial were presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 and the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting.

The trial included 104 patients with FL who had relapsed after at least 2 prior systemic therapies.

The median duration of treatment with copanlisib was 22 weeks (range, 1-105). Thirty-three patients (32%) were still on treatment at last follow-up.

The overall response rate was 59%, with 14% of patients achieving a complete response. The median duration of response was 12.2 months (range, 0+ to 22.6).

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (in ≥25% of patients) were diarrhea (34% all grades, 5% ≥grade 3), reduced neutrophil count (30% all grades, 24% ≥grade 3), fatigue (30% all grades, 2% ≥grade 3), and fever (25% all grades, 4% ≥grade 3).

There were 6 deaths, and 3 of them were attributed to copanlisib. One patient died of lung infection, 1 died of respiratory failure, and 1 died of a thromboembolic event. ![]()

Immune status linked to outcomes of CAR T-cell therapy

MAINZ/FRANKFURT, GERMANY—Outcomes of treatment with a third-generation chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy are associated with a patient’s immune status, according to a phase 1/2a trial.

The CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy produced a complete response (CR) in 6 of 15 patients with relapsed/refractory CD19-positive leukemia or lymphoma.

Though all responders eventually relapsed, 4 patients—including 2 with stable disease (SD) after treatment—responded to subsequent therapy and are still alive, 1 of them beyond 36 months.

An analysis of blood samples taken throughout the study revealed that a patient’s immune status was associated with treatment failure and overall survival.

Tanja Lövgren, PhD, of Uppsala University in Sweden, and her colleagues presented these findings at the Third CRI-CIMT-EATI-AACR International Cancer Immunotherapy Conference: Translating Science into Survival (abstract B156).

“CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy has yielded remarkable response rates for patients who have B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia,” Dr Lövgren said. “However, many patients relapse.”

“In addition, response rates are more variable for patients who have other CD19-positive B-cell malignancies, and many patients experience serious adverse events. We set out to investigate the safety and effectiveness of a third-generation CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy and to identify potential biomarkers of treatment outcome.”

Dr Lövgren and her colleagues studied 15 patients (ages 24-72) who had relapsed or refractory CD19-positive B-cell malignancies:

- Six patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), including 3 cases that were transformed from follicular lymphoma (FL)

- Four patients with pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)

- Two patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)

- Two patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- One patient with FL transformed from Burkitt lymphoma.

Eleven patients received preconditioning with cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (3 doses at 25 mg/m2).

All patients received CAR T cells at 1 x 108, 2 x 107, or 2 x 108 cells/m2. These were autologous, CD19-targeting CAR T cells with 3 intracellular signaling domains derived from CD3 zeta, CD28, and 4-1BB.

The researchers assessed tumor responses via bone marrow/blood analysis and/or radiology, depending on the type of malignancy. The team also collected blood samples before CAR T-cell infusion and at multiple times after infusion.

Efficacy and safety

Six patients achieved a CR to treatment—3 with DLBCL (1 transformed), 2 with ALL, and 1 with CLL. Two patients had SD—1 with MCL and 1 with CLL. The remaining patients progressed.

All patients with a CR eventually relapsed. The median duration of CR was 5 months (range, 3-24 months).

Four patients—2 complete responders and 2 with SD—responded well to subsequent therapy and are still alive with 27 to 36 months of follow-up. This includes 1 patient with DLBCL, 1 with MCL, and 2 with CLL.

Four patients had serious adverse events. Three had cytokine-release syndrome, and 2 had neurological toxicity.

All cases of cytokine-release syndrome resolved after treatment with corticosteroids/anti-IL6R therapy. The neurological toxicity resolved spontaneously.

Immune status

An analysis of the blood samples taken throughout the study showed that high levels of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) prior to treatment was associated with decreased overall survival. In addition, increased levels of MDSCs after treatment preceded treatment failure.

Furthermore, high plasma levels of immunosuppressive factors—such as PD-L1 and PD-L2—after treatment were associated with decreased overall survival.

High plasma levels of biomarkers of an immunostimulatory environment—including IL-12, DC-LAMP, TRAIL, and FasL—before the administration of CAR T-cell therapy was associated with increased overall survival.

“[A]n immunostimulatory environment was associated with improved overall survival, while immunosuppressive cells and factors were associated with treatment failure and decreased overall survival,” Dr Lövgren said.

“We are hoping to follow up this study with another clinical trial that will combine CAR T-cell therapy with chemotherapy known to decrease the number of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressive cells. We are also looking to further optimize the CAR T-cell therapy.”

Dr Lövgren said the main limitations of this study are that it only included 15 patients, the patients had several different malignancies, and some patients may have been too sick to respond to any treatment.

This study was supported by funds from AFA Insurance AB, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Lions Fund at Uppsala University Hospital, and the Swedish State Support for Clinical Research. Dr Lövgren declared no conflicts of interest. ![]()

MAINZ/FRANKFURT, GERMANY—Outcomes of treatment with a third-generation chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy are associated with a patient’s immune status, according to a phase 1/2a trial.

The CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy produced a complete response (CR) in 6 of 15 patients with relapsed/refractory CD19-positive leukemia or lymphoma.

Though all responders eventually relapsed, 4 patients—including 2 with stable disease (SD) after treatment—responded to subsequent therapy and are still alive, 1 of them beyond 36 months.

An analysis of blood samples taken throughout the study revealed that a patient’s immune status was associated with treatment failure and overall survival.

Tanja Lövgren, PhD, of Uppsala University in Sweden, and her colleagues presented these findings at the Third CRI-CIMT-EATI-AACR International Cancer Immunotherapy Conference: Translating Science into Survival (abstract B156).

“CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy has yielded remarkable response rates for patients who have B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia,” Dr Lövgren said. “However, many patients relapse.”

“In addition, response rates are more variable for patients who have other CD19-positive B-cell malignancies, and many patients experience serious adverse events. We set out to investigate the safety and effectiveness of a third-generation CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy and to identify potential biomarkers of treatment outcome.”

Dr Lövgren and her colleagues studied 15 patients (ages 24-72) who had relapsed or refractory CD19-positive B-cell malignancies:

- Six patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), including 3 cases that were transformed from follicular lymphoma (FL)

- Four patients with pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)

- Two patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)

- Two patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- One patient with FL transformed from Burkitt lymphoma.

Eleven patients received preconditioning with cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (3 doses at 25 mg/m2).

All patients received CAR T cells at 1 x 108, 2 x 107, or 2 x 108 cells/m2. These were autologous, CD19-targeting CAR T cells with 3 intracellular signaling domains derived from CD3 zeta, CD28, and 4-1BB.

The researchers assessed tumor responses via bone marrow/blood analysis and/or radiology, depending on the type of malignancy. The team also collected blood samples before CAR T-cell infusion and at multiple times after infusion.

Efficacy and safety

Six patients achieved a CR to treatment—3 with DLBCL (1 transformed), 2 with ALL, and 1 with CLL. Two patients had SD—1 with MCL and 1 with CLL. The remaining patients progressed.

All patients with a CR eventually relapsed. The median duration of CR was 5 months (range, 3-24 months).

Four patients—2 complete responders and 2 with SD—responded well to subsequent therapy and are still alive with 27 to 36 months of follow-up. This includes 1 patient with DLBCL, 1 with MCL, and 2 with CLL.

Four patients had serious adverse events. Three had cytokine-release syndrome, and 2 had neurological toxicity.

All cases of cytokine-release syndrome resolved after treatment with corticosteroids/anti-IL6R therapy. The neurological toxicity resolved spontaneously.

Immune status

An analysis of the blood samples taken throughout the study showed that high levels of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) prior to treatment was associated with decreased overall survival. In addition, increased levels of MDSCs after treatment preceded treatment failure.

Furthermore, high plasma levels of immunosuppressive factors—such as PD-L1 and PD-L2—after treatment were associated with decreased overall survival.

High plasma levels of biomarkers of an immunostimulatory environment—including IL-12, DC-LAMP, TRAIL, and FasL—before the administration of CAR T-cell therapy was associated with increased overall survival.

“[A]n immunostimulatory environment was associated with improved overall survival, while immunosuppressive cells and factors were associated with treatment failure and decreased overall survival,” Dr Lövgren said.

“We are hoping to follow up this study with another clinical trial that will combine CAR T-cell therapy with chemotherapy known to decrease the number of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressive cells. We are also looking to further optimize the CAR T-cell therapy.”

Dr Lövgren said the main limitations of this study are that it only included 15 patients, the patients had several different malignancies, and some patients may have been too sick to respond to any treatment.

This study was supported by funds from AFA Insurance AB, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Lions Fund at Uppsala University Hospital, and the Swedish State Support for Clinical Research. Dr Lövgren declared no conflicts of interest. ![]()

MAINZ/FRANKFURT, GERMANY—Outcomes of treatment with a third-generation chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy are associated with a patient’s immune status, according to a phase 1/2a trial.

The CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy produced a complete response (CR) in 6 of 15 patients with relapsed/refractory CD19-positive leukemia or lymphoma.

Though all responders eventually relapsed, 4 patients—including 2 with stable disease (SD) after treatment—responded to subsequent therapy and are still alive, 1 of them beyond 36 months.

An analysis of blood samples taken throughout the study revealed that a patient’s immune status was associated with treatment failure and overall survival.

Tanja Lövgren, PhD, of Uppsala University in Sweden, and her colleagues presented these findings at the Third CRI-CIMT-EATI-AACR International Cancer Immunotherapy Conference: Translating Science into Survival (abstract B156).

“CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy has yielded remarkable response rates for patients who have B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia,” Dr Lövgren said. “However, many patients relapse.”

“In addition, response rates are more variable for patients who have other CD19-positive B-cell malignancies, and many patients experience serious adverse events. We set out to investigate the safety and effectiveness of a third-generation CD19-specific CAR T-cell therapy and to identify potential biomarkers of treatment outcome.”

Dr Lövgren and her colleagues studied 15 patients (ages 24-72) who had relapsed or refractory CD19-positive B-cell malignancies:

- Six patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), including 3 cases that were transformed from follicular lymphoma (FL)

- Four patients with pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)

- Two patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)

- Two patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- One patient with FL transformed from Burkitt lymphoma.

Eleven patients received preconditioning with cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and fludarabine (3 doses at 25 mg/m2).

All patients received CAR T cells at 1 x 108, 2 x 107, or 2 x 108 cells/m2. These were autologous, CD19-targeting CAR T cells with 3 intracellular signaling domains derived from CD3 zeta, CD28, and 4-1BB.

The researchers assessed tumor responses via bone marrow/blood analysis and/or radiology, depending on the type of malignancy. The team also collected blood samples before CAR T-cell infusion and at multiple times after infusion.

Efficacy and safety

Six patients achieved a CR to treatment—3 with DLBCL (1 transformed), 2 with ALL, and 1 with CLL. Two patients had SD—1 with MCL and 1 with CLL. The remaining patients progressed.

All patients with a CR eventually relapsed. The median duration of CR was 5 months (range, 3-24 months).

Four patients—2 complete responders and 2 with SD—responded well to subsequent therapy and are still alive with 27 to 36 months of follow-up. This includes 1 patient with DLBCL, 1 with MCL, and 2 with CLL.

Four patients had serious adverse events. Three had cytokine-release syndrome, and 2 had neurological toxicity.

All cases of cytokine-release syndrome resolved after treatment with corticosteroids/anti-IL6R therapy. The neurological toxicity resolved spontaneously.

Immune status

An analysis of the blood samples taken throughout the study showed that high levels of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) prior to treatment was associated with decreased overall survival. In addition, increased levels of MDSCs after treatment preceded treatment failure.

Furthermore, high plasma levels of immunosuppressive factors—such as PD-L1 and PD-L2—after treatment were associated with decreased overall survival.

High plasma levels of biomarkers of an immunostimulatory environment—including IL-12, DC-LAMP, TRAIL, and FasL—before the administration of CAR T-cell therapy was associated with increased overall survival.

“[A]n immunostimulatory environment was associated with improved overall survival, while immunosuppressive cells and factors were associated with treatment failure and decreased overall survival,” Dr Lövgren said.

“We are hoping to follow up this study with another clinical trial that will combine CAR T-cell therapy with chemotherapy known to decrease the number of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressive cells. We are also looking to further optimize the CAR T-cell therapy.”

Dr Lövgren said the main limitations of this study are that it only included 15 patients, the patients had several different malignancies, and some patients may have been too sick to respond to any treatment.

This study was supported by funds from AFA Insurance AB, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, the Lions Fund at Uppsala University Hospital, and the Swedish State Support for Clinical Research. Dr Lövgren declared no conflicts of interest. ![]()

Survey reveals lack of specialized care for AYAs with cancer

MADRID—New research indicates there is a lack of specialized care in Europe for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer.

In a survey of more than 200 European healthcare professionals, more than two-thirds of respondents said they did not have access to specialized services where adult and pediatric cancer specialists work together to plan treatment and deliver care to AYAs with cancer.

This lack of services was more pronounced in Eastern and Southern Europe than Western and Northern Europe.

“The survey found gaps and disparities in cancer care for adolescents and young adults across Europe,” said study author Emmanouil Saloustros, MD, a consultant medical oncologist at General Hospital of Heraklion “Venizelio” in Heraklion, Crete, Greece.

Dr Saloustros and his colleagues presented these findings at the ESMO 2017 Congress (abstract 1438O_PR) and reported them in ESMO Open.

The researchers sent an online survey on the status of care and research in AYAs (ages 15-39) to members of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the European Society for Paediatric Oncology (SIOPE).

The team received responses from 266 healthcare professionals across Europe—55% of them female. Eleven percent were age 20–29, 29% were age 30–39, 26% were age 40–49, 25% were age 50–59, and 9% were age 60 and older.

Forty-eight percent were medical oncologists, 21% were pediatric oncologists, 8% were in training, 5% were hematologists, 4% were radiation oncologists, and 2% were surgical oncologists. The rest were other types of healthcare professionals, such as oncology nurses.

Fifty-two percent of respondents worked in general academic centers, 19% in specialized cancer hospitals, and 11% in pediatric hospitals. Sixty percent of respondents had been trained to treat adults with cancer, 25% to treat pediatric cancer patients, and 15% were trained to treat both.