User login

Medical-level empathy? Yup, ChatGPT can fake that

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

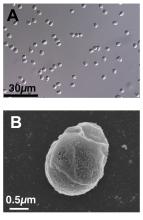

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

Caution: Robotic uprisings in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear

ChatGPT. If you’ve been even in the proximity of the Internet lately, you may have heard of it. It’s quite an incredible piece of technology, an artificial intelligence that really could up-end a lot of industries. And lest doctors believe they’re safe from robotic replacement, consider this: ChatGPT took a test commonly used as a study resource by ophthalmologists and scored a 46%. Obviously, that’s not a passing grade. Job safe, right?

A month later, the researchers tried again. This time, ChatGPT got a 58%. Still not passing, and ChatGPT did especially poorly on ophthalmology specialty questions (it got 80% of general medicine questions right), but still, the jump in quality after just a month is ... concerning. It’s not like an AI will forget things. That score can only go up, and it’ll go up faster than you think.

“Sure, the robot is smart,” the doctors out there are thinking, “but how can an AI compete with human compassion, understanding, and bedside manner?”

And they’d be right. When it comes to bedside manner, there’s no competition between man and bot. ChatGPT is already winning.

In another study, researchers sampled nearly 200 questions from the subreddit r/AskDocs, which received verified physician responses. The researchers fed ChatGPT the questions – without the doctor’s answer – and a panel of health care professionals evaluated both the human doctor and ChatGPT in terms of quality and empathy.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the robot did better when it came to quality, providing a high-quality response 79% of the time, versus 22% for the human. But empathy? It was a bloodbath. ChatGPT provided an empathetic or very empathetic response 45% of the time, while humans could only do so 4.6% of the time. So much for bedside manner.

The researchers were suspiciously quick to note that ChatGPT isn’t a legitimate replacement for physicians, but could represent a tool to better provide care for patients. But let’s be honest, given ChatGPT’s quick advancement, how long before some intrepid stockholder says: “Hey, instead of paying doctors, why don’t we just use the free robot instead?” We give it a week. Or 11 minutes.

This week, on ‘As the sperm turns’

We’ve got a lot of spermy ground to cover, so let’s get right to it, starting with the small and working our way up.

We’re all pretty familiar with the basic structure of a sperm cell, yes? Bulbous head that contains all the important genetic information and a tail-like flagellum to propel it to its ultimate destination. Not much to work with there, you’d think, but what if Mother Nature, who clearly has a robust sense of humor, had something else in mind?

We present exhibit A, Paramormyorps kingsleyae, also known as the electric elephantfish, which happens to be the only known vertebrate species with tailless sperm. Sounds crazy to us, too, but Jason Gallant, PhD, of

Michigan State University, Lansing, has a theory: “A general notion in biology is that sperm are cheap, and eggs are expensive – but these fish may be telling us that sperm are more expensive than we might think. They could be saving energy by cutting back on sperm tails.”

He and his team think that finding the gene that turns off development of the flagellum in the elephant fish could benefit humans, specifically those with a genetic disorder called primary ciliary dyskinesia, whose lack of normally functioning cilia and flagella leads to chronic respiratory infection, abnormally positioned organs, fluid on the brain, and infertility.

And that – with “that” being infertility – brings us to exhibit B, a 41-year-old Dutch man named Jonathan Meijer who clearly has too much time on his hands.

A court in the Netherlands recently ordered him, and not for the first time, to stop donating sperm to fertility clinics after it was discovered that he had fathered between 500 and 600 children around the world. He had been banned from donating to Dutch clinics in 2017, at which point he had already fathered 100 children, but managed a workaround by donating internationally and online, sometimes using another name.

The judge ordered Mr. Meijer to contact all of the clinics abroad and ask them to destroy any of his sperm they still had in stock and threatened to fine him over $100,000 for each future violation.

Okay, so here’s the thing. We have been, um, let’s call it ... warned, about the evils of tastelessness in journalism, so we’re going to do what Mr. Meijer should have done and abstain. And we can last for longer than 11 minutes.

The realm of lost luggage and lost sleep

It may be convenient to live near an airport if you’re a frequent flyer, but it really doesn’t help your sleep numbers.

The first look at how such a common sound affects sleep duration showed that people exposed to even 45 decibels of airplane noise were less likely to get the 7-9 hours of sleep needed for healthy functioning, investigators said in Environmental Health Perspectives.

How loud is 45 dB exactly? A normal conversation is about 50 dB, while a whisper is 30 dB, to give you an idea. Airplane noise at 45 dB? You might not even notice it amongst the other noises in daily life.

The researchers looked at data from about 35,000 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study who live around 90 major U.S. airports. They examined plane noise every 5 years between 1995 and 2005, focusing on estimates of nighttime and daytime levels. Short sleep was most common among the nurses who lived on the West Coast, near major cargo airports or large bodies of water, and also among those who reported no hearing loss.

The investigators noted, however, that there was no consistent association between airplane noise and quality of sleep and stopped short of making any policy recommendations. Still, sleep is a very important, yet slept-on (pun intended) factor for our overall health, so it’s good to know if anything has the potential to cause disruption.

Gray hair and aging: Could ‘stuck’ stem cells be to blame?

New evidence points more to a cycle wherein undifferentiated stem cells mature to perform their hair-coloring duties and then transform back to their primitive form. To accomplish this, they need to stay on the move.

When these special stem cells get “stuck” in the follicle, gray hair is the result, according to a new study reported online in Nature.

The regeneration cycle of melanocyte stem cells (McSCs) to melanocytes and back again can last for years. However, McSCs die sooner than do other cells nearby, such as hair follicle stem cells. This difference can explain why people go gray but still grow hair.

“It was thought that melanocyte stem cells are maintained in an undifferentiated state, instead of repeating differentiation and de-differentiation,” said the study’s senior investigator Mayumi Ito, PhD, professor in the departments of dermatology and cell biology at NYU Langone Health, New York.

The process involves different compartments in the hair follicle – the germ area is where the stem cells regenerate; the follicle bulge is where they get stuck. A different microenvironment in each location dictates how they change. This “chameleon-like” property surprised researchers.

Now that investigators figured out how gray hair might get started, a next step will be to search for a way to stop it.

The research has been performed in mice to date but could translate to humans. “Because the structure of the hair follicle is similar between mice and humans, we speculate that human melanocytes may also demonstrate the plasticity during hair regeneration,” Dr. Ito told this news organization.

Future findings could also lead to new therapies. “Our study suggests that moving melanocytes to a proper location within the hair follicle may help prevent gray hair,” Dr. Ito said.

Given the known effects of ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation on melanocytes, Dr. Ito and colleagues wanted to see what effect it might have on this cycle. So in the study, they exposed hair follicles of mice to UVB radiation and report it speeds up the process for McSCs to transform to color-producing melanocytes. They found that these McSCs can regenerate or change back to undifferentiated stem cells, so UVB radiation does not interrupt the process.

A melanoma clue?

The study also could have implications for melanoma. Unlike other tumors, melanocytes that cause cancer can self-renew even from a fully differentiated, pigmented form, the researchers note.

This makes melanomas more difficult to eliminate.

“Our study suggests normal melanocytes are very plastic and can reverse a differentiation state. Melanoma cells are known to be very plastic,” Dr. Ito said. “We consider this feature of melanoma may be related to the high plasticity of original melanocytes.”

The finding that melanocyte stem cells “are more plastic than maybe previously given credit for … certainly has implications in melanoma,” agreed Melissa Harris, PhD, associate professor, department of biology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, when asked to comment on the study.

Small technology, big insights?

The advanced technology used by Dr. Ito and colleagues in the study included 3D-intravital imaging and single-cell RNA sequencing to track the stem cells in almost real time as they aged and moved within each hair follicle.

“This paper uses a nice mix of classic and modern techniques to help answer a question that many in the field of pigmentation biology have suspected for a long time. Not all dormant melanocyte stem cells are created equal,” Dr. Harris said.

“The one question not answered in this paper is how to reverse the dysfunction of the melanocyte stem cell ‘stuck’ in the hair bulge,” Dr. Harris added. “There are numerous clinical case studies in humans showing medicine-induced hair repigmentation, and perhaps these cases are examples of dysfunctional melanocyte stem cells becoming ‘unstuck.’ ”

‘Very interesting’ findings

The study and its results “are very interesting from a mechanistic perspective and basic science view,” said Anthony M. Rossi, MD, a private practice dermatologist and assistant attending dermatologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, when asked to comment on the results.

The research provides another view of how melanocyte stem cells can pigment the hair shaft, Dr. Rossi added. “It gives insight into the behavior of stem cells and how they can travel and change state, something not well-known before.”

Dr. Rossi cautioned that other mechanisms are likely taking place. He pointed out that graying of hair can actually occur after a sudden stress event, as well as with vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, vitiligo-related autoimmune destruction, neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, and alopecia areata.

The “standout concept” in this paper is that the melanocyte stem cells are stranded and are not getting the right signal from the microenvironment to amplify and appropriately migrate to provide pigment to the hair shaft, said Paradi Mirmirani, MD, a private practice dermatologist in Vallejo, Calif.

It could be challenging to find the right signaling to reverse the graying process, Dr. Mirmirani added. “But the first step is always to understand the underlying basic mechanism. It would be interesting to see if other factors such as smoking, stress … influence the melanocyte stem cells in the same way.”

Grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense supported the study. Dr. Ito, Dr. Harris, Dr. Mirmirani, and Dr. Rossi had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New evidence points more to a cycle wherein undifferentiated stem cells mature to perform their hair-coloring duties and then transform back to their primitive form. To accomplish this, they need to stay on the move.

When these special stem cells get “stuck” in the follicle, gray hair is the result, according to a new study reported online in Nature.

The regeneration cycle of melanocyte stem cells (McSCs) to melanocytes and back again can last for years. However, McSCs die sooner than do other cells nearby, such as hair follicle stem cells. This difference can explain why people go gray but still grow hair.

“It was thought that melanocyte stem cells are maintained in an undifferentiated state, instead of repeating differentiation and de-differentiation,” said the study’s senior investigator Mayumi Ito, PhD, professor in the departments of dermatology and cell biology at NYU Langone Health, New York.

The process involves different compartments in the hair follicle – the germ area is where the stem cells regenerate; the follicle bulge is where they get stuck. A different microenvironment in each location dictates how they change. This “chameleon-like” property surprised researchers.

Now that investigators figured out how gray hair might get started, a next step will be to search for a way to stop it.

The research has been performed in mice to date but could translate to humans. “Because the structure of the hair follicle is similar between mice and humans, we speculate that human melanocytes may also demonstrate the plasticity during hair regeneration,” Dr. Ito told this news organization.

Future findings could also lead to new therapies. “Our study suggests that moving melanocytes to a proper location within the hair follicle may help prevent gray hair,” Dr. Ito said.

Given the known effects of ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation on melanocytes, Dr. Ito and colleagues wanted to see what effect it might have on this cycle. So in the study, they exposed hair follicles of mice to UVB radiation and report it speeds up the process for McSCs to transform to color-producing melanocytes. They found that these McSCs can regenerate or change back to undifferentiated stem cells, so UVB radiation does not interrupt the process.

A melanoma clue?

The study also could have implications for melanoma. Unlike other tumors, melanocytes that cause cancer can self-renew even from a fully differentiated, pigmented form, the researchers note.

This makes melanomas more difficult to eliminate.

“Our study suggests normal melanocytes are very plastic and can reverse a differentiation state. Melanoma cells are known to be very plastic,” Dr. Ito said. “We consider this feature of melanoma may be related to the high plasticity of original melanocytes.”

The finding that melanocyte stem cells “are more plastic than maybe previously given credit for … certainly has implications in melanoma,” agreed Melissa Harris, PhD, associate professor, department of biology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, when asked to comment on the study.

Small technology, big insights?

The advanced technology used by Dr. Ito and colleagues in the study included 3D-intravital imaging and single-cell RNA sequencing to track the stem cells in almost real time as they aged and moved within each hair follicle.

“This paper uses a nice mix of classic and modern techniques to help answer a question that many in the field of pigmentation biology have suspected for a long time. Not all dormant melanocyte stem cells are created equal,” Dr. Harris said.

“The one question not answered in this paper is how to reverse the dysfunction of the melanocyte stem cell ‘stuck’ in the hair bulge,” Dr. Harris added. “There are numerous clinical case studies in humans showing medicine-induced hair repigmentation, and perhaps these cases are examples of dysfunctional melanocyte stem cells becoming ‘unstuck.’ ”

‘Very interesting’ findings

The study and its results “are very interesting from a mechanistic perspective and basic science view,” said Anthony M. Rossi, MD, a private practice dermatologist and assistant attending dermatologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, when asked to comment on the results.

The research provides another view of how melanocyte stem cells can pigment the hair shaft, Dr. Rossi added. “It gives insight into the behavior of stem cells and how they can travel and change state, something not well-known before.”

Dr. Rossi cautioned that other mechanisms are likely taking place. He pointed out that graying of hair can actually occur after a sudden stress event, as well as with vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, vitiligo-related autoimmune destruction, neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, and alopecia areata.

The “standout concept” in this paper is that the melanocyte stem cells are stranded and are not getting the right signal from the microenvironment to amplify and appropriately migrate to provide pigment to the hair shaft, said Paradi Mirmirani, MD, a private practice dermatologist in Vallejo, Calif.

It could be challenging to find the right signaling to reverse the graying process, Dr. Mirmirani added. “But the first step is always to understand the underlying basic mechanism. It would be interesting to see if other factors such as smoking, stress … influence the melanocyte stem cells in the same way.”

Grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense supported the study. Dr. Ito, Dr. Harris, Dr. Mirmirani, and Dr. Rossi had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New evidence points more to a cycle wherein undifferentiated stem cells mature to perform their hair-coloring duties and then transform back to their primitive form. To accomplish this, they need to stay on the move.

When these special stem cells get “stuck” in the follicle, gray hair is the result, according to a new study reported online in Nature.

The regeneration cycle of melanocyte stem cells (McSCs) to melanocytes and back again can last for years. However, McSCs die sooner than do other cells nearby, such as hair follicle stem cells. This difference can explain why people go gray but still grow hair.

“It was thought that melanocyte stem cells are maintained in an undifferentiated state, instead of repeating differentiation and de-differentiation,” said the study’s senior investigator Mayumi Ito, PhD, professor in the departments of dermatology and cell biology at NYU Langone Health, New York.

The process involves different compartments in the hair follicle – the germ area is where the stem cells regenerate; the follicle bulge is where they get stuck. A different microenvironment in each location dictates how they change. This “chameleon-like” property surprised researchers.

Now that investigators figured out how gray hair might get started, a next step will be to search for a way to stop it.

The research has been performed in mice to date but could translate to humans. “Because the structure of the hair follicle is similar between mice and humans, we speculate that human melanocytes may also demonstrate the plasticity during hair regeneration,” Dr. Ito told this news organization.

Future findings could also lead to new therapies. “Our study suggests that moving melanocytes to a proper location within the hair follicle may help prevent gray hair,” Dr. Ito said.

Given the known effects of ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation on melanocytes, Dr. Ito and colleagues wanted to see what effect it might have on this cycle. So in the study, they exposed hair follicles of mice to UVB radiation and report it speeds up the process for McSCs to transform to color-producing melanocytes. They found that these McSCs can regenerate or change back to undifferentiated stem cells, so UVB radiation does not interrupt the process.

A melanoma clue?

The study also could have implications for melanoma. Unlike other tumors, melanocytes that cause cancer can self-renew even from a fully differentiated, pigmented form, the researchers note.

This makes melanomas more difficult to eliminate.

“Our study suggests normal melanocytes are very plastic and can reverse a differentiation state. Melanoma cells are known to be very plastic,” Dr. Ito said. “We consider this feature of melanoma may be related to the high plasticity of original melanocytes.”

The finding that melanocyte stem cells “are more plastic than maybe previously given credit for … certainly has implications in melanoma,” agreed Melissa Harris, PhD, associate professor, department of biology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, when asked to comment on the study.

Small technology, big insights?

The advanced technology used by Dr. Ito and colleagues in the study included 3D-intravital imaging and single-cell RNA sequencing to track the stem cells in almost real time as they aged and moved within each hair follicle.

“This paper uses a nice mix of classic and modern techniques to help answer a question that many in the field of pigmentation biology have suspected for a long time. Not all dormant melanocyte stem cells are created equal,” Dr. Harris said.

“The one question not answered in this paper is how to reverse the dysfunction of the melanocyte stem cell ‘stuck’ in the hair bulge,” Dr. Harris added. “There are numerous clinical case studies in humans showing medicine-induced hair repigmentation, and perhaps these cases are examples of dysfunctional melanocyte stem cells becoming ‘unstuck.’ ”

‘Very interesting’ findings

The study and its results “are very interesting from a mechanistic perspective and basic science view,” said Anthony M. Rossi, MD, a private practice dermatologist and assistant attending dermatologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, when asked to comment on the results.

The research provides another view of how melanocyte stem cells can pigment the hair shaft, Dr. Rossi added. “It gives insight into the behavior of stem cells and how they can travel and change state, something not well-known before.”

Dr. Rossi cautioned that other mechanisms are likely taking place. He pointed out that graying of hair can actually occur after a sudden stress event, as well as with vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, vitiligo-related autoimmune destruction, neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, and alopecia areata.

The “standout concept” in this paper is that the melanocyte stem cells are stranded and are not getting the right signal from the microenvironment to amplify and appropriately migrate to provide pigment to the hair shaft, said Paradi Mirmirani, MD, a private practice dermatologist in Vallejo, Calif.

It could be challenging to find the right signaling to reverse the graying process, Dr. Mirmirani added. “But the first step is always to understand the underlying basic mechanism. It would be interesting to see if other factors such as smoking, stress … influence the melanocyte stem cells in the same way.”

Grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense supported the study. Dr. Ito, Dr. Harris, Dr. Mirmirani, and Dr. Rossi had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE

FDA fast tracks potential CAR T-cell therapy for lupus

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Fast Track designation for Cabaletta Bio’s cell therapy CABA-201 for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and lupus nephritis (LN), the company announced May 1.

The FDA cleared Cabaletta to begin a phase 1/2 clinical trial of CABA-201, the statement says, which will be the first trial accessing Cabaletta’s Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cells for Autoimmunity (CARTA) approach. CABA-201, a 4-1BB–containing fully human CD19-CAR T-cell investigational therapy, is designed to target and deplete CD19-positive B cells, “enabling an ‘immune system reset’ with durable remission in patients with SLE,” according to the press release. This news organization previously reported on a small study in Germany, published in Nature Medicine, that also used anti-CD19 CAR T cells to treat five patients with SLE.

This upcoming open-label study will enroll two cohorts containing six patients each. One cohort will be patients with SLE and active LN, and the other will be patients with SLE without renal involvement. The therapy is designed as a one-time infusion and will be administered at a dose of 1.0 x 106 cells/kg.

“We believe the FDA’s decision to grant Fast Track Designation for CABA-201 underscores the unmet need for a treatment that has the potential to provide deep and durable responses for people living with lupus and potentially other autoimmune diseases where B cells contribute to disease,” David J. Chang, MD, chief medical officer of Cabaletta, said in the press release.

FDA Fast Track is a process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs and other therapeutics that treat serious conditions and address unmet medical needs. Companies that receive Fast Track designation for a drug have the opportunity for more frequent meetings and written communication with the FDA about the drug’s development plan and design of clinical trials. The fast-tracked drug can also be eligible for accelerated approval and priority review if relevant criteria are met.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Fast Track designation for Cabaletta Bio’s cell therapy CABA-201 for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and lupus nephritis (LN), the company announced May 1.

The FDA cleared Cabaletta to begin a phase 1/2 clinical trial of CABA-201, the statement says, which will be the first trial accessing Cabaletta’s Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cells for Autoimmunity (CARTA) approach. CABA-201, a 4-1BB–containing fully human CD19-CAR T-cell investigational therapy, is designed to target and deplete CD19-positive B cells, “enabling an ‘immune system reset’ with durable remission in patients with SLE,” according to the press release. This news organization previously reported on a small study in Germany, published in Nature Medicine, that also used anti-CD19 CAR T cells to treat five patients with SLE.

This upcoming open-label study will enroll two cohorts containing six patients each. One cohort will be patients with SLE and active LN, and the other will be patients with SLE without renal involvement. The therapy is designed as a one-time infusion and will be administered at a dose of 1.0 x 106 cells/kg.

“We believe the FDA’s decision to grant Fast Track Designation for CABA-201 underscores the unmet need for a treatment that has the potential to provide deep and durable responses for people living with lupus and potentially other autoimmune diseases where B cells contribute to disease,” David J. Chang, MD, chief medical officer of Cabaletta, said in the press release.

FDA Fast Track is a process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs and other therapeutics that treat serious conditions and address unmet medical needs. Companies that receive Fast Track designation for a drug have the opportunity for more frequent meetings and written communication with the FDA about the drug’s development plan and design of clinical trials. The fast-tracked drug can also be eligible for accelerated approval and priority review if relevant criteria are met.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Fast Track designation for Cabaletta Bio’s cell therapy CABA-201 for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and lupus nephritis (LN), the company announced May 1.

The FDA cleared Cabaletta to begin a phase 1/2 clinical trial of CABA-201, the statement says, which will be the first trial accessing Cabaletta’s Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cells for Autoimmunity (CARTA) approach. CABA-201, a 4-1BB–containing fully human CD19-CAR T-cell investigational therapy, is designed to target and deplete CD19-positive B cells, “enabling an ‘immune system reset’ with durable remission in patients with SLE,” according to the press release. This news organization previously reported on a small study in Germany, published in Nature Medicine, that also used anti-CD19 CAR T cells to treat five patients with SLE.

This upcoming open-label study will enroll two cohorts containing six patients each. One cohort will be patients with SLE and active LN, and the other will be patients with SLE without renal involvement. The therapy is designed as a one-time infusion and will be administered at a dose of 1.0 x 106 cells/kg.

“We believe the FDA’s decision to grant Fast Track Designation for CABA-201 underscores the unmet need for a treatment that has the potential to provide deep and durable responses for people living with lupus and potentially other autoimmune diseases where B cells contribute to disease,” David J. Chang, MD, chief medical officer of Cabaletta, said in the press release.

FDA Fast Track is a process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs and other therapeutics that treat serious conditions and address unmet medical needs. Companies that receive Fast Track designation for a drug have the opportunity for more frequent meetings and written communication with the FDA about the drug’s development plan and design of clinical trials. The fast-tracked drug can also be eligible for accelerated approval and priority review if relevant criteria are met.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves first RSV vaccine for older adults

Arexvy, manufactured by GSK, is the world’s first RSV vaccine for adults aged 60 years and older,the company said in an announcement.

Every year, RSV is responsible for 60,000–120,000 hospitalizations and 6,000–10,000 deaths among U.S. adults older than age, according to the FDA. Older adults with underlying health conditions — such as diabetes, a weakened immune system, or lung or heart disease — are at high risk for severe disease. "Today’s approval of the first RSV vaccine is an important public health achievement to prevent a disease which can be life-threatening and reflects the FDA’s continued commitment to facilitating the development of safe and effective vaccines for use in the United States," said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement.

The FDA approval of Arexvy was based on a clinical study of approximately 25,000 patients. Half of these patients received Arexvy, while the other half received a placebo. Researchers found that the RSV vaccine reduced RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) by nearly 83% and reduced the risk of developing severe RSV-associated LRTD by 94%. The most commonly reported side effects were injection site pain, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and joint stiffness/pain. Ten patients who received Arexvy and four patients who received placebo experienced atrial fibrillation within 30 days of vaccination. The company is planning to assess risk for atrial fibrillation in postmarking studies, the FDA said. The European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Arexvy on April 25, 2023, on the basis of data from the same clinical trial.

GSK said that the U.S. launch of Arexvy will occur sometime in the fall before the 2023/2024 RSV season, but the company did not provide exact dates. "Today marks a turning point in our effort to reduce the significant burden of RSV," said GSK’s chief scientific officer, Tony Wood, PhD, in a company statement. "Our focus now is to ensure eligible older adults in the U.S. can access the vaccine as quickly as possible and to progress regulatory review in other countries."

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Arexvy, manufactured by GSK, is the world’s first RSV vaccine for adults aged 60 years and older,the company said in an announcement.

Every year, RSV is responsible for 60,000–120,000 hospitalizations and 6,000–10,000 deaths among U.S. adults older than age, according to the FDA. Older adults with underlying health conditions — such as diabetes, a weakened immune system, or lung or heart disease — are at high risk for severe disease. "Today’s approval of the first RSV vaccine is an important public health achievement to prevent a disease which can be life-threatening and reflects the FDA’s continued commitment to facilitating the development of safe and effective vaccines for use in the United States," said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement.

The FDA approval of Arexvy was based on a clinical study of approximately 25,000 patients. Half of these patients received Arexvy, while the other half received a placebo. Researchers found that the RSV vaccine reduced RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) by nearly 83% and reduced the risk of developing severe RSV-associated LRTD by 94%. The most commonly reported side effects were injection site pain, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and joint stiffness/pain. Ten patients who received Arexvy and four patients who received placebo experienced atrial fibrillation within 30 days of vaccination. The company is planning to assess risk for atrial fibrillation in postmarking studies, the FDA said. The European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Arexvy on April 25, 2023, on the basis of data from the same clinical trial.

GSK said that the U.S. launch of Arexvy will occur sometime in the fall before the 2023/2024 RSV season, but the company did not provide exact dates. "Today marks a turning point in our effort to reduce the significant burden of RSV," said GSK’s chief scientific officer, Tony Wood, PhD, in a company statement. "Our focus now is to ensure eligible older adults in the U.S. can access the vaccine as quickly as possible and to progress regulatory review in other countries."

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Arexvy, manufactured by GSK, is the world’s first RSV vaccine for adults aged 60 years and older,the company said in an announcement.

Every year, RSV is responsible for 60,000–120,000 hospitalizations and 6,000–10,000 deaths among U.S. adults older than age, according to the FDA. Older adults with underlying health conditions — such as diabetes, a weakened immune system, or lung or heart disease — are at high risk for severe disease. "Today’s approval of the first RSV vaccine is an important public health achievement to prevent a disease which can be life-threatening and reflects the FDA’s continued commitment to facilitating the development of safe and effective vaccines for use in the United States," said Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in a statement.

The FDA approval of Arexvy was based on a clinical study of approximately 25,000 patients. Half of these patients received Arexvy, while the other half received a placebo. Researchers found that the RSV vaccine reduced RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) by nearly 83% and reduced the risk of developing severe RSV-associated LRTD by 94%. The most commonly reported side effects were injection site pain, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, and joint stiffness/pain. Ten patients who received Arexvy and four patients who received placebo experienced atrial fibrillation within 30 days of vaccination. The company is planning to assess risk for atrial fibrillation in postmarking studies, the FDA said. The European Medicine Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended approval of Arexvy on April 25, 2023, on the basis of data from the same clinical trial.

GSK said that the U.S. launch of Arexvy will occur sometime in the fall before the 2023/2024 RSV season, but the company did not provide exact dates. "Today marks a turning point in our effort to reduce the significant burden of RSV," said GSK’s chief scientific officer, Tony Wood, PhD, in a company statement. "Our focus now is to ensure eligible older adults in the U.S. can access the vaccine as quickly as possible and to progress regulatory review in other countries."

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

May 2023 - ICYMI

Gastroenterology

January 2023

Yardeni D et al. Current Best Practice in Hepatitis B Management and Understanding Long-term Prospects for Cure. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jan;164(1):42-60.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.10.008. Epub 2022 Oct 12. PMID: 36243037; PMCID: PMC9772068.

Laine L et al. Vonoprazan Versus Lansoprazole for Healing and Maintenance of Healing of Erosive Esophagitis: A Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jan;164(1):61-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.09.041. Epub 2022 Oct 10. PMID: 36228734.

February 2023

Ufere NN et al. Promoting Prognostic Understanding and Health Equity for Patients With Advanced Liver Disease: Using “Best Case/Worst Case.” Gastroenterology. 2023 Feb;164(2):171-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.005. PMID: 36702571.

March 2023

Heath JK et al. Training Generations of Clinician Educators: Applying the Novel Clinician Educator Milestones to Faculty Development. Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar;164(3):325-8.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.003. Epub 2022 Dec 9. PMID: 36509156.

Singh S et al. AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalpractice@gastro.org. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Role of Biomarkers for the Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar;164(3):344-72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.007. PMID: 36822736.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

January 2023

Speicher LL and Francis D. Improving Employee Experience: Reducing Burnout, Decreasing Turnover and Building Well-being. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jan;21(1):11-4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.020. Epub 2022 Sep 22. PMID: 36155248; PMCID: PMC9547273.

Penagini R et al. Rapid Drink Challenge During High-resolution Manometry for Evaluation of Esophageal Emptying in Treated Achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jan;21(1):55-63. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.047. Epub 2022 Feb 28. PMID: 35240328.

February 2023

Zaki TA et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Survival. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Feb;21(2):497-506.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.035. Epub 2022 Jun 16. PMID: 35716905; PMCID: PMC9835097.

Brenner DM et al. Rare, Overlooked, or Underappreciated Causes of Recurrent Abdominal Pain: A Primer for Gastroenterologists. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Feb;21(2):264-79. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.022. Epub 2022 Sep 27. PMID: 36180010.

March 2023

Hanna M et al. Emerging Tests for Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;21(3):604-16. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.008. Epub 2022 Dec 17. PMID: 36539002; PMCID: PMC9974876.

Ormsby EL et al. Association of Standardized Radiology Reporting and Management of Abdominal CT and MRI With Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;21(3):644-52.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.047. Epub 2022 Apr 15. PMID: 35436626.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Mohapatra S et al. (Accepted/In press). Outcomes of Endoscopic Resection for Colorectal Polyps with High-Grade Dysplasia or Intramucosal Cancer. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.01.003.

Holzwanger EA et al. Improving Dysplasia Detection in Barrett’s Esophagus. Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;25(2):157-66. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.01.002.

Gastroenterology

January 2023

Yardeni D et al. Current Best Practice in Hepatitis B Management and Understanding Long-term Prospects for Cure. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jan;164(1):42-60.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.10.008. Epub 2022 Oct 12. PMID: 36243037; PMCID: PMC9772068.

Laine L et al. Vonoprazan Versus Lansoprazole for Healing and Maintenance of Healing of Erosive Esophagitis: A Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jan;164(1):61-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.09.041. Epub 2022 Oct 10. PMID: 36228734.

February 2023

Ufere NN et al. Promoting Prognostic Understanding and Health Equity for Patients With Advanced Liver Disease: Using “Best Case/Worst Case.” Gastroenterology. 2023 Feb;164(2):171-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.005. PMID: 36702571.

March 2023

Heath JK et al. Training Generations of Clinician Educators: Applying the Novel Clinician Educator Milestones to Faculty Development. Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar;164(3):325-8.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.003. Epub 2022 Dec 9. PMID: 36509156.

Singh S et al. AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalpractice@gastro.org. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Role of Biomarkers for the Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar;164(3):344-72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.007. PMID: 36822736.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

January 2023

Speicher LL and Francis D. Improving Employee Experience: Reducing Burnout, Decreasing Turnover and Building Well-being. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jan;21(1):11-4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.020. Epub 2022 Sep 22. PMID: 36155248; PMCID: PMC9547273.

Penagini R et al. Rapid Drink Challenge During High-resolution Manometry for Evaluation of Esophageal Emptying in Treated Achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jan;21(1):55-63. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.047. Epub 2022 Feb 28. PMID: 35240328.

February 2023

Zaki TA et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Survival. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Feb;21(2):497-506.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.035. Epub 2022 Jun 16. PMID: 35716905; PMCID: PMC9835097.

Brenner DM et al. Rare, Overlooked, or Underappreciated Causes of Recurrent Abdominal Pain: A Primer for Gastroenterologists. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Feb;21(2):264-79. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.022. Epub 2022 Sep 27. PMID: 36180010.

March 2023

Hanna M et al. Emerging Tests for Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;21(3):604-16. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.008. Epub 2022 Dec 17. PMID: 36539002; PMCID: PMC9974876.

Ormsby EL et al. Association of Standardized Radiology Reporting and Management of Abdominal CT and MRI With Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;21(3):644-52.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.047. Epub 2022 Apr 15. PMID: 35436626.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Mohapatra S et al. (Accepted/In press). Outcomes of Endoscopic Resection for Colorectal Polyps with High-Grade Dysplasia or Intramucosal Cancer. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.01.003.

Holzwanger EA et al. Improving Dysplasia Detection in Barrett’s Esophagus. Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;25(2):157-66. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.01.002.

Gastroenterology

January 2023

Yardeni D et al. Current Best Practice in Hepatitis B Management and Understanding Long-term Prospects for Cure. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jan;164(1):42-60.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.10.008. Epub 2022 Oct 12. PMID: 36243037; PMCID: PMC9772068.

Laine L et al. Vonoprazan Versus Lansoprazole for Healing and Maintenance of Healing of Erosive Esophagitis: A Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2023 Jan;164(1):61-71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.09.041. Epub 2022 Oct 10. PMID: 36228734.

February 2023

Ufere NN et al. Promoting Prognostic Understanding and Health Equity for Patients With Advanced Liver Disease: Using “Best Case/Worst Case.” Gastroenterology. 2023 Feb;164(2):171-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.005. PMID: 36702571.

March 2023

Heath JK et al. Training Generations of Clinician Educators: Applying the Novel Clinician Educator Milestones to Faculty Development. Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar;164(3):325-8.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.003. Epub 2022 Dec 9. PMID: 36509156.

Singh S et al. AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalpractice@gastro.org. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Role of Biomarkers for the Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar;164(3):344-72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.12.007. PMID: 36822736.

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology

January 2023

Speicher LL and Francis D. Improving Employee Experience: Reducing Burnout, Decreasing Turnover and Building Well-being. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jan;21(1):11-4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.020. Epub 2022 Sep 22. PMID: 36155248; PMCID: PMC9547273.

Penagini R et al. Rapid Drink Challenge During High-resolution Manometry for Evaluation of Esophageal Emptying in Treated Achalasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jan;21(1):55-63. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.02.047. Epub 2022 Feb 28. PMID: 35240328.

February 2023

Zaki TA et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Survival. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Feb;21(2):497-506.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.035. Epub 2022 Jun 16. PMID: 35716905; PMCID: PMC9835097.

Brenner DM et al. Rare, Overlooked, or Underappreciated Causes of Recurrent Abdominal Pain: A Primer for Gastroenterologists. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Feb;21(2):264-79. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.09.022. Epub 2022 Sep 27. PMID: 36180010.

March 2023

Hanna M et al. Emerging Tests for Noninvasive Colorectal Cancer Screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;21(3):604-16. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.008. Epub 2022 Dec 17. PMID: 36539002; PMCID: PMC9974876.

Ormsby EL et al. Association of Standardized Radiology Reporting and Management of Abdominal CT and MRI With Diagnosis of Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Mar;21(3):644-52.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.047. Epub 2022 Apr 15. PMID: 35436626.

Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Mohapatra S et al. (Accepted/In press). Outcomes of Endoscopic Resection for Colorectal Polyps with High-Grade Dysplasia or Intramucosal Cancer. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.01.003.

Holzwanger EA et al. Improving Dysplasia Detection in Barrett’s Esophagus. Techniques and Innovations in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;25(2):157-66. doi: 10.1016/j.tige.2023.01.002.

Best practices document outlines genitourinary applications of lasers and energy-based devices

PHOENIX –

“Even a cursory review of PubMed today yields over 100,000 results” on this topic, Macrene R. Alexiades, MD, PhD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Add to that radiofrequency and various diagnoses, the number of publications has skyrocketed, particularly over the last 10 years.”

What has been missing from this hot research topic all these years, she continued, is that no one has distilled this pile of data into a practical guide for office-based clinicians who use lasers and energy-based devices for genitourinary conditions – until now. Working with experts in gynecology and urogynecology, Dr. Alexiades spearheaded a 2-year-long effort to assemble a document on optimal protocols and best practices for genitourinary application of lasers and energy-based devices. The document, published soon after the ASLMS meeting in Lasers in Medicine and Surgery, includes a table that lists the current Food and Drug Administration approval status of devices in genitourinary applications, as well as individual sections dedicated to fractional lasers, radiofrequency (RF) devices, and high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology. It concludes with a section on the current status of clearances and future pathways.

“The work we did was exhaustive,” said Dr. Alexiades, who is also founder and director of Dermatology & Laser Surgery Center of New York. “We went through all the clinical trial data and compiled the parameters that, as a consensus, we agree are best practices for each technology for which we had rigorous published data.”

The document contains a brief background on the history of the devices used for genitourinary issues and it addresses core topics for each technology, such as conditions treated, contraindications, preoperative physical assessment and preparation, perioperative protocols, and postoperative care.

Contraindications to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices are numerous and include use of an intrauterine device, active urinary tract or genital infection, vaginal bleeding, current pregnancy, active or recent malignancy, having an electrical implant anywhere in the body, significant concurrent illness, and an anticoagulative or thromboembolic condition or taking anticoagulant medications 1 week prior to the procedure. Another condition to screen for is advanced prolapse, which was considered a contraindication in all clinical trials, she added. “It’s important that you’re able to do the speculum exam and stage the prolapse” so that a patient with this contraindication is not treated.

Dr. Alexiades shared the following highlights from the document’s section related to the use of fractional CO2 lasers:

Preoperative management. Schedule the treatment one week after the patient’s menstrual period. Patients should avoid blood thinners for 7 days and avoid intercourse the night before the procedure. Reschedule in the case of fever, chills, or vaginal bleeding or discharge.

Preoperative physical exam and testing. A normal speculum exam and a recent negative PAP smear are required. For those of child-bearing potential, a pregnancy test is warranted. Obtain written and verbal consent, including discussion of all treatment options, risks, and benefits. No topical or local anesthesia is necessary internally. “Externally, we sometimes apply topical lidocaine gel, but I have found that’s not necessary in most cases,” Dr. Alexiades said. “The treatment is so quick.”

Peri-operative management. In general, device settings are provided by the manufacturer. “For most of the studies that had successful outcomes and no adverse events, researchers adhered to the mild or moderate settings on the technology,” she said. Energy settings were between 15 and 30 watts, delivered at a laser fluence of about 250-300 mJ/cm2 with a spacing of microbeams 1 mm apart. Typically, three treatments are done at 1-month intervals and maintenance treatments are recommended at 6 and 12 months based on duration of the outcomes.

Vulvovaginal postoperative management. A 3-day recovery time is recommended with avoidance of intercourse during this period, because “re-epithelialization is usually complete in 3 days, so we want to give the opportunity for the lining to heal prior to introducing any friction, Dr. Alexiades said.” Rarely, spotting or discharge may occur and there should be no discomfort. “Any severe discomfort or burning may potentially signify infection and should prompt evaluation and possibly vaginal cultures. The patient can shower, but we recommend avoiding seated baths to decrease any introduction of infectious agents.”

Patients should be followed up monthly until three treatments are completed, and a maintenance treatment is considered appropriate between 6 and 12 months. “I do recommend doing a 1-month follow-up following the final treatment, unless it’s a patient who has already had a series of three treatments and is coming in for maintenance,” she said.

In a study from her own practice, Dr. Alexiades evaluated a series of three fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and vagina with a 1-year follow-up in postmenopausal patients. She used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to assess changes in vaginal elasticity, fluid volume, vaginal pH, epithelial integrity, and moisture. She and her colleagues discovered that there was improvement in every VHI category after treatment and during the follow-up interval up to 6 months.

“Between 6 and 12 months, we started to see a return a bit toward baseline on all of these parameters,” she said. “The serendipitous discovery that I made during the course of that study was that early intervention improves outcomes. I observed that the younger, most recently postmenopausal cohort seemed to attain normal or near normal VHI quicker than the more extended postmenopausal cohorts.”

In an editorial published in 2020, Dr. Alexiades reviewed the effects of fractional CO2 laser treatment of vulvar skin on vaginal pH and referred to a study she conducted that found that the mean baseline pH pretreatment was 6.32 in the cohort of postmenopausal patients, and was reduced after 3 treatments. “Postmenopausally, the normal acidic pH becomes alkaline,” she said. But she did not expect to see an additional reduction in pH following the treatment out to 6 months. “This indicates that, whatever the wound healing and other restorative effects of these devices are, they seem to continue out to 6 months, at which point it turns around and moves toward baseline [levels].”

Dr. Alexiades highlighted two published meta-analyses of studies related to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices. One included 59 studies of 3,609 women treated for vaginal rejuvenation using either radiofrequency or fractional ablative laser therapy. The studies reported improvements in symptoms of GSM/VVA and sexual function, high patient satisfaction, with minor adverse events, including treatment-associated vaginal swelling or vaginal discharge.

“Further research needs to be completed to determine which specific pathologies can be treated, if maintenance treatment is necessary, and long-term safety concerns,” the authors concluded.

In another review, researchers analyzed 64 studies related to vaginal laser therapy for GSM. Of these, 47 were before and after studies without a control group, 10 were controlled intervention studies, and 7 were observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Vaginal laser treatment “seems to improve scores on the visual analogue scale, Female Sexual Function Index, and the Vaginal Health Index over the short term,” the authors wrote. “Safety outcomes are underreported and short term. Further well-designed clinical trials with sham-laser control groups and evaluating objective variables are needed to provide the best evidence on efficacy.”

“Lasers and energy-based devices are now considered alternative therapeutic modalities for genitourinary conditions,” Dr. Alexiades concluded. “The shortcomings in the literature with respect to lasers and device treatments demonstrate the need for the consensus on best practices and protocols.”

During a separate presentation at the meeting, Michael Gold, MD, highlighted data from Grand View Research, a market research database, which estimated that the global women’s health and wellness market is valued at more than $31 billion globally and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 4.8% from 2022 to 2030.

“Sales of women’s health energy-based devices continue to grow as new technologies are developed,” said Dr. Gold, a Nashville, Tenn.–based dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon who is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. “Evolving societal norms have made discussions about feminine health issues acceptable. Suffering in silence is no longer necessary or advocated.”

Dr. Alexiades disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela Lasers, Lumenis, Allergan/AbbVie, InMode, and Endymed. She is also the founder and CEO of Macrene Actives. Dr. Gold disclosed that he is a consultant to and/or an investigator and a speaker for Joylux, InMode, and Alma Lasers.

PHOENIX –

“Even a cursory review of PubMed today yields over 100,000 results” on this topic, Macrene R. Alexiades, MD, PhD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Add to that radiofrequency and various diagnoses, the number of publications has skyrocketed, particularly over the last 10 years.”

What has been missing from this hot research topic all these years, she continued, is that no one has distilled this pile of data into a practical guide for office-based clinicians who use lasers and energy-based devices for genitourinary conditions – until now. Working with experts in gynecology and urogynecology, Dr. Alexiades spearheaded a 2-year-long effort to assemble a document on optimal protocols and best practices for genitourinary application of lasers and energy-based devices. The document, published soon after the ASLMS meeting in Lasers in Medicine and Surgery, includes a table that lists the current Food and Drug Administration approval status of devices in genitourinary applications, as well as individual sections dedicated to fractional lasers, radiofrequency (RF) devices, and high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology. It concludes with a section on the current status of clearances and future pathways.

“The work we did was exhaustive,” said Dr. Alexiades, who is also founder and director of Dermatology & Laser Surgery Center of New York. “We went through all the clinical trial data and compiled the parameters that, as a consensus, we agree are best practices for each technology for which we had rigorous published data.”

The document contains a brief background on the history of the devices used for genitourinary issues and it addresses core topics for each technology, such as conditions treated, contraindications, preoperative physical assessment and preparation, perioperative protocols, and postoperative care.

Contraindications to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices are numerous and include use of an intrauterine device, active urinary tract or genital infection, vaginal bleeding, current pregnancy, active or recent malignancy, having an electrical implant anywhere in the body, significant concurrent illness, and an anticoagulative or thromboembolic condition or taking anticoagulant medications 1 week prior to the procedure. Another condition to screen for is advanced prolapse, which was considered a contraindication in all clinical trials, she added. “It’s important that you’re able to do the speculum exam and stage the prolapse” so that a patient with this contraindication is not treated.

Dr. Alexiades shared the following highlights from the document’s section related to the use of fractional CO2 lasers:

Preoperative management. Schedule the treatment one week after the patient’s menstrual period. Patients should avoid blood thinners for 7 days and avoid intercourse the night before the procedure. Reschedule in the case of fever, chills, or vaginal bleeding or discharge.

Preoperative physical exam and testing. A normal speculum exam and a recent negative PAP smear are required. For those of child-bearing potential, a pregnancy test is warranted. Obtain written and verbal consent, including discussion of all treatment options, risks, and benefits. No topical or local anesthesia is necessary internally. “Externally, we sometimes apply topical lidocaine gel, but I have found that’s not necessary in most cases,” Dr. Alexiades said. “The treatment is so quick.”

Peri-operative management. In general, device settings are provided by the manufacturer. “For most of the studies that had successful outcomes and no adverse events, researchers adhered to the mild or moderate settings on the technology,” she said. Energy settings were between 15 and 30 watts, delivered at a laser fluence of about 250-300 mJ/cm2 with a spacing of microbeams 1 mm apart. Typically, three treatments are done at 1-month intervals and maintenance treatments are recommended at 6 and 12 months based on duration of the outcomes.

Vulvovaginal postoperative management. A 3-day recovery time is recommended with avoidance of intercourse during this period, because “re-epithelialization is usually complete in 3 days, so we want to give the opportunity for the lining to heal prior to introducing any friction, Dr. Alexiades said.” Rarely, spotting or discharge may occur and there should be no discomfort. “Any severe discomfort or burning may potentially signify infection and should prompt evaluation and possibly vaginal cultures. The patient can shower, but we recommend avoiding seated baths to decrease any introduction of infectious agents.”

Patients should be followed up monthly until three treatments are completed, and a maintenance treatment is considered appropriate between 6 and 12 months. “I do recommend doing a 1-month follow-up following the final treatment, unless it’s a patient who has already had a series of three treatments and is coming in for maintenance,” she said.

In a study from her own practice, Dr. Alexiades evaluated a series of three fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and vagina with a 1-year follow-up in postmenopausal patients. She used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to assess changes in vaginal elasticity, fluid volume, vaginal pH, epithelial integrity, and moisture. She and her colleagues discovered that there was improvement in every VHI category after treatment and during the follow-up interval up to 6 months.

“Between 6 and 12 months, we started to see a return a bit toward baseline on all of these parameters,” she said. “The serendipitous discovery that I made during the course of that study was that early intervention improves outcomes. I observed that the younger, most recently postmenopausal cohort seemed to attain normal or near normal VHI quicker than the more extended postmenopausal cohorts.”

In an editorial published in 2020, Dr. Alexiades reviewed the effects of fractional CO2 laser treatment of vulvar skin on vaginal pH and referred to a study she conducted that found that the mean baseline pH pretreatment was 6.32 in the cohort of postmenopausal patients, and was reduced after 3 treatments. “Postmenopausally, the normal acidic pH becomes alkaline,” she said. But she did not expect to see an additional reduction in pH following the treatment out to 6 months. “This indicates that, whatever the wound healing and other restorative effects of these devices are, they seem to continue out to 6 months, at which point it turns around and moves toward baseline [levels].”

Dr. Alexiades highlighted two published meta-analyses of studies related to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices. One included 59 studies of 3,609 women treated for vaginal rejuvenation using either radiofrequency or fractional ablative laser therapy. The studies reported improvements in symptoms of GSM/VVA and sexual function, high patient satisfaction, with minor adverse events, including treatment-associated vaginal swelling or vaginal discharge.

“Further research needs to be completed to determine which specific pathologies can be treated, if maintenance treatment is necessary, and long-term safety concerns,” the authors concluded.

In another review, researchers analyzed 64 studies related to vaginal laser therapy for GSM. Of these, 47 were before and after studies without a control group, 10 were controlled intervention studies, and 7 were observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Vaginal laser treatment “seems to improve scores on the visual analogue scale, Female Sexual Function Index, and the Vaginal Health Index over the short term,” the authors wrote. “Safety outcomes are underreported and short term. Further well-designed clinical trials with sham-laser control groups and evaluating objective variables are needed to provide the best evidence on efficacy.”

“Lasers and energy-based devices are now considered alternative therapeutic modalities for genitourinary conditions,” Dr. Alexiades concluded. “The shortcomings in the literature with respect to lasers and device treatments demonstrate the need for the consensus on best practices and protocols.”

During a separate presentation at the meeting, Michael Gold, MD, highlighted data from Grand View Research, a market research database, which estimated that the global women’s health and wellness market is valued at more than $31 billion globally and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 4.8% from 2022 to 2030.

“Sales of women’s health energy-based devices continue to grow as new technologies are developed,” said Dr. Gold, a Nashville, Tenn.–based dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon who is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. “Evolving societal norms have made discussions about feminine health issues acceptable. Suffering in silence is no longer necessary or advocated.”

Dr. Alexiades disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela Lasers, Lumenis, Allergan/AbbVie, InMode, and Endymed. She is also the founder and CEO of Macrene Actives. Dr. Gold disclosed that he is a consultant to and/or an investigator and a speaker for Joylux, InMode, and Alma Lasers.

PHOENIX –

“Even a cursory review of PubMed today yields over 100,000 results” on this topic, Macrene R. Alexiades, MD, PhD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Add to that radiofrequency and various diagnoses, the number of publications has skyrocketed, particularly over the last 10 years.”

What has been missing from this hot research topic all these years, she continued, is that no one has distilled this pile of data into a practical guide for office-based clinicians who use lasers and energy-based devices for genitourinary conditions – until now. Working with experts in gynecology and urogynecology, Dr. Alexiades spearheaded a 2-year-long effort to assemble a document on optimal protocols and best practices for genitourinary application of lasers and energy-based devices. The document, published soon after the ASLMS meeting in Lasers in Medicine and Surgery, includes a table that lists the current Food and Drug Administration approval status of devices in genitourinary applications, as well as individual sections dedicated to fractional lasers, radiofrequency (RF) devices, and high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology. It concludes with a section on the current status of clearances and future pathways.