User login

Child ‘Mis’behavior – What’s ‘mis’ing?

“What kind of parent are you? Why don’t you straighten him out!” rants the woman being jostled in the grocery store by your patient. “Easy for you to say,” thinks your patient’s frazzled and now insulted parent.

Blaming the parent for an out-of-control child has historically been a common refrain of neighbors, relatives, and even strangers. But considering child behavior as resulting from both parent and child factors is central to the current transactional model of child development. In this model, mismatch of the parent’s and child’s response patterns is seen as setting them up for chronically rough interactions around parent requests/demands. A parent escalating quickly from a briefly stated request to a tirade may create more tension paired with an anxious child who takes time to act, for example. Once a parent (and ultimately the child) recognize patterns in what leads to conflict, they can become more proactive in predicting and negotiating these situations. Ross Greene, PhD, explains this in his book “The Explosive Child,” calling the method Collaborative Problem Solving (now Collaborative & Proactive Solutions or CPS).

While there are general principles parents can use to modify what they consider “mis”behaviors, these methods often do not account for the “missing” skills of the individual child (and parent) predisposing to those “mis”takes. Thinking of misbehaviors as being because of a kind of “learning disability” in the child rather than willful defiance can help cool off interactions by instead focusing on solving the underlying problem.

What kinds of “gaps in skills” set a child up for defiant or explosive reactions? If you think about what features of children, and parent-child relationships are associated with harmonious interactions this becomes evident. Children over 3 who are patient, easygoing, flexible or adaptable, and good at transitions and problem-solving can delay gratification and tolerate frustration, regulate their emotions, explain their desires, and multitask. They are better at reading the parent’s needs and intent and tend to interpret requests as positive or at least neutral and are more likely to comply with parent requests without a fuss.

What? No kid you know is great at all of these? These skills, at best variable, develop with maturation. Some are part of temperament, considered normal variation in personality. For example, so-called difficult temperament includes low adaptability, high-intensity reactions, low regularity, tendency to withdraw, and negative mood. But in the extreme, weaknesses in these skills are core to or comorbid with diagnosable mental health disorders. Defiance and irritable responses are criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and less severe categories called aggressive/oppositional problem or variation. ODD is often found in children diagnosed with ADHD (65%), Tourette’s (15%-65%), depression (70% if severe), bipolar disorder (85%), OCD, anxiety (45%), autism, and language-processing disorders (55%), or trauma. These conditions variably include lower emotion regulation, poorer executive functioning including poor task shifting and impulsivity, obsessiveness, lower expressive and receptive communication skills, and less social awareness that facilitates harmonious problem solving.

The basic components of the CPS approach to addressing parent-child conflict sound intuitive but defining them clearly is important when families are stuck. There are three levels of plans. If the problem is an emergency or nonnegotiable, e.g., child hurting the cat, it may call for Plan A – parent-imposed solutions, sometimes with consequences or rewards. As children mature, Plan A should be used less frequently. If solving the problem is not a top life priority, Plan C – postponing action, may be appropriate. Plan C highlights that behavior change is a long-term project and “picking your fights” is important.

The biggest value of CPS for resolving behavior problems comes from intermediate Plan B. In Plan B the first step of problem solving for parents facing child defiance or upset is to empathically and nonjudgmentally figure out the child’s concern. Questions such as “I’ve noticed that when I remind you that it is trash night you start shouting. What’s up with that?” then patiently asking about the who, what, where, and when of their concern and checking to ensure understanding. Specificity is important as well as noting times when the reaction occurs or not.

Once the child’s concern is clear, e.g., feeling that the demand to take out the trash now interrupts his games during the only time his friends are online, the parents should echo the child’s concern then express their own concern about how the behavior is affecting them and others, potentially including the child; e.g., mother is so upset by the shouting that she can’t sleep, and worry that the child is not learning responsibility, and then checking for child understanding.

Finally, the parent invites brainstorming for a solution that addresses both of their concerns, first asking the child for suggestions, aiming for a strategy that is realistic and specific. Children reluctant to make suggestions may need more time and the parent may be wondering “if there is a way for both of our concerns to be addressed.” Solutions chosen are then tried for several weeks, success tracked, and needed changes negotiated.

For parents, using a collaborative approach to dealing with their child’s behavior takes skills they may not have at the moment, or ever. Especially under the stresses of COVID-19 lockdown, taking a step back from an encounter to consider lack of a skill to turn off the video game promptly when a Zoom meeting starts is challenging. Parents may also genetically share the child’s predisposing ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD, or weakness in communication or social sensitivity.

Sometimes part of the solution for a conflict is for the parent to reduce expectations. This requires understanding and accepting the child’s cognitive or emotional limitations. Reducing expectations is ideally done before a request rather than by giving in after it, which reinforces protests. For authoritarian adults rigid in their belief that parents are boss, changing expectations can be tough and can feel like losing control or failing as a leader. One benefit of working with a CPS coach (see livesinthebalance.org or ThinkKids.org) is to help parents identify their own limitations.

Predicting the types of demands that tend to create conflict, such as to act immediately or be flexible about options, allows parents to prioritize those requests for calmer moments or when there is more time for discussion. Reviewing a checklist of common gaps in skills and creating a list of expectations and triggers that are difficult for the child helps the family be more proactive in developing solutions. Authors of CPS have validated a checklist of skill deficits, “Thinking Skills Inventory,” to facilitate detection of gaps that is educational plus useful for planning specific solutions.

CPS has been shown in randomized trials with both parent groups and in home counseling to be as effective as Parent Training in reducing oppositional behavior and reducing maternal stress, with effects lasting even longer.

CPS Plan B notably has no reward or punishment components as it assumes the child wants to behave acceptably but can’t; has the “will but not the skill.” When skill deficits are worked around the child is satisfied with complying and pleasing the parents. The idea of a “function” of the misbehavior for the child of gaining attention or reward or avoiding consequences is reinterpreted as serving to communicate the problem the child is having trouble in meeting the parent’s demand. When the parent understands and helps the child solve the problem his/her misbehavior is no longer needed. A benefit of the communication and mutual problem solving used in CPS is on not only improving behavior but empowering parents and children, building parental empathy, and improving child skills.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication is as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Reference

Greene RW et al. A transactional model of oppositional behavior: Underpinnings of the Collaborative Problem Solving approach. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):67-75.

“What kind of parent are you? Why don’t you straighten him out!” rants the woman being jostled in the grocery store by your patient. “Easy for you to say,” thinks your patient’s frazzled and now insulted parent.

Blaming the parent for an out-of-control child has historically been a common refrain of neighbors, relatives, and even strangers. But considering child behavior as resulting from both parent and child factors is central to the current transactional model of child development. In this model, mismatch of the parent’s and child’s response patterns is seen as setting them up for chronically rough interactions around parent requests/demands. A parent escalating quickly from a briefly stated request to a tirade may create more tension paired with an anxious child who takes time to act, for example. Once a parent (and ultimately the child) recognize patterns in what leads to conflict, they can become more proactive in predicting and negotiating these situations. Ross Greene, PhD, explains this in his book “The Explosive Child,” calling the method Collaborative Problem Solving (now Collaborative & Proactive Solutions or CPS).

While there are general principles parents can use to modify what they consider “mis”behaviors, these methods often do not account for the “missing” skills of the individual child (and parent) predisposing to those “mis”takes. Thinking of misbehaviors as being because of a kind of “learning disability” in the child rather than willful defiance can help cool off interactions by instead focusing on solving the underlying problem.

What kinds of “gaps in skills” set a child up for defiant or explosive reactions? If you think about what features of children, and parent-child relationships are associated with harmonious interactions this becomes evident. Children over 3 who are patient, easygoing, flexible or adaptable, and good at transitions and problem-solving can delay gratification and tolerate frustration, regulate their emotions, explain their desires, and multitask. They are better at reading the parent’s needs and intent and tend to interpret requests as positive or at least neutral and are more likely to comply with parent requests without a fuss.

What? No kid you know is great at all of these? These skills, at best variable, develop with maturation. Some are part of temperament, considered normal variation in personality. For example, so-called difficult temperament includes low adaptability, high-intensity reactions, low regularity, tendency to withdraw, and negative mood. But in the extreme, weaknesses in these skills are core to or comorbid with diagnosable mental health disorders. Defiance and irritable responses are criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and less severe categories called aggressive/oppositional problem or variation. ODD is often found in children diagnosed with ADHD (65%), Tourette’s (15%-65%), depression (70% if severe), bipolar disorder (85%), OCD, anxiety (45%), autism, and language-processing disorders (55%), or trauma. These conditions variably include lower emotion regulation, poorer executive functioning including poor task shifting and impulsivity, obsessiveness, lower expressive and receptive communication skills, and less social awareness that facilitates harmonious problem solving.

The basic components of the CPS approach to addressing parent-child conflict sound intuitive but defining them clearly is important when families are stuck. There are three levels of plans. If the problem is an emergency or nonnegotiable, e.g., child hurting the cat, it may call for Plan A – parent-imposed solutions, sometimes with consequences or rewards. As children mature, Plan A should be used less frequently. If solving the problem is not a top life priority, Plan C – postponing action, may be appropriate. Plan C highlights that behavior change is a long-term project and “picking your fights” is important.

The biggest value of CPS for resolving behavior problems comes from intermediate Plan B. In Plan B the first step of problem solving for parents facing child defiance or upset is to empathically and nonjudgmentally figure out the child’s concern. Questions such as “I’ve noticed that when I remind you that it is trash night you start shouting. What’s up with that?” then patiently asking about the who, what, where, and when of their concern and checking to ensure understanding. Specificity is important as well as noting times when the reaction occurs or not.

Once the child’s concern is clear, e.g., feeling that the demand to take out the trash now interrupts his games during the only time his friends are online, the parents should echo the child’s concern then express their own concern about how the behavior is affecting them and others, potentially including the child; e.g., mother is so upset by the shouting that she can’t sleep, and worry that the child is not learning responsibility, and then checking for child understanding.

Finally, the parent invites brainstorming for a solution that addresses both of their concerns, first asking the child for suggestions, aiming for a strategy that is realistic and specific. Children reluctant to make suggestions may need more time and the parent may be wondering “if there is a way for both of our concerns to be addressed.” Solutions chosen are then tried for several weeks, success tracked, and needed changes negotiated.

For parents, using a collaborative approach to dealing with their child’s behavior takes skills they may not have at the moment, or ever. Especially under the stresses of COVID-19 lockdown, taking a step back from an encounter to consider lack of a skill to turn off the video game promptly when a Zoom meeting starts is challenging. Parents may also genetically share the child’s predisposing ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD, or weakness in communication or social sensitivity.

Sometimes part of the solution for a conflict is for the parent to reduce expectations. This requires understanding and accepting the child’s cognitive or emotional limitations. Reducing expectations is ideally done before a request rather than by giving in after it, which reinforces protests. For authoritarian adults rigid in their belief that parents are boss, changing expectations can be tough and can feel like losing control or failing as a leader. One benefit of working with a CPS coach (see livesinthebalance.org or ThinkKids.org) is to help parents identify their own limitations.

Predicting the types of demands that tend to create conflict, such as to act immediately or be flexible about options, allows parents to prioritize those requests for calmer moments or when there is more time for discussion. Reviewing a checklist of common gaps in skills and creating a list of expectations and triggers that are difficult for the child helps the family be more proactive in developing solutions. Authors of CPS have validated a checklist of skill deficits, “Thinking Skills Inventory,” to facilitate detection of gaps that is educational plus useful for planning specific solutions.

CPS has been shown in randomized trials with both parent groups and in home counseling to be as effective as Parent Training in reducing oppositional behavior and reducing maternal stress, with effects lasting even longer.

CPS Plan B notably has no reward or punishment components as it assumes the child wants to behave acceptably but can’t; has the “will but not the skill.” When skill deficits are worked around the child is satisfied with complying and pleasing the parents. The idea of a “function” of the misbehavior for the child of gaining attention or reward or avoiding consequences is reinterpreted as serving to communicate the problem the child is having trouble in meeting the parent’s demand. When the parent understands and helps the child solve the problem his/her misbehavior is no longer needed. A benefit of the communication and mutual problem solving used in CPS is on not only improving behavior but empowering parents and children, building parental empathy, and improving child skills.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication is as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Reference

Greene RW et al. A transactional model of oppositional behavior: Underpinnings of the Collaborative Problem Solving approach. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):67-75.

“What kind of parent are you? Why don’t you straighten him out!” rants the woman being jostled in the grocery store by your patient. “Easy for you to say,” thinks your patient’s frazzled and now insulted parent.

Blaming the parent for an out-of-control child has historically been a common refrain of neighbors, relatives, and even strangers. But considering child behavior as resulting from both parent and child factors is central to the current transactional model of child development. In this model, mismatch of the parent’s and child’s response patterns is seen as setting them up for chronically rough interactions around parent requests/demands. A parent escalating quickly from a briefly stated request to a tirade may create more tension paired with an anxious child who takes time to act, for example. Once a parent (and ultimately the child) recognize patterns in what leads to conflict, they can become more proactive in predicting and negotiating these situations. Ross Greene, PhD, explains this in his book “The Explosive Child,” calling the method Collaborative Problem Solving (now Collaborative & Proactive Solutions or CPS).

While there are general principles parents can use to modify what they consider “mis”behaviors, these methods often do not account for the “missing” skills of the individual child (and parent) predisposing to those “mis”takes. Thinking of misbehaviors as being because of a kind of “learning disability” in the child rather than willful defiance can help cool off interactions by instead focusing on solving the underlying problem.

What kinds of “gaps in skills” set a child up for defiant or explosive reactions? If you think about what features of children, and parent-child relationships are associated with harmonious interactions this becomes evident. Children over 3 who are patient, easygoing, flexible or adaptable, and good at transitions and problem-solving can delay gratification and tolerate frustration, regulate their emotions, explain their desires, and multitask. They are better at reading the parent’s needs and intent and tend to interpret requests as positive or at least neutral and are more likely to comply with parent requests without a fuss.

What? No kid you know is great at all of these? These skills, at best variable, develop with maturation. Some are part of temperament, considered normal variation in personality. For example, so-called difficult temperament includes low adaptability, high-intensity reactions, low regularity, tendency to withdraw, and negative mood. But in the extreme, weaknesses in these skills are core to or comorbid with diagnosable mental health disorders. Defiance and irritable responses are criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and less severe categories called aggressive/oppositional problem or variation. ODD is often found in children diagnosed with ADHD (65%), Tourette’s (15%-65%), depression (70% if severe), bipolar disorder (85%), OCD, anxiety (45%), autism, and language-processing disorders (55%), or trauma. These conditions variably include lower emotion regulation, poorer executive functioning including poor task shifting and impulsivity, obsessiveness, lower expressive and receptive communication skills, and less social awareness that facilitates harmonious problem solving.

The basic components of the CPS approach to addressing parent-child conflict sound intuitive but defining them clearly is important when families are stuck. There are three levels of plans. If the problem is an emergency or nonnegotiable, e.g., child hurting the cat, it may call for Plan A – parent-imposed solutions, sometimes with consequences or rewards. As children mature, Plan A should be used less frequently. If solving the problem is not a top life priority, Plan C – postponing action, may be appropriate. Plan C highlights that behavior change is a long-term project and “picking your fights” is important.

The biggest value of CPS for resolving behavior problems comes from intermediate Plan B. In Plan B the first step of problem solving for parents facing child defiance or upset is to empathically and nonjudgmentally figure out the child’s concern. Questions such as “I’ve noticed that when I remind you that it is trash night you start shouting. What’s up with that?” then patiently asking about the who, what, where, and when of their concern and checking to ensure understanding. Specificity is important as well as noting times when the reaction occurs or not.

Once the child’s concern is clear, e.g., feeling that the demand to take out the trash now interrupts his games during the only time his friends are online, the parents should echo the child’s concern then express their own concern about how the behavior is affecting them and others, potentially including the child; e.g., mother is so upset by the shouting that she can’t sleep, and worry that the child is not learning responsibility, and then checking for child understanding.

Finally, the parent invites brainstorming for a solution that addresses both of their concerns, first asking the child for suggestions, aiming for a strategy that is realistic and specific. Children reluctant to make suggestions may need more time and the parent may be wondering “if there is a way for both of our concerns to be addressed.” Solutions chosen are then tried for several weeks, success tracked, and needed changes negotiated.

For parents, using a collaborative approach to dealing with their child’s behavior takes skills they may not have at the moment, or ever. Especially under the stresses of COVID-19 lockdown, taking a step back from an encounter to consider lack of a skill to turn off the video game promptly when a Zoom meeting starts is challenging. Parents may also genetically share the child’s predisposing ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD, or weakness in communication or social sensitivity.

Sometimes part of the solution for a conflict is for the parent to reduce expectations. This requires understanding and accepting the child’s cognitive or emotional limitations. Reducing expectations is ideally done before a request rather than by giving in after it, which reinforces protests. For authoritarian adults rigid in their belief that parents are boss, changing expectations can be tough and can feel like losing control or failing as a leader. One benefit of working with a CPS coach (see livesinthebalance.org or ThinkKids.org) is to help parents identify their own limitations.

Predicting the types of demands that tend to create conflict, such as to act immediately or be flexible about options, allows parents to prioritize those requests for calmer moments or when there is more time for discussion. Reviewing a checklist of common gaps in skills and creating a list of expectations and triggers that are difficult for the child helps the family be more proactive in developing solutions. Authors of CPS have validated a checklist of skill deficits, “Thinking Skills Inventory,” to facilitate detection of gaps that is educational plus useful for planning specific solutions.

CPS has been shown in randomized trials with both parent groups and in home counseling to be as effective as Parent Training in reducing oppositional behavior and reducing maternal stress, with effects lasting even longer.

CPS Plan B notably has no reward or punishment components as it assumes the child wants to behave acceptably but can’t; has the “will but not the skill.” When skill deficits are worked around the child is satisfied with complying and pleasing the parents. The idea of a “function” of the misbehavior for the child of gaining attention or reward or avoiding consequences is reinterpreted as serving to communicate the problem the child is having trouble in meeting the parent’s demand. When the parent understands and helps the child solve the problem his/her misbehavior is no longer needed. A benefit of the communication and mutual problem solving used in CPS is on not only improving behavior but empowering parents and children, building parental empathy, and improving child skills.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication is as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Reference

Greene RW et al. A transactional model of oppositional behavior: Underpinnings of the Collaborative Problem Solving approach. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):67-75.

More Americans hospitalized, readmitted for heart failure

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

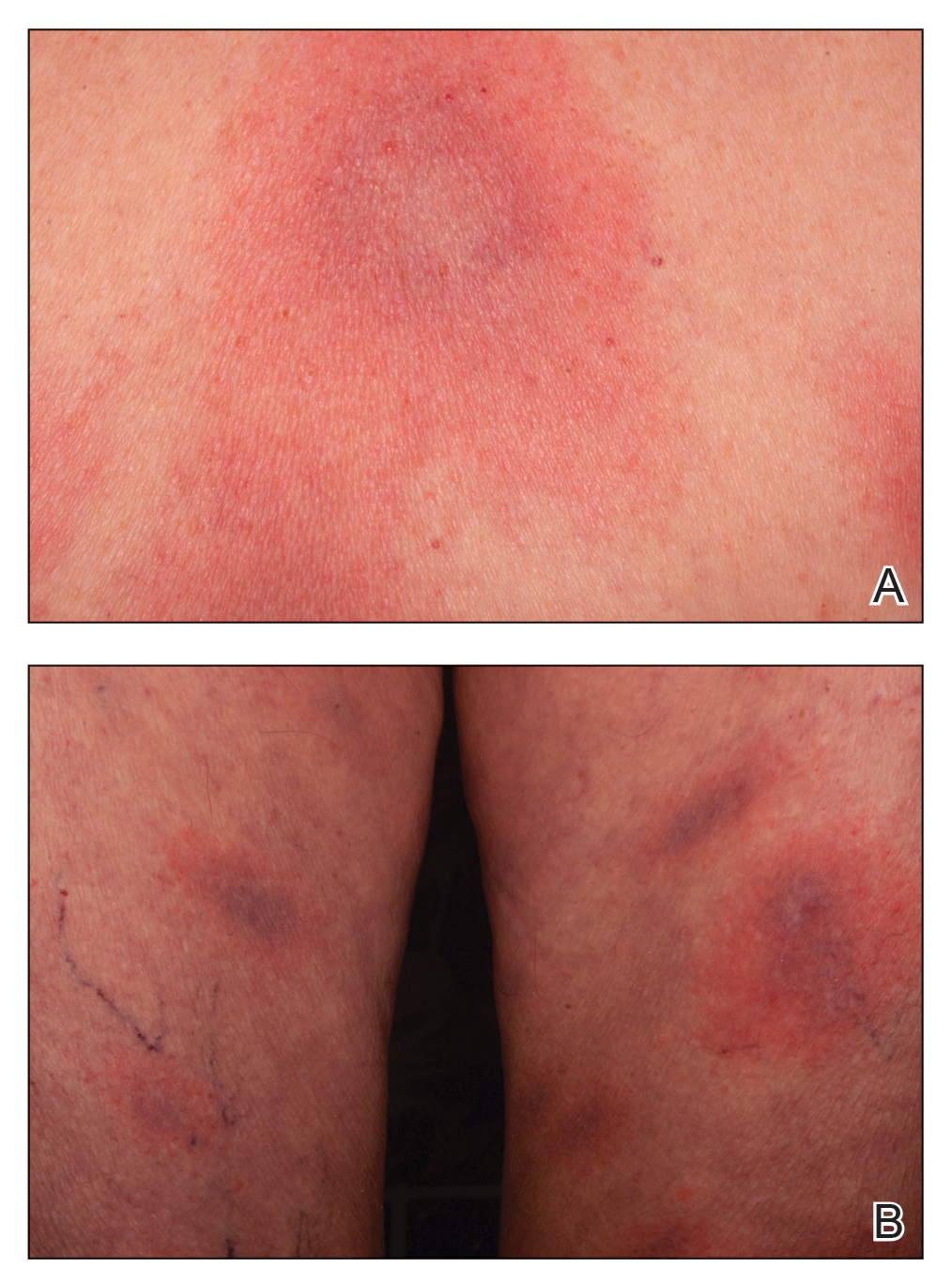

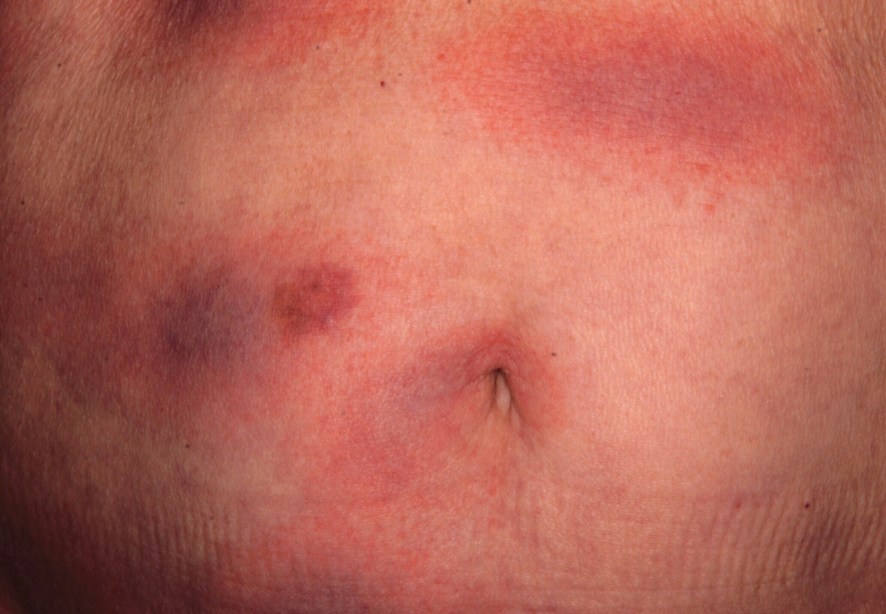

Multifocal Annular Pink Plaques With a Central Violaceous Hue

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Erythema Chronicum Migrans

Empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days was initiated for suspected early disseminated Lyme disease manifesting as disseminated multifocal erythema chronicum migrans (Figure). Lyme screening immunoassay and confirmatory IgM Western blot testing subsequently were found to be positive. The clinical history of recent travel to an endemic area and tick bite combined with the recent onset of multifocal erythema migrans lesions, systemic symptoms, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive Lyme serology supported the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

The appropriate clinical context and cutaneous morphology are key when considering the differential diagnosis for multifocal annular lesions. Several entities comprised the differential diagnosis considered in our patient. Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that can present with fever and varying painful cutaneous lesions. It often is associated with certain medications, underlying illnesses, and infections.1 Our patient’s lesions were not painful, and she had no notable medical history, recent infections, or new medication use, making Sweet syndrome unlikely. A fixed drug eruption was low on the differential, as the patient denied starting any new medications within the 3 months prior to presentation. Erythema multiforme is an acute-onset immunemediated condition of the skin and mucous membranes that typically affects young adults and often is associated with infection (eg, herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae) or medication use. Cutaneous lesions typically are self-limited, less than 3 cm targets with 3 concentric distinct color zones, often with central bullae or erosions. Although erythema multiforme was higher on the differential, it was less likely, as the patient lacked mucosal lesions and did not have symptoms of underlying herpetic or mycoplasma infection, and the clinical picture was more consistent with Lyme disease. Lastly, the failure for individual skin lesions to resolve within

24 hours excluded the diagnosis of urticaria.

Lyme disease is a tick-borne illness caused by 3 species of the Borrelia spirochete: Borrelia burgdorferi, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii.2 In the United States, the disease predominantly is caused by B burgdorferi that is endemic in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.3 There are 3 stages of Lyme disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated disease. Early localized disease typically presents with a characteristic single erythema migrans (EM) lesion 3 to 30 days following a bite by the tick Ixodes scapularis.2 The EM lesion gradually can enlarge over a period of several days, reaching up to 12 inches in diameter.2 Early disseminated disease can occur weeks to months following a tick bite and may present with systemic symptoms, multiple widespread

EM lesions, neurologic features such as meningitis or facial nerve palsy, and/or cardiac manifestations such as atrioventricular block or myocarditis. Late disseminated disease can present with chronic arthritis or encephalopathy after months to years if the disease is left untreated.4

Early localized Lyme disease can be diagnosed clinically if the characteristic EM lesion is present in a patient who visited an endemic area. Laboratory testing and Lyme serology are neither required nor recommended in these cases, as the lesion often appears before adequate time has lapsed to develop an adaptive immune response to the organism.5 In contrast, Lyme serology should be ordered in any patient who meets all of the following criteria: (1) patient lives in or has recently traveled to an area endemic for Lyme disease, (2) presence of a risk factor for tick exposure, and (3) symptoms consistent with early disseminated or late Lyme disease. Patients with signs of early or late disseminated disease typically are seropositive, as IgM antibodies can be detected within 2 weeks of onset of the EM lesion and IgG antibodies within 2 to 6 weeks.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-tiered approach when testing for Lyme disease.7 A screening test with high sensitivity such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or an immunofluorescence assay initially should be performed.7 If results of the screening test are equivocal or positive, secondary confirmatory testing should be performed via IgM, with or without IgG Western immunoblot assay.7 Biopsy with histologic evaluation can reveal nonspecific findings of vascular endothelial injury and increased mucin deposition. Patients with suspected Lyme disease should immediately be started on empiric treatment with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 10 days (14–28 days if there is concern for dissemination) to prevent post-Lyme sequelae.5 Our patient’s cutaneous lesions responded to oral doxycycline.

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

- Sweet’s syndrome. Mayo Clinic. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sweets-syndrome /symptoms-causes/syc-20351117

- Steere AC. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:115-125.

- Lyme disease maps: most recent year. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 22, 2019. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/datasurveillance /maps-recent.html.

- Steere AC, Sikand VK. The present manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: a review. JAMA. 2016;315:1767-1777.

- Shapiro ED. Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). Pediatr Rev. 2014; 35:500-509.

- Mead P, Petersen J, Hinckley A. Updated CDC recommendation for serologic diagnosis of Lyme disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:703

An otherwise healthy 78-year-old woman presented with a diffuse, mildly itchy rash of 5 days’ duration with associated fatigue, chills, decreased appetite, and nausea. She reported waking up with her arms “feeling like they weigh a ton.” She denied any pain, bleeding, or oozing and was unsure if new spots were continuing to develop. The patient reported having allergies to numerous medications but denied any new medications or recent illnesses. She had recently spent time on a farm in Minnesota, and upon further questioning she recalled a tick bite 2 months prior to presentation. She stated that she removed the nonengorged tick and that it could not have been attached for more than 24 hours. Her medical and family history were unremarkable. Physical examination showed multiple annular pink plaques with a central violaceous hue in a generalized distribution involving the face, trunk, arms, and legs with mild erythema of the palms. The plantar surfaces were clear, and there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy. The remainder of the physical examination and review of systems was negative. Laboratory screening was notable for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level with negative antinuclear antibodies.

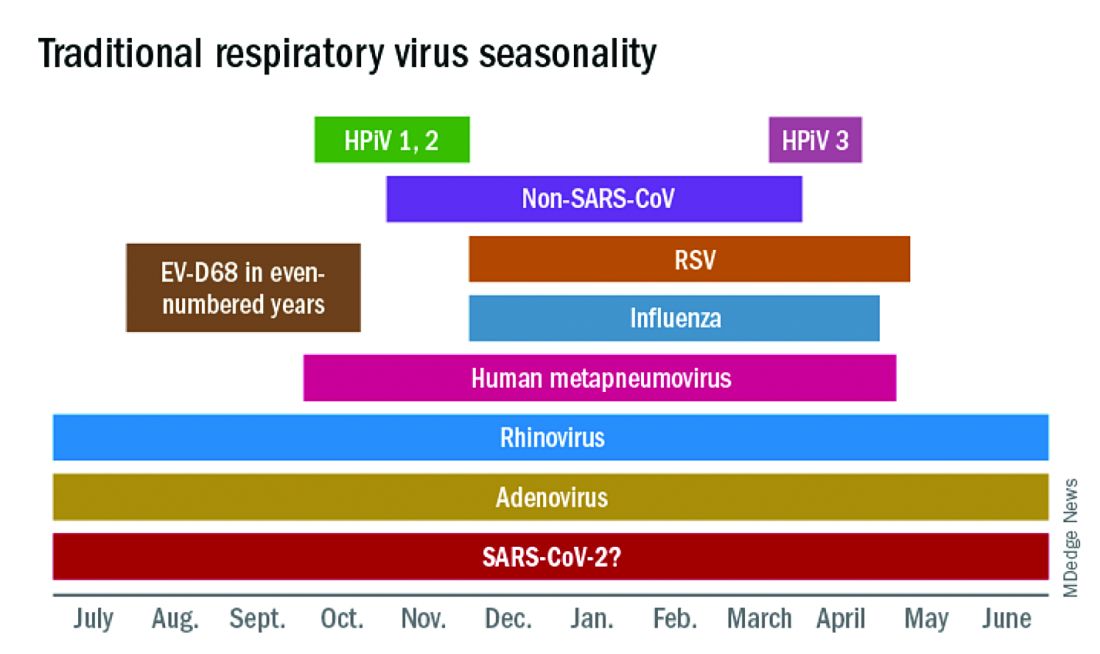

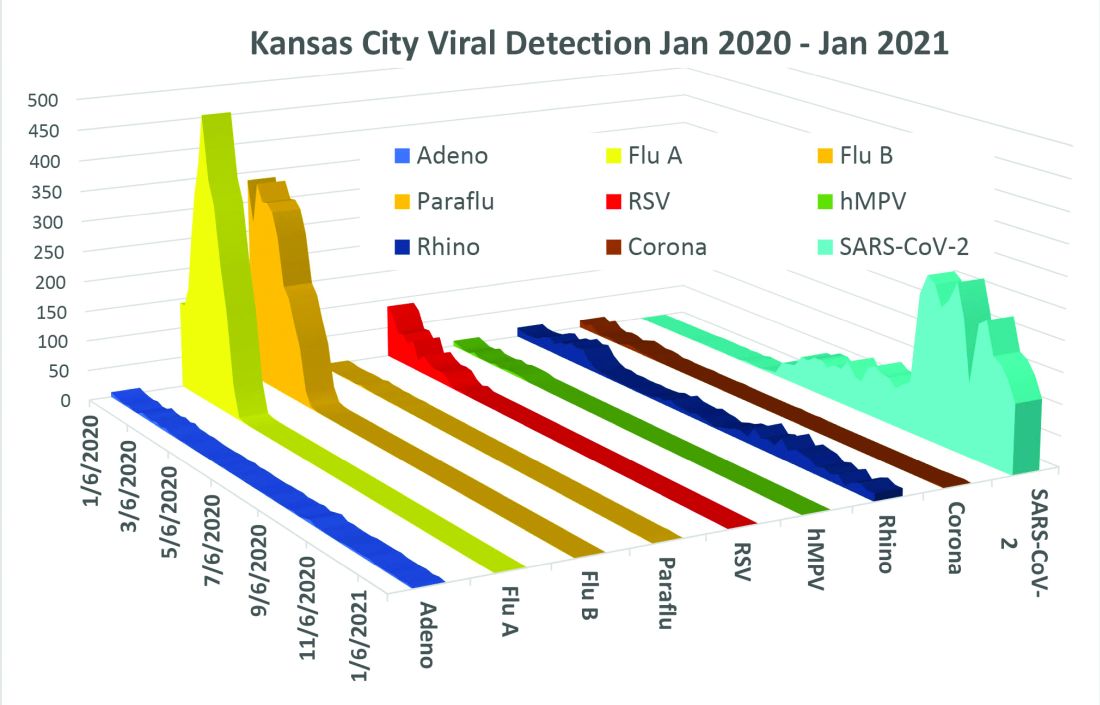

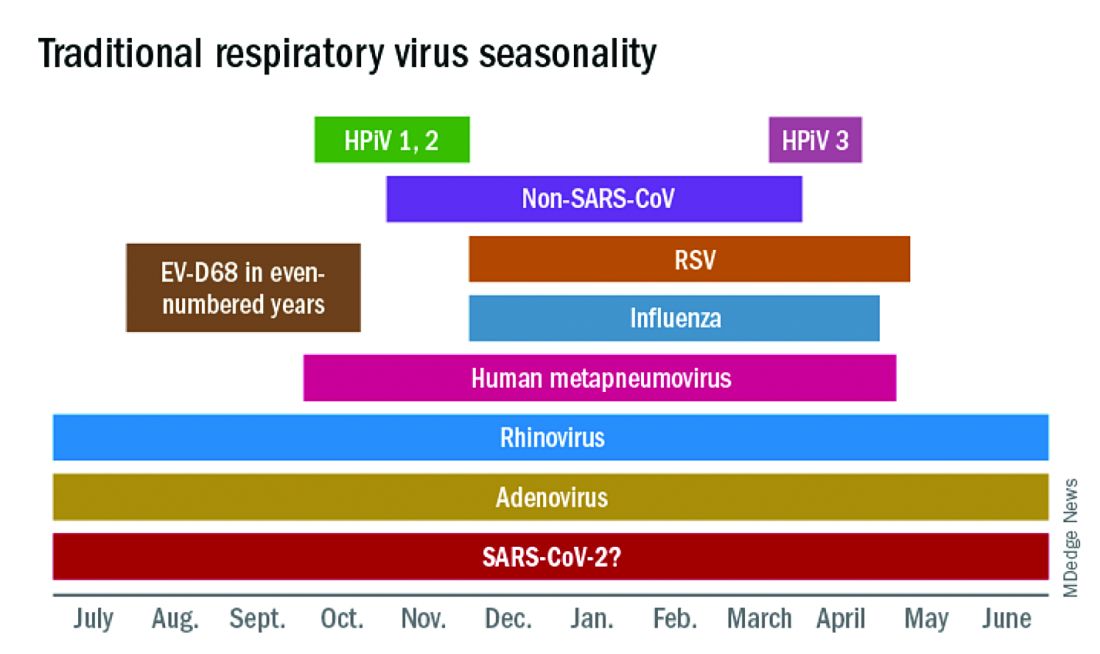

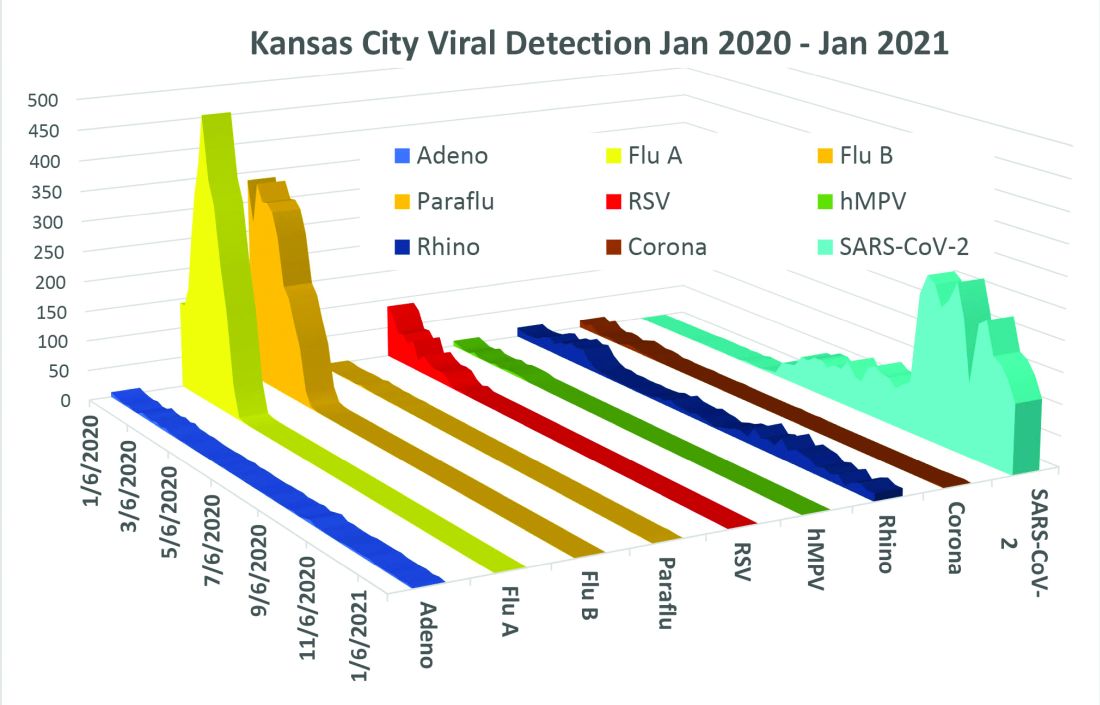

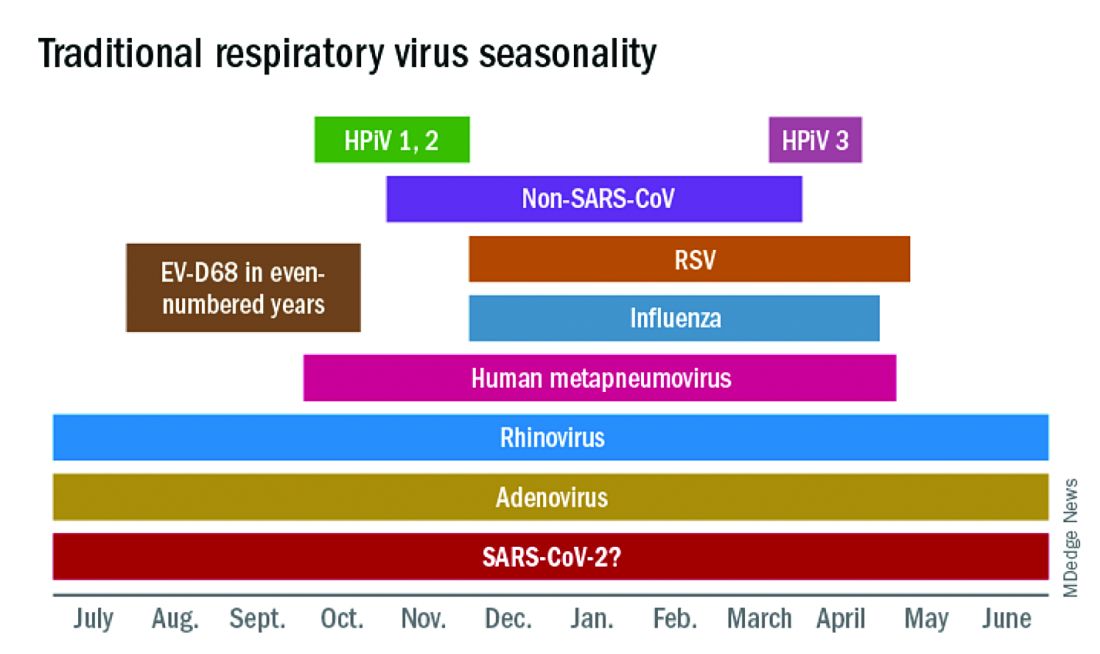

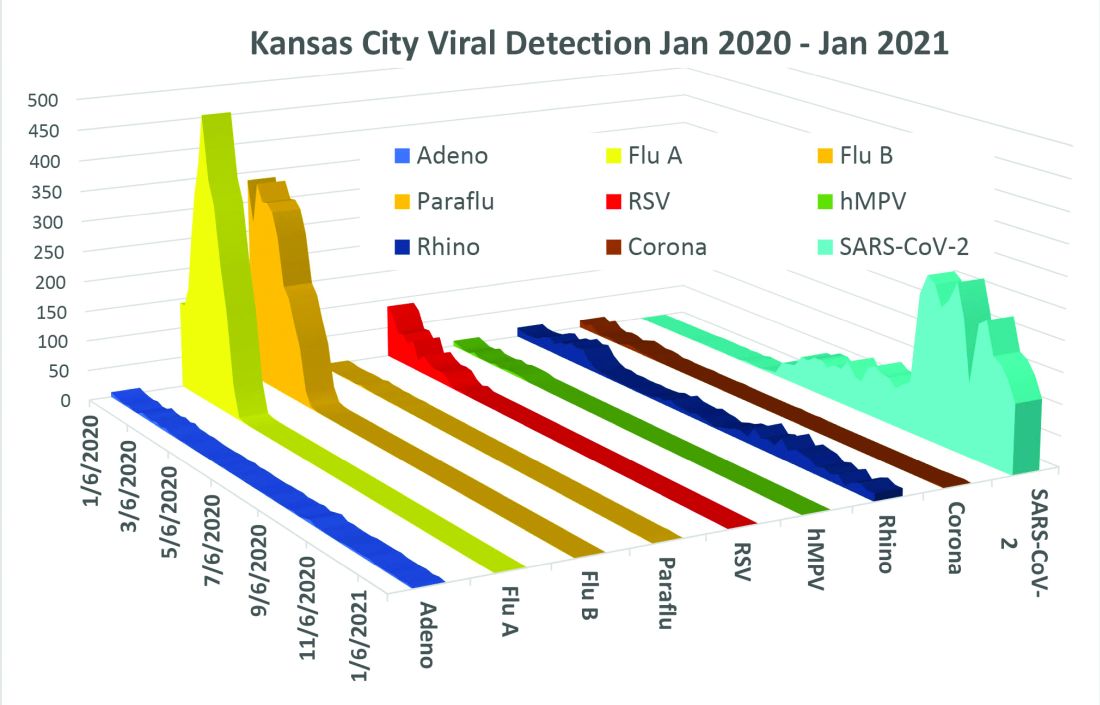

The lost year – even for common respiratory viruses

In this column in September 2020, you read how common respiratory viruses’ seasons are usually so predictable, each virus arising, peaking, and then dying out in a predictable virus parade (Figure 1).1 Well, the predictable virus seasonal pattern was lost in 2020. Since March of 2020, it is striking how little activity was detected for the usual seasonal viruses in Kansas City after mid-March 2020 (Figure 2).2 So, my concern in September 2020 for possible rampant coinfections of common viruses with or in tandem with SARS-CoV-2 did not pan out. That said, the seasons for non–SARS-CoV-2 viruses did change; I just didn’t expect they would nearly disappear.

The 2020 winter-spring. In the first quarter (the last part of the overall 2019-2020 respiratory viral season), viral detections were chugging along as usual up to mid-March (Figure 2); influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and rhinovirus were the big players.

Influenza. In most years, influenza type B leads off and is quickly replaced by type A only to see B reemerge to end influenza season in March-April. In early 2020, both influenza type A and influenza type B cocirculated nearly equally, but both dropped like a rock in mid-March (Figure 2).2 Neither type has been seen since with the exception of sporadic detections – perhaps being false positives.

RSV. In the usual year in temperate mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere, RSV season usually starts in early December, peaks in January-March, and declines gradually until the end of RSV season in April (Figure 1). In southern latitudes, RSV is less seasonal, being present most of the year, but peaking in “winter” months.3 But in 2020, RSV also disappeared in mid-March and has yet to reappear.

Other viruses. Small bumps in detection of parainfluenza of varying types usually frame influenza season, one B bump in early autumn and another in April-May. In most years, human metapneumovirus is detected on and off, with worse years at 2- to 3-year intervals. Adenovirus occurs year-round with bumps as children get back to school in autumn. Yet in 2020, almost no parainfluenza, adenovirus, common coronaviruses, or human metapneumovirus were detected in either spring or autumn. This was supposed to be a banner summer-autumn for EV-D68 – but almost none was detected. Interestingly, the cockroach of viruses, rhinovirus, has its usual year (Figure 2).

What happened? Intense social mitigation interventions, including social distancing and closing daycares and schools, were likely major factors.4 For influenza, vaccine may have helped but uptake was not remarkably better than most prior years. There may have been “viral competition,”where a new or highly transmissible virus outcompetes less-transmissible viruses with lower affinity for respiratory receptors.5,6 Note that SARS-CoV-2 has very high affinity for the ACE2 receptor and has been highly prevalent. So, SARS-CoV-2 could fit the theoretical mold for a virus that outcompetes others.

Does it matter for the future? Blunted 2019-2020 and nearly absent 2020-2021 respiratory virus season may have set the stage for intense 2021-2022 rebounds for the non–SARS-CoV-2 viruses. We now have two whole and one partial birth cohort with no experience with seasonal respiratory viruses, including EV-D68 (and nonrespiratory viruses too – like norovirus, parechovirus, and other enteroviruses). Most viruses have particularly bad seasons every 2-3 years, thought to be caused by increasing accumulation of susceptible individuals in consecutive birth cohorts until a critical mass of susceptible individuals is achieved. The excess in susceptible individuals means that each contagious case is likely to expose one or more susceptible individuals, enhancing transmission and infection numbers in an ever-extending ripple effect. We have never had this many children aged under 3 years with no immunity to influenza, RSV, etc. So unless mother nature is kind (when has that happened lately?), expect rebound years for seasonal viruses as children return to daycare/schools and as social mitigation becomes less necessary in the waning pandemic.

Options? If you ramped up telehealth visits for the pandemic, that may be a saving grace, i.e., more efficiency so more “visits” can be completed per day, and less potential contact in reception rooms between well and ill children. And if there was ever a time to really intensify efforts to immunize all our pediatric patients, the next two seasons are just that. Adding a bit of a warning to families with young children also seems warranted. If they understand that, while 2021-2022 will be better for SARS-CoV-2, it is likely going to be worse for the other viruses.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Harrison CJ. 2020-2021 respiratory viral season: Onset, presentations, and testing likely to differ in pandemic, Pediatric News: September 17, 2020.

2. Olsen SJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1305-9.

3. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Surveillance. http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/respiratory-syncytial-virus/_documents/2021-w4-rsv-summary.pdf

4. Baker RE et al. PNAS. Dec 2020 117;(48):30547-53.

5. Sema Nickbakhsh et al. PNAS. Dec 2019 116;(52):27142-50.

6. Kirsten M et al. PNAS. Mar 2020 117;(13):6987.

In this column in September 2020, you read how common respiratory viruses’ seasons are usually so predictable, each virus arising, peaking, and then dying out in a predictable virus parade (Figure 1).1 Well, the predictable virus seasonal pattern was lost in 2020. Since March of 2020, it is striking how little activity was detected for the usual seasonal viruses in Kansas City after mid-March 2020 (Figure 2).2 So, my concern in September 2020 for possible rampant coinfections of common viruses with or in tandem with SARS-CoV-2 did not pan out. That said, the seasons for non–SARS-CoV-2 viruses did change; I just didn’t expect they would nearly disappear.

The 2020 winter-spring. In the first quarter (the last part of the overall 2019-2020 respiratory viral season), viral detections were chugging along as usual up to mid-March (Figure 2); influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and rhinovirus were the big players.

Influenza. In most years, influenza type B leads off and is quickly replaced by type A only to see B reemerge to end influenza season in March-April. In early 2020, both influenza type A and influenza type B cocirculated nearly equally, but both dropped like a rock in mid-March (Figure 2).2 Neither type has been seen since with the exception of sporadic detections – perhaps being false positives.

RSV. In the usual year in temperate mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere, RSV season usually starts in early December, peaks in January-March, and declines gradually until the end of RSV season in April (Figure 1). In southern latitudes, RSV is less seasonal, being present most of the year, but peaking in “winter” months.3 But in 2020, RSV also disappeared in mid-March and has yet to reappear.

Other viruses. Small bumps in detection of parainfluenza of varying types usually frame influenza season, one B bump in early autumn and another in April-May. In most years, human metapneumovirus is detected on and off, with worse years at 2- to 3-year intervals. Adenovirus occurs year-round with bumps as children get back to school in autumn. Yet in 2020, almost no parainfluenza, adenovirus, common coronaviruses, or human metapneumovirus were detected in either spring or autumn. This was supposed to be a banner summer-autumn for EV-D68 – but almost none was detected. Interestingly, the cockroach of viruses, rhinovirus, has its usual year (Figure 2).

What happened? Intense social mitigation interventions, including social distancing and closing daycares and schools, were likely major factors.4 For influenza, vaccine may have helped but uptake was not remarkably better than most prior years. There may have been “viral competition,”where a new or highly transmissible virus outcompetes less-transmissible viruses with lower affinity for respiratory receptors.5,6 Note that SARS-CoV-2 has very high affinity for the ACE2 receptor and has been highly prevalent. So, SARS-CoV-2 could fit the theoretical mold for a virus that outcompetes others.

Does it matter for the future? Blunted 2019-2020 and nearly absent 2020-2021 respiratory virus season may have set the stage for intense 2021-2022 rebounds for the non–SARS-CoV-2 viruses. We now have two whole and one partial birth cohort with no experience with seasonal respiratory viruses, including EV-D68 (and nonrespiratory viruses too – like norovirus, parechovirus, and other enteroviruses). Most viruses have particularly bad seasons every 2-3 years, thought to be caused by increasing accumulation of susceptible individuals in consecutive birth cohorts until a critical mass of susceptible individuals is achieved. The excess in susceptible individuals means that each contagious case is likely to expose one or more susceptible individuals, enhancing transmission and infection numbers in an ever-extending ripple effect. We have never had this many children aged under 3 years with no immunity to influenza, RSV, etc. So unless mother nature is kind (when has that happened lately?), expect rebound years for seasonal viruses as children return to daycare/schools and as social mitigation becomes less necessary in the waning pandemic.

Options? If you ramped up telehealth visits for the pandemic, that may be a saving grace, i.e., more efficiency so more “visits” can be completed per day, and less potential contact in reception rooms between well and ill children. And if there was ever a time to really intensify efforts to immunize all our pediatric patients, the next two seasons are just that. Adding a bit of a warning to families with young children also seems warranted. If they understand that, while 2021-2022 will be better for SARS-CoV-2, it is likely going to be worse for the other viruses.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Harrison CJ. 2020-2021 respiratory viral season: Onset, presentations, and testing likely to differ in pandemic, Pediatric News: September 17, 2020.

2. Olsen SJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1305-9.

3. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Surveillance. http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/respiratory-syncytial-virus/_documents/2021-w4-rsv-summary.pdf

4. Baker RE et al. PNAS. Dec 2020 117;(48):30547-53.

5. Sema Nickbakhsh et al. PNAS. Dec 2019 116;(52):27142-50.

6. Kirsten M et al. PNAS. Mar 2020 117;(13):6987.

In this column in September 2020, you read how common respiratory viruses’ seasons are usually so predictable, each virus arising, peaking, and then dying out in a predictable virus parade (Figure 1).1 Well, the predictable virus seasonal pattern was lost in 2020. Since March of 2020, it is striking how little activity was detected for the usual seasonal viruses in Kansas City after mid-March 2020 (Figure 2).2 So, my concern in September 2020 for possible rampant coinfections of common viruses with or in tandem with SARS-CoV-2 did not pan out. That said, the seasons for non–SARS-CoV-2 viruses did change; I just didn’t expect they would nearly disappear.

The 2020 winter-spring. In the first quarter (the last part of the overall 2019-2020 respiratory viral season), viral detections were chugging along as usual up to mid-March (Figure 2); influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and rhinovirus were the big players.

Influenza. In most years, influenza type B leads off and is quickly replaced by type A only to see B reemerge to end influenza season in March-April. In early 2020, both influenza type A and influenza type B cocirculated nearly equally, but both dropped like a rock in mid-March (Figure 2).2 Neither type has been seen since with the exception of sporadic detections – perhaps being false positives.

RSV. In the usual year in temperate mid-latitudes of the northern hemisphere, RSV season usually starts in early December, peaks in January-March, and declines gradually until the end of RSV season in April (Figure 1). In southern latitudes, RSV is less seasonal, being present most of the year, but peaking in “winter” months.3 But in 2020, RSV also disappeared in mid-March and has yet to reappear.

Other viruses. Small bumps in detection of parainfluenza of varying types usually frame influenza season, one B bump in early autumn and another in April-May. In most years, human metapneumovirus is detected on and off, with worse years at 2- to 3-year intervals. Adenovirus occurs year-round with bumps as children get back to school in autumn. Yet in 2020, almost no parainfluenza, adenovirus, common coronaviruses, or human metapneumovirus were detected in either spring or autumn. This was supposed to be a banner summer-autumn for EV-D68 – but almost none was detected. Interestingly, the cockroach of viruses, rhinovirus, has its usual year (Figure 2).

What happened? Intense social mitigation interventions, including social distancing and closing daycares and schools, were likely major factors.4 For influenza, vaccine may have helped but uptake was not remarkably better than most prior years. There may have been “viral competition,”where a new or highly transmissible virus outcompetes less-transmissible viruses with lower affinity for respiratory receptors.5,6 Note that SARS-CoV-2 has very high affinity for the ACE2 receptor and has been highly prevalent. So, SARS-CoV-2 could fit the theoretical mold for a virus that outcompetes others.

Does it matter for the future? Blunted 2019-2020 and nearly absent 2020-2021 respiratory virus season may have set the stage for intense 2021-2022 rebounds for the non–SARS-CoV-2 viruses. We now have two whole and one partial birth cohort with no experience with seasonal respiratory viruses, including EV-D68 (and nonrespiratory viruses too – like norovirus, parechovirus, and other enteroviruses). Most viruses have particularly bad seasons every 2-3 years, thought to be caused by increasing accumulation of susceptible individuals in consecutive birth cohorts until a critical mass of susceptible individuals is achieved. The excess in susceptible individuals means that each contagious case is likely to expose one or more susceptible individuals, enhancing transmission and infection numbers in an ever-extending ripple effect. We have never had this many children aged under 3 years with no immunity to influenza, RSV, etc. So unless mother nature is kind (when has that happened lately?), expect rebound years for seasonal viruses as children return to daycare/schools and as social mitigation becomes less necessary in the waning pandemic.

Options? If you ramped up telehealth visits for the pandemic, that may be a saving grace, i.e., more efficiency so more “visits” can be completed per day, and less potential contact in reception rooms between well and ill children. And if there was ever a time to really intensify efforts to immunize all our pediatric patients, the next two seasons are just that. Adding a bit of a warning to families with young children also seems warranted. If they understand that, while 2021-2022 will be better for SARS-CoV-2, it is likely going to be worse for the other viruses.

Dr. Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Mo. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Harrison CJ. 2020-2021 respiratory viral season: Onset, presentations, and testing likely to differ in pandemic, Pediatric News: September 17, 2020.

2. Olsen SJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1305-9.

3. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Surveillance. http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/respiratory-syncytial-virus/_documents/2021-w4-rsv-summary.pdf

4. Baker RE et al. PNAS. Dec 2020 117;(48):30547-53.

5. Sema Nickbakhsh et al. PNAS. Dec 2019 116;(52):27142-50.

6. Kirsten M et al. PNAS. Mar 2020 117;(13):6987.

Cumulative exposure to high-potency topical steroid doses drives osteoporosis fractures

In support of previously published case reports, in a dose-response relationship.

In a stepwise manner, the hazard ratios for major osteoporotic fracture (MOF) were found to start climbing incrementally for those with a cumulative topical steroid dose equivalent of more than 500 g of mometasone furoate when compared with exposure of 200-499 g, according to the team of investigators from the University of Copenhagen.

“Use of these drugs is very common, and we found an estimated population-attributable risk of as much as 4.3%,” the investigators reported in the study, published in JAMA Dermatology.

The retrospective cohort study drew data from the Danish National Patient Registry, which covers 99% of the country’s population. It was linked to the Danish National Prescription Registry, which captures data on pharmacy-dispensed medications. Data collected from the beginning of 2003 to the end of 2017 were evaluated.

Exposures to potent or very potent topical corticosteroids were converted into a single standard with potency equivalent to 1 mg/g of mometasone furoate. Four strata of exposure were compared to a reference exposure of 200-499 g. These were 500-999 g, 1,000-1,999 g, 2,000-9,999 g, and 10,000 g or greater.

For the first strata, the small increased risk for MOF did not reach significance (HR, 1.01; 95% confidence interval, 0.99-1.03), but each of the others did. These climbed from a 5% greater risk (HR 1.05 95% CI 1.02-1.08) for a cumulative exposure of 1,000 to 1,999 g, to a 10% greater risk (HR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.07-1.13) for a cumulative exposure of 2,000-9,999 g, and finally to a 27% greater risk (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.19-1.35) for a cumulative exposure of 10,000 g or higher.

The study included more than 700,000 individuals exposed to topical mometasone at a potency equivalent of 200 g or more over the study period. The reference group (200-499 g) was the largest (317,907 individuals). The first strata (500-999 g) included 186,359 patients; the second (1,000-1,999 g), 111,203 patients; the third (2,000-9,999 g), 94,334 patients; and the fifth (10,000 g or more), 13,448 patients.

“A 3% increase in the relative risk of osteoporosis and MOF was observed per doubling of the TCS dose,” according to the investigators.

Patients exposed to doses of high-potency topical steroids that put them at risk of MOF is limited but substantial, according to the senior author, Alexander Egeberg, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology and allergy at Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen.

“It is true that the risk is modest for the average user of topical steroids,” Dr. Egeberg said in an interview. However, despite the fact that topical steroids are intended for short-term use, “2% of all our users had been exposed to the equivalent of 10,000 g of mometasone, which mean 100 tubes of 100 g.”

If the other two strata at significantly increased risk of MOF (greater than 1,000 g) are included, an additional 28% of all users are facing the potential for clinically significant osteoporosis, according to the Danish data.

The adverse effect of steroids on bone metabolism has been established previously, and several studies have linked systemic corticosteroid exposure, including inhaled corticosteroids, with increased risk of osteoporotic fracture. For example, one study showed that patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on daily inhaled doses of the equivalent of fluticasone at or above 1,000 mcg for more than 4 years had about a 10% increased risk of MOF relative to those not exposed.

The data associate topical steroids with increased risk of osteoporotic fracture, but Dr. Egeberg said osteoporosis is not the only reason to use topical steroids prudently.

“It is important to keep in mind that osteoporosis and fractures are at the extreme end of the side-effect profile and that other side effects, such as striae formation, skin thinning, and dysregulated diabetes, can occur with much lower quantities of topical steroids,” Dr. Egeberg said

For avoiding this risk, “there are no specific cutoffs” recommended for topical steroids in current guidelines, but dermatologists should be aware that many of the indications for topical steroids, such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, involve skin with an impaired barrier function, exposing patients to an increased likelihood of absorption, according to Dr. Egeberg.

“A general rule of thumb that we use is that, if a patient with persistent disease activity requires a new prescription of the equivalent of 100 g mometasone every 1-2 months, it might be worth considering if there is a suitable alternative,” Dr. Egeberg said.

In an accompanying editorial, Rebecca D. Jackson, MD, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism in the department of internal medicine at Ohio State University, Columbus, agreed that no guidelines specific to avoiding the risks of topical corticosteroids are currently available, but she advised clinicians to be considering these risks nonetheless. In general, she suggested that topical steroids, like oral steroids, should be used at “the lowest dose for the shortest duration necessary to manage the underlying medical condition.”

The correlation between topical corticosteroids and increased risk of osteoporotic fracture, although not established previously in a large study, is not surprising, according to Victoria Werth, MD, chief of dermatology at the Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Hospital and professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.